Abstract

Background

Allergic rhinitis is the most common type of allergy worldwide. The accuracy of skin testing for allergic rhinitis is still debated. This health technology assessment had two objectives: to determine the diagnostic accuracy of skin-prick and intradermal testing in patients with suspected allergic rhinitis and to estimate the costs to the Ontario health system of skin testing for allergic rhinitis.

Methods

We searched All Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, CRD Health Technology Assessment Database, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and NHS Economic Evaluation Database for studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of skin-prick and intradermal testing for allergic rhinitis using nasal provocation as the reference standard. For the clinical evidence review, data extraction and quality assessment were performed using the QUADAS-2 tool. We used the bivariate random-effects model for meta-analysis. For the economic evidence review, we assessed studies using a modified checklist developed by the (United Kingdom) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. We estimated the annual cost of skin testing for allergic rhinitis in Ontario for 2015 to 2017 using provincial data on testing volumes and costs.

Results

We meta-analyzed seven studies with a total of 430 patients that assessed the accuracy of skin-prick testing. The pooled pair of sensitivity and specificity for skin-prick testing was 85% and 77%, respectively. We did not perform a meta-analysis for the diagnostic accuracy of intradermal testing due to the small number of studies (n = 4). Of these, two evaluated the accuracy of intradermal testing in confirming negative skin-prick testing results, with sensitivity ranging from 27% to 50% and specificity ranging from 60% to 100%. The other two studies evaluated the accuracy of intradermal testing as a stand-alone tool for diagnosing allergic rhinitis, with sensitivity ranging from 60% to 79% and specificity ranging from 68% to 69%. We estimated the budget impact of continuing to publicly fund skin testing for allergic rhinitis in Ontario to be between $2.5 million and $3.0 million per year.

Conclusions

Skin-prick testing is moderately accurate in identifying subjects with or without allergic rhinitis. The diagnostic accuracy of intradermal testing could not be well established from this review. Our best estimate is that publicly funding skin testing for allergic rhinitis costs the Ontario government approximately $2.5 million to $3.0 million per year.

BACKGROUND

Allergic rhinitis (also known as hay fever) is a collection of symptoms in the nose and eyes that develop when the immune system becomes sensitized and overreacts to airborne allergens. This condition is the most common allergic disorder worldwide (1) and among the leading chronic conditions affecting both children and adults. (2)

The diagnosis of allergic rhinitis is often made on the basis of clinical characteristics and response to pharmacotherapy. (3) Evidence that a patient has been sensitized to a known allergen usually involves a combination of skin or blood testing and the patient's exposure history. (4) Because skin-prick testing is easy to administer and less invasive, it is recommended for diagnosis of allergic rhinitis, followed by intradermal testing to confirm negative skin-prick test results. (5) There is no universally accepted “gold standard” test for detecting allergic rhinitis, although in many research studies, nasal provocation (applying the suspected allergen directly on the nasal mucosa) is used as the reference standard. Skin tests have a long history that can be traced back to the 1860s when Dr. Charles Blackley described a crude form of scratch test. (5) Skin-prick and intradermal tests were introduced in 1915 (6) and the 1920s, (7) respectively.

Despite the long history of skin tests for allergic rhinitis, uncertainty remains as to how accurate they are. The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care asked Health Quality Ontario to conduct a health technology assessment focused on skin testing for allergic rhinitis. Ideally, the assessment would have encompassed both the accuracy of skin testing and its incremental benefits on clinical outcomes. However, for the latter topic, our systematic search did not identify any relevant studies. Therefore, in this report we review the evidence from published studies that evaluated the accuracy of two types of skin tests for allergic rhinitis—skin-prick and intradermal testing.

A review on the effectiveness of allergen immunotherapy on clinical outcomes, recently done by the Ontario Drug Policy and Research Network at St. Michael's Hospital, sheds some light on the benefits of skin testing because testing is required for immunotherapy. That review suggests that allergen immunotherapy is more effective than placebo in reducing symptoms and medication score (a measure of how much a patient's medications provide relief from allergy symptoms) and in improving disease-specific quality of life. (8)

Objective of Analysis

The objective of this study was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of skin-prick and intradermal testing in children or adults with suspected symptoms of allergic rhinitis.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Description of Disease/Condition

Allergic rhinitis is characterized by epithelial accumulation of inflammatory cells in the nose, particularly mast cells, basophils and eosinophils. Upon interacting with immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies that have been in contact with allergens, these cells will release histamines and other inflammatory substances, resulting in one or more symptoms of allergic rhinitis. These symptoms include itchy and runny nose, sneezing and nasal congestion. (9)

Allergic rhinitis can be seasonal or perennial. The most common causes of seasonal allergic rhinitis include pollens from trees, grasses and weeds, as well as spores from fungi. Common causes of perennial allergic rhinitis include dust mites, cockroaches, animal dander, and fungi.

Symptoms of allergic rhinitis usually develop before age 20 years (10) and peak between age 20 and 40 years (the age of the most productive workforce), before gradually declining. (3) Allergic rhinitis contributes to unproductive time at work, difficulty sleeping, and less involvement in outdoor activities. (3, 11)

Prevalence and Incidence

Global Prevalence

The global prevalence of allergic rhinitis has increased considerably over the last 50 years (9) and is currently estimated to be between 10% and 30% for adults and as high as 40% for children. (1, 11)

Canadian Prevalence

The prevalence of allergic rhinitis in Canada is estimated to be between 20% and 25%. (12)

Canada Context

Allergy tests are covered under public health insurance in all provinces and territories. Appendix 1 provides details of this coverage for the jurisdictions that responded to our request for information.

Ontario Context

About two million tests for allergic rhinitis are funded annually through the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP). This represents approximately two-thirds of all allergy tests funded under OHIP. Most tests for allergic rhinitis are skin tests, and OHIP covers up to 50 tests of these tests per patient per year (a patient will often have numerous tests because each test is for a different allergen or group of related allergens).

Technology/Technique

Skin-prick testing is done by passing a sharp instrument such as a hypodermic needle, solid bore needle or blood lancet through a drop of allergen extract or a control solution on the patient's forearm or back. The skin is then gently lifted creating a small break in the epidermis, which allows the solution to penetrate. The peak reactivity of skin-prick testing is 15 to 20 minutes, at which time the wheal (hive) size is read in millimetres and compared with both a positive (usually a histamine solution) and a negative (usually a saline solution) control. Results are usually classified as positive if the wheal diameter at the site of contact is 3 mm greater than that of a negative control. (1)

Intradermal testing involves injecting a small amount of allergen between the epidermal and dermal layers of skin, using a disposable 0.5 to 1.0 millilitre syringe. The starting dose usually ranges from 100-fold to 1,000-fold dilutions of the concentrated extracts used for skin-prick testing. (1) Results for intradermal testing are read within 10 to 15 minutes using the same rules as those for skin-prick testing.

Factors influencing the reliability of both types of skin testing include skill of the tester, type of testing device, color of the skin, skin reactivity on the day of testing, potency of the allergen extract, and stability of test reagents. (1)

Regulatory Status

At least two skin-testing devices (e.g., Multi-Test II and ComforTen) and numerous allergen extracts have been approved by Health Canada.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE REVIEW

Research Questions

We had two research questions:

What is the diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity) of skin-prick testing in patients with suspected symptoms of allergic rhinitis?

What is the diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity) of intradermal testing in patients with suspected symptoms of allergic rhinitis?

Research Methods

Literature Search

We performed a literature search on April 25, 2015, using All Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, CRD Health Technology Assessment Database, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (Appendix 2 provides details of the search strategies). Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies reporting both sensitivity (rate of true-positives) and specificity (rate of true-negatives) or providing sufficient information to compute these two estimates

Studies using nasal provocation as the reference standard

Exclusion Criteria

Studies enrolling subjects with known allergic status (commonly referred to as “case-control” design in the diagnostic accuracy literature)

Studies using a reference standard other than nasal provocation

Outcomes of Interest

Sensitivity

Specificity

Statistical Analysis

We extracted estimates for sensitivity, specificity, and sample size from all eligible studies. We also computed sensitivity and/or specificity for studies that did not report these estimates but provided sufficient information for their derivation. We constructed forest plots to assess heterogeneity in test accuracy across studies. In case of substantial heterogeneity, we proceeded with a subgroup analysis to determine the reason for inconsistency. When the assumption of homogeneity was deemed appropriate, we pooled studies using the bivariate approach. (13) The pooled results were presented on a summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve, which included a 95% confidence ellipse. When the homogeneity assumption failed to hold, we presented sensitivity and specificity separately for each study. The logit transformation was used for the calculation of study-specific confidence intervals to account for asymmetry in the distribution of sensitivity and specificity. When estimates were on or too close to the boundary of the parameter space (i.e., values for sensitivity or specificity were equal or approximately equal to 0% or 100%), a continuity correction factor of 1% was applied. All analyses were performed using the MADA software package in R version 3.0.2.

Quality of Evidence

The risk of bias and applicability concerns for each bivariate outcome within studies was examined according to the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) criteria. (14) This tool consists of four key domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. The overall quality of the body of evidence was examined using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria. (15) This tool consists of three key domains: study design, limitations (risk of bias), and indirectness.

Results of Evidence Review

Screening Process

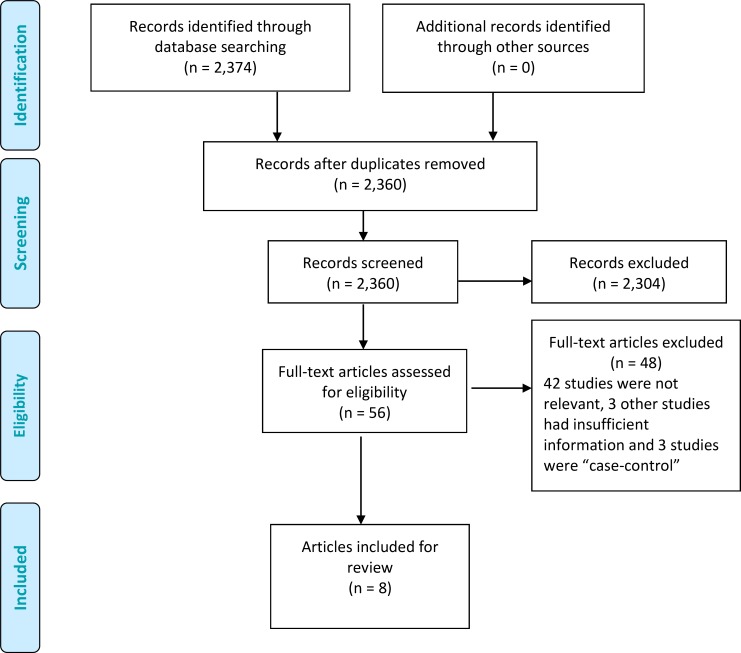

The database search yielded 2,360 citations published up to April 25, 2015. In the initial screening we excluded articles based on information in the title and abstract. We found 2,304 articles to be irrelevant. After full-text screening, we further excluded 48 articles, leaving eight articles included in this review. Figure 1 summarizes the selection process for a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) analysis.

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al. (25)

All eight articles assessed the accuracy of skin-prick testing. Of these, four also examined the accuracy of intradermal testing. In the meta-analysis of skin-prick testing, we excluded one of the two studies by Krouse et al (16) as it was restricted to alternaria, a fungus allergen that was not assessed by any other study, and the findings deviated substantially from the rest. We present results for Krouse et al (16) first separately and then as part of the sensitivity analysis, as we describe in subsequent sections. The final number of eligible studies was 12 (a single article could report on multiple studies).

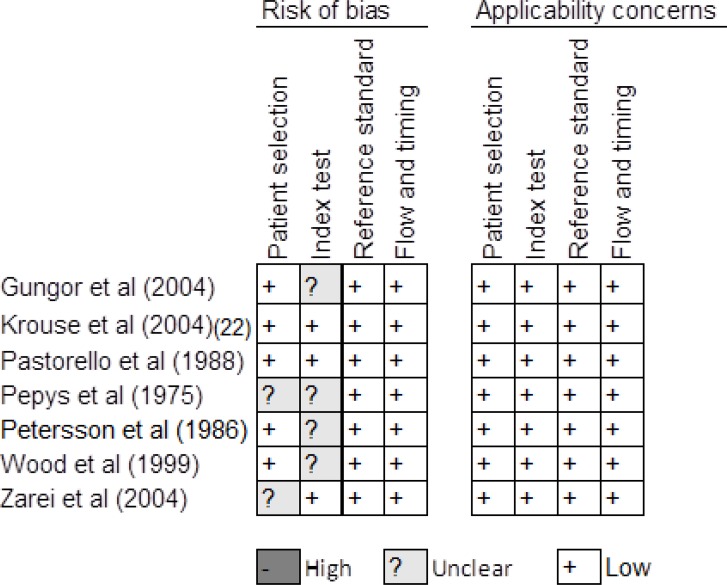

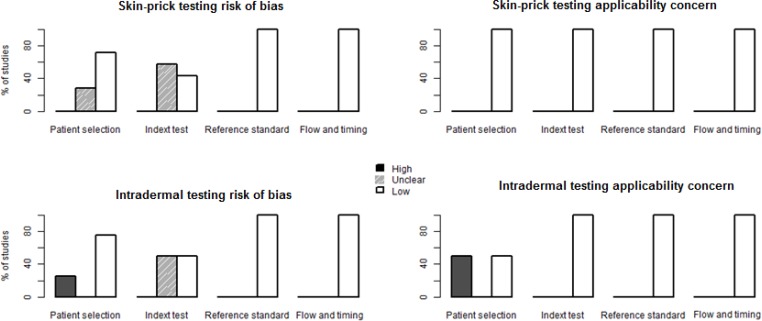

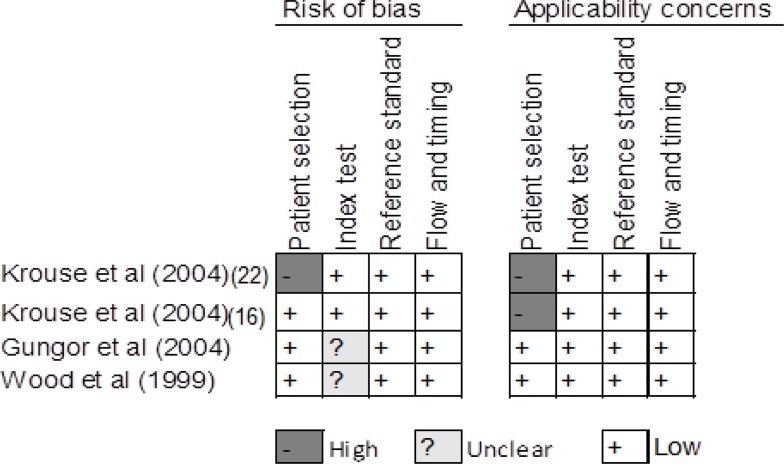

Methodological Quality of Evidence

We summarize assessment of risk of bias and applicability concerns in Figures 2 to 4. For skin-prick testing, the risk of bias was unclear in five studies. (17–21) For intradermal testing, the risk of bias was high in one study (16) and unknown in two studies. (17, 21) Applicability concerns were high in two studies. (16, 22)

Figure 2: Risk of Bias in Studies of Skin-Prick Testing.

Reviewer's judgment about the risk of bias and applicability concerns in each included study that assessed the accuracy of skin-prick testing. See Whiting et al (14) for a detailed explanation of domains in the QUADAS-2 assessment tool.

Studies reviewed: Gungor et al, (17) Krouse et al, (22) Pastorello et al, (24) Pepys et al, (18) Petersson et al, (19) Wood et al, (20) Zarei et al. (21)

Figure 4: Methodological Quality of the Included Studies.

See Whiting et al (14) for a detailed explanation of domains for risk of bias and applicability concern.

Figure 3: Risk of Bias in Studies of Intradermal Testing.

Reviewer's judgment about the risk of bias and applicability concerns in each included study that assessed the accuracy of intradermal testing. See Whiting et al (14) for a detailed explanation of domains in the QUADAS-2 assessment tool.

Studies reviewed: Krouse et al, (16) Krouse et al, (22) Gungor et al, (17) Wood et al. (20)

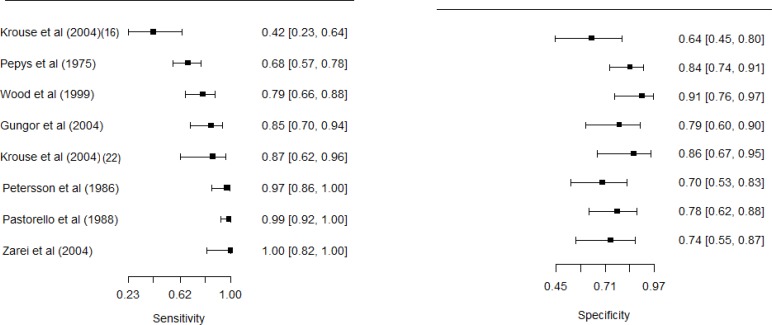

Figure 5 shows how we evaluated the potential for heterogeneity in estimates for the accuracy of skin-prick testing. The inclusion of Krouse et al (16) introduced a discernible heterogeneity. Specifically, the 95% confidence interval (CI) for sensitivity barely overlapped with the CIs of other studies, and the inclusion of this study swayed the correlation between sensitivity and specificity toward a positive value. This violates a requirement for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies: the correlation between sensitivity and specificity must not be positive for the homogeneity assumption to be valid. When this study was removed from the analysis, the negative correlation was detected (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Forest Plots for Studies Evaluating the Accuracy of Skin-Prick Tests.

Estimates from Krouse et al (16) deviate considerably from the rest: its inclusion attenuates the negative correlation between sensitivity and specificity.

Data sources: Krouse et al, (16) Pepys et al, (18) Wood et al, (20) Gungor et al, (17) Krouse et al, (22) Petersson et al, (19) Pastorello et al, (24) Zarei et al (21).

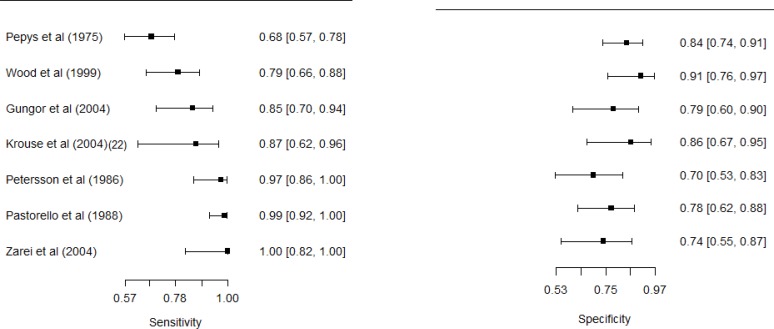

Figure 6: Forest Plots for Studies Evaluating the Accuracy of Skin-Prick Tests, Excluding Krouse et al (16).

Data sources: Pepys et al, (18) Wood et al, (20) Gungor et al, (17) Krouse et al, (22) Petersson et al, (19) Pastorello et al, (24) Zarei et al. (21)

Five studies either did not report a cut-off value for the wheal size (17) or used a 3 mm diameter as the minimum wheal size to classify a test result as positive, (17–20) as recommended by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI). (5) Given the relation between the cut-off value and sensitivity and specificity, and because a 3-mm cut-off value might not be optimal in all settings, (23) we classified these studies as having an unclear risk of bias. Moreover, the sample size for two studies evaluating the accuracy of intradermal testing was small, calling into question whether findings from these studies apply to the majority of suspected allergic rhinitis patients presented in clinics. (16, 22) We classified both studies as having high applicability concern.

Overall, the quality of evidence on the diagnostic accuracy of skin-prick testing was moderate, downgraded on limitations and inconsistency (a subdomain within indirect evidence). The quality of evidence on the diagnostic accuracy of intradermal testing was very low, downgraded on limitations, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Skin-Prick Testing

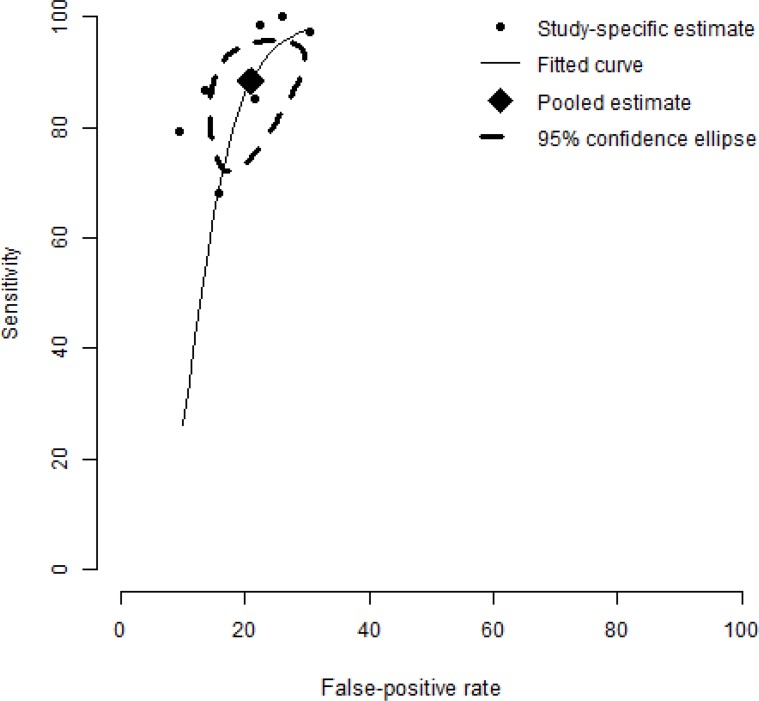

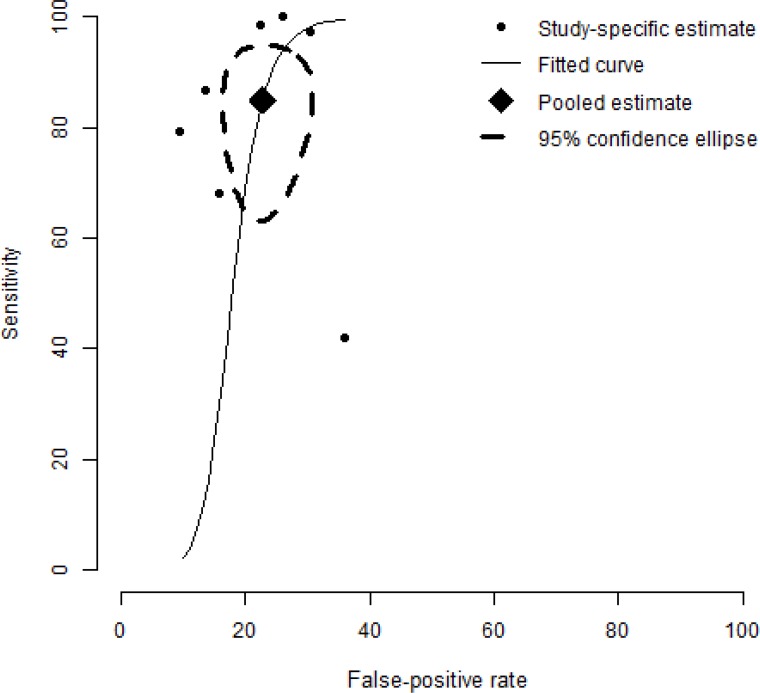

A meta-analysis of skin-prick testing yielded a pooled estimate of sensitivity and specificity of 88.4% and 77.1%, respectively (Figure 7). A sensitivity analysis incorporating the study of Krouse et al (16) did not alter the conclusion, with sensitivity and specificity fluctuating only slightly, to 85.0% and 77.3%, respectively (Figure 8). See Figure 5 for estimates of sensitivity and specificity in Krouse et al. (16)

Figure 7: Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic (SROC) Curve of Seven Studies Evaluating the Accuracy of Skin-Testing for Allergic Rhinitis.

The SROC curve is plotted using a bivariate normal distribution model. The estimate of the pooled pair of sensitivity and specificity is 88.4% and 77.1%.

Figure 8: Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic (SROC) Curve Showing the Sensitivity of Results for the Accuracy of Skin Testing for Allergic Rhinitis, Including Krouse et al (16).

Compared to Figure 7, the estimate of the pooled pair of sensitivity and specificity fluctuates slightly, to 85.0% and 77.3%.

Intradermal Testing

When intradermal testing was used to confirm negative skin-prick testing results, the estimates for sensitivity ranged from 27% (95% CI 10%–57%) to 50% (sample size was too small for estimation of CI using asymptotic-based statistical tests). Estimates for specificity ranged from 69% (95% CI 51%–83%) to 100% (83%–100%). (16, 22)

When intradermal testing was evaluated as a stand-alone tool for diagnosing allergic rhinitis, the estimate for sensitivity was between 60% (95% CI 31%–83%) and 79% (63%–90%), and the estimate for specificity was between 68% (95% CI 49%–82%) and 69% (52%–86%). (17, 20)

Single-Allergen Versus Multiple-Allergen Studies

Because testing for multiple allergens might increase the probability of identifying an allergen causing clinical symptoms (compared with testing for a single allergen), we present results for single- and multiple-allergen studies separately, below. The most frequently reported allergen extracts were timothy grass (reported by four studies) (18, 19, 22) and cat (reported by three studies). (20, 21)

Four studies that evaluated the accuracy of skin-prick testing (17, 20–22) restricted the analysis to single-allergen extracts. Sensitivity ranged from 79% (95% CI 66%–88%) to 100% (82%–100%) and specificity from 79% (95% CI 66%–88%) to 91% (76%–97%), when Krouse et al (16) was excluded. When we included Krouse et al, (16) the lowest values for sensitivity and specificity were reduced to 42% (95% CI 23%–64%) and 64% (45%–80%), respectively.

All studies (16, 17, 20, 22) that evaluated the accuracy of intradermal testing used single-allergen extracts. These results are reported above, under “Intradermal Testing.”

Three studies examined multiple-allergen extracts and all focused on the accuracy of skin-prick testing. (18, 19, 24) The reported sensitivity ranged from 68% (95% CI 57%–78%) to 97% (86%–100%), and specificity ranged from 70% (95% CI 54%–86%) to 84% (74%–91%).

Studies Applying the Recommended Cut-Off Value

Only four studies (16, 20–22) applied the 3-mm cut-off value recommended by AAAAI/ACAAI for classifying positive test results. (5) Sensitivity and specificity reported in the studies of skin-prick testing ranged from 42% (95% CI 23%–64%) to 100% (82%–100%) and 64% (95% CI 45%–80%) to 86% (67%–95%), respectively. For intradermal testing, sensitivity ranged from 27% (95% CI 10%–57%) to 50% (sample size was too small for estimation of CI), and specificity from 69% (95% CI 44%–86%) to 100% (83%–100%).

Studies Applying Other Cut-Off Values

Seven studies (17–20) applied cut-off values that differed from the AAAAI/ACAAI recommendation. The reported sensitivity for skin-prick testing was between 79% (95% CI 66%–88%) and 97% (86%–100%), and specificity was between 79% (95% CI 60%–90%) and 91% (76%–97%). For intradermal testing, sensitivity was between 60% (95% CI 31%–83%) and 79% (63%–90%), and specificity was between 68% (49%–82%) and 69% (52%–86%).

Table 1 provides a summary of these findings, and Table 2 lists the included studies and their diagnostic accuracy findings.

Table 1:

Summary of Main Findings

| Population: adults and children with suspected symptoms of allergic rhinitis |

| Index test: skin-prick or intradermal |

| Target condition: allergic rhinitis |

| Reference standard: nasal provocation |

| Studies included: 12 (3 used multiple-allergen extracts and 9 used single-allergen extracts) |

| Type of Diagnostic Test | Year of Publication | Included Studies, N | Included Individuals, N | Age Range, Years | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin-pricka | 1975–2004 | 7 | 430 | ≥ 9 | 88.4 | 77.1 |

| Intradermal as a confirmatory test | 2004 | 2 | 48 | ≥ 18 | 27 to 50 | 69 to 100 |

| Intradermal as a stand-alone test | 1999–2004 | 2 | 101 | ≥ 18 | 60 to 79 | 68 to 69 |

Table 2:

Included Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy of Skin Testing for Allergic Rhinitis

| Author, Year | Age Range, Years | Index Testa | Wheal Size Cut-Off | True Positive, n | True Negative, n | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Allergen Extracts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pepys et al, 1975 (18) | Not provided | Skin prick | ≥ 1 mm | 72 | 64 | 68.1 | 84.4 | Sweet vernal, cocksfoot, meadow fescue, rye, timothy, meadow grass |

| Petersson et al, 1986 (19) | 14–53 | Skin prick | ≥ 0.5 mm larger than a positive control | 36 | 33 | 97.0 | 70.0 | Birch and timothy grass |

| Pastorello et al, 1988 (24) | 9–57 | Skin prick | ≥ 3 mm and >100,000 BU/ml | 70 | 31 | 98.0 | 70.0 | Grass, mugwort, birch, pellitory, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (house dust mite) |

| Wood et al, 1999 (20) | 18–65 | Skin prick | ≥ 3 mm larger than a negative control plus 1.5 mm larger than a positive control | 48 | 32 | 79.0 | 91.0 | Cat |

| Wood et al, 1999 (20) | 18–65 | Intradermal | ≥ 6 mm | 10 | 29 | 60.0 | 68.9 | Cat |

| Zarei et al, 2004 (21) | 25–66 | Skin prick | ≥ 3 mm larger than a negative control | 18 | 27 | 100.0 | 74.1 | Cat |

| Krouse et al, 2004 (22) | 18–70 | Skin prick | ≥ 3 mm larger than a negative control | 15 | 22 | 87.0 | 86.0 | Timothy grass |

| Krouse et al, 2004 (22) | 18–70 | Intradermal | ≥ 3 mm larger than a negative control | 2 | 19 | 50.0 | 100.0 | Timothy grass |

| Krouse et al, 2004 (16) | 18–70 | Skin prick | ≥ 3 mm larger than a negative control | 19 | 25 | 42.0 | 64.0 | Alternaria |

| Krouse et al, 2004 (16) | 18–70 | Intradermal | ≥ 3 mm larger than a negative control | 11 | 16 | 27.0 | 69.0 | Alternaria |

| Gungor et al, 2004 (17) | ≥ 18 | Skin prick | Not clear | 34 | 28 | 85.3 | 78.6 | Ragweed |

| Gungor et al, 2004 (17) | ≥ 18 | Intradermal | First wheal: ≥ 2 mm larger than a negative control; second wheal: ≥ 2 mm larger than the preceding one | 34 | 28 | 79.4 | 67.9 | Ragweed |

All studies used nasal provocation as the reference standard.

Conclusions

Based on moderate quality evidence, we found that skin-prick testing is reasonably accurate in identifying patients with suspected symptoms of allergic rhinitis.

Because of the small number of studies and small sample size within studies, we were unable to determine the degree of accuracy of intradermal testing.

Given that children less than nine years old were not represented in the studies included in this review, our findings should not be extrapolated to this group of patients.

ECONOMIC EVIDENCE REVIEW

Objective

The objective of this analysis was to review the literature on the cost-effectiveness of skin testing for allergic rhinitis.

Methods

Sources

We performed an economic literature search on May 8, 2015, using All Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and Health Technology Assessment, for studies published to May 8, 2015. We also extracted economic evaluation reports developed by health technology assessment agencies by searching the websites of the following organizations: the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, the Institute of Health Economics, the Institut national d'excellence en santé et en services sociaux, the Technology Assessment Unit of the McGill University Health Centre, and the Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry (available at; https://research.tufts-nemc.org/cear4/). Finally, we reviewed the reference lists of the included economic literature for any additional relevant studies not identified in the systematic search.

Search Strategy

We based our search terms on those used in the clinical evidence review in this report and applied economic filters developed by the medical librarians at Health Quality Ontario. Appendix 2 provides details of the search strategies.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published up to May 8, 2015

Studies in patients receiving skin-prick or intradermal allergy tests

Studies in patients with allergic rhinitis

Exclusion Criteria

Abstracts, commentary, editorials, conference proceedings

Outcomes of Interest

Cost per quality-adjusted life-year, cost per allergy avoided

Literature Screening

A single reviewer reviewed titles and abstracts. For those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, we obtained full-text articles.

Applicability Assessment and Methodological Appraisal

We determined the usefulness of each identified study by applying a modified methodology checklist for economic evaluations developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom (NICE). The original checklist is used to inform development of clinical guidelines by NICE. (26) We modified the wording of the questions to remove references to guidelines and make the checklist Ontario-specific.

This checklist is separated into two sections. The first section is used to assess the applicability of the study to the research question. If the study is directly or partially applicable to the research question, the second half of the checklist is used to assess the quality of the study and determine whether it has minor limitations, potentially serious limitations, or very serious limitations.

Limitations

The economic literature review was conducted by a single reviewer.

Results

Literature Search

The database search yielded 433 citations published up to May 8, 2015 (with duplicates removed). Articles were excluded based on information in the title and abstract. Figure 9 presents the flow diagram for a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) analysis.

Figure 9: PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.

Critical Review

We identified and critically reviewed one study by Lewis and colleagues. (27) This study was judged to be not applicable to the research question because the primary clinical outcome (number of allergy patients identified) used in this study was not considered appropriate to answer our study question (Appendix 4).

Discussion and Conclusions

From our review of the economic literature, we did not find any economic evaluations of skin testing for allergy. We are therefore unable to provide an estimate of cost-effectiveness of skin testing for allergic rhinitis based on the literature. Given the lack of economic evaluations on skin testing for allergy and limited information on the impact of skin testing on clinical outcomes and downstream effects, an economic evaluation was not conducted to determine the cost-effectiveness of skin testing for allergic rhinitis.

BUDGET IMPACT ANALYSIS

We conducted a budget impact analysis from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care to determine the estimated cost burden of skin testing for allergic rhinitis over three years (2015 to 2017). All costs are reported in 2015 Canadian dollars.

Objective

The objective of this analysis was to determine the budget impact of continued funding of skin testing for allergic rhinitis.

Methods

Scenarios

We modelled four scenarios.

In the primary scenario (1a), we evaluated the total cost of skin testing for patients diagnosed with allergic rhinitis. This scenario includes only the cost of the testing itself, with the assumption that, in the absence of skin testing, patients will still be seen by their physician to discuss various treatment options.

In the secondary scenario (2a), we evaluated the same cost as in scenario 1a and included the cost of the physician consultation where the skin test occurred. This scenario assumes that skin testing was the main reason for the consultation and that the visit would not occur if skin testing was not available.

In scenarios 1b and 2b, we recalculated the primary and secondary scenarios excluding skin tests administered for immunotherapy (“allergy shots,” by injection or orally). These scenarios were conducted because allergy testing is required for immunotherapy (clinical expert, written communication, May 2015). In scenarios 1b and 2b, the total cost of skin testing was calculated for a maximum number of tests billable per year per patient of 60 and 20. These maximums were based on the largest and smallest number of billable tests allowed according to provincial physician fee schedules across Canada. (28, 29)

Target Population

All Skin Testing for Allergic Rhinitis

To determine the number of patients receiving skin tests, we used administrative data from the Ontario IntelliHEALTH data system for the years 2009 to 2013. All patients receiving allergy skin tests were identified through billing data from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP). The identified cohorts were then further restricted to patients who also had a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis (ICD-9-CM code 477) when the skin test was administered. The Ontario physician schedule of benefits procedure codes used to identify skin-testing volumes are G209 (technical component of skin testing, to a maximum of 50 per patient per year) and G197 (professional component of skin testing, to a maximum of 50 per patient per year). (30) The technical component of skin testing includes preparing and performing the procedure, arranging for follow-up care, producing records for physician interpretation and providing the appropriate supplies, equipment and premises for the testing. The professional component includes clinical supervision, post-procedure monitoring and interpreting procedure results. (30)

Table 3 shows the number of Ontario patients who received the technical and/or professional components of skin tests for allergic rhinitis and the total volume of tests ordered each year from 2009 to 2013. From these numbers, the mean number of individual tests ordered per visit is approximately 36. Physicians are allowed to administer as many allergy skin tests per visit as they want. However, OHIP limits reimbursement to 50 tests per patient per year. Thus, all billings greater than this limit were converted to 50 tests for our analysis. Table 3 also shows that skin testing for allergic rhinitis accounted for about 28% to 34% of all allergy skin testing in Ontario over this five-year period.

Table 3:

Annual Number of Patients, Visits and Tests Ordered for Skin Testing for Allergic Rhinitis

| Year | Skin Testing – Technical Component Totals | Skin Testing – Professional Component Totals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | Visits, N | Tests for Allergic Rhinitis, N | All Allergy Skin Tests, N (% for Allergic Rhinitis) | Patients, N | Visits, N | Tests for Allergic Rhinitis, N | All Allergy Skin Tests, N (% for Allergic Rhinitis) | |

| 2013 | 60,651 | 61,688 | 2,244,050 | 6,519,616 (34.4) | 61,835 | 60,870 | 2,255,025 | 6,518,905 (34.6) |

| 2012 | 54,532 | 55,533 | 2,001,230 | 6,289,648 (31.8) | 55,636 | 54,664 | 2,005,015 | 6,318,306 (31.7) |

| 2011 | 54,432 | 55,431 | 2,034,211 | 6,599,665 (30.8) | 55,530 | 54,529 | 2,036,825 | 6,593,319 (30.9) |

| 2010 | 51,480 | 52,487 | 1,961,802 | 6,451,951 (30.4) | 52,541 | 51,526 | 1,963,548 | 6,445,850 (30.5) |

| 2009 | 47,358 | 48,279 | 1,823,880 | 6,414,255 (28.5) | 48,226 | 47,307 | 1,822,516 | 6,395,840 (28.5) |

Data source: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, IntelliHEALTH ONTARIO.

The total number of patients identified through the professional fee code is larger than the technical fee code for each year. Therefore, we used the numbers associated with the professional fee code to extrapolate for future years.

We estimated the number of patients and physician visits and the total volume of skin tests for allergic rhinitis in Ontario in 2015 to 2017, using projections based on numbers from past years (Table 4).

Table 4:

Estimated Number of Patients, Physician Visits and Skin Tests for Allergic Rhinitis, 2015 to 2017

| Intervention | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients receiving skin tests | 73,282 | 79,488 | 85,694 |

| Total number of physician visits with skin testing | 74,233 | 80,432 | 86,631 |

| Total volume of skin tests ordered | 2,755,045 | 3,005,055 | 3,255,065 |

Skin Testing for Immunotherapy

To calculate the proportion of patients receiving allergy skin tests who will proceed to immunotherapy, the entire cohort of individuals who received skin testing for allergic rhinitis in 2011 was followed forward using administrative data until the end of fiscal year 2011/12 to determine if they received immunotherapy. The specific procedure codes used to identify immunotherapy are G202 (hyposensitization – each injection) and G212 (hyposensitization – when sole reason for visit, including first injection). (30)

The number of patients who received skin tests for allergic rhinitis and then proceeded to immunotherapy in 2011/2012 is 4,102. This represents 7.5% of the cohort of all patients receiving skin tests for allergic rhinitis, a proportion in line with the experience of an allergist we consulted (clinical expert, written communication, May 2015). Assuming that patients receive only one round of skin tests for immunotherapy, the total number of patients receiving skin tests for allergic rhinitis each year was multiplied by 7.5% to get the total number of visits each year for immunotherapy-related allergy skin testing. This number was then multiplied by the mean number of tests ordered per visit to get the volume of allergy skin tests that would be related to immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Finally, this number was subtracted from the total number of all skin tests for allergic rhinitis to get the annual volume of tests excluding tests for immunotherapy (Table 5).

Table 5:

Estimated Number of Patients, Physician Visits and Skin Tests for Allergic Rhinitis, 2015 To 2017, Excluding Tests for Immunotherapy

| Intervention | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of physician visits with skin testing | 74,233 | 80,432 | 86,631 |

| Total number of visits for immunotherapy-related skin testing (7.5% of total number of physician visits) | 5,567 | 6,032 | 6,497 |

| Total volume of immunotherapy-related skin tests (number of immunotherapy-related visits with skin testing multiplied by 36 tests per visit) | 200,412 | 217,152 | 233,892 |

| Total volume of skin tests ordered | 2,755,045 | 3,005,055 | 3,255,065 |

| Total volume of skin tests excluding immunotherapy-related skin tests | 2,554,633 | 2,787,903 | 3,021,173 |

Resources and Costs

Cost of Administering Allergy Skin Tests

In scenario 1a, the cost of skin testing for allergic rhinitis includes only the cost of the test as billed by the physician. In scenario 2a, the cost of skin testing also includes the cost of the physician visit. The tests are commonly administered by an allergist (internal medicine specialist), general practitioner, paediatrician, or respirologist. For scenario 2a, the weighted average physician cost was calculated by measuring the proportion of physicians from each speciality who administered allergy skin tests during the years 2011 to 2013. All unit costs were derived from the Ontario schedule of benefits for physician services. (30) Unit costs and the proportion of physicians from each speciality administering allergy skin tests are presented in Table 6. The weighted cost for physician visits is estimated to be $153.

Table 6:

Unit Costs of Allergy Skin Testing and Proportion of Testing by Specialty

| Variable | Cost | Number of Times Skin Tests Ordered (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Skin testing – technical component (G209) | $0.69 | |

| Skin testing – professional component (G197) | $0.19 | |

| Internal medicine – consultation (A135) | $157.00 | 71,310 (41) |

| Paediatrics – consultation (A265) | $167.00 | 71,294 (41) |

| General practitioner – consultation (A005) | $77.20 | 16,987 (10) |

| Clinical immunology – consultation (A625) | $157.00 | 12,208 (7) |

| Respiratory disease – consultation (A475) | $157.00 | 922 (<1) |

| Laboratory medicine - consultation | $102.00 | 150 (<1) |

| Otolaryngology – consultation (A245) | $77.90 | 126 (<1) |

Data sources: Ontario Schedule of Benefits for Physician Services; (30) Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, IntelliHEALTH ONTARIO.

Number of Allergy Skin Tests Administered per Physician Visit

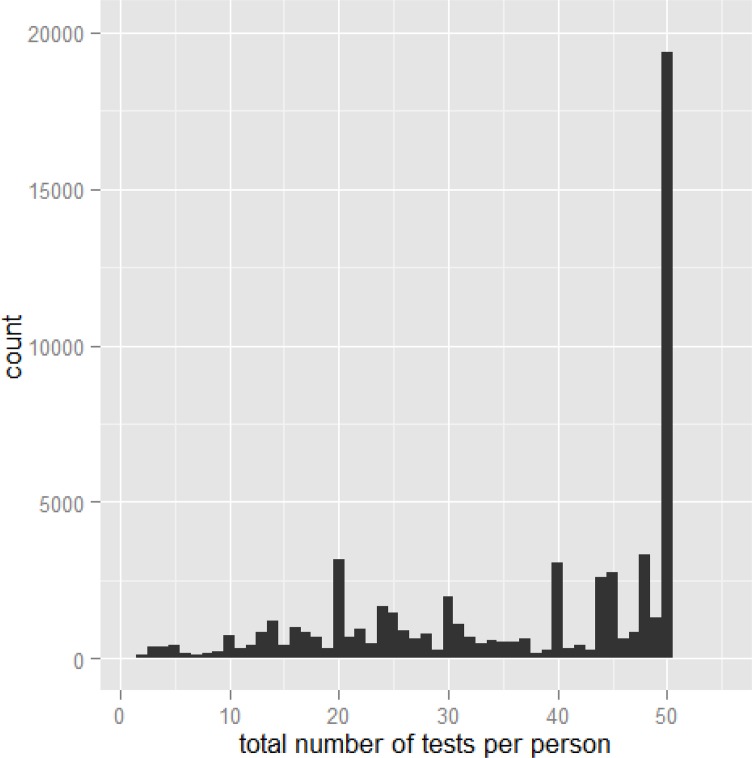

As shown in Figure 10, the distribution of the number of skin tests administered per physician visit appears to be weighted heavily to the right. As a result, we measured the median number of skin tests administered per physician visit (43 in 2013; interquartile range 24–50).

Figure 10: Distribution of the Number of Skin Allergy Tests Ordered per Person per Physician Visit in 2013.

Data source: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, IntelliHEALTH ONTARIO.

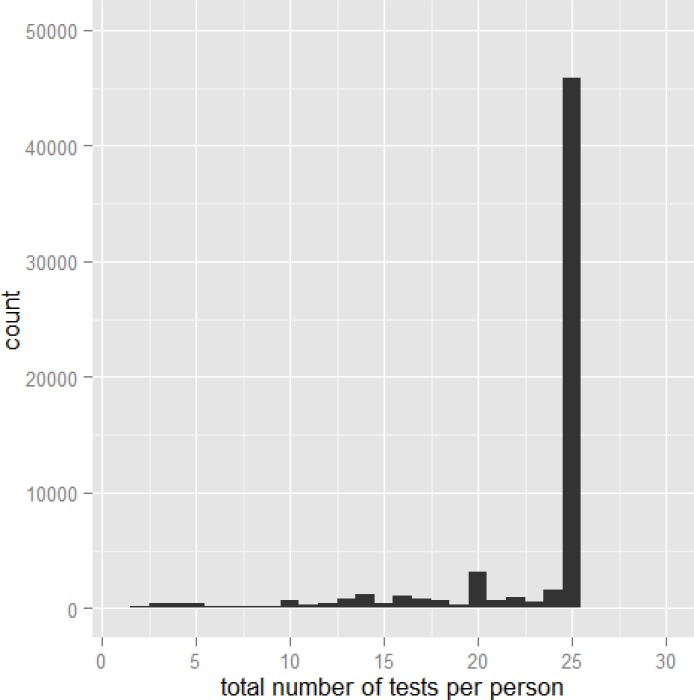

Volume of Allergy Skin Tests at Different Thresholds

To calculate the number of skin tests for allergic rhinitis that would be reimbursed if the threshold was lowered, all volume data between 2009 and 2013 were recalculated with all orders above the new number lowered to the new threshold. For example, with a new maximum of 25 tests per patient per year, the distribution of the total number of tests ordered per physician visit is presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11: Distribution of the Number of Allergy Skin Tests Billable per Physician Visit in 2013 if the Maximum Number of Tests per Patient per Year was Limited to 25.

Data source: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, IntelliHEALTH ONTARIO.

The estimated volume of skin tests for allergic rhinitis that would be ordered between 2015 and 2017 at various maximum thresholds is presented in Table 7.

Table 7:

Estimated Number of Skin Tests for Allergic Rhinitis Ordered at Various Maximum Thresholds, 2015 to 2017

| Total Volume of Skin Tests Ordered | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Number of Tests per Patient per Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| 50 (current threshold) | 2,755,045 | 3,005,055 | 3,255,065 |

| 20 | 1,422,543 | 1,551,607 | 1,680,671 |

| 60 | 2,755,997 | 3,006,234 | 3,256,471 |

Analysis

We determined the budget impact of skin testing for allergic rhinitis by multiplying the cost per test by the extrapolated volume of skin tests per year. To exclude skin testing connected to immunotherapy, the total volume of testing was reduced by 7.5%.

Results

Table 8 presents the budget impact of skin testing for allergic rhinitis under different scenarios.

Table 8:

Budget Impact of Skin Testing for Allergic Rhinitis in Ontario

| Scenario | 2015, $ million | 2016, $ million | 2017, $ million |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a (primary scenario) – for cost of test | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.9 |

| 1b – for cost of test excluding patients proceeding to immunotherapy | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| 2a (secondary scenario) – for cost of test and physician visit | 13.8 | 15.0 | 16.1 |

| 2b – for cost of test and physician visit less patients proceeding to immunotherapy | 12.8 | 13.8 | 14.9 |

| 1a with a maximum of 20 tests per patient per year | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| 1a with a maximum of 60 tests per patient per year | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

Limitations

Our analysis has several limitations. First, the cohort of patients receiving skin tests for allergic rhinitis was identified by physician billing claims. We included claims for skin testing for individuals diagnosed with allergic rhinitis. This should have captured most cases. However, there is a sizable cohort of individuals who received allergy skin tests but did not have a diagnosis entered. Some of these people may have allergic rhinitis; thus, our analysis may be an underestimate. Second, the number of individuals receiving an allergy skin test followed by immunotherapy was limited to cases where an immunotherapy claim was made within the same or following fiscal year. The appropriate duration between allergy test and immunotherapy is unknown. Therefore, our criteria may overestimate or underestimate the number of individuals proceeding to immunotherapy. Finally, there is no literature on the downstream costs associated with allergy skin testing. As a result, our budget impact analysis was restricted to the cost of the test and the physician costs.

Discussion and Conclusions

From the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, our best estimate of the cost of continued funding of skin testing for allergic rhinitis is $2.4 million to $2.9 million per year. If tests associated with immunotherapy are excluded, the annual cost is slightly lower, between $2.2 million and $2.7 million. Adding the cost of the physician visit increases the cost of skin testing for allergic rhinitis to as high as $13.8 million to $16.1 million per year ($12.8 million to $14.9 million if immunotherapy is excluded).

Acknowledgments

The medical editor was Amy Zierler. Others involved in the development and production of this report were Irfan Dhalla, Nancy Sikich, Andree Mitchell, Merissa Mohamed, Claude Soulodre, and Jessica Verhey.

We are grateful to the following experts for their technical advice:

| Ms. Sandra Knowles | Drug Policy Research Specialist | Ontario Drug Policy Research Network |

| Dr. Karen Binkley | Associate Professor | Department of Medicine, University of Toronto |

| Allergist/Immunologist | St. Michael's Hospital | |

| Dr. Paul Keith | Associate Professor | Department of Medicine, McMaster University |

| Allergist/Immunologist | Hamilton Health Sciences | |

| Dr. Holly Knowles | Family Physician | St. Michael's Hospital |

| Dr. Gordon Guyatt | Distinguished Professor | Department of Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics, McMaster University |

Glossary

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AAAAI

American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

- ACAAI

American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- OHIP

Ontario Health Insurance Plan

- QUADAS

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Provincial/Territorial Insurance Coverage of Allergy Testing

| Province/Territory | Coverage of Allergy Testinga |

|---|---|

| Alberta | The Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan provides coverage for an office visit where a physician provides allergy skin tests, but not the serum (allergen) used. As such, the patient is responsible for the cost of the serums. |

| British Colombia | Allergy skin test fees are payable to specialists qualified by the Royal College Certification in Clinical Immunology and Allergy, or equivalent as approved by the BC Society of Allergy and Immunology, in addition to consultations. The approved indications for allergen-specific antibodies are history of life-threatening allergic reactions or presence of generalized skin disease. |

| Manitoba | Allergy services, including allergy testing, are insured services in Manitoba and are covered by the provincial health insurance plan. |

| Northwest Territories | Testing for allergies may be funded but have to be approved as they are done out of the territory, in Edmonton, Alberta. |

| Ontario | Skin tests are covered under the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. Blood tests are covered by laboratory charges or hospital budget depending on where the test is performed. |

| Prince Edward Island | The insurance plan covers the skin tests and counselling. Patients may be required to pay $35 for serum. |

| Québec | Allergy tests are covered under the Québec Health Insurance Plan when they are performed by physicians participating in the plan. In private clinics or offices, however, physicians are allowed to bill patients for the cost of medications and anesthetic agents used as part of insured services. The solutions (allergen extracts) needed for the tests are considered medications, which means that patients could be billed for these solutions, and, in this case, the plan will not reimburse them. |

| Saskatchewan | Allergy testing provided by physicians is covered by the provincial health insurance plan. |

| Yukon | Consults and allergy testing are insured services with Yukon Health. Material fees are not insured and are the patient's responsibility. |

From provincial/territorial medical consultants who responded to our requests for information.

Appendix 2: Literature Search Strategies

Clinical Evidence Review

Database: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials <March 2015>, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews <2005 to March 2015>, EBM Reviews - Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects <1st Quarter 2015>, EBM Reviews - Health Technology Assessment <1st Quarter 2015>, EBM Reviews - NHS Economic Evaluation Database <1st Quarter 2015>, Embase <1980 to 2015 Week 16>, All Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>

Search Strategy:

| 1 | exp Rhinitis/ (95436) |

| 2 | (rhiniti* or rhinosinusiti* or poll?nosis or hay fever or hayfever or ((seasonal or inhalant* or respirat*) adj3 allerg*)).tw. (85040) |

| 3 | (grass* or tree or trees or pollen$1).tw. (261672) |

| 4 | or/1–3 (372633) |

| 5 | Skin Tests/ (64076) |

| 6 | exp Intradermal Tests/ (6027) |

| 7 | (((test or tests or testing) adj3 (skin or prick or passive transfer or intradermal or intercutaneous or epicutaneous or percutaneous or allerg* or provocat*)) or SPT or SPTs or IDST or IDSTs).tw. (95579) |

| 8 | Bronchial Provocation Tests/ (12348) |

| 9 | Nasal Provocation Tests/ (2731) |

| 10 | ((allerg* or provocat* or nasal or inhalant*) adj3 challenge*).tw. (12619) |

| 11 | Radioallergosorbent Test/ (9842) |

| 12 | (radioallergosorbent* or radioimmunosorbent* or RAST or RASTs).tw. (9708) |

| 13 | or/5–12 (158479) |

| 14 | “Sensitivity and Specificity”/ (516790) |

| 15 | “Predictive Value of Tests”/ (225688) |

| 16 | likelihood functions/ (131637) |

| 17 | False Positive Reaction/ (67227) |

| 18 | False Negative Reaction/ (58551) |

| 19 | (sensitivit* or specificit* or accurac* or validit* or valida* or predictive value* or PPV or NPV or likelihood ratio* or ROC curve* or AUC or (false adj positive*) or (false adj negative*)).tw. (3141298) |

| 20 | gold standard.ab. (96368) |

| 21 | or/14–20 (3658119) |

| 22 | 4 and 13 and 21 (5172) |

| 23 | (Comment or Editorial or Letter or Congresses).pt. (2809062) |

| 24 | 22 not 23 (5128) |

| 25 | 24 use pmoz,cctr,coch,dare,clhta,cleed (2434) |

| 26 | exp Rhinitis/ (95436) |

| 27 | (rhiniti* or rhinosinusiti* or poll?nosis or hay fever or hayfever or ((seasonal or inhalant* or respirat*) adj3 allerg*)).tw. (85040) |

| 28 | (grass* or tree or trees or pollen$1).tw. (261672) |

| 29 | or/26–28 (372633) |

| 30 | Allergy Test/ (3288) |

| 31 | Skin Test/ (64067) |

| 32 | Prick Test/ (14084) |

| 33 | Intracutaneous Test/ (2696) |

| 34 | (((test or tests or testing) adj3 (skin or prick or passive transfer or intradermal or intercutaneous or epicutaneous or percutaneous or allerg* or provocat*)) or SPT or SPTs or IDST or IDSTs).tw. (95579) |

| 35 | provocation test/ (24466) |

| 36 | nose provocation test/ (919) |

| 37 | ((allerg* or provocat* or nasal or inhalant*) adj3 challenge*).tw. (12619) |

| 38 | Radioallergosorbent Test/ (9842) |

| 39 | (radioallergosorbent* or radioimmunosorbent* or RAST or RASTs).tw. (9708) |

| 40 | or/30–39 (168806) |

| 41 | “sensitivity and specificity”/ (516790) |

| 42 | Diagnostic Accuracy/ (188623) |

| 43 | Diagnostic Test Accuracy Study/ (32579) |

| 44 | (sensitivit* or specificit* or accurac* or validit* or valida* or predictive value* or PPV or NPV or likelihood ratio* or ROC curve* or AUC or (false adj positive*) or (false adj negative*)).tw. (3141298) |

| 45 | gold standard.ab. (96368) |

| 46 | or/41–45 (3492743) |

| 47 | 29 and 40 and 46 (5134) |

| 48 | (Comment or Editorial or Letter or Conference abstract).pt. (4558513) |

| 49 | 47 not 48 (4433) |

| 50 | 49 use emez (2235) |

| 51 | 25 or 50 (4669) |

| 52 | limit 51 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,DARE; records were retained] (3913) |

| 53 | remove duplicates from 52 (2421) |

Economic Evidence Review

Database: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials <March 2015>, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews <2005 to March 2015>, EBM Reviews - Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects <1st Quarter 2015>, EBM Reviews - Health Technology Assessment <2nd Quarter 2015>, EBM Reviews - NHS Economic Evaluation Database <2nd Quarter 2015>, Embase <1980 to 2015 Week 18>, All Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>

Search Strategy:

| 1 | exp Rhinitis/ (95960) |

| 2 | (rhiniti* or rhinosinusiti* or poll?nosis or hay fever or hayfever or ((seasonal or inhalant* or respirat*) adj3 allerg*)).tw. (85555) |

| 3 | (grass* or tree or trees or pollen$1).tw. (262994) |

| 4 | or/1–3 (374545) |

| 5 | Skin Tests/ (64191) |

| 6 | exp Intradermal Tests/ (6038) |

| 7 | (((test or tests or testing) adj3 (skin or prick or passive transfer or intradermal or intercutaneous or epicutaneous or percutaneous or allerg* or provocat*)) or SPT or SPTs or IDST or IDSTs).tw. (96061) |

| 8 | Bronchial Provocation Tests/ (12369) |

| 9 | Nasal Provocation Tests/ (2740) |

| 10 | ((allerg* or provocat* or nasal or inhalant*) adj3 challenge*).tw. (12700) |

| 11 | Radioallergosorbent Test/ (9852) |

| 12 | (radioallergosorbent* or radioimmunosorbent* or RAST or RASTs).tw. (9723) |

| 13 | or/5–12 (159092) |

| 14 | economics/ (243928) |

| 15 | economics, medical/ or economics, pharmaceutical/ or exp economics, hospital/ or economics, nursing/ or economics, dental/ (684889) |

| 16 | economics.fs. (360344) |

| 17 | (econom* or price or prices or pricing or priced or discount* or expenditure* or budget* or pharmacoeconomic* or pharmaco-economic*).tw. (619355) |

| 18 | exp “costs and cost analysis”/ (476128) |

| 19 | cost*.ti. (213942) |

| 20 | cost effective*.tw. (221554) |

| 21 | (cost* adj2 (util* or efficacy* or benefit* or minimi* or analy* or saving* or estimate* or allocation or control or sharing or instrument* or technolog*)).ab. (138655) |

| 22 | models, economic/ (122793) |

| 23 | markov chains/ or monte carlo method/ (112924) |

| 24 | (decision adj1 (tree* or analy* or model*)).tw. (30140) |

| 25 | (markov or markow or monte carlo).tw. (89057) |

| 26 | quality-adjusted life years/ (25106) |

| 27 | (QOLY or QOLYs or HRQOL or HRQOLs or QALY or QALYs or QALE or QALEs).tw. (42575) |

| 28 | ((adjusted adj (quality or life)) or (willing* adj2 pay) or sensitivity analys*s).tw. (84617) |

| 29 | or/14–28 (2098653) |

| 30 | 4 and 13 and 29 (718) |

| 31 | (Comment or Editorial or Letter or Congresses).pt. (2821547) |

| 32 | 30 not 31 (706) |

| 33 | limit 32 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,DARE; records were retained] (642) |

| 34 | 33 use pmoz,cctr,coch,dare,clhta (242) |

| 35 | 4 and 13 (28516) |

| 36 | 35 use cleed (26) |

| 37 | 34 or 36 (268) |

| 38 | exp Rhinitis/ (95960) |

| 39 | (rhiniti* or rhinosinusiti* or poll?nosis or hay fever or hayfever or ((seasonal or inhalant* or respirat*) adj3 allerg*)).tw. (85555) |

| 40 | (grass* or tree or trees or pollen$1).tw. (262994) |

| 41 | or/38–40 (374545) |

| 42 | Allergy Test/ (3311) |

| 43 | Skin Test/ (64182) |

| 44 | Prick Test/ (14238) |

| 45 | Intracutaneous Test/ (2705) |

| 46 | (((test or tests or testing) adj3 (skin or prick or passive transfer or intradermal or intercutaneous or epicutaneous or percutaneous or allerg* or provocat*)) or SPT or SPTs or IDST or IDSTs).tw. (96061) |

| 47 | provocation test/ (24563) |

| 48 | nose provocation test/ (928) |

| 49 | ((allerg* or provocat* or nasal or inhalant*) adj3 challenge*).tw. (12700) |

| 50 | Radioallergosorbent Test/ (9852) |

| 51 | (radioallergosorbent* or radioimmunosorbent* or RAST or RASTs).tw. (9723) |

| 52 | or/42–51 (169481) |

| 53 | 41 and 52 (29275) |

| 54 | Economics/ (243928) |

| 55 | Health Economics/ or exp Pharmacoeconomics/ (206815) |

| 56 | Economic Aspect/ or exp Economic Evaluation/ (368187) |

| 57 | (econom* or price or prices or pricing or priced or discount* or expenditure* or budget* or pharmacoeconomic* or pharmaco-economic*).tw. (619355) |

| 58 | exp “Cost”/ (476128) |

| 59 | cost*.ti. (213942) |

| 60 | cost effective*.tw. (221554) |

| 61 | (cost* adj2 (util* or efficacy* or benefit* or minimi* or analy* or saving* or estimate* or allocation or control or sharing or instrument* or technolog*)).ab. (138655) |

| 62 | Monte Carlo Method/ (45596) |

| 63 | (decision adj1 (tree* or analy* or model*)).tw. (30140) |

| 64 | (markov or markow or monte carlo).tw. (89057) |

| 65 | Quality-Adjusted Life Years/ (25106) |

| 66 | (QOLY or QOLYs or HRQOL or HRQOLs or QALY or QALYs or QALE or QALEs).tw. (42575) |

| 67 | ((adjusted adj (quality or life)) or (willing* adj2 pay) or sensitivity analys*s).tw. (84617) |

| 68 | or/54–67 (1718656) |

| 69 | 53 and 68 (698) |

| 70 | (Comment or Editorial or Letter or Conference abstract).pt. (4591102) |

| 71 | 69 not 70 (613) |

| 72 | limit 71 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,DARE; records were retained] (552) |

| 73 | 72 use emez (292) |

| 74 | 37 or 73 (560) |

| 75 | remove duplicates from 74 (433) |

Appendix 3: Criteria for Grading the Quality of Evidence in Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy

Table 2|.

Factors that decrease quality of evidence for studies of diagnostic accuracy and how they differ from evidence for other interventions

| Factors that determine and can decrease quality of evidence | Explanations and differences from quality of evidence for other interventions |

|---|---|

| Study design | Different criteria for accuracy studies—Cross sectional or cohort studies in patients with diagnostic uncertainty and direct comparison of test results with an appropriate reference standard are considered high quality and can move to moderate, low, or very low depending on other factors |

| Limitations (risk of bias) | Different criteria for accuracy studies—Consecutive patients should be recruited as a single cohort and not classified by disease state, and selection as well as referral process should be clearly described.7 Tests should be done in all patients in the same patient population for new test and well described reference standard; evaluators should be blind to results of alternative test and reference standard |

| Indirectness: | |

| Outcomes | Similar criteria—Panels assessing diagnostic tests often face an absence of direct evidence about impact on patient-important outcomes. They must make deductions from studies of diagnostic tests about the balance between the presumed influences on patient-important outcomes of any differences in true and false positives and true and false negatives in relation to complications and costs of the test. Therefore, accuracy studies typically provide low quality evidence for making recommendations owing to indirectness of the outcomes, similar to surrogate outcomes for treatments |

| Patient populations, diagnostic test, comparison test, and indirect comparisons | Similar criteria—Quality of evidence can be reduced if important differences exist between populations studied and those for whom recommendation is intended (in previous testing, spectrum of disease or comorbidity); if Important differences exist in tests studied and diagnostic expertise of people applying them in studies compared with settings for which recommendations are intended; or if tests being compared are each compared with a reference (gold) standard in different studies and not directly compared in same studies |

| Important inconsistency in study results | Similar criteria—For accuracy studies, unexplained inconsistency in sensitivity, specificity, or likelihood ratios (rather than relative risk or mean differences) can reduce quality of evidence |

| Imprecise evidence | Similar criteria—For accuracy studies, wide confidence intervals for estimates of test accuracy or true and false positive and negative rates can reduce quality of evidence |

| High probability of publication bias | Similar criteria—High risk of publication bias (for example, evidence from small studies for new intervention or test, or asymmetry in funnel plot) can lower quality of evidence |

Reproduced from GRADE: grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies, Schünemann A, Oxmann A, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist G, et al., Vol. 336, pp. 1106–10, Copyright 2008 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Appendix 4: Critical Evaluation of Included Studies, Using Modified Methodological Checklist for Economic Evaluations

| Question: What is the cost-effectiveness of skin tests for allergic rhinitis? | ||

| Study reference: Lewis AF 2008 (27) | ||

| Checklist completed by: Brian Chan | ||

| APPLICABILITY (relevance to question under review) | ||

| Item | Yes/Partly/No/Unclear/Not Applicable | Comments |

| Is the study population appropriate to the question? | Yes | |

| Are the interventions appropriate to the question? | Yes | |

| Are all relevant interventions compared? | Yes | |

| What country was this study conducted in? | United States | |

| Is the health care system in which the study was conducted sufficiently similar to Ontario with respect to this question/topic? Explain the ways in which they differ. | Yes | |

| Are estimates of relative treatment effect the same as those included in the clinical evidence review? | Yes | |

| Are costs measured from a health care payer perspective? | Unclear | |

| Are non-direct health effects on individuals excluded? | Not applicable | |

| Are both costs and health effects discounted at an annual rate of 5%? | Not applicable | |

| Do the estimates of resource use differ from that which would be expected in an Ontario context? | No | |

| Is the value of health expressed in terms of quality-adjusted life years? | No | |

| Are changes in health-related quality of life (HRQL) obtained directly from patients and/or caregivers? | Not applicable | |

| Has the valuation of changes in HRQL (utilities) been obtained from a representative sample of the general public? | Not applicable | |

|

Overall judgment (directly applicable/partially applicable/not applicable): not applicable If a study is considered not applicable, there is no need to assess its quality. | ||

Adapted from: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2012. (26)

Author contributions

This report was developed by a multi-disciplinary team from Health Quality Ontario. The lead clinical epidemiologist was Conrad Kabali, the lead health economist was Brian Chan, the medical librarians were Caroline Higgins and Corinne Holubowich.

KEY MESSAGES

Allergic rhinitis, also called hay fever, is the most common type of allergy, affecting about 20% to 25% of Canadians. The condition includes allergies to pollen, dust mites, mould, pet dander and other common indoor and outdoor substances. These allergies cause cold-like symptoms such as runny nose, itchy eyes and sneezing.

Two types of skin tests—skin-prick testing and intradermal testing—are used to find out what substances (allergens) people are allergic to. Both tests involve inserting a drop of an allergen under the skin, either by scratching it or using a needle to inject the allergen between layers of the skin, to see if it creates a small rash-like reaction. Each year in Ontario, about two million skin tests for allergic rhinitis are funded through the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. A patient may get many skin tests at the same time, since each test is for a different allergen.

Although these tests are common, there are questions about how accurate they are. The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care asked Health Quality Ontario to assess the accuracy and cost-effectiveness of skin tests for allergic rhinitis and to estimate the cost of continuing to fund them.

We found 12 studies that evaluated the accuracy of skin tests for allergic rhinitis. Eight studies were on skin-prick testing and they showed that, on average, this type of test was moderately accurate: it was able to correctly identify 85% of people with allergic rhinitis and 77% of people without the condition. For intradermal testing, the number of studies and the number of patients involved were too small to allow us to assess the overall accuracy of that test. We did not find any studies relevant to Ontario that reported on the cost-effectiveness of skin tests for allergic rhinitis.

Our analysis of the costs of this allergy testing in Ontario showed that public funding of skin tests for allergic rhinitis costs the health system between $2.5 million and $3.0 million per year for the tests alone, not including the cost of the visits to the doctor where the testing takes place.

Contributor Information

Health Quality Ontario:

Conrad Kabali, Brian Chan, Caroline Higgins, and Corinne Holubowich

About Health Quality Ontario

Health Quality Ontario is the provincial advisor on the quality of health care. We are motivated by a single-minded purpose: Better health for all Ontarians.

Who We Are

We are a scientifically rigorous group with diverse areas of expertise. We strive for complete objectivity, and look at things from a vantage point that allows us to see the forest and the trees. We work in partnership with health care providers and organizations across the system, and engage with patients themselves, to help initiate substantial and sustainable change to the province's complex health system.

What We Do

We define the meaning of quality as it pertains to health care, and provide strategic advice so all the parts of the system can improve. We also analyze virtually all aspects of Ontario's health care. This includes looking at the overall health of Ontarians, how well different areas of the system are working together, and most importantly, patient experience. We then produce comprehensive, objective reports based on data, facts and the voice of patients, caregivers and those who work each day in the health system. As well, we make recommendations on how to improve care using the best evidence. Finally, we support large scale quality improvements by working with our partners to facilitate ways for health care providers to learn from each other and share innovative approaches.

Why It Matters

We recognize that, as a system, we have much to be proud of, but also that it often falls short of being the best it can be. Plus certain vulnerable segments of the population are not receiving acceptable levels of attention. Our intent at Health Quality Ontario is to continuously improve the quality of health care in this province regardless of who you are or where you live. We are driven by the desire to make the system better, and by the inarguable fact that better has no limit.

REFERENCES

- (1).World Allergy Organization. WAO white book on allergy: update 2013 executive summary [Milwaukee (WI): WAO; 2013. [cited 2015 Jul 28]. 242 p. Available from: http://www.worldallergy.org/definingthespecialty/white_book.php. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Blaiss MS. Allergic rhinitis: direct and indirect costs. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(5):375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Wheatley LM, Togias A. Allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):456–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Long A, McFadden C, DeVine D, Chew P, Kupelnick B, Lau J. Management of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. Rockville (MD): 2002. 54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bernstein IL, Li JT, Bernstein DI, Hamilton R, Spector SL, Tan R, et al. Allergy diagnostic testing: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(3):S1–S148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Fatteh S, Rekkerth D, Hadley JA. Skin prick/puncture testing in North America: a call for standards and consistency. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2014;10(44):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Simons JP, Rubinstein EN, Kogut VJ, Melfi PJ, Ferguson BJ. Comparison of Multi-Test II skin prick testing to intradermal dilutional testing. Otolaryng Head Neck. 2004;130(5):536–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wells GA, Elliot J, Kelly S, Johnston A, Skidmore B, Kofsky J. Allergen immunotherapy for the treatment of allergic rhinitis and/or asthma: final systematic review report [Toronto (ON): Ontario Drug Policy Research Network; 2015. [cited 2015 Sept 23]. 52 p. Available from: http://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Allergen-Immunotherapy_Systematic-Review-Report_Oct-1-2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz A, Denburg J, Fokkens W, Togias A, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008. Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;63(s86):8–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Skoner DP. Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S2–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Derebery MJ, Mahr TA, Gordon BR, Sheth KT, et al. Burden of allergic rhinitis: results from the pediatric allergies in America survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(S43–S70). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Keith PK, Desrosiers M, Laister T, Schellenberg RR, Waserman S. The burden of allergic rhinitis (AR) in Canada: perspectives of physicians and patients. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2012;8(7):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AWS, Scholten RJPM, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:982–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Whiting P, Rutjes A, Westwood M, Mallett S, Deeks J, Reitsma J, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Schünemann A, Oxmann A, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist G, et al. GRADE: grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336:1106–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Krouse JH, Shah AG, Kerswill K. Skin testing in predicting response to nasal provocation with alternaria. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(8):1389–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gungor A, Houser SM, Aquino BF, Akbar I, Moinuddin R, Mamikoglu B, et al. A comparison of skin endpoint titration and skin-prick testing in the diagnosis of allergic rhinitis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83(1):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Pepys J, Roth A, Carroll KB. RAST, skin and nasal tests and the history in grass pollen allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 1975;5(4):431–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Petersson G, Dreborg S, Ingestad R. Clinical history, skin prick test and RAST in the diagnosis of birch and timothy pollinosis. Allergy. 1986;41(6):398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wood RA, Phipatanakul W, Hamilton RG, Eggleston PA. A comparison of skin prick tests, intradermal skin tests, and RASTs in the diagnosis of cat allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(5 I):773–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zarei M, Remer CF, Kaplan MS, Staveren AM, Lin CKE, Razo E, et al. Optimal skin prick wheal size for diagnosis of cat allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92(6):604–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Krouse JH, Sadrazodi K, Kerswill K. Sensitivity and specificity of prick and intradermal testing in predicting response to nasal provocation with timothy grass antigen. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(3):215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Haahtela T, Burbach GJ, Bachert C, Bindslev-Jensen C, Bonini S, Bousquet J, et al. Clinical relevance is associated with allergen-specific wheal size in skin prick testing. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44(3):407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Pastorello EA, Codecasa LR, Pravettoni V, Qualizza R, Incorvaia C, Ispano M, et al. Clinical reliability of diagnostic tests in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Boll Ist Sieroter Milan. 1988;67(5–6):377–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Process and methods guides. The guidelines manual: appendix G: methodology checklist [London (UK): National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2012. [cited 2015 May 27]. p. Available from: http://publications.nice.org.uk/the-guidelines-manual-appendices-bi-pmg6b/appendix-g-methodology-checklist-economic-evaluations. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lewis AF, Franzese C, Stringer SP. Diagnostic evaluation of inhalant allergies: a cost-effectiveness analysis. American journal of rhinology. 2008;22(3):246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan. Medical price list as of 01 April 2015 [Alberta: Alberta Health; 2015. [cited 2015 Jul 28]. 751 p. Available from: http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/SOMB-Medical-Prices-2015-04.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Manitoba Minister of Health. Manitoba physician's manual [Manitoba: Manitoba health, healthy living and seniors; 2015 Apr. [cited 2015 Jul 28]. 445 p. Available from: http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/documents/physmanual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Schedule of benefits: physician services under the Health Insurance Act [Toronto (ON): Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2015. [cited 2015 Jul 28]. 750 p. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohip/sob/physserv/sob_master11062015.pdf. [Google Scholar]