Abstract

We report the case of a 16-year-old female with genetic immunodeficiency in whom pulmonary coccidioidomycosis became disseminated. Most infections due to Coccidioides immitis are self-limited and resolve over a period of weeks to months without specific treatment. In rare cases, especially those associated with immunodeficiency, the disease is found outside the confines of the chest cavity. In these cases, the most common site of dissemination is the skin. Defining the extent of dissemination often relies on diagnostic imaging.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Coccidioidomycosis is a disease endemic to the San Joaquin Valley of California, the southwestern United States, and northern Mexico. Most infections due to Coccidioides immitis are self-limited and resolve over a period of weeks to months without specific treatment. In rare cases, especially those associated with immunodeficiency, the disease is found outside the confines of the chest cavity. Estimates of this risk vary from approximately 4.7 percent of recognized infections (Einstein, HE et al., presented at Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases) (1) to 0.2 percent of all respiratory exposures to Coccidioides (2). The wide range in estimates is likely due to the under-recognition of mild infections.

Immunodeficiency from diseases like HIV infection or Hodgkin’s lymphoma dramatically increases a patient’s risk for dissemination. Additionally, such immunosuppressive drugs as high-dose corticosteroid therapy or anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy increase an individual’s risk for dissemination. Solid tumor and hematologic transplant patients are more likely to have disseminated disease as well. This is most likely due to an immunosuppressed state and not to transplantation of an infected organ, although such occurrences have been documented (3). Pregnancy can also increase a patient’s risk, due to a transient state of immunosuppression, which occurs particularly in the third trimester (4). Other patient demographic groups at risk for extrapulmonary complications include males and those of African or Filipino ancestry.

Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis typically disseminates through the lymphatic system, as hilar adenopathy is a common feature of coccidioidal pneumonia, and progression of infections to paratracheal and supraclavicular nodes before the development of extrapulmonary lesions is well documented. The most common sites of extrapulmonary dissemination include skin or subcutaneous tissue, the meninges, or the skeleton (5, 6). Other common sites include the endocrine glands (7, 8), the eye (9, 10, 11), the liver (12), the kidneys (13), the genital organs (14, 15, 16, 17, 18), the prostate (19, 20), and the peritoneal cavity [21].

Often Coccidioides immitis infection is clinically silent, and the extent of dissemination may be underrecognized. Careful evaluation by such radiologic techniques as computed tomography (CT) and nuclear medicine bone scintography can reveal extensive spread of coccidioidomycosis and greatly aid diagnosis and management. We report such imaging findings in a case of disseminated coccidioidomycosis in an immunologically compromised pediatric patient.

Case report

A 16-year-old previously healthy female presented to this hospital with a two-year history of treatment-refractory tinea capitus of the scalp, left ear, and neck. At that time, she denied fever, malaise, arthralgia, fatigue, weight loss, or any other constitutional symptoms. She further denied cough, shortness of breath, or dyspnea. Her tinea capitus ultimately was treated successfully by terbinafine after failing several other antifungal regimens.

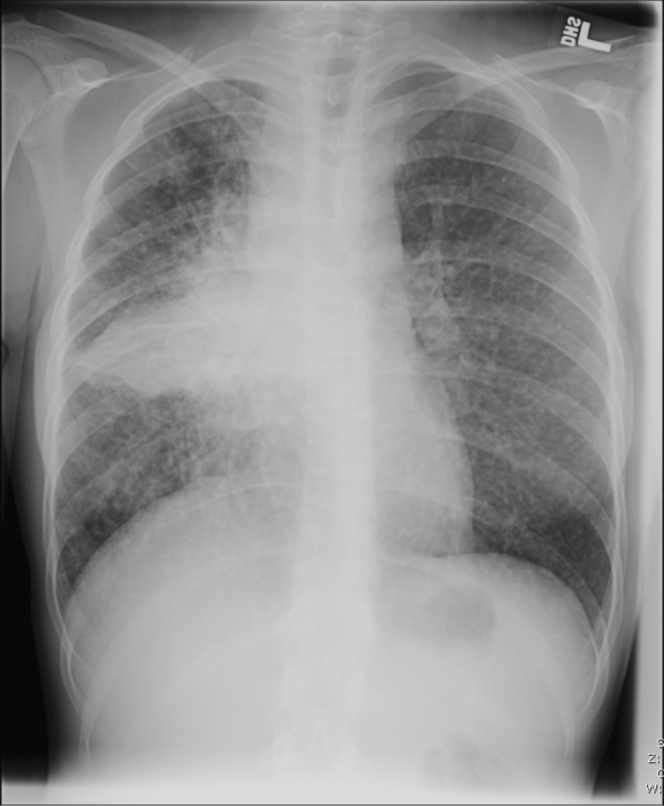

Figure 1.

16-year-old female with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Chest radiograph demonstrates widespread pulmonary disease with associated lymphadenopathy consistent with pulmonary coccidoidomycosis. Multiple small nodules demonstrated throughout all the lobes of both lungs. There is extensive consolidation in the right lower lobe and marked mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy. There are no pleural effusions. The heart size is normal.

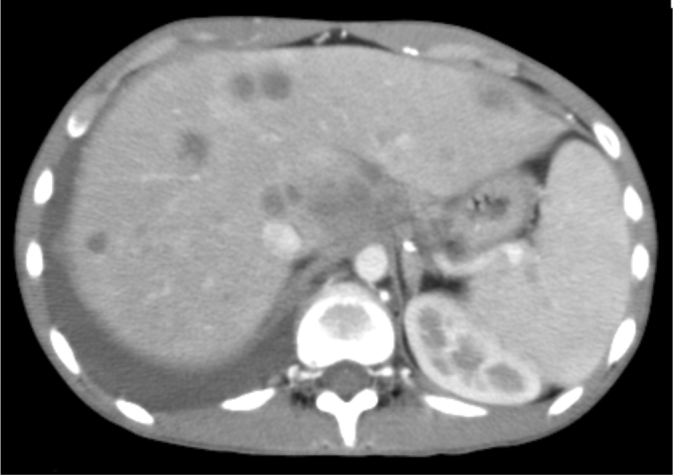

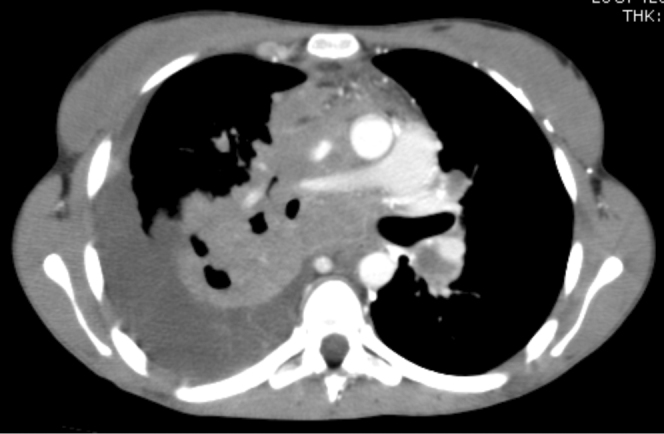

Figure 2.

16-year-old female with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. CT of the chest and abdomen with contrast. (A) Multiple necrotic portocaval lymph nodes are shown here. Mild narrowing of the proximal superior vena cava by the necrotic mass is seen within the mediastinum. A necrotic enhancing soft-tissue mass occupies the majority of the mediastinum above the heart. This mass represents a confluence of necrotic lymphadenopathy. It is compressing the superior vena cava proximally, but the vessel remains patent. The conglomerate soft-tissue mass in the mediastinum is also pushing the pulmonary artery and aorta to the left, causing elongation and narrowing of the right pulmonary artery, and is partially compressing the right bronchus as well. (B) This chest CT demonstrates numerous hypodense nodules in the liver and in the spleen that represent foci of coccidioidomycosis infection. The abnormal enhancement of the liver is likely related to SVC compression. (C) Multiple cystic structures demonstrated within the spleen.

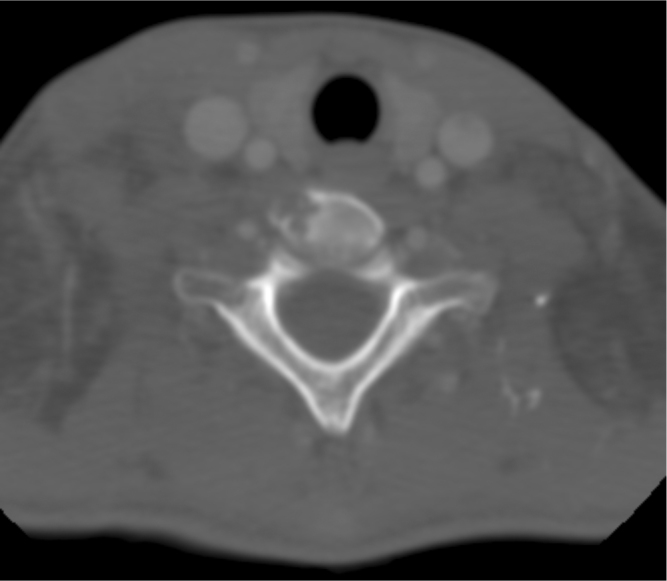

Figure 3.

16-year-old female with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. CT of the neck with contrast. There is evidence of osteomyelitis within the vertebral body of C6, without evidence of spinal cord invasion.

One year later, the patient presented again to this hospital with an eight-month history of chronic cough with decreased energy, a 15-pound weight loss, and cervical lymphadenopathy. During the three months before admission, she developed a right-sided neck mass that had been nontender and not inflamed. She was afebrile. She had been seen by her primary care physician and subsequently referred for a biopsy of the neck mass about two weeks before admission. A chest radiograph showed diffuse, widespread pulmonary disease with associated lymphadenopathy. Pathologic analysis of the cervical lymph node biopsy demonstrated findings consistent with Coccidioides infection. Serology also revealed a coccidioidal antigen antibody titer of 1:128 (no antibodies are detected in normal individuals). The patient had a negative Purified Protein Derivative (PPD) tuberculosis test.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast revealed bilateral pleural effusions and multiple small pulmonary nodules seen throughout all pulmonary lobes. Cavitation was seen in a right lower lobe consolidation, with the formation of a bronchopleural fistula. Moderate compression of the superior vena cava and right pulmonary artery were noted, but no intraluminal filling defects were observed. An enlarged and presumably infected right inferior sternocleidomastoid muscle was also noted. Additionally, the patient had significant hepatosplenomegaly with diffuse calcifications dispersed throughout the liver and spleen. A periportal mass was also observed. The kidneys bilaterally had multiple calcified lesions, and a necrotic node was noted in the peritoneum. Additionally, there were multiple retroperitoneal and mesenteric node calcifications. Free fluid was seen in the right pericolic gutter, within the pelvis and bilateral lower quadrants. Multiple lytic lesions were visualized within the right clavicle and right aspect of the T6 vertebral body, the right T5 vertebral body, the sternum, and the right transverse process of the T10 vertebra. Spina bifida was observed at S1. The bowel appeared normal in caliber and free of involvement. The pancreas, adrenal glands, gallbladder, and bladder also appeared unremarkable.

CT of the head further revealed incidental bilateral basal ganglia calcifications, but was otherwise unremarkable. There was no definite acute intracranial hemorrhage or territorial infarct. There was no mass effect or hydrocephalus. The orbits and paranasal sinuses were within normal limits. No suspicious focal osseous lesions were present. CT of the sinuses and orbits revealed mucous retention cysts involving the left maxillary and right sphenoid sinuses, without air-fluid levels to suggest acute infection. In the context of this patient’s presentation with chronic cough, immune deficiency, negative PPD, and residence in southern Arizona, the imaging findings presented here are most consistent with disseminated coccidioidomycosis infection.

Since this admission, the patient’s condition has improved considerably. The patient initially required a gastric tube for feeds, but has since had the tube removed and is now feeding orally and maintaining a normal body weight. The patient is currently maintained on prophylactic Posaconazole (a triazole with more efficacy than fluconazole or itraconazole in the prevention of fungal infections) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for her immunodeficiency. Followup imaging has not been conducted. The exact cause of the patient’s immunodeficiency remains undetermined. Several laboratory results for specific known causes of immunodeficiency returned negative or unequivocal during her hospital stay. At the time of publication, the Infectious Disease group was following the case closely and preparing to send the patent to Bethesda, Maryland to the National Institutes of Health for further genetic testing.

Discussion

Twenty percent of acutely symptomatic patients infected with Coccidiomyces have no radiological findings or demonstrate only soft hazy, patchy, segmental, pneumonic opacities. Most patients, however, demonstrate some airspace opacities and regional lymphadenopathy. Associated hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy demonstrates parenchymal involvement that occasionally can result in pleural effusions on chest radiograph. Both airspace opacities and regional lymphadenopathy usually resolve within several weeks. Residual calciferous opaque foci can appear later in the sites of both pulmonary and lymph node involvement (22, 23, 24).

Radiographically, the lesion of acute coccidioidomycosis appears similar to the primary opacity noted in primary tuberculosis—its duration is typically much shorter than that of tuberculosis, however. A definitive diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis can be achieved only by positive sputum culture, positive reaction to coccidiodin skin test, or coccidioidal serology (22, 23).

Patients with symptoms or radiographic findings that persist beyond 6–8 weeks of acute infection often demonstrate solitary or multiple cavitary “coin lesions” or “coccidioidomas,” approximately 4cm in diameter, which are often found in the upper or middle lobes. Patients with such findings demonstrate persistent coccidioidomycosis. These lesions occasionally liquefy and drain into a bronchus to form a cavity, like the one seen in the case described here. Cavities are usual peripheral, solitary, and asymptomatic, and resolve spontaneously within two years. Occasionally, patients have persistent pleuritic pain and hemoptysis due to these cavities, and rarely cavities can burst and drain into the pleural space, causing a life-threatening spontaneous pneumothorax (25). These findings of persistent coccidioidomycosis are less common in the pediatric population discussed here (22).

The classic findings in chronic coccidioidomycosis are biapical, fibronodular, 2–4cm thin- or thick-walled cavitary lesions in the upper lung fields that often result in retraction of lung parenchyma. This chronic fibrotic pneumonic process is seen commonly in patients with diabetes or smokers with chronic disease (26). In disseminated cases, coccidioidomycosis can develop a miliary appearance similar to that of tuberculosis, and patients commonly will have similar symptoms such as night sweats, weight loss, and local symptoms (22).

Skin infection is the most common site of pulmonary dissemination (27). Although the route of disseminated coccidioidomycosis is presumably primarily through pulmonary inoculation, many patients with disseminated coccidioidal infection have entirely normal chest radiographs at presentation. Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy often may be the only remaining sign of pulmonary infection.

Vertebral involvement is common in disseminated coccidioidomycosis, and lesions often coalesce into anterior or posterior paraspinous abscesses. Neither was noted in this case, likely because spinal involvement was not contiguous along the vertebral column (28). Osteomyelitis of the peripheral skeleton typically affects the epiphysis of long bones. Nuclear medicine bone scan is the preferred modality to demonstrate the extent of vertebral involvement. These studies may lose usefulness through the course of the patient’s disease, as bone scans rarely return to normal even after infection has resolved (29).

Meningeal involvement is the most dreaded complication of extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Common presenting symptoms are headache, nausea, and vomiting. Symptoms of meningeal coccidioidomycosis tend to develop in subacute fashion, usually within six months of initial infection according to several studies (30, 31). Death usually results within two years of diagnosis. Coccidioidal meningitis commonly affects the basilar region of the brain, frequently causing obstructive hydrocephalus. Although head CT may demonstrate ventriculomegaly, the preferred neuro-imaging modality is MRI, to better define extent of basilar involvement.

Conclusion

Careful evaluation by several radiologic techniques as radiography, CT, MRI, and nuclear imaging can reveal extensive spread of coccidioidomycosis and greatly aid diagnosis and management, as was demonstrated in this case report. Although our patient experienced several prolonged hospitalizations due to complications of her disseminated coccidioidomycosis, her disease is currently well controlled with antifungal therapy. Radiologic evaluation reveals the extent of her disease and is continually used to guide therapy. This case serves to demonstrate the benefit of appropriate radiologic evaluation in patients with concern for disseminated coccidioidomycosis and further serves to clarify such radiologic manifestations of this challenging disease.

Footnotes

Published: October 15, 2008

Contributor Information

Ian L. Musil, Email: musil@email.arizona.edu.

Dorothy Gilbertson-Dahdal, Email: dgilbertson@radiology.arizona.edu.

Sean P. Elliott, Email: elliotts@email.arizona.edu.

References

- 1.Johnson RH, Caldwell JW, Welch G, Einstein HE. The great coccidioidomycosis epidemic: Clinical features. In: Einstein HE, Catanzaro A, editors. Coccidioidomycosis. Proceedings of the 5th international conference. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases; Washington: 1996. p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnato AE, Sanders GD, Owens DK. Cost-effectiveness of a potential vaccine for Coccidioides immitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:797. doi: 10.3201/eid0705.010505. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripathy U, Yung GL, Kriett JM. Donor transfer of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis in lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002:306–308. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02723-0. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson CM, Schuppert K, Kelly PC. Coccidioidomycosis and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48:149–156. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199303000-00002. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhn J, Slovis T, Haller J. Caffey's pediatric diagnostic. tenth edition 2005. Elsevier; New York, NY: 2005. Coccidioidomycosis; pp. 1017–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galgiani JN. Coccidioidomycosis. West J Med. 1993;159:153. [PubMed] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crum NF, Lederman ER, Stafford CM. Coccidioidomycosis: A descriptive survey of a reemerging disease. Clinical characteristics and current controversies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:149. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000126762.91040.fd. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papadopoulos KI, Castor B, Klingspor L. Bilateral isolated adrenal coccidioidomycosis. J Intern Med. 1996;239:275. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.407760000.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smilack JD, Argueta R. Coccidioidal infection of the thyroid. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:89. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.1.89. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodenbiker HT, Ganley JP. Ocular coccidioidomycosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;24:263. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(80)90056-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham ET, Jr, Seiff SR, Berger TG. Intraocular coccidioidomycosis diagnosed by skin biopsy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:674. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.5.674. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone JL, Kalina RE. Ocular coccidioidomycosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:249. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71302-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg B, Loeffler AM. Respiratory distress and a liver mass. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:1105. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199912000-00018. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huntington RW. Pathology of coccidioidomycosis. In: Stevens DA, editor. Coccidioidomycosis: A text. Plenum Medical Book Co; New York: 1980. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuntze JR, Herman MH, Evans SG. Genitourinary coccidioidomycosis. J Urol. 1988;140:370. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41611-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao JC, Reiter RE. Coccidioidomycosis presenting as testicular mass. J Urol. 2001;166:1396. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dykes TM, Stone AB, Canby-Hagino ED. Coccidioidomycosis of the epididymis and testis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:552. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.2.01840552. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halsey ES, Rasnake MS, Hospenthal DR. Coccidioidomycosis of the male reproductive tract. Mycopathologia. 2005;159:199. doi: 10.1007/s11046-004-6260-0. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohail MR, Andrews PE, Blair JE. Coccidioidomycosis of the male genital tract. J Urol. 2005;173:1978. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158455.24193.12. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrence MA, Ginsberg D, Stein JP. Coccidioidomycosis prostatitis associated with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 1999;84:372. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00226.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niku SD, Dalgleish G, Devendra G. Coccidioidomycosis of the prostate gland. Urology. 1998;52:127. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00152-6. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips P, Ford B. Peritoneal coccidioidomycosis: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:971. doi: 10.1086/313808. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briant W, Helms C. Fundamentals of diagnostic radiology. Third edition 2006. Elsevier; New York, NY: 2006. Coccidioidomycosis; pp. 469–470. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katzenstein, Askin . Surgical pathology of non-neoplastic lung disease. Fourth edition. Elsevier; Syracuse: 2006. Coccidioidomycosis; pp. 312–313. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunningham RT, Einstein H. Coccidioidal pulmonary cavities with rupture. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982;84:172–177. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarosi GA, Parker JD, Doto IL. Chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. N England J Med. 1970;283:325–329. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197008132830701. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galgiani J. Principals and practices of infectious disease by Mandell, Bennett, and Dolin. Elservier; Philadelphia: 2005. 2005. Coccidioides species; pp. 3040–3050. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erly WK, Carmody RF, Seeger JF. Magnetic resonance imaging of coccidioidal spondylitis. Int J Neuroradiol. 1997;3:385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno AJ, Weisman IM, Rodriguez AA. Nuclear imaging in coccidiodal osteomyelitis. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 1987;12(8):604–609. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198708000-00005. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Einstein HE, Holeman CW, Jr, Sandidge LL. Coccidioidal meningitis. The use of amphotericin B in treatment. Calif Med. 1961;94:339–343. [PubMed] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vincent T, Galgiani JN, Huppert M. The natural history of coccidioidal meningitis: VA-Armed Forces Cooperative Studies, 1955-1958. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:247–254. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.2.247. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]