Abstract

Phase-change materials exhibit fast and reversible transitions between an amorphous and a crystalline state at high temperature. The two states display resistivity contrast, which is exploited in phase-change memory devices. The technologically most important family of phase-change materials consists of Ge-Sb-Te alloys. In this work, we investigate the structural, electronic and kinetic properties of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 as a function of temperature by a combined experimental and computational approach. Understanding the properties of this phase is important to clarify the amorphization and crystallization processes. We show that the structural properties of the models obtained from ab initio and reverse Monte Carlo simulations are in good agreement with neutron and X-ray diffraction experiments. We extract the kinetic coefficients from the molecular dynamics trajectories and determine the activation energy for viscosity. The obtained value is shown to be fully compatible with our viscosity measurements.

Due to continuously increasing demand on high-density and fast data-storage devices, the interest in phase-change materials (PCMs) and their applications in non-volatile data storage media is extremely high1,2,3. The first work on PCMs dates back to 1968, when Ovshinsky reported on a sharp transition from high resistivity to low resistivity in amorphous Te48As30Si12Ge10 induced by an electric field (electric switching)4. However, another property of PCMs – the large contrast in the optical reflectivity between the amorphous and crystalline state – led to practical applications in the data storage media, namely in rewritable optical discs such as CDs, DVDs and Blu-ray discs. Many such devices are based on the Ge-Sb-Te (GST) PCM alloys from the pseudo-binary line between GeTe and Sb2Te3 compounds, discovered by Yamada et al.5.

Recently, the development of the phase-change random access memory (PCRAM) has sparked renewed interest in the electric switching phenomenon. PCRAMs exploit the electronic contrast between the amorphous and crystalline state. It is plausible that these non-volatile devices will be able to outperform and replace the Flash memory, whose miniaturization will soon come to an end due to physical limits. At present, GST alloys are among the most promising PCMs for high-speed, high-reliability PCRAMs. In spite of intensive studies, however, a complete understanding of the switching phenomena and the property contrast at the atomic level, which is required for the development of new, better performing data-storage media, is still lacking. Furthermore, the elucidation of the relations between the chemical composition, atomic structure, bonding mechanism and resulting phase-change properties remains a challenge for physicists and material scientists.

Apart from the technological importance of PCMs, the peculiar combination of physical properties of the crystalline, amorphous and liquid state is of great scientific interest too1,2,3. During the last years, significant progress has been made in the theoretical and experimental investigation of both crystalline6,7,8 and amorphous9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 GST alloys, while our knowledge of the structural and dynamical properties of the liquid state is more limited19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. In particular, there are still open questions about the crystalline-to-amorphous (amorphization) and amorphous-to-crystalline (devitrification) phase transitions, which can be clarified only by a detailed study of the liquid state. In PCM-based devices, the amorphization process occurs due to local melting (by a laser or current pulse) and subsequent quenching from the melt. It has been recently understood29,30,31,32 that the high fragility of the supercooled liquid state of PCMs plays a key role in the devitrification process. Fragility describes the deviation of the temperature dependence of the viscosity η from the Arrhenius behaviour. The high fragility of PCMs is responsible for two essential properties of PCMs, namely the rapid crystallization at high temperature and the high stability of the amorphous phase at room temperature. Hence, knowledge of the atomic structure and the dynamics of Ge-Sb-Te alloys in the liquid and supercooled liquid state is indispensable for a complete comprehension of the phase-change processes.

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations based on density functional theory (DFT) have been shown to yield models of PCMs which, overall, are in good agreement with experimental data. For standard generalized-gradient-approximation (GGA) functionals, the main discrepancy is the fact that the bond distances in liquid and amorphous PCMs are typically overestimated by 1–3%. A number of studies, including some of our own works12,13,33,34,35,36,37, have shown that the complementary information provided by different experimental techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), neutron diffraction (ND) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) can be effectively combined and interpreted in the frame of the reverse Monte-Carlo (RMC) simulation method38. In particular, in refs 12,13, the RMC method was used to analyse XRD, ND and EXAFS data for amorphous Ge1Sb2Te4 and Ge2Sb2Te5 alloys. These studies have provided very detailed information on the local atomic structure of these amorphous systems.

In this work, we investigate the atomic ordering in the liquid phase of Ge2Sb2Te5, as well its electronic and kinetic properties, by combining AIMD simulations with experiments and RMC simulations. We use AIMD and a van der Waals density functional which includes non-local correlations39 (denoted as vdW-DF2) to generate long trajectories at different temperatures, from which we extract the structural properties (including structure factors, pair and three-body correlation functions, and ring statistics), the electronic structure and the viscosity coefficients of the liquid state. These quantities are compared with experimental XRD data, neutron diffraction with Ge isotopic substitution data, and viscosity measurements. The AIMD structural models are also taken as input for refined RMC simulations. We show that the agreement between simulations and experiments is quite good. In particular, the mismatch between experimental and theoretical atomic distances is partially cured by the use of the vdW-DF2 functional and the temperature dependence of the activation energy for the viscosity matches the experimental value nicely. We also discuss the discrepancies in the magnitude of the viscosity in relation to the approximations made in our simulations.

Results

Structural and electronic properties

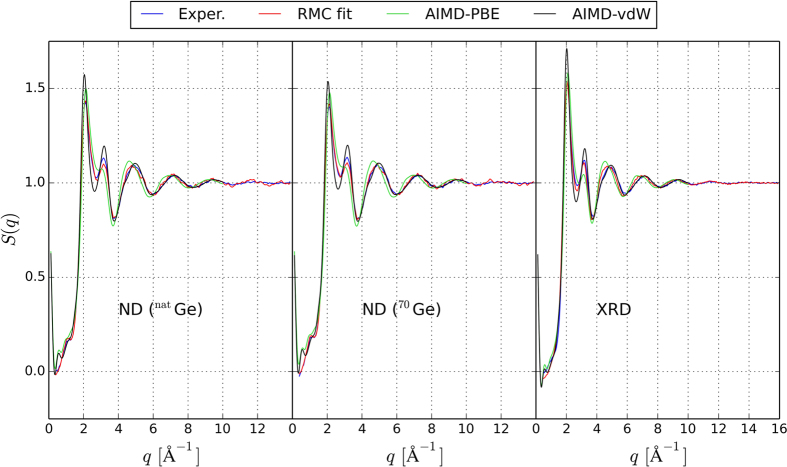

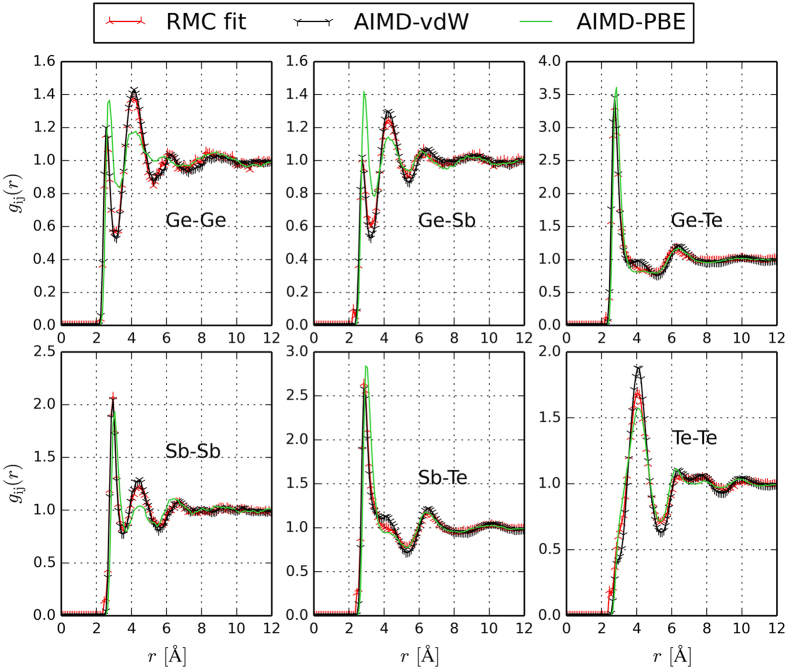

The experimental neutron and X-ray total structure factors S(q) for liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 measured at 923 K (which is close to the melting point, T = 900 K) are compared with AIMD and RMC structure factors in Fig. 1. As the AIMD models are more informative than the RMC configurations, the former are discussed in detail in the following. The AIMD models contain 540 atoms and their density is set to 0.030 Å−3, which is an average over the values we determined experimentally by a high energy γ-ray attenuation method in the temperature range considered (see Table 1). To generate the models, we employ the following procedure: we start from a random configuration and equilibrate the system at T = 3000 K for 30 ps. Then, we quench the system to the target temperature (925 K) and equilibrate for 30 ps. After equilibration, we compute the total partial distribution function g(r), as well as the six partial pair distribution functions gij(r) (where i and j indicate the atomic species) by averaging over 20 ps. The AIMD partial gij(r)’s are plotted in Fig. 2, together with the RMC fits. For the sake of comparison, we also perform AIMD simulations using a standard GGA functional and include the data in Figs 1 and 2. Notice that the three experimental data sets are not sufficient to separate the 6 partial correlation functions of this 3 component system. We calculate the neutron and X-ray structure factor S(q) by combining the partial structure factors Sij(q) (obtained from the Fourier transforms of the gij(r) functions) with the X-ray and neutron diffraction weights. Similar to the experimental structure factors, the AIMD total S(q) curves exhibit a pronounced first peak and a smaller second peak. This is indicative of octahedral order, as discussed in ref. 21, where ND measurements were performed on several GST liquid alloys and compared with other octahedral liquids, as well as with selected tetrahedral liquids. For this purpose, the order parameter S ≡ S(q2)/S(q1) was introduced, where q1 and q2 denote the position of the first and second peak21. Our AIMD models yield S = 0.69. The intensity of the first and second peak of the theoretical S(q) is overestimated as compared to experiments. We also observe a small shift of the peaks to lower values of q. As far as the third and subsequent peaks are concerned, the agreement is excellent. Overall, the curves are closer to experimental values than those obtained using GGA functionals (except for the height of the first peak), which lead to an underestimation of the second peak and a pronounced shift of the third peak to lower diffraction vectors. Notice that there is very good correspondence of the RMC fits with the experimental datasets.

Figure 1. X-ray and neutron diffraction total structure factors S(q) for liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 measured at 923 K (blue curves) compared to the structure factors obtained from vdW-DF2 and GGA AIMD simulations at 925–926 K (black and green curves respectively) and RMC simulations (red curves).

The AIMD S(q) are computed from the partial structure factors Sij(q) weighted by the X-ray or neutron atomic form factors. The partial factors Sij(q) are calculated by Fourier transforming the partial pair correlation functions (shown in Fig. 2).

Table 1. Experimental values of the molar volume and number density of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 as a function of temperature.

| T [K] | V [cm3/mol] | ρ [nm−3] | T [K] | V [cm3/mol] | ρ [nm−3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 893 | 19.582 | 3.075 | 1113 | 19.942 | 3.020 |

| 913 | 19.607 | 3.071 | 1133 | 19.977 | 3.014 |

| 933 | 19.632 | 3.067 | 1153 | 20.016 | 3.009 |

| 953 | 19.660 | 3.063 | 1173 | 20.057 | 3.002 |

| 973 | 19.683 | 3.060 | 1193 | 20.106 | 2.995 |

| 993 | 19.714 | 3.055 | 1213 | 20.154 | 2.988 |

| 1013 | 19.751 | 3.049 | 1233 | 20.190 | 2.983 |

| 1033 | 19.784 | 3.044 | 1253 | 20.242 | 2.975 |

| 1053 | 19.815 | 3.039 | 1273 | 20.292 | 2.968 |

| 1073 | 19.851 | 3.034 | 1293 | 20.337 | 2.961 |

| 1093 | 19.893 | 3.027 |

The experimental uncertainty is less than 0.5%57.

Figure 2. RMC (T = 923 K), vdW-DF2 AIMD (T = 925 K) and GGA AIMD (T = 926 K) partial pair distribution functions gij(r) for liquid Ge2Sb2Te5.

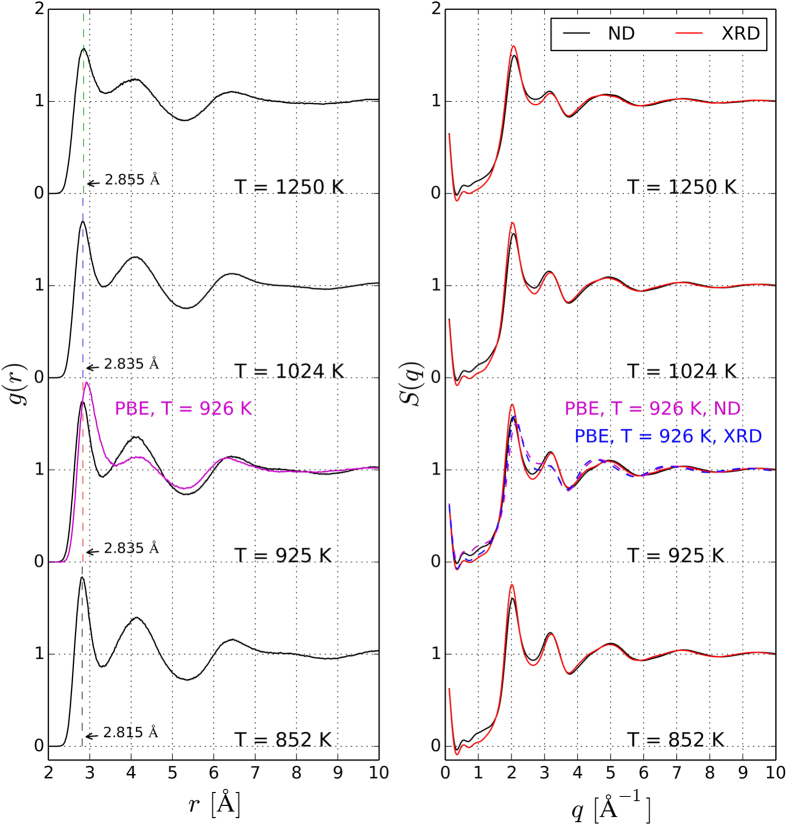

We also perform AIMD simulations at three other temperatures, namely at T = 852, 1024 and 1250 K. Since the melting temperature of Ge2Sb2Te5 is about 900 K, the lowest temperature considered corresponds to a slightly supercooled liquid phase. The total pair distribution functions g(r) are presented in Fig. 3, together with the structure factors, whereas the partial gij(r)’s at 852, 1024 and 1250 K are shown in the supplement, Figs S1–3. We also include the GGA curves at T = 926 K. The latter are in very good agreement with those of ref. 20. Due to the use of the vdW-DF2 functional, which yields a better description of dispersive interactions, the g(r) functions exhibit more pronounced secondary peaks and deeper minima than those obtained from standard GGA calculations. In particular, the second peak at 4.055 Å and the first and second minima at 3.325 and 5.275 Å are better defined, indicating better resolved atomic connectivities and neighbour shells. Moreover, there is a shift of the first peak to smaller interatomic distances – 2.835 Å at 925K (vdW-DF2 simulations), to be compared with 2.92 Å (GGA simulations) – which partially cures the tendency of GGA functionals to yield too long first-neighbour distances for amorphous and liquid PCMs. In refs 27,28, van der Waals semi-empirical corrections40 to GGA functionals were shown to have similar effects on liquid GeTe4 and supercooled liquid Ge2Sb2Te5.

Figure 3. Total radial distribution functions g(r) (left panel) and total structure factors S(q) (right panel) of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 obtained from AIMD simulations.

Temperatures range from 852 K up to 1250 K. The corresponding partial pair correlation functions gij(r) are shown in Fig. 2 (T = 923 K) and in the supplement (T = 852, 1024 and 1250 K). Solid red lines are drawn for the X-ray diffraction structure factors, whereas the S(q) for neutron diffraction are indicated by black lines. In the left panel, vertical dashed lines indicate the position of the first maximum of the vdW-DF2 g(r), underlining the shift to larger particle-particle distances with increasing temperature. GGA AIMD data at T = 926 K are also included. In ref. 27, GGA functionals with van der Waals semi-empirical corrections were employed and a first-peak position of 2.79 Å was obtained for supercooled liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 at T = 820 K.

We evaluate the average coordination number (CN) for each atomic species by integrating the corresponding partial distribution function up to the first minimum (see Table 2). The total and partial CNs increase with temperature. We observe a significant number of Ge-Ge and Ge-Sb bonds, as evidenced by the corresponding partial CNs included in Table 2. Recently, some of us have explained the presence of Ge-Ge bonds in the liquid phase of the parent compound GeTe as due to the small heat of formation of this compound41. These very bonds turn out to be responsible for the presence of tetrahedral structures in rapidly quenched amorphous GeTe41,42. We expect that similar behaviour occurs for Ge2Sb2Te5. Te-Te bonds are also present in the liquid state but their number decreases more drastically upon quenching to the amorphous state14,15. If one compares our CNs for Ge2Sb2Te5 with previous results in the literature, one observes deviations from the values at T = 900 K provided in ref. 20. These discrepancies stem from the use of different functionals and the different cut-off distances employed. There are also some deviations between our data at T = 852 K and the CNs at T = 822 K provided in ref. 28, which indicate that the Grimme corrections give a larger fraction of Ge-Ge and Ge-Sb bonds than vdW-DF2 functionals.

Table 2. Total (Ntot) and partial (NGe, NSb, NTe) coordination numbers in liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 at different temperatures, extracted from the vdW-DF2 AIMD trajectories.

| Temperature | Species | Ntot | NGe | NSb | NTe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = 852 K | Ge | 4.33 | 0.31 (3.16) | 0.45 (3.26) | 3.57 (3.50) |

| Sb | 4.13 | 0.45 (3.26) | 0.59 (3.48) | 3.09 (3.50) | |

| Te | 3.49 | 1.43 (3.50) | 1.23 (3.50) | 0.83 (3.50) | |

| T = 925 K | Ge | 4.32 | 0.36 (3.05) | 0.37 (3.24) | 3.59 (3.50) |

| Sb | 4.17 | 0.37 (3.24) | 0.86 (3.50) | 2.94 (3.50) | |

| Te | 3.57 | 1.43 (3.50) | 1.18 (3.50) | 0.96 (3.50) | |

| T = 1024 K | Ge | 4.36 | 0.33 (3.05) | 0.48 (3.30) | 3.55 (3.50) |

| Sb | 4.23 | 0.48 (3.30) | 0.82 (3.50) | 2.93 (3.50) | |

| Te | 3.66 | 1.42 (3.50) | 1.17 (3.50) | 1.06 (3.50) | |

| T = 1250 K | Ge | 4.50 | 0.44 (3.13) | 0.67 (3.35) | 3.38 (3.50) |

| Sb | 4.33 | 0.67 (3.35) | 0.84 (3.50) | 2.82 (3.50) | |

| Te | 3.78 | 1.35 (3.50) | 1.13 (3.50) | 1.30 (3.50) |

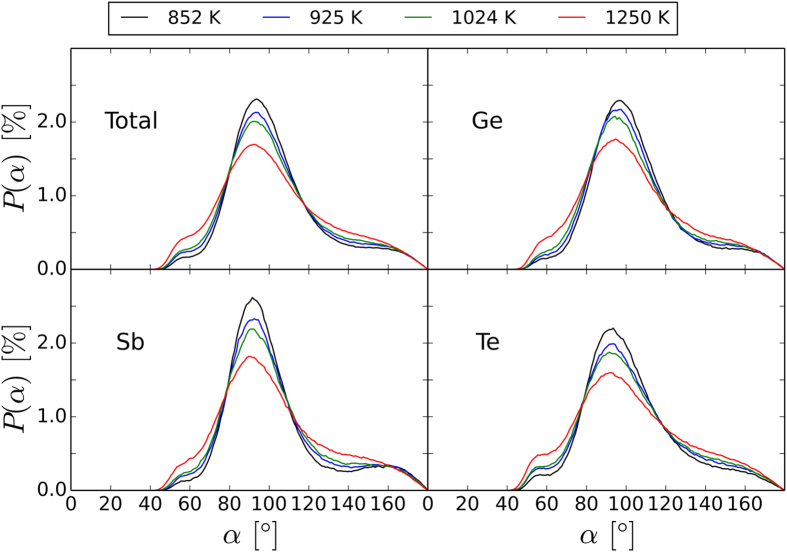

We also compute the bond angle distributions (BADs) (shown in Fig. 4) and the angular-limited three-body correlations (ALTBCs) from the AIMD trajectories (see Fig. 5). We consider both total BADs and partial BADs resolved for different central atoms. All of the total distribution functions display a peak centered at 90°, which is indicative of predominant (defective) octahedral coordination. The height of the peak decreases with increasing temperature. At the same time, the probability of observing bond angles below 80° and above 110° becomes more significant. The partial BADs for central Te are similar to the total ones, whereas the Sb BADs display a narrower main peak. On the other hand, the main peak of the Ge BADs is shifted to larger angles, especially at lower temperatures. This shift is due to the presence of a fraction of Ge atoms with tetrahedral coordination, characterized by bond angles around 104°. These structures contain at least one Ge-Ge or Ge-Sb bond. In fact, the BADs resolved over different atomic sequences shown in the supplement (Figs S4–7) clearly indicate that all the sequences containing Ge-Ge or Ge-Sb are peaked at angles around 105°–110°.

Figure 4. Normalized total BADs and BADs resolved over different central atoms obtained from the vdW-DF2 AIMD simulations for temperatures between 850 K and 1250 K.

As temperature rises, the Ge-, Sb-, and Te-centered distributions broaden to a similar extent. Furthermore, the main peak of the Ge-resolved BADs shifts towards 90°. For an overview of the contributions to the BADs from different bond pairs, see Figs S4–7.

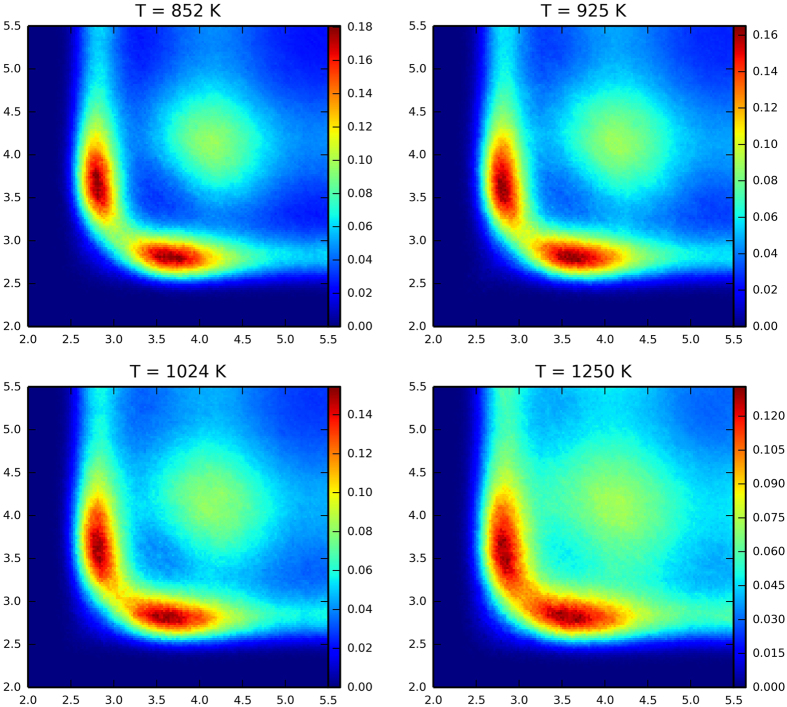

Figure 5. Total angular-limited three-body correlation (ALTBC) of Ge2Sb2Te5 at temperatures T = 852 K, 925 K, 1024 K, and 1250 K, obtained from the vdW-DF2 AIMD simulations.

At the lowest temperature considered, two well-defined peaks indicative of Peierls distortion are observed. At higher temperature, the distortion becomes less pronounced. In particular, at T = 1250 K, the two peaks start to merge.

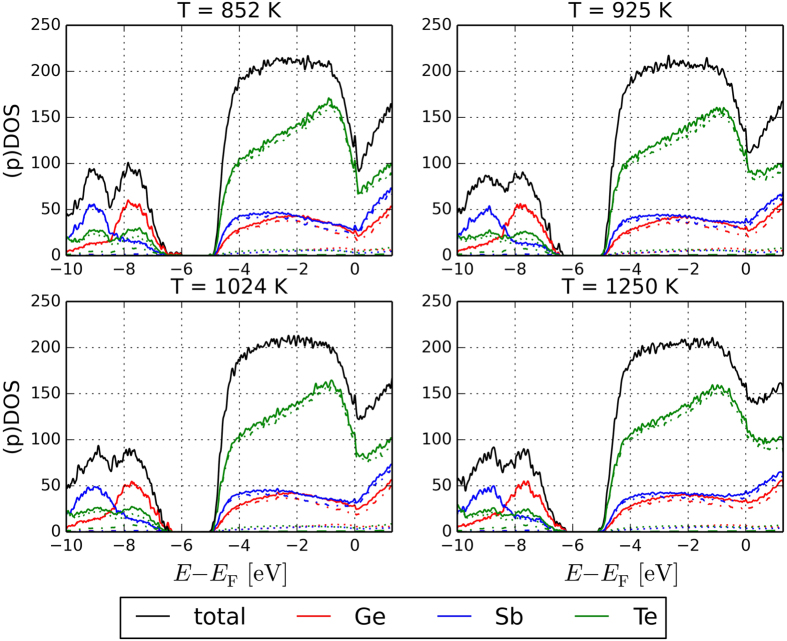

The ALTBC expresses the probability of having a bond of a given length r1 almost aligned with a bond of length r2. We include angular deviations smaller than 25° in the calculation of the probability. The ALTBC distributions exhibit two peaks corresponding to alternating short and long bonds, indicative of Peierls distortion. Interestingly, the distortion appears to decrease upon increasing temperature. More specifically, the height of the two peaks decreases, as well as the distance between them. Partial ALTBC plots are shown in Figs S8–12. Similar effects have been previously observed in liquid GeTe and have been ascribed to the progressive transition from a semiconducting to a metallic liquid43. To further elucidate this phenomenon, we calculate the electronic density of states (averaged over 10 time steps) at different temperatures. This quantity indeed shows a pseudogap at the Fermi energy at low temperatures, whereas, at higher temperatures, the dip tends to disappear (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Electronic density of states (DOS) of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 at different temperatures extracted from the vdW-DF2 AIMD simulations.

The DOS projected (pDOS) onto the (s), (p) and (d) orbitals (dotted, dashed-dotted and dashed lines respectively) of the 3 atomic species is also included. The plots show that the DOS near the Fermi energy EF has predominant (p) character, whereas the (s) orbitals mostly contribute to the states below −6 eV (notice that, in this region, the total DOS of Ge and Sb atoms basically coincides with the pDOS onto the (s) states).

Finally, we compute the primitive ring statistics, which provides information about the intermediate range order. The relevant histograms are shown in Figs S13 and S14. We have calculated the number of rings both for fixed cutoff (3.2 Å) and by employing the cutoffs determined from the partial distribution functions included in Table 2. The most common ring structure is the 5-membered ring, as already discussed in ref. 28 for the supercooled liquid state. This is particularly evident if a fixed cutoff is used. In amorphous GST, 4-membered rings are instead predominant14,15,16. However, 4-membered rings become more numerous at the highest temperature considered (1250 K). Large rings up to 12-membered rings are abundant as well. Overall, an increase in the number of short and long rings is observed with increasing temperature, but only if variable cutoff lengths are used. We also consider ABAB rings, where A stands for Ge or Sb atoms and B denotes Te atoms. In amorphous GST, these rings constitute the majority of 4-membered rings. In our models of the liquid state, the fraction of 4-membered ABAB rings oscillates around 15–25% (using variable cutoffs) and 10–15% (for fixed cutoff).

Kinetic properties

The diffusion coefficients are computed by applying Einstein’s formula,

|

where 〈r2(t)〉 is the mean-squared distance over which the atoms have moved in the time interval t. The latter quantity is calculated by averaging over time and particles. The viscosity η is obtained from the diffusion coefficients using the Stokes-Einstein relation,

|

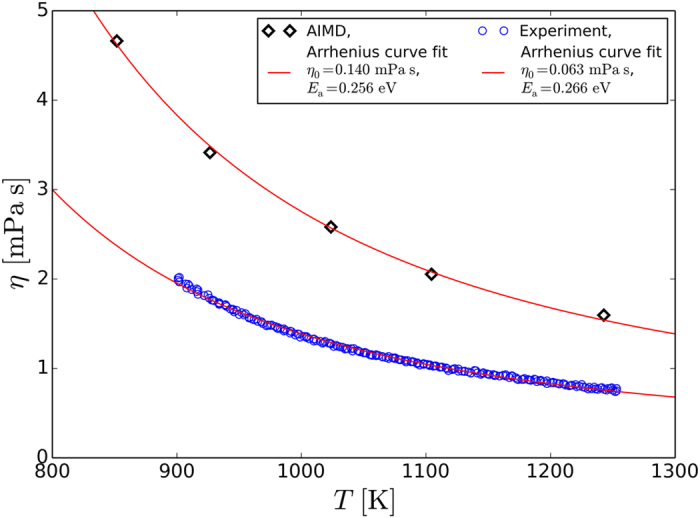

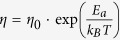

where Rhyd is the hydrodynamic radius. We estimate Rhyd from the simulations of GeTe carried out in ref. 31. We expect that Rhyd for Ge2Sb2Te5 should not differ significantly from the GeTe value. Notice that the Stokes-Einstein relation may break down at low temperatures close to the glass transition temperature due to the high fragility of the supercooled liquid state of GeTe and Ge2Sb2Te529,31. Nonetheless, the relation is definitely valid in the weakly supercooled regime and above the melting temperature. In the temperature interval considered, the viscosities range from 1.6 mPa s to 4.8 mPa s. These values are larger than the experimental viscosities we have measured by the method of oscillating cup, as shown in Fig. 7 (see also Table S1 for the experimental data and Figs S15–19 for the mean-squared displacement plots). The latter quantities vary between 0.8 and 2.0 mPa s in the temperature range between 901 K and 1253 K. In the next section, we discuss possible origins of the mismatch. Nonetheless, we point out that the experimental and theoretical activation energies Ea are very similar. Fitting the two data sets with the Arrhenius equation  , where η0 is a constant representing the asymptotic viscosity at infinite temperature, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature, one obtains η0 = 0.140 mPa s, Ea = 0.256 eV (simulations) and η0 = 0.063 mPa s, Ea = 0.266 eV (experiments). The fit quality of R2 = 0.99205 for the experimental data (R2 = 0.98963 for fit of the AIMD results) shows that the Arrhenius law describes the temperature dependence of the dynamic viscosity for liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 very well.

, where η0 is a constant representing the asymptotic viscosity at infinite temperature, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature, one obtains η0 = 0.140 mPa s, Ea = 0.256 eV (simulations) and η0 = 0.063 mPa s, Ea = 0.266 eV (experiments). The fit quality of R2 = 0.99205 for the experimental data (R2 = 0.98963 for fit of the AIMD results) shows that the Arrhenius law describes the temperature dependence of the dynamic viscosity for liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 very well.

Figure 7. Dynamic viscosity η of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 measured experimentally (blue circles) and calculated from the diffusivity derived from the vdW-DF2 AIMD trajectories by applying Stokes-Einstein relation (black diamonds).

The lines are the fits with the Arrhenius equation  . For the theoretical viscosity, one obtains η0 = 0.140 mPa s, Ea = 0.256 eV; fitting of the experimental data instead yields η0 = 0.063 mPa s and Ea = 0.266 eV.

. For the theoretical viscosity, one obtains η0 = 0.140 mPa s, Ea = 0.256 eV; fitting of the experimental data instead yields η0 = 0.063 mPa s and Ea = 0.266 eV.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, we have determined the structural and dynamic properties of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 in the temperature range between and 850 K and 1250 K. For this purpose, we have performed AIMD and RMC simulations, as well as neutron and X-ray diffraction, oscillating-cup viscometer and γ-ray attenuation experiments. In our AIMD simulations, we have mainly employed the vdW-DF2 functional39, which includes non-local correlations and, thus, provides a better description of van der Waals interactions than standard local and semi-local functionals. In ref. 41 vdW-DF2 simulations were shown to yield accurate models of amorphous GeTe. Our work indicates that this functional is also suitable to describe the liquid state of PCMs. Recently, semi-empirical van der Waals corrections40 in combination with gradient-corrected functionals have been employed to investigate liquid27 and amorphous44 GeTe4, as well as selected Ge-Sb-Te liquids with high Te content28. These corrections have also been shown to improve the level of agreement between calculations and experiments for said chalcogenides, although, for amorphous GeTe, their inclusion appears to be less effective41. Qualitatively speaking, both semi-empirical and ab initio van der Waals functionals lead to more sharply defined atomic connectivities and neighbour shells.

As far as the dynamical properties are concerned, there is qualitative, but not quantitative, agreement between simulations and experiments, in that the experimental viscosities are smaller than the theoretical ones in the temperature range considered. An important source of discrepancy probably lies in the approximations inherent in the exchange-correlation functional employed. In principle, even small deviations between the experimental and computational energy barriers for migration, Ea, can lead to large deviations in the diffusion coefficients and viscosities. Our results indicate that the two activation energies differ by less than 5%. Interestingly, there are large differences in the prefactors η0: the theoretical estimate is more than twice as large as the experimental one. Nevertheless, we should point out that the theoretical Ea and η0 are affected by significant statistical uncertainties because of the small number of data points. It is not obvious what the effect of non-local functionals or Grimme corrections on the kinetic properties should be. In fact, for liquid GeTe4, the latter corrections yield smaller diffusion coefficients and, thus, larger viscosities than plain GGA simulations27. This point deserves further investigation. Another source of error is the finite size effects due to the periodic boundary conditions. These effects originate from the fact that a diffusing particle sets up a slowly decaying hydrodynamic flow, which, in a periodic system, brings about an interference between the particle and its periodic images45. Consequently, one obtains smaller diffusion coefficients as compared to the “real” values corresponding to the thermodynamic limit. Hence, larger simulation cells are expected to reduce the discrepancy with experiments. A third error source is caused by the use of thermostats. This technical point is discussed in the Methods section.

Importantly, the small (high-temperature) activation energy for viscosity we have obtained, Ea = 0.256 eV, is in agreement with previous results about similar phase-change materials29,30,31. Notice that, at lower temperatures, in the deep supercooled regime, there is a dramatic change in the activation energy. This behaviour is due to the high fragility29 of Ge2Sb2Te5 and is ultimately responsible for the remarkable stability of the amorphous state at room temperature a crucial property for applications of PCMs in memory devices.

Methods

Ab-initio molecular dynamics simulations

The AIMD constant-volume (NVT) simulations are carried out with the QUICKSTEP code included in the CP2K package46. We use the very efficient AIMD method developed by Kühne et al.47 This method is intrinsically dissipative and is employed in combination with Langevin thermostats, so that the simulations sample the canonical ensemble47,48. Notice that, in general, stochastic thermostats can affect the dynamical properties of the system significantly. CP2K uses a mixed Gaussian and plane-wave basis set. In our simulations, Kohn-Sham orbitals are expanded in a Gaussian-type basis set of triple-zeta plus polarization quality, whereas the charge density is expanded in plane waves, with a cutoff of 300 Ry. Scalar-relativistic Goedecker49 pseudopotentials are used. The Brillouin zone is sampled at the Γ point.

Reverse Monte-Carlo simulations

Reverse Monte Carlo simulation is performed using rmc++ code50. The simulation box consists of 20250 atoms. Starting atomic configuration is a random distribution of atoms with the following minimum interatomic distance allowed in the model: 2.1 Å for Ge-Ge, 2.2 Å for Ge-Te and Ge-Sb, 2.4 Å for Sb-Sb, Te-Te, and Sb-Te. The atoms are moved randomly to optimize the fit to the experimental XRD and ND structure factors and to all of six partial pair distribution functions obtained by AIMD simulations.

Samples preparation

The Ge2Sb2Te5 master alloys are prepared from proper quantities of pure elements (all 99.999%). An alloy for isotopic substitution neutron diffraction is prepared from 70Ge (enrichment 96.5%) and natural Sb and Te. Because of the high vapour pressure of Sb and Te, the alloys are synthesized in closed quartz ampoules. The ampoules are previously evacuated and filled with Ar to a pressure of about 250 mbar at room temperature. The alloys are melted and homogenized by isothermal heating at 1073 for 5 hours.

X-ray diffraction experiment

X-ray diffraction experiment is carried out at the BW5 experimental station51 at the DORIS synchrotron storage ring, DESY, Hamburg, Germany. The sample is filled and sealed into a thin-walled quartz glass capillary (diameter −2 mm, wall thickness–about 0.02 mm). The sample is heated by a halogen spot-light heater. The energy of the X-ray radiation is 123.5 keV. The size of the incident beam is 1 × 4 mm2. Raw data is corrected for detector dead-time, background, polarization, absorption, variations in detector solid angle, and incoherent scattering. The corrected intensity is normalized to a Faber-Ziman52 total structure factor using X-ray atomic form factors given by Waasmaier and Kirfel53.

Neutron diffraction with isotopic substitution

Neutron diffraction measurements are carried out at the Near and InterMediate Range Order Diffractometer54 (NIMROD) at the ISIS Second Target Station Facility of the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Oxford, UK. The samples are sealed under vacuum in quartz-glass tubes (4.95 mm outer diameter and 0.38 mm wall thickness) made for nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Hilgenberg GmbH, Malsfeld, Germany). The quartz-glass tube with the sample is inserted in a vanadium cylindrical cell (diameter of 6 mm; wall thickness of 40 μm), which is then placed in the middle of a vertical resistance-heating furnace. The sample temperature is kept constant with an accuracy of ±1 K during the isothermal measurements. The beam size is 8 × 30 mm2. Time-of-flight data are collected over a range of diffraction vector q between 0.1 and 30 Å−1. However, the useful range of q is limited to about 15 Å−1 because of the neutron absorption resonances in the sample occurring at high energies. ND measurements are also performed for the empty quartz-glass tube, the empty furnace, the empty spectrometer and the 6 mm thick vanadium rod for the purpose of instrument calibration and data normalization. Raw data are treated using the Gudrun program55 based upon algorithms in the ATLAS package56.

Density measurements

The density of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 alloy is determined by a high energy γ-ray attenuation method. About 110 Mbq of 137Cs is used as a γ-ray source of 662 keV and a NaI scintillation counter is used as a γ-ray detector. Ge2Sb2Te5 specimen is sealed in an ampoule made of fused quartz with a diameter of 1.1 cm and a length of 2.388 ± 0.002 cm. The length of the ampoule is determined by measuring the linear attenuation coefficient of Hg at room temperature. The linear attenuation coefficients for pure elements are measured using freshly powdered specimens compressed into a cylindrical steel tube. They are 0.007005 ± 0.000004 (m2/kg) for Ge, 0.007329 ± 0.000008 (m2/kg) for Sb and 0.007182 ± 0.000003 (m2/kg) for Te. The uncertainty of the experimental values associated with counting statistics is less than 0.11%. The total experimental uncertainty is estimated to be less than 0.5%57.

Viscosity measurements

The dynamic viscosity of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 alloy is measured using an oscillating-cup viscometer described elsewhere58. The sample is sealed in a quartz crucible with 22.5 mm inner diameter under Ar atmosphere as above. The ampoule is inserted into a graphite holder connected to a torsion wire. The oscillating unit is situated in a high-vacuum chamber with a Mo-wire resistance heater and appropriate shielding. The temperature of the sample is measured with uncertainty of about ±5 K by a thermocouple placed at the bottom of the sample holder. The damped torsion oscillations excited by a PC-controlled mechanical unit are detected by means of a laser-beam/photodiode unit. The system is heated at a rate of 5 K min−1 to 1253 K, held for 1 hour at the constant temperature for homogenization, and cooled at a rate of 1 K min−1. Ten to twelve oscillations are registered for each measured point during cooling of liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 alloy down to a solidification point at 900 K. The dynamic viscosity of the melt is determined from the measured oscillations using an equation given by Roscoe et al.59 and modified by Brooks et al.60. The relative uncertainty of the dynamic viscosity is less than 10%, as estimated by Gruner et al.58. The measurements repeated several times showed a very good reproducibility.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Schumacher, M. et al. Structural, electronic and kinetic properties of the phase-change material Ge2Sb2Te5 in the liquid state. Sci. Rep. 6, 27434; doi: 10.1038/srep27434 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to W. Zhang for useful discussions. This work has been financially supported by the German Research Foundation DFG (Contracts Nos Ka-3209/6-1 and Ma-5339/2-1). We also acknowledge the computational resources granted by JARA-HPC from RWTH Aachen University under project JARA0089, as well as funding by the DFG within the collaborative research centre SFB 917 “Nanoswitches”. P. Jóvári was supported by NKFIH (National Research, Development and Innovation Office) Grant No. SNN 116198. Part of this research was carried out at the light source DORIS III at DESY, Hamburg, a member of the Helmholtz Association (HGF). The experiments at the ISIS Pulsed Neutron and Muon Source were supported by a beamtime allocation from the Science and Technology Facilities Council (experiment RB1610107, DOI: 10.5286/ISIS.E.79111252). We thank T. F. Headen, P. McIntyre and A. Sears for support during neutron diffraction experiments.

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.S. performed the AIMD modeling. P.J. and H.W. carried out the RMC simulations. H.W., P.J., T.G.A.Y. and I.K. performed the diffraction and oscillating-cup experiments, whereas Y.T. performed the density measurements. Analysis of the data was carried out by all the authors. The paper was written by R.M. and I.K. with contribution of all coauthors. The project was initiated by R.M. and I.K.

References

- Wuttig M. & Yamada N. Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage. Nat Mater 6, 824–832 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoux S., Welnic W. & Ielmini D. Phase change materials and their application to nonvolatile memories. Chem Rev 110, 240–267 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. et al. Density-functional theory guided advances in phase-change materials and memories. MRS Bulletin 40, 856–865 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Ovshinsky S. Reversible electrical switching phenomena in disordered structures. Phys Rev Lett 21, 1450–1453 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- Yamada N. et al. High speed overwritable phase change optical disk material. Jpn J Appl Phys 26, 61–66 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka T. et al. Crystal structure of GeTe and Ge2Sb2Te5 meta-stable phase. Thin Solid Films 370, 258 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga T. & Yamada N. Structural investigation of GeSb2Te4: A high-speed phase-change material. Phys Rev B 69, 104111 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Wuttig M. et al. The role of vacancies and local distortions in the design of new phase-change materials. Nat Mater 6, 122–128 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolobov A. V. et al. Understanding the phase-change mechanism of rewritable optical media. Nat Mater 3, 703–708 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohara S. et al. Structural basis for the fast phase change of Ge2Sb2Te5: Ring statistics analogy between the crystal and amorphous states. Appl Phys Lett 89, 201910 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Akola J. et al. Experimentally constrained density-functional calculations of the amorphous structure of the prototypical phase-change material Ge2Sb2Te5. Phys Rev B 80, 020201 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Jóvári P. et al. ‘Wrong bonds’ in sputtered amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5. J Phys: Condens Matter 19, 335212 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jóvári P. et al. Local order in amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 and GeSb2Te4. Phys Rev B 77, 035202 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Caravati S., Bernasconi M., Kühne T. D., Krack M. & Parrinello M. Coexistence of tetrahedral- and octahedral-like sites in amorphous phase change materials. Appl Phys Lett 91, 171906 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Akola J. & Jones R. O. Structural phase transitions on the nanoscale: The crucial pattern in the phase-change materials Ge2Sb2Te5 and GeTe. Phys Rev B 76, 235201 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Hegedüs J. & Elliott S. R. Microscopic origin of the fast crystallization ability of Ge–Sb–Te phase-change memory materials. Nat Mater 7, 399–405 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarello R., Caravati S., Angioletti-Uberti S., Bernasconi M. & Parrinello M. Signature of tetrahedral Ge in the Raman spectrum of amorphous phase-change materials. Phys Rev Lett 104, 085503 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welnic W. et al. Unravelling the interplay of local structure and physical properties in phase-change materials. Nature Mater 5, 56–62 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. et al. Local structure of liquid Ge1Sb2Te4 for rewritable data storage use. J Phys: Condens Matter 20, 205102 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akola J. & Jones R. O. Density functional study of amorphous, liquid and crystalline Ge2Sb2Te5: homopolar bonds and/or AB alternation? J Phys: Condens Matter 20, 465103 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimer C. et al. Characteristic ordering in liquid phase-change materials. Adv Mater 20, 4535–4540 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Delheusy M. et al. Structure of liquid Te-based alloys used in rewritable DVDs. Physica B: Condens Matter 350, E1055–E1057 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Kolobov A. V. et al. Liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 studied by extended x-ray absorption. Appl Phys Lett 95, 241902 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Bichara C., Johnson M. & Gaspard J. P. Octahedral structure of liquid GeSb2Te4 alloy: First-principles molecular dynamics study. Phys Rev B 75, 060201 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Caravati S., Bernasconi M. & Parrinello M. First-principles study of liquid and amorphous Sb2Te3. Phys Rev B 81, 014201 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Otjacques C. et al. Dynamics of the negative thermal expansion in tellurium based liquid alloys. Phys Rev Lett 103, 245901 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micoulaut M. Van der Waals corrections for an improved structural description of telluride based materials. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 061103 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ruiz H. et al. Effect of tellurium concentration on the structural and vibrational properties of phase-change Ge-Sb-Te liquids. Phys Rev B 92, 134205 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Orava J., Greer A. L., Gholipour B., Hewak D. W. & Smith C. E. Characterization of supercooled liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 and its crystallization by ultrafast-heating calorimetry. Nat Mater 11, 279–283 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinga M. et al. Measurement of crystal growth velocity in a melt-quenched phase-change material. Nat Commun 4, 2371 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosso G. C., Behler J. & Bernasconi M. Breakdown of Stokes-Einstein relation in the supercooled liquid state of phase change materials. Phys Stat Sol (b) 249, 1880–1885 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. et al. M. How fragility makes phase-change data storage robust: insights from ab initio simulations. Sci Rep 4, 6529 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaban I. et al. Structural studies on Te-rich Ge-Te melts. J Phys Condens Matter 18, 2749 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Kaban I., Jóvári P., Hoyer W. & Welter E. Determination of partial pair distribution functions in amorphous Ge15Te85 by simultaneous RMC simulation of diffraction and EXAFS data. J Non-Cryst Solids 353, 2474–2478 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Kaban I., Jóvári P. & Petkova T. Structure of GeSe4-In and GeSe5-In glasses. J Phys Condens Matter 22, 404205 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rátkai L. et al. Microscopic origin of demixing in Ge20SexTe80−x alloys. J Alloy Comp 509, 5190–5194 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Chrissanthopoulos A. et al. Structure of AgI-doped Ge–In–S glasses: Experiment, reverse Monte Carlo modelling, and density functional calculations. J Solid State Chem 192, 7–15 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- McGreevy R. L. & Pusztai L. Reverse Monte Carlo simulation: A new technique for the determination of disordered structures. Mol Simulat 1, 359–367 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Murray E. D., Kong L., Lundqvist B. I. & Langreth D. C. Higher-accuracy van der Waals density functional. Phys Rev B 82, 081101 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J Comput Chem 27, 1787–1799 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raty J.-Y. et al. Aging mechanisms in amorphous phase-change materials. Nat Commun 6, 7467 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deringer V. L. et al. Bonding nature of local structural motifs in amorphous GeTe. Angew Chem Int Ed 53, 10817–10820 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raty J.-Y. et al. Evidence of a reentrant Peierls distortion in liquid GeTe. Phys Rev Lett 85, 1950 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzid A. et al. Role of the van der Waals interactions and impact of the exchange-correlation functional in determining the structure of glassy GeTe4. Phys Rev B 82, 134208 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Yeh I.-C. & Hummer G. System-size dependence of diffusion coefficients and viscosities from molecular dynamics simulations with periodic boundary conditions. J Phys Chem B 108, 15873–15879 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- VandeVondele J. et al. Quickstep: Fast and accurate density functional calculations using a mixed Gaussian and plane waves approach. Comput Phys Comm 167, 103–128 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Kühne T., Krack M., Mohamed F. R. & Parrinello M. Efficient and accurate Car-Parrinello-like approach to Born-Oppenheimer molecular dynamics. Phys Rev Lett 98, 066401 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühne T., Krack M. & Parrinello M. Static and dynamical properties of liquid water from first principles by a novel Car-Parrinello like approach. J Chem Theory Comp 5, 235–241 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedecker S., Teter M. & Hutter J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys Rev B 54, 1703–1710 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereben O., Jóvári P., Temleitner L. & Pusztai L. A new version of the RMC++ Reverse Monte Carlo programme, aimed at investigating the structure of covalent glasses. J. Optoelectron. Adv. M. 9, 3021–3027 (2007); Code and executables are available at http://www.szfki.hu/~nphys/rmc++/opening.html. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen H. F., Neuefind J., Neumann H.-B., Schneider J. R. & Zeidler M. D. Amorphous silica studied by high energy X-ray diffraction. J Non-Cryst Solids 188, 63–74 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Faber T. E. & Ziman J. M. A theory of the electrical properties of liquid metals. III. The resistivity of binary alloys. Philos Mag 11, 153–173 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- Waasmaier D. & Kirfel A. New analytical scattering-factor functions for free atoms and ions. Acta Crystallogr A 51, 416–431 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Bowron D. T. et al. NIMROD: The Near and InterMediate Range Order Diffractometer of the ISIS second target station. Rev Sci Instrum 81, 033905 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper A. K., Gudrun N. & Gudrun, X. Programs for correcting raw neutron and X-ray diffraction data to differential scattering cross section. Rutherford Appleton Laboratory Technical Report, RAL-TR-2011-013, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hannon A. C., Howells W. S. & Soper A. K. ATLAS: A suite of programs for the analysis of time-of-flight neutron diffraction data from liquid and amorphous samples. Inst Phys Conf Ser 107, 193–211 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Tscuchiya Y. Molar volume and thermodynamics of the structural change of liquid Se-Te system. J Phys Soc Jpn 57, 3851–3857 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Gruner S. & Hoyer W. A statistical approach to estimate the experimental uncertainty of viscosity data obtained by the oscillation cup technique. J. Alloy Comp. 480, 629–633 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe R. & Bainbridge W. Viscosity determination by the oscillating vessel method I: theoretical considerations. Proc Phys Soc 72, 576–584 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R. F., Dinsdale A. T. & Quested P. N. The measurement of viscosity of alloys-a review of methods, data and models. Meas Sci Technol 16, 354–362 (2005). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.