Abstract

Alpha-tocopherol is one the most abundant and biologically active isoforms of vitamin E. This compound is a potent antioxidant and one of most studied isoforms of vitamin E. Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is an important nutrient for calcium homeostasis and bone health, that has also been recognized as a potent modulator of the immune response. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is the most important causative agent of both nosocomial and community-acquired infections. The aim of this study was to evaluate the inhibitory effect of alpha-tocopherol and cholecalciferol on both S. aureus and multidrug resistant S. aureus efflux pumps. The RN4220 strain has the plasmid pUL5054 that is the carrier of gene that encodes the macrolide resistance protein (an efflux pump) MsrA; the IS-58 strain possesses the TetK tetracycline efflux protein in its genome and the 1199B strain resists to hydrophilic fluoroquinolones via a NorA-mediated mechanism. The antibacterial activity was evaluated by determining the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and a possible inhibition of efflux pumps was associated to a reduction of the MIC. In this work we observed that in the presence of the treatments there was a decrease in the MIC for the RN4220 and IS-58 strains, suggesting that the substances presented an inhibitory effect on the efflux pumps of these strains. Significant efforts have been done to identify efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) from natural sources and, therefore, the antibacterial properties of cholecalciferol and alpha-tocopherol might be attributed to a direct effect on the bacterial cell depending on their amphipathic structure.

Keywords: alpha-tocopherol, cholecalciferol, efflux pumps, Staphylococcus aureus

Introduction

Alpha-tocopherol is one of the most abundant and biologically active isoforms of vitamin E. This compound is a potent antioxidant and one of most studied isoforms of vitamin E (Márquez et al., 2002[31]; Catania et al., 2009[7]).Vitamin E is a liposoluble substance that is able to slow aging and protect organisms from non-transmissible chronic diseases, such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, infectious and rheumatic states, cancer and cardiovascular diseases (Catania et al., 2009[7]; Batista et al., 2007[3]; Berg, 2010[4]). Recent findings demonstrated that vitamin E is able to inhibit the growth of malignant cells (Sampaio and Almeida, 2009[44]) and modulate cell signaling and gene transcription (Batista et al., 2007[3]). Vitamin E (Alpha-tocopherol) is naturally present in many products of both plant and animal origin, such as: vegetable oils, wheat germ, oily seeds, dark-red vegetables, egg yolk and in the liver.

Vitamin D3, or cholecalciferol, and vitamin D2, or ergocalciferol, are two different forms of vitamin D obtained by humans. Ergocalciferol is produced by many plants, yeasts and fungi when they are exposed to UVB radiation and cholecalciferol is synthesized in the skin by exposure to UVB radiation (Bikle, 2009[5]). Vitamin D has been recognized as a potent modulator of the immune response and as an important nutrient for calcium homeostasis (Holick, 2004[24]; Heaney, 2005[22]; Miller and Gallo, 2010[34]). The main circulating form of this vitamin in the organism is the 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) (calcidiol), which requires activation by the renal 1 α-hydroxylase to form the metabolically active 1,25-dihydroxvitamin D (1,25[OH]2D) (calcitriol) (DeLuca, 2004[13]).

Liposoluble compounds are known as modifiers of the bacterial cell membrane permeability (Pretto et al., 2004[40]; Nicolson et al., 1999[37]). Therefore, alpha-tocopherol and cholecalciferol due to their liposolubility might increase the permeability of the bacterial cell membrane to various substances, including antibiotics (Andrade et al., 2014[2]).

Beyond the intrinsic resistance properties to certain antibiotics, bacteria can also acquire resistance to antibiotics via horizontal gene transfer and mutations in chromosomal genes. The intrinsic resistance of a bacterial species to a particular antibiotic is its ability to resist to the action of this antibiotic as a result of inherent structural or functional characteristics, resulting on antibiotic inactivation (Blair et al., 2015[6]). Accordingly, there has been increasing concern about bacterial resistance to antibiotics, specially because of the availability and inappropriate use of these drugs (Neuhauser et al., 2003[36]; Sahm et al., 2001[42]). In fact, numerous bacterial strains, especially the methicillin-resistant variety, rapidly became resistant to antibacterial agents after the introduction of antibiotics for treatment of serious infections caused by S. aureus (Harnett et al., 1991[20]; Mesak and Davies, 2009[33]).

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is the most important causative agent of both community-acquired and nosocomial bacterial infections. S. aureus cause these infections through various virulence factors (Costa et al., 2011[10]; Havaei et al., 2010[21]). MRSA strains present resistance to many antibacterial agents, limiting the treatment of many patients infected with these bacteria (Kurlenda and Grinholc, 2012[26]). There are three different mechanisms of antibiotic resistance to S. aureus: inactivation of the antibiotic by hydrolysis or chemical modification; modification of the antibiotic target by genetic mutation or post-translational mechanisms; and reduction of the intracellular concentrations of the antibiotic as a result of deficient penetration into the bacterium or antibiotic efflux by active mechanisms (Blair et al., 2015[6]).

The active efflux of substances that inhibit bacterial growth such as toxic compounds and antibiotics, in S. aureus, is mediated by integral membrane transporters, known as drug efflux pumps (Levy, 1992[27]). There are several categories of active drug efflux pumps that transport drugs against their concentration gradients across the membrane (Levy, 1992[27]). In the S. aureus species, the following efflux proteins are found: QacA (Small multidrug resistance protein from the SMR family) (Paulsen et al., 1996[38]; Saier et al., 1994[43]), Smr (SMR family) (Grinius et al., 1992[19]), Tetk (Major facilitator superfamily from the MFS family), NorA (MFS family) (Yoshida et al., 1990[49]) and MsrA (MFS family) (Reynolds et al., 2003[41]).

Several studies have demonstrated the development of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria during the course of antibiotic treatment which involved efflux pumps (Levy, 2005[29]; Neu, 1992[35]; Levy, 2002[28]). Therefore, it is hypothesized that the antibiotic therapy can be effective if: (i) efflux pumps are inhibited, (ii) the expression of efflux pumps is downregulated, or (iii) the antibiotics are redesigned, so that they are no longer suitable to efflux substrates and thus, their clinical efficacy is restored (Kourtesi et al., 2013[25]).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the inhibitory effect of alpha-tocopherol and cholecalciferol on the Staphylococcus aureus efflux pumps.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains

The following strains of S. aureus were used: RN4220, which has the plasmid pUL5054 that is the carrier of gene that encodes the macrolide resistance protein (an efflux pump) MsrA; IS-58, which possesses the TetK tetracycline efflux protein in its genome and 1199B, which resists to hydrophilic fluoroquinolones via a NorA-mediated mechanism. All strains used in this work were kindly provided by Prof. S. Gibbons (University of London). These strains were maintained in blood agar base culture medium slants (Laboratorios Difco Ltda., Brazil) and, before the assays, the cells were kept grown overnight at 37 °C in Heart Infusion Agar culture medium slants (HIA, Difco) during 24 hours.

Drugs

The antibiotics were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then, diluted in sterile water to the concentration of 1024 μg/mL). Erythromycin, norfloxacin and tetracycline were used as antibiotics. Alpha-tocopherol and cholecalciferol were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, USA). Stock solutions of the vitamins were prepared in 1 mL of DMSO to obtain the concentration of 200 mg/ml and then, this solutions were diluted to 1024 µg/mL in distilled water to reduce the DMSO toxicity.

Antibacterial activity test by Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The MICs of alpha-tocopherol and cholecalciferol were determined in a microdilution assay utilizing an inoculum of 100 μL of each strain suspended in saline solution at 0.5 of the McFarland scale, was added in brain heart infusion (BHI) in Eppendorfs. Then, each sample was transferred to 96-well microtiter plates and serial dilutions of each substance were performed with concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 512 µg/mL. The plates were incubated at 37 °C during 24 h, and bacterial growth was determined using the sodium Resazurin colorimetric method. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration in which no bacterial growth was observed, according to CLSI (2013[9]). The antibacterial assays were performed in triplicate and the results were expressed as average of the replicates.

Evaluation of the inhibition of efflux pumps by reduction of MIC

To analyze whether alpha-tocopherol and cholecalciferol might affect the efflux pump activity, we evaluated the potential of these substances to decrease the MIC of the antibiotics. The inhibition of the efflux pump was evaluated using sub-inhibitory concentrations of alpha-tocopherol and cholecalciferol (MIC/8). A 100 μL sample of a solution containing inoculums, suspended in saline solution at 0.5 of the McFarland scale was added in brain heart infusion (BHI) in Eppendorfs. Then, each sample was transferred to 96-well microtiter plates and serial dilutions of each substance were performed with concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 512 µg/mL. The plates were incubated at 37 °C during 24 h, and bacterial growth was determined using the sodium Resazurin colorimetric method. The antibiotic MICs were used as controls. The antibacterial assays were performed in triplicate and the results were expressed as average of the replicates.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were made in triplicate. The data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and the Tukey´s post test using GraphPad Prism software 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The values are expressed as geometric means and the differences with p ˂ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and Discussion

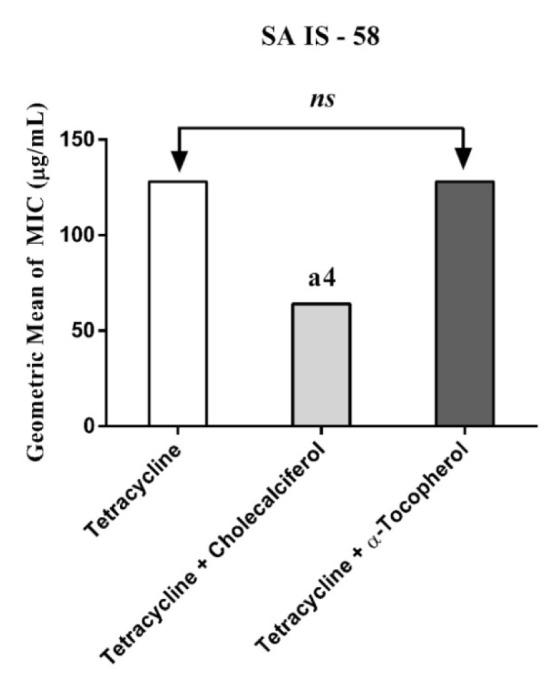

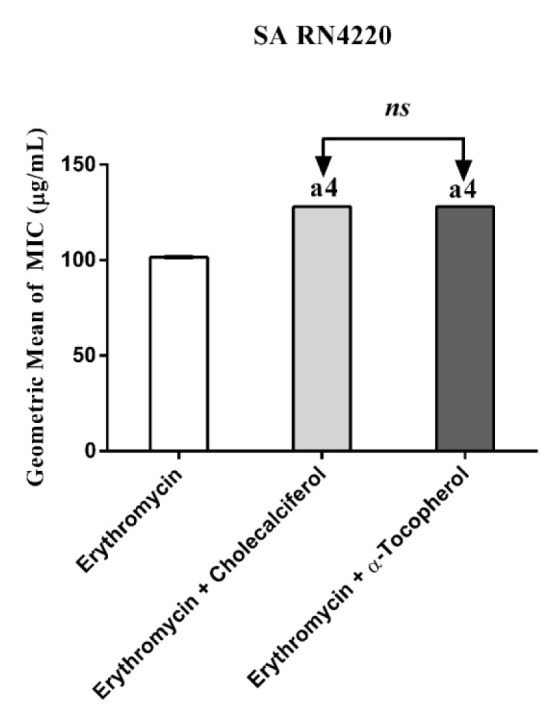

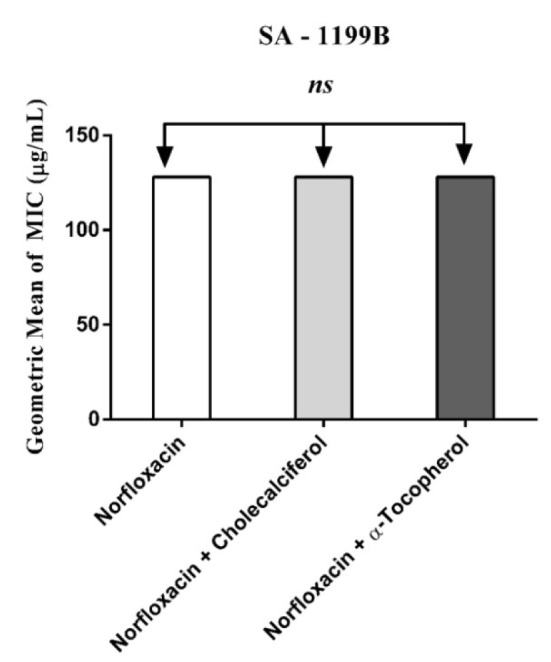

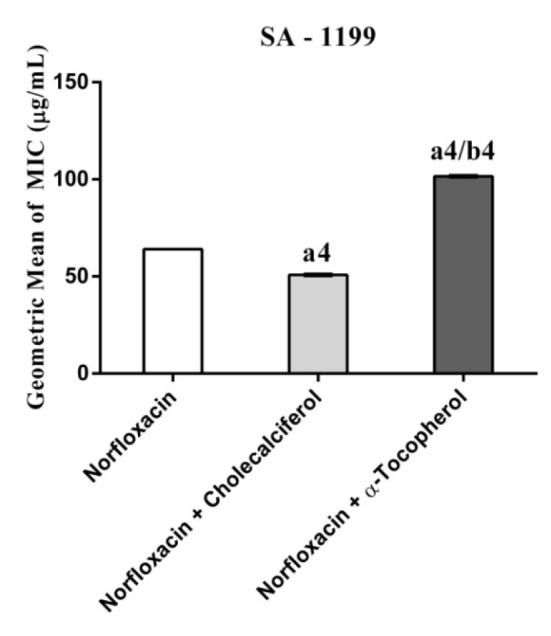

Cholecalciferal and alpha-tocopherol presented a MIC ≥ 1024 µg/mL and, as such, they do not exhibit clinically relevant antibacterial activity. However, when associated with antibiotics against resistant strains carrying efflux pumps, cholecalciferol reduced the MIC values of the antibiotics (Figures 1-4(Fig. 1)(Fig. 2)(Fig. 3)(Fig. 4)).

Figure 1. MIC of Tetracycline alone and in association with the standard vitamins against the strain S. aureus IS-58, expressing the efflux system TetK. One Way ANOVA, followed by the test Tukey. a4p < 0,0001 vs Tetracycline; ns - not significant.

Figure 2. MIC of Erythromycin alone and in association with the standard vitamins against the strain S. aureus RN4220, expressing the efflux system TetK. One Way ANOVA, followed by the test Tukey. a4p < 0,0001 vs Erythromycin; ns - not significant.

Figure 3. MIC of Norfloxacin alone and in association with the standard vitamins against the strain S. aureus 1199B, expressing the efflux system TetK. One Way ANOVA, followed by the test Tukey. ns - not significant.

Figure 4. MIC of Norfloxacin alone and in association with the standard vitamins against the strain S. aureus 1199B wild, expressing the efflux system TetK. One Way ANOVA, followed by the test Tukey. a4p < 0,0001 vs Norfloxacin; b4p < 0,0001 vs Norfloxacin.

Substances that reverse bacterial resistance when associated with antibiotics by reducing their MIC are defined as "modifiers of the antibiotic activity", which can alter the bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics by inhibiting microbial efflux pumps (Costa et al., 2008[11]). Thus, if a substance causes a reduction in the MIC ≥ 3 dilutions when combined with the inhibitor, this is an indicative that this substance affects the bacterial resistance by inhibiting the efflux pump activity (Davies and Wright, 1997[12]).

The association of antibiotics with liposoluble vitamins is an interesting alternative to enhance the antimicrobial efficacy of these drugs, because these vitamins are commonly present in the human feed and present no significant toxicity when used at low concentrations (DiPalma and Ritchie, 1977[14]). This is the first study demonstrating the effect of cholecalciferol and alpha-tocopherol as inhibitors of antibiotic efflux systems. Andrade et al. (2014[2]) were the first researchers to demonstrate the antibiotic modulatory activity against aminoglycosides using a multidrug resistant (MDR) strain of Staphylococcus aureus, although several reports previously demonstrated the antibiotic modulator effect of many non-polar compounds against MDR strains.

Falcão-Silva et al. (2009[15]) demonstrated that the amphipathic kaempferol glycoside tiliroside increased the action antibiotics by reducing the concentration needed to inhibit the growth of the RN4220 and IS-58 strains. One of the factors that might be associated to this inhibition is the lipophilicity of the flavon moiety of tiliroside. Lipophilicity is a common feature of several efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs), and this feature, as pointed out by Gibbons (2004[16]), is probably important for EPIs solubility in the bacterial membrane and binding to the efflux pump or efflux pump substrates. Thus, the lipophilicity of a given compound may be determinant on inhibiting the efflux pump in Gram-positive multi-resistant bacteria (Stavri et al., 2007[47]). Accordingly, several reports have demonstrated that lipophilic compounds act as inhibitors of drug efflux pumps in cancer cells (Werle, 2008[48]). Finally, other amphipathic compounds such as piperidine alkaloids (Gibbons, 2005[17]), acylated oligosaccharides from the orizabin series (Pereda-Miranda et al., 2006[39]) and from the murucoidin series, stoloniferin I (Chérigo et al., 2008[8]) and the phenolic diterpene totarol (Smith et al., 2007[46]) have been reported as EPIs against the SA-1199B strain. However, other factors, including special structural features may be crucial for the action of drugs on efflux pump inhibition.

In fact, the lipophilicity of some substances, including alpha-tocopherol and cholecalciferol can alter the structure of the bacterial lipoprotein membrane, resulting on damage to components that are essential for the membrane integrity, and therefore, efflux pumps and other membrane transporters may be significantly affected by these substances (Gibbons, 2004[16]). The membrane potential can also be affected leading to loss of ions, cytochrome C, proteins and radicals and finally, collapse of proton pumps system and decrease in the intracellular ATP (Sikkema et al., 1994[45]; Hirayama et al., 2006[23]).

Although the studies demonstrating the effect of the combination of antibiotics whit cholecalciferol remain to be developed, a recent study demonstrated the effect of this substance as a modulator of the inflammatory response on bovine mammary epithelial cells (Alva-Murillo et al., 2014[1]). Interestingly, prior to the development of the antibiotics, sunlight (a source of vitamin D), cod liver oil, and pharmacologic doses of liposoluble vitamin D were used to treat tuberculosis (Martineau et al., 2007[32]). This type of treatment fell out of favor following the creation of effective antibiotic therapy. However, the interest in using pharmacologic doses of vitamin D increased recently in view of the finding that this vitamin can stimulate innate immune responses to combat several pathogenic infections in vitro. Thus, vitamin D can act as an "antibiotic", in part, by inducing the transcription of human antimicrobial peptide genes (Liu et al., 2006[30]; Gombart et al., 2005[18]; Zasloff, 2006[50]). By this way, the potential use of cholecalciferol in association with antibiotics can represent an important weapon in the war against the MDR bacteria.

Conclusion

Cholecalciferal and alpha-tocopherol presented different patterns of antibiotic modulatory activity. Cholecalciferol presented a significant modulatory effect on the tetracycline activity against the IS-58 S. aureus strain, indicating that this vitamin enhanced the antibiotic activity by affecting the bacterial of efflux systems. Together, our data suggest that the vitamins act through specific mechanisms that are dependent on the bacterial strain and the vitamin molecular structure and therefore, cholecalciferol can be used in the development of new drugs to treat infections caused by S. aureus resistant strains.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alva-Murillo N, Téllez-Pérez AD, Medina-Estrada I, Álvarez-Aguilar C, Ochoa-Zarzosa A, López-Meza JE. Modulation of the inflammatory response of bovine mammary epithelial cells by cholecalciferol (vitamin D) during Staphylococcus aureus internalization. Microb Pathog. 2014;77:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade JC, Morais-Braga MFB, Guedes GM, Tintino SR, Freitas MA, Menezes IR, et al. Enhancement of the antibiotic activity of aminoglycosides by alpha-tocopherol and other cholesterol derivates. Biomed Pharmacol. 2014;68:1065–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batista ES, Costa AGV, Pinheiro-Sant’ana HM. Adição da vitamina E aos alimentos: implicações para os alimentos e para a saúde humana. Rev Nutr. 2007;20:525–535. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg GA. Vitamina E: un tema siempre presente, nunca concluído. Rev Arg Cardiol. 2010;78:391–392. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bikle D. Nonclassic actions of vitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:26–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair JM, Webber MA, Baylay AJ, Ogbolu DO, Piddock LJ. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:42–51. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catania AS, Barros CR, Ferreira SRG. Vitaminas E minerais com propriedades antioxidantes e risco cardiometabólico: controvérsias e perspectivas. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2009;53:550–559. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302009000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chérigo L, Pereda-Miranda R, Fragoso-Serrano M, Jacobo-Herrera N, Kaatz GW, Gibbons S. Inhibitors of bacterial multidrug efflux pumps from the resin glycosides of Ipomoea murucoides. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1037–1045. doi: 10.1021/np800148w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CLSI. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing;23rd Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100-S23. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa SS, Falcão C, Viveiros M, Machado D, Martins M, Melo-Cristino, et al. Exploring the contribution of efflux on the resistance to fluoroquinolones in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11(1):241. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa VCO, Tavares JF, Agra MF, Falcão-silva VS, Facanali R, Vieira MAR, et al. Composição química e modulação da resistência bacteriana a drogas do óleo essencial das folhas de Rollinia leptopetala. R E Fries Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2008;18:245–248. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies J, Wright GD. Bacterial resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:234–240. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1689–1696. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiPalma JR, Ritchie DM. Vitamin toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1977;17:133–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.17.040177.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falcão‐Silva VS, Silva DA, Souza Mde V, Siqueira‐Junior JP. Modulation of drug resistance in Staphylococcus aureus by a kaempferol glycoside from Herissantia tiubae (Malvaceae) Phytother Res. 2009;23:1367–1370. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons S. Anti-staphylococcal plant natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:263–277. doi: 10.1039/b212695h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbons S. Plants as a source of bacterial resistance modulators and anti-infective agents. Phytochem Rev. 2005;4:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3. FASEB J. 2005;19:1067–1077. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3284com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grinius L, Dreguniene G, Goldberg EB, Liao CH, Projan SJ. A staphylococcal multidrug resistance gene product is a member of a new protein family. Plasmid. 1992;27:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(92)90012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harnett N, Brown S, Krishnan C. Emergence of quinolone resistance among clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Ontario, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1911–1913. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havaei SA, Moghadam SO, Pourmand MR. Prevalence of genes encoding bi-component leukocidins among clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Iran J Publ Health. 2010;39:8–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaney RP. The Vitamin D requirement in health and disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirayama KB, Speridião PGL, Fagundes neto U. Ácidos graxos poliinsaturados de cadeia longa. Elect J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr Liver Dis. 2006;10:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1678–1688. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1678S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kourtesi C, Ball AR, Huang YY, Jachak SM, Vera DMA, Khondkar P, et al. Microbial efflux systems and inhibitors: approaches to drug discovery and the challenge of clinical implementation. Open Microbiol J. 2013;7:34–52. doi: 10.2174/1874285801307010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurlenda J, Grinholc M. Alternative therapies in Staphylococcus aureus diseases. Acta Biochim Pol. 2012;59:171–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy SB. Active efflux mechanisms for antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:695–703. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.4.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy SB. Active efflux, a common mechanism for biocide and antibiotic resistance. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92 Suppl:65S–71S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy SB. Antibiotic resistance: the problem intensifies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:1446–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR. et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311(5768):1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Márquez M, Yépez CE, Sútil-naranjo R, Rincon M. Aspectos básicos y determinación de las vitaminas antioxidantes E y A. Invest Clin. 2002;43:191–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martineau AR, Wilkinson KA, Newton SM, Floto RA, Norman AW, Skolimowska, et al. IFN-γ- and TNF-independent vitamin D-inducible human suppression of mycobacteria: the role of cathelicidin LL-37. J Immunol. 2007;178:7190–7198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mesak LR, Davies J. Phenotypic changes in ciprofloxacin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Res Microbiol. 2009;160:785–791. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller J, Gallo RL. Vitamin D and innate immunity. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neu HC. The crisis in antibiotic resistance. Science. 1992;257(5073):1064–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neuhauser MM, Weinstein RA, Rydman R, Danziger LH, Karam G, Quinn JP. Antibiotic resistance among gram-negative bacilli in US intensive care units: implications for fluoroquinolone use. JAMA. 2003;289:885–888. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicolson K, Evans G, Otoole PW. Potentiation of methicillin, activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by diterpenes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;179:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulsen IT, Skurray RA, Tam R, Saier MH, Turner RJ, Weiner JH, et al. The SMR family: a novel family of multidrug efflux proteins involved with the efflux of lipophilic drugs. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1167–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereda-Miranda R, Kaatz GW, Gibbons S. Polyacylated oligosaccharides from medicinal Mexican morning glory species as antibacterials and inhibitors of multidrug resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:406–409. doi: 10.1021/np050227d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pretto JB, Cechinel filho V, Noldin VF, Sartori MRK, Isaias DEB, Bella CAZ. Antimicrobial activity of fractions and compounds from Calophyllum brasiliense (clusiaceae/guttiferae) Z Naturforsch C. 2004;59:657–662. doi: 10.1515/znc-2004-9-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynolds E, Ross JI, Cove JH. Msr(A) and related macrolide/streptogramin resistance determinants: incomplete transporters? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;22:228–236. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(03)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahm DF, Critchley IA, Kelly LJ, Karlowsky JA, Mayfield DC, Thornsberry C. Evaluation of current activities of fluoroquinolones against gramnegative bacilli using centralized in vitro testing and electronic surveillance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:267–274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.267-274.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saier MH, Jr, Tam R, Reizer A, Reizer J. Two novel families of bacterial membrane proteins concerned with nodulation, cell division and transport. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:841–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sampaio LC, Almeida CF. Vitaminas antioxidantes na prevenção do câncer do colo uterino. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2009;55:289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sikkema J, Bont JAM, Poolman B. Interaction of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8022–8026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith ECJ, Kaatz GW, Seo SM, Wareham N, Williamson EM, Gibbons S. The phenolic diterpene totarol inhibits multidrug efflux pump activity in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4480–4483. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00216-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stavri M, Piddock LJV, Gibbons S. Bacterial efflux pump inhibitors from natural sources. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:1247–1260. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Werle M. Natural and synthetic polymers as inhibitors of drug efflux pumps. Pharm Res. 2008;25:500–511. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9347-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura S, Ubukata K, Konno M. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus NorA gene, which confers resistance to quinolones. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6942–6949. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6942-6949.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zasloff M. Fighting infections with vitamin D. Nat Med. 2006;12:388–390. doi: 10.1038/nm0406-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]