Abstract

Pantothenate kinase 2 deficiency (previously known as Hallervorden-Spatz disease) is an unusual metabolic disorder characterized by progressive extrapyramidal dysfunction and dementia. A 27-year-old Caucasian presented with a major depression disorder and social phobia since adolescence. Patient had marked paranoia, auditory hallucinations, extrapyramidal dysfunction, poor memory, and gait abnormality. Laboratory tests including serum copper and ceruloplasmin were all normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination of the brain played an important role in the diagnosis in this patient.

Abbreviations: MRI, (magnetic resonance imaging)

Case report

A 27-year-old Caucasian presented with a major depression disorder and social phobia since adolescence. The patient had marked paranoia, auditory hallucinations, extrapyramidal dysfunction, poor memory, and gait abnormality. Laboratory tests including serum copper and ceruloplasmin were all normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination of the brain played an important role in the diagnosis in this patient.

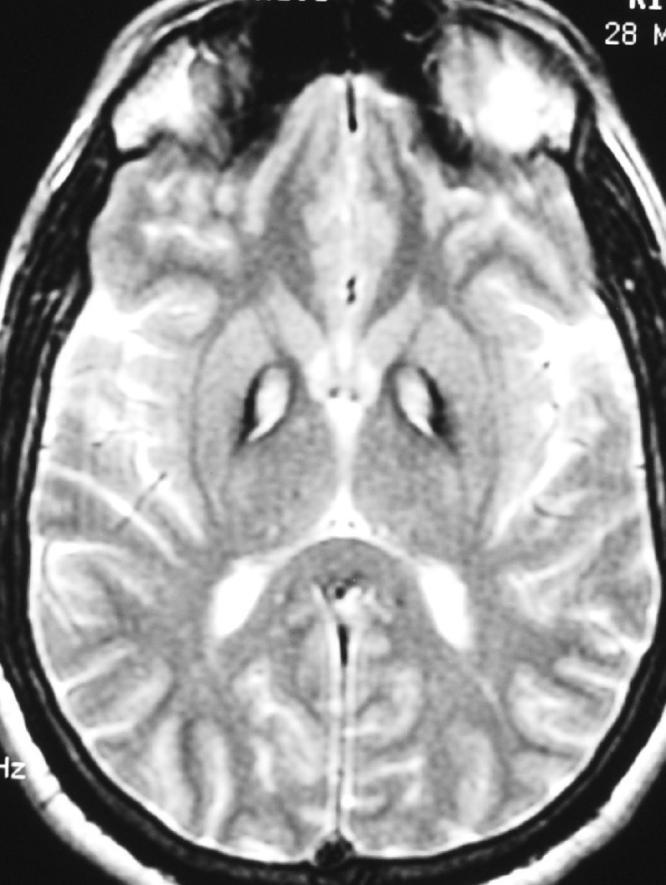

An MRI scan of the brain demonstrated central hyperintensity with surrounding hypointense signal in globus pallidus, bilaterally suggestive of “eye of the tiger” sign on FLAIR (Fig. 1) and T2-weighted (Fig. 2) sequences.

Figure 1.

27-year-old patient with pantothenate kinase 2 deficiency. FLAIR-weighted MRI image shows “eye of tiger” sign with hyperintense center and hypointense periphery in globus pallidus bilaterally.

Figure 2.

27-year-old patient with pantothenate kinase 2 deficiency. T2-weighted MRI image shows “eye of tiger” sign with hyperintense center and hypointense periphery in globus pallidus bilaterally.

Further clinical and laboratory evaluation revealed a low serum pantothenate kinase 2 level, which confirmed the diagnosis of pantothenate kinase 2 defeciency. Subsequent supplementation of pantothenate kinase significantly improved the clinical symptoms.

Discussion

Pantothenate kinase 2 deficiency is an unusual metabolic disorder characterized by progressive extrapyramidal dysfunction, dementia, gait impairment, dystonic posturing, dysarthria, and loss of memory. Onset is most commonly in late childhood or early adolescence, but cases with adult onset have been described. When the disorder is familial, it has autosomal recessive inheritance and has been linked to chromosome 20.

A mutation in the pantothenate kinase (PANK2) gene on band 20p13 has been described in patients with typical pantothenate kinase 2 deficiency (1). It affects both the globus pallidus and the pars reticulata of the substantia nigra in group 1 but involves only the globus pallidus in group II (2). The disease can be familial or sporadic. Brain autopsy demonstrates symmetric bilateral deposition of iron pigment (3). This accounts for the hypointense signal on T2-weighted images. The central hyperintense signal is related to neuronal loss, demyelination, and reactive gliosis.

Disorders of iron metabolism can disrupt cell membranes through lack of antioxidant protection. Nonsense, missense, and frameshift mutations in the pantothenate kinase gene (PANK2) were detected in HSS patients (4). The resulting accumulation of cysteine in the globus pallidus may lead to the chelation and sequestration of iron. Iron plays an important role in the modulation of certain neurotransmitter activities, which are especially associated with dopaminergic mechanisms. The gross brain iron accumulation in HSS and in other neurologic conditions (for example, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease) suggests the possibility that disturbed iron metabolism plays a significant primary or secondary role in the pathogenesis of these conditions, as well as in others in which iron metabolism is disturbed.

The diagnostic criteria (4) continue to evolve to assess the distinctions between PANK and other forms of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). The obligate features have been described as onset during the first two decades of life, progression of signs and symptoms, and evidence of extrapyramidal dysfunction. The corroborative features include corticospinal tract involvement (that is, spasticity and/or extensor toe signs); progressive intellectual impairment; retinitis pigmentosa and/or optic atrophy; seizures; positive family history consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance; hypointense areas on MRI involving the basal ganglia, particularly the substantia nigra; and abnormal cytosomes in circulating lymphocytes and/or sea-blue histiocytes in bone marrow.

The following features exclude the diagnosis of pantothenate kinase 2 deficiency: presence of abnormal ceruloplasmin levels and/or abnormalities in copper metabolism; presence of overt neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis (as demonstrated by severe visual impairment and/or difficult-to-control seizures, often of the generalized type), predominantly epileptic symptoms; severe retinal degeneration or visual impairment preceding other symptoms; presence of familial history of Huntington's chorea and/or other autosomal dominantly inherited neuromovement disorder; presence of caudate atrophy as demonstrated by imaging studies; nonprogressive course; and absence of extrapyramidal signs.

Pantothenate kinase was originally described by Hallervorden and Spatz and is also known as Hallervorden-Spatz disease. However, since Hallervorden and Spatz were closely associated with Nazi extermination policies (5), recently pantothenate kinase 2 deficiency has become the preferred term for this entity.

Footnotes

Published: September 4, 2009

References

- 1.Zhou B, Westaway SK, Levinson B. A novel pantothenate kinase gene (PANK2) is defective in Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;28:345–349. doi: 10.1038/ng572. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayflick SJ, Hartman M, Coryell J. Brain MRI in neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation with and without PANK2 mutations. J Neuroradiol. 2006 Apr;27(6):1230–1233. [PubMed] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raji V, Dhanasegaran SE, Usha Hallervorden Spatz Disease. Journal of the association of physicians of India. 2006 Apr;54:320–322. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swaiman KF. Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome and brain iron metabolism. Arch Neurol. 1991 Dec;48(12):1285–1293. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530240091029. [PubMed] Review. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper PS. Naming of syndromes and unethical activities: the case of Hallervorden and Spatz. Lancet. 1996;348(9036):1224–1225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05222-1. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]