Abstract

End-stage liver disease secondary to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the major indication for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) worldwide. The percentage of HCV patients infected with genotype 4 (G4) among recipients of OLT varies depending on geographic location. In the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, G4 infection is the most common genotype among transplant recipients. Due to the low prevalence of HCV-G4 in Europe and the United States, this genotype has not been adequately studied in prospective trials evaluating treatment outcomes and remains the least studied variant. The aim of this review is to summarize the natural history and treatment outcome of HCV-G4 following liver transplantation, with particular attention to new HCV therapies. This review incorporates all published studies and abstracts including HCV-G4 patients.

Keywords: Cirrhosis, direct antiviral agents, genotype 4, hepatitis C, liver transplantation

Hepatitis C genotype 4 (HCV-G4) is the most prevalent genotype in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia[1,2,3,4,5,6] and Northern Africa[7,8,9,10] [Table 1]. The frequency of infection with HCV-G4 is increasing in European countries, particularly among intravenous drug users.[11,12,13,14] Due to the low prevalence of HCV-G4 in Europe and the United States, this genotype has not been adequately studied in prospective trials evaluating treatment outcomes and remains the least studied variant.

Table 1.

Reported prevalence of various genotypes in Saudi Arabia

The impact of HCV-G4 on treatment outcomes in the general nontransplant population has been studied.[9,10,15,16,17,18] Studies from the Middle East suggest a higher rate of spontaneous resolution after acute HCV-G4 infection.[19,20] Other studies suggest that HCV-G4 infection is associated with significant steatosis. These observations suggest that specific features of HCV-G4 infection may contribute to the natural history and treatment outcomes of the disease.[21,22] End-stage liver disease secondary to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the major indication for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) worldwide.[23] The percentage of HCV-G4 patients among recipients of OLT varies depending on the geographic location. In Saudi Arabia, hepatitis C represents approximately 29% of indications for liver transplantation, approximately 60% of which are secondary to HCV-G4.[24] HCV-G4 represents more than 90% of indications for liver transplantation in Egypt.[25] By contrast, HCV-G4 is a relatively uncommon indication for liver transplantation in the Western world.[26,27] The aim of this review is to examine the natural history and treatment outcomes of HCV-G4 following liver transplantation. This review includes all published studies and abstracts involving HCV-G4 patients.

POST-LIVER TRANSPLANTATION OUTCOME

Several studies have specifically evaluated the impact of different HCV genotypes on the outcome of liver transplantation. Campos-Varela et al. evaluated the role of different HCV genotypes on the progression and outcome of liver transplantation. Among 745 recipients, 81% had genotype 1 (G1), 7% had genotype 2 (G2), and 12% had genotype 3 (G3). Patients were followed for a median of 3.1 years (range 2–8 years). The risk of advanced fibrosis and graft rejection was significantly higher among those infected with G1 compared with other genotypes.[28] Other studies have reported similar poorer outcomes in G1-infected patients.[29,30] By contrast, some large studies have observed no difference in the rate or degree of hepatitis in the graft, or patient survival between G1 and other genotypes.[31,32] Although clearly demonstrating an influence of HCV genotype on post-transplant outcomes, the majority of these studies have neglected HCV-G4 infection.

OVERALL OUTCOME

According to reports from Saudi Arabia and Egypt, which have active liver transplant programs, overall graft and patient survival for HCV-G4 are comparable to rates reported in the international literature. In Saudi Arabia, where three active cadaveric liver transplant programs exist, the overall three-year graft and patient survival rates were approximately 90% and 80%, respectively, with at least 20% of the cases were due to HCV-G4.[24,33,34,35,36,37] Similarly, in Egypt, where many active living–related liver transplant programs exist and HCV-G4 represents more than 90% of cases, graft and patient survival rates were approximately 86%.[25]

In a recent study comparing the outcomes of Saudi and Egyptian patients receiving liver transplantation either in China or locally in Saudi Arabia (approximately 30% of patients were infected with HCV-G4), respective one- and three-year cumulative survival rates were 81% and 59% in patients transplanted in China compared with 90% and 84% for patients transplanted locally. The poorer outcomes in China were attributed to more liberal selection criteria, the use of donations after cardiac death, and possibly more limited post-transplant care.[38]

NATURAL HISTORY OF HCV-G4 AFTER LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Re-infection of the graft with HCV is universal after liver transplantation regardless of genotype, leading to an accelerated course of liver injury in many cases.[39] Most studies of disease recurrence worldwide have investigated HCV-G1, HCV-G2, and HCV-G3,[23] and there are few reports on post-OLT recurrence of HCV-G4.

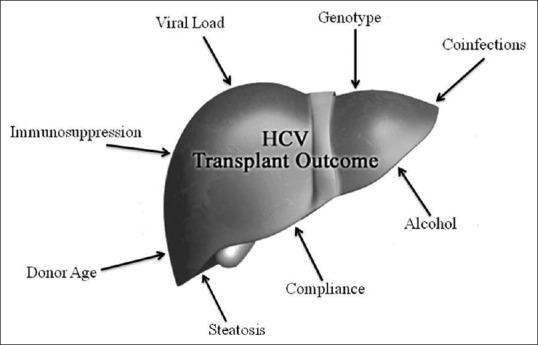

Four studies have been reported from liver transplant centers in Europe and Australia. Gane et al. reported a group of 149 patients who received liver transplants for HCV-related end-stage liver disease and were followed for a median of 36 months. Among the patient population, 14 patients (of whom 12 were from the Middle East) were infected with HCV-G4. Approximately 50% of these patients had progressive liver disease (moderate hepatitis or cirrhosis) during the follow-up period.[40] In the same study, patients infected with G1b had the worst outcome, whereas patients infected with G2 and G3 had less severe disease recurrence. The authors speculated that patients infected with G1b had an increased replicative potential, increased heterogeneity of HCV quasispecies, and increased expression of viral antigen in liver tissue. Alternatively, HCV-1b may be more immunogenic than other genotypes. In another study, Zekry et al. analyzed the entire cohort of HCV transplant recipients in Australia and New Zealand over a span of 10 years. In this analysis, 182 patients were transplanted for HCV (16 of whom had HCV-G4), and the median follow-up was 4 years. Among many factors studied in univariate and multivariate analyses, HCV-G4 was associated with an increased risk of re-transplantation and death. Additionally, patients infected with HCV-G4 were more likely to progress to stage 3 or 4 fibrosis.[41] Patients infected with G2 and G3 had better post-transplant outcomes. Whether this difference in outcomes was related to the pathogenicity of HCV-G4 or to other factors not examined in this study, including donor age, immunosuppression, and compliance with medications, is not clear [Figure 1]. Additionally, patients infected with HCV-G4 in this study were older and more likely to have coexisting hepatocellular carcinoma. Another Australian study demonstrated that G1b was associated with higher recurrence rates after transplantation compared with other genotypes.[42] In a more detailed study from the UK, 32 of 128 patients who underwent OLT for hepatitis C were infected with HCV-G4.[43] A significantly higher fibrosis progression rate was observed in HCV-G4 patients compared with non-G4 patients, although their rates of survival were similar. The five-year cumulative rates for the development of cirrhosis or severe fibrosis were 84% in HCV-G4-infected patients and 24% in patients infected with other genotypes. The authors attributed the difference between these two groups to the significantly older age of donors and ethnic backgrounds of the HCV-G4 group patients (predominantly Egyptian). In addition, the majority of these patients were placed on an alternative waiting list to be offered organs that were suitable for transplantation but unsuitable or not needed for citizens of the United Kingdom. This policy may have led to the selection of inferior grafts for the HCV-G4 patients, who were predominantly non-UK citizens, leading to inferior results in these patients.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting the outcome of HCV-related transplantation

By contrast, studies from the Middle East show a more favorable outcome for HCV-G4 patients. A study on biopsy-proven recurrence of HCV post-OLT in Saudi Arabia revealed no significant differences between G1 and G4 patients in terms of epidemiological, clinical, and histological factors as well as outcome (patients and graft survival).[44] Among many epidemiological, laboratory, and virological factors included in that analysis, the only factor predictive of an advanced histological score was the HCV RNA level at the time of biopsy.

In studies published from Egypt reporting on living-related liver transplantation of HCV-G4 patients, similar favorable outcomes were observed. HCV clinical recurrence was observed in 31% of patients and was mostly mild; 91% of patients had fibrosis scores less than F2. After 36 months of follow-up, 91% of patients were alive with good graft function. Similar to the study from Saudi Arabia, recurrent HCV was associated with a high pre- and post-transplant viral load and the presence of antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen.[45] In another study, the outcome of living-related liver transplantation was evaluated in Egyptian patients with HCV-G4-related cirrhosis. Recipient and graft survivals were 86.6% at the end of the follow-up, comparable to literature reports for deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT). Clinical HCV recurrence was observed in 10/38 patients (26.3%). Four patients developed mild fibrosis, with a mean fibrosis score of 0.6 and a mean histological activity index (HAI) of 7.1. None of the recipients developed allograft cirrhosis during the mean follow-up period of 16 months (range 4–35 months).[25]

The role of HCV-G4 in the natural history of this disease requires further study. Furthermore, HCV-G4 exhibits significant genetic diversity, and there are a number of viral subtypes. HCV-G4 subtypes 4a and 4b predominate in Egypt, whereas subtypes 4c and 4d are the most prevalent in Saudi Arabia.[5] The impacts of the various subtypes have been demonstrated in recent studies; for example, a recent trial in HCV G1 patients determined that subtype 1b patients were more likely to achieve a rapid virological response (RVR) compared with subtype 1a, thereby requiring shorter periods of combination treatment.[46] Studies performed in Egypt, where HCV-G4 subtypes 4a and 4b predominate, have consistently indicated higher rates of virological response to therapy (69%–76%) compared with Saudi Arabia, where response rates are substantially lower (44%–50%).[47,48,49] In a retrospective analysis of HCV-G4 patients, Roulot et al. reported better sustained virological response (SVR) in 4a subtype- compared with 4d subtype-infected individuals.[50] The majority of patients involved in these European/Australian studies are Egyptians, who are likely older, have coexisting HCC and have received marginal donor grafts. Co-morbidities, such as infection with schistosomiasis, and other nonstudied variables may also have affected outcomes in these patients, leading to an impression that HCV-G4 is an aggressive virus. However, more recent studies originating from the Middle East, where HCV-G4 predominates, have revealed no significant difference in outcomes between G1 and G4.

TREATMENT PRIOR TO TRANSPLANTATION

Pegylated interferon and ribavirin

Viral eradication or suppression prior to liver transplantation reduces post-transplant recurrence rates.[51] However, older treatment regimens were interferon-based and were therefore contraindicated in decompensated cirrhosis.[52,53,54]

This approach has been evaluated by multiple groups. Everson et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy and safety of pre-transplant pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin (Peg-IFN-a2b/RBV) for the prevention of post-transplant HCV recurrence. Patients were assigned to a low accelerating dose regimen (LADR) in which they received a combination of Peg-IFN and RBV with increasing dose every two weeks until they reached a maximal tolerated dose. Patients with G1, G4, or G6 were randomized to LADR or no pretransplantation treatment. Of the 30 patients with G1, G4, or G6 who were treated, 23 underwent liver transplantation, and 22% achieved a post-transplantation virological response. Although pre-transplant treatment prevented post-transplant recurrence of HCV infection in 25% of cases, including patients infected with HCV-G4, this approach was poorly tolerated and resulted in life-threatening complications.[55]

TREATMENT OF ADVANCED DISEASE IN THE NEW ERA

The treatment of HCV patients is rapidly evolving. After decades of limited treatment options with low efficacy rates and intolerable side effects, new oral, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents have emerged with better safety and efficacy profiles, leading to dramatic changes in the practice of HCV management. Sofosbuvir (SOF) is a novel pangenotypic nucleotide analog inhibitor that inhibits HCV RNA replication. SOF is administered orally and inhibits the HCV NS5B polymerase. SOF exerts potent antiviral activity against all HCV genotypes with or without Peg-IFN. SOF administered once daily at a dose of 400 mg exhibits a high barrier to resistance.[56] Multiple clinical studies have demonstrated the superiority of SOF-based therapy compared with the current standard of care in both treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients across all HCV genotypes.[57,58,59,60] Because of its favorable pharmacological profile and its reasonable drug–drug interactions, SOF has become a cornerstone of HCV infection management. Data on the use of these new agents in cirrhotic G4 patients awaiting liver transplantation are limited. Up-to-date studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of these agents in HCV-G4 patients are summarized below.

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin

In an open-label study, 61 patients with HCV of any genotype and cirrhosis and who were on waitlists for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma received up to 48 weeks of SOF/RBV before liver transplantation. Of 46 patients, 43 had HCV-RNA levels of less than 25 IU/Ml at the time of transplantation. Of these 43 patients, 30 (70%) exhibited a post-transplantation virological response at 12 weeks.[61] A recently published Egyptian study evaluated the efficacy and safety of SOF in combination with RBV in HCV-G4 patients in Egypt. In that study, 17% of the study population were cirrhotic. Patients with cirrhosis at baseline had lower rates of SVR12 (63% at 12 weeks, 78% at 24 weeks) than those without cirrhosis (80% at 12 weeks, 93% at 24 weeks). However, the treatment was safe and well tolerated, with no serious drug-related adverse events.[62]

Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and ribavirin (SOLAR-1)

A recently published phase 2, open-label study (Solar-1) assessed treatment with the NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir (LDV), the nucleotide polymerase inhibitor SOF, and RBV in patients infected with HCV-G1 or HCV-G4. This study included a cohort of patients with cirrhosis and moderate or severe hepatic impairment who had not undergone liver transplantation, and another cohort of patients who had undergone liver transplantation. In the nontransplant group, SVR12 was achieved in 86%–89% of patients. Furthermore, response rates were similar in the 12- and 24-week groups.[63]

Sofosbuvir+daclatasvir+ribavirin (ALLY-1 study)

The ALLY-1 study evaluated daclatasvir (DCV)+SOF+RBV in patients with advanced cirrhosis or post-transplant HCV recurrence of all genotypes, including G4. DCV is a pangenotypic NS5A inhibitor with a very low potential for drug interaction and a favorable safety profile. All patients with advanced cirrhosis were treated with a combination of DCV 60 mg + S0F 400 mg + RBV (adjusted dose) for 12 weeks. Overall, 83% of the advanced cirrhosis patients achieved SVR12. The response rate of cirrhotic patients infected with HCV-G4 in this study was 100% (4/4). Treatment was well tolerated, with no adverse events or drug–drug interactions.[64]

Simeprevir+daclatasvir+sofosbuvir (phase II IMPACT study)

The interim results of the IMPACT study indicated favorable responses to this combination in cirrhotic patients infected with G1 and G4. Simeprevir (SIM) is a NS3/4A protease inhibitor with antiviral activity against G1, G2, G4, G5, and G6. All cirrhotic patients (100%) 28/28 achieved SVR4. The treatment was safe and well tolerated, with no major adverse effects. The study is ongoing, and final results are awaited.[65]

TREATMENT AFTER LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Multiple studies have evaluated the outcome of early preemptive treatment using pegylated interferon-based therapy prior to established disease recurrence. However, the outcomes of these studies were poor because of poor tolerability, renal impairment, cytopenias, and drug interactions. The conclusion of these studies was that the outcome of preemptive treatment was similar to that of controls in terms of histological recurrence, graft loss, and death.[66,67] However, most of these studies were performed in HCV-G1-infected patients. Data on treating HCV-G4 recurrence following liver transplantation are limited [Table 2].

Table 2.

Studies involving HCV-G4 patients following liver transplantation

Pegylated interferon and ribavirin

Reported SVR rates for pegylated interferon combination therapy following liver transplantation are lower than those in the nontransplant population. Treatment regimens have been hindered by a high incidence of adverse effects, leading to treatment withdrawal.

In a recent study from Saudi Arabia, —25 patients infected with HCV-G4 were treated with Peg-IFN alpha-2a at a dose of 180 µg/week plus RBV 800 mg/day (the dose was adjusted as tolerated in the range of 400–1200 mg).[68] Eighty-eight percent achieved an early virological response; of those, 15 (60%) and 14 (56%) patients achieved end of treatment virological response and SVR, respectively. The relatively high response rate in this study may have been due to the treatment-naïve status of the patients, the use of growth factors that allowed patients to complete their course of therapy, the low treatment–withdrawal rate, and the reduction of immunosuppression doses during treatment.

In a study from Egypt, Dabbous et al. evaluated 243 patients transplanted for HCV-G4-related cirrhosis. All patients had a protocol biopsy six months post-transplant, and follow-up biopsies were performed at 3, 6, and 12 months during treatment for the early detection of immune-mediated rejection induced by interferon. Fifty-six (23%) patients had evidence of histopathological recurrence of HCV, and 42 patients completed the treatment. Five patients were excluded due to fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis; therefore, 37 patients were included in the study. The patients received treatment in the form of combined Peg-IFN and RBV. Erythropoietin and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor were used in 70% of patients. SVR was achieved in 29 (78%) patients. The high SVR rate in this study was attributed to several factors, including the early treatment protocol, exclusion of patients with fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis, early detection of interferon-induced rejection and aggressive treatment of hematological complication using erythropoietin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and, in some cases, blood transfusion.[69] Conversely, Ponziani et al. evaluated treatment responses in 17 Italian patients with HCV-G4 recurrence following liver transplantation. They reported an SVR rate of 35%. However, this retrospective study included patients treated in the 1990s with conventional interferon; the drug tolerability, and the lack of aggressive management of hematological side effects contributed to the low response rate. Furthermore, their patient population included patients with advanced disease.[70]

The results of these studies suggest that post-transplant treatment outcomes for HCV-G4 are likely better than for G1 and less favorable than for G2 and G3. This response pattern among the different genotypes parallels the response pattern in the immunocompetent population. The availability of newer treatment options with better safety profiles is drawing attention away from pegylated interferon and ribavirin. However, a role for these agents remains in combination with DAA, particularly in mild-to-moderate disease.

HCV TREATMENT IN THE NEW ANTIVIRAL ERA

Telaprevir and boceprevir

Following the approval of telaprevir (Incivek™) and boceprevir (Victrelis™) for G1,[78,79] treatment outcomes improved. Treatment regimens for chronic HCV-G1 infection include a combination of either of these protease inhibitors three times daily with once-weekly subcutaneous injections of Peg IFN and twice-daily oral RBV. These new combinations increased SVR to 80% and 63%–66%, respectively, in nontransplant patients. Some studies have reported poor clinical outcomes of the use of telaprevir along RBV and Peg-IFN in patients with HCV-G4.[80] Although the use of these two DAAs in post–liver transplant patients resulted in SVR up to 60% with telaprevir, nonresponders were observed in the boceprevir treatment, and it was associated with severe side effects, including severe anemia that required erythropoietin, ribavirin dose reduction, and red blood cell transfusions. Significant drug interactions also occurred with immunosuppressants, requiring average cyclosporine dose reductions of 50%–84% after telaprevir initiation and 33% after boceprevir initiation. Tacrolimus doses were reduced by 95% with telaprevir.[81] These significant side effects coupled with the introduction of safer antiviral drugs have shifted HCV treatment away from these agents; in fact, these agents are contraindicated by many liver associations.

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin

SOF has become a cornerstone of management of HCV infection because of its favorable pharmacological and drug interaction profiles. However, there are very limited data on the use of SOF in patients with HCV recurrence post–liver transplant, particularly G4. A recent prospective multicenter study enrolled 40 patients with compensated recurrent HCV infection of any genotype after a primary or secondary liver transplantation. All patients received 24 weeks of SOF 400 mg daily and RBV starting at 400 mg daily; RBV was adjusted according to creatinine clearance and hemoglobin values. Of the 40 patients enrolled and treated, 40% had cirrhosis (based on biopsy), and 88% had been previously treated with interferon. SVR12 was achieved by 28 of 40 patients (70%; 90% confidence interval: 56%–82%). Relapse accounted for all cases of virological failure, including the only patient with HCV-G4. No patients had detectable viral resistance during or after treatment. The most common adverse events were fatigue (30%), diarrhea (28%), and headache (25%). In addition, 20% of the subjects experienced anemia. No deaths, graft losses, or episodes of rejection occurred. No interactions with any concomitant immunosuppressive agents were reported.[71] A recent post-transplantation study was conducted in which SOF and RBV were provided on a compassionate-use basis to patients with severe recurrent HCV, including those with fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis (FCH) and decompensated liver cirrhosis with a life expectancy of less than one year. All patients received SOF and RBV for 24–48 weeks. The study population included patients infected with G1, G2, G3, and G4. The overall SVR rate was 59% and was higher (73%) in those with early severe recurrence. At the end of the study, 57% of patients displayed clinical improvement, 22% were unchanged, 3% had worsened clinical status, and 13% had died. Side effects associated with hepatic decompensation were the most frequently reported adverse events in this study.[72] An ongoing study evaluating SOF and RBV with or without Peg-IFN in post-transplant treatment of experienced G4-infected patients revealed positive results. SVR12 was achieved in 20 patients, and four patients relapsed after achieving negative viremia. By week 4, three patients had detectable HCV RNA. One patient had detectable HCV RNA by week 6, and none had viral breakthrough until the end of treatment. Three of the patients who developed a viral relapse had detectable viremia at week 4 (unpublished observation, Alajlan et al.).

Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir with or without ribavirin

Cohort B (of the previously described Solar-1 study) enrolled patients who had undergone liver transplantation, including those without cirrhosis; those with cirrhosis and mild, moderate, or severe hepatic impairment; and those with FCH. Patients were randomly assigned to receive a fixed-dose combination tablet containing LDV and SOF plus RBV for 12 or 24 weeks. The cohort included 108 post-transplant patients. SVR12 was achieved in 96%–98% of patients without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, in 85%–88% of patients with moderate hepatic impairment, in 60%–75% of patients with severe hepatic impairment, and in all six patients with FCH. Response rates were similar in the 12- and 24-week groups.[63] The preliminary results of the prospective Solar-2 trial, which includes post–liver transplant patients infected with G1 and G4, revealed similar results. Overall, 91% (10/11) of noncirrhotic G4 patients treated for 12 weeks achieved SVR12 compared with 100% (7/7) of those treated for 24 weeks. Of those with more severe G4 disease, only 57% (4/7) achieved SVR12 after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 86% (6/7) of those treated for 24 weeks.[73] Despite including G1 and G4 in these studies, the number of HCV-G4-infected patients was relatively small, limiting solid conclusions on the response of G4. Reddy et al. reported preliminary results of a prospective multicenter study evaluating the safety and efficacy of LDV/SOF with RBV in post-transplant naïve and treatment-experienced patients infected with G1 and G4. In total, 223 patients were treated, including 111 patients with cirrhosis, and the majority (83%) were treatment experienced. Patients in this study were treated for 12-24 weeks. Interim analysis revealed SVR4 rates of 96% and 94% for non-cirrhotic patients treated for 12 and 24 weeks, respectively. Respective SVR4 rates in cirrhotic patients were 92% and 82% for those treated for 12 and 24 weeks. Side effects in this study included anemia (6), sick sinus syndrome (1), sinus arrhythmia (1), and portal vein thrombosis (1). Five patients with cirrhosis died during the study period due to disease-related complications.[74] A study from France reported the outcome of a 12-week course of LDV/SOF without RBV in 44 patients infected with G4. Overall, 21/22 (96%) and 20/22 (91%) of treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients, respectively, achieved SVR12. By comparison, 31/34 (96%) and 10/10 (100%) of noncirrhotic and cirrhotic patients, respectively, achieved SVR12.[75]

The safety profile of LVD/SOF with RBV was evaluated in a pooled analysis of two large multicenter studies (Solar-1 and -2). The patients involved were either cirrhotic or post–liver transplantation patients (616 G1 and 42 G4) and were randomized to 12 or 24 weeks of treatment. Of 134 SAEs, only 20 were related to treatment. RBV-associated anemia was the most common adverse effect, representing 11/20 (55%) reported drug-related adverse events.[82]

Sofosbuvir/daclatasvir

Data on the use of DCV in the post-transplant setting for HCV-G4-infected patients are limited. Leroy et al. analyzed data from 23 patients with FCH who participated in a prospective cohort study in France and Belgium to assess the effects of antiviral agents in patients with recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation. Three patients with G4 infection were included in this study (one patient was treated with SOF/RBV, and two were treated with SOF/DCV). All patients survived without re-transplantation. Rapid and dramatic improvements in clinical status were observed. The patients' median bilirubin concentration decreased from 122 µmol/L at baseline to a normal value at week 12 of treatment. Twenty-two patients (96%) had a complete clinical response at week 36, and 22 patients (96%) achieved SVR12, including all three patients infected with G4.[76]

Sofosbuvir and simeprevir

In a recent report, three patients with HCV-G4 recurrence following liver transplantation were treated with SOF and SIM for at least 12 weeks. All three had high pretreatment viral loads, and one patient had established cirrhosis. SVR12 was achieved in all three patients, with no significant adverse effects or drug interactions.[77]

TIMING OF TREATMENT FOR PATIENTS ON THE TRANSPLANT LIST

It is unclear if treatment should be initiated while the patient is awaiting liver transplantation or to delay until after transplantation [Figure 2]. Many factors may contribute to and affect the approach on an individual basis; for example, it may be better to defer treatment in extremely ill patients, in the presence of renal impairment and in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Afdhal et al. evaluated the outcome of treatment with SOF and RBV in compensated and decompensated cirrhotic patients. They also monitored the clinical picture and measured the hepatic venous pressure gradient before and after treatment. They observed a clinically meaningful improvement in portal hypertension in addition to improvements in liver biochemistry, Child–Pugh score and Model For End-Stage liver Disease scores.[83] The potential benefits of treating patients on the waiting list include potential improvements in overall clinical status that may salvage these patients from liver transplantation, particularly in countries with limited liver donation, reducing post-transplant recurrence, and avoiding possible post-transplant drug–drug interactions.[63,73] One concern is that treating these patients may lower their MELD scores and drive them down the transplant list, thus delaying transplantation despite persistent ascites or encephalopathy. The ideal approach will become clearer following the accumulating results of ongoing trials and a better understanding of the safety profiles of these medications, particularly in the post-transplantation setting.

Figure 2.

Natural history of recurrent HCV after liver transplantation and potential treatment strategies for HCV-G4 infection

CONCLUSIONS

HCV-G4 is a common indication for OLT in many Middle Eastern countries. The results of studies of both cadaveric and living-related liver transplantation, including HCV-G4 patients, indicate good long-term results comparable with those of other genotypes. Similarly, based on the limited available evidence, the course of recurrent HCV-G4 after liver transplantation does not appear to differ from that of other genotypes. In the era of DAAs, the outcome of chronic HCV infection, including advanced liver disease, is likely to improve. Additionally, post–liver transplant outcomes will probably improve, but more studies are needed to further understand HCV-G4 and OLT.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, Brown A, Cooke GS, Pybus OG, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61:77–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.27259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Aziz F, Habib M, Mohamed MK, Abdel-Hamid M, Gamil F, Madkour S, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in a community in the Nile Delta: Population description and HCV prevalence. Hepatology. 2000;32:111–5. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.8438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray SC, Arthur RR, Carella A, Bukh J, Thomas DL. Genetic epidemiology of hepatitis C virus throughout Egypt. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:698–707. doi: 10.1086/315786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abozaid SM, Shoukri M, Al-Qahtani A, Al-Ahdal MN. Prevailing genotypes of hepatitis C virus in Saudi Arabia: A systematic analysis of evidence. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33:1–5. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2013.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shobokshi OA, Serebour FE, Skakni L, Al-Saffy YH, Ahdal MN. Hepatitis C genotypes and subtypes in Saudi Arabia. J Med Virol. 1999;58:44–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Traif I, Al Balwi MA, Abdulkarim I, Handoo FA, Alqhamdi HS, Alotaibi M, et al. HCV genotypes among 1013 Saudi nationals: A multicenter study. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33:10–2. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2013.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu LZ, Larzul D, Delaporte E, Bréchot C, Kremsdorf D. Hepatitis C virus genotype 4 is highly prevalent in central Africa (Gabon) J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2393–8. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ndjomou J, Pybus OG, Matz B. Phylogenetic analysis of hepatitis C virus isolates indicates a unique pattern of endemic infection in Cameroon. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2333–41. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlan Y, Ather HM, Al-ahmadi M, Batwa F, Al-hamoudi W. Sustained virological response in a predominantly hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infected population. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4429–33. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al Ashgar H, Helmy A, Khan MQ, Al Kahtani K, Al Quaiz M, Rezeig M, et al. Predictors of sustained virological response to a 48-week course of pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 4. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:4–14. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsoulidou A, Sypsa V, Tassopoulos NC, Boletis J, Karafoulidou A, Ketikoglou I, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in Greece: Temporal trends in HCV genotype-specific incidence and molecular characterization of genotype 4 isolates. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ansaldi F, Bruzzone B, Salamaso S, Rota MC, Durando P, Gasparini R, et al. Different seroprelavence and molecular epidemiology pattern of hepatitis C virus infection in Italy. J Med Virol. 2005;76:327–32. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández-Arcás N, López-Siles J, Trapero S, Ferraro A, Ibáñez A, Orihuela F, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus subtypes 4c and 4d in Malaga (Spain): Phylogenetic and epidemiological analyses. J Med Virol. 2006;78:1429–35. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicot F, Legrand-Abravanel F, Sandres-Saune K, Boulestin A, Dubois M, Alric L, et al. Heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus genotype 4 strains circulating in south-western France. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:107–14. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derbala MF, El Dweik NZ, Al Kaabi SR, Al-Marri AD, Pasic F, Bener AB, et al. Viral kinetic of HCV genotype-4 during pegylated interferon alpha 2a: Ribavirin therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:591–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Khayat HR, Fouad YM, El Amin H, Rizk A. A randomized trial of 24 versus 48 weeks of peginterferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin in Egyptian patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 4 and rapid viral response. Trop Gastroenterol. 2012;33:112–7. doi: 10.7869/tg.2012.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamal SM, El Kamary SS, Shardell MD, Hashem M, Ahmed IN, Muhammadi M, et al. Pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin in patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C: The role of rapid and early virologic response. Hepatology. 2007;46:1732–40. doi: 10.1002/hep.21917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamal SM. Hepatitis C genotype 4 therapy: Increasing options and improving outcomes. Liver Int. 2009;29((Suppl 1)):39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamal SM, Fouly AE, Kamel RR, Hockenjos B, Al Tawil A, Khalifa KE, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b therapy in acute hepatitis C: Impact of onset of therapy on sustained virologic response. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:632–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamal SM, Moustafa KN, Chen J, Fehr J, Abdel Moneim A, Khalifa KE, et al. Duration of peginterferon therapy in acute hepatitis C: A randomized trial. Hepatology. 2006;43:923–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.21197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamal S, Nasser I. Hepatitis C genotype 4: What we know and what we don't yet know. Hepatology. 2008;47:1371–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.22127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AlQaraawi AM, Sanai FM, Al-Husseini H, Albenmousa A, AlSheikh A, Ahmed LR, et al. Prevalence and impact of hepatic steatosis on the response to antiviral therapy in Saudi patients with genotypes 1 and 4 chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1222–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terrault N, Berenguer M. Treating Hepatitis C infection in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1192–204. doi: 10.1002/lt.20865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Sebayel M, Khalaf H, Al-Sofayan M, Al-Saghier M, Abdo A, Al-Bahili H, et al. Experience with 122 consecutive liver transplant procedures at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center. Ann Saudi Med. 2007;27:333–8. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2007.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yosry A, Esmat G, El-Serafy M, Omar A, Doss W, Said M, et al. Outcome of living donor liver transplantation for Egyptian patients with hepatitis c (genotype 4)-related cirrhosis. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1481–4. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rustgi VK. The epidemiology of hepatitis C infection in the United States. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:513–21. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roche B, Samuel D. Risk factors for hepatitis C recurrence after liver transplantation. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14((Suppl 1)):89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campos-Varela I, Lai JC, Verna EC, O'Leary JG, Todd Stravitz R, Forman LM, et al. Consortium to Study Health Outcomes in HCV Liver Transplant Recipients (CRUSH-C).Hepatitis C genotype influences post-liver transplant outcomes. Transplantation. 2015;99:835–40. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Féray C, Caccamo L, Alexander GJ, Ducot B, Gugenheim J, Casanovas T, et al. European collaborative study on factors influencing outcome after liver transplantation for hepatitis C. European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (EUROHEP) Group. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:619–25. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prieto M, Berenguer M, Rayón JM, Córdoba J, Argüello L, Carrasco D, et al. High incidence of allograft cirrhosis in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection following transplantation: Relationship with rejection episodes. Hepatology. 1999;29:250–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou S, Terrault NA, Ferrell L, Hahn JA, Lau JY, Simmonds P, et al. Severity of liver disease in liver transplantation recipients with hepatitis C virus infection: Relationship to genotype and level of viremia. Hepatology. 1996;24:1041–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vargas HE, Laskus T, Wang LF, Radkowski M, Poutous A, Lee R, et al. The influence of hepatitis C virus genotypes on the outcome of liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:22–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.500040103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Sebayel M. Survival after liver transplantation: Experience with 89 cases. Ann Saudi Med. 1999;19:216–8. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1999.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kizilisik TA, al-Sebayel M, Hammad A, al-Traif I, Ramirez CG, Abdulla A. Hepatitis C recurrence in liver transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2875–7. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)00715-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.al Sebayel M, Kizilisik AT, Ramirez C, Altraif I, Hammad AQ, Littlejohn W, et al. Liver transplantation: Experience at King Fahad National Guard Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2870–1. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)00713-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.al Sebayel M. Liver transplantation: Five-year experience in Saudi Arabia. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:3157. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00765-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al Sebayel MS, Ramirez CB, Abou Ella K. Th first 100 liver transplants in Saudi Arabia. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2709. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allam N, Al Saghier M, El Sheikh Y, Al Sofayan M, Khalaf H, Al Sebayel M, et al. Clinical outcomes for Saudi and Egyptian patients receiving deceased donor liver transplantation in China. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1834–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berenguer M, Prieto M, Rayón JM, Mora J, Pastor M, Ortiz V, et al. Natural history of clinically compensated hepatitis C virus-related graft cirrhosis after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2000;32:852–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gane EJ, Portmann BC, Naoumov NV, Smith HM, Underhill JA, Donaldson PT, et al. Long-term outcome of hepatitis C infection after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:815–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zekry A, Whiting P, Crawford DH, Angus PW, Jeffrey GP, Padbury RT, et al. Australian and New Zealand Liver Transplant Clinical Study Group. Liver transplantation for HCV-associated liver cirrhosis: Predictors of outcomes in a population with significant genotype 3 and 4 distribution. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:339–47. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugo H, Balderson GA, Crawford DH, Fawcett J, Lynch SV, Strong RW, et al. The influence of viral genotypes and rejection episodes on the recurrence of hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Surg Today. 2003;33:421–5. doi: 10.1007/s10595-002-2537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wali MH, Heydtmann M, Harrison RF, Gunson BK, Mutimer DJ. Outcome of liver transplantation for patients infected by hepatitis C, including those infected by genotype 4. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:796–804. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mudawi H, Helmy A, Kamel Y, Al Saghier M, Al Sofayan M, Al Sebayel M, et al. Recurrence of hepatitis C virus genotype-4 infection following liver transplantation: Natural history and predictors of outcome. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:91–7. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yosry A, Abdel-Rahman M, Esmat G, El-Serafy M, Omar A, Doss W, et al. Recurrence of hepatitis c virus (genotype 4) infection after living-donor liver transplant in Egyptian patients. Exp Clin Transplant. 2009;7:157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen DM, Morgan TR, Marcellin P, Pockros PJ, Reddy KR, Hadziyannis SJ, et al. Early identification of HCV genotype 1 patients responding to 24 weeks peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kd)/ribavirin therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:954–60. doi: 10.1002/hep.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alfaleh FZ, Hadad Q, Khuroo MS, Aljumah A, Algamedi A, Alashgar H, et al. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Saudi patients commonly infected with genotype 4. Liver Int. 2004;24:568–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khuroo MS, Khuroo MS, Dahab ST. Meta-analysis: A randomized trial of peginterferon plus ribavirin for the initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:931–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kamal SM, El Tawil AA, Nakano T, He Q, Rasenack J, Hakam SA, et al. Peginterferon {alpha}-2b and ribavirin therapy in chronic hepatitis C genotype 4: Impact of treatment duration and viral kinetics on sustained virological response. Gut. 2005;54:858–66. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.057182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roulot D, Bourcier V, Grando V, Deny P, Baazia Y, Fontaine H, et al. Observational VHC4 Study Group. Epidemiological characteristics and response to peginterferon plus ribavirin treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:460–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fortune BE, Martinez-Camacho A, Kreidler S, Gralla J, Everson GT. Post-transplant survival is improved for hepatitis C recipients who are RNA negative at time of liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2015;28:980–9. doi: 10.1111/tri.12568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Everson GT. Treatment of hepatitis C in the patient with decompensated cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3((Suppl 2)):S106–12. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00699-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Everson GT, Trotter J, Forman L, Kugelmas M, Halprin A, Fey B, et al. Treatment of advanced hepatitis C with a low accelerating dosage regimen of antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2005;42:255–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.20793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crippin JS, McCashland T, Terrault N, Sheiner P, Charlton MR. A pilot study of the tolerability and efficacy of antiviral therapy in hepatitis C virus-infected patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:350–5. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.31748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Everson GT, Terrault NA, Lok AS, Rodrigo del R, Brown RS, Jr, Saab S, et al. Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study. A randomized controlled trial of pretransplant antiviral therapy to prevent recurrence of hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2013;57:1752–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.25976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pawlotsky JM. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C: Current and future. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;369:321–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-27340-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH, Ding X, Svarovskaia E, Symonds WT, et al. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:34–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kowdley KV, Lawitz E, Crespo I, Hassanein T, Davis MN, DeMicco M, et al. Sofosbuvir with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for treatment-naive patients with hepatitis C genotype-1 infection (ATOMIC): An open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:2100–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lawitz E, Lalezari JP, Hassanein T, Kowdley KV, Poordad FF, Sheikh AM, et al. Sofosbuvir in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for non-cirrhotic, treatment-naive patients with genotypes 1, 2, and 3 hepatitis C infection: A randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:401–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1878–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Curry MP, Forns X, Chung RT, Terrault NA, Brown R, Jr, Fenkel JM, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin prevent recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation: An open-label study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:100–7.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doss W, Shiha G, Hassany M, Soliman R, Fouad R, Khairy M, et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treating Egyptian patients with hepatitis c genotype 4. J Hepatol. 2015;63:581–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Charlton M, Everson GT, Flamm SL, Kumar P, Landis C, Brown RS, Jr, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of HCV infection in patients with advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:649–59. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poordad F, Schiff ER, Vierling JM, Landis C, Fontana RJ, Yang R, et al. Daclatasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin combination for HCV patients with advanced cirrhosis or post-transplant recurrence: ALLY-1 phase 3 study. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S261. doi: 10.1002/hep.28446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lawitz E, Poordad F, Gutierrez J, Kakuda T, Picchio G, De La Rosa G, et al. LPo7: Simeprevir (SMV) plus daclatasvir (DCV) and sofosbuvir (SOF) in treatment-naïve and -experienced patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 or 4 infection and decompensated liver disease: Interim results from the Phase II IMPACT study. J Hepatol. 2015;62((Suppl 2)):S266–7. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bzowej N, Nelson DR, Terrault NA, Everson GT, Teng LL, Prabhakar A, et al. PHOENIX Study Group. PHOENIX: A randomized controlled trial of peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin as a prophylactic treatment after liver transplantation for hepatitis C virus. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:528–38. doi: 10.1002/lt.22271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chalasani N, Manzarbeitia C, Ferenci P, Vogel W, Fontana RJ, Voigt M, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a for hepatitis C after liver transplantation: Two randomized, controlled trials. Hepatology. 2005;41:289–98. doi: 10.1002/hep.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Al-hamoudi W, Mohamed H, Abaalkhail F, Kamel Y, Al-Masri N, Allam N, et al. Treatment of genotype 4 hepatitis C recurring after liver transplantation using a combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1848–52. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dabbous HM, Elmeteini MS, Sakr MA, Montasser IF, Bahaa M, Abdelaal A, et al. Optimizing outcome of recurrent hepatitis C virus genotype 4 after living donor liver transplantation: Moving forward by looking back. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:822–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.11.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ponziani FR, Milani A, Gasbarrini A, Zaccaria R, Viganò R, Donato MF, et al. Treatment of recurrent genotype 4 hepatitis C after liver transplantation: Early virological response is predictive of sustained virological response. An AISF RECOLT-C group study. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:338–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Charlton M, Gane E, Manns MP, Brown RS, Jr, Curry MP, Kwo PY, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for treatment of compensated recurrent hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:108–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Forns X, Charlton M, Denning J, McHutchison JG, Symonds WT, Brainard D, et al. Sofosbuvir compassionate use program for patients with severe recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2015;61:1485–94. doi: 10.1002/hep.27681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Manns M, Forns X, Samuel D, Denning J, Arterburn S, Brandt-Sarif T, et al. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with ribavirin is safe and efficacious in decompensated and post-liver transplantation patients with HCV infection: Preliminary results of the SOLAR-2 trial. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S187. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reddy KR, Everson GT, Flamm SL, Denning J, Arterburn S, Brandt-Sarif T, et al. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with ribavirin for the treatment of HCV in patients with post transplant recurrence: Preliminary results of a prospective, multicenter study. Hepatology. 2014;60((Suppl 4)):200A. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abergel A, Loustaud-Ratti V, Metivier S, Jiang D, Kersy K, Knox SJ, et al. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for the treatment of patients with chronic genotype 4 or 5 HCV infection. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S219. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leroy V, Dumortier J, Coilly A, Sebagh M, Fougerou-Leurent C, Radenne S, et al. Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA et les Hépatites Virales CO23 Compassionate Use of Protease Inhibitors in Viral C in Liver Transplantation Study Group. Efficacy of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir in patients with fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1993–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.05.030. e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ascha M, Ascha M, Zein NN, Alkhouri N, Eghtesad B, Abu-Elmagd K, et al. Treatment of recurrent hepatitis c genotype-4 post-liver transplantation with sofosbuvir plus simeprevir. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2015;6:86–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, et al. REALIZE Study Team. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Manns MP, Markova AA, Calle Serrano B, Cornberg M. Phase III results of Boceprevir in treatment naïve patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1. Liver Int. 2012;32((Suppl 1)):27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Armignacco O, Andreoni M, Sagnelli E, Puoti M, Bruno R, Gaeta GB, et al. Recommendations for the use of hepatitis C virus protease inhibitors for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in HIV-infected persons. A position paper of the Italian Association for the Study of Infectious and Tropical Disease. New Microbiol. 2014;37:423–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Antonini TM, Furlan V, Teicher E, Haim-Boukobza S, Sebagh M, Coilly A, et al. Therapy with boceprevir or telaprevir in HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infected patients to treat recurrence of hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation. AIDS. 2015;29:53–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Samuel D, Manns M, Forns X, Flamm SL, Reddy KR, Denning J, et al. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with ribavirin is safe in>600 decompensated and post-liver transplantation patients with HCV infection: An integrated safety analysis of the SOLAR-1 and SOLAR-2 trials. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S620. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Afdhal N, Everson GT, Calleja JL, McCaughan G, Bosch J, Denning J, et al. LP13: Effect of long term viral suppression with sofosbuvir+ribavirin on hepatic venous pressure gradient in HCV-infected patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;62((Suppl 2)):S269–70. [Google Scholar]