Abstract

This study examined the effect of message framing on African American women’s intention to participate in health-related research and actual registration in ResearchMatch (RM), a disease-neutral, national volunteer research registry. A community-engaged approach was used involving collaboration between an academic medical center and a volunteer service organization formed by professional women of color. A self-administered survey which contained an embedded message framing manipulation was distributed to over 2,000 African American women attending the 2012 National Assembly of The Links, Incorporated. A total of 391 surveys were completed (187 containing the gain-framed message and 194 containing the loss-framed message). The majority (57%) of women expressed favorable intentions to participate in health-related research, and 21% subsequently enrolled in RM. The effect of message framing on intention was moderated by self-efficacy; there was no effect of message framing on RM registration, however those with high self-efficacy were over two times as likely as those with low self-efficacy to register as a potential study volunteer in RM (OR=2.62; 1.29,5.33). This investigation makes theoretical and practical contributions to the field of health communication and informs future strategies to meaningfully and effectively include women and minorities in health-related research.

Keywords: research participation, message framing, African American, women, research volunteer registries

Introduction

Participation in health-related research by adequate numbers of minorities and women ensures that the following key outcomes are achieved in research: emerging science is relevant to these groups, sex- or group-based differences and their implications can be evaluated, and the distribution of research risks and benefits upholds the ethical principle of justice. Historically, African Americans experienced major barriers towards research participation. These barriers included distrust due to a past history of inappropriate research methods applied specifically to this population (Branson, Davis, & Butler, 2007; Corbie-Smith, Thomas, & St. George, 2002; Heller et al., 2014; Kanarek, Kanarek, Olatoye, & Carducci, 2012). Recently, Brewer et al. (2014) surveyed over 300 professional African American women and found that attitudes toward research participation were generally favorable, yet many women (over 60%) had never participated in research, and nearly half (46%) reported not being invited to participate. Importantly, 24% of African American women in this study agreed with the statement: “participation in research is risky.” The present paper reports the findings of a message-framing manipulation embedded within the study reported by Brewer and colleagues.

The effect of persuasive messaging on African American women’s intention to participate in health-related research has not been examined, yet a rich body of literature in health communication suggests that the way in research participation is framed (gain vs. loss) may affect decisions regarding participation. Gain- and loss-framed messages emphasize, respectively, either the benefits of performing the behavior or the negative consequences (losses) of not performing the behavior; meta-analyses have summarized the literature addressing message framing effects on attitudes and intentions (Gallagher & Updegraff, 2012), preventive health behaviors (O’Keefe & Jensen, 2007) and detection health behaviors (O’Keefe & Jensen, 2008, 2009). The differential impact of gain- and loss-framed messages are based in prospect theory, which holds that presenting potential losses is more motivating when individuals consider performing a behavior that is risky (uncertain outcome) whereas focusing on potential gains is more motivating for behaviors not believed to be risky (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). Furthermore, research has identified moderators of message-framing effects, including perceived risk (Rothman & Salovey, 1997), self-efficacy (van ‘t Riet, Ruiter, Werrij, & De Vries, 2008, 2010; Werrij, Ruiter, van ‘t Riet, & De Vries, 2010), and other dispositional factors recently reviewed by Covey (2014).

This study expands on these findings to assess the impact of a gain- vs. loss-framed message on intention to participate in health-related research among African American women and additionally, to evaluate whether message framing effects are moderated by perceived risk or self-efficacy in the behavioral context of research participation.

Methods

Study Design and Population

An overview of the methods for this cross-sectional study, including a description of the study population, is included in Brewer et al. (2014). Briefly, the study was conducted in conjunction with the 38th National Assembly of The Links, Incorporated, in June 2012. The Links, Incorporated is an African American service organization with a membership of over 12,000 professional women of color. The organization’s focus on health initiatives and interest in partnering with health agencies fostered mutual interest in understanding the attitudes and experiences of Link members with regard to participation in health-related research.

Procedures

Over 2,000 study packets were distributed along with the meeting registration materials to Assembly attendees. Study packets contained an introductory letter describing the research, an oral consent script, and a survey booklet with instructions for returning completed surveys to study staff located in a booth in the exhibition hall. The introductory letter stated that the research project was designed to learn about African American women’s thoughts and opinions about health research, contained the logos of the partnering organizations (Mayo Clinic and The Links, Incorporated), and contained the signatures of investigators representing both organizations. Study packets containing gain- or loss-framed messages within the survey were distributed in random order to attendees. All study materials and procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Upon return of a completed survey, women were given a thank-you gift and offered the opportunity to register onsite for ResearchMatch (RM) using a laptop computer located in the booth. RM is a disease-neutral web-based recruitment registry designed to match volunteers with researchers (Harris et al., 2012). Custom-designed RM portals were created for Link members wishing to register after completing the survey. Women were directed by study staff to the portal that corresponded to the message frame they received in their survey booklet (gain or loss) to enable group-based tallies at the conclusion of the study. Members with limited time at the Assembly who indicated interest in registering later were given a card containing the web address and QR code to the RM portal (gain or loss) that matched the survey version they returned. The web portals remained open for one month following the Assembly to capture offsite registrations. A multimedia health education video featuring members of The Links, Incorporated and other African American women discussing their experiences as research participants played on a continuous loop near the survey drop-off location. The video, entitled: “You Can Make a Difference,” raised awareness of the importance of research participation by minorities and women and provided a larger context for our study.

Message Development

An introductory passage on the first page of the survey booklet provided the context for the message framing manipulation. The passage contained information adapted from Project I.M.P.A.C.T. (Increased Minority Participation and Awareness of Clinical Trials) (National Medical Association, 2008). Passages either emphasized the benefits to the African American community of participating in health-related research or the losses associated with not participating. The passages were pilot-tested among 18 Links members at a community health event. Women receiving the loss-framed passage (n=9) rated the message as more negative (“focused heavily on the risks of not participating in health-related research”) as compared to women receiving the gain-framed passage (n=9), who rated the message as more positive (“focused heavily on the benefits of participating in health-related research”), although the difference did not reach traditional levels of statistical significance (p=0.46). Overall, ratings (from “not at all” to “extremely”) did not significantly differ between the gain- and loss-framed messages on the following characteristics: informative, confusing, interesting, believable, understandable, relevant to me, and convincing (all p>0.22). Relative to the gain-framed message, the loss-framed message was rated as marginally more memorable (p=0.054). Finally, messages were evaluated for their ability to elicit positive or negative emotional reactions and their overall persuasiveness. Gain- and loss-framed messages did not differ on their ability to elicit the following feelings: empowered, anxious, reassured, informed, fearful, proud, angry, or vulnerable (all p>0.28), however those who received the loss-framed message reported slightly higher ratings for feeling “valued” than those who received the gain-framed message (p=0.47). Lastly, the messages did not appear to differ in general persuasiveness, with 6/9 receiving the loss-framed message (vs. 5/9 receiving the gain-framed message) reporting that reading the message made them more likely to participate in research in the future (p=0.63). Importantly, neither message resulted in any women indicating that she would be “less likely to participate in research in the future” as a result of exposure to the message content. The final versions of the introductory passages containing the framing manipulation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Gain and Loss Framed Messages

| Gain Framed | Loss Framed |

|---|---|

| According to the National Medical Association, health research is an important part of preventing disease as well as finding cures for disease. In fact, many of the treatments that save lives today are based on yesterday’s research studies. Today, federal laws are in place to protect African American research participants from exploitation and abuse in health-related research. If you agree to participate in research when offered the opportunity you will help contribute valuable knowledge regarding how new medicines or treatments work for African-Americans and the benefits of research will reach the African- American community more quickly. Presently, African Americans, particularly African American women, are underrepresented in the study of many conditions that affect them, especially heart disease and breast cancer. By participating in health-related research, you have the opportunity to help determine what is best for African American women’s health and wellness now and for future generations. When you accept an invitation to participate in health-related research, you receive the possible benefit of helping researchers find answers and best medicines for you, your children, and grandchildren. Thus, your decision to participate may not only benefit you, but others as well. When you participate in research studies, you have the power to make a difference in medicine and the future health of African American women! |

According to the National Medical Association, health research is an important part of preventing disease as well as finding cures for disease. In fact, many of the treatments that save lives today are based on yesterday’s research studies. In the past, federal laws did not exist to protect research participants, and African Americans were exploited and abused in some health-related research. If you decline to participate in research when offered the opportunity, you will not help contribute valuable knowledge regarding how new medicines or treatments work for African- Americans and the benefits of research will reach the African-American community more slowly. Presently, African Americans, particularly African American women, are underrepresented in the study of many conditions that affect them, especially heart disease and breast cancer. By not participating in health-related research, you lose the opportunity to help determine what is best for African-American women’s health and wellness now and for future generations. When you decline an invitation to participate in health- related research, you deny yourself the possible benefit of helping researchers find answers and best medicines for you, your children, and grandchildren. Thus, your decision not to participate may not only be a loss to you, but others as well. When you don’t participate in research studies, you forfeit the power to make a difference in medicine and the future of African American women! |

The survey included socio-demographic questions such as age, education, marital status, number of children, employment and insurance status, prior participation in health-related research (yes or no), and years of Links membership. Self-efficacy, or an individual’s perceived ability to perform a behavior (Bandura, 1986) was assessed by the item “I feel I have __over participating in a health-related research study,” using a 7-point Likert scale with the anchors “complete control” (1) and “no control” (7). Scores were dichotomized for analysis into low (raw scores 4–7) or high self-efficacy (1–3). The item “Participation in research is risky” was measured using a 5-point “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5) Likert scale. Perceived risk score were dichotomized for analysis as low (1–3) or high (4–5). The primary outcome variable, intention to participate in a health-related research study, was measured on a 7-point “definitely no” (1) to “definitely yes” (7) rating scale. ResearchMatch registration provided a secondary outcome of interest and served as a strong behavioral proxy for research participation, as women who registered were essentially declaring their willingness to be contacted by investigators and screened as a potential study participant. For this outcome variable, group-based tallies were provided by RM after the portals “closed.” Specifically, we were provided the frequency (number) of women who accessed the website and the frequency (number) of women who completed registration for each message frame (group). These data are reported descriptively. Group-based tallies upheld the rules regarding access to names in RM however they would not enable us to conduct individual-level analyses. Thus, to enable analyses that linked the RM registration outcome to individual survey data, we used our own direct observation of onsite registration. Specifically, when participants returned their survey, study staff collected it by hand, looked at whether they received the gain- or loss-framed message in their survey, and documented RM registration in a “Research Use Only” box on the inside cover of the survey by checking one of three boxes designated “R”, “DR” or “NI” for registered (onsite), did not register onsite (but a portal information card was given) or not interested in registering (did not register onsite and declined a portal information card), respectively.

Statistical Methods

Participant characteristics were compared between gain- versus loss-framed messages using t-tests or chi-square tests, as appropriate. Mean intention to participate was examined by message frame (gain vs. loss), self-efficacy (high vs. low) and perceived risk of research participation (high vs. low) using linear regression with robust standard errors; similar overall comparisons were made for RM registration using logistic regression. The effect of message framing on intention to participate in health-related research was evaluated using linear regression with robust standard errors. The effect of message framing on RM registration was evaluated using logistic regression models. Regression models were developed for intention and RM registration by applying the following a priori strategy: 1) to assess the independent effect of message frame (gain vs. loss) ; 2) to assess the effect of message frame adjusting for self-efficacy; 3) to assess the effect of message frame interacting with self-efficacy (self-efficacy as an effect modifier); 4) to assess the effect of message frame adjusting for perceived risk; and 5) to assess perceived risk as an effect modifier of message frame (evaluate the perceived risk × message frame interaction). All analyses were repeated while adjusting for prior research participation and having children (variables on which the message groups differed), and having seen the “You Can Make a Difference” video prior to completing the survey. Descriptive data are presented as means (M) ± standard deviation (SD), frequencies (n), and percentages (%). Analyses were conducted using STATA (version 11.2, College Station, TX); a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

A total of 391 women returned completed surveys. Ten surveys were returned by women who indicated that they participated in the pilot-testing of the message framing manipulation; these were excluded from further analysis, leaving a final sample size of 381 participants - 187 in the gain-framed message group and 194 in the loss-framed message group. Based upon the work of van ’t Riet and colleagues (2008, 2010) and Werrij et al. (2011), we anticipated an effect size of 1 as a reasonable difference. With 175 women in each of the two study groups, we would have had 99% power to detect such an effect size. The precise sample size in this study was determined by the number of participants; with 381 participants, this study had just over 99% power.

Participant Characteristics

Overall, a majority of participants were married, educated, and employed full-time (Table 2). A higher proportion of participants in the loss-framed group as compared to the gain-framed group reported prior participation in health-related research (50.5% vs. 31.5%, p<0.001; Table 2). In addition, a higher proportion of participants in the gain-framed group as compared to the loss-framed group reported having 1 or more children (85.0 vs. 75.8%, p=0.02). On average, intention to participate in research was 4.90 ±1.66, with 57% of women reporting an intention score greater than 4 on the 7-point scale, with higher scores reflecting “definitely yes.” Self-efficacy regarding research participation was also favorable (M=2.1 ± 1.5, with women generally indicating high perceived control over their ability to participate in research. Approximately 25% of women expressed agreement that participation in research is risky (Brewer et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Selected Participant Characteristics by Message Frame (N=381)

| Characteristic | Gain Frame n=187 n (%) |

Loss Frame n=194 n (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | 0.72 | ||

| Not Married | 68 (36.4) | 74 (38.1) | |

| Ever Married | 119 (63.6) | 120 (61.9) | |

| Educational Attainment | 0.93 | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree or Below | 35 (18.7) | 37 (19.1) | |

| Graduate or Professional Degree | 152 (81.2) | 157 (80.9) | |

| Number of Children | 0.02 | ||

| 0 | 28 (15.0) | 47 (24.2) | |

| 1 or More | 159 (85.0) | 147 (75.8) | |

| Health Insurance Status | 0.09 | ||

| Yes | 185 (98.4) | 185 (100.0) | |

| No | 3 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Employment Status | 0.69 | ||

| Full Time | 109 (58.3) | 117 (60.3) | |

| Part Time or Other | 78 (41.7) | 77 (39.7) | |

| Household Income | 0.56 | ||

| < $99,999 | 61 (33.5) | 63 (34.4) | |

| $100,000 or greater | 121 (66.4) | 120 (65.5) | |

| Viewed Research Participation Video prior to completing survey |

0.56 | ||

| Yes | 31 (16.6) | 28 (14.4) | |

| No | 156 (83.4) | 166 (85.6) | |

| Prior Knowledge of ResearchMatch | 0.32 | ||

| Yes | 10 (5.4) | 6 (3.2) | |

| No | 176 (94.6) | 182 (96.8) | |

| Prior Research Participation | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 59 (31.6) | 98 (50.5) | |

| No | 128 (68.5) | 96 (49.5) | |

| Years in Links Mean (SD) | 14.3 (10.5) | 14.5 (10.1) | 0.87 |

| Age, in years Mean (SD) | 57.9 (10.6) | 58.0 (9.2) | 0.92 |

Intention to Participate in Research

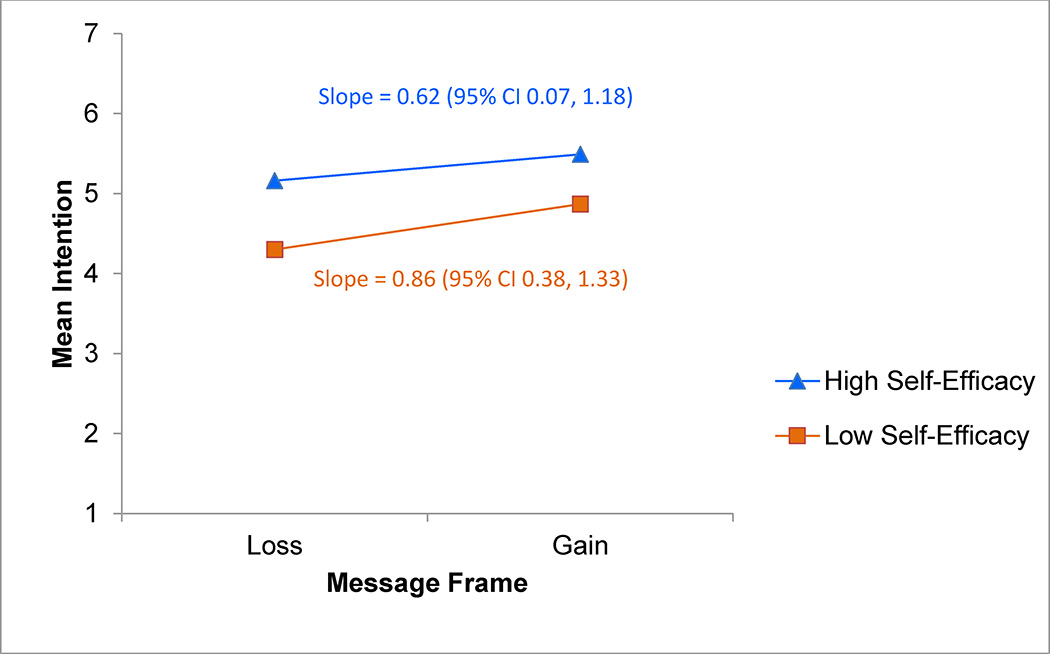

Intention scores did not differ by message frame; Mgain = 4.88 ±1.70 vs. Mloss = 4.93 ±1.62 (p=0.80; Table 3, Model 1). After adjusting for self-efficacy, intention remained unassociated with message frame (p=0.81; Table 3, Model 2). Irrespective of message frame, high self-efficacy was associated with a greater intention to participate in research (over 1 point higher on the 7-point scale, p<0.001; Table 3, Model 2). A statistically significant message frame × self-efficacy interaction (p=0.006; Table 3, Model 3) indicated that the favorable effect of high self-efficacy on intention to participate was somewhat less for women receiving the gain-framed message than for women receiving the loss-framed message (see Figure 1). In a similar set of analyses, we examined the association between message framing and perceived riskiness of research participation (Table 3, Models 4 and 5). High perceived risk (vs. low) was associated with lower intention to participate in research after adjusting for message frame (p=0.007).

Table 3.

Linear Regression Analysis of Intention to Participate in Research

| Coefficienta | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Message Frame (Gain) | −0.04 | −0.39, 0.30 | 0.80 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Message Frame (Gain) | −0.04 | −0.37, 0.29 | 0.81 |

| Self-efficacy | 1.11 | 0.68, 1.54 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 (Message Frame, Self-efficacy) | |||

| Gain-frame × Self-efficacy | −0.23 | −0.40, -0.07 | 0.006 |

| Model 4 | |||

| Message Frame (Gain) | −0.08 | −0.42, 0.26 | 0.65 |

| Perceived Risk | −0.60 | −1.03, -0.16 | 0.007 |

| Model 5 (Message Frame, Perceived Risk) | |||

| Gain-frame × Perceived risk | 0.12 | −0.76, 1.00 | 0.79 |

Coefficients reflect the unstandardized scale of intention to participate in research, a 7-point “definitely no” (1) to “definitely yes” (7) rating scale.

Figure 1.

Mean Intention to Participate in Research by Message Frame and Self-Efficacy

ResearchMatch Registration

Group-level tallies provided by RM one month after data collection at The Links’ Assembly revealed that a total of 177 women accessed RM through one of the custom Links portals: 93 through the portal for recipients of the gain-framed message and 84 through the portal for recipients of the loss-framed message. Of the 177 women who accessed RM, 81 (46%) women actually completed registration: registration rates by group were 38/93 (41%) for those who entered RM through the portal associated with the gain-framed message and 43/84 (51%) for those who entered RM through the portal associated with the loss-framed message (Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.66, p=0.18). By direct observation, 82 women entered RM using one of the on-site computers set up for this purpose (coded “R” by study staff): 42/187 (22%) receiving the gain-framed message and 40/194 (21%) receiving the loss-framed message (OR = 1.11, p=0.66).

The results of the logistic regression models do not support an effect of message framing on RM registration (Table 4, Models 1, 2, and 4). However, self-efficacy was associated with RM registration; specifically, high self-efficacy (vs. low) was associated with a 2.62 higher odds of RM registration when adjusted for message frame (p=0.008; Table 4, Model 2). The interaction of self-efficacy and message framing was not significant. Perceived riskiness of research participation was unassociated with RM registration in any of the models (Table 4, Models 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Registration for ResearchMatch Registration

| Odds Ratio |

95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Message Frame (Gain) | 1.12 | 0.68, 1.82 | 0.66 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Message Frame (Gain) | 1.10 | 0.67, 1.80 | 0.71 |

| Self-efficacy | 2.62 | 1.29, 5.33 | 0.008 |

| Model 3 (Message Frame, Self-efficacy) | |||

| Gain-frame × Self-efficacy | 1.03 | 0.82, 1.30 | 0.80 |

| Model 4 | |||

| Message Frame (Gain) | 1.09 | 0.67, 1.79 | 0.72 |

| Perceived Risk | 0.61 | 0.32, 1.14 | 0.12 |

| Model 5 (Message Frame, Perceived Risk) | |||

| Gain-frame × Perceived Risk | 0.82 | 0.23, 2.92 | 0.75 |

Similar results were obtained throughout when the models were adjusted for prior research participation, having children, and seeing the “You Can Make a Difference” video (data not shown).

Discussion

This study contributes to a growing body of evidence that professional African American women hold favorable attitudes and positive intentions regarding participation in health-related research (Brewer et al., 2014; Powell-Young & Spruill, 2013). Furthermore, this study revealed high self-efficacy regarding research participation among a majority of The Links, Incorporated respondents, and as expected, positive associations between self-efficacy, intention, and registration behavior. When considered within the context of well-established theoretical frameworks surrounding voluntary health-related behaviors (e.g., social cognitive theory, theory of planned behavior), these findings suggest that efforts directed toward highlighting opportunities to engage in research may be more advantageous than efforts directed toward influencing personal attitudes about research participation, but further work is needed. Given the general conditions of favorable attitudes, high self-efficacy, and positive intentions regarding future research participation, our data also suggest receptivity to communications that invite participation. Our study design included careful development of persuasive messages regarding research participation and examination of message framing effects in targeted communications to African American women.

Overall, presenting a gain- vs. loss-framed message to African American women did not result in more favorable outcomes with regard to registration for RM, thus our data do not support message framing effects in this context. Similarly, we did not find support for the underlying tenets of prospect theory with regard to risk perception (uncertainty), as in this investigation, the negative association between perceived risk and intention to participate in research did not differ by message frame. The failure to find an advantage of a loss-framed message when outcomes are uncertain in the context of research participation was also reported by Evangeli, Kafaar, Kagee, Swartz, and Bullemar-Day (2013) in the context of willingness to participate in a hypothetical HIV vaccine trial. As suggested by Evangeli et al. (2013), we directly assessed perceptions of risk and self-efficacy regarding research participation in our study, and obtained findings consistent with the work of van ’t Riet et al. (2008, 2010); women with high self-efficacy to participate in research reported greater intentions toward participating when receiving a loss-framed message as compared to a gain-framed message. The robustness of this finding - in the context of accounting for other factors such as prior experience as a research participant and having viewed a video presentation about the importance of research participation - warrants further investigation.

Our efforts to reach a unique, and potentially influential group of African American women through The Links, Incorporated demonstrated promise; however, they also showed that challenges remain. For instance, while the majority of women indicated a willingness to participate in research, fewer than one in four actually registered for RM when given the opportunity to do so after completing the survey. This finding may reflect deeper issues related to perceived imbalance of power, trust, and lack of understanding of the research process (Corbie-Smith et al., 2002; Corbie-Smith, Thomas, Williams, & Moody-Ayers, 1999; George, Duran, & Norris, 2014; Lang et al., 2013), variations in the intention-behavior relationship (Ajzen, 2011; Sheeran, 2002), or simply the reality of competing demands during the Assembly, particularly given the time and multiple information fields involved in completing RM registration.

When given the opportunity to do so as part of this investigation, 82 African American women registered with RM and became part of a national pool of potential study volunteers. This outcome of our work is not insignificant, particularly at a time when greater emphasis is placed on identifying and enrolling women and minorities in a variety of study types, including clinical trials and genetic studies. Leveraging increasing positive regard for medical research among professional African American women will require researchers to engage in enhanced dialogue and continued trust building, particularly among religious institutions and other community-based organizations, (Minkler, 2004; Taylor, 2009).

The strengths of this investigation include its strong theoretical foundation, its actual contribution to research volunteerism through RM, and the use of a collaborative community-engaged approach. The study was adequately powered and the framed messages were adapted from project I.M.P.A.C.T. and pilot-tested to ensure their believability, trustworthiness, and relevance. These must be weighed against the limitations, which include lack of tight experimental control in the research setting; this resulted in an inability to calculate a “true” response rate. Further, the collection of data at a single, large, national event for the target population excluded The Links, Incorporated members who did not attend this particular meeting and placed our research in a setting somewhat limited by space and competing priorities. It is possible that having only a few laptops available for on-site RM registration and long queues discouraged registration in RM, however the RM sites were kept open for one month following the study to minimize the impact of this limitation. Moreover, we report both “group-based” registration after one month following the study (provided by RM for the gain and loss portals) and individual registration as directly observed on-site. We conservatively presumed “no registration” for women who were not directly observed registering on-site, which may have biased our results. Members of The Links, Incorporated are a select group of professional African American women recognized for their service and leadership in their communities. While it would be unreasonable to assume that our findings among this group of women are generalizable or representative of all African American women, The Links, Incorporated represent a population of minority women previously not regarded by the research community. Furthermore, our experience with The Links, Incorporated illustrates the promise of establishing relationships with other organized minority women’s organizations to better understand and promote research participation. Strengths and weaknesses noted, our study makes theoretical and practical contributions to the field of health communication and informs future strategies to meaningfully and effectively include women and minorities in health-related research.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Mayo Clinic Office of Health Disparities Research (OHDR). OHDR had no involvement in the analysis or interpretation of the data or the decision to submit this article for publication. Drs. Balls-Berry and Enders are supported, in part, by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Special thanks to Michael (Woon Tzu) Lin (Mayo Clinic) and to Drs. Paul Harris and Laurie Lebo (Vanderbilt University) for creating the RM portals for this study.

Footnotes

The authors do not have any relevant disclosures to report related to this research.

Contributor Information

Joyce E. Balls-Berry, Mayo Clinic.

Sharonne Hayes, Mayo Clinic.

Monica Parker, The Links, Incorporated, Emory University School of Medicine.

Michele Halyard, The Links, Incorporated, Mayo Clinic.

Felicity Enders, Mayo Clinic.

Monica Albertie, Mayo Clinic.

Vivian Pinn, The Links, Incorporated.

Carmen Radecki Breitkopf, Mayo Clinic.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health. 2011;26(9):1113–1127. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Branson RD, Davis K, Jr, Butler KL. African Americans' participation in clinical research: Importance, barriers, and solutions. American Journal of Surgery. 2007;193(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer LC, Hayes SN, Parker MW, Balls-Berry JE, Halyard MY, Pinn VW, Radecki Breitkopf C. African American women's perceptions and attitudes regarding participation in medical research: The Mayo Clinic/The Links, Incorporated partnership. Journal of Women's Health. 2014;23(8):681–687. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St. George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(21):2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(9):537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey J. The role of dispositional factors in moderating message framing effects. [Review] Health Psychology. 2014;33(1):52–65. doi: 10.1037/a0029305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangeli M, Kafaar Z, Kagee A, Swartz L, Bullemor-Day P. Does message framing predict willingness to participate in a hypothetical HIV vaccine trial: An application of Prospect Theory. AIDS care. 2013;25(7):910–914. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.748163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;43(1):101–116. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(2):e16–e31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Scott KW, Lebo L, Hassan N, Lightner C, Pulley J. ResearchMatch: A national registry to recruit volunteers for clinical research. Academic Medicine. 2012;87(1):66–73. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823ab7d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller C, Balls-Berry JE, Nery JD, Erwin PJ, Littleton D, Kim M, Kuo WP. Strategies addressing barriers to clinical trial enrollment of underrepresented populations: A systematic review. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2014;39(2):169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.08.004. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kanarek NF, Kanarek MS, Olatoye D, Carducci MA. Removing barriers to participation in clinical trials, a conceptual framework and retrospective chart review study. Trials. 2012;13:237. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, Kelkar VA, Byrd JR, Edwards CL, Pericak-Vance M, Byrd GS. African American participation in health-related research studies: Indicators for effective recruitment. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2013;19(2):110–118. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31825717ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the "outside" researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(6):684–697. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Medical Association. You've got the power. What you should know about clinical trials. National Medical Association-Project IMPACT. 2008 Retrieved from http://impact.nmanet.org/downloads/power_booklet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe DJ, Jensen JD. The relative persuasiveness of gain-framed and loss-framed messages for encouraging disease prevention behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Health Communication. 2007;12(7):623–644. doi: 10.1080/10810730701615198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe DJ, Jensen JD. Do loss-framed persuasive messages engender greater message processing than do gain-framed messages? A meta-analytic review. Communication Studies. 2008;59(1):51–67. [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe DJ, Jensen JD. The relative persuasiveness of gain-framed and loss-framed messages for encouraging disease detection behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Communication. 2009;59:296–316. doi: 10.1080/10810730701615198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Young YM, Spruill IJ. Views of Black nurses toward genetic research and testing. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2013;45(2):151–159. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(1):3–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P. Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M, editors. European Review of Social Psychology. Vol. 12. Chichester, NY: Wiley; 2002. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JY. Recruitment of three generations of African American women into genetics research. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2009;20(2):219–226. doi: 10.1177/1043659608330352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van 't Riet J, Ruiter RAC, Werrij MQ, De Vries H. The influence of self-efficacy on the effects of framed health messages. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38(5):800–809. [Google Scholar]

- van 't Riet J, Ruiter RA, Werrij MQ, De Vries H. Self-efficacy moderates message-framing effects: The case of skin-cancer detection. Psychology & Health. 2010;25(3):339–349. doi: 10.1080/08870440802530798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werrij MQ, Ruiter RA, van 't Riet J, De Vries H. Self-efficacy as a potential moderator of the effects of framed health messages. Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(2):199–207. doi: 10.1177/1359105310374779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]