Abstract

Background

Chinese medicines have been used for chronic heart failure (CHF) for thousands of years; however, the status of traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) used for CHF has not been reported. This review was carried out in the framework of a joint Sino-Italian Laboratory.

Objective

To investigate the baseline of clinical practice of TCMs for CHF, and to provide valuable information for research and clinical practice.

Methods

The authors included articles about the use of TCMs for the treatment of CHF by searching the Chinese Journal Full-text Database (1994 to November 2007).

Results

In all, 1029 papers were included, with 239 herbs retrieved from these. The most commonly used herbs included Huangqi (Radix Astragali), Fuling (Poria), Danshen (Radix Salviae Miltiorrhiae), Fuzi (Radix Aconiti Lateralis Preparata) and Tinglizi (Semen Lepidii). Modern Chinese patent medicines (produced by pharmaceutical companies) and traditional prescriptions (comprising several herbs) are the application forms of these drugs. Shenmai, Shengmai and Astragalus injections were the most commonly used Chinese patent medicines. Some classic prescriptions (including Zhenwu decoction, Shengmai powder and Lingguizhugan decoction) were also frequently used. The effectiveness and safety of the TCMs were both satisfactory, and the traditional Chinese medicine and western medicine therapy could significantly improve the clinical effectiveness and reduce some of the adverse reactions from western medicines used alone.

Conclusion

The authors have acquired overall information about the clinical application of TCMs for CHF. Modern pharmacology has provided limited evidence for the rationality of this clinical use. Further research is needed to provide more evidence.

Keywords: Chronic heart failure, traditional Chinese medicine, clinical practice

Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a complex clinical syndrome that can result from any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood.1 Heart failure (HF) is the end stage of cardiac disease. The American Heart Association (AHA) Statistics Committee indicates: heart failure incidence approaches 10 per 1000 population after 65 years of age. The estimated direct and indirect cost of HF in the USA for 2008 is $34.8 billion.2

Over the past several decades, various types of drugs have been applied to treat CHF. Several have been proven effective to improve the syndromes of CHF, but usually patients show poor compliance because of adverse effects and especially for long-term use. In contrast, traditional Chinese medicines have certain advantages for the treatment of CHF, as they are multilevels multitargeted, and they have few side effects.3 However, the clinical application for CHF has not been systematically analysed. To investigate their clinical use and to gain valuable information for research and clinical practice, we carried out a comprehensive review.

Materials and methods

Literature search

We searched the Chinese Journal Full-text Database (1994 to November 2007), which is the largest Chinese literature database. The main key words were ‘traditional Chinese medicine,’ ‘Chinese herbs,’ ‘Chinese patent medicine’ and ‘chronic heart failure.’

To determine which studies should be assessed further, each of the records retrieved was independently scanned for title, abstract and key words by two reviewers. If the information referred to Chinese medicines for the treatment of CHF, the full text was obtained for further assessment. Papers were excluded when problems occurred with duplicate publication, reviews, aetiology or diagnostics research, animal experiment and research on acupuncture, qigong, massage or other treatments.

Data extraction and analysis

We established a database (using Microsoft Access 2003; Microsoft, Seattle, Washington) to extract the data. Information on publication, type of study, participants, medication, prescription, herb names and adverse side effects of drugs was imported into the database for analysis. Six researchers were trained to extract the data from each paper included according to unified specifications. All inconsistencies were revised after the database was checked by two reviewers.

Frequencies of single herb, Chinese patent medicines and compound prescriptions of TCMs were calculated. Each category was reported according to the frequencies of use. We also analysed the efficacy and safety of TCMs based on the results of clinical trials.

Results

Outcomes of selection of the literature

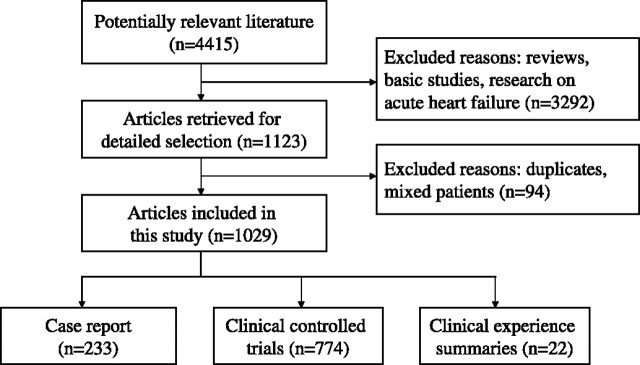

According to the search strategy, we obtained 4415 potentially relevant papers (see Figure 1). After selection according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1029 papers were identified as directly relevant. Of these, 774 were controlled clinical trials (CCTs), 233 were case reports, and 22 were clinical experience summaries. The total number of participants included in the 1029 studies was 77 691.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the articles selection for this study.

Clinical application of single Chinese herb

In all, 239 Chinese herbs were used in the 1029 papers. The drugs that had a frequency higher than 300 were Huangqi (Radix Astragali), Fuling (Poria), Danshen (Radix Salviae Miltiorrhiae), Fuzi (Radix Aconiti Lateralis Preparata) and Tinglizi (Semen Lepidii).

Thirty herbs with a frequency of more than 50 in which six herbs were documented as benefiting vital energy (Yiqi) and improving heart function, including Baizhu (Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae), Gancao (Radix Glycytthizae) and Renshen (Radix Ginseng), eight herbs were specifically related to the promotion of blood flow (Huoxue) such as Danshen (Radix Salviae Miltiorrhiae), Chuanxiong (Rhizoma Chuanxiong) and Honghua (Flos Carthami). Seven herbs reduced water retention (Lishui), including Fuling (Poria), Guizhi (Ramulus Cinnamomi) and Zexie (Rhizoma Alismatis). Huangqi (Radix Astragali) had effects that not only benefited vital energy but also reduced water retention. Similarly, Yimucao (Herba Leonuri) could both promote blood flow and reduce water retention.

Clinical application of Chinese patent medicines

The Chinese patent medicines refer to some kinds of dosage form, based on the theory of TCM, and incorporating Chinese herbal medicine as raw material. They are produced under the guidance of the formula principle and the science technology. The commonly used formulations include pills, tablets, injections and capsules. Chinese patent medicines are characterised by their ease of administration and storage, and by their rapid onset of action and quality control.

Among the Chinese patent medicines for CHF, injections with Shenmai, Shengmai, Astragalus and Shenfu were used frequently (table 1).

Table 1.

Chinese patent medicines for chronic heart failure and their main components

| Name | Components (Latin name) |

|---|---|

| Shenmai injection | Radix Ginseng Rubra, Raidix Ophiopogonis |

| Shengmai injection | Radix Ginseng Rubra, Raidix Ophiopogonis, Fructus Schisandrae |

| Astragalus injection | Radix Astragali |

| Shenfu injection | Radix Ginseng Rubra, Radix Aconiti Lateralis Preparata |

| Compound salvia injection | Radix Salviae Miltiorrhiae, Lignum Dalbergiae Odoriferae |

| Puerarin injection | Radix Puerariae |

| Salvia injection | Radix Salviae Miltiorrhiae |

| Wenxin particles | Radix Codonopsis, Rhizoma Polygonati, Radix Seu Rhizoma Nardostachyos, Radix Notoginseng |

| Shenqifuzheng injection | Radix Codonopsis, Radix Astragali |

| Tongxinluo capsule | Radix Ginseng, Hirudo, Scorpio, Lignum Santali Albi, Eupolyphaga Seu Steleophaga, Scolopendra, Olibanum, Periostracum Cicadae, Lignum Dalbergiae Odoriferae, Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Semen Ziziphi Spinosae, Broneolum Syntheticum |

Clinical application of traditional prescriptions of Chinese herbs

Traditional prescriptions of Chinese herbs can include a single Chinese herb or a number of herbs, depending on the premise of syndrome differentiation, according to the principle of the compatibility for the prescription. These prescriptions are characterised by the individualised treatments.

Zhenwu decoction, Shengmai preparations and Lingguizhugan decoction were used frequently as the classic prescriptions for CHF (table 2).

Table 2.

Classic prescriptions for chronic heart failure and their main components

| Name | Components (Latin name) |

|---|---|

| Zhenwu decoction | Poria, Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae, Raidix Paeoniae Alba, Radix Aconiti Lateralis Preparata, Rhizoma Zingiberis Recens |

| Shengmai powder/yin | Radix Ginseng, Raidix Ophiopogonis, Fructus Schisandrae |

| Linguizhugan decoction | Poria, Ramulus Cinnamomi, Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae, Radix Glycytthizae |

| Buyanghuanwu decoction | Radix Astragali, Radix Angelicae Sinensis, Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Pheretima, Rhizoma Chuanxiong, Semen Persicae, Flos Carthami |

| Shenfu decoction | Radix Ginseng, Radix Aconiti Lateralis Preparata |

| Wuling powder | Poria, Polyporus, Rhizoma Alismatis, Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae, Ramulus Cinnamomi |

| Fumai decoction | Radix Glycyrrhizae preparata, Radix Ginseng, Rhizoma Zingiberis Recens, Ramulus Cinnamomi, Raidix Ophiopogonis, Radix Rehmanniae, Semen Cannabis, Fructrs Jujubae, Colla Corii Asini |

| Xuefuzhuyu decoction | Radix Angelicae Sinensis, Radix Rehmanniae, Semen Persicae, Flos Carthami, Fructus Aurantii, Radix Paeoniae Rubra, Radix Bupleuri, Rhizoma Chuanxiong, Radix Platycodi, Radix Acanthopanacis Bidentatae, Radix Glycytthizae |

| Mufangji decoction | Cocculus Trilobus DC, Gypsum Fibrosum, Ramulus Cinnamomi, Radix Ginseng |

| Shenfulongmu decoction | Radix Ginseng, Radix Aconiti Lateralis Preparata, Os Draconis Rhizoma Zingiberis Recens, Ziziphus jujuba Mill, Concha Ostreae |

| Baoyuan decoction | Radix Ginseng, Radix Astragali, Cortex Cinnamomi, Radix Glycytthizae |

Clinical application of TCMs combined with western medicines

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were recognised as the more valuable research design to access the efficacy and safety. Therefore, we further analysed 684 RCTs included in our study. Among these RCTs, 626 studies took effective rate as an evaluation index. Four hundred and forty-two RCTs with 39 081 participants (21 034 patients in treatment group) of the 626 RCTs used the conventional treatment based on the ACC/AHA 2005 guideline in control group. The conventional treatment mainly included the combined application of drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), β-blockers, kinds of diuretics and digitalis. The interventions of the treatment group of the 442 studies were these conventional treatments plus TCMs. (The most commonly used TCMs are listed in tables 1, 2.)

We changed the three grades of ranked data into two grades (effective and invalid). The effective rate of treatment group was 91.08% (19 158 of 21 034) compared with 73.97% (13 349 of 18 047) in the control group. In addition, 28 trials with 2558 participants (1366 in treatment group) of the 442 RCTs reported the data on mortality. There were statistically significant differences in mortality between the treatment (59/1366) and control (143/1192) groups. These results were similar to those in the systematic reviews reported by Chen4 and Wu.5

Our study indicated that the combination of TCMs and western medicines could reduce mortality and improve the effective rate compared with western medicines used alone.

Analysis of potential adverse effects of the drugs based on the clinical trials

Adverse effects of the drugs based on the clinical trials were also analysed in our study. One hundred and eighty-six studies (18.08%) reported that no side effects occurred at the end of their treatment, and 706 studies (68.61%) did not mention any information on side effects. Another 137 studies with the patients of 12 063 reported the adverse reactions after the treatment. No treatment-related deaths were reported.

Fourteen of the 137 studies including 714 patients with the intervention of Chinese medicines used alone reported the adverse reactions. Two of the 14 studies did not provide the specific number of patients with side effects. The main clinical manifestations of the 45 patients who suffered adverse reactions in the other 12 studies are listed in table 3.

Table 3.

Adverse reactions of patients using Chinese medicines alone

| Adverse reaction | No | Treatment and outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea, vomiting/abdominal distension, diarrhoea | 27 | Short-term withdrawal that is better/improved with symptomatic treatment/improved with no special treatment |

| Arrhythmia | 8 | Short-term withdrawal that is better |

| Dry mouth/feverish dysphoria | 10 | Improved with no special treatment |

One hundred and six RCTs were included in the 137 studies which reported the side effects. In these RCTs, there were 63 studies with similar conventional treatments in the control group which combined the cardiotonic, diuretics and vasodilator together based on the ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines. Conventional treatments of control group added TCMs were the interventions of the treatment group. The total number of the patients in the 63 RCTs was 5907. The rate of side effects was 4.08% (130/3186) in the treatment group compared with 9.81% (267/2721) in the control group. After symptomatic treatment or decreasing the intravenous injection speed the adverse reactions reduced or disappeared. The number of patients with more than 10 side effects is listed in table 4 for comparison in both treatment and control group.

Table 4.

Adverse reactions in randomised controlled trials

| Treatment group (no) | Control group (no) | |

|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte imbalance | 14 | 85 |

| Digitalis poisoning | 13 | 65 |

| Arrhythmia | 9 | 40 |

| Dry cough | 6 | 20 |

| Nausea/diarrhoea | 14 | 20 |

| Hypotension | 1 | 11 |

| Dizziness/headache | 15 | 10 |

| Dry mouth/feverish dysphoria | 37 | 1 |

| Drowsiness | 17 | 0 |

Discussion

With the ageing global population, the incidence of CHF continues to increase year by year.6 Thus, finding a pharmacotherapy or non-drug therapy with good efficacy and safety for CHF has become a hot issue, receiving considerable attention by medical fields worldwide.

This descriptive study, according to information provided by 1029 studies, has reviewed the current situation of the clinical application of TCMs for CHF. The results not only detailed commonly used Chinese herbs, Chinese patent medicines and traditional prescriptions but also analysed the efficacy and safety of TCM-WM therapy for CHF. The research showed that, in general, the efficacy and safety of the Chinese medicines were both satisfactory. Most side effects could be tolerated, and some patients recovered easily as a result of symptomatic treatment. We also found that TCM-WM therapy could significantly improve the clinical effectiveness and reduce some adverse reactions originating from western medicines used alone (listed in table 4).

In 2000, the USA, China, Australia and Thailand jointly carried out an international cooperation to investigate the prevalence and distributing features of Asian cardiovascular disease. A total of 15 518 adults were surveyed. The prevalence of CHF was 0.9%, and the rate increased substantially with ageing in China.7 To solve the problem in China, the major treatments for CHF were Chinese medicines and Western medicines used respectively or used together.

Currently, in China the application of western medicines for CHF mainly followed the guidelines of ESC8, ACC/AHA1 and the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of CHF in 20079made by the Chinese medical association. These guidelines recommended the combination of cardiotonic, diuretics and vasodilators.

Treatment with Chinese medicines for CHF can be traced back to 1000 years ago. The earliest records on prevention and treatment for CHF were found in the book written by Sun Simiao, a well-known ancient Chinese doctor.10 With time, TCMs have accumulated a wealth of experience to treat CHF. Many well-known classic prescriptions (listed in table 2) with the advantages of significant efficacy and fewer adverse reactions have been used to date. Also, Chinese patent medicines (listed in table 1) manufactured using modern pharmaceutical technology now apply widely as guaranteed safety, effectiveness and controllable quality. According to TCM theory, the commonly used Chinese medicines (single Chinese herb, Chinese patent medicines and traditional prescriptions) for CHF have effects that are beneficial for vital energy, promoting blood flow and reducing water retention.11

Currently in China, TCM-WM therapy for CHF is very popular. Four hundred and forty-two studies (64.62%) of the 684 RCTs used TCM-WM therapy in a treatment group. As for the principles of prescription compatibility based on TCM theory, the purpose of the TCM-WM therapy is also to maximise the advantages of the two kinds of therapies and reduce the incidence of adverse reactions.

This study has also analysed the controversial issue of adverse reactions in Chinese medicines. Chinese medicine injection applied in five of the 14 studies with Chinese medicine intervention used alone, which reported the side effects. Studies have shown that the incidence of adverse reactions to Chinese medicine injections will increase compared with oral preparations due to factors such as preparation process, transport and storage.12 Another major factor for the occurrence of adverse reaction is ignoring the drug's instructions.13 Some ingredients found in Chinese herbal medicines were proved to be toxic. Therefore it was required reasonable compatibility to reduce the toxicity and adverse reactions. Taking Fuzi (Radix Aconiti Lateralis Preparata) as an example, its main ingredient is aconite alkaloids, whose effects include improving the myocardial contraction, dilation of blood vessels and increasing the blood flow. It is commonly used in the treatment for CHF such as the classic prescription Zhenwu Decoction and the Chinese patent medicine Shenfu injection. However, sometimes Fuzi may cause side effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or arrhythmia. The toxicity may decrease through reasonable prescription compatibility and application. Our study indicated that the adverse reactions of Chinese medicines used alone recovered easily through short-term withdrawal or simply symptomatic treatment.

In the ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines, commonly used medicines included diuretics (IA), ACEI (IA), β-blockers (IA), digitalis (IIa, A) and so on. However, significant efficacy accompanied adverse reactions, especially in long-term use. The usual adverse reactions of digitalis were arrhythmia, gastrointestinal symptom (anorexia, nausea, vomiting) and nervous psychiatric symptoms (impairment of vision, disorientation, confusion). The Writing Committee of ACC/AHA changed the level of recommendation for digitalis glycosides from Class I to Class IIa, having considered the risk/benefit ratio.1 As one of the most popular medicines for CHF, the common adverse reaction of ACEI was dry cough, which became the reason for withdrawal. These side effects could be seen in the control group of RCTs with conventional western medicine intervention (listed in table 4). The incidence of the above adverse reactions decreased significantly after the Chinese medicines were added to the treatment group. This suggested that the therapy of TCM-WM under the principles of compatibility could reduce the occurrence of side effects.

Modern pharmacology research has provided limited evidence for the rationality of the clinical use of TCMs. It mainly focused on a few commonly used herbs. Several reports suggest that Huangqi extract (astragalus polysaccharides) can alleviate myocardial reperfusion injury.14 Also, purified Danshen (Radix Salviae Miltiorrhiae) extract has cardioprotective effects, which, at lower doses, could alleviate ischaemia-reperfusion injury.15 Tinglizi (Semen Lepidii) can decrease the total collagen content of the ventricle and attenuate ventricular remodelling induced by abdominal aortic banding.16 17 Modern pharmacological studies have shown that most of the herbs for CHF are able to improve heart function and promote blood circulation and diuresis.18

The quality of the methodology of the literatures included in our study was not high, and this affected the reliability of our results. In order to produce scientific evidence for the efficacy and safety of TCMs, high-quality clinical studies are needed. On the other hand, basic research is also important, to reveal the material basis and mechanisms of Chinese medicines by using modern drug research technologies including phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, molecular biology, cell biology and metabonomics.

Footnotes

Funding: This review was carried out in the framework of joint Sino-Italian Laboratory; National Key Technologies R&D Programme (2004BA716B01); Italian Ministry of Health, finalised research ex art; 12 d.lgs 229/99 (6 C I 2); The International Cooperative Project of the Science and Technology Ministry (2008DFB30070).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update: chronic heart failure in the adult. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1119–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation 2008:e86–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner H. Multitarget therapy—the future of treatment for more than just functional dyspepsia. Phytomedicine 2006;13:122–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Wu G, Li S, et al. Shengmai (a traditional Chinese herbal medicine) for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD005052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu X, Song J, Lu X. A systematic assessment on clinical controlled trial of Zhenwu Decoction and its modified prescriptions in treating heart failure. Tianjin J Tradit Chin Med 2008;25:477–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mudd JO, Kass DA. Tackling heart failure in the twenty-first century. Nature 2008;451:919–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu D, Huang G, He J, et al. Investigation of prevalence and distributing feature of chronic heart failure in Chinese adult population. Chin J Cardiol 2003;1:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swedberg K, Cleland J, Dargie H, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: full text (update 2005). Eur Heart J 2005:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma A, Liu Z, Zhu W, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure in 2007. Chin J Cardiol 2007;12:1076–95. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y. Standardized research on the name of diseases of traditional Chinese medicine. Beijing: Ancient Books Publishing House of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2002:30–1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang Y, Chen L. Study on traditional Chinese medicine for cardiac failure. J Tradit Chin Med 2003;44:384–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Yi Z. Research on the issues of development and security of TCM injection. Chin Trad Herb Drugs 2009;40:1162–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li T, Ma J, Zhou Y. Investigation of clinical practice and side effects of Shenfu injection. Chin J Evid-based Med 2009;9:319–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu H, Chen L, Zhu L. Effect of Astragalus polysaccharides on expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells after hypoxia and reoxygenation. Liaoning Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2008;35:293–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang PN, Mao JC, Huang SH, et al. Analysis of cardioprotective effects using purified Salvia miltiorrhiza extract on isolated rat hearts. J Pharm Sci 2006;101:245–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo J, Chen C, Gu W, et al. Influence of Tinglizi on collagen volume fraction and perivascular collagen area in left ventricle tissue of cardiac hypertrophy induced by abdominal aortic banding in rats (In Chinese) Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2008;33:284–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo J, Chen C. Influence of Tinglizi on some neuroendocrine factors and typeIand III collagen in ventricular remodelling induced by abdominal aortic banding in rats. Zhong Yao Cai 2007;30:963–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou J. Pharmacology of traditional Chinese herbs. Beiing: China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2002. [Google Scholar]