Abstract

Biomarkers are needed to guide treatment decisions for patients with rheumatic diseases. Although the phenotypic and functional analysis of immune cells is an appealing strategy for understanding immune-mediated disease processes, immune cell profiling currently has no role in clinical rheumatology. New technologies, including mass cytometry, gene expression profiling by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and multiplexed functional assays, enable the analysis of immune cell function with unprecedented detail and promise not only a deeper understanding of pathogenesis, but also the discovery of novel biomarkers. The large and complex data sets generated by these technologies—big data—require specialized approaches for analysis and visualization of results. Standardization of assays and definition of the range of normal values are additional challenges when translating these novel approaches into clinical practice. In this Review, we discuss technological advances in the high-dimensional analysis of immune cells and consider how these developments might support the discovery of predictive biomarkers to benefit the practice of rheumatology and improve patient care.

Introduction

Commonly in rheumatology practice, therapeutic decisions need to be made in situations of uncertainty. Even for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a well-defined rheumatic disease with established treatment protocols, the optimal treatment strategy after a patient has failed first-line therapy with methotrexate (Box 1) is uncertain. Currently, we cannot predict whether this patient is most likely to respond to inhibition of TNF or IL-6, to B-cell depletion, to T-cell co-stimulatory blockade or any other pharmacological intervention. A different type of uncertainty is encountered in the setting of a poorly defined inflammatory condition (Box 2), for which data from randomized controlled clinical trials are lacking and expert opinions diverge. In both clinical scenarios, biomarkers would help in choosing the most appropriate treatment strategy. This Review focuses on the development of cellular biomarkers in rheumatic diseases. We discuss technological advances for the multidimensional profiling of immune cells and consider their utility as discovery tools and their potential use in clinical practice.

Box 1. Clinical scenario 1.

A 40 year-old female presents to the rheumatology clinic with persistent and painful swelling of her wrists and fingers for the past 2 months. She has morning stiffness lasting up to 3 h. Physical examination indicates synovitis in both wrists, 3 metacarpophalangeal and 4 proximal interphalangeal joints, and she tests positive for ACPA. The patient is started on methotrexate for a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, yet her disease remains clinically active after 3 months of therapy. What is the optimal treatment for her now?

Abbreviation: ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibody.

Box 2. Clinical scenario 2.

A 60 year-old female is admitted to the hospital with recent-onset shortness of breath. Pulmonary embolism and cardiac dysfunction are ruled out. A CT scan of her chest reveals ground glass opacities, and a lung wedge biopsy demonstrates organizing pneumonitis without evidence of granulomas, necrosis, vasculitis or malignancy. Work-up for infectious aetiologies is negative. Additional disease manifestations include arthralgias, a history of Raynaud phenomenon and a recent episode of uveitis. Stigmata of systemic sclerosis or dermatomyositis are absent, and the patient tests negative for a panel of autoantibodies. How should this patient be treated?

Biomarkers, defined as a “characteristic that can be objectively measured as an indicator of normal or pathological biological processes, or as an indicator of response to therapy”,1 can be derived from different types of data, including genetic polymorphisms, autoantibody profiles, cytokine levels or clinical parameters (Box 3).2 In immune-mediated diseases, immune cells are particularly promising from the biomarker perspective owing to their central role both as orchestrators of immune responses and as drug targets. Moreover, immune cells might not only provide information about the status quo of an immune response, but also about its history (for example, by measuring the frequency and specificity of memory T cells) and potentially about its future (for example, by measuring cellular responses to in vitro stimulation). Other medical specialties, most notably haematology, oncology and transplantation medicine, have already demonstrated the broader utility of this approach. For example, flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood, lymph node and bone marrow (Box 4) is routinely used to search for abnormal cell populations that are indicative of lymphoproliferative disorders,3 recipients of bone marrow grafts are monitored by flow cytometry for engraftment and immune reconstitution, and commercial assays are available to screen heart transplant recipients for evidence of rejection by analysing peripheral blood cells.4 ‘Personalized medicine’ and ‘precision medicine’5,6 are concepts that emphasize the need to tailor therapies according to insight into the genetic, cellular and molecular basis of the disease in each individual patient. We are optimistic that this strategy can be implemented successfully to improve outcomes for patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases and guide treatment decisions in situations of uncertainty.

Box 3. Biomarker categories.

By parameter

Genetic: germline DNA variations including single nucleotide polymorphisms and allelic variants

Biochemical: quantitative and qualitative measurements of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, salts, metabolites, etc.

Cellular: morphological and functional parameters of cells

Histopathological: properties of cells in the context of a tissue

Clinical: patient-reported data (questionnaires), physical examination

Imaging: X-ray, CT, MRI, ultrasound, nuclear imaging

By clinical utility

Diagnostic: support the diagnosis of the illness

Prognostic: forecast the natural course of the illness

Predictive: forecast the response to therapy

Pharmacodynamic: monitor drug therapy

By disease process

Descriptive: associated with the disease process, but not central to pathogenesis

Mechanistic: directly involved in pathogenesis

Box 4. Analysis of peripheral blood versus target organ.

The question of what constitutes a ‘relevant tissue’ is critical when analysing immune responses in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases.102 One perspective is that the analysis of tissues from diseased target organs, such as the synovial membrane of patients with RA, is indispensable.103 Supporting this view, multiple studies have demonstrated phenotypic differences of lymphocytes isolated from peripheral blood compared with those from the inflamed synovium of patients with RA. Furthermore, in some organs, long-lived tissue-resident immune cells have distinct functions during physiological and pathological immune responses (for example, subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in human skin).104,105 In mice, IL-23R+CD3+CD4−CD8− T cells in the entheses and the aortic root were shown to mediate the development of enthesitis, arthritis and aortitis in response to systemic overexpression of IL-23.106

Although these studies emphasize the importance of analysing target tissues in order to understand pathogenesis, obtaining specimens from affected organs is often difficult. Skin biopsies are readily performed and synovial biopsies have become more feasible with the development of ultrasound-guided minimally-invasive techniques,107,108 but kidney, lung or brain biopsies have a substantial procedural risk. Moreover, specimens are typically small and tissue preparation for single-cell analysis is challenging. Because of these limitations, peripheral blood is likely to remain as the primary source for analysing immune cells in clinical practice. Peripheral blood is easily accessible and provides enough material for analysis (10–15 × 106 mononuclear cells per 10 ml blood). Peripheral blood can be analysed repeatedly, and the comparison of samples from patients, regardless of which organs are affected by the disease, is possible.

Abbreviations: IL-23R, IL-23 receptor; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

High-resolution marker analysis

Flow cytometry

Fluorescence-based flow cytometry (Figure 1a) was introduced approximately four decades ago and has been a useful tool for the phenotypic characterization and functional analysis of immune cell subsets. Progress in dye chemistry as well as laser and cytometer technology has resulted in a steady increase in the number of parameters that can be measured per cell (Figure 2), and many modern laboratories routinely perform 10-parameter flow cytometry (forward and side scatter plus eight fluorescent channels). Whereas early flow cytometry was confined to the analysis of cell surface markers, subsequent technical advances substantially expanded the spectrum of information that can be obtained: cell membrane permeabilization enables antibody-mediated staining of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins, including cytokines and transcription factors;7 proximal cell signalling responses can be measured using antibodies that are specific for phosphorylated signalling molecules;8 cell proliferation can be quantified by tracking the dilution of a fluorescent label during successive rounds of division;9 and cells can be sorted for in vitro gene expression or functional analysis.

Figure 1.

Cellular immunophenotyping by multiparameter single-cell analysis. a | Fluorescence-based flow cytometry. Cells are stained with monoclonal antibodies conjugated to various fluorescent dyes. A stream of single cells is guided through a beam of monochromatic laser light, exciting the dye molecules to emit a characteristic spectrum of less energetic photons with longer wavelengths. Mirrors and filters direct the emitted light to photomultiplier tubes for quantification. Scattered laser light provides additional information about cell size and granularity that permits discrimination of the major subsets of lymphocytes, monocytes and granulocytes. The emission spectra of fluorophores overlap; therefore, signals from one fluorophore might be detected by more than one channel. This problem can be partially corrected by compensation, but ultimately limits the number of parameters measurable per cell. b | Mass cytometry. Cells are labelled with antibodies conjugated to rare earth metals not present in biological specimens. Individual cells are vaporized and ionized by an ICP torch. The resulting ion cloud is passed into a mass spectrometer to detect and quantify antibody-derived metal isotopes. Mass cytometry does not require compensation due to distinct mass peaks of the metal isotopes. Abbreviations: Cy, cyanine; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; ICP, inductively coupled plasma; MS, mass spectrometer; PE, phycoerythrin; PerCp, peridinin chlorophyll.

Figure 2.

Timeline of technical advances. Advances in flow cytometry and gene expression analysis since 1969. Abbreviations: CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; mAb, monoclonal antibody; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing.

Key points.

Immune cell profiling to provide prognostic information and predict treatment responses is not yet part of clinical rheumatology practice

Novel technologies, including mass cytometry, RNA-seq and multiplexed functional assays, promise insight into the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases with unprecedented detail and might lead to the discovery of new biomarkers

Computational and statistical approaches for managing and analysing big data need to be refined to achieve the full potential of these assays

Assay standardization and the definition of normal values are prerequisites for the introduction of high-dimensional cytometry, genome-wide gene expression analysis and multiplexed functional assays into clinical practice

Immune cell profiling has the potential to improve outcomes in rheumatic diseases by providing mechanistic insight into the disease process in individual patients and guiding treatment decisions

The study of patients with RA provides some examples of how flow cytometry of immune cells isolated from blood has identified cellular parameters that might predict therapeutic responses. Given the association of RA with particular MHC II alleles, most notably HLA-DRB1*0401,10,11 much attention has focused on the analysis of CD4+ T cells. Early studies of peripheral blood cells in patients with active RA detected an increased frequency of CD4+ T cells that were positive for activation-induced surface markers, including CD69, HLA-DR, CD49a (very late antigen 1), and CD154.12–14 Several groups have since described the expansion of IL-17-producing helper T cells (TH17 cells) relative to regulatory T (TREG) cells in patients with active disease.15,16 Although no consensus has emerged as to whether the phenotype or function of TREG cells is altered in RA (recently reviewed elsewhere17), IL-6 receptor blockade has been shown to result in the normalization of the TH17-cell to TREG-cell ratio.18–20 Another T-cell abnormality in RA is the expansion of terminally differentiated, cytotoxic CD4+CD28− T cells,21,22 particularly in patients with severe disease and extra-articular manifestations of disease.23 Small studies have reported that a positive response to treatment with abatacept or infliximab correlated with a reduction in the frequency of circulating CD4+CD28− T cells, and that a high frequency of CD4+CD28− T cells prior to initiation of abatacept therapy was associated with a poor clinical response.24,25

The enumeration of CD19+ cells in the peripheral blood, as a means of monitoring B-cell depletion in patients with RA who were treated with rituximab, might be the only routine application of flow cytometry in current rheumatology practice. Residual circulating B cells, despite rituximab therapy, have been shown to be predictive of a worse response to therapy, although this finding was not consistent between studies.26,27 Low numbers of circulating CD27+ memory B cells and CD27hiCD38hi preplasma cells at baseline have been associated with a better clinical response to rituximab,28,29 whereas a high frequency of CD27+ memory B cells has been correlated with a favourable response to TNF inhibition. 30 Whether this dichotomy can be translated into improved clinical outcomes is not known. Clearly, the validation of cellular biomarkers in prospective clinical trials still has a long way to go.31

Tetramers

Most flow cytometry studies of immune cells in RA and other rheumatic diseases have focused on major cell populations, regardless of antigen specificity. It is conceivable, however, that altered patterns of major cell subsets mostly represent secondary effects and that the quantification and functional characterization of antigen-specific cells would be more informative. Tetramer technology has enabled the identification of individual antigen-specific lymphocytes in primary cell isolates without the need for antigenic stimulation in vitro. MHC tetramers are composed of four biotinylated MHC complexes held together by an avidin anchor.32 Staining lymphocytes with fluorescently labelled MHC tetramers loaded with a peptide of interest enables the identification of T cells carrying cognate T-cell receptors (TCRs) for this MHC–peptide complex. Tetramers of the RA-associated DRB1*0401 chain loaded with citrullinated peptides derived from vimentin, aggrecan, fibrinogen, enolase and other proteins have been used to identify citrullinated-peptide-specific CD4+ T cells;33–35 whereas these cells were detected both in patients with RA and in healthy individuals, they were more numerous in patients with RA, with the greatest differences detected within the first 5 years of diagnosis. 35 Higher numbers of citrullinated-peptide-specific CD4+ T cells correlated with increased disease activity,34 whereas fewer cells were detected in patients responding to biologic therapy.35 Factors limiting the broad application of tetramer technology include the high MHC diversity in human populations (although this might be less of a problem in diseases with strong MHC association, such as RA) and the nontrivial problem of identifying relevant antigenic peptides for loading into MHC tetramers. In the aforementioned studies of citrullinated-peptide-specific T cells in RA, a candidate protein approach was used, in combination with bioinformatics, to identify protein fragments that bind to DRB1*0401. Tetramers can also be constructed from whole proteins to enable the detection of antigen-specific B cells by flow cytometry; 36 to date, no published studies have used this approach to quantify or isolate antigen-specific B cells from patients with rheumatic diseases.

Mass cytometry

As an alternative strategy, also applicable to non-autoimmune diseases, the comprehensive analysis of lymphocyte and myeloid-cell alterations using a broad range of markers of differentiation and function might identify patterns of pathological immune deviation or disease-specific subpopulations with predictive or prognostic value. The latest flow cytometers, equipped with four lasers, can detect as many as 20 parameters per cell,37 but >50 parameters per cell can be measured using mass cytometry, a powerful, new technology for high-dimensional cellular marker analyses. With this technology, cells are labelled with antibodies conjugated to rare earth metals and then analysed by mass spectroscopy (Figure 1b).38 The fluorophores used in traditional flow cytometry have broad overlapping emission profiles, which limits the number of measurable parameters, and ‘compensation’ is needed to account for the signal spillover between channels (Figure 1a). By contrast, mass cytometry relies on the detection of discretely quantized atomic masses (Figure 1b); as a result, the overlap between ‘channels’ is lower and the need for compensation reduced. Instead, the limiting factor is the availability of pure and stable metal isotopes that can be conjugated to antibodies. The greater number of parameters per cell that can be measured by mass cytometry comes at a cost: the analytical event rate is substantially lower than in fluorescence-based flow cytometry, the turbulence of nebulization results in the loss of nearly half of the input cells, and the cells are destroyed in the detection process, making cell-sorting impossible.39 Despite these limitations, mass cytometry has great promise for the field of immunology as it captures biological complexity in great detail. Applications published to date include the identification and characterization of relevant subsets in heterogeneous cell populations,40 the multi dimensional functional profiling of individual cells41 and the delineation of developmental pathways.42 A study that analysed circulating immune cells from patients before and after total hip arthroplasty by mass cytometry found that signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), and NFκB phosphorylation signals in monocytes correlated with recovery from fatigue, pain and impairment after surgery.43 The application of this techno logy to the analysis of rheumatic diseases has not been reported.

Genome-wide expression analysis

The analysis of immune cells by gene expression profiling is a complementary approach to flow and mass cytometry. Transcriptomic profiling became feasible with the development of microarray technology in the late 1990s and has been highly successful in the assessment of haematological malignancies, enabling the molecular classification of lymphomas and providing prognostic value.44,45 The basic principle of cDNA microarray technology is depicted in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

Methods for genome-wide and multiparameter gene expression analysis. cDNA microarrays: sample mRNA is reverse-transcribed into fluorescently labelled cDNA, which is then hybridized to gene-specific oligonucleotide probes arrayed on a solid matrix (the ‘chip’). After complementary sequences have bound, and unbound sample is washed away, the chip is scanned. Fluorescence intensity detected at a specific location on the array provides a measurement of mRNA abundance. RNA-sequencing: RNA is reverse-transcribed into short double-stranded cDNA fragments that are sequenced using next-generation sequencers, mapped in silico to the reference genome and counted. The number of reads representing a specific mRNA corresponds to the abundance of that mRNA in the sample. nCounter® analysis system (NanoString Technologies®, USA): mRNA molecules are hybridized in solution to two sequence-specific probes per gene of interest—a capture probe that anchors the hybrids to a solid support for analysis and a reporter probe carrying a fluorescent barcode to identify the RNA. The number of hybrids with a specific barcode corresponds to the abundance of that mRNA species in the sample.

Armed with this technology, investigators have conducted genome-wide gene expression profiling of peripheral blood cells in case–control studies of many rheumatic diseases. The most convincing finding was the interferon signature in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE),46,47 which consists of a set of type I interferon-inducible genes that is highly expressed in individuals with SLE and is consistent with other lines of evidence that suggest that type I interferon has an important function in the pathogenesis of SLE.48,49 An interferon signature was also found in patients with subacute cutaneous lupus, primary Sjögren syndrome, myositis, systemic sclerosis and a subgroup of patients with RA,50 suggesting partial overlap of the pathophysiology of these rheumatic diseases.

Multiple studies have sought to identify gene expression signatures that would predict the response of patients with RA to treatment with TNF inhibitors, rituximab or tocilizumab (reviewed elsewhere51). Interestingly, two studies found (concordantly) that an interferon signature was associated with a poor response to rituximab.52,53 Results were otherwise heterogeneous, with little reproducibility between studies, probably because most of these studies were small, used diverging response criteria and differed in sample preparation and choice of microarray platform. Furthermore, the analysis of whole blood or unfractionated peripheral blood mononuclear cells is confounded by the variable abundance of neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes in samples from different individuals, which substantially affects the gene expression patterns measured in these samples.54 Many investigators have, therefore, started to analyse gene expression signatures in sorted cell subsets. For example, in their study of peripheral blood CD8+ T cells in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis and SLE, McKinney et al.55 found a gene expression signature dominated by IL-7-receptor-induced and TCR-induced genes that could be used to distinguish a subset of patients with a worse prognosis; these findings were subsequently extended to include patients with Crohn disease.56 Pratt et al.57 found a STAT3 gene expression signature in CD4+ T cells of patients with early arthritis that predicted the development of RA, particularly in anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-negative patients. Interestingly, the strength of the gene expression signature correlated with the serum concentration of IL-6, a cytokine that signals through STAT3.

Technological progress and the plummeting cost of next-generation sequencing technologies have made gene expression analysis by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) feasible (Figure 3b).58 RNA-seq has several advantages over hybridization-based microarray technology. First, sequencing itself does not depend on prior reference sequence information; as a result, RNA-seq can be used to detect variant splice isoforms and sequence variations. Furthermore, RNA-seq is more sensitive than microarray technology to rare transcripts, has a high dynamic range and is very accurate when compared with the gold standard of quantitative PCR.59 Finally, RNA-seq has the potential to provide an absolute count of transcript abundance, whereas the signal intensity of microarrays depends not only on abundance of the target sequence but also on the binding strength of the specific oligonucleotide sequence. These features of RNA-seq could help to overcome a major drawback of micro array technology—the difficulty of combining data from experiments that were performed at different times and in different laboratories thereby limiting the number of samples that could be included in a study. Genome-wide association studies have derived great strength from the analysis of very large cohorts of cases and controls that were often genotyped using different technology platforms.60 RNA-seq might be the key to analysing genome-wide gene expression profiles in similarly large cohorts.

Advances in efficient library preparation from small amounts of RNA have made RNA-seq of individual cells possible.61 Microfluidic devices can separate individual cells and automatically perform subsequent biochemical reactions in nanolitre-scale volumes, thereby enabling parallel processing of many samples and lowering the cost of consumable reagents.62 Furthermore, barcoding cDNAs from individual cells permits multiple cells to be pooled into a single sequencing reaction, thus further reducing the cost. Potential applications of single-cell sequencing include the analysis of individual rare cells (for example, antigen-specific T cells identified by MHC–peptide tetramer staining) to detect whether there is enrichment of abnormal splice variants or somatic mutations in these cells, or to analyse heterogeneous cell populations, as has been done with dendritic cells.63 Single-cell RNA-seq might complement the analysis of individual cells by high-dimensional flow or mass cytometry. RNA-seq is not limited by the availability of specific antibodies and can probe the whole transcriptome. Together, these approaches might identify candidate cell populations or functions in small cohorts of patients that could then be analysed in larger studies and, ultimately, with more readily available and less expensive technologies in the clinic. One such technology to measure the expression of multiple genes in parallel is the nCounter® analysis system (NanoString Technologies®, USA; Figure 3c),64 which enables the accurate measurement of several hundred transcripts over a large dynamic range.65

In vitro assays of immune cell function

Many in vitro assays of immune cell function exist for the measurement of cell proliferation, viability, changes in gene or protein expression, phagocytosis or cytotoxicity. Yet, functional cellular assays are mostly missing from the routine clinical laboratory. Poor reproducibility between laboratories owing to a lack of standardized protocols is a major factor contributing to this status quo. The need for more detailed reporting of experimental protocols has been recognized as a first step toward assay standardization and has led to the development of the MIATA (Minimal Information About T cell Assays) guidelines.66,67 Other hurdles for the introduction of functional assays into clinical practice include the (often substantial) degree of manual sample handling by human operators and logistical issues pertaining to sample acquisition, storage and processing. Each of these factors can introduce ‘batch effects’ and introduce day-to-day variability even within one laboratory. Nevertheless, as the clinical utility of the IFN-γ-release assay (IGRA) demonstrates, these obstacles are not insurmountable. Approximately a decade ago, the IGRA was introduced to identify patients infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis; its two variants (Figure 4a), an ELISPOT assay68 (marketed as T-SPOT®.TB, Immunotec, UK) and an ELISA-based method (marketed as QuantiFERON®–TB Gold, Quest Diagnostics, USA),69 are now established in the clinic.

Figure 4.

In vitro assays of cell function. a | Mycobacterium tuberculosis IFN-γ-release assay. In the ELISA method (marketed as QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube Test; Quest Diagnostics, USA), whole blood is stimulated with M. tuberculosis proteins, and the amount of IFN-γ secreted into the supernatant is quantified by ELISA.69 In the ELISPOT method (marketed as T-SPOT.TB; Oxford Immunotec, UK),68 PBMCs are prepared by density gradient centrifugation. A defined number of cells is then stimulated with M. tuberculosis protein for 24h on plates coated with anti-IFN-γ antibodies. Antigen-responsive cells secrete IFN-γ, which binds to these antibodies and is, after removal of the cells, subsequently detected by a second labelled anti-IFN-γ antibody. The number of spots on the plate corresponds to the number of IFN-γ+ cells in the sample. b | Whole blood multiparameter stimulation assay.70 Whole blood is added to a battery of TruCulture® tubes (Myriad RBM, USA) prefilled with standardized amounts of individual stimuli. The tubes are incubated on a simple heating block. After 24h, the supernatant is separated from the cells by centrifugation and analytes of interest are measured in the supernatant using a bead-based multiplex ELISA. The number of data points generated per sample is equal to the number of stimuli multiplied by the number of analytes measured in the supernatant. Abbreviations: ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked Immunospot; M.tb., Mycobacterium tuberculosis; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; RBC, red blood cell.

A conceptually different approach, taken by Duffy et al.,70 was the stimulation of whole blood with a panel of 27 stimuli followed by measuring the secretion of 32 analytes using a multiplex bead immunoassay. Rather than looking at antigen-specific responses, this study focused on nonspecific stimulation with ligands of microbial origin, cytokines or a combination of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies as a polyclonal T-cell stimulus. Minimal sample handling was required owing to the use of a novel semi-closed culture system (Figure 4b). The 25 healthy volunteers recruited for this study had mostly identical responses, except for two participants whose blood cells did not secrete IL-1α in response to any of the stimuli, suggesting that this kind of immune profiling is both reliable and sensitive enough to detect aberrant responses. A drawback of the method is that bulk stimulation of whole blood activates a spectrum of cell types, each of which could contribute differentially to the global response measured. Some results might, therefore, be difficult to interpret given the lack of cell-count normalization and the inability to distinguish primary from secondary effects with a single readout after 24 h. Nonetheless, approaches like this might have utility in the clinic. The pattern of the response to antigen-specific stimulation in diseases for which candidate antigens have been identified (for example, citrullinated proteins in RA), or polyclonal stimulation in diseases without known autoimmune targets, might identify dominant pathways in individual patients, thereby providing guidance for therapeutic decisions. In the future, functional studies of this kind might use integrated microfluidic devices, a ‘lab on a chip’,71 that require little starting material and enable the automated sampling and analysis of supernatant at multiple time points.

Big data

A common theme of fluorescence-based cytometry, mass cytometry, genome-wide analysis of gene expression and multiplex functional assays is the generation of very large data sets. Transcriptomic analysis, starting with microarrays, was a pioneering technology for dealing with so-called ‘big data’ and led to the development of techniques for quality control and data normalization as well as novel methods for data analysis and visualization.72–74 One commonly used method for analysing microarray data is cluster analysis and the generation of heat maps to visualize results (Figure 5a);75 cluster analysis, for example, was used for the identification of the interferon signature in SLE. Principal component analysis (PCA)76 and similar dimensional reduction methods are other strategies to summarize microarray data and detect patterns in large data sets. These approaches enable high-dimensional data from individual samples to be plotted along 2D axes in a way that preserves the relative distance between the samples. Application of these methods often reveals relationships between subsets of samples that are not obvious to the eye.

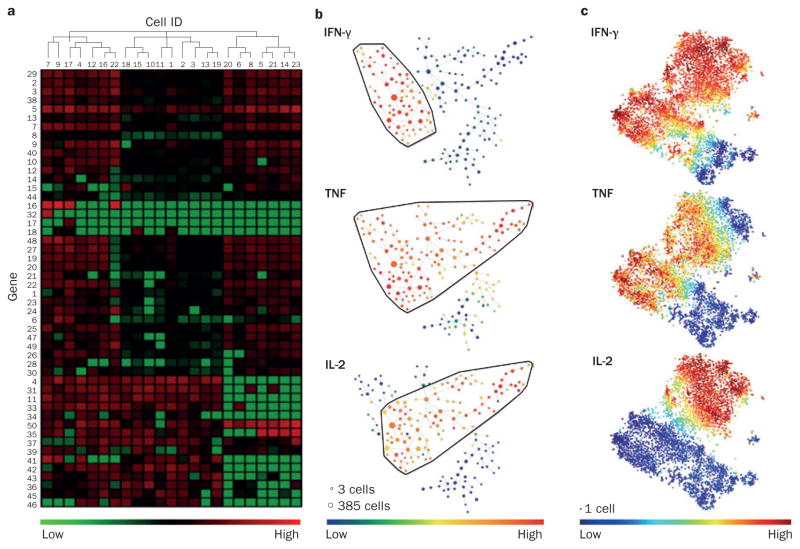

Figure 5.

Analysing and displaying large complex data sets. Human memory CD4+ T cells were stimulated for 24 h with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 beads. After 24 h of incubation, cells were either sorted for single-cell RNA-seq or analyzed by 32-parameter mass cytometry. a | Cluster analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data. 50 differentially expressed genes are depicted (green, high expression; red, low expression). A cluster algorithm has ordered cells (columns) and genes (rows) by expression, revealing shared and distinct transcriptional patterns. Cellular hierarchy is represented by a dendrogram. b | SPADE for mass cytometry data. With 32 markers, SPADE groups cells into nodes on the basis of panel-wide similarity of marker expression. Node size represents the number of cells in the cluster. Nodes are joined in a minimal-spanning tree that represents phenotypic similarity; the degree of dissimilarity between two nodes increases with the number of nodes separating them. Colour depicts expression of an individual marker across all nodes. IFN-γ, TNF and IL-2 are shown as examples. c | viSNE map for mass cytometry data. A dimensionality reduction algorithm (t-SNE) ‘projects’ the 32-parameter data set onto a 2D plane. Each dot represents an individual cell and phenotypic similarity across the marker panel is represented by distance. Colour represents expression of individual markers. Abbreviations: RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; SPADE, spanning-tree progression analysis of density-normalized events; viSNE, visualization of the t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding algorithm.

Gene expression analysis by RNA-seq poses additional analytical challenges in that substantial data processing is required to convert the massive amounts of raw data generated by automated sequencing machines into gene expression values. This process requires sophisticated data handling procedures. Next-generation sequencers generate millions of short (~100bp) reads. The first critical step in analysing RNA-seq data is the mapping of reads to specific genes using software implementations of sequence alignment algorithms.77,78 The second step is to infer expression values, which in essence means to count the number of reads per gene. Mapped reads can also be used to identify novel transcripts. The optimal strategies for RNA-seq analysis of specific applications are still being defined.79

Flow cytometry data have traditionally been analysed by manual gating of 2D dot plots. This approach is sufficient to visualize the production of two cytokines by a cell population of interest, but cannot adequately represent the data when three or more cytokines are measured simultaneously. Moreover, although biological evidence supports the use of a CD3 gate to identify T cells or a CD19 gate for B cells, for example, manual gating becomes increasingly difficult and subjective when high-dimensional data sets are analysed, data sets that might include markers expressed across a spectrum of cell types. To this end, we and others have explored the utility of automated gating methods.80–82 SPADE (Spanning-tree Progression Analysis of Density-normalized Events)83 is a radical departure from 2D gating, as cells are clustered in n-dimensional space according to similarity in expression across all n measured parameters. For data visualization, the cluster network is ‘flattened’ into a 2D dendrogram (Figure 5b). Since the introduction of SPADE, several alternative approaches have been developed for the identification of novel cellular subsets and the analysis of rare cell types, including viSNE (visualization of the t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding algorithm), which preserves individual cellular events and represents similarity across all n markers as distance between cells in a 2D plot (Figure 5c).84,85

Although many computational strategies have been developed, additional research in this area is needed. RNA-seq data analysis continues to evolve as new sequencing protocols emerge, and mass cytometry data analysis is an active area of research as investigators consider its application in disease-specific case–control studies. The large-scale application of mass cytometry will require the development of effective normalization strategies86 and of automated methods to infer and correct for variations in cell proportions in different clinical samples.87 Clearly, a paramount challenge is to translate statistical findings into biological meaning with pathway analyses, integrating with biological databases, and automated cross-referencing with biomedical context.

Translation into clinical practice

We have described existing and emerging techniques for the high-dimensional profiling of immune cells in research. By using either of two basic strategies, these investigations could enable the development of clinically useful biomarkers. The first strategy relies on data reduction and the identification (by applying appropriate filters) of a single parameter or small number of parameters that can be measured using standard techniques. The search for prognostic markers in colorectal cancer is a good example of this approach. A combination of gene expression analysis, tissue microarrays and flow cytometric profiling of colorectal cancers showed that the extent and localization of infiltrating memory T cells, in particular CD8+ T cells, correlated with a lack of early metastatic invasion and a better overall prognosis.88,89 From the initial multidimensional analysis, a simple immunohistochemical score was developed that requires detection of only three markers (CD3, CD8 and CD45R) in two regions of a tumour—a scoring system that might be implemented broadly in clinical practice.90

The second strategy involves the use of high-dimensional assays in clinical practice, as the pattern of multiple markers might be more informative than a single marker or a simple ratio between two markers. In addition to the technical issues already discussed, the implementation of this approach generates additional challenges. In a research setting, molecular and cellular analyses are typically performed at a single institution, often by a small number of technicians, and samples are batched into just a few runs. In the clinical setting, however, samples are processed in real-time on a daily basis, and the data from individual patients are compared to a historical reference. This strategy, therefore, relies on the development of robust standardized protocols for sample handling and analysis that enable reproducible results within and between institutions and a precise definition of ‘normal’. The Human Immunology Project is one effort to generate this knowledge.39

Factors contributing to variability in flow cytometry include the definition of cell subsets, choice of antibody clones and fluorochromes, cytometer settings, sample handling and analysis. Lyoplates™ (BD Biosciences, USA) contain standardized antibody mixtures that improve reproducibility of results.91 Operator training and the development of software tools for automated analysis are other strategies for improving the reliability of results. An additional problem to be solved is the interpretation of multiparametric data by medical professionals. Substantial training and learning as well as the development of appropriate clinical decision support tools will be required to empower rheumatologists to deal with big data.1

Conclusions

The clinical vignettes in Box 1 and Box 2 highlight two common situations in which uncertainty exists regarding the optimal treatment strategy for patients with a rheumatic disease. How might immune-cell profiling contribute to the management of these patients? In clinical scenario 1 (Box 1), several validated options exist for treating this patient with RA;92 yet, for any of these interventions a fraction of treated patients will have an in adequate response, either due to inter-individual differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, or because of differences in the disease process itself. Mechanistic biomarkers3 that capture the disease state in the individual patient and predict the response to therapy would be extremely useful. Potential cellular biomarkers include the frequency of immune cell subsets, their gene expression signatures, or quality and magnitude of response to antigen-specific stimulation (for example, using citrullinated peptides). The new technologies introduced in this Review might help to identify candidate biomarkers (for example, using multiparameter cytometry) or to improve the quality of existing approaches (for example, by replacing microarrays with RNA-seq).

Clinical scenario 2 (Box 2) was introduced to highlight the emerging concept that inflammatory diseases can be classified according to similarities in pathogenesis or therapeutic responsiveness.93 TNF inhibitors, as the first biologic agent in rheumatology practice, have proven their therapeutic efficacy for many diseases. However, responses diverge substantially for subsequently introduced biologic agents. For example, IL-6 blockade, although effective for treating RA or Still disease, does not work for patients with ankylosing spondylitis, and IL-1 blockade is effective in treating autoinflammatory syndromes and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, but is only marginally effective in the treatment of RA.93 The realization that rheumatic diseases do not respond uniformly to the increasing number of therapeutic options is of potential value for managing patients with rare conditions. The identification of immune signatures for clinical responsiveness to targeted therapies, as defined in randomized clinical trials of common diseases, might enable clinicians to treat patients with uncommon clinical presentations more effectively by comparing patient data to these validated immune signatures. Immune cell profiles of peripheral blood samples are probably major components of such immune signatures, together with genetic or serological markers and histopathology findings; the latter dimensions of the disease process are outside the scope of this Review. The potential of immune cell profiling for predicting therapeutic responses in rheumatic diseases has not yet been realized, but recent technological advances promise progress in the near future.

Acknowledgments

J.E. is supported by an NIH grant R03AR066357-01A1 and a Disease Targeted Research Pilot Grant from the Rheumatology Research Foundation. D.A.R. is supported by an NIH training grant T32 5T32AR007530. M.B.B. is supported by NIH grant 1UH2AR067694-01. S.R. is supported by NIH grants 1U01HG0070033, 1R01AR063759-01A1, 5U01GM092691-04, 1UH2AR067677-01, and 1R01AR065183-01.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

J.E., D.A.R. and N.C.T. researched data for the article. S.R., J.E., D.A.R. and N.C.T. substantially contributed to discussion of content and writing the manuscript. All authors contributed to review/editing of the manuscript before submission.

References

- 1.Robinson WH, et al. Mechanistic biomarkers for clinical decision making in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:267–276. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery P, Dörner T. Optimising treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a review of potential biological markers of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:2063–2070. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.148015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virgo PF, Gibbs GJ. Flow cytometry in clinical pathology. Ann Clin Biochem. 2012;49:17–28. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kittleson MM, Kobashigawa JA. Long-term care of the heart transplant recipient. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2014;19:515–524. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirnezami R, Nicholson J, Darzi A. Preparing for precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:489–491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1114866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollebecque A, Massard C, Soria JC. Implementing precision medicine initiatives in the clinic: a new paradigm in drug development. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26:340–346. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sander B, Andersson J, Andersson U. Assessment of cytokines by immunofluorescence and the paraformaldehyde-saponin procedure. Immunol Rev. 1991;119:65–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez OD, Nolan GP. Simultaneous measurement of multiple active kinase states using polychromatic flow cytometry. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:155–162. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells AD, Gudmundsdottir H, Turka LA. Following the fate of individual T cells throughout activation and clonal expansion. Signals from T cell receptor and CD28 differentially regulate the induction and duration of a proliferative response. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3173–3183. doi: 10.1172/JCI119873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregersen PK, Silver J, Winchester RJ. The shared epitope hypothesis. An approach to understanding the molecular genetics of susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1205–1213. doi: 10.1002/art.1780301102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raychaudhuri S, et al. Five amino acids in three HLA proteins explain most of the association between MHC and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:291–296. doi: 10.1038/ng.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitzalis C, Kingsley G, Murphy J, Panayi G. Abnormal distribution of the helper-inducer and suppressor-inducer T-lymphocyte subsets in the rheumatoid joint. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1987;45:252–258. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(87)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ichikawa Y, Shimizu H, Yoshida M, Arimori S. Activation antigens expressed on T-cells of the peripheral blood in Sjögren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1990;8:243–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berner B, Wolf G, Hummel KM, Müller GA, Reuss-Borst MA. Increased expression of CD40 ligand (CD154) on CD4+ T cells as a marker of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:190–195. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niu Q, Cai B, Huang ZC, Shi YY, Wang LL. Disturbed TH17/TREG balance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2731–2736. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1984-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, et al. The TH17/TREG imbalance and cytokine environment in peripheral blood of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:887–893. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooles FA, et al. TREG cells in rheumatoid arthritis: an update. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15:352. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samson M, et al. Brief report: inhibition of interleukin-6 function corrects TH17/TREG cell imbalance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2499–2503. doi: 10.1002/art.34477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pesce B, et al. Effect of interleukin-6 receptor blockade on the balance between regulatory T cells and T helper type 17 cells in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;171:237–242. doi: 10.1111/cei.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiolat A, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor blockade enhances CD39+ regulatory T cell development in rheumatoid arthritis and in experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:273–283. doi: 10.1002/art.38246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt JV, Su GH, Reddy JK, Simon MC, Bradfield CA. Characterization of a murine Ahr null allele: involvement of the Ah receptor in hepatic growth and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6731–6736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawlik A, et al. The expansion of CD4+CD28− T cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:R210–R213. doi: 10.1186/ar766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martens PB, Goronzy JJ, Schaid D, Weyand CM. Expansion of unusual CD4+ T cells in severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1106–1114. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scarsi M, Ziglioli T, Airò P. Decreased circulating CD28-negative T cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with abatacept are correlated with clinical response. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:911–916. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scarsi M, Ziglioli T, Airò P. Baseline numbers of circulating CD28-negative T cells may predict clinical response to abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2105–2111. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dass S, et al. Highly sensitive B cell analysis predicts response to rituximab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2993–2999. doi: 10.1002/art.23902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brezinschek HP, Rainer F, Brickmann K, Graninger WB. B lymphocyte-typing for prediction of clinical response to rituximab. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R161. doi: 10.1186/ar3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sellam J, et al. Blood memory B cells are disturbed and predict the response to rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3692–3701. doi: 10.1002/art.30599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vital EM, et al. Management of nonresponse to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis: predictors and outcome of re-treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1273–1279. doi: 10.1002/art.27359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daien CI, et al. High levels of memory B cells are associated with response to a first tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a longitudinal prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R95. doi: 10.1186/ar4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vital EM, Dass S, Buch MH, Rawstron AC, Emery P. An extra dose of rituximab improves clinical response in rheumatoid arthritis patients with initial incomplete B cell depletion: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204544. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Altman JD, et al. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snir O, et al. Identification and functional characterization of T cells reactive to citrullinated vimentin in HLA-DRB1*0401-positive humanized mice and rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2873–2883. doi: 10.1002/art.30445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scally SW, et al. A molecular basis for the association of the HLA-DRB1 locus, citrullination, and rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2569–2582. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James E, et al. Citrulline specific TH1 cells are increased in rheumatoid arthritis and their frequency is influenced by disease duration and therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1712–1722. doi: 10.1002/art.38637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franz B, May KF, Jr, Dranoff G, Wucherpfennig K. Ex vivo characterization and isolation of rare memory B cells with antigen tetramers. Blood. 2011;118:348–357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chattopadhyay PK, et al. Quantum dot semiconductor nanocrystals for immunophenotyping by polychromatic flow cytometry. Nat Med. 2006;12:972–977. doi: 10.1038/nm1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bendall SC, Nolan GP, Roederer M, Chattopadhyay PK. A deep profiler’s guide to cytometry. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maecker HT, McCoy JP, Nussenblatt R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the Human Immunology Project. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:191–200. doi: 10.1038/nri3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newell EW, et al. Combinatorial tetramer staining and mass cytometry analysis facilitate T-cell epitope mapping and characterization. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:623–629. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodenmiller B, et al. Multiplexed mass cytometry profiling of cellular states perturbed by small-molecule regulators. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:858–867. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bendall SC, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 2011;332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaudillière B, et al. Clinical recovery from surgery correlates with single-cell immune signatures. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:255ra131. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Golub TR, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alizadeh AA, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennett L, et al. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. J Exp Med. 2003;197:711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baechler EC, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2610–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ermann J, Bermas BL. The biology behind the new therapies for SLE. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:2113–2119. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crow MK. Type I interferon in the pathogenesis of lupus. J Immunol. 2014;192:5459–5468. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rönnblom L, Eloranta ML. The interferon signature in autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:248–253. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835c7e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burska AN, et al. Gene expression analysis in RA: towards personalized medicine. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14:93–106. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2013.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thurlings RM, et al. Relationship between the type I interferon signature and the response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3607–3614. doi: 10.1002/art.27702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raterman HG, et al. The interferon type I signature towards prediction of non-response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R95. doi: 10.1186/ar3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palmer C, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA, Brown PO. Cell-type specific gene expression profiles of leukocytes in human peripheral blood. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McKinney EF, et al. A CD8+ T cell transcription signature predicts prognosis in autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2010;16:586–591. doi: 10.1038/nm.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JC, et al. Gene expression profiling of CD8+ T cells predicts prognosis in patients with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4170–4179. doi: 10.1172/JCI59255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pratt AG, et al. A CD4 T cell gene signature for early rheumatoid arthritis implicates interleukin 6-mediated STAT3 signalling, particularly in anti-citrullinated peptide antibody-negative disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1374–1381. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Okada Y, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506:376–381. doi: 10.1038/nature12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang F, et al. mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods. 2009;6:377–382. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu AR, et al. Quantitative assessment of single-cell RNA-sequencing methods. Nat Methods. 2014;11:41–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shalek AK, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic paracrine control of cellular variation. Nature. 2014;510:363–369. doi: 10.1038/nature13437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Geiss GK, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kulkarni MM. Digital multiplexed gene expression analysis using the NanoString nCounter system. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb25b10s94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471142727.mb25b10s94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Janetzki S, et al. “MIATA”-minimal information about T cell assays. Immunity. 2009;31:527–528. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Britten CM, et al. T cell assays and MIATA: the essential minimum for maximum impact. Immunity. 2012;37:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lalvani A, et al. Rapid effector function in CD8+ memory T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mori T, et al. Specific detection of tuberculosis infection: an interferon-γ-based assay using new antigens. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:59–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-179OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duffy D, et al. Functional analysis via standardized whole-blood stimulation systems defines the boundaries of a healthy immune response to complex stimuli. Immunity. 2014;40:436–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen W, et al. Emerging microfluidic tools for functional cellular immunophenotyping: a new potential paradigm for immune status characterization. Front Oncol. 2013;3:98. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Altman RB, Raychaudhuri S. Whole-genome expression analysis: challenges beyond clustering. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:340–347. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Irizarry RA, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mootha VK, et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Raychaudhuri S, Stuart JM, Altman RB. Principal components analysis to summarize microarray experiments: application to sporulation time series. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2000;2000:455–466. doi: 10.1142/9789814447331_0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kratz A, Carninci P. The devil in the details of RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:882–884. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pyne S, et al. Automated high-dimensional flow cytometric data analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8519–8524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903028106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hu X, et al. Application of user-guided automated cytometric data analysis to large-scale immunoprofiling of invariant natural killer T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:19030–19035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318322110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aghaeepour N, et al. Critical assessment of automated flow cytometry data analysis techniques. Nat Methods. 2013;10:228–238. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Qiu P, et al. Extracting a cellular hierarchy from high-dimensional cytometry data with SPADE. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:886–891. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Amir ED, et al. viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:545–552. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shekhar K, Brodin P, Davis MM, Chakraborty AK. Automatic Classification of Cellular Expression by Nonlinear Stochastic Embedding (ACCENSE) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:202–207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321405111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Finck R, et al. Normalization of mass cytometry data with bead standards. Cytometry A. 2013;83:483–494. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bruggner RV, Bodenmiller B, Dill DL, Tibshirani RJ, Nolan GP. Automated identification of stratifying signatures in cellular subpopulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2770–E2777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408792111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pagès F, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2654–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Galon J, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Galon J, et al. Towards the introduction of the ‘Immunoscore’ in the classification of malignant tumours. J Pathol. 2014;232:199–209. doi: 10.1002/path.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nomura L, Maino VC, Maecker HT. Standardization and optimization of multiparameter intracellular cytokine staining. Cytometry A. 2008;73:984–991. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Singh PP, Smith VL, Karakousis PC, Schorey JS. Exosomes isolated from mycobacteria-infected mice or cultured macrophages can recruit and activate immune cells in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;189:777–785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schett G, Elewaut D, McInnes IB, Dayer JM, Neurath MF. How cytokine networks fuel inflammation: toward a cytokine-based disease taxonomy. Nat Med. 2013;19:822–824. doi: 10.1038/nm.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hulett HR, Bonner WA, Barrett J, Herzenberg LA. Cell sorting: automated separation of mammalian cells as a function of intracellular fluorescence. Science. 1969;166:747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3906.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Williams AF, Galfrè G, Milstein C. Analysis of cell surfaces by xenogeneic myeloma-hybrid antibodies: differentiation antigens of rat lymphocytes. Cell. 1977;12:663–673. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Parks DR, Hardy RR, Herzenberg LA. Three-color immunofluorescence analysis of mouse B-lymphocyte subpopulations. Cytometry. 1984;5:159–168. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990050210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Roederer M, et al. Heterogeneous calcium flux in peripheral T cell subsets revealed by five-color flow cytometry using log-ratio circuitry. Cytometry. 1995;21:187–196. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990210211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.De Rosa SC, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA, Roederer M. 11-color, 13-parameter flow cytometry: identification of human naive T cells by phenotype, function, and T-cell receptor diversity. Nat Med. 2001;7:245–248. doi: 10.1038/84701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Saiki RK, et al. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Heid CA, Stevens J, Livak KJ, Williams PM. Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 1996;6:986–994. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.de Hair MJ, et al. Features of the synovium of individuals at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: implications for understanding preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:513–522. doi: 10.1002/art.38273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pitzalis C, Kelly S, Humby F. New learnings on the pathophysiology of RA from synovial biopsies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:334–344. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835fd8eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhu J, et al. Immune surveillance by CD8αα+ skin-resident T cells in human herpes virus infection. Nature. 2013;497:494–497. doi: 10.1038/nature12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schlapbach C, et al. Human TH9 cells are skin-tropic and have autocrine and paracrine proinflammatory capacity. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:219ra8. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sherlock JP, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-γt+ CD3+CD4−CD8− entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1069–1076. doi: 10.1038/nm.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gerlag DM, Tak PP. How to perform and analyse synovial biopsies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kelly S, et al. Ultrasound-guided synovial biopsy: a safe, well-tolerated and reliable technique for obtaining high-quality synovial tissue from both large and small joints in early arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:611–617. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]