Abstract

Background: Participation is mostly cultural and familial based, and there is not any assessment scales for evaluating kids’ participation in Iranian context, therefore the purpose of this study was developing children’s participation assessment scale for Iranian children.

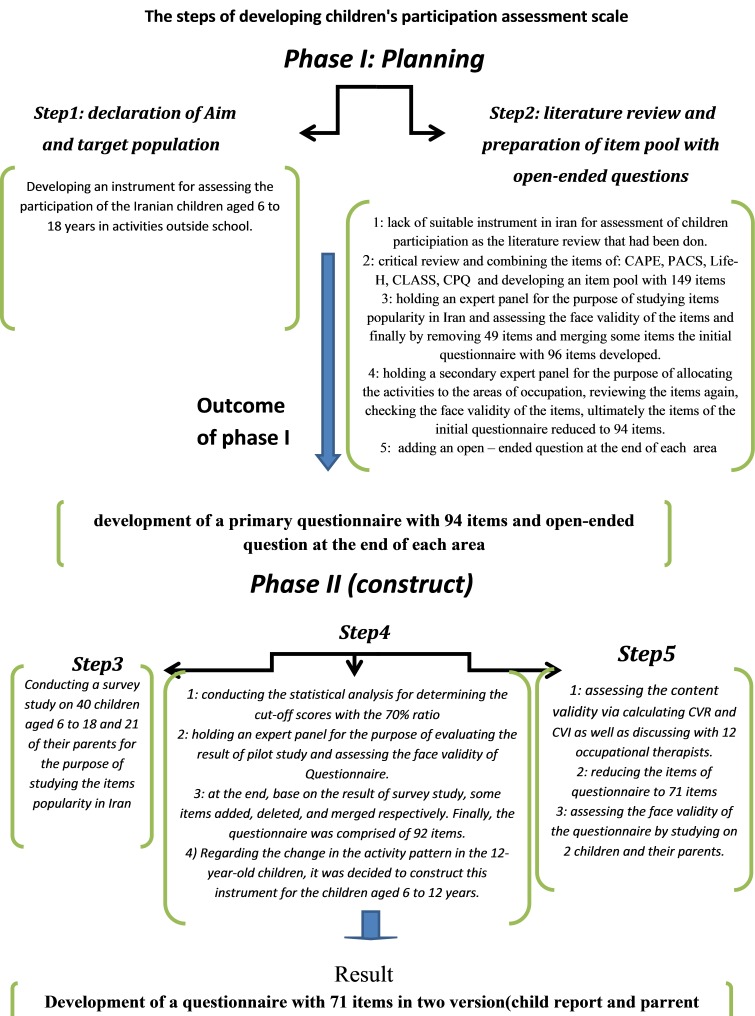

Methods: Development of this scale occurred in two phases; phase I: planning: following reviewing the literature and adopting and compiling some items of available evaluation tools in the area (such as CAPE, CPQ, CLASS, Life-H) and receiving advice from two expert panels, the preliminary94- item questionnaire was prepared. Phase II: construct: the survey study was carried out on40 children and 21 of their parents to assess the popularity of the activity in Iran; thus, the items of the questionnaire reduced to 92 and after face and content validity, the final version prepared with 71 items.

Results: The final 71-item questionnaire was developed in two parent-report and child-report versions. The 71 items based on the literature and expert panels’ advice were categorized in 8 areas of occupation according to Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (ADL, IADL, Play, leisure, social participation, education, work, and sleep/rest).

Conclusion: Iranian children’s participation assessment is a useful and culturally relevant tool to measure participation of Iranian children. It can be used in rigorous clinical and population-based research.

Keywords: Scale development, Participation, Children, Outcome measure

Introduction

Through experiences with the world around them, children mature into adults. Similarly, the experiences throughout life will lead to wisdom of older age.This experience often attains through the person’s daily activities, his/her responsibilities and roles pertaining to self-care activities, play, recreational and leisure activities, her/his education and occupation, all of which are deemed as their daily routines. Occupations result in the enhancement of experience and lead to development (1). Lack of participation or occupational deprivation affects health and wellbeing (2). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) define participation as the involvement in life situations (3).

A large proportion of children’s life belongs to the time when the school is closed and they have opportunity to participate in the world outside school. Children’s participation in the activities outside of the school can provide opportunities for the skill acquisition and role exploration and minimize the possibility of behavioral and emotional problems (4).

Since social contexts and cultural expectations shape whatever children learn and perform, they can result in different participation patterns (5,6). For instance, in 2004, Yan et al concluded a concluded that motivation of Chinese children and adolescents for participating in physical activities differed from that of American children and adolescents (7). Similarly, Engel-Yeger et al (2007) stated that culture could have a significant effect on the levels of children’s participation in the community (8,9). As another example, Larson and Verma (1999) suggested that enormous differences and variations in time use could be found among various countries (10). Based on this concept, the therapist should consider the dimensions of the participation (i.e., where and with whom the activities are done and what degrees of enjoyment are perceived as a result of performing activities and preferences) (5,11).

Facilitation of participation is regarded as the primary goal and outcome of rehabilitation; therefore, it is essential to assess and evaluate it accurately and properly using the comprehensive and appropriate instruments tailored to the specific culture. Currently, very few assessment instruments have been exclusively devised to measure participation and most of the available instruments include various dimensions and merely some part of them is devoted to the measurement of participation. In 2007, Sakzevski et al declared that the number of instruments with focus on assessing participation is very limited (12). Participation inoccupation is complicated and varies based on the time and place; consequently, its assessment is challenging (5). Presently, enormous interest in measurement of participation can be found. However, a majority of the devised instruments have been developed and validated for adults and just few of them, such as Children Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) (13,14), Pediatric Activity Card Sort (PACS) (15) and Children participation questionnaire (CPQ) (16) have been constructed for children. CAPE quantifies the participation in the activities done outside school and overlooks the rates of participation in ADL (13). CPQ has been developed for the children aged 4 to 6 years and is a parent-report instrument (16).

Although participation is considered as the final purpose of rehabilitation and a particular attention should be devoted to it as the ICF has allocated a special place for it all of the developed instruments are based on Western societies and cultures; therefore, their utility in other countries is under suspicious circumstances (17,18). Children from different societies may not have sufficient motivation to participate in the activities introduced in these instruments, or they may not have any previous experience of doing such activities (17,18). In such cases, in order to make use of proper instruments, the researchers can either develop new or translated western instruments. Although, due to the dependence of participation on culture and achieving acceptable results of participation assessment, in comparison with translating an available instrument, developing a new one may be costly and time-consuming )18). As a result, apparently, it is required to develop an instrument exclusively constructed for assessing the level of participation and for being used in a specific culture. The instruments for the participation evaluation can be a child-report or parent-report one. The parent-report instruments do not require a professional interviewer and can be utilized for all assorted communities of children with mental, physical and cognitive problems and even they are useful tools for the comparative studies among the children with various health conditions (19,20). However, the parent-report instrument cannot provide definite information about the degree of the children’s enjoyment and interest in different activities. If the instrument is child-report, it is only suitable to be applied to homogeneous groups, not to the large samples, though it can give accurate and certain responses regarding the degree of the children’s enjoyment and interest in diverse activities (20). An instrument considering both child and parent-report is a more useful instrument. Also, none of the available questionnaires has all dominants of the occupation (ADL, IADL, Play, Leisure, Social Participation, Education, Work, Sleep/Rest). Thus, the purpose of this study was to develop a child and parent-report instrument for the participation assessment with regard to the Iranian culture on the base of Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) that involves all dominants of occupation.

Methods

In order to develop this instrument, the phases of Scale Development propounded by Benson were used (21).

The procedure was done in two phases which are explained below.

Phase I: This phase is named planning. It consists of step 1 (declaration of purpose of the study and the target population), and step 2 (literature review and preparation of item pool with open-ended questions).

Phase II: This phase called construct and consists of step 3 (survey study), step 4 (statistical analysis) and step 5 (content and face validity).

Phase I: Planning

Step 1: declaration of purpose of the study and the target population: This study was designed to construct an instrument for assessing the participation of the Iranian children aged 6 to 18 years in activities outside school.

Step 2: literature review and preparation of item pool with open-ended questions: In this step, the literature reviewed in a way as follows: At first, an initial review was done to explore whether there were any reliable, valid and appropriate instruments for the participation measurement in Iran. No such instrument was found. After that, a critical review was done on available instruments of children’s participation assessment. Then, using the review of the previous studies, the items of the current instruments such as CPQ, CAPE, PACS, Life-habit, Children Leisure Assessment Scale (CLASS) were combined and merged and an item pool with an activity set of 149 items was devised. Afterwards, the expert panel was held (four PhD occupational therapists, a parent, a child psychologist and a teacher in the Center for Intellectual Development). The inclusion criteria for participants were their experience in dealing with children. The purpose of this panel was to determine the frequency of the activities in Iran and to check the face validity of the items with regard to the Iranian community. Based on the discussion occurred in this panel, 2 items were added, 49 items were excluded and 12 items were merged. As a result, an activity set with 96 items was obtained. Then, the second expert panel was held for the purpose of reviewing the items again, checking the face validity of the items and allocating the activities to the areas of occupation in (OTPF) (ADL, IADL, Play, Leisure, Social Participation, Education, Work, Sleep/Rest) (22). The experts in the panel were five occupational therapists and based on this panel, 4 activities omitted, 3 activities added, and 2 items merged and the activities were located in the areas pertaining to OTPF. Ultimately, a set of activities with 94 items was attained. OTPF is a practice framework that is published by American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). This framework provides a summary of the interdependent structures which should be greatly considered in occupational therapy. In this framework, occupation is divided into different discrete dimensions: Activity of Daily Living (ADL), Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL), Play, Leisure, Social Participation, Education, Work and Sleep / Rest (22). At the end of the list of items related to each area of OTPF, an item named “other activities” was added. This item would allow the participants to add the activities that are not mentioned in the set during the survey study (interview).

Therefore, the result of phase I was the development of a primary questionnaire (with 94 items) consisting of an activity set along with the open-ended questions.

Phase II: Construct

Step 3: survey study: In this step, a survey study was conducted on 40 children aged 6 to 18 years (average age: 11.52, SD: 2.82) using the questionnaire developed in phase I. These children were selected from all urban districts of Tehran via convenience sampling and had maximum diversity, life styles and different family education. Moreover, this study was performed on 21 parents of these children. This survey was carried out via interviewing the children and parents. They were asked to suggest any other activities they could remember. The participants were also asked to answer yes or no to the questions in the questionnaire. Sampling was done in the parks and schools. The aim of this survey was to determine the frequent activities of Iranian children.

Step 4: statistical analysis: in this step, the statistical analysis of the data obtained from the survey study was conducted in order to determine the cut-off scores. As in this type of studies the proportion ratio is between 60 to 80% (23,24), the obtained ratio accepted for including the items was 70% (i.e., 70% of the participants performed the activity)(23,24).In this stage, the expert panel was formed to evaluate the results of pilot study and discuss about the participants’ responses. In this panel, the face validity was also checked. At the end, based on the results of the pilot study, 2 activities were added, 2 activities deleted and 8 items were merged. Finally, the questionnaire was comprised of 92 items. Furthermore, regarding the change in the activity pattern in the 12-year-old children, it was decided to construct this instrument for the children aged 6 to 12 years.

Step 5: content and face validity: in this stage, the content and face validity of the questionnaire were analyzed. The content validity was examined through calculating content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) with discussing by 12 PhD occupational therapists. It led to the deletion of 21 items and the questionnaire with 71 items was prepared. In order to confirm the face validity, the experts were asked to provide their opinions regarding the face validity of the last version of the questionnaire. Additionally, two children and their parents were asked to fill out this questionnaire using self-report procedure. In this case, the questionnaires distributed between them and asked to identify the ambiguous items. The results showed that all items were clear to them and no change was applied to the appearance of the questionnaire.

The explanation of all phases is summarized in Diagram 1. For statistical analysis and determination of cut-off score, SPSS v.17 was used. For determining the content validity score, CVI and CVR was calculated.

Diagram 1 .

The steps of developing children participation assessment scale

Results

The mean ±SD age of the participants was 11.5±2.82 years (age range: 6-17 years). These participants were from the north, south, west, and east of Tehran. About 82% of them lived in an apartment and 18% lived in a house (Table 1). Items which received a score higher than 56% in CVR were included (25). The only exception was item 25 (i.e., playing with musical instruments such as flute, etc.) which had a score of 55%.However, based on the experts’ opinions, it was not omitted from the questionnaire. Based on CVI, a score higher than 79% was acceptable (25), and all 71 items of the questionnaire were above this threshold score. The data from survey were analyzed for the purpose of determining the cut-off score. The acceptable ratio for including the data was 70% (i.e., 70% of the participants perform the activity). All the including items indicated a score above 70%. The correlation between children and parents was 86 to 96%, and the mean of the correlation between the child and his/her parent was 91.6%. Based on OTPF, all the 71 items remained in this questionnaire were located in 8areas of occupation: Activities of Daily Living (ADL such as bathing), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL, such as using audio and video instruments), Play (including computer games), Leisure (like watching TV), Social Participation (such as attending a friend's birthday party), education(such as exercise classes), Work (such as doing paid work), Rest/Sleep (like knowing the rest time). Frequency of activities, with whom the activity was done, how enjoyable it is for the child to do the activity, and how much the parent is satisfied (for the parent-report version) were also reported for all the activities. Therefore, the parent-report instrument had five scales: 1) do/not to do an activity(diversity 0/1), the maximum score was 71; 2) the number of times it was done on a scale of 1 (once in the last 4 months) to 6 (every day); 3) with whom the activity was done on a scale of 1 (alone) to 5 (with others); 4) the level of enjoyment on a scale of 1 (at all) to 6 (a lot); 5) the degree of the parents’ satisfaction on a scale of 1 (dissatisfied) to 4 (much satisfaction). The child-report instrument had four scales: 1) do/not to do an activity(diversity 0/1), the maximum score will be 71; 2) the number of times on a scale of 1 (once in the last 4 months) to 6 (every day); 3) with whom the activity was done on a scale of 1 (alone) to 5 (with others); 4) the level of enjoyment on a scale of 1 (at all) to 5 (a lot). For each of these dimensions (doing or not doing the activity, the frequency of doing the activity, with whom it was done, the degree of enjoyment and parents’ satisfaction), it is feasible both to calculate the overall score and to compute 8subtotal scores (ADL, IADL, Play, Leisure, Social Participation, Work, Education, and Sleep/Rest.) (Appendix 1).

Table 1 . The frequency distribution of the demographic data .

| Variable | n | % | |

|

Education of Children |

Primary school | 28 | 75 |

| High School | 10 | 25 | |

| Dropouts | 2 | 5 | |

| Gender | Male | 21 | 52.5 |

| Female | 19 | 47.5 | |

| Residence Types | Apartment | 33 | 82 |

| House | 7 | 18 | |

| Ownership | Owner | 33 | 82 |

| Tenant | 7 | 18 | |

| Mother’s education | |||

| Illiterate | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Secondary school’s degree | 4 | 10 | |

| Diploma | 13 | 32.5 | |

| Associate's degree | 4 | 10 | |

| Bachelor | 11 | 27.5 | |

| Master’s | 4 | 10 | |

| Ph.D. | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Father’s Education | |||

| Illiterate | 2 | 5 | |

| Secondary school’s degree | 4 | 10 | |

| Diploma | 13 | 32.5 | |

| Associate's degree | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Bachelor | 12 | 30 | |

| Master’s | 5 | 12.5 | |

| PhD | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Mother’s job | |||

| Clerk | 13 | 32.5 | |

| Housewife | 27 | 67.5 | |

| Father’s job | Clerk | 18 | 45 |

| Self-employed | 17 | 42.5 | |

| Worker | 4 | 10 | |

| Others | 1 | 2.5 |

Discussion

This study introduces an instrument for measuring the participation of the children aged 6 to 12 years. Initially, the present study was designed to develop an instrument for assessing the participation of the children aged 6 to 18 years. However, based on the results obtained from the survey study, it was found that the participation pattern changed for the children above 12 years old and some activities (such as using ATM cards) were prevalent among the children above 12 years old, and some others among the children below 12 years old. This finding is in line with the Life span developmental theory proposed by Havighurst (26). This instrument was constructed based on the family-centered and child-centered approaches, and it measures the level of participation of the children according to both the children’s and their parents’ perspectives and with high content validity. In order to assessing complex and multidimensional participation dimensions, five scales were utilized: 1) do/ not to do an activity, 2) the frequency of each activity, 3) with whom it was done, 4) the level of enjoyment, 5) and the degree of the parents’ satisfaction (for the parent-report version). This instrument can be used for both homogenous and heterogeneous groups and also cover some of the subjective dimensions such as enjoyment, very well. In constructing this instrument and its framework, OTPF was used, and all areas related to the occupation (ADL, IADL, Play, Leisure, Social Participation, Education, work, Sleep/Rest) are included in this questionnaire, which is the main strengths point of this instrument in comparison with other current instruments. In fact, the weaknesses of the other instruments were attempted to be eliminated in this instrument. As an example, the CAPE instrument, which is repeatedly used in various studies, does not evaluate some areas of the occupation like ADL, Work, Sleep/Rest, and cannot be used for the children with mental problems. The other instrument is PACS which has been designed for the children aged 5 to 14 years does not include Work and Sleep areas and does not assess the participation dimensions very well (it just focus on the frequency and the diversity of the activities). Moreover, it is implemented via interviews with the child; as a result, it cannot be utilized for the children with mental problems or for the comparison of the heterogeneous groups (27). The mentioned drawbacks are eliminated in the propounded instrument by using different dimensions of the participation, adding the parent-report version and including Work and Sleep areas. Life-H does not cover some occupation areas such as Education, Work and Sleep/Rest, and does not measure the participation dimensions meticulously (28).

Conclusion

Based on what was pointed out, it can be stated that this questionnaire probably can improve the drawbacks and gaps of other available instruments and can be employed as a descriptive and evaluative questionnaire in the studies on children with and without disabilities in Iranian culture.

Limitations

There was limited access to parents with their children’s together. However this problem solved by gathering data from different places that children were available along with their parents.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a thesis (ethic code: 93/د/105/5618) written by the first author in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree in Occupational Therapy from Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Appendix

Appendix 1 . Children participation assessment scale .

| Basic activities of daily living(ADL) | CVR | R-CVI | C-CVI | S-CVI | Cutoff | ||

| 1 | Bathing in their house | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 2 | Combing | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 3 | Brushing | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 4 | Putting on and taking off the shoes | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 5 | Washing hands and face | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 6 | Choosing food over the table or tablecloth | 66% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 95 | |

| 7 | Going to the toilet in their home | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 8 | Going to the toilet in places other than their home | 83% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 92 | |

| 9 | Selecting, wearing, and taking off the upper and lower body clothes | 83% | 91% | 91% | 91% | 100 | |

| 10 | Wearing, taking off, and preserving the accessories (eyeglasses, earphones, contact lenses, etc.) | 100% | 91% | 100% | 100% | 97 | |

| 11 | Using the tableware over the table or tablecloth | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| Instrumental activates of Daily living | CVR | R-CVI | C-CVI | S-CVI | Cut off | ||

| 12 | Making Sandwiches/ mouthfuls | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 70 | |

| 13 | Using kitchen appliances for food preparation (crushing, making, and heating food) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 14 | Using Telephone/mobile at home, out of the house, and using the public phone/payphones | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 95 | |

| 15 | Using the audio and visual instruments (such as radio, television, computer, mp4, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 97 | |

| 16 | helping in preparing the meal and setting the table or tablecloth | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 92 | |

| 17 | Shopping | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 80 | |

| 18 | Using public transportation (such as taxi, bus, metro) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 80 | |

| 19 | Cleaning and organizing their rooms and personal spaces (personal wardrobes, personal drawers, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 20 | Participating in the activities associated with organizing and cleaning the house (such as dusting, sweeping using vacuum cleaner or broom) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 97 | |

| 21 | Preparing their bag for school or other classes. | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 95 | |

| Play | CVR | R-CVI | C-CVI | S-CVI | Cut off | ||

| 22 | Participating in board games (such as Mensch ärgere dich nicht, chess, card games, Mind Games , etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 23 | Jumping games (such as hopscotch, rope jumping, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 24 | Games using musical instruments (such as flute, drums, Jingle Bells, etc.) | 55% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 77 | |

| 25 | Sports and games using balls (such as football, volleyball, basketball, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 95 | |

| 26 | Racquet sports (such as table tennis, badminton, tennis, etc.) | 100% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 75 | |

| 27 | Games using skates, bicycles, and scooters. | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 28 | Ball Games (the dodgeballو etc.) | 100% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 90 | |

| 29 | Running games (a game of tag, chasing games, running, hides and seek, etc.) | 100% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 90 | |

| 30 | Playing with building toys (like puzzles , building blocks, Lego) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 31 | Playing Computer or video games (like PlayStation and x- box, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 90 | |

| 32 | Playing simulated or imaginative games (e.g., role-playing games, having the role of teachers, doctors, and aunts) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 70 | |

| 33 | Water games (swimming, dabbling, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 87 | |

| 34 | Games in the Park (such as swings, slides, see-saw, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 80 | |

| Leisure activities | CVR | R-CVI | C-CVI | S-CVI | Cut off | ||

| 35 | Going on a picnic | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 82 | |

| 36 | Going to the park and amusement parks | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 95 | |

| 37 | Going to the place of worship and going on a pilgrimage (such as a mosque, shrine, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 82 | |

| 38 | Watching TV or CD | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 97 | |

| 39 | Designing, painting, and coloring, or making crafts and artworks. | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 82 | |

| 40 | Gathering things for collections (such as coin, stamps, erasers, cards, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 41 | Letter writing (by hand on paper or electronically) | 66% | 83% | 100% | 100% | 82 | |

| 42 | Going for a walk or climbing mountains | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 43 | Non- major studies (such as newspapers, books) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 90 | |

| 44 | Engaging in favorite activities related to housekeeping | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 75 | |

| 45 | Going to the restaurants | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 97 | |

| 46 | Visiting your kin and friends | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 47 | Dancing | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 48 | Hanging out with friends | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 70 | |

| 49 | Listening to the stories | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 50 |

Participating in the artistic and cultural activities (such as ceramics and pottery, storytelling, poetry reading, calligraphy , drama, etc.) |

100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 80 | |

| Social participation | CVR | R-CVI | C-CVI | S-CVI | Cut off | ||

| 51 | Participating in a friends’ birthday party | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 92 | |

| 52 | Attending school ceremonies (Iftar, food festivals, Yalda, Secretions, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 82 | |

| 53 | Going to parties | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 54 | Sleeping in relatives’/ friends’ house | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 95 | |

| 55 | Inviting friends home | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 88 | |

| 57 | Talking on the phone to get things done (Contact schools, institutions, club, classmates, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 80 | |

| 58 | Visiting people (patients, teachers, managers, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 82 | |

| 59 | Involvement in the social institutions (public libraries, cultural centers, the Center for Intellectual Development, the local homes, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 77 | |

| 60 | Participation in extracurricular activities of the school held in groups (such as the Quran class, Song Groups, Theatre Groups, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 75 | |

| 61 | Going to the cinema | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 92 | |

| 62 | Going to live performances (including concerts, theater, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| Educational Activities | CVR | R-CVI | C-CVI | S-CVI | Cut off | ||

| 63 | Attending art classes (singing, music, drama classes, etc.) | 83% | 91% | 100% | 100% | 85 | |

| 64 | Having a private tutor (for school work, art projects, etc.) | 66% | 91% | 100% | 100% | 77 | |

| 65 | Participating in the classes other than sports and art (such as language, Quran, computers, robotics, social skills, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 80 | |

| 66 | Attending in exercise classes outside school | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 87 | |

| Work | CVR | R-CVI | C-CVI | S-CVI | Cut-off | ||

| 67 | Doing paid work | 83% | 91% | 100% | 100% | 10 | |

| 68 | Doing homework and other school assignments | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 95 | |

| Sleep/rest | CVR | R-CVI | C-CVI | S-CVI | Cut-off | ||

| 69 | Sleeping | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 | |

| 70 | Preparing for sleep (making the bed, brushing, wearing comfortable clothes, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 75 | |

| 71 | Resting (knowing the rest time, doing anything to restore the atrophied energy such as lying, showering, doing yoga, etc.) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100 |

S-CVI: Simplicity content validity index

R-CVI: Relevancy, Specificity content validity index

C-CVI: Clarity content validity index

CVR: content validity ratio

Cite this article as: Amini M, Hassani Mehraban A, Haghni H, Asgharnezhad AA, Khayatzadeh Mahani M. Development and validation of Iranian children’s participation assessment scale. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2016 (20 February). Vol. 30:333.

References

- 1.Robert K. In: Christiansen C, Baum C, Editors, Occupational development Occupational therapy: performance, participation and well-being United States of America. SLACK. 2005:43–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whiteford G. Occupational deprivation: global challenge in the new millennium. British journal of occupational therapy. 2000;63:200–204. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland 2001.

- 4.Stewart M, Reid GJ. Fostering children’s resilience. JPN. 1997;12:21–31. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(97)80018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law M. Participation in the occupations of everyday life. American journal of occupational therapy. 2002;56:640–469. doi: 10.5014/ajot.56.6.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodger S, Ziviani J. Children’s participation beyond the school grounds. Occupational therapy with children: understanding children’s occupations and enabling participation. 2006:280–294. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan J, McCuIlagh P. Cultural Influence on Youth's Motivation of Participation in Physical Activity. Journal of Sport Behavior. 2004;27(4):379–390. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel-Yeger B, Jarus T, Law M. Impact of culture on children’s community participation in Israel. American journal of occupational therapy. 2007;61:421–428. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel-Yeger B. Comparing participation patterns in out-of-school activities between Israeli Jewish and Muslim children. Scand J OccupTher. 2013;20(5):323–35. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2013.793738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson R, Verma S. How children and adolescents spend time across the world: work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychological bulletin. 1999;125:701–736. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Law L, Petrenchik T, Ziviani J, King G. In: Rodger S, Ziviani J. Ediors. Occupational therapy with children: understanding children’s occupations and enabling participation. Oxford, UK. Blackwell Ltd 2006;67-86.

- 12.Sakzevski L, Boyd R, Ziviani J. Clinimetric properties of participation measures for 5-13 year-old children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2007;49:232–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King G, Law M, King S, Hurley P, Rosenbaum P, Hanna S, et al. Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and preference for activities for children (PAC). Harcourt Assessment, Scan Antonio, TX, USA 2004.

- 14. King G, Law M, King S, Harms S, Kertoy M, Rosenbaum P. Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University, Can Child Centre for Childhood Disability Research 2004.

- 15. Mandich AD, Polatajko HJ, Miller LT, Baum C. Pediatric activity card sort (PACS). CAOT Publication ACE, Ottawa, ON, Ccanada 2004.

- 16.Rosenberg L, Jarus T, Bart O. development and initial validation of the children participation questionnaire (CPQ) Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010;32(20):1633–1644. doi: 10.3109/09638281003611086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Case-Smith J. Occupational therapy for children. Use of standardized tests in pediatric practice. Fifth ed 2005:246-275.

- 18. Willard HS, Blesedell Crepeau E, Cohn ES, Boyt Schell BA. Willard & Spackman occupational therapy, eleventh ed. Lippincoot-raven. Critiquing assessment 2009:519-536.

- 19.Coster W, Law M, Bedell G. Development of the participation and environment measure for children and youth: conceptual basis. Disability and rehabilitation. 2001:1–9. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.603017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heah T, Case T, McMuire McMuire, Law M. Successful participation: the lived experience among children with disability. Can J OccupTher. 2007;74:38–47. doi: 10.2182/cjot.06.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson J, Clark F. A guide for instrument development and validation. The American journal of occupational therpy. 1982;36(12):789–800. doi: 10.5014/ajot.36.12.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Association of Occupational Therapy. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 3rd Edition: 2014. [PubMed]

- 23.Serra-Sutton V, Ferrer M, Rajmil L, Simeoni M. Population norms and cut-off-points for suboptimal health related quality of life in two generic measures for adolescents: the Spanish VSP-A and KINDL-R. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvik A, Grøholt B. Examination of the cut-off scores determined by the Ages and Stages Questionnaire in a population-based sample of 6 month-old Norwegian infants. BMC Pediatrics. 2011;11:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jingcheng SHI, Xiankun MO, Zhenqiu SUN. Content validity index in scale development. J Cent South Univ Med Sci. 2012;37:152–155. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Havighurst RJ. Developmental tasks theory and education. New York: David Mckay; 1972.

- 27.Chien CW, Rodger S, Copley J, McLaren C. Measures of participation outcomes related to hand use for 2-12-year-old children with disabilities: a systematic review. Child: care, health and development. 2013:1–14. doi: 10.1111/cch.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris C, Kurinczuk JJ, Fitzpatrick R. Child or family assessed measures of activity performance and participation for children with cerebral palsy: a structured review. Child: care, health and development. 2005;(31,4):397–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]