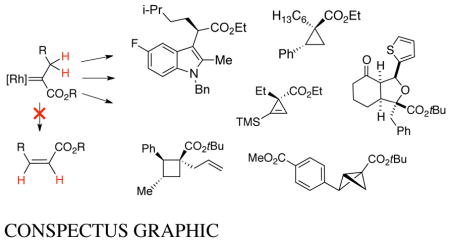

CONSPECTUS

Rh-carbenes derived from α-diazocarbonyl compounds have found broad utility across a remarkable range of reactivity, including cyclopropanation, cyclopropenation, C–H insertions, heteroatom–H insertions, and ylide forming reactions. However, in contrast to α-aryl or α-vinyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds, the utility of α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds had been moderated by the propensity of such compounds to undergo intramolecular β-hydride migration to give alkene products. Especially challenging had been intermolecular reactions involving α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds.

This account discusses the historical context and prior limitations of Rh-catalyzed reactions involving α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds. Early studies demonstrated that ligand and temperature effects could influence chemoselectivity over β-hydride migration. However, effects were modest and conflicting conclusions had been drawn about the influence of sterically demanding ligands on β-hydride migration. More recent advances have led to a more detailed understanding of the reaction conditions that can promote intermolecular reactivity in preference to β-hydride migration. In particular, the use of bulky carboxylate ligands and low reaction temperatures have been key to enabling intermolecular cyclopropenation, cyclopropanation, carbonyl ylide formation/dipolar cycloaddition, indole C–H functionalization, and intramolecular bicyclobutanation with high chemoselectivity over β-hydride migration. Cyclic α-diazocarbonyl compounds have been shown to be particularly resilient toward β-hydride migration, and are the first class of compounds that can engage in intermolecular reactivity in the presence of tertiary β-hydrogens. DFT calculations were used to propose that for cyclic α-diazocarbonyl compounds, ring constraints relieve steric interaction for intermolecular reactions, and thereby accelerate the rate of intermolecular reactivity relative to intramolecular β-hydride migration.

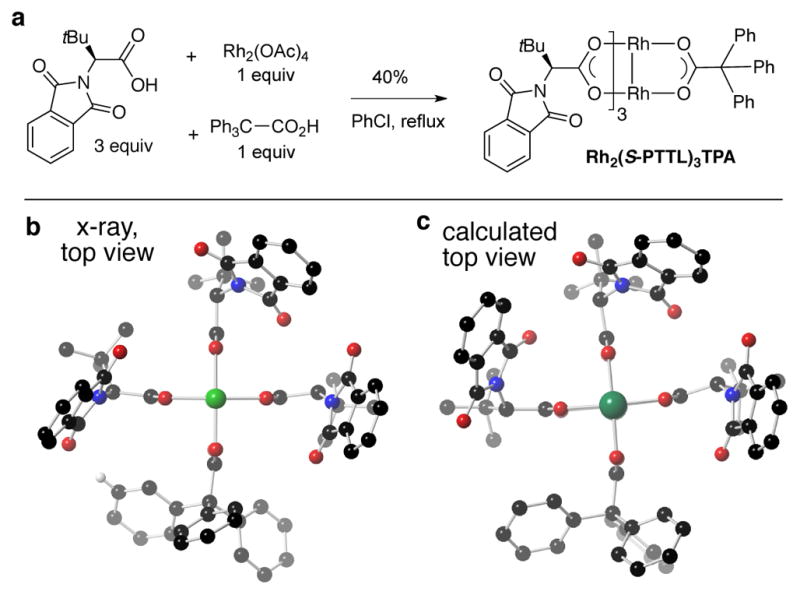

Enantioselective reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds have been developed using bimetallic N-imido-tert-leucinate-derived complexes. The most effective complexes were found by computation and X-ray crystallography to adopt a “chiral crown” conformation in which all of the imido groups are presented on one face of the paddlewheel complex in a chiral arrangement. Insight from computational studies guided the design and synthesis of a mixed ligand paddlewheel complex, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA, the structure of which bears similarity to the chiral crown complex Rh2(S-PTTL)4. Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA engages substrate classes (aliphatic alkynes, silylacetylenes, α-olefins) that are especially challenging in intermolecular reactions of α-alkyl- α-diazoesters, and catalyzes enantioselective cyclopropanation, cyclopropenation, and indole C–H functionalization with yields and enantioselectivities that are comparable or superior to Rh2(S-PTTL)4.

The work detailed in this account describes progress toward enabling a more general utility for α-alkyl-α-diazo compounds in Rh-catalyzed carbene reactions. Further studies on ligand design and synthesis will continue to broaden the scope of their selective reactions.

Introduction

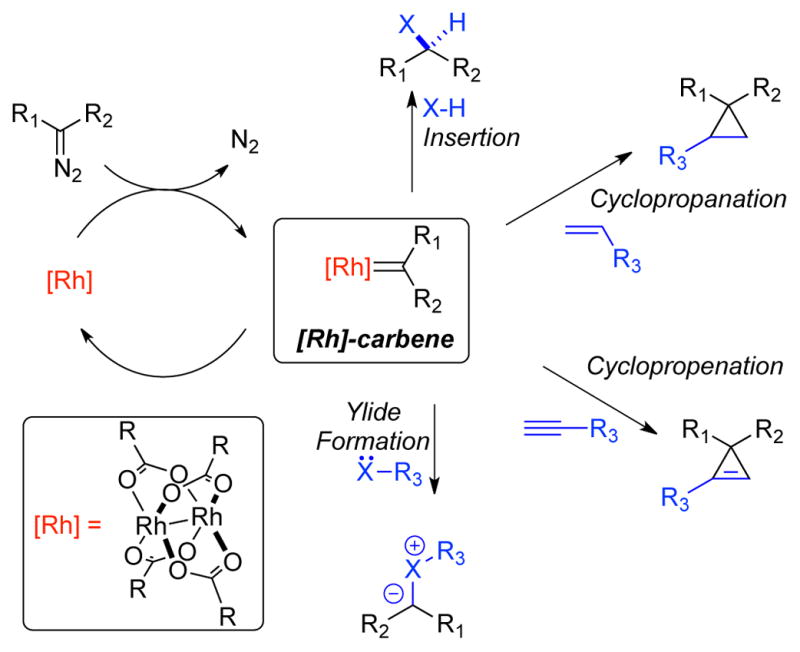

There is an ever-growing need for new chemical reactivity that can be utilized to rapidly transform simple building blocks into complex molecules in several areas of chemical research including the academic, pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and fine chemical sectors. Rh-catalyzed reactions of diazo compounds provide a powerful and versatile set of methods for C–C and C–X (X = heteroatom) bond construction, including X–H insertion reactions (where X = C, N, O, Si, S), [2+1] cycloaddition reactions (cyclopropanation, cyclopropenation), and ylide forming reactions (Scheme 1).1 The key putative intermediate in these processes is a Rh-carbene, generated from the reaction between a dirhodium(II) paddlewheel complex and a diazo compound via the loss of dinitrogen.2

Scheme 1.

Typical Rh-catalyzed reactions of α-diazocarbonyl compounds.

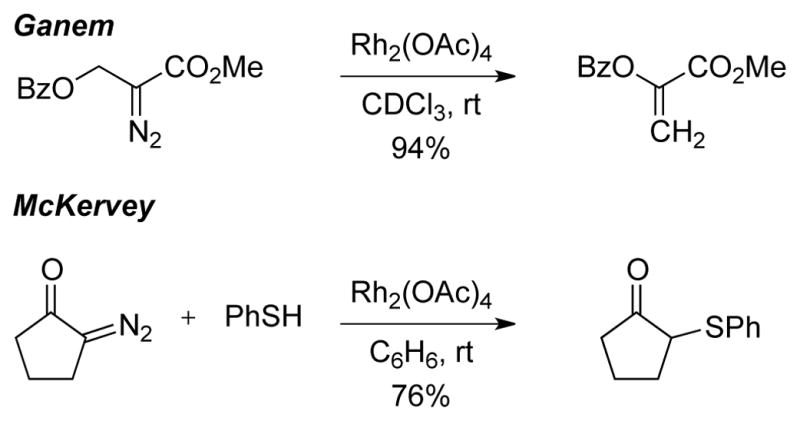

Many reactions of functionalized diazo compounds have been described. However, reactions involving simple α-alkyl-substituted α-diazo compounds had been less general. This discrepancy is primarily due to the propensity of the carbene to undergo a β-hydride migration— an olefin-forming pathway that typically precludes intermolecular reactivity (Scheme 2A). Our calculations have suggested that the mechanism of β-hydride migration is a concerted but nonsynchronous process.3 Qualitatively, the susceptibility of α-diazocarbonyl compounds (I–III) toward β-hydride migration is inversely related to β-C–H bond strength, with methine C–H bonds of III having the highest propensity for migration (Scheme 2B).

Scheme 2.

Migratory aptitude of β-C–H bonds in Rh-carbenes.

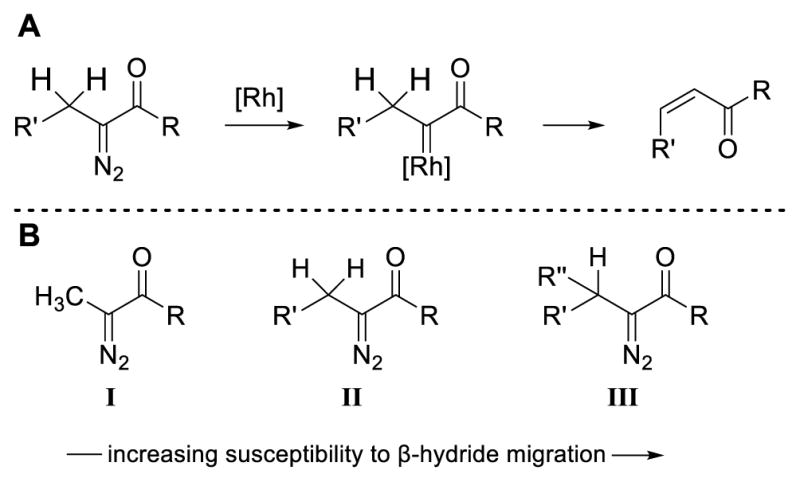

Background

In seminal work by Ganem in 1981, it was demonstrated that intramolecular benzoate migration or intramolecular cyclopropanation could outcompete β-hydride migration under Rh2(OAc)4-catalysis (Scheme 3).4a However, in cases where alternative intramolecular processes were not accessible, cis-enoates – the products of β-hydride migration – were predominantly formed. The following year, McKervey reported the seminal example of intermolecular S–H insertions of α-diazoketones with selectivity over β-hydride migration (Scheme 3).4b

Scheme 3.

First Rh-catalyzed reactions with selectivity over β-hydride migration.

Intramolecular Reactions

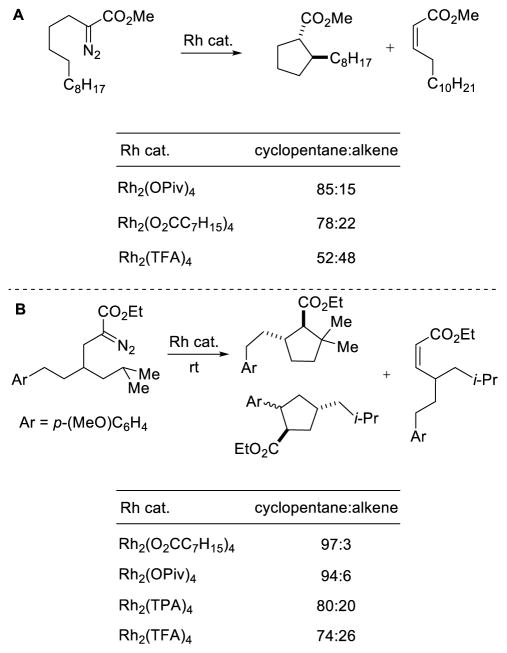

Following these early studies, examples of Rh-catalyzed reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds were reported for several intramolecular processes, with landmark contributions from the groups of Padwa and Taber.5–11 Padwa demonstrated that intramolecular carbonyl ylide formation and alkyne insertion reactions proceed in preference to β-hydride migration.6 Subsequently, Taber established that intramolecular C–H insertion can compete with β-hydride migration.9 Ligand effects were noted with respect to their ability to bias reactivity away from β-hydride migration. Selectivity for cyclopentane formation is increased from 78:22 using dirhodium tetraoctanoate to 85:15 using more sterically demanding dirhodium tetrapivalate (Scheme 4A).9a By contrast β-hydride migration was exacerbated using sterically demanding dirhodium tetratriphenylacetate (80:20) instead of dirhodium tetraoctanoate (97:3) (Scheme 4B).9c These observations led to suggestion that sterically demanding ligands promote β-hydride migration.9c As discussed below, we have shown that large carboxylate ligands in combination with low temperature can suppress β-hydride migration and favor intermolecular reactivity.

Scheme 4.

Ligand dependent chemoselectivity in Rh-catalyzed intramolecular C–H insertion.

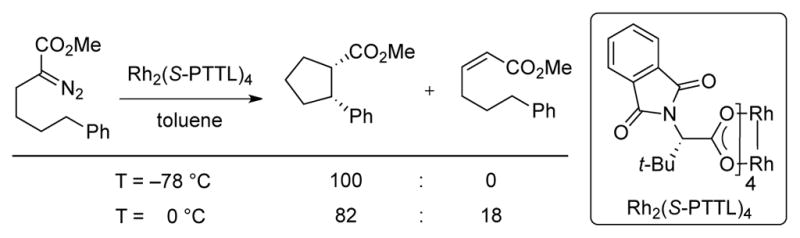

In a more recent intramolecular C–H insertion study by Hashimoto,9e an increase in selectivity over β-hydride migration was observed by running the reactions at lower temperatures (Scheme 5). At 0 °C, the ratio of cyclopentane:olefin observed was ~4:1; at –78 °C, no product of β-hydride migration was detected.

Scheme 5.

Temperature dependent chemoselectivity in Rh-catalyzed intramolecular C–H insertion.

Intermolecular Reactions

In contrast to the amount of chemoselective intramolecular Rh-catalyzed reactions reported of α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds, intermolecular reactions were primarily limited to substrates with α-methyl substitution which possess relatively strong α-C–H bonds (vide supra). Examples of intermolecular reactions with weaker C–H bonds (i.e. methylene) were comparatively rare and had been limited to insertions into heteroatom–H bonds.9d, 12–15

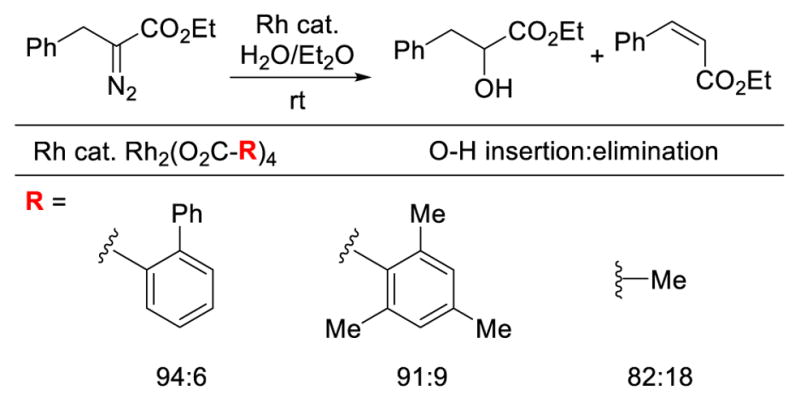

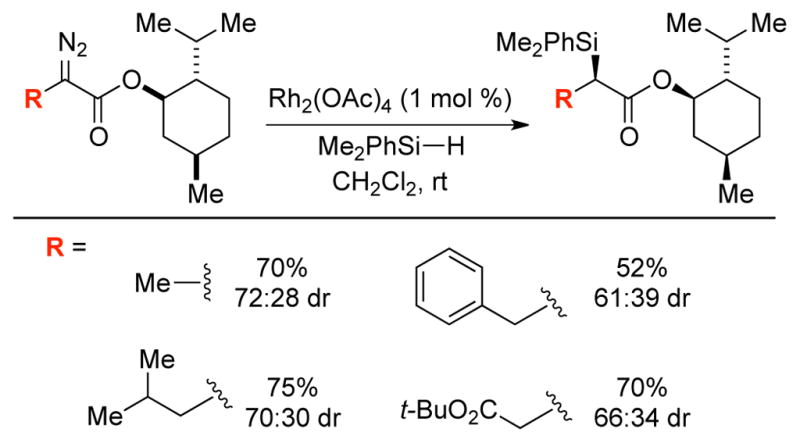

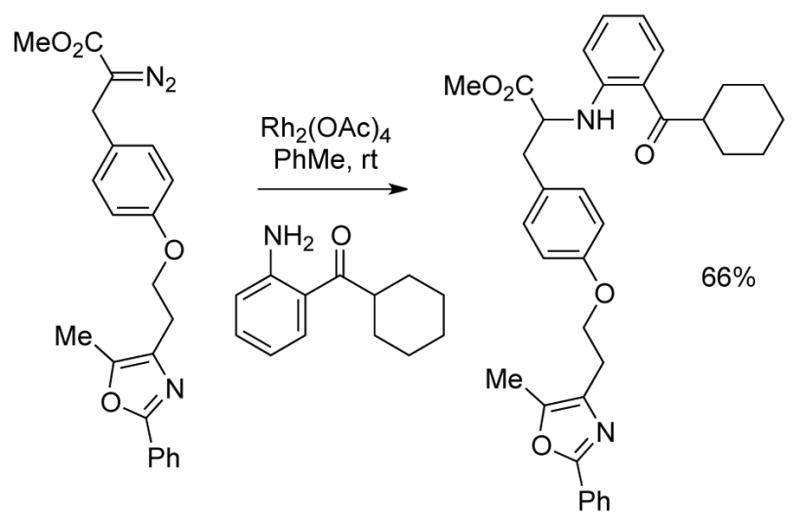

An early study by Moody revealed that ligand structure can influence selectivity over β-hydride migration relative to O–H insertion reactions of water (Scheme 6).14a Thus, the reaction of ethyl 2-diazohydrocinnamate employing Rh2(OAc)4 gave the insertion product with moderate selectivity (82:18, favoring insertion), whereas more sterically demanding catalysts featuring 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoate and o-phenylbenzoate ligands provided an increase in chemoselectivity to 91:9 and 94:6, respectively. Shortly afterwards, Landais demonstrated modest selectivity over β-hydride migration in Si–H insertion reactions with various α-alkyl substituents in the presence of Rh2(OAc)4 (Scheme 7).12a Cobb demonstrated the feasibility of intermolecular Rh-catalyzed N–H insertion reactions in an SAR study of agonists for PPARγ which has been implicated in the treatment of type 2 diabetes (Scheme 8).13

Scheme 6.

Ligand dependent chemoselectivity in Rh-catalyzed O–H insertion.

Scheme 7.

Intermolecular Rh-catalyzed Si–H insertion.

Scheme 8.

Early example of Rh-catalyzed N–H insertion.

While the studies above collectively demonstrated that ligand and temperature effects can influence chemoselectivity over β-hydride migration, the effects were modest and conflicting conclusions had been drawn about the influence of sterically demanding ligands on β-hydride migration. The ability to promote intermolecular reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds was underdeveloped and substrate specific, with only a limited appreciation of how ligand and temperature considerations could be used to bias reactions for intermolecular reactions in preference to intramolecular β-hydride migration.

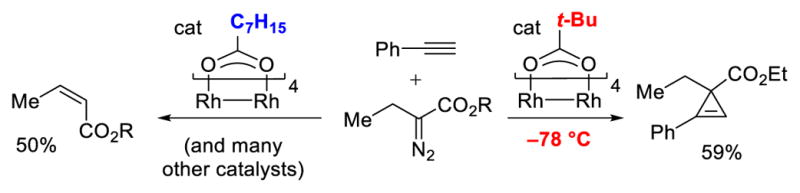

Development of General Conditions for Intermolecular Reactions

In 2007, our group reported conditions for intermolecular cyclopropenation and tandem alkyne insertion/Buchner ring expansion using α-alkyl-α-diazoesters.16 These studies represented the first general intermolecular Rh-catalyzed C–C bond forming reactions that tolerated β-hydrogens. As shown in Scheme 9, several Rh-catalysts were surveyed in the reaction of ethyl α-diazobutanoate, mostly revealing low yields of cyclopropene with significant amounts of ethyl cis-crotonate, the product of β-hydride migration. However, a dramatic chemoselectivity reversal was observed upon employing sterically demanding ligands. Additionally, low temperature proved to be vital to the suppression of β-hydride migration; the Rh2(OPiv)4-catalyzed reaction at room temperature gave 70% of cis-crotonate, while at –78 °C useful yields of cyclopropene were observed. The use of sterically demanding carboxylate ligands and low temperatures would be a recurring theme in the future development of Rh-catalyzed reactions with high selectivity over β-hydride migration (Scheme 9). A range of terminal alkynes efficiently engaged in cyclopropenation reactions with α-diazopropanoate, α-diazobutanoate, and α-diazohydrocinnamate with high selectivity over β-hydride migration (Scheme 10).

Scheme 9.

The importance of sterically demanding ligands and low temperature in intermolecular cyclopropenation reactions with α-alkyl-α-diazoesters.

Scheme 10.

Intermolecular cyclopropenation of α-diazoesters with β-hydrogens, selected examples.

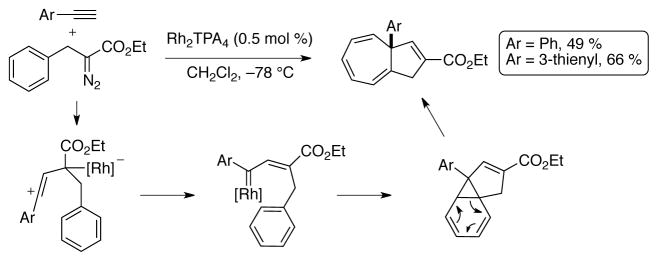

Interestingly, with Rh2TPA4 as the catalyst in the reactions of aryl alkynes and α-diazohydrocinnamate, yet another chemoselective pathway was accessed, and angularly substituted dihydroazulenes were obtained (Scheme 11). An alkyne insertion/Buchner ring expansion mechanism was proposed to rationalize the formation of these scaffolds.

Scheme 11.

Catalyst dependent chemoselectivity switch.

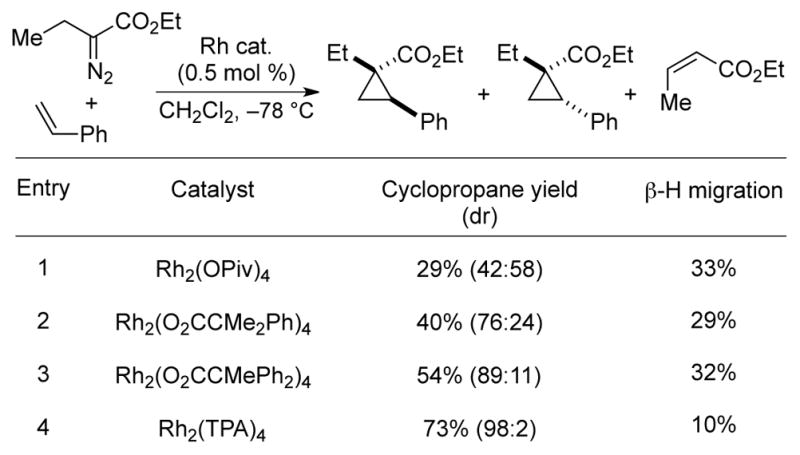

Cyclopropanation reactions of olefins could be similarly promoted with high selectivity over β-hydride migration at –78 °C with the appropriate choice of ligand.17 The use of Rh2(OPiv)4, the optimal catalyst for cyclopropenation, led to modest yield of cyclopropane isomers with poor diastereocontrol (Scheme 12). However, both yield and diastereoselectivity could be substantially improved by using bulkier ligands, with Rh2TPA4 proving to be optimal as the cyclopropane was formed in 73% yield and 98:2 dr. With Rh2TPA4, the diastereoselectivities with α-alkyl-α-diazoacetates are comparable to the high diastereoselectivity that can be obtained with α-aryl or α-vinyl diazoacetates.1d As discussed below, attractive substrate–ligand interactions can be critical to achieving stereoselectivity and favoring intermolecular reaction pathways over β-hydride migration. The greatly improved but still imperfect selectivity for cyclopropanation over alkene formation highlights the need for continued ligand development to completely suppress the β-hydride migration pathway.

Scheme 12.

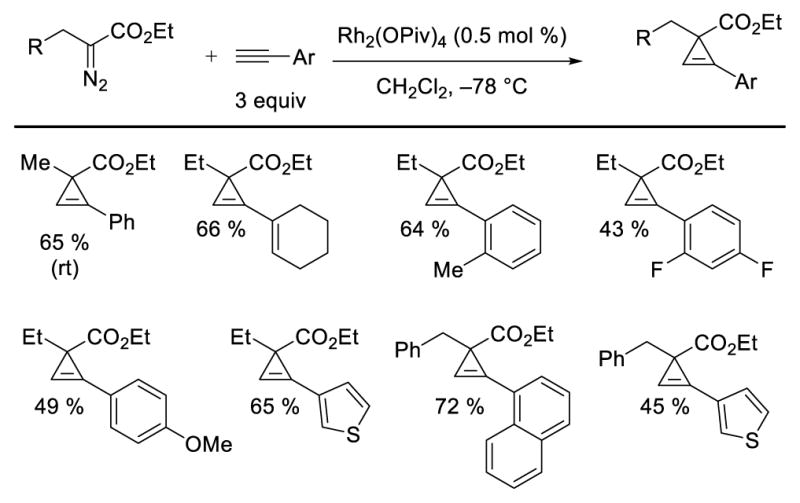

Effect of ligand choice on Rh-catalyzed cyclopropanation.

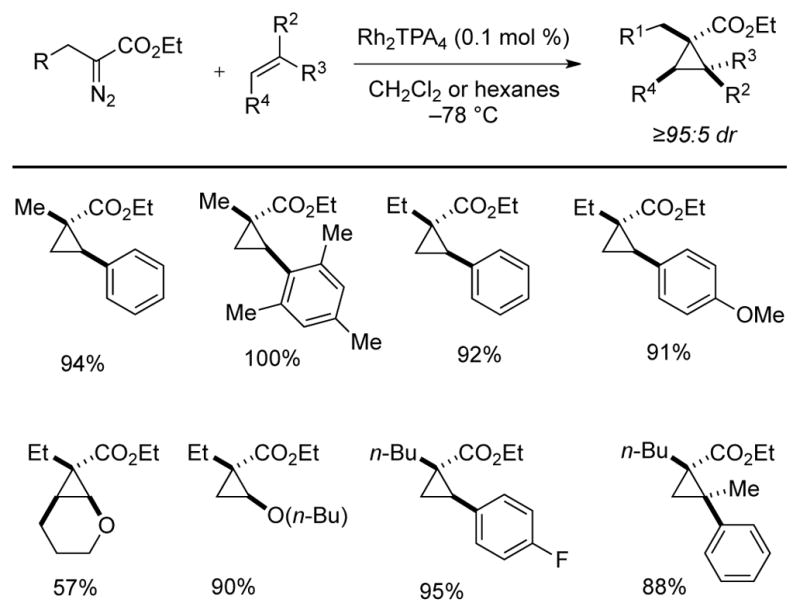

The Rh2TPA4-catalyzed cyclopropanation of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters was successful with a variety of olefins including styrene derivatives, dihydropyran, and butyl vinyl ether (Scheme 13).17 Excellent yields were obtained using the diazoester in excess. Good yields were also observed when the stoichiometry was inverted and olefin was used in 3-fold excess. In nearly all cases, the diastereoselectivity was ≥ 95:5.

Scheme 13.

Rh2TPA4-catalyzed cyclopropanation of olefins, selected examples.

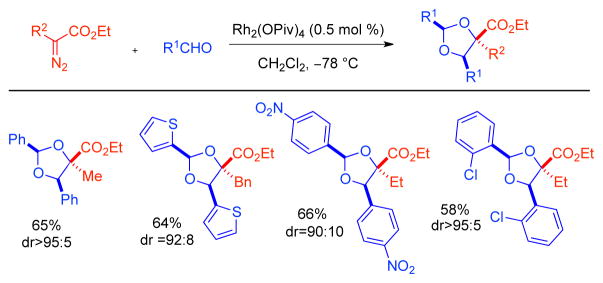

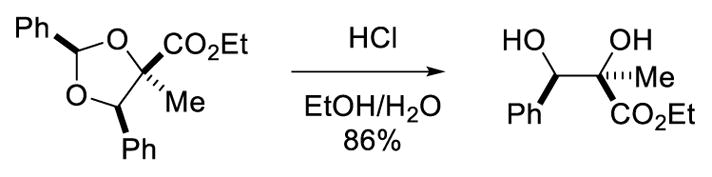

1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition reactions of carbonyl ylides can be used to rapidly and efficiently generate structurally complex heterocycles, and the Rh-catalyzed reaction between diazoesters and aldehydes is a well-established method to generate these dipoles. Although several examples of intramolecular reactions between carbonyls and Rh-carbenes have been reported with selectivity over β-hydride migration by Padwa and others,7 intermolecular variants were unknown. In addition to the issue of intramolecular β-hydride migration, carbonyl ylides can undergo electrocyclic ring closure to form epoxides,18 further react with carbonyls to form 1,3-dioxolanes,19 or react with external dipolarophiles to form dihydro- and tetrahydrofurans.19f,20 These pathways can be additionally complicated by the challenges of diastereo- and regioselectivity. As a result, multi-component Rh-catalyzed dipolar cycloaddition reactions that exhibit high chemo-, regio-, and stereocontrol were only known with extremely limited substrate scope.19c,d,f In reactions of aryl aldehydes and α-alkyl-α-diazoesters, Rh2(OPiv)4 was again found to be optimal in avoiding β-hydride migration, and 1,3-dioxolanes were formed in good to high yield with unusually high diastereoselectivity (Scheme 14). The requisite 2-aryl-1,3-dioxolanes are readily hydrolyzed, providing stereoselective access to substituted vicinal diols (Scheme 15).

Scheme 14.

Rh-catalyzed diastereoselective dioxolane formation, selected examples.

Scheme 15.

1,2-Diol synthesis via acetal hydrolysis.

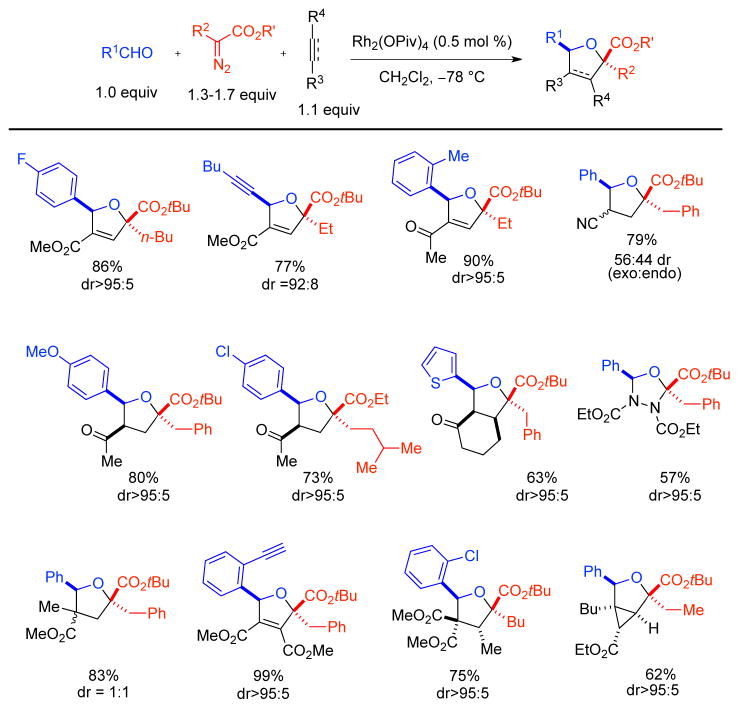

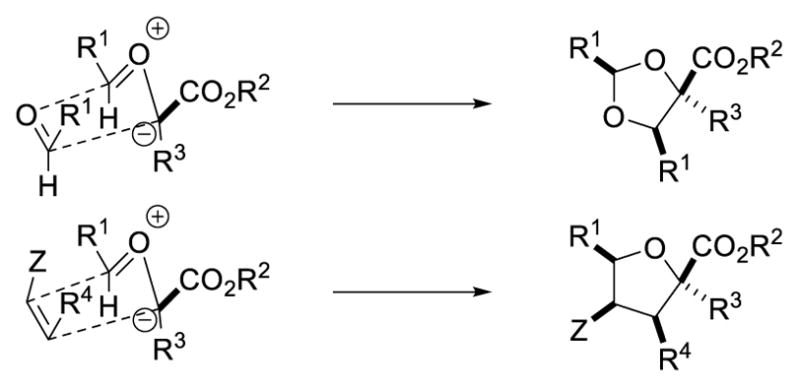

Given the unusually reactive nature of the putative carbonyl ylides derived from α-alkyl-α-diazoesters, we considered that it should be possible to intercept them with external dipolarophiles in three-component reactions. Indeed, we found that these ylides could be trapped by a wide variety of dipolarophiles in highly regio- and diastereoselective reactions to form densely functionalized dihydro- and tetrahydrofuran products (Scheme 16).21a In these cycloaddition reactions to form 1,3-dioxolanes or dihydro/tetrahydrofurans, the major diastereomer observed arises via an endo-transition state (Scheme 17).

Scheme 16.

Rh-catalyzed three-component cycloaddition reactions, selected examples.

Scheme 17.

Model for endo-selective 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions.

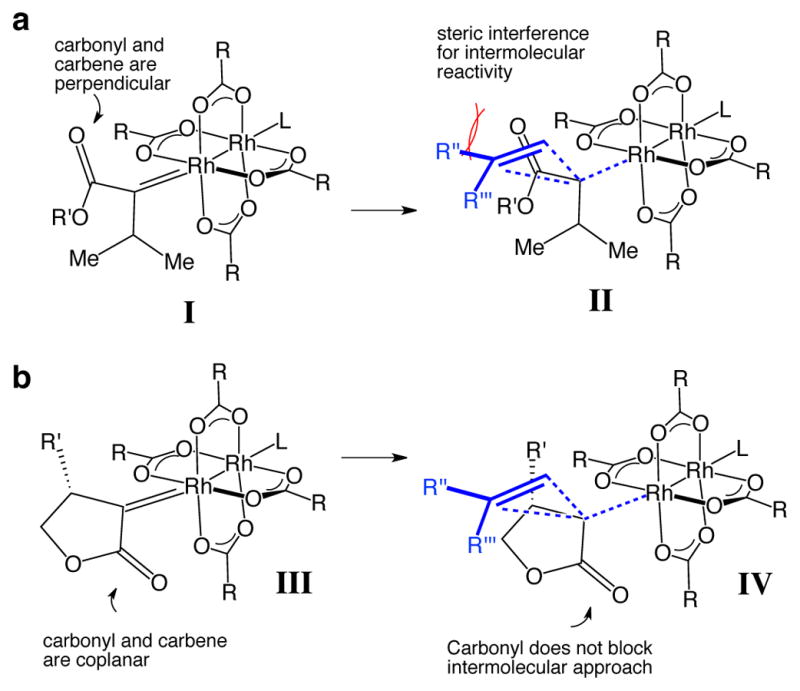

Chemoselective Rh-catalyzed reactions of α-diazocarbonyl compounds with tertiaryβC–H bonds are especially challenging, as intermolecular reactions of β-substituted α-diazocarbonyl compounds had only been described in cases where β-hydride migration would lead to highly-strained products. 22 In Rh-carbenes derived from α-alkyl-α-diazoesters, the carbonyl function is aligned perpendicular to the plane of the carbene to avoid conjugation with the electron-deficient carbene (Figure 1a). In this conformation, the carbonyl sterically hinders the intermolecular approach of substrates. We rationalized that with the use of β-substituted cyclic α-diazocarbonyl compounds, the ring would constrain the carbonyl and carbene to be more coplanar which would allow for a less hindered approach of substrates and accelerate intermolecular reactions (Figure 1b).3 Furthermore, β-substituted lactones, lactams, and cyclic ketones are readily accessed in enantioenriched form by asymmetric conjugate addition or conjugate reduction.23

Figure 1.

(a) Steric interaction between the carbonyl and approaching olefin in the cyclopropanation reaction of acyclic α-diazoesters. (b) The approach of the olefin to a carbene derived from a cyclic α-diazoester is relatively unhindered due to the coplanarity of the carbene and carbonyl.

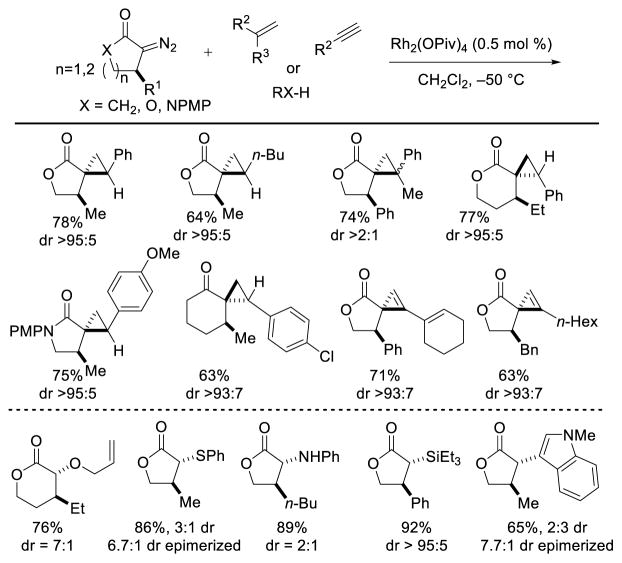

As with several of the previous systems we studied, Rh2(OPiv)4 was the optimal catalyst in a model cyclopropanation reaction of styrene with 3-diazo-4-methyldihydrofuran-2-one, giving cyclopropane in 85% yield and 95:5 dr (Scheme 18, top). The chemoselective intermolecular reactivity of cyclic α-diazocarbonyl compounds is broad. Cyclic α-diazo-β-substituted butyro- and valerolactone, butyrolactam, and cyclohexanone substrates were efficient carbene precursors, although an attempted cyclopropanation reaction using α-diazo-β-ethylcaprolactone failed. Successful reactivity was observed with varied olefin (cyclopropanation) and alkyne (cyclopropenation) substrates with high diastereoselectivity (≥93:7). The cyclic diazo compounds effectively engage α-olefins and aliphatic alkynes, both of which are challenging substrates with acyclic α-diazoesters.3 Furthermore, several X–H insertion reactions of alcohol, thiol, amine, silane, and indole substrates proceeded in good yield (Scheme 18, bottom).

Scheme 18.

Intermolecular reactions of cyclic α-diazocarbonyl compounds, selected examples.

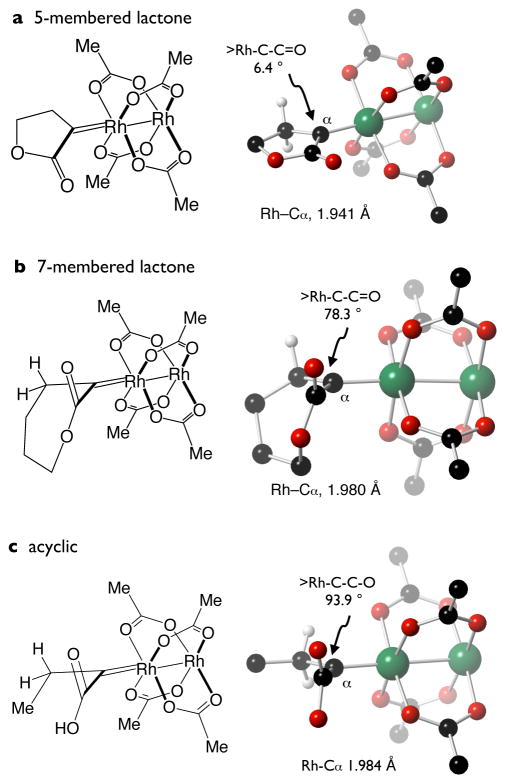

The ground states of Rh-carbenes derived from cyclic lactones of ring sizes 5-7 were examined computationally and compared to that of the carbene derived from (acyclic) α-diazobutyric acid (Figure 2). In line with previous studies,2c,24 the model Rh-carbene derived from α-diazobutyric acid features a nearly perpendicular arrangement of the carbonyl with respect to the Rh=C bond (Rh–C–C–O dihedral angle ∠93.9°). In contrast, the dihedral angles for the butyrolactone and valerolactone derived carbene are much smaller due to ring constraints (∠6.4° and ∠56.8° respectively). The conformational flexibility of the caprolactone-derived carbene is evidenced by its larger dihedral angle (∠78.3°), which approaches that of the acyclic Rh-carbene (∠93.9°).

Figure 2.

Computed structures of Rh-carbenes derived from Rh2(OAc)4 and (a) α-diazobutyrolactone, (b) α-diazocaprolactone and (c) α-diazobutyric acid.

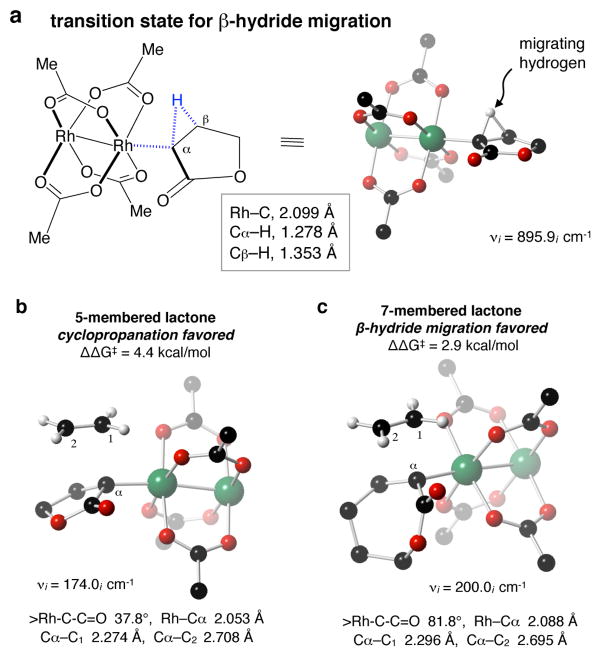

Transition state calculations were carried out for intermolecular cyclopropanation of these Rh-carbenes with ethylene and compared to that for β-hydride migration (Figure 3). We found the free energy of activation for cyclopropanation of the carbene derived from α-diazobutyrolactone to be lower than that for β-hydride migration by 4.4 kcal/mol. We observed similar results in the α-diazovalerolactone system. However, the calculated free energy of activation for cyclopropanation with the α-diazocaprolactone-derived carbene was higher in energy than the β-hydride migration pathway by 2.9 kcal/mol (similar to what was observed for the acyclic carbene system). These computational results supported our model in Figure 1, in which steric interactions between the carbonyl and the approaching alkene are ameliorated due to the ring constraints of butyro- and valerolactones, but remain significant for larger rings as well as acyclic substrates.

Figure 3.

Transition state structures for (a) β-hydride migration for the Rh-carbene derived from Rh2(OAc)4 and α-diazobutyrolactone, and (b,c) cyclopropanation by ethylene with carbenes derived from Rh2(OAc)4 and (b) α-diazobutyrolactone and (c) α-diazocaprolactone.

Temperature and Ligand Effects

Throughout our work, we have observed that Rh-carbenes are more resilient against β-hydride migration at low temperatures (typically –78 °C). The calculations described above provided insight into the origin of the temperature effect. In calculations on β-hydride migration and cyclopropanation, ΔH‡ is larger for the former, but ΔS‡ is larger for the latter. Thus, lower temperature favors intermolecular processes by decreasing the contribution of the entropic term. Selectivity is also highly dependent on the nature of the carboxylate ligands, with the counterintuitive finding that bulky ligands favor intermolecular reactivity, which requires a more sterically demanding transition state than β-hydride migration. Our computational models suggest that attractive substrate-ligand interactions may be responsible for the observation that bulky ligands favor intermolecular reactivity. These effects will be discussed in detail in the next section in the context of enantioselective reactivity.

Catalytic Enantioselective Intermolecular Reactions

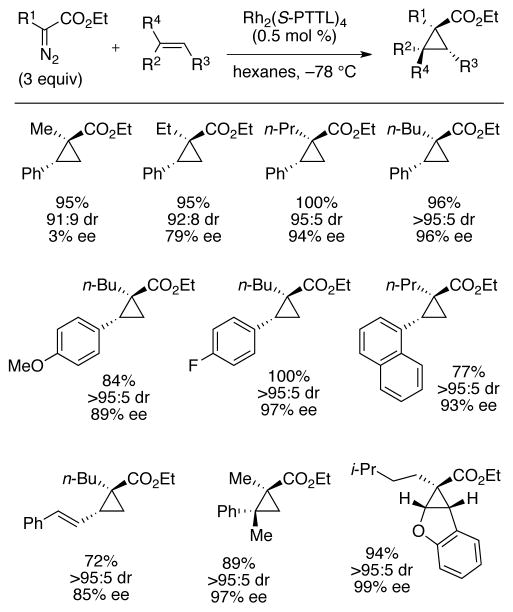

Following our success in developing conditions for diastereoselective intermolecular cyclopropanation with selectivity over β-hydride migration, we turned our attention to the development of an asymmetric variant. Dirhodium tetracarboxylate complexes with N-imido-tert-leucinate ligands, pioneered by Hashimoto,25,27,32 have been especially effective. We found that the tert-leucine-derived catalyst Rh2(S-PTTL)425 was highly efficient at catalyzing enantioselective cyclopropanation reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters with olefins at –78 °C. Cyclopropanes were formed in generally high yields with excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity as well as high chemoselectivity over β-hydride migration. Interestingly, we noticed a sharp rise in enantioselectivity as the size of the alkyl group on the diazo compound was increased (Scheme 19).21b

Scheme 19.

Enantioselective cyclopropanation, selected examples.

Although α-diazopropionates afforded cyclopropanes in poor enantioselectivity with Rh2(S-PTTL)4 (3% ee), Hashimoto subsequently described a system for cyclopropanation of α-diazopropionates using the brominated Rh2(S-TBPTTL)4 with up to 92% ee.26

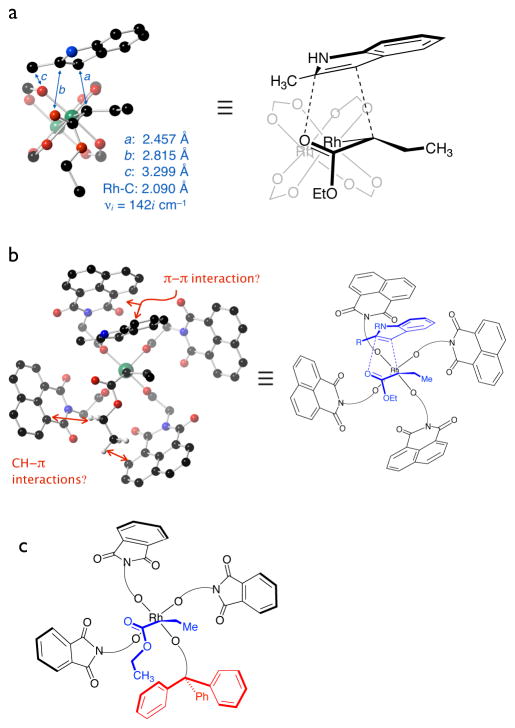

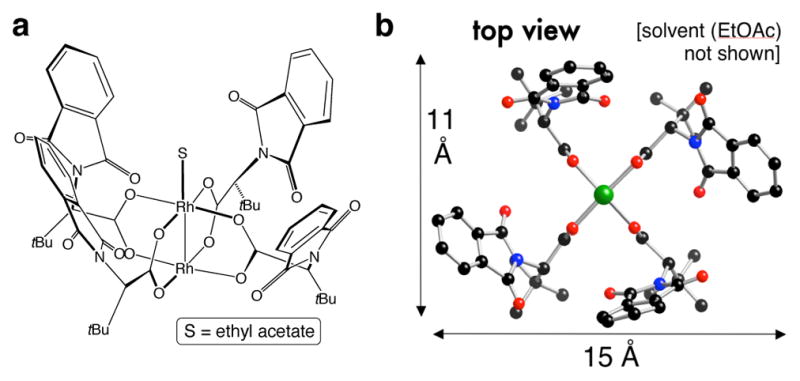

To gain a better understanding of the mechanism of asymmetric induction, we performed X-ray crystallographic and computational studies on Rh2(S-PTTL)4, and discovered a conformation not previously observed for chiral dirhodium paddlewheel complexes.27 We refer to this as the “chiral crown” conformation of Rh2(S-PTTL)4, where all four of the phthalimido groups are projected onto the same face of the macromolecular structure (Figure 4). The four tert-butyl groups are projected onto the opposite face of the catalyst. Concurrent studies by Charette also established the chiral crown conformation in halogenated analogues, and halogen bonding has been proposed to add stability to the crown conformer.28 Later studies by us,29 Charette,30 Ghanem,31 Hashimoto32 and Reger33 have provided additional crystallographic support for the chiral crown structure.

Figure 4.

(a) In the chiral crown conformation, all four phthalimido groups are projected onto one face and all four tert-butyl groups are projected onto the opposite face. (b) X-ray structure of Rh2(S-PTTL)4.

Based on X-ray crystallographic and computational studies on Rh2(S-PTTL)4, we proposed a model for asymmetric induction where reactivity takes place preferentially on the face of the catalyst substituted by the phthalimides. Our further studies29 revealed that the bulky tert-butyl groups play a significant role in enforcing the chiral crown structure, and it was found that other tert-leucine-derived complexes crystallize in similar conformations including copper-derived Cu2(S-PTTL)4 and the naphthaloyl analog Rh2(S-NTTL)4.34

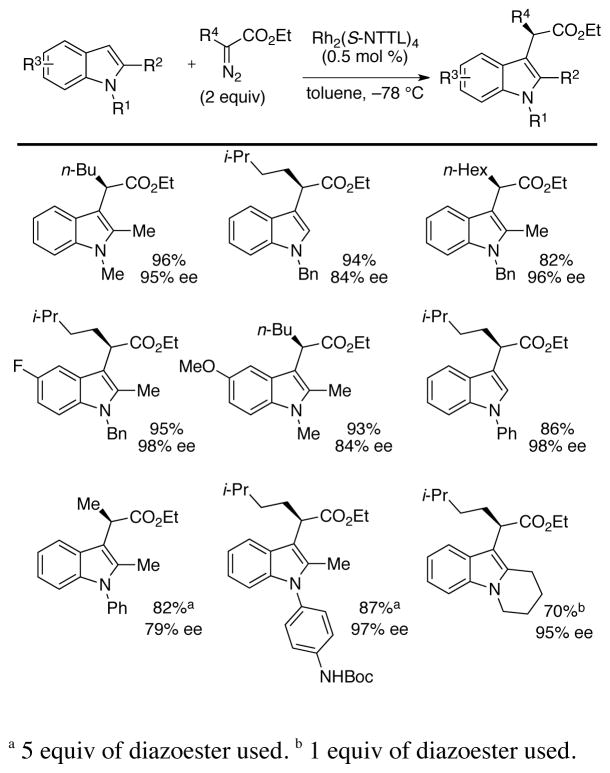

We hypothesized that asymmetric reactions between α-alkyl-α-diazoesters and indoles could be promoted by chiral crown Rh-complexes. The indole core is a ubiquitous structural element in various biologically active molecules and pharmaceutical targets. Although the selective C–H functionalization of indoles by carbene intermediates had been long known,35 there had been no report of an asymmetric variant. The only known catalytic enantioselective reaction between indoles and α –diazocarbonyl compounds was a [3+2] annulation strategy that had been recently developed by Davies.36 We explored reactivity with a number of chiral crown Rh-complexes, and found that high yields (82 – 96%) and enantioselectivities (79 – 97% ee) were obtained using catalytic Rh2(S-NTTL)4 at –78 °C (Scheme 20).21c

Scheme 20.

Enantioselective C–H functionalization of indoles, selected examples.

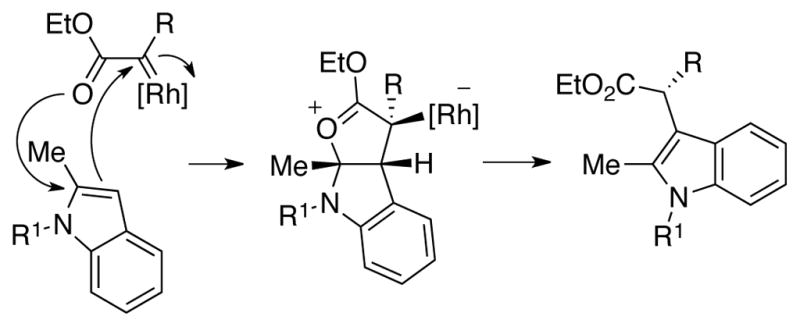

For indole C–H functionalization, experimental and computational studies supported the mechanism shown in Scheme 21 in which an initially formed oxocarbenium-stabilized intermediate is formed through the transition state depicted in Figure 5a. More recently, Xie has computationally studied the stereospecific conversion of the oxocarbenium Rh-ylide to the indole product, and proposed a cyclic ketene acetal intermediate.37 For both cyclopropanation and indole functionalization, we proposed models for asymmetric induction in which the substrate approaches via the Si-face of the carbene. As shown in Figure 5b, the model for indole functionalization suggested that enantioselectivity was influenced by attractive π–π interactions between indole and the top naphthaloyl ligand, as well as C–H-π interactions between the ethyl ester and the bottom naphthaloyl ligands.

Scheme 21.

Formation of C-3-functionlized indole via an oxocarbenium-stabilized ylide intermediate.

Figure 5.

(a) Calculated transition state for the reaction between 2-methylindole and Et(EtO2C)C=Rh2(O2CH)4. (b) Model for indole C–H functionalization suggests that attractive substrate-ligand interaction may contribute to enantioselectivity. (c) Design of a mixed-ligand complex, where the chiral pocket is maintained and tuned by replacing one of the chiral ligands with achiral triphenylacetate.

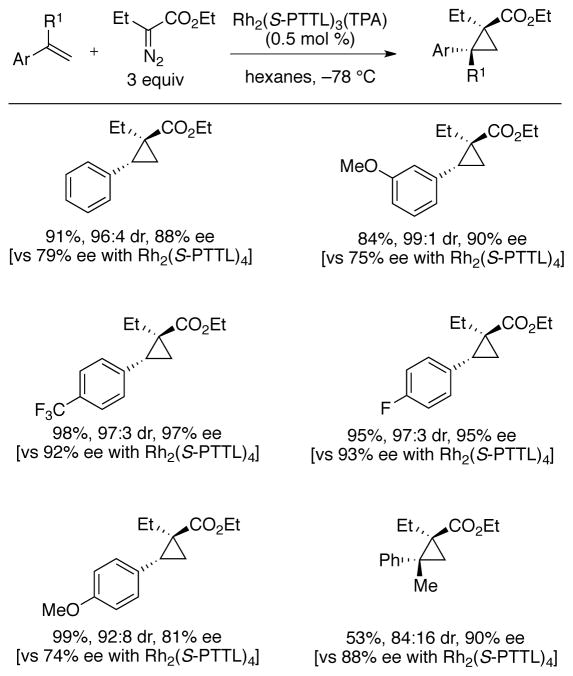

These observations led us to hypothesize that there might be a beneficial effect on catalyst selectivity if one of the chiral ligands of Rh2(S-PTTL)4 was replaced by an achiral carboxylate ligand as in Figure 5c. Based on modeling, we hypothesized that the chiral pocket would be maintained, and given the importance of non-covalent interactions we reasoned that introducing a ligand with a large aromatic surface area could be beneficial. Accordingly, we synthesized the mixed-ligand complex Rh2(S-PTTL)3(TPA), and through X-ray crystallographic and computational studies, the chiral crown configuration was indeed found to be conserved (Figure6).

Figure 6.

(a) Synthesis of mixed ligand complex Rh2(S-PTTL)3(TPA), which adopts a crownlike structure. There is overall good agreement between (b) the X-ray and (c) predicted structure.

This catalyst proved to be broadly useful for enantioselective cyclopropanation reactions with ethyl 2-diazobutanoate; reactions that were challenging to achieve high enantiomeric excess using Rh2(S-PTTL)4. For example, the reaction between ethyl 2-diazobutanoate and styrene gave only 79% ee with Rh2(S-PTTL)4, but was improved to 88% ee with Rh2(S-PTTL)3(TPA) (Scheme 22). Similar improvements in enantioselectivity over Rh2(S-PTTL)4 were observed across several olefin substrates.21d

Scheme 22.

Rh2(S-PTTL)3(TPA)-catalyzed cyclopropanation of olefins withα-alkyl-α-diazoesters, selected examples.

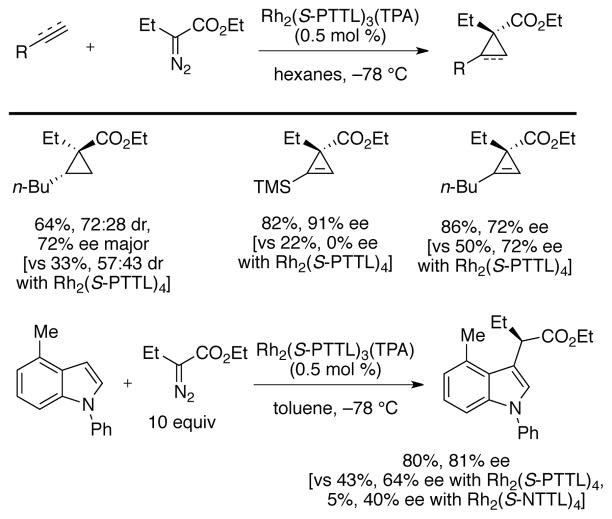

In addition to improving enantioselectivity, Rh2(S-PTTL)3(TPA) also provided chemoselective advantages over homoleptic complexes in terms of avoiding β-hydride migration with challenging substrates (Scheme 23). For instance, simple α-olefins had been poor substrates for cyclopropanation with α-alkyl-α-diazoesters. With Rh2(S-PTTL)3(TPA), 1-hexene and iso-butyl 2-diazobutanoate gave 64% of the cyclopropane product with useful selectivity over β-hydride migration. Furthermore, other challenging substrates including silyl- and aliphatic alkynes as well as 4-substituted indoles reacted with ethyl 2-diazobutanoate using Rh2(S-PTTL)3(TPA).

Scheme 23.

Reactions of ethyl 2-diazobutanoate with challenging coupling partners.

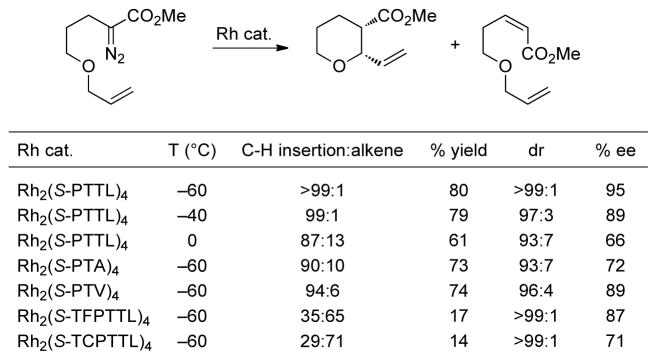

Recently, Hashimoto has investigated the effects of ligand size and temperature on the chemoselectivity of intramolecular C–H insertions in the formation of tetrahydropyrans over β-hydride migration products (Scheme 24).38a With Rh2(S-PTTL)4, at temperatures below –40 °C, β-hydride migration was suppressed and tetrahydropyrans were formed in high yields. Ligand and temperature effects are displayed in Scheme 24.

Scheme 24.

Temperature and ligand dependent chemoselectivity of Rh-catalyzed intramolecular

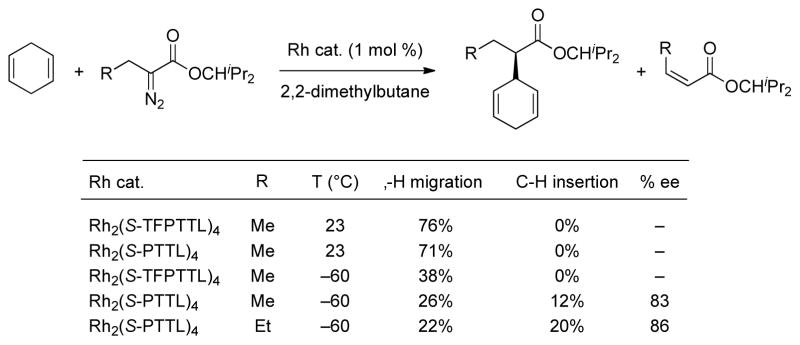

In 2012, Hashimoto reported the first enantioselective intermolecular C–H insertions of α-alkyl-α-diazoacetates.38b He demonstrated α-diazopropionates combine with 1,4-cyclohexadiene with good selectivity over β-hydride migration. However, in the case α-diazobutanoates and α-diazopentanoates, β-hydride migration dominated (Scheme 25). Using Rh2(S-PTTL)4 at –60 °C, C–H insertion products were formed in 12% and 20%, respectively. At room temperature or with electron poor Rh-catalysts, C–H insertion was not observed.

Scheme 25.

Examples of C–H insertion reactions in the presence of β-hydrogens.

Asymmetric Cyclobutane Synthesis via Intramolecular Bicyclobutanation/Homoconjugate Addition

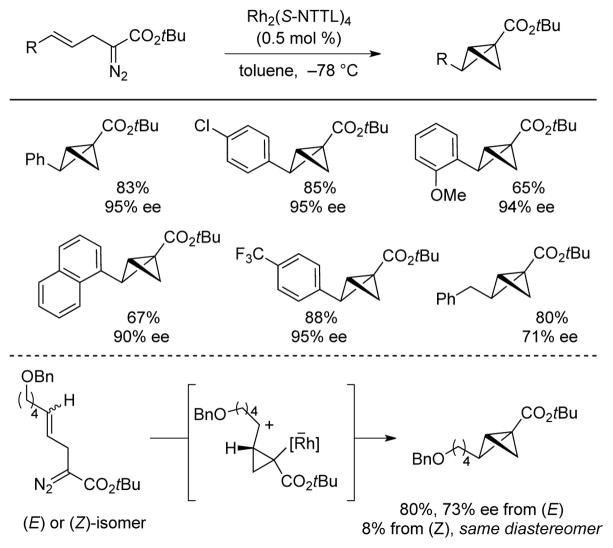

Bicyclobutanes are extremely useful synthetic building blocks, as ring opening reactions can provide access to highly functionalized molecules.39 We envisioned that general conditions could be developed for the homoconjugate addition of Grignard reagents, with subsequent enolate trapping to form highly functionalized cyclobutanes. In 1981, Ganem first prepared bicyclobutane carboxylates via treatment of ethyl α-allyl-α-diazoacetate with Rh2(OAc)4 to give ethyl bicyclobutane-1-carboxylate (51%) along with competing β-hydride migration (39%).4a Concurrent with our studies, Davies reported an enantioselective Rh2(R-BTPCP)4-catalyzed bicyclobutane synthesis using methyl and ethyl (E)-2-diazo-5-arylpent-4-enoates.40 We developed a complementary approach that gives access to tert-butyl bicyclobutane-1-carboxylates —substrates compatible with subsequent homoconjugate addition reactions.41 Rh2(S-NTTL)4 was highly effective in bicyclobutanation reactions of tert-butyl (E)-2-diazo-5-arylpent-4-enoates, giving bicyclobutane products in 65 – 88% yield and with 71 – 95% ee (Scheme 26). Interestingly, the (E)- and (Z)-olefin isomers of the diazoester both provided the identical diastereomer of the bicyclobutane, supporting a stepwise mechanism involving a zwitterionic intermediate.

Scheme 26.

Enantioselective bicyclobutanation, selected examples.

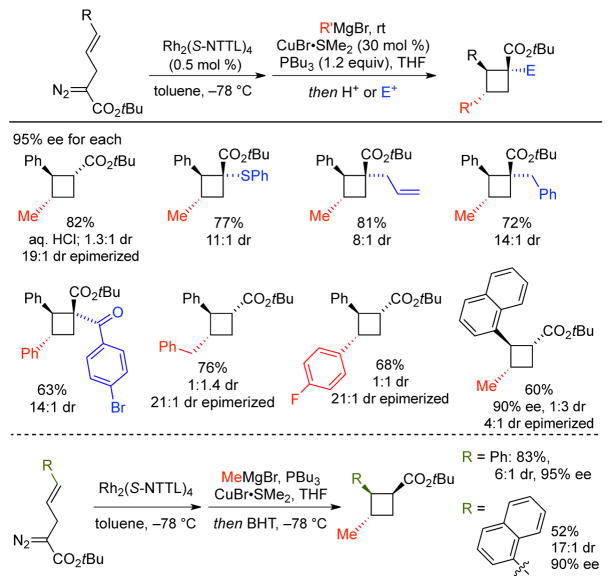

A CuBr•SMe2/PBu3 catalyst system was developed for the homoconjugate addition of Grignard reagents to bicyclobutanes, and cyclobutane products were isolated in 60 – 82% yield upon electrophile capture (Scheme 27). Successful electrophiles included allyl iodide, EtI, BnBr, PhSSPh, and 4-bromobenzoyl chloride to generate quaternary carbon-containing cyclobutanes with good diastereocontrol (7:1 – 14:1 dr). When 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT) was used as a sterically demanding proton source, diastereoselective kinetic protonation was observed (1:6 – 1:17 dr). In contrast, aqueous acid-quenched products were obtained as roughly 1:1 mixtures of epimers at the α-stereocenter. However, the diastereomeric ratio was vastly improved upon epimerization with t-BuOK (up to 30:1 dr), providing the complementary diastereomer relative to that from kinetic protonation by BHT.41

Scheme 27.

One-flask, multi-component cyclobutane synthesis, selected examples.

Summary

This account describes the development of catalyst systems that enable the Rh-catalyzed reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds with selectivity over intramolecular β-hydride migration. The use of sterically demanding ligands and low reaction temperatures has enabled intermolecular cyclopropenation, cyclopropanation, carbonyl ylide formation/dipolar cycloaddition, indole C–H functionalization, and intramolecular bicyclobutanation. Enantioselective variants have been developed using bimetallic N-imido-tert-leucinate-substituted complexes that were shown to adopt an unprecedented “chiral crown” conformation. Through computational design and transition state modeling, we have developed chiral, mixed ligand complexes that further broaden the substrate scope of enantioselective reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

For financial support we thank NSF CHE 1300329. Spectra were obtained with instrumentation supported by NIH P20GM104316, P30GM110758, S10RR026962-01, S10OD016267-01 and NSF grants: CHE 0840401 and CHE-1229234.

We are deeply grateful to our co-workers Olga Dmitrenko, Patricia Panne, Srinivasa Chintala, Michael Taylor, David Boruta, Valerie Shurtleff, and Yinzhi Fang.

Biographies

Joseph Fox was born in Philadelphia. He received the A.B. in 1993 from Princeton University where he conducted research with Maitland Jones, Jr. In 1998, he received the Ph.D. from Columbia University under the direction of Thomas Katz. After an NIH postdoctoral fellowship with Stephen Buchwald at MIT, he joined the faculty of the University of Delaware in 2001, where is currently Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, and Director of an NIH Center of Biomedical Research Excellence.

Andrew DeAngelis received his B.S. in Chemistry from Moravian College in 2005 where he conducted undergraduate research with Carl Salter. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Delaware in 2011 under the guidance of Joseph Fox. Following postdoctoral studies with Stephen Buchwald at MIT, he joined Johnson Matthey Catalysis and Chiral Technologies in West Deptford, NJ in 2012. In 2015 he joined the chemical discovery group at DuPont Crop Protection in Newark, DE as a research investigator.

Robert Panish was born in Norristown, PA. He received his B.S. in chemistry from Elizabethtown College in 2010 where he conducted undergraduate research with James MacKay. In 2010, he began at the University of Delaware where he is pursuing his Ph.D. under the guidance of Joseph Fox. In 2016, he plans to join the process research division of Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Notes

Any additional relevant notes should be placed here.

References

- 1.(a) Ford A, Miel H, Ring A, Slattery CN, Maguire AR, McKervey MA. Modern Organic Synthesis with α-Diazocarbonyl Compounds. Chem Rev. 2015;115:9981–10080. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML, Morton D. Guiding Principles for Site Selective and Stereoselective Intermolecular C–H Functionalization by Donor/Acceptor Rhodium Carbenes. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1857–1869. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00217h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Doyle MP. Perspective on Dirhodium Carboxamidates as Catalysts. J Org Chem. 2006;71:9253–9260. doi: 10.1021/jo061411m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chepiga KM, Qin C, Alford JS, Chennamadhavuni S, Gregg TM, Olson JP, Davies HML. Guide to Enantioselective Dirhodium(II)-Catalyzed Cyclopropanation with Aryldiazoacetates. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:5765–5771. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2013.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kornecki KP, Briones JF, Boyarskikh V, Fullilove F, Autschbach J, Schrote KE, Lancaster KM, Davies HML, Berry JF. Direct Spectroscopic Characterization of a Transitory Dirhodium Donor-Acceptor Carbene Complex. Science. 2013;342:351–354. doi: 10.1126/science.1243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Snyder JP, Padwa A, Stengel T, Arduengo AJ, III, Jockisch A, Kim H-J. A Stable Dirhodium Tetracarboxylate Carbenoid: Crystal Structure, Bonding Analysis, and Catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11318–11319. doi: 10.1021/ja016928o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakamura E, Yoshikai N, Yamanaka M. Mechanism of C-H Bond Activation/C-C Bond Formation Reaction between Diazo Compound and Alkane Catalyzed by Dirhodium Tetracarboxylate. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7181–7192. doi: 10.1021/ja017823o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pirrung MC, Liu H, Morehead AT., Jr Rhodium Chemzymes: Michaelis-Menten Kinetics in Dirhodium(II) Carboxylate-Catalyzed Carbenoid Reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1014–1023. doi: 10.1021/ja011599l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Werlé C, Goddard R, Fürstner A. The First Crystal Structure of a Reactive Dirhodium Carbene Complex and a Versatile Method for the Preparation of Gold Carbenes by Rhodium-to-Gold Transmetalation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015 doi: 10.1002/anie.201506902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeAngelis A, Dmitrenko O, Fox JM. Rh-Catalyzed Intermolecular Reactions of Cyclic α-Diazocarbonyl Compounds with Selectivity over Tertiary C–H Bond Migration. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11035–11043. doi: 10.1021/ja3046712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Ikota N, Takamura N, Young SD, Ganem B. Catalyzed Insertion Reactions of Substituted α-Diazoesters. A New Synthesis of cis-Enoates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:4163–4166. [Google Scholar]; (b) McKervey MA, Ratananukul P. Regiospecific Synthesis of α-(Phenylthio)ketones via Rhodium(II) Acetate Catalysed Addition of Thiophenol to α–Diazoketones. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:2509–2512. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Early examples of intramolecular Rh-catalyzed cyclopropanation: ref 3 and Baird MS, Hussain HH. The Preparation and Decomposition of Alkyl 2-Diazopent-4-Enoates and 1-Trimethylsilyl-1-Diazobut-3-Enes. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:215–224.Taber DF, Hoerrner RS. Enantioselective Rhodium-Mediated Synthesis of (–)-PGE2 Methyl Ester. J Org Chem. 1992;57:441–447.

- 6.Early examples of intramolecular Rh-catalyzed alkyne insertion: Padwa A, Hertzog DL, Chinn RL. Synthesis of AZA Substituted Polycycles via Rhodium (II) Carboxylate Induced Cyclization of Diazoimides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:4077–4080.Padwa A, Dean DC, Hertzog DL, Nadler WR, Zhi L. Azomethine Ylide Generation via the Dipole Cascade. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:7565–7580.

- 7.Intramolecular Rh-catalyzed reactions that form putative carbonyl ylides: Padwa A, Kulkarni YS, Zhang Z. Reaction of Carbonyl Compounds with Ethyl Lithiodiazoacetate. Studies Dealing with the Rhodium(II)-Catalyzed Behavior of the Resulting Adducts. J Org Chem. 1990;55:4144–4153.Padwa A, Hornbuckle SF, Fryxell GE, Zhang ZJ. Tandem Cyclization-Cycloaddition Reaction of Rhodium Carbenoids. Studies Dealing with Intramolecular Cycloadditions. J Org Chem. 1992;57:5747–5757.. Also see ref 6

- 8.Intramolecular insertion into C–S bonds: Kametani T, Kawamura K, Tsubuki M, Honda T. Synthesis of Aromatic Sesquiterpenes, (±)-Cuparene and (±)-Laurene by Means of an Intramolecular Carbenoid Displacement (ICD) Reaction. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1988;1:193–199.. Intramolecular insertion into C–S bonds and C–Se bonds: Kametani T, Yukawa H, Honda T. A Novel Synthesis of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids by Means of an Intramolecular Carbenoid Displacement (ICD) Reaction. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1988;1:833–837.

- 9.Lead examples of Intramolecular Rh-catalyzed C–H insertion: Taber DF, Hennessy MJ, Louey JP. Rh-Mediated Cyclopentane Construction Can Compete with β-Hydride Elimination: Synthesis of (±)-Tochuinyl Acetate. J Org Chem. 1992;57:436–441.Taber DF, You KK. Highly Diastereoselective Cyclopentane Construction: Enantioselective Synthesis of the Dendrobatid Alkaloid 251F. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5757–5762.Taber DF, Joshi PV. Cyclopentane Construction by Rh-Catalyzed Intramolecular C–H Insertion: Relative Reactivity of a Range of Catalysts. J Org Chem. 2004;69:4276–4278. doi: 10.1021/jo0303766.Taber DF, Sheth RB, Joshi PV. Simple Preparation of α-Diazo Esters. J Org Chem. 2005;70:2851–2854. doi: 10.1021/jo048011o.Minami K, Saito H, Tsutsui H, Nambu H, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Highly Enantio- and Diastereoselective Construction of 1,2-Disubstituted Cyclopentane Compounds by Dirhodium(II) Tetrakis[N-phthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate]-Catalyzed C–H Insertion Reactions of α-Diazo Esters. Adv Synth Catal. 2005;347:1483–1487.Takeda K, Oohara T, Anada M, Nambu H, Hashimoto S. A Polymer-Supported Chiral Dirhodium(II) Complex: Highly Durable and Recyclable Catalyst for Asymmetric Intramolecular C–H Insertion Reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:6979–6983. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003730.

- 10.Intramolecular Rh-catalyzed O–H insertion: Sarabia-García F, López-Herrera FJ, Pino-González MS. A New Synthesis for 2-Deoxy-KDO, a Potent Inhibitor of CMP=KDO Synthetase. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:6709–6712.

- 11.Intramolecular Rh-catalyzed N–H insertion: Davis FA, Yang B, Deng J. Asymmetric Synthesis of cis-5-tert-Butylproline with Metal Carbenoid N–H Insertion. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5147–5152. doi: 10.1021/jo030081s.

- 12.Intermolecular, Rh-catalyzed Si–H insertion: Landais Y, Planchenault D. Asymmetric Metal Carbene Insertion into the Si–H Bond. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:4565– 4568.

- 13.Lead references to intermolecular, Rh-catalyzed N–H insertion, see ref 9d and: Cobb JE, Blanchard SG, Boswell EG, Brown KK, Charifson PS, Cooper JP, Collins JL, Dezube M, Henke BR, Hull-Ryde EA, Lake DH, Lenhard JM, Oliver W, Jr, Oplinger J, Pentti M, Parks DJ, Plunket KD, Tong W-Q. N-(2-Benzoylphenyl)- L-tyrosine PPARγ Agonists. 3. Structure-Activity Relationship and Optimization of the N-Aryl Substituent. J Med Chem. 1998;41:5055–5069. doi: 10.1021/jm980414r.Henke BR, Blanchard SG, Brackeen MF, Brown KK, Cobb JE, Collins JL, Harrington WW, Jr, Hashim MA, Hull-Ryde EA, Kaldor I, Kliewer SA, Lake DH, Leesnitzer LM, Lehmann JM, Lenhard JM, Orband-Miller LA, Miller JF, Mook RA, Jr, Noble SA, Oliver W, Jr, Parks DJ, Plunket KD, Szewczyk JR, Willson TM. N-(2-Benzoylphenyl)-L-tyrosine PPARγ Agonists. 1. Discovery of a Novel Series of Potent Antihyperglycemic and Antihyperlipidemic Agents. J Med Chem. 1998;41:5020–5036. doi: 10.1021/jm9804127.

- 14.Lead references to intermolecular, Rh-catalyzed O–H insertion, see see ref 9d and: Cox GG, Haigh D, Hindley RM, Miller DJ, Moody CJ. Competing O–H Insertion and β-Elimination in Rhodium Carbenoid Reactions, Synthesis of 2-Alkoxy-3-arylpropanoates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:3139–3142.Buckle DR, Cantello BCC, Cawthorne MA, Coyle PJ, Dean DK, Faller A, Haigh D, Hindley RM, Jefcott LJ, Lister CA, Pinto IL, Rami HK, Smith DG, Smith SA. Non Thiazolidinedione Antihyperglycaemic Agents. 1: α-Heteroatom Substituted β-Phenylpropanoic Acids. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1996;6:2121–2126.López-Herrera FJ, Sarabia-García F. Condensation of D-Mannosaldehyde Derivatives with Ethyl Diazoacetate. An Easy and Stereoselective Chain Elongation Methodology for Carbohydrates: Application to New Syntheses for KDO and 2-Deoxy-β-KDO. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:3325–3346.Wood JL, Moniz GA, Pflum DA, Stoltz BM, Holubec AA, Dietrich H-J. Development of a Rhodium Carbenoid-Initiated Claisen Rearrangement for the Enantioselective Synthesis of α-Hydroxy Carbonyl Compounds. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1748–1749.

- 15.For Ir-catalyzed Si–H insertion with α-diazocarbonyl compounds with primary α-alkyl substitutents, see: Yasutomi Y, Suematsu H, Katsuki T. Iridium(III)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Si–H Bond Insertion and Formation of an Enantioenriched Silicon Center. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4510–4511. doi: 10.1021/ja100833h.

- 16.Panne P, Fox JM. Rh-Catalyzed Intermolecular Reactions of Alkynes with α-Diazoesters That Possess β-Hydrogens: Ligand-Based Control over Divergent Pathways. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:22–23. doi: 10.1021/ja0660195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panne P, DeAngelis A, Fox JM. Rh-Catalyzed Intermolecular Cyclopropanation with α-Alkyl-α-Diazoesters: Catalyst-Dependent Chemo- and Diastereoselectivity. Org Lett. 2008;10:2987–2989. doi: 10.1021/ol800983y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Doyle MP, Hu W, Timmons DJ. Epoxides and Aziridines from Diazoacetates via Ylide Intermediates. Org Lett. 2001;3:933–935. doi: 10.1021/ol015600x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML, DeMesse J. Stereoselective Synthesis of Epoxides by Reaction of Donor/Acceptor-Substituted Carbenoids with α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:6803–6805. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Huisgen R, de March P. Three-Component Reactions of Diazomalonic Ester, Benzaldehyde, and Electrophilic Olefins. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4953–4954. [Google Scholar]; (b) Doyle MP, Forbes DC, Protopopova MN, Stanley SA, Vasbinder MM, Xavier KR. Stereocontrol in Intermolecular Dirhodium(II)-Catalyzed Carbonyl Ylide Formation and Reactions. Dioxolanes, and Dihydrofurans. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7210–7215. doi: 10.1021/jo970641l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jiang B, Zhang X, Luo Z. High Diastereoselectivity in Intermolecular Carbonyl Ylide Cycloaddition with Aryl Aldehyde Using Methyl Diazo(trifluoromethyl)acetate. Org Lett. 2002;4:2453–2455. doi: 10.1021/ol0200854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nair V, Mathai S, Mathew SC, Rath NP. A Stereoselective Synthesis of Spiro-Dioxolanes via the Multicomponent Reaction of Dicarbomethoxycarbene, Aldehydes, and 1,2- or 1,4-Diones. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:2849–2856. [Google Scholar]; (e) Lu C-D, Chen Z-Y, Liu H, Hu W-H, Mi A-Q. Highly Chemoselective 2,4,5-Triaryl-1,3-dioxolane Formation from Intermolecular 1,3-Dipolar Addition of Carbonyl Ylide with Aryl Aldehydes. Org Lett. 2004;6:3071–3074. doi: 10.1021/ol0489494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Skaggs AJ, Lin EY, Jamison TF. Cobalt Cluster-Containing Carbonyl Ylides for Catalytic, Three-Component Assembly of Oxygen Heterocycles. Org Lett. 2002;4:2277–2280. doi: 10.1021/ol026149s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Muthusamy S, Gunanathan C, Nethaji M. Multicomponent Reactions of Diazoamides: Diastereoselective Synthesis of Mono- and Bis-Spirofurooxindoles. J Org Chem. 2004;69:5631–5637. doi: 10.1021/jo0493119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nair V, Mathai S, Varma RL. The Three-Component Reaction of Dicarbomethoxycarbene, Aldehydes, and β-Nitrostyrenes: A Stereoselective Synthesis of Substituted Tetrahydrofurans. J Org Chem. 2004;69:1413–1414. doi: 10.1021/jo035673p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) DeAngelis A, Taylor MT, Fox JM. Unusually Reactive and Selective Carbonyl Ylides for Three-Component Cycloaddition Reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1101–1105. doi: 10.1021/ja807184r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) DeAngelis A, Dmitrenko O, Yap GPA, Fox JM. Chiral Crown Conformation of Rh2(S-PTTL)4: Enantioselective Cyclopropanation with α-Alkyl-α-diazoesters. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7230–7231. doi: 10.1021/ja9026852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) DeAngelis A, Shurtleff VW, Dmitrenko O, Fox JM. Rhodium(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective C–H Functionalization of Indoles. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1650–1653. doi: 10.1021/ja1093309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Boruta DT, Dmitrenko O, Yap GPA, Fox JM. Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA–a mixed-ligand dirhodium(II) catalyst for enantioselective reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters. Chem Sci. 2012;3:1589–1593. doi: 10.1039/C2SC01134D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Bagheri V, Doyle MP, Taunton J, Claxton EE. A New and General Synthesis of α-Silyl Carbonyl Compounds by Silicon-Hydrogen Insertion from Transition Metal-Catalyzed Reactions of Diazo Esters and Diazo Ketones. J Org Chem. 1988;53:6158– 6160. [Google Scholar]; (b) Giddings PJ, John DI, Thomas EJ. Preparation and Reduction of 6-Phenylselenylpenicillanates. A Stereoselective Synthesis of 6B-Substituted Penicillanates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:399–402. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hanlon B, John DI. Aspects of the Chemistry of 6-Diazopenicillanate S-Oxide and S,S-Dioxide. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1986;1:2207–2212. [Google Scholar]; (d) Matlin SA, Chan L. Metal-Catalysed Reactions of Benzhydryl 6-Diazopenicillanate with Alcohols. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1980:798–799. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Alexakis A, Bäckvall JE, Krause N, Pàmies O, Diéguez M. Enantioselective Copper-Catalyzed Conjugate Addition and Allylic Substitution Reactions. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2796–2823. doi: 10.1021/cr0683515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Feringa BL. Phosphoramidites: Marvellous Ligands in Catalytic Asymmetric Conjugate Addition. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:346–353. doi: 10.1021/ar990084k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Deutsch C, Krause N, Lipshutz BH. CuH-Catalyzed Reactions. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2916–2927. doi: 10.1021/cr0684321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hughes G, Kimura M, Buchwald SL. Catalytic Enantioselective Conjugate Reduction of Lactones and Lactams. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11253–11258. doi: 10.1021/ja0351692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowlan DT, III, Singleton DA. Mechanism and Origin of Enantioselectivity in the Rh2(OAc)(DPTI)3-Catalyzed Cyclopropenation of Alkynes. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6190–6191. doi: 10.1021/ja0504441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe N, Ogawa T, Ohtake Y, Ikegami S, Hashimoto S. Dirhodium(II) Tetrakis[N-Phthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate]: A Notable Catalyst for Enantiotopically Selective Aromatic Substitution Reactions of α-Diazocarbonyl Compounds. Synlett. 1996;1996:85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goto T, Takeda K, Anada M, Ando K, Hashimoto S. Enantio- and Diastereoselective Cyclopropanation with tert-Butyl α-Diazopropionate Catalyzed by Dirhodium(II) Tetrakis[N-tetrabromophthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:4200–4203. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto S, Watanabe N, Sato T, Shiro M, Ikegami S. Enhancement of Enantioselectivity in Intramolecular C-H Insertion Reactions of α-Diazo-β-Keto Esters Catalyzed by Chiral Dirhodium(II) Carboxylates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:5109–5112. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindsay VNG, Lin W, Charette AB. Experimental Evidence for the All-Up Reactive Conformation of Chiral Rhodium(II) Carboxylate Catalysts: Enantioselective Synthesis of Cis-Cyclopropane α-Amino Acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16383–16385. doi: 10.1021/ja9044955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeAngelis A, Boruta DT, Lubin JB, Plampin JN, III, Yap GPA, Fox JM. The Chiral Crown Conformation in Paddlewheel Complexes. Chem Commun. 2010;46:4541–4543. doi: 10.1039/c001557a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindsay VNG, Nicolas C, Charette AB. Asymmetric Rh(II)-Catalyzed Cyclopropanation of Alkenes with Diacceptor Diazo Compounds: p-Methoxyphenyl Ketone as a General Stereoselectivity Controlling Group. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8972–8981. doi: 10.1021/ja201237j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghanem A, Gardiner MG, Williamson RM, Müller P. First X-ray Structure of a N-Naphthaloyl-Tethered Chiral Dirhodium(II) Complex: Structural Basis for Tether Substitution Improving Asymmetric Control in Olefin Cyclopropanation. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:3291–3295. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goto T, Takeda K, Shimada N, Nambu H, Anada M, Shiro M, Ando K, Hashimoto S. Highly Enantioselective Cyclopropenation Reaction of 1-Alkynes with α-Alkyl- α-Diazoesters Catalyzed by Dirhodium(II) Carboxylates. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:6803–6808. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Reger DL, Horger JJ, Smith MD. Copper(II) Carboxylate Tetramers Formed from an Enantiopure Ligand Containing a π-Stacking Supramolecular Synthon: Single-Crystal to Single-Crystal Enantioselective Ligand Exchange. Chem Commun. 2011;47:2805–2807. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04797j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reger DL, Horger JJ, Debreczeni A, Smith MD. Syntheses and Characterization of Copper(II) Carboxylate Dimers Formed from Enantiopure Ligands Containing a Strong Stacking Synthon: Enantioselective Single-Crystal to Single-Crystal Gas/Solid-Mediated Transformations. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:10225–10240. doi: 10.1021/ic201238n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller P, Allenbach Y, Robert E. Rhodium(II)-catalyzed Olefin Cyclopropanation with the Phenyliodonium Ylide Derived from Meldrum’s Acid. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:779–785. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson RW, Manske RH. The Reaction Products of Indols with Diazoesters. Can J Res. 1935;13b:170–174. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lian Y, Davies HML. Rhodium-catalyzed [3+2] Annulation of Indoles. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:440–441. doi: 10.1021/ja9078094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie Q, Song X-S, Qu D, Guo L-P, Xie Z-Z. DFT Study on the Rhodium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization of Indoles: Enol versus Oxocarbenium Ylide. Organometallics. 2015;34:3112–3119. [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) Ito M, Kondo Y, Nambu H, Anada M, Takeda K, Hashimoto S. Diastereo- and Enantioselective Intramolecular 1,6-C–H Insertion Reactions of α-Diazo Esters Catalyzed by Chiral Dirhodium(II) Carboxylates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:1397–1400. [Google Scholar]; (b) Goto T, Onuzuka T, Kosaka Y, Andada M, Takeda K, Hashimoto S. Catalytic Asymmetric Intermolecular C–H Insertion of 1,4-Cyclohexadiene with α-alkyl-α-diazoesters using Chiral Dirhodium (II) Carboxylates. Heterocycles. 2012;86:1647–1659. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walczak MAA, Krainz T, Wipf P. Ring-Strain-Enabled Reaction Discovery: New Heterocycles from Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1149–1158. doi: 10.1021/ar500437h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin C, Davies HML. Enantioselective Synthesis of 2-Arylbicyclo[1.1.0]butane Carboxylates. Org Lett. 2013;15:310–313. doi: 10.1021/ol303217s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panish R, Chintala SR, Boruta DT, Fang Y, Taylor MT, Fox JM. Enantioselective Synthesis of Cyclobutanes via Sequential Rh-catalyzed Bicyclobutanation/Cu-catalyzed Homoconjugate Addition. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9283–9286. doi: 10.1021/ja403811t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]