Abstract

Mechanical properties of the microenvironment regulate cell morphology and differentiation within complex organs. However, methods to restore morphogenesis and differentiation in organs in which compliance is suboptimal are poorly understood. We used mechanosensitive mouse salivary gland organ explants grown at different compliance levels together with deoxycholate extraction and immunocytochemistry of the intact, assembled matrices to examine the compliance-dependent assembly and distribution of the extracellular matrix and basement membrane in explants grown at permissive or non-permissive compliance. Extracellular matrix and basement membrane assembly were disrupted in the glands grown at low compliance compared to those grown at high compliance, correlating with defective morphogenesis and decreased myoepithelial cell differentiation. Extracellular matrix and basement membrane assembly as well as myoepithelial differentiation were restored by addition of TGFβ1 and by mechanical rescue, and mechanical rescue was prevented by inhibition of TGFβ signaling during the rescue. We detected a basal accumulation of active integrin β1 in the differentiating myoepithelial cells that formed a continuous peripheral localization around the proacini and in clefts within active sites of morphogenesis in explants that were grown at high compliance. The pattern and levels of integrin β1 activation together with myoepithelial differentiation were interrupted in explants grown at low compliance but were restored upon mechanical rescue or with application of exogenous TGFβ1. These data suggest that therapeutic application of TGFβ1 to tissues disrupted by mechanical signaling should be examined as a method to promote organ remodeling and regeneration.

1. Introduction

Cell and organ development are mechanosensitive [1–5], yet the cellular and molecular mechanisms through which mechanical signaling is transmitted throughout organs and sensed by the cells is not well understood. The majority of mechanobiology research has utilized isolated cell lines, which has set a foundation to investigate the mechanically regulated pathways. Although these studies have provided insight into cellular signals that may play a larger role in tissue development, they do not address complex multicellular and tissue-level responses to compliance changes. Many pathologic conditions, such as specific solid tumors and fibrosis, are characterized by high stiffness (low compliance), due to excess deposition and assembly of the extracellular matrix [6,7]. Therapeutic options are needed to restore normal tissue structure in such situations in which compliance has been disrupted. Since the developing embryonic mouse submandibular salivary gland (mSMG) is mechanosensitive [8–10], it is a useful model system for investigating mechanical signaling in the context of a 3D organ. We previously demonstrated that polyacrylamide (PA) gels of a high compliance that is similar to embryonic in vivo tissue (Young’s modulus of approximately 0.5 kPa), are permissive for branching morphogenesis and epithelial differentiation of embryonic mouse submandibular salivary glands (mSMG) organ explants [9,11], whereas low-compliance PA gels more similar to pathological stiffness (20 kPa) are non-permissive for mSMG branching morphogenesis and epithelial differentiation. Permissive (0.5 kPa) compliance allows extensive elaboration of the mSMG epithelium by branching morphogenesis with development of fairly uniform bi-layered proacini characterized by the expression and interior localization of the secretory acinar protein, aquaporin 5, and the exterior localization of the myoepithelial protein, smooth muscle alpha-actin (SM α-actin) [9,12]. In contrast, explants grown on PA gels with non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance demonstrated aberrant morphogenesis characterized by a distorted and non-uniform epithelial structure. The well-ordered bi-layered acinar morphology was lost in the epithelium, with a profound loss of SM α-actin in the myoepithelial precursor cells at the epithelial periphery and disorganized aquaporin 5-expressing proacinar cells. Significantly, defective proacinar morphogenesis and differentiation at non-permissive low compliance were robustly rescued with transfer of the explants to permissive high compliance gels, “mechanical rescue,” and were partially rescued by addition of exogenous TGFβ1 to the non-permissive cultures, “TGFβ/chemical rescue”. These rescues demonstrate that the organ is still plastic at this stage of development and that the aberrant compliance-dependent development is reversible.

In the developing mSMG, invaginations of the basement membrane, or clefts, initiate branching morphogenesis at the embryonic day 12 (E12) time point to divide the initial, non-differentiated epithelial bud into multiple buds and promote the formation of secretory acini. The extracellular matrix (ECM) and basement membrane are dynamically assembled during the process of branching morphogenesis, involving the interplay of stromal and epithelial compartments. Dynamic basement membrane assembly and positioning are crucial to cleft initiation and progression for the elaboration of salivary gland structure during branching morphogenesis [13–17]. Collagen I, which is produced by the stromal compartment of the mSMG [18] is required to promote branching morphogenesis in mouse salivary glands [18–20]. Although TGFβ promotes matrix deposition and assembly, and TGFβ signaling exhibits extracellular compliance-dependent regulation of the production and assembly of ECM proteins [21–23], whether TGFβ-mediated signaling is required for modulation of ECM and basement membrane in developing salivary glands has not been examined. TGFβ superfamily members are known to be involved in the branching morphogenesis and differentiation of several exocrine glands, including salivary glands reviewed in [24]. TGFβ1 deficiency can interfere with later stages of wound healing in multiple organs [25] and female conditional knockout TGFβR1 mice develop an aberrant acinar morphology associated with an inflammatory disease in the salivary glands and other organs [26]. MMTV-driven overexpression of active TGFβ1 in the salivary glands of β1glo/MC mice resulted in death of most pups that had malformed salivary glands due to decreased branching morphogenesis and an increased fibrotic mesenchyme. Those animals that survived to adulthood suffered hyposalivation due to acinar atrophy and salivary gland fibrosis [27]. Thus, both ECM and TGFβ signaling are critical to salivary gland development.

In this study, we have used mSMG organ explants as an ex vivo model to examine the ability of TGFβ signaling to overcome compliance-dependent changes in the assembly of the ECM and basement membrane that may be used to guide future efforts in tissue regeneration.

2. Results

2.1 TGFβ signaling is required for mechanical rescue of mSMG development

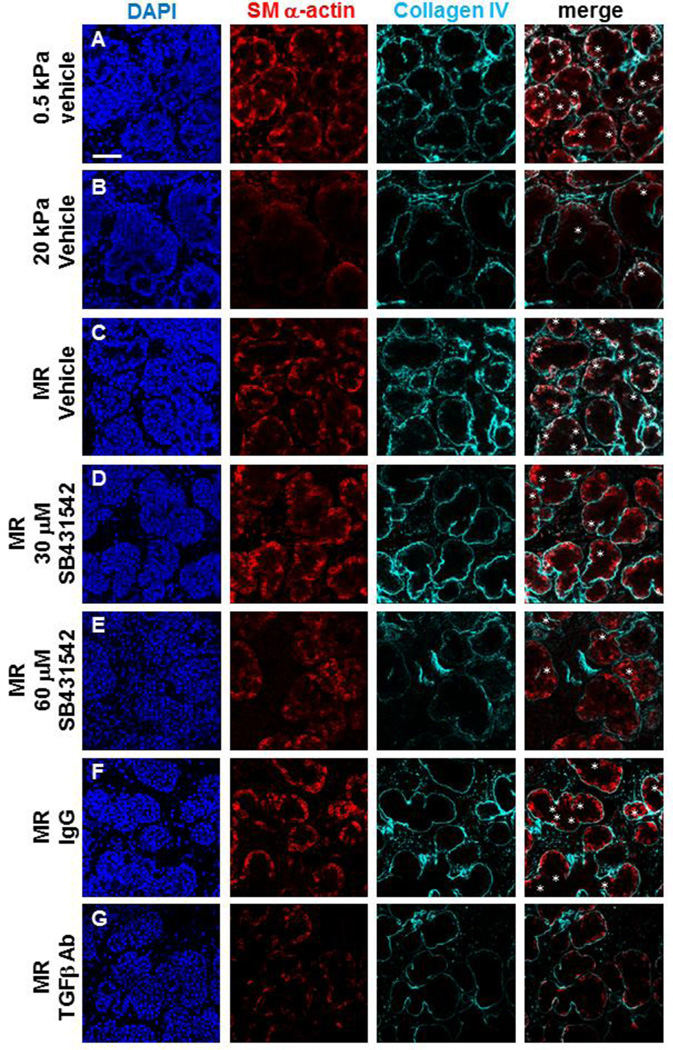

Since addition of exogenous TGFβ can partially rescue compliance-dependent mSMG development [9], we questioned if TGFβ signaling is required for the mechanical rescue of gland morphology and myoepithelial differentiation that occurs when glands cultured at nonpermissive compliance (20 kPa) for 72 hours are transferred to permissive compliance (0.5 kPa) for 24 hours. We inhibited TGFβ pathway signaling using the pharmacological inhibitor SB431542 that selectively inhibits TGFβ receptor I (TGFβRI)/activin receptor-like kinase 5 (ALK5) and the related receptors ALK4 and ALK7 [28–31] during the 24 hours of growth on 0.5 kPa gels following 72 hours of growth on 20 kPa polyacrylamide gels in control media. Additionally, we used a pan TGFβ blocking antibody to interfere specifically with the function of the TGFβ ligands relative to a matched isotype control. Immunocytochemical analysis and confocal imaging of organ explants revealed that both SB431542 (Figure 1 D, E) and the pan-TGFβ function blocking antibody (Figure 1G) impaired the rescue of bi-layered proacini characterized by expression of the developing myoepithelial cell marker SM α-actin at the epithelial bud peripheries relative to controls (Figure 1 C, F). To determine if TGFβ signaling is likely to be required for SMG development under in vivo-like compliance conditions, we also inhibited TGFβ signaling using SB431542 on glands grown on 0.5 kPa polyacrylamide gels (Supp. Figure 1). Relative to controls, inhibition of TGFβ signaling in explants on permissive (0.5 kPa) gels caused a reduction of SM α-actin positive differentiating myoepithelial cells indicative of bilayered acinar formation together with disruption in tissue structure that was similar to that in explants grown on non-permissive (20 kPa) gels. Together, these data demonstrate that TGFβ signaling promotes myoepithelial differentiation and bi-layered acinar morphogenesis during normal ex vivo development and during mechanosensitive salivary gland restoration.

Figure 1. TGFβ signaling is required for rescue of mechanosensitive SMG development.

(A–G) Representative single confocal images captured from the center of the organ explants cultured for 96 hours show representative proacinar morphology, as detected by DAPI staining and ICC for collagen IV (cyan) for basement membrane and SM α-actin (red) for myoepithelial cell differentiation, as detected by ICC in single confocal images. (A) Proacinar structures in SMG grown on permissive (0.5 kPa) gels show uniform epithelial buds with SM α-actin (red) expressed in the outer differentiating myoepithelial cell populations surrounded by basement membrane, indicated by collagen IV (cyan). White asterisks indicate regions where collagen IV in ingressing clefts is associated with SM α-actin. (B) SMG grown on non-permissive (20 kPa) gels exhibit non-uniform distorted epithelial buds with a profound loss of SM α-actin and clefts. (C) Mechanical rescue (MR) restores epithelial bud morphology, clefting, and SM α-actin (red) expressed in the outer differentiating myoepithelial cells. (D–E) Inhibition of TGFβ receptor signaling with SB431542 during the MR reduces levels of SM α-actin and clefts. (F–G) Control IgG does not prevent MR, but inhibition of TGFβ signaling with function blocking antibody during the MR reduces levels of SM α-actin and clefts. n=3 experiments. Scalebar = 50 µm.

2.2 TGFβ signaling promotes ECM and basement membrane assembly during chemical and mechanical rescues of mSMG development

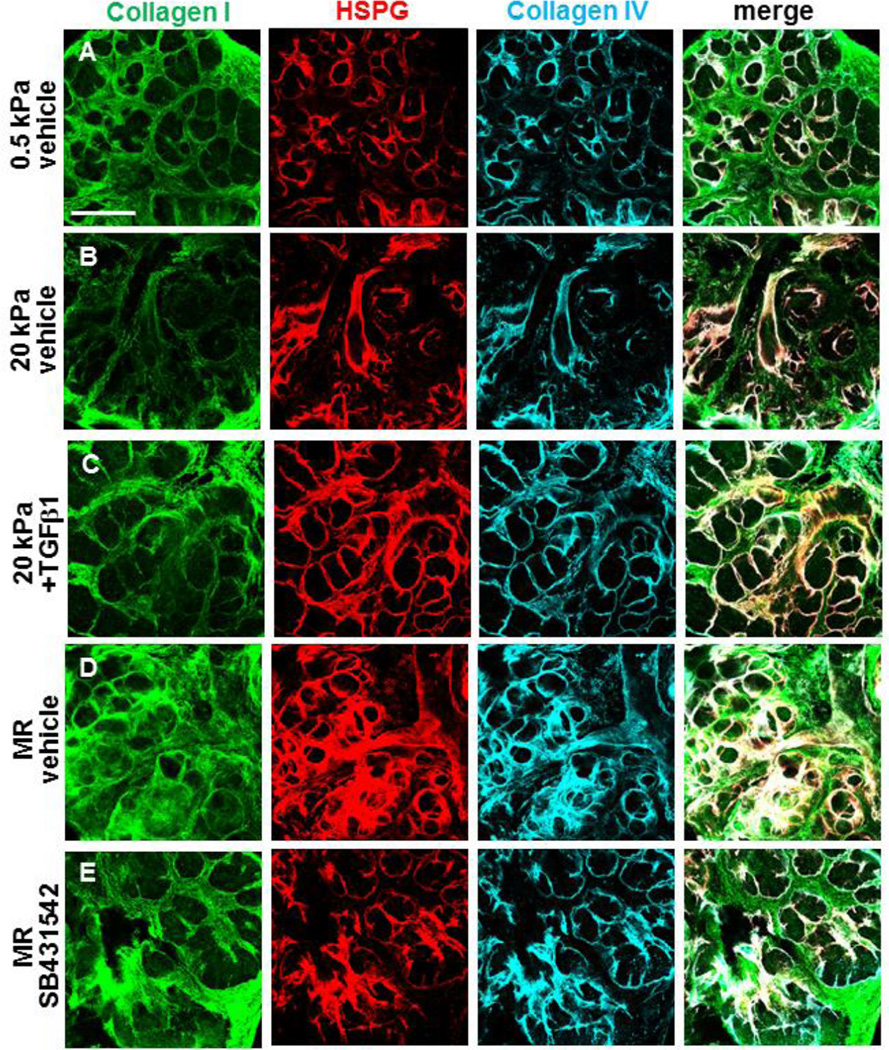

Given that TGFβ1 is known to regulate ECM and basement membrane assembly, we examined the assembled ECM and basement membrane in this ex vivo mechanosensitive gland restoration system. We used deoxycholate (DOC) extraction and confocal ICC to specifically examine changes in the assembled fractions of ECM/basement membrane components, as unassembled matrix proteins are solubilized under these conditions leaving only the intact, assembled matricellular protein arrays [32,33]. We assayed collagen I to detect assembled ECM, and collagen IV and heparin sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) to detect assembled basement membrane (Figure 2). In mSMG explants cultured at permissive (0.5 kPa) compliance, we noted collagen I assembled throughout the stroma and assembled basement membrane displaying a regular pattern with collagen IV and HSPG encircling the developing epithelial structures (Figure 2A). In contrast, glands grown at non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance demonstrated reduced levels of assembled collagen I in the ECM as well as disruption of assembled collagen IV and HSPG in the basement membrane (Figure 2B). Strikingly, both TGFβ1-mediated (Figure 2C) and mechanical (Figure 2D) rescues stimulated increased levels of assembled ECM and basement membrane. To examine a TGFβ-dependence for the mechanical rescue, we used the inhibitor SB431542. Inclusion of SB431542 to block TGFβR1 signaling during the mechanical rescue phase decreased the assembled basement membrane and led to heterogeneity within the assembled collagen I extracellular matrix during mechanical rescue (Figure 2E). These data indicate that the assembled ECM and basement membrane are disrupted in glands grown at low (nonpermissive) compliance, that both the TGFβ-mediated rescue and mechanical rescue restore assembled ECM/basement membrane, and that restoration of matrix assembly during mechanical rescue requires TGFβ signaling.

Figure 2. TGFβ signaling promotes ECM and basement membrane assembly during rescue of mechanosensitive SMG development.

(A–E) Glands were cultured on PA gels +/− rescue conditions, +/− TGFβ1, and +/− SB431542 for 96 hours and were subsequently subjected to DOC-extraction and ICC to detect assembled collagen I (green), collagen IV (cyan), and HSPG (red) in single confocal images. (A) Assembled collagen I (green) in the stroma surrounds the epithelial buds and secondary lobules, or groups of proacini, in glands cultured at permissive (0.5 kPa) compliance. Basement membrane proteins, HSPG and collagen IV, are assembled in uniform layers around proacinar buds. (B) Both primary and secondary networks of assembled collagen I and basement membrane are disrupted in glands cultured at non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance. (C) Addition of 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 to the media of glands grown on 20 kPa gels stimulates a rescue of ECM and BM proteins together with improved proacinar morphology. (D) Mechanical rescue (MR) of the glands demonstrates elevated levels of collagen I in the stroma and increased HSPG and collagen IV encasing proacini. (E) Inhibition of TFGβ receptor signaling with 60 µM SB431542 disrupts the collagen re-patterning, with clefts initiating but not progressing as well as with MR (D). n=3 experiments. Scalebar = 250 µm.

2.3 TGFβ signaling promotes ECM/basement membrane assembly and cleft progression during rescues of mechanosensitive SMG development

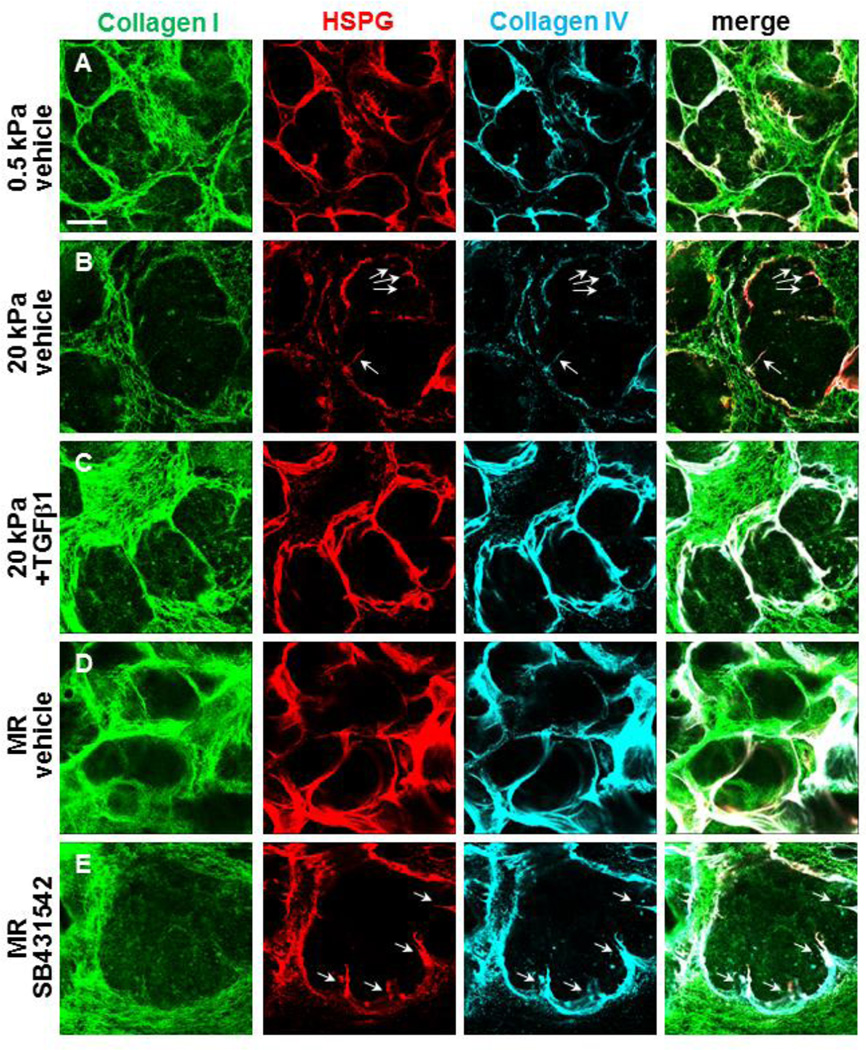

Since cleft formation is required for branching morphogenesis, we used high magnification imaging of the assembled matrices in the DOC-extracted glands to examine clefts within developing proacini. Figure 3A demonstrates several clefts in glands grown at permissive (0.5 kPa) compliance with ECM/basement membrane proteins ingressing into the clefts. However, the penetration of ECM/basement membrane proteins into clefts within glands grown at nonpermissive (20 kPa) compliance is reduced relative to glands grown on 0.5 kPa gels. These clefts appear to have stalled and fail to divide the epithelium into smaller buds (Figure 3B, white arrows). Significantly, both the TGFβ-mediated (Figure 3C) and mechanical (Figure 3D) rescues demonstrate increased levels of assembled ECM/basement membrane penetrating clefts and dividing the existing buds into multiple smaller proacini; blocking TGFβ signaling with SB431542 prevents cleft progression and budding in the mechanical rescue (Figure 3E, white arrows). The TGFβ-dependent ECM/basement membrane assembly during completion of clefting and subdivision of the epithelium can also be visualized using serial confocal imaging (Figure 4). Here, serial images track the 3D progression of assembled matrix proteins into clefts in explants grown at permissive (0.5 kPa) compliance (Figure 4A), but no cleft progression is detected in glands grown at non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance (Figure 4B); TGFβ (Figure 4C) and mechanical (Figure 4D) rescues restore 3D assembled matrix in progressing clefts, which is blocked by inhibition of TGFβ receptor signaling during the mechanical rescue (Figure 4E). These data show that both TGFβ-mediated chemical rescue and TGFβ-dependent mechanical rescues restore assembled ECM and basement membrane with cleft progression and promote epithelial morphogenesis and differentiation.

Figure 3. TGFβ signaling promotes cleft progression and elaboration of proacinar structures during rescue.

(A–B) Glands were cultured on PA gels +/− rescue conditions and +/− TGFβ1 or SB431542 for 96 hours and subsequently subjected to DOC-extraction and ICC to detect assembled collagen I (green), collagen IV (cyan), and HSPG (red) in single confocal images, as in Figure 2. (A) Multiple clefts ingressing into proacini are apparent. (B) Assembled collagen I at non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance is greatly reduced relative to permissive (0.5 kPa) compliance. Basement membrane assembly around proacinar bud regions is less contiguous at 20 kPa, with clefts failing to progress and divide the enlarged bud region, shown by the white arrows. (C) Addition of 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 to the media of glands grown at kPa, increased levels of assembled stromal collagen I and HSPG and collagen IV in the basement membrane around buds and deeper clefts completing bud division into smaller bud units. (D) Mechanical rescue (MR) restores assembled collagen I in the stroma and HSPG and collagen IV in the basement membrane. (E) Inhibition of TGFβ1 with 60 µM SB431542 disrupts ECM and basement membrane assembly, with failure in cleft progression detected (white arrows). n=3 experiments. Scalebar = 50 µm.

Figure 4. TGFβ receptor signaling promotes progression of basement membrane proteins into bud regions to complete clefting.

(A–E) Glands were cultured on PA gels +/− rescue conditions and +/− TGFβ1 or SB431542 for 96 hours under the following conditions: (A) 0.5 kPa, (B) 20 kPa, (C) 20 kPa + 5 ng/ml TGFβ1, (D) Mechanical rescue, defined as growth for 72 hours on 20 kPa gels followed by 24 hours growth on 0.5 kPa gels, and (E) Mechanical rescue + 60 µM SB431542. Glands were subsequently subjected to DOC-extraction and ICC to detect assembled collagen I (green), collagen IV (cyan), and HSPG (red) in sequential single section confocal images. Images are derived from Figure 3, with 1 µm distance between each slice. Dotted boxes surround equivalent clefting regions. Clefts progress and divide the bud into smaller buds when cultured on 0.5 kPa gels, when stimulated with TGFβ1, or when subjected to mechanical rescue (A, C, and D). Growth on 20 kPa gels or inhibition of mechanical rescue with 60 µM SB431542 results in thin, shallow clefts that fail to subdivide the bud (B and E). n=3 experiments. Scalebar = 50 µm.

2.4 TGFβ receptor signaling promotes integrin β1 activation in basal epithelial cells during rescue

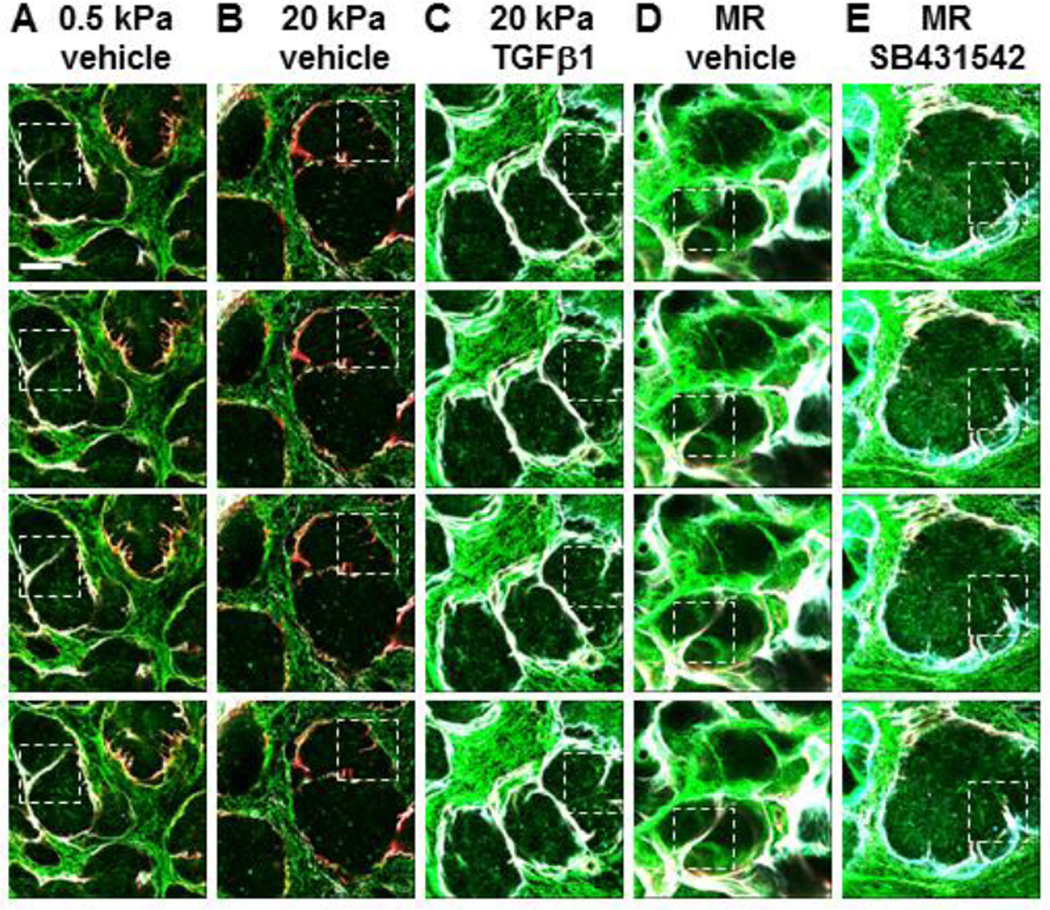

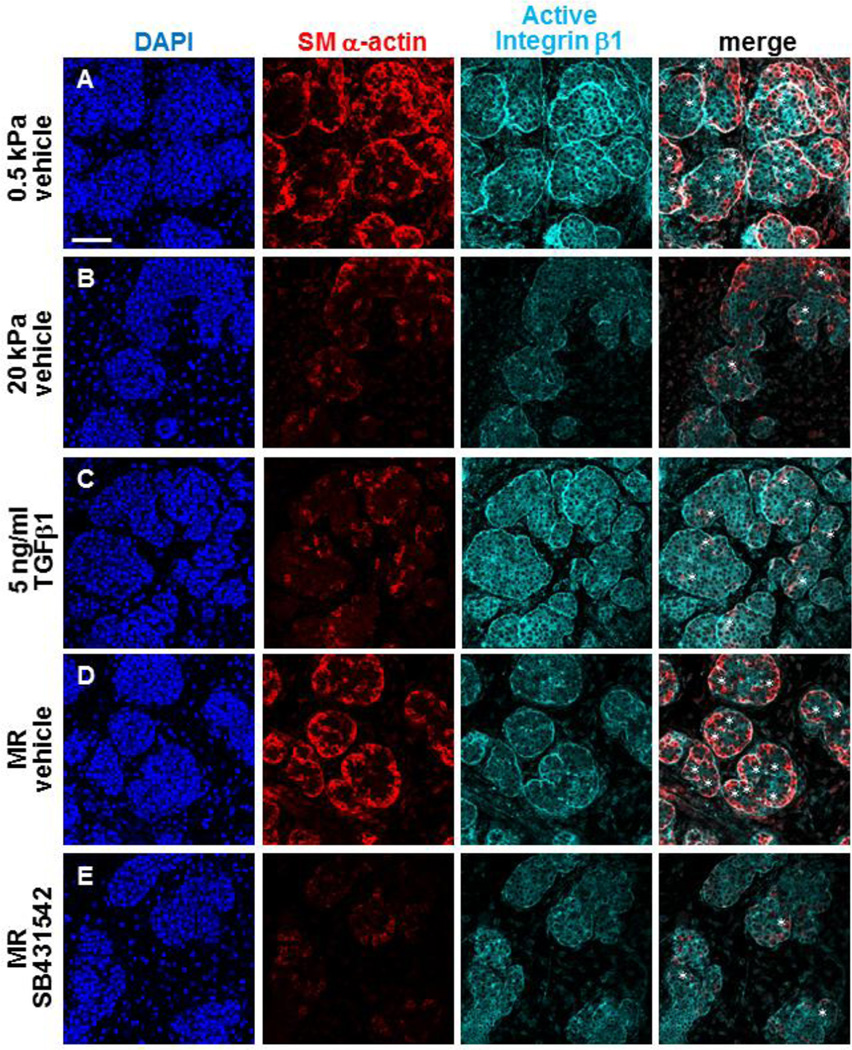

Integrins are known to function as mechanotransducing receptors, linking extracellular matrices with intracellular cytoskeletal signaling [34–37]. Integrin β1 was previously shown to be required for mSMG branching morphogenesis [15], and active integrin β1 was detected in clefts and at the basal periphery of glands undergoing branching morphogenesis [14]. To determine whether integrin β1 is a potential sensor of mechanical signaling in the developing mSMG epithelium, we performed ICC and confocal imaging to detect active integrin β1, utilizing the 9EG7 clone that detects activated integrin β1 [38], in glands grown on 0.5 and 20 kPa gels (Figure 5A,B). Relative to permissive (0.5 kPa) gels, we found a decrease in active integrin β1 immunoreactive with 9EG7 in glands cultured at non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance with a disruption in the continuous localization of the active integrin β1 at the outer periphery of the proacinar buds (Fig. 5B). Additionally, the number of clefts was dramatically reduced in glands cultured at nonpermissive (20 kPa) compliance (Figure 5B). To determine if TGFβ1 could stimulate integrin β1 activation, we treated glands grown at non-permissive compliance (20 kPa) with exogenous TGFβ1. TGFβ1 stimulated activation of integrin β1 that was localized at the periphery of the basal epithelial cells and associated with increased SM α-actin levels in these developing myoepithelial cells (Figure 5C). Relative to controls (Figure 5D), disruption of TGFβ1 signaling in glands subjected to mechanical rescue with SB431542 (Figure 5E) prevented the localized activation of integrin β1 within the proacinar periphery.

Figure 5. TGFβ signaling promotes integrin β1 activation during rescue.

(A–E) Explants were cultured on PA gels +/− rescue conditions and +/− SB431542 for 96 hours. DAPI (blue), active integrin β1 (cyan), and myoepithelial differentiation (SM α-actin,red) were detected by ICC in single confocal images. Asterisks indicate clefting regions with active integrin β1 and SM α-actin in the region. (A) Epithelial buds are uniform at permissive (0.5 kPa) compliance with SM α-actin (red) restricted to the outside of the proacini. (B) Explants cultured at non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance show less uniform structure with reduced active integrin β1 around bud peripheries and SM α-actin, with a reduction in clefting. (C) Addition of TGFβ1 to glands on 20 kPa gels partially rescues SM α-actin expression in the outer regions of more uniform proacinar buds, along with increased active integrin β1 throughout the epithelial buds. (D) Mechanical rescue (MR) restores robust SM α-actin expression in the outer regions of more uniform proacinar buds, along with increased active integrin β1 at the bud peripheries and in clefts. (E) Inhibition of TGFβ receptor signaling with 60 µM SB431542 during the 24 hour mechanical rescue conditions prevents rescue of the active integrin β1 around proacinar structures and in clefting regions, concomitant with reduction of SM α-actin in clefts. n=3 experiments. Scalebar = 50 µm.

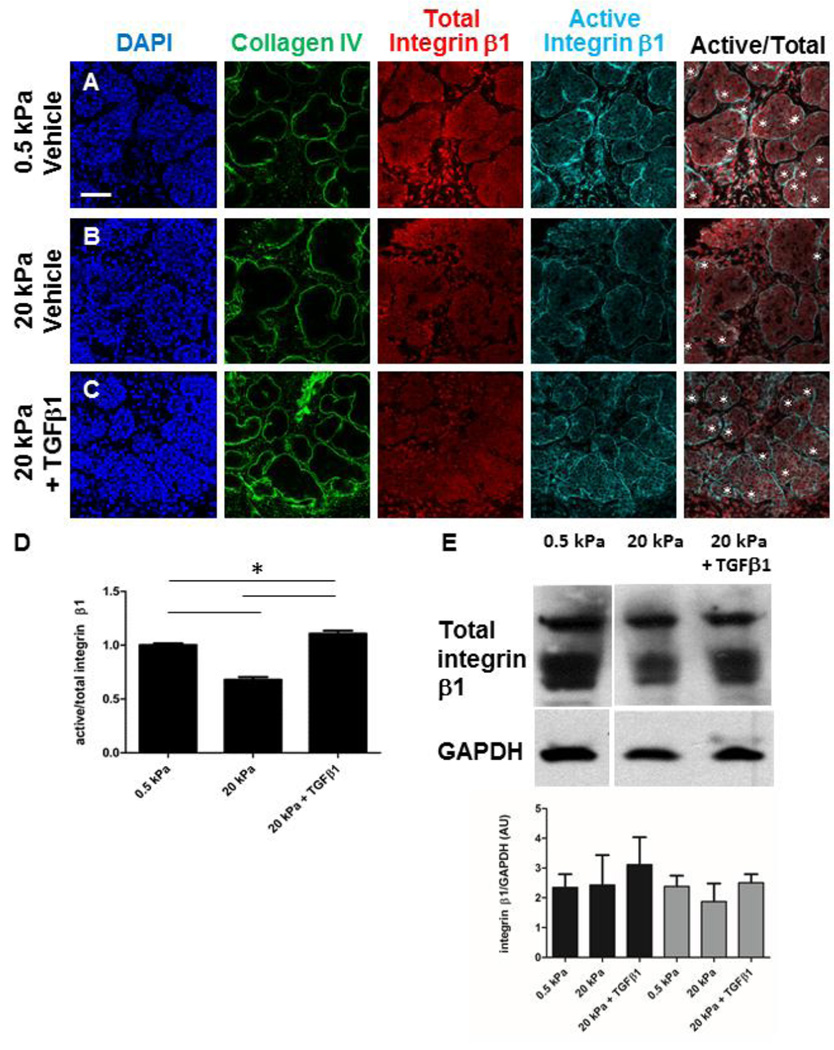

TGFβ1 rescue of active integrin β1 in glands cultured at abnormal compliance could be due to activation of integrin β1 or to modulation of total integrin levels. We performed quantitative ICC to detect total integrin β1 together with active integrin β1 in glands grown at permissive (0.5 kPa) and non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance, as well as with TGFβ rescue (Figure 6). Interestingly, we found that while the ratio of active/total integrin β1 was significantly reduced in glands cultured at non-permissive versus permissive compliance, exogenous TGFβ1 stimulated the activation of integrin β1 even above levels detected in glands grown at permissive compliance (Figure 6D). Western analysis of whole glands from these conditions indicated that the total levels of integrin β1, although heterogeneous, were not significantly altered by compliance or by TGFβ stimulation (Figure 6E). Together, these data indicate that integrin β1 activation is mechanosensitive, and that TGFβ can rescue integrin β1 activation in glands grown at non-permissive compliance at the epithelial basal periphery and in cleft regions where basement membrane is assembled.

Figure 6. Compliance-dependent activation of integrin β1 within the epithelium is modulated by TGFβ Signaling.

(A–E) Explants were cultured on for 96 hours on 0.5 kPa gels, 20 kPa gels or 20 kPa gels + TGFβ1. Representative single confocal images of explants subjected to ICC to detect collagen IV (green) and DAPI (blue), total integrin β1 (red), and active integrin β1 (mAb9EG7) (cyan), with white asterisks denoting clefting regions in the merged panel. (A) In glands at permissive (0.5 kPa) compliance, total integrin β1 was detected in all cells, with active levels preferentially localizing to the bud periphery and clefts in proacini, demonstrated by white asterisks. (B) In explants grown at non-permissive (20 kPa) compliance, total integrin β1 is not obviously altered, while active integrin β1 is reduced around the bud peripheries and in clefting regions. (C) Total integrin β1 is not significantly altered by addition of 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 at 20 kPa, but levels of active integrin β1 are increased in the outer peripheries and in clefting regions. n=3 experiments. Scalebar = 50 µm. (D) Quantification of active versus total integrin β1 reveals that the ratio of active to total integrin β1 is significantly reduced at non-permissive compliance, and is restored by TGFβ rescue. A one-way ANOVA test indicates a significant difference between groups indicated (* p < 0.05), n=14 glands. (E) Western analysis of total integrin β1 from the experimental conditions depicted in A–C, with several bands representing glycosylated forms. Quantification of the western analysis to detect the total integrin β1 levels, with total pixel levels for the top single band and the bottom double bands separately normalized to GAPDH and expressed as arbitrary units (AUs). A one-way ANOVA test indicates no significant difference between any of the conditions (p > 0.05), n=3 experiments.

3. Discussion

We here demonstrate a requirement for TGFβ signaling in mechanically dependent tissue restoration that involves ECM and basement membrane remodeling. In contrast to salivary gland organ explants grown on permissive substrates (0.5 kPa polyacrylamide gels), explants grown on non-permissive substrates (20 kPa gels), poor proacinar morphology and myoepithelial cell differentiation was associated with disrupted ECM and basement membrane assembly. ECM and basement membrane were restored with mechanical rescue of glands grown at non-permissive compliance by transfer to a permissive compliance. Restoration of acinar morphogenesis and myoepithelial differentiation was also partially restored with exogenous TGFβ1, which correlated with restoration of assembled ECM and basement membrane assembly. Additionally, mechanical rescue was dependent on TGFβ signaling, as demonstrated by SB431542 inhibition. Permissive compliance and TGFβ-dependent ECM/basement membrane assembly encircling the developing epithelium correlated with branching morphogenesis, bi-layered acinar formation, myoepithelial differentiation, and the activation of integrin β1 within the epithelium adjacent to sites of basement membrane assembly and in clefts, where active morphogenesis is occurring. Our data suggest that therapeutic application of TGFβ1 to embryonic tissues disrupted by mechanical signaling should be examined as a method to promote organ remodeling and regeneration.

Since we used the pharmacological inhibitor SB431542 to demonstrate the dependence of the “mechanical” rescue of ECM/basement membrane assembly on TGFβ signaling, we cannot rule out contributions from ALK4 and ALK7 receptors in addition to ALK5. However, the similarity of the pan-TGFβ ligand function blocking antibodies for disruption of “mechanical” rescue together with the ability of TGFβ to “chemically” rescue gland development and ECM/basement membrane assembly, confirm a requirement for TGFβ signaling for compliance-dependent gland development and ECM/basement membrane assembly.

Our finding that the assembly of both the stromal ECM and the epithelial basement membrane are compliance-dependent in embryonic salivary glands is consistent with other reports demonstrating that ECM production by mesenchymal cells is mechanically dependent [39–44]. However, it is not clear whether the compliance-dependent and TGFβ-dependent changes in assembled ECM and basement membrane that we report here are primarily due to changes in protein expression levels, matrix assembly, and/or proteolytic degradation. Since substrate compliance correlates with the ability of lung alveolar epithelial cells to assemble laminin and fibronectin [45], ECM and basement membrane assembly may be affected in this context as well. Our data are consistent with findings from our lab and others indicating that basement membrane assembly is mechanically sensitive and is required to initiate clefting and promote branching morphogenesis in the mSMG [14–16,46], mammary gland [47,48], and lung [49,50]. Additionally, assembly of ECM and basement membrane may be required for myoepithelial cell morphogenesis or differentiation in this context. Since myoepithelial cells produce and remodel basement membrane associated with improved acinar development in the mammary gland [47], the myoepithelial cells may additionally participate in compliance-dependent basement membrane assembly and remodeling. Thus, the combined actions of mesenchymal cells with the myoepithelial cell population may be required for compliance-dependent tissue remodeling during development and homeostasis of branched organs.

TGFβ signaling is known to be involved in branching morphogenesis. In the mouse salivary gland, single gene knockouts of TGFβ ligands do not prevent development [51], yet conditional overexpression of TGFβ1 leads to increased mesenchyme, acinar atrophy, and abnormally high collagen deposition [27]. Thus, proper regulation of TGFβ signaling is critical for development and tissue homeostasis. In other contexts, TGFβ stimulates expression of ECM proteins during development [27,52–54] and in wound healing, which when excessive can lead to a fibrotic response in multiple organs [55–63] and induce epithelial-mesenchymal transitions [64–68]. In the mammary gland, TGFβ regulation of branching morphogenesis via matrix dynamics requires epithelial-stromal collaboration and is cell-type specific [53,60,69]. Cell differentiation of isolated, mixed adult salivary gland mesenchymal and epithelial populations in an in vitro culture system were inversely affected by TGFβ stimulation or receptor inhibition [70], consistent with other work indicating that effects of TGFβ are cell type and context dependent. The cell types that respond to TGFβ, the mechanisms by which TGFβ isoforms regulate salivary gland development and homeostasis, and how TGFβ activity is controlled during these processes, however, is unknown. Hence, defining the mechanisms of TFGβ signaling in complex tissues, while challenging, is essential to understand how TGFβ maintains normal tissue architecture and how dysregulation of TGFβ signaling contributes to diverse organ pathologies.

In embryonic mSMG explants cultured on non-permissive stiff substrates, release or activation of TGFβ from the ECM may be misregulated. Incorporation of latent TGFβ complexes into the ECM followed by proteolytic or integrin-mediated activation is important for proper TGFβ function [71–73], and impaired binding to the ECM results in aberrant TGFβ signaling [74–76]. The rapid, TGFβ-dependent mechanical rescue of assembled ECM/basement membrane suggests that rescue of substrate compliance may activate TGFβ-dependent ECM and basement membrane synthesis or assembly to promote branching morphogenesis and bi-layered acinar differentiation. Since manipulation of TGFβ signaling in the mesenchyme of developing mouse teeth indirectly regulates development of the epithelium [77], TGFβ regulation of the salivary epithelium may be mediated indirectly through the mesenchyme. Since TGFβ signaling is known to stimulate expression of myogenic genes and a myogenic phenotype in many contexts [78–81], direct TGFβ1 stimulation of the myoepithelial phenotype is also possible. Direct TGFβ stimulation of the myoepithelial cells may synergize with matrix assembly and remodeling by the mesenchyme cells for branching morphogenesis and/or cytodifferentiation. We propose that physiological compliance regulates TGFβ signaling in both the mesenchymal and epithelial populations. Compliance-dependent manipulation of TGFβ signaling in one or both of these compartments may interfere with epithelial morphogenesis and differentiation. Thus, to discern the mechanisms by which TGFβ functions in a cell type-specific manner within complex, intact organs will require targeted manipulation of TGFβ signaling in specific cell types.

Since integrins are well-established mechanotransduction receptors, integrin β1 may be activated by ECM- and basement membrane-dependent, outside-in signaling to transduce a mechanical signal from the ECM/basement membrane to the myoepithelial cell population. However, integrin β1 is also required for basement membrane assembly, and deficient insideout integrin β1 signaling leads to aberrant basement membrane assembly, often resulting in thinner and more disorganized basement membrane in developing salivary glands [82], similar to the compliance-and TGFβ-dependent mSMG effects in our work. Integrin β1-deficient SMGs also demonstrate aberrant differentiation and disrupted distribution of the acinar and mesenchymal populations, which may reflect interrupted communication between the epithelial and stromal compartments [82]. Our results show a correlation between TGFβ signaling, activation of integrin β1, basement membrane assembly, and differentiation of the myoepithelial cells in the developing bi-layered proacini, which is consistent with previous results showing expression of the myoepithelial differentiation markers CK14 and SM α-actin coincident with increased localization of integrin β1 [83], and suggesting that activation of integrin β1 may be required for myoepithelial cell differentiation. While we observed that activation of integrin β1 in myoepithelial regions can occur downstream of TGFβ-mediated signaling, multiple studies have shown that integrins can also activate TGFβ and alter downstream effects of TGFβ signaling [74] and [84]. The absence of integrin-mediated activation of TGFβ1 in mice in vivo leads to widespread defects similar to the TGFβ1-null mouse, indicating a primary role for integrin activation of TGFβ signaling pathways in developmental processes [73]. Our studies demonstrate that TGFβ-dependent restoration of mechanosensitive organ development may have utility in future tissue engineering and regenerative medicine approaches for restoration of gland function.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1 Polyacrylamide gels

Polyacrylamide gels were created by mixing specific ratios of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide according to established procedures [85] and attaching the gels to 12 mm round glass coverslips. To provide the organ explants with attachment sites, the gels were covalently linked to human plasma FN (Millipore, Billerica MA Cat No. FC010) with sulfo SANPAH (Thermo Scientific), as we reported previously [9].

4.2 Culture of whole and recombined submandibular salivary gland ex vivo organ explants on polyacrylamide gels

Mouse E13 SMGs were dissected from timed-pregnant female mice, strain CD-1 (Charles River Laboratories, city), with day of plug discovery designated as embryonic day 0 (E0). Explants were incubated on PA gels that were saturated with serum-free, phenol-free growth media (DMEM/Ham’s F12 media, 50:50 v/v) containing ascorbic acid (150 µg/ml) and transferrin (50 µg/ml) for 96 hours (DMEM/F12 complete media) in 24 well plates. Media, which surrounded the explants, was changed daily. For mechanical rescue experiments, explants were grown for 72 hours on 20 kPa PA gels, gently rinsed using DMEM/F12 to detach them from the gel, and then transferred with forceps to 0.5 kPa gels for an additional 24 hours. For growth factor rescue experiments, 20 kPa gels were saturated with 5 ng/ml of transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1) (R&D Systems) in DMEM/F12 complete media with 2 rinses of 500 µl of appropriate media for 1 hour at 37°C prior to culture of explants. Explants were saturated with growth factor for 90 min at room temperature prior to culture on the gels. For TGFβR inhibition, gels were saturated with DMEM/F12 complete media containing 30 or 60 µM SB431542 (Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) to selectively inhibit the activin receptor-like kinases (ALK)4, ALK5, and ALK7 [86]. Since SB431542 was resuspended in DMSO, all vehicle control glands in experiments including SB431542 were dosed with the vehicle, DMSO, in a volume equivalent to the 60 µM SB431542 volume. For mechanical rescue experiments with SB431542, glands were saturated with inhibitor-containing media or vehicle-containing media for 90 min prior to transfer to pre-saturated 0.5 kPa gels. PA gels are rinsed and saturated with appropriate media prior to the mechanical transfer. Pan-TGFβ ligand function blocking antibody experiments were done similar to SB431542 experiments, except using 100 µg/ml of clone 1D11 (eBioscience, San Diego CA and R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN) or 100 µg/ml of mouse IgG functional grade control antibody (eBioscience).

4.3 Whole mount immunocytochemistry (ICC), confocal imaging, and image quantification

SMGs were removed from gels and simultaneously fixed and permeabilized with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (w/v) (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) containing 5% sucrose (w/v) (Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 0.1% Triton X (Sigma) in 1X PBS for 20 minutes, rotating at room temperature, and processed for ICC, as previously described [10,87]. Explants were blocked for 1 hour in a 20% donkey serum, 3% BSA-PBST (w/v) solution containing 1 drop of mouse-on-mouse blocking reagent (MOM) (Vector Laboratories)/ml. All antibody incubations were performed in a solution of 10% BSA in PBST (w/v) with gentle rotation overnight at 4°C. SMGs were washed 4 × 15 minutes with rotation in 1X PBS containing 0.5% tween-20 (PBST) after each antibody incubation step and mounted on glass coverslips with Secure-Seal imaging spacers (Grace Bio-Labs, Bend OR) in 25 µl Fluoro-Gel (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Z stacks of organ explants were imaged on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany) or on a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope at 20× or 63× magnification. All confocal images shown are representative single sections from near the center of the explant. ICC and confocal imaging experiments were repeated at least three times to produce the representative composites.

Targets of antibodies used and their dilutions from stock solutions are as follows: Smooth Muscle Alpha Actin (SM α-actin)-Cy3 (clone 1A4) (1:200 dilution, Sigma Aldrich), Collagen IV (Col IV, 1:200 dilution, Millipore), Integrin β1 (1:100 dilution, Abcam), and Active Integrin β1 (clone 9EG7) (1:100 dilution, BD Biosciences). Cyanine, Dylight, and Alexa dye-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab’)2 fragments were used as secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Under the imaging conditions used, the secondary antibodies produced no signal in samples lacking primary antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Life Technologies) simultaneously with the secondary antibody incubation.

For image quantification of total integrin β1 and active integrin β1, three central slices distanced 1 µm apart were selected for each treatment from four to five explants each from three independent experiments, such that 42 images were quantified for each condition. Total pixel intensity was measured from each image using the FIJI version of ImageJ [88]. Values for active integrin β1 were divided by total integrin β1 and then normalized to permissive compliance values.

4.4 Sodium deoxycholate extraction of unassembled matrix proteins with ICC and confocal imaging of assembled matrices

Explants were submerged in 4% DOC in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, containing 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 mM EDTA, and a protease inhibitor tablet (per 10 mL DOC buffer) (Roche) in the well of the 24-well plate utilized for culturing. DOC solubilization was performed within 24-well plates that were gently rotated at 4°C for 90 minutes. The resulting DOC-insoluble matrices were fixed with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (w/v) (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) with 5% sucrose (w/v) (Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 20 minutes while rotating at room temperature, and processed for ICC and confocal imaging. Explants were washed gently 2 × 20 minutes with rotation in PBST after each antibody incubation step.

Targets of antibodies used and their dilutions from stock are as follows: collagen I (col I, 1:100 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), collagen IV (col IV, 1:200 dilution, Millipore), and the heparin sulfate proteoglycan, perlecan (HSPG) (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Cyanine, Dylight, and Alexa dye-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab’)2 fragments were used as secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA).

4.5 Immunoblotting

Protein concentration assays and Western blots were performed essentially as previously described [87]. Chemiluminescent blots were imaged using X-ray film and scanned using a flatbed scanner (CanoScan 4400F, Canon), and bands were quantified using Quantity One software (Version 19, BioRad), with normalization to GAPDH.

Targets of antibodies and their dilutions are as follows: Integrin β1 (1:500, Abcam), and GAPDH (1:20,000 dilution, Fitzgerald).

4.6 Statistical analysis

For organ explant Western analysis, a one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni post-tests were carried out for statistical analyses with Prism 5 software. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

ECM and basement membrane assembly are compliance-dependent.

TGFβ1 stimulates ECM/basement membrane restoration in a low compliance environment.

TGFβ signaling is required for mechanically dependent tissue restoration.

Exogenous TGFβ1 stimulates epithelial integrin β1 activation with tissue restoration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Livingston Van De Water and David Corr for helpful discussions. Supported by NIH/NIDCR R21DE02184101, R01DE022467, 1 C06 RR015464, and the New York Research Alliance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.DuFort CC, Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. Balancing forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:308–319. doi: 10.1038/nrm3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellas E, Chen CS. Forms, forces, and stem cell fate. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;31:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eyckmans J, Boudou T, Yu X, Chen CS. A hitchhiker’s guide to mechanobiology. Dev Cell. 2011;21:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janmey PA, Wells RG, Assoian RK, McCulloch CA. From tissue mechanics to transcription factors. Differentiation. 2013;86:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross TD, Coon BG, Yun S, Baeyens N, Tanaka K, Ouyang M, et al. Integrins in mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carver W, Goldsmith EC. Regulation of tissue fibrosis by the biomechanical environment. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:101979. doi: 10.1155/2013/101979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickup MW, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1243–1253. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyajima H, Matsumoto T, Sakai T, Yamaguchi S, An SH, Abe M, et al. Hydrogel-based biomimetic environment for in vitro modulation of branching morphogenesis. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6754–6763. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters SB, Naim N, Nelson DA, Mosier AP, Cady NC, Larsen M. Biocompatible Tissue Scaffold Compliance Promotes Salivary Gland Morphogenesis and Differentiation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daley WP, Gulfo KM, Sequeira SJ, Larsen M. Identification of a mechanochemical checkpoint and negative feedback loop regulating branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2009;336:169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosier A, Peters S, Larsen M, Cady N. Microfluidic Platform for the Elastic Characterization of Mouse Submandibular Glands by Atomic Force Microscopy. Biosensors. 2014;4:18–27. doi: 10.3390/bios4010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson DA, Manhardt C, Kamath V, Sui Y, Santamaria-Pang A, Can A, et al. Quantitative single cell analysis of cell population dynamics during submandibular salivary gland development and differentiation. Biol Open. 2013;2:439–447. doi: 10.1242/bio.20134309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daley WP, Gervais EM, Centanni SW, Gulfo KM, Nelson DA, Larsen M. ROCK1-directed basement membrane positioning coordinates epithelial tissue polarity. Development. 2012;139:411–422. doi: 10.1242/dev.075366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daley WP, Kohn JM, Larsen M. A focal adhesion protein-based mechanochemical checkpoint regulates cleft progression during branching morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:2069–2083. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakai T, Larsen M, Yamada KM. Fibronectin requirement in branching morphogenesis. Nature. 2003;423:876–881. doi: 10.1038/nature01712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen M, Wei C, Yamada KM. Cell and fibronectin dynamics during branching morphogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3376–3384. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daley WP, Yamada KM. ECM-modulated cellular dynamics as a driving force for tissue morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuda Y, Masuda Y, Kishi J, Hashimoto Y, Hayakawa T, Nogawa H, et al. The role of interstitial collagens in cleft formation of mouse embryonic submandibular gland during initial branching. Development. 1988;103:259–267. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardman P, Spooner BS. Alterations in biosynthetic accumulation of collagen types I and III during growth and morphogenesis of embryonic mouse salivary glands. Int J Dev Biol. 1992;36:423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spooner BS, Thompson-Pletscher HA, Stokes B, Bassett KE. Extracellular matrix involvement in epithelial branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol (N Y 1985) 1986;3:225–260. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5050-7_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Y, Dong Y, Duan Y, Jiang X, Chen C, Deng L. Substrate stiffness influences TGF-β1-induced differentiation of bronchial fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in airway remodeling. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7:419–424. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syedain ZH, Tranquillo RT. TGF-β1 diminishes collagen production during long-term cyclic stretching of engineered connective tissue: implication of decreased ERK signaling. J Biomech. 2011;44:848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arora PD, Narani N, McCulloch CA. The compliance of collagen gels regulates transforming growth factor-beta induction of alpha-smooth muscle actin in fibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:871–882. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65334-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNairn AJ, Brusadelli M, Guasch G. Signaling moderation: TGF-β in exocrine gland development, maintenance, and regulation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowe MJ, Doetschman T, Greenhalgh DG. Delayed wound healing in immunodeficient TGF-beta 1 knockout mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:3–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nandula SR, Amarnath S, Molinolo A, Bandyopadhyay BC, Hall B, Goldsmith CM, et al. Female mice are more susceptible to developing inflammatory disorders due to impaired transforming growth factor beta signaling in salivary glands. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1798–1805. doi: 10.1002/art.22715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall BE, Zheng C, Swaim WD, Cho A, Nagineni CN, Eckhaus MA, et al. Conditional overexpression of TGF-beta1 disrupts mouse salivary gland development and function. Lab Invest. 2010;90:543–555. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ungefroren H, Sebens S, Groth S, Gieseler F, Fändrich F. The Src family kinase inhibitors PP2 and PP1 block TGF-beta1-mediated cellular responses by direct and differential inhibition of type I and type II TGF-beta receptors. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:524–535. doi: 10.2174/156800911795538075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh MF, Ampasala DR, Hatfield J, Vander Heide R, Suer S, Rishi AK, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates intestinal epithelial focal adhesion kinase synthesis via Smad- and p38-dependent mechanisms. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:385–399. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aoyagi-Ikeda K, Maeno T, Matsui H, Ueno M, Hara K, Aoki Y, et al. Notch induces myofibroblast differentiation of alveolar epithelial cells via transforming growth factor-{beta}-Smad3 pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:136–144. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0140oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du J, Wu Y, Ai Z, Shi X, Chen L, Guo Z. Mechanism of SB431542 in inhibiting mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell Signal. 2014;26:2107–2116. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Duyn Graham L, Sweetwyne MT, Pallero MA, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Intracellular calreticulin regulates multiple steps in fibrillar collagen expression, trafficking, and processing into the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7067–7078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wierzbicka-Patynowski I, Mao Y, Schwarzbauer JE. Analysis of fibronectin matrix assembly. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2004;Chapter 10(Unit 10.12) doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1012s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingber DE. Mechanosensation through integrins: cells act locally but think globally. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1472–1474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530201100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barczyk M, Carracedo S, Gullberg D. Integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:269–280. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0834-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meighan CM, Schwarzbauer JE. Temporal and spatial regulation of integrins during development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:520–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz MA. Integrins and extracellular matrix in mechanotransduction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:1–13. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazzoni G, Shih DT, Buck Ca, Hemler ME. Monoclonal antibody 9EG7 defines a novel beta 1 integrin epitope induced by soluble ligand and manganese, but inhibited by calcium. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25570–25577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arahira T, Todo M. Effects of Proliferation and Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Compressive Mechanical Behavior of Collagen/β-TCP Composite Scaffold. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2014;39C:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steward AJ, Thorpe SD, Vinardell T, Buckley CT, Wagner DR, Kelly DJ. Cell-matrix interactions regulate mesenchymal stem cell response to hydrostatic pressure. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:2153–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steward AJ, Wagner DR, Kelly DJ. The pericellular environment regulates cytoskeletal development and the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and determines their response to hydrostatic pressure. Eur Cell Mater. 2013;25:167–178. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v025a12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Izal I, Aranda P, Sanz-Ramos P, Ripalda P, Mora G, Granero-Moltó F, et al. Culture of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on of poly(L-lactic acid) scaffolds: potential application for the tissue engineering of cartilage. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1737–1750. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bian L, Zhai DY, Zhang EC, Mauck RL, Burdick JA. Dynamic compressive loading enhances cartilage matrix synthesis and distribution and suppresses hypertrophy in hMSC-laden hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:715–724. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bian L, Guvendiren M, Mauck RL, Burdick JA. Hydrogels that mimic developmentally relevant matrix and N-cadherin interactions enhance MSC chondrogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013:1214100110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones J. Substrate stiffness regulates extracellular matrix deposition by alveolar epithelial cells. Res Rep Biol. 2011;1 doi: 10.2147/RRB.S13178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harunaga JS, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Local and global dynamics of the basement membrane during branching morphogenesis require protease activity and actomyosin contractility. Dev Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gudjonsson T, Rønnov-Jessen L, Villadsen R, Rank F, Bissell MJ, Petersen OW. Normal and tumor-derived myoepithelial cells differ in their ability to interact with luminal breast epithelial cells for polarity and basement membrane deposition. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:39–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Streuli CH, Bailey N, Bissell MJ. Control of mammary epithelial differentiation: basement membrane induces tissue-specific gene expression in the absence of cell-cell interaction and morphological polarity. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1383–1395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mollard R, Dziadek M. A correlation between epithelial proliferation rates, basement membrane component localization patterns, and morphogenetic potential in the embryonic mouse lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:71–82. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.1.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moore Ka, Polte T, Huang S, Shi B, Alsberg E, Sunday ME, et al. Control of basement membrane remodeling and epithelial branching morphogenesis in embryonic lung by Rho and cytoskeletal tension. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:268–281. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jaskoll T, Melnick M. Submandibular gland morphogenesis: stage-specific expression of TGF-alpha/EGF, IGF, TGF-beta, TNF, and IL-6 signal transduction in normal embryonic mice and the phenotypic effects of TGF-beta2, TGF-beta3, and EGF-r null mutations. Anat Rec. 1999;256:252–268. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19991101)256:3<252::AID-AR5>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts AB, Heine UI, Flanders KC, Sporn MB. Transforming Growth Factor-b. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;580:225–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb17931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silberstein GB. Epithelium-dependent extracellular matrix synthesis in transforming growth factor-beta 1-growth-inhibited mouse mammary gland. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:2209–2219. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou L, Dey CR, Wert SE, Whitsett JA. Arrested lung morphogenesis in transgenic mice bearing an SP-C-TGF-beta 1 chimeric gene. Dev Biol. 1996;175:227–238. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khalil N, Bereznay O, Sporn M, Greenberg AH. Macrophage production of transforming growth factor beta and fibroblast collagen synthesis in chronic pulmonary inflammation. J Exp Med. 1989;170:727–737. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Border WA, Okuda S, Languino LR, Sporn MB, Ruoslahti E. Suppression of experimental glomerulonephritis by antiserum against transforming growth factor beta 1. Nature. 1990;346:371–374. doi: 10.1038/346371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Connor TB, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Danielpour D, Dart LL, Michels RG, et al. Correlation of fibrosis and transforming growth factor-beta type 2 levels in the eye. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1661–1666. doi: 10.1172/JCI114065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu Y-C, Chen M-J, Yu Y-M, Ko S-Y, Chang C-C. Suppression of TGF-β1/SMAD pathway and extracellular matrix production in primary keloid fibroblasts by curcuminoids: its potential therapeutic use in the chemoprevention of keloid. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:717–724. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1075-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olivieri J, Smaldone S, Ramirez F. Fibrillin assemblies: extracellular determinants of tissue formation and fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2010;3:24. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Curran CS, Keely PJ. Breast tumor and stromal cell responses to TGF-β and hypoxia in matrix deposition. Matrix Biol. 2013;32:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Estany S, Vicens-Zygmunt V, Llatjós R, Montes A, Penín R, Escobar I, et al. Lung fibrotic tenascin-C upregulation is associated with other extracellular matrix proteins and induced by TGFβ1. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weng H-L, Ciuclan L, Liu Y, Hamzavi J, Godoy P, Gaitantzi H, et al. Profibrogenic transforming growth factor-beta/activin receptor-like kinase 5 signaling via connective tissue growth factor expression in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2007;46:1257–1270. doi: 10.1002/hep.21806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J. 2004;18:816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolosova I, Nethery D, Kern JA. Role of Smad2/3 and p38 MAP kinase in TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pulmonary epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1248–1254. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamitani S, Yamauchi Y, Kawasaki S, Takami K, Takizawa H, Nagase T, et al. Simultaneous stimulation with TGF-β1 and TNF-α induces epithelial mesenchymal transition in bronchial epithelial cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;155:119–128. doi: 10.1159/000318854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma B, Kang Q, Qin L, Cui L, Pei C. TGF-β2 induces transdifferentiation and fibrosis in human lens epithelial cells via regulating gremlin and CTGF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;447:689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park J, Schwarzbauer JE. Mammary epithelial cell interactions with fibronectin stimulate epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2014;33:1649–1657. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Benzoubir N, Lejamtel C, Battaglia S, Testoni B, Benassi B, Gondeau C, et al. HCV core-mediated activation of latent TGF-β via thrombospondin drives the crosstalk between hepatocytes and stromal environment. J Hepatol. 2013;59:1160–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Silberstein GB, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Daniel CW. Regulation of mammary morphogenesis: evidence for extracellular matrix-mediated inhibition of ductal budding by transforming growth factor-beta 1. Dev Biol. 1992;152:354–362. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Janebodin K, Buranaphatthana W, Ieronimakis N, Hays AL, Reyes M. An in vitro culture system for long-term expansion of epithelial and mesenchymal salivary gland cells: role of TGF-β1 in salivary gland epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:815895. doi: 10.1155/2013/815895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dallas SL, Sivakumar P, Jones CJP, Chen Q, Peters DM, Mosher DF, et al. Fibronectin regulates latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF beta) by controlling matrix assembly of latent TGF beta-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18871–18880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen Q, Sivakumar P, Barley C, Peters DM, Gomes RR, Farach-Carson MC, et al. Potential role for heparan sulfate proteoglycans in regulation of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) by modulating assembly of latent TGF-beta-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26418–26430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang Z, Mu Z, Dabovic B, Jurukovski V, Yu D, Sung J, et al. Absence of integrin-mediated TGFbeta1 activation in vivo recapitulates the phenotype of TGFbeta1-null mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:787–793. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Munger JS, Sheppard D. Cross talk among TGF-β signaling pathways, integrins, and the extracellular matrix. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:1–17. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Horiguchi M, Ota M, Rifkin DB. Matrix control of transforming growth factor-β function. J Biochem. 2012;152:321–329. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roberts AB, McCune BK, Sporn MB. TGF-β: Regulation of extracellular matrix. Kidney Int. 1992;41:557–559. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y, Cox MK, Coricor G, MacDougall M, Serra R. Inactivation of Tgfbr2 in Osterix-Cre expressing dental mesenchyme disrupts molar root formation. Dev Biol. 2013;382:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meyer-ter-Vehn T, Han H, Grehn F, Schlunck G. Extracellular matrix elasticity modulates TGF-β-induced p38 activation and myofibroblast transdifferentiation in human tenon fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:9149–9155. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sieczkiewicz GJ, Herman IM. TGF-β1 signaling controls retinal pericyte contractile protein expression. Microvasc Res. 2003;66:190–196. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(03)00055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shi-wen X, Parapuram SK, Pala D, Chen Y, Carter DE, Eastwood M, et al. Requirement of transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1 for transforming growth factor beta-induced alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and extracellular matrix contraction in fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:234–241. doi: 10.1002/art.24223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Desmoulière a, Geinoz a, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:103–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Menko AS, Kreidberg JA, Ryan TT, Van Bockstaele E, Kukuruzinska MA. Loss of alpha3beta1 integrin function results in an altered differentiation program in the mouse submandibular gland. Dev Dyn. 2001;220:337–349. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lourenço SV, Lima DMC, Uyekita SH, Schultz R, de Brito T. Expression of beta-1 integrin in human developing salivary glands and its parallel relation with maturation markers: in situ hybridisation and immunofluorescence study. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:1064–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Margadant C, Sonnenberg A. Integrin-TGF-beta crosstalk in fibrosis, cancer and wound healing. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:97–105. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tse JR, Engler AJ. Preparation of hydrogel substrates with tunable mechanical properties. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2010;Chapter 10(Unit 10.16) doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1016s47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Inman GJ. SB-431542 Is a Potent and Specific Inhibitor of Transforming Growth Factor-beta Superfamily Type I Activin Receptor-Like Kinase (ALK) Receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:65–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sequeira SJ, Soscia DA, Oztan B, Mosier AP, Jean-Gilles R, Gadre A, et al. The regulation of focal adhesion complex formation and salivary gland epithelial cell organization by nanofibrous PLGA scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3175–3186. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.