Abstract

Background

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) can masquerade as an ovarian epithelial neoplasm, with very similar presenting clinical symptoms and imaging findings. The gold standard in differentiating between these two diagnoses lies in tissue pathology.

Case report

This is a case of MPM that was initially misdiagnosed as ovarian cancer based on family history, imaging, and surgical findings. Tissue diagnosis preoperatively would have changed the planned procedure. Retrospectively, after the diagnosis of MPM, the patient was found to have had an indirect exposure to asbestos through her father.

Conclusions

This case highlights the importance of keeping a broad differential when diagnosing ovarian malignancies, collecting both family and social histories (including screening for exposure to asbestos), and the benefit of obtaining tissue diagnosis when MPM is suspected.

Keywords: Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma, Ovarian neoplasm, Asbestos

Highlights

-

•

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma can masquerade as ovarian epithelial neoplasm.

-

•

Due to similar presenting clinical symptoms, differential diagnosis can be difficult.

-

•

The key to differentiating between these two diagnoses lies in tissue pathology.

-

•

Family, social, and occupational exposure histories are crucial if suspected ovarian malignancy

-

•

Importance of considering broad differential when ovarian malignancy is suspected.

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology

Malignant mesothelioma is an aggressive tumor of serosal surfaces, most commonly involving the pleura followed by the peritoneum (Boffetta, 2007). Incidence rates range between 0.2 and two cases per million in women (Boffetta, 2007), versus approximately 6.8 cases per million of serous primary peritoneal cancer (Goodman and Shvetsov, 2009). Of 3300 new diagnoses of mesothelioma per year in the United States, approximately 10–15% are peritoneal (Goodman and Shvetsov, 2009; Surveillance, Epidemiology, and EndResults (SEER) Program, 2004), with a mean age at diagnosis of 53 (Teta et al., 2008). A study of 10,589 cases of mesothelioma reported to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database between 1973 and 2005 demonstrated that females account for 44% of peritoneal cases compared to 19% of pleural primaries (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and EndResults (SEER) Program, 2, Teta et al., 2008). Ovarian involvement in mesothelioma is rare. In a United Kingdom registry encompassing 24 years of data on mesotheliomas, 0.03% of mesothelioma-related deaths had presented with an ovarian mass (Merino, 2010). Pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas share many risk factors, the most common of which is exposure to asbestos. In a study of 52 women with malignant mesothelioma, indirect asbestos exposure, as measured by husbands and fathers working in asbestos-related industries, led to an increase in relative risk by ten for developing malignant mesothelioma (Vianna and Polan, 1978).

1.2. Clinical presentation and diagnosis

The most common presenting features in patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) are strikingly similar to that of ovarian cancer and include ascites, abdominal distention, abdominal pain, and occasionally bowel obstruction (Sugarbaker et al., 2003). In cases with ovarian involvement, MPM can appear intraoperatively as primary ovarian cancer with intraperitoneal spread (Clement et al., 1996). The key to differentiating the two diagnoses lies in histologic differences in the appearance of papillae and degree of nuclear atypia. Because it is a rare entity among women, the pathologist may not consider the diagnosis or even have experience in identifying characteristic histopathologic features (Baker et al., 2005). However, early distinction between the two etiologies is crucial because treatment protocols vary significantly.

1.3. Prognosis/survival

In the SEER cancer registry, median survival in MPM was shown to be 10 months and the relative 5-year survival rate was 16% (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and EndResults (SEER) Program, 2004). Examination of this database also shows that age, tumor grade, and gender are independent predictors of prognosis in MPM (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and EndResults (SEER) Program, 2, Teta et al., 2008).

2. Case report

This is a 51-year-old asymptomatic, postmenopausal female with a sister diagnosed at age 49 with ovarian cancer (no BRCA testing) found to have a thickened endometrial stripe on transvaginal ultrasound. An endometrial biopsy (EMB) was performed and showed atypical metaplastic epithelium and atypical mesothelial proliferation described as a tubulopapillary proliferation of low columnar cells with stromal hyalinization, and psammomatous calcifications. She was referred to gynecologic oncology. Physical exam was benign, CT scan was unremarkable, and tumor markers including CEA, CA 19-9, and CA-125 were within normal limits. She had a hysteroscopy and D&C notable for atrophic endometrium and endometrial polyps. The patient desired a prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy based on family history. Pre-operative CT scan revealed extensive peritoneal implants, a right adnexal mass, small pelvic ascites, sigmoid mesocolon implants, and subcentimeter right superior diaphragmatic lymph nodes. Tumor markers were repeated and noted to be within normal limits. Given the findings of psamomma bodies on EMB, the patient's strong family history of ovarian cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis on imaging, primary ovarian cancer was suspected. The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, bilateral pelvic lymph node sampling, appendectomy, tumor debulking, cystourethroscopy, and proctoscopy without complication. Intraoperatively, in addition to the distinct masses that had been noted on imaging, miliary disease and exudates were noted diffusely throughout the peritoneum, and small and large bowel mesenteries. The patient was optimally cytoreduced to subcentimeter residual disease.

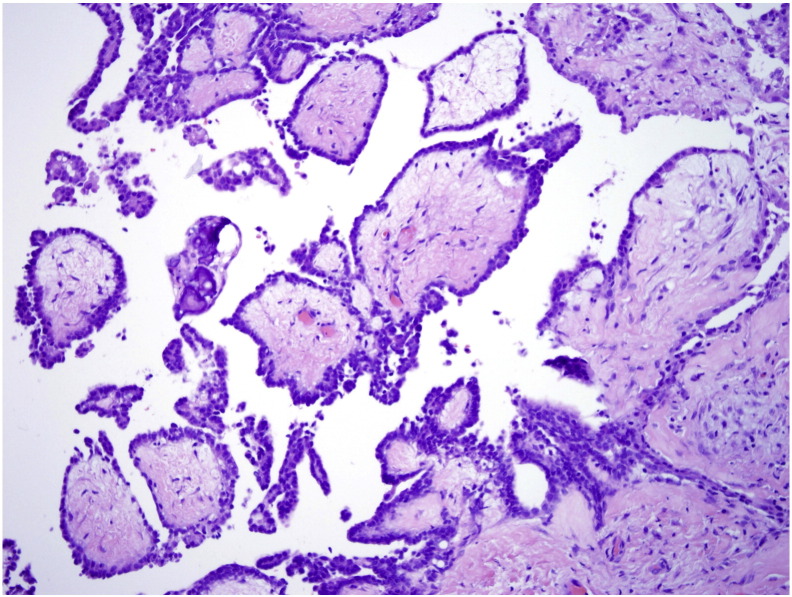

Final pathology revealed MPM. The morphology and immunostaining pattern revealed two distinct growth patterns. The first pattern had distinct papillary architecture (Fig. 1) while the second pattern appeared less well differentiated, consisting of solid sheets of cells (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemistry was performed with strong positivity for mesothelial markers calretinin and CK 5/6. Stains for common adenocarcinoma and epithelial markers including CK7, CK20, ER, D240 and BerEP4 showed patchy positivity and staining for ovarian marker PAX-8 was negative. Overall the two growth patterns showed similar staining patterns, although the solid sheets of cells had a lower percentage of cells staining. The morphology and immunohistochemical staining pattern were most consistent with MPM and therefore was the strongly favored diagnosis by the pathologists.

Fig. 1.

Distinct papillary architecture of MPM, note broad papilla with hyalinized cores.

Fig. 2.

Poorly differentiated pattern with solid sheets of cells.

The patient was referred to medical oncology where she underwent four cycles of cisplatin and pemetrexed. She was then referred by medical oncology to the University of Pittsburgh's Mesothelioma Specialty Care Center where radical tumor cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) with cisplatin was performed. Intraoperatively, multifocal disease was noted on small and large bowel mesenteries, serosal surfaces of the right, transverse, and descending colon, gallbladder, spleen, bilateral hemidiaphragms, as well as adherent disease on the liver surface with invasion into subscapular liver. The surgery was uncomplicated and there was no gross residual disease. Her recovery was unremarkable and three and six month CT scans showed no evidence of disease. However, CT scan ten months later showed disease progression in the peritoneum as well as new ascites. She then completed another four cycles of carboplatin and pemetrexed and video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) pleurodesis for a right-sided pleural effusion. Since that time she has had successive CT scans noting disease progression prompting treatment with gemcitabine, followed by vinorelbine, then doxil. Currently the patient is being treated with carboplatin and pemetrexed.

Retrospectively, with the known diagnosis of MPM, the patient's family history was re-examined for potential risk factors predisposing her to the development of MPM. Her father had been a seaman and developed lung asbestosis and therefore she had household exposure to asbestos through her father.

3. Discussion

MPM is a rare entity that upon initial presentation can be indistinguishable from ovarian cancer. Without a high clinical suspicion among primary care physicians, gynecologists, gynecologic oncologists, and pathologists, misdiagnosis and subsequent mismanagement are likely. Despite the original EMB pathology and history of indirect asbestos exposure, MPM was low on the differential in this case. An ovarian cancer primary was favored given known family history, surgical and CT findings, and overall higher incidence of ovarian malignancies. While histologic diagnosis can be difficult, it would have benefitted this patient if MPM was suspected before surgical treatment was attempted so that HIPEC could have been administered during the patient's initial cytoreductive surgery.

3.1. Histologic distinction

Pre-operative tissue diagnosis can be obtained by CT-guided core needle biopsy or laparoscopic biopsy (van Gelder et al., 1989). Histologic features and immunohistochemical staining characteristics will usually allow the differentiation of MPM from serous and other adenocarcinomas. Specifically, calretinin and CK 5/6 are strongly positive in nearly 100% of MPM, with significantly weaker positive staining to these markers in serous ovarian (Baker et al., 2005). When combined with panels for epithelial and adenocarcinoma (CK7, CK20, ER, D240, BerEP4) and ovarian markers such as PAX-8, the distinction can be made easily. Morphologically, psammoma bodies are more common in ovarian cancer than mesothelioma. However, psammoma bodies were seen in our case of MPM. Examination of papillary architecture, nuclear atypia, and mitotic rates can further aid in distinguishing these two entities. In serous ovarian cancers, the papillae have more hierarchical branching, cellular stratification, and detached cell clusters, whereas in MPM, the papillae are broader with hyalinized cores and no budding. Serous ovarian cancers also have more nuclear atypia with frequent anaplastic or bizarre nuclei and abnormal mitotic figures, as well as higher mitotic rates (Baker et al., 2005).

3.2. Management

Historically MPM patients were treated palliatively with intravenous chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy yielding median survival rates of less than a year. With the advent of complete surgical cytoreduction and HIPEC, survival rates now approach five years (Yan et al., 2009, Alexander et al., 2013). Standard treatment in selected patients, with no evidence of extraperitoneal spread, good performance status, and a disease burden amenable to complete cytoreduction with no deposits over 2 to 2.5 mm (Deraco et al., 2008), includes a combination of cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy (Boffetta, 2007). There are no randomized controlled trials addressing specific protocols, however the two largest multi-center studies utilize cisplatin, mitomycin, or doxorubicin as HIPEC agents (Yan et al., 2009, Alexander et al., 2013). For patients who are not candidates for cytoreductive surgery plus HIPEC, systemic chemotherapy regimens include the antifolate pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin. This protocol is based on studies demonstrating the impact of this drug combination on overall survival rates in pleural mesothelioma (Vogelzang et al., 2003), but studies suggest a similar impact of this protocol on response rate and median survival rate in patients with MPM (Jänne et al., 2005, Carteni et al., 2009). New data investigating gene expression analysis in MPM tumor samples revealed a significant difference in survival based on expression of phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways. MPM patients with overexpression of these pathways had a shorter median survival compared to MPM patients without overexpression (24 months as compared to 69.5 months, P = .035) (Varghese et al., 2011)). The therapeutic value of mTOR inhibitors is currently being evaluated in Phases I and II clinical trials.

4. Conclusions

Age-cohort modeling from SEER estimates that between 2005 and 2050, there will be 6900 cases of MPM diagnosed among women (Moolgavkar et al., 2009). Given the similarities in presentation among patients with MPM and ovarian cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis, many of these cases will likely present to the gynecologist or gynecologic oncologist masquerading as an ovarian malignancy. We're presenting a case of MPM that was initially misdiagnosed as ovarian cancer. This case highlights the value of keeping a broad differential diagnosis, the importance of collecting both family and social histories (including screening for exposure to asbestos), and the benefit of obtaining tissue diagnosis when MPM is suspected.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Macy's Foundation and the Puglisi Gynecologic Oncology Research Fund.

Footnotes

Precis: Report of a case of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma initially misdiagnosed as ovarian cancer, highlighting the importance of keeping a broad differential when diagnosing ovarian malignancies, collecting both family and social histories including screening for exposure to asbestos, and benefit of obtaining tissue diagnosis when MPM is suspected.

References

- Alexander H.R., Jr., Bartlett D.L., Pingpank J.F. Treatment factors associated with long-term survival after cytoreductive surgery and regional chemotherapy for patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Surgery. 2013;153:779. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P.M., Clement P.B., Young R.H. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma in women: a study of 75 cases with emphasis on their morphologic spectrum and differential diagnosis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005;123(5):724–737. doi: 10.1309/2h0n-vrer-pp2l-jdua. (May) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffetta P. Epidemiology of peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Ann. Oncol. 2007;18(6):985–990. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl345. (Jun) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carteni G., Manegold C., Garcia G.M. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma—results from the International Expanded Access Program using pemetrexed alone or in combination with a platinum agent. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:211. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement P.B., Young R.H., Scully R.E. Malignant mesotheliomas presenting as ovarian masses: a report of nine cases, including two primary ovarian mesotheliomas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1996;20:1067–1080. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deraco M., Bartlett D., Kusamura S., Baratti D. Consensus statement on peritoneal mesothelioma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2008;98:268. doi: 10.1002/jso.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M.T., Shvetsov Y.B. Incidence of ovarian, peritoneal, and fallopian tube carcinomas in the United States, 1995–2004. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009;18(1):132–139. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänne P.A., Wozniak A.J., Belani C.P. Open-label study of pemetrexed alone or in combination with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with peritoneal mesothelioma: outcomes of an expanded access program. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2005;7:40. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2005.n.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino M. Malignant mesothelioma mimicking ovarian cancer. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010;18:178S–180S. doi: 10.1177/1066896910370880. (June) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolgavkar S.H., Meza R., Turim J. Pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas in SEER: age effects and temporal trends, 1973–2005. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(6):935–944. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9328-9. (Aug) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarbaker P.H., Welch L.S., Mohamed F., Glehen O. A review of peritoneal mesothelioma at the Washington Cancer Institute. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2003;12:605–621. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(03)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and EndResults (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence—SEER 9 Regs Public-Use, Nov 2003 Sub (1973–2001), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2004.

- Teta M.J., Mink P.J., Lau E. US mesothelioma patterns 1973–2002: indicators of change and insights into background rates. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2008;17:525. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f0c0a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder T., Hoogsteden H.C., Versnel M.A. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a series of 19 cases. Digestion. 1989;43:222. doi: 10.1159/000199880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese S., Chen Z., Bartlett D.L. Activation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathways are associated with shortened survival in patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Cancer. 2011;117:361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vianna N.J., Polan A.K. Non-occupational exposure to asbestos and malignant mesothelioma in females. Lancet. 1978;1(8073):1061–1063. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90911-x. (May 20) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzang N.J., Rusthoven J.J., Symanowski J. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:2636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan T.D., Deraco M., Baratti D. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: multi-institutional experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:6237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]