Abstract

Background

Rapid development and westernisation in Kuwait and other Gulf states have been accompanied by rising rates of obesity, diabetes, asthma, and other chronic conditions. Prenatal experiences and exposures may be important targets for intervention. We undertook a prospective pregnancy–birth cohort study in Kuwait, the TRansgenerational Assessment of Children’s Environmental Risk (TRACER) Study, to examine prenatal risk factors for early childhood obesity. This article describes the methodology and results of follow-up through birth.

Methods

Women were recruited at antenatal clinical visits. Interviewers administered questionnaires during the pregnancy and collected and banked biological samples. Children are being followed up with quarterly maternal interviews, annual anthropometric measurements, and periodic collection of biosamples. Frequencies of birth outcomes (i.e. stillbirth, preterm birth, small and large for gestational age, and macrosomia) were calculated as a function of maternal characteristics and behaviours.

Results

Two thousand four hundred seventy-eight women were enrolled, and 2254 women were followed to delivery. Overall, frequencies of stillbirth (0.6%), preterm birth (9.3%), and small for gestational age (7.4%) were comparable to other developed countries, but not strongly associated with maternal characteristics or behaviours. Macrosomia (6.1%) and large for gestational age (23.0%) were higher than expected and positively associated with pre-pregnancy maternal overweight/obesity.

Conclusions

A large birth cohort has been established in Kuwait. The collected risk factors and banked biosamples will allow examination of the effects of prenatal exposures on the development of chronic disease in children. Initial results suggest that maternal overweight/obesity before pregnancy should be targeted to prevent macrosomia and its associated sequelae of childhood overweight/obesity.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Cohort, Birth outcomes, Obesity, Kuwait

Both developed and developing countries are experiencing a rise in complex chronic non-communicable diseases.1,2 This is particularly evident in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries which have experienced dramatic economic and life style changes over the last few generations, along with a dramatic rise in obesity, diabetes, asthma, neurodevelopmental disorders, and cardiovascular disease.3–5

Lifestyle and personal behaviours have been suggested as important factors in this transition. The diet in these countries has changed from the traditional high-fibre, low-fat Arab diet to a western diet high in unhealthy fast food and sugar-sweetened beverages, with low intake of fruits and vegetables.5,6 The rates of physical inactivity are very high.5,6 Cigarette smoking rates are high among men, although not as frequent among women, but hookah (water pipe) smoking is increasingly common.5,7

Along with this rapid transition in lifestyle and behaviours, there is growing evidence that these chronic diseases have roots early in the developmental process. Adverse health trajectories established in early life may have long-term consequences, a notion grounded in the theory of the early-life origins of chronic disease.8 Characteristics of the in utero environment, independent of genetic susceptibility, influences fetal development that then sets the stage for chronic disease expression across the life course.9–12

The in utero and neonatal developmental periods are important ‘critical windows’ during which the rapidly growing fetus and newborn are particularly susceptible to nutritional, chemical, and psychosocial toxins.13,14 Environmental exposures during these periods may enhance vulnerability to a number of leading maternal and child health problems, including adverse pregnancy outcomes, neurodevelopmental outcomes, allergic sensitisation, respiratory disorders, and obesity and other metabolic disorders.

A number of environmental exposures linked to child health and developmental outcomes15 are prevalent in Kuwait and other GCC countries. These include dietary deficiencies (e.g. vitamin D)16,17 and elevated body burdens of environmental contaminants, such as heavy metals,18 persistent organics,19,20 and pesticides.21–23 In addition, environmental exposures, such as tobacco smoke,24 indoor aeroallergens,25 outdoor air pollution,26 and psychosocial stress,27 are prevalent in Kuwait and have been linked to chronic conditions of adults and children. Other environmental exposures of potential regional concern include chlorination disinfection byproducts (DBPs) and desalination of drinking water.28 All have the potential to influence developmental processes beginning in pregnancy.

Numerous birth cohorts have been established in Europe and North America,29,30 but in Arab countries, despite increasing public health research,31 there are few, if any, such studies. Yet, exposures unique to this region of the world, coupled with the dramatic increase in chronic diseases, make it imperative to evaluate the impact of these environmental factors on this increasingly high-risk population.

The TRansgenerational Assessment of Children’s Environmental Risk (TRACER) Study is a longitudinal Kuwait-based prospective cohort study designed to examine the influence of ongoing environmental exposures (including physical, chemical, and psychosocial factors) on early-life programming of chronic disease risk. The study is a pregnancy–birth cohort with data being gathered prospectively over the course of pregnancy with follow-up of children up to age 3 years. The primary hypothesis is that prenatal exposures to environmental contaminants are associated with increased risk of adiposity of infants at 3 years of age. Secondarily, we hypothesise that pre-natal environmental exposures are associated with early phenotypes of allergy and asthma of infants at 3 years of age. Environmental factors that are prevalent in Kuwait and have been previously implicated in early-life programming of costly chronic diseases in other studies around the world include environmental contaminants, such as methyl mercury, arsenic, and other metals, pesticides, and persistent organics; dietary factors, including vitamin D deficiency; indoor and outdoor air pollution; indoor allergens; and stress.

In this article, we describe the recruitment and follow-up of this pregnancy–birth cohort and present the distribution of maternal characteristics and the prevalence of preterm birth and low and high birthweight in during follow-up between May 2012 and August 2015.

Methods

Recruitment, prenatal evaluation, and follow-up

The TRACER study was open to both Kuwaiti and non-Kuwaiti women attending the primary public health clinics in each of the six Kuwaiti governorates and three additional private clinics/hospitals. In Kuwait, the government provides antenatal health care at primary health care clinics in each governorate. Many Kuwaiti pregnant women elect to receive antenatal health care at public clinics but give birth at private hospitals. Non-Kuwaiti pregnant women tend to utilise the public clinics and hospitals for both antenatal care and delivery. Medical records may be kept by the health care clinic, but are often kept by the patients. Medical records are generally not shared between clinics or between antenatal clinics and delivery hospitals. Therefore, TRACER research assistants were placed in each participating clinic and hospital to collect data from the participants and their medical records.

Permission to recruit participants, to collect data, and to collect biological samples was obtained from the administration and the obstetricians at each health centre. The study was reviewed and monitored by institutional review boards at both the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Dasman Diabetes Institute.

Obstetric clinic staff provided a project brochure to women attending the antenatal clinics and referred interested women to our onsite research assistant. The research assistant explained the study, determined eligibility (pregnant, 18–45 years old, fluent in Arabic or English, and willing to participate), and provided informed consent documents for the pregnant woman and her husband. Upon completion of the informed consent by both the woman and her husband, the woman was enrolled, often at a following clinic visit, and collection of data and biological samples would begin.

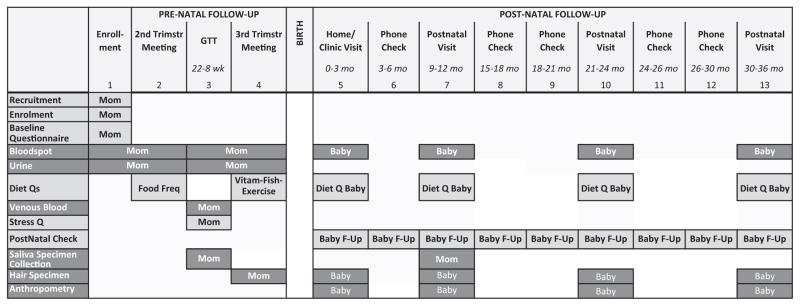

Prenatal risk factors were measured via interviewer-administered questionnaires, and biological samples were collected at the participants’ regular clinical visits (Figure 1). On enrolment, an interviewer administered a questionnaire, which obtained information about demographics, socioeconomic status, family structure, household characteristics, reproductive history, and medical history. Women reported their height and weight before pregnancy. In addition, the mother’s current measured weight with clothes and standing height were extracted from the medical record.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of data collection activities. Baby F-Up is home visit or phone check. During phone checks, the mother is asked about her child’s symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections, diagnosed lower respiratory tract infections (pneumonia and bronchitis), asthma and wheezing, and eczema along with physician visits, hospital stay, and list of medications used for each condition. In addition, we inquired about maternal smoking, the child’s environmental tobacco smoke exposure, maternal stress, the child’s feeding history, and the child’s day care.

Personal smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke during pregnancy were assessed by a questionnaire. The participants were asked ‘Have you ever smoked tobacco products?’ and ‘Do you currently smoke tobacco products’ to define past and current smoking during pregnancy. Women were asked to quantify the number of hours of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke exposure per week at home and outside of home separately for cigarettes and hookah (also known as shisha, narghile, and hubble-bubble). We defined home environmental tobacco smoke as 1 h or more exposure to cigarettes or hookah per week.

At the second follow-up clinical visit (median 29 weeks’ gestation), participants completed a Kuwait-specific food frequency questionnaire (Kuwait FFQ 2009, ©Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation)* and a stress questionnaire that included four global and seven pregnancy perceived stress questions.32,33

During the clinical visit for glucose tolerance testing (22–28 weeks), participants were administered a structured questionnaire on their physical activity. Women were asked if they regularly participated in specific exercises (slow to moderate walking, brisk walking, jogging, running, aerobic exercise, sports, or lifting weights), including frequency and duration per week. They were also asked if they were employed in a physically demanding job and the intensity and duration per week.

At the third follow-up clinical visit (median 33 weeks’ gestation), participants completed a questionnaire on vitamin supplements and Kuwait-specific fish consumption.18

Multiple biological samples were collected during pregnancy and banked for future analyses at the Dasman Diabetes Institute (Figure 1). Blood spots were collected at enrolment and at the third follow-up clinic visits. Venous blood collected during the glucose tolerance test (22–28 weeks) was separated, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C for future analyses. Lead exposure was measured with a spot blood sample (LeadCare® II Blood Lead Test). A maternal hair sample was collected during the third trimester visit.

On the morning of the second and third follow-up visits, participants collected first void urine samples at home which they brought to the clinic. These urine samples were aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

During the clinic visit for glucose tolerance testing, participants were instructed on the collection of repeated saliva samples (upon waking up, 45 min, 4 h, and 10 h after waking up, and before retiring to bed) on two separate days. These samples were stored in the home freezer until picked up by the study staff and then stored at −80°C.

The status of the pregnancy was recorded at each follow-up encounter. Weeks of gestation at each encounter were estimated using the interview date and date of last menstrual cycle. Stillbirth was defined as pregnancy loss after 20 weeks and preterm birth as birth before 37 weeks of gestation.

Postnatal follow-up

Within 3 months following the expected delivery, the mother was called to obtain the baby’s birth date, birthweight and length, and mode of delivery. The mother was asked to recall her last measured weight at the end of her pregnancy and any diagnosis and treatment for gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension.

Babies were excluded from follow-up if a fetal chromosomal abnormality was reported, which may influence outcomes being studied or if the baby required care in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) which included mechanical ventilation or high-level oxygen therapy at the time of birth.

The mother and newborn were visited at home within 3 months of delivery, where blood spot, hair, and anthropometric measures of the child were collected. A repeat maternal saliva sample was collected as described above.

The World Health Organization (WHO) birthweight percentile for gestational week calculator was used to define small for gestational age (below the 10th percentile, SGA) and large for gestational age (above the 90th percentile, LGA). Babies with a birthweight of 4000 g or more were classified as high birthweight (macrosomia).

In continuing follow-up, the mother and newborn are being interviewed periodically (by phone or home visit) quarterly from birth to age 3 years (Figure 1), to ascertain respiratory symptoms (e.g. wheezing, eczema, allergic rhinitis), and the child’s diet (transition from breast milk or formula to solid food). Each postnatal telephone interview includes administration of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to the mother.34

Annual in-person follow-up includes interviews to obtain interval exposure assessments (e.g. parental and child diet and behavioural assessments) and outcomes of interest, as well as anthropometric measurement of the child (Figure 1). Blood spot and hair samples from the child also are collected. During the child’s first annual visit, mothers again provide repeated saliva samples (five over one day) on two separate days. Blood lead of the child (LeadCare® II Blood Lead) is measured at the child’s first and second annual visits.

Statistical analysis

We examined the frequency of maternal characteristics (nationality, age, parity, income, and education), maternal risk factors (pre-pregnancy overweight/ obesity, smoking, environmental tobacco smoke exposure, and physical activity), and the frequency and associations with birth outcomes (preterm birth, SGA, LGA, and macrosomia). Continuous characteristics with symmetric distributions are presented as mean (±SD) and those with non-symmetric distributions are presented as median (lower–upper quartile). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (%). Characteristics are presented overall and by nationality and by birth outcomes and compared using the chi-square test. We further used the Cochran–Armitage test to evaluate trends in ordinal variables. We calculated the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the prevalence of preterm birth: macrosomia, large for gestational age, and small for gestational age. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

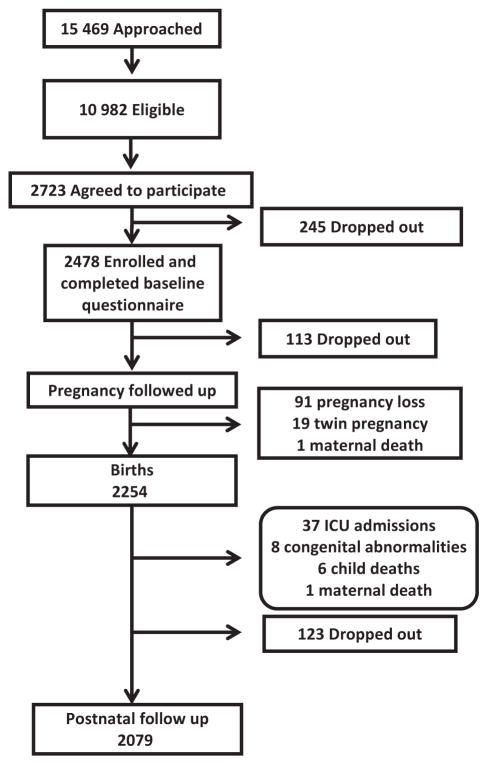

A total of 15 469 women were approached at the maternity clinics between May 2012 and May 2015 (Figure 2) out of whom 10 982 (71%) were eligible. Of these, 2723 (25%) women agreed to participate and 91% of those (2478 women) were enrolled and completed the baseline questionnaire. The women who agreed to participate were similar in age distribution to the ones eligible who did not agree to participate (Table 1); however, they were more likely to be non-Kuwaiti, with a greater proportion recruited at public clinics rather than private clinics (Table 1). In our study, 32% of Kuwaiti women attended public antenatal clinics, but 86% gave birth in private hospitals, while 91% of non-Kuwait women attended public antenatal clinics, but only 9% gave birth in private hospitals.

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing the participation in the TRACER study.

Table 1.

Comparison of pregnant women approached, eligible, and enrolled (% of eligible) into the TRACER study

| Characteristic | Approached | Eligible | Enrolled | (% Eligible) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 15 469 | 10 982 | 2478 | 23 |

| Age group | ||||

| <25 | 3362 | 2414 | 577 | 24 |

| 25–30 | 5281 | 3590 | 930 | 26 |

| 30–35 | 3579 | 2426 | 641 | 26 |

| 35+ | 1827 | 1288 | 314 | 24 |

| Missing | 1420 | 1264 | 16 | 1 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Kuwaiti | 8791 | 5723 | 739 | 13 |

| Non- Kuwaiti | 6573 | 5168 | 1739 | 34 |

| Missing | 105 | 91 | 0 | – |

| Clinic | ||||

| Private | 5045 | 4210 | 585 | 14 |

| Public | 7762 | 6287 | 1740 | 28 |

| Other | 2657 | 485 | 153 | 32 |

| Missing | 5 | 0 | 0 | – |

Most women were enrolled in the second trimester (1112 women, 48%), with 387 women (17%) enrolled in the first trimester and 832 (36%) in the third trimester. In addition, 147 women completed the baseline questionnaire after delivery and had missing gestational age information. There were 2254 (83%) women followed through August 2015. Of the women who dropped out, the most common reasons given were ‘does not wish to participate’ (51%), ‘husband refused’ (17%), and ‘unavailable’ (14%). During this pregnancy follow-up, there were 91 pregnancy losses (miscarriages or stillbirth), 19 twin pregnancies, and one maternal death which excluded participants from further follow-up. Through August 2015, there were 2254 deliveries and birth data were collected on 2245 children. In postnatal follow-up, 37 infants have been dropped for neonatal intensive care unit admissions, eight for congenital abnormalities, six for child deaths, and one for maternal death after birth of the child.

Table 2 presents the numbers of questionnaire and biological samples collected for the participating women during their follow-up visits while pregnant, through birth as of the end of August 2015.

Table 2.

Counts of measures and biological samples at each study encounter

| Prenatal maternal follow-up

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Timing | Count | % |

| Questionnaires | |||

| Baseline questionnaire | Enrolment | 2478 | 100 |

| Food frequency | 2nd trimester | 2161 | 878 |

| Stress questionnaire | 2nd trimester | 2080 | 84 |

| Fish, vitamin, exercise | 3rd trimester | 2121 | 86 |

| Biosamples | |||

| Mother blood spot | 2nd trimester | 1250 | 50 |

| 3rd trimester | 2060 | 83 | |

| Mother venous blood | 24–28 weeks | 1465 | 59 |

| Mother hair | 3rd trimester | 1826 | 74 |

| Mother urine | 2nd trimester | 1222 | 49 |

| 3rd trimester | 1680 | 68 | |

| Mother blood lead | 3rd trimester | 1577 | 64 |

| Mother saliva | 24–28 weeks | 1006 | 41 |

Maternal characteristics

The majority of women enrolled (70%) were non-Kuwaiti (n = 1739), while 30% were Kuwaiti nationals (n = 739). The mean age of the women was 28.4 years (±5.0), and the median parity was 1.0 (interquartile range 0 to 2). The average pre-pregnancy BMI was 26.4 (±5.1) kg/m2. Age at enrolment, active smoking, and home exposure to ETS were similar in Kuwaiti and non-Kuwaiti women (Table 3). However, a higher proportion of Kuwaitis compared with non-Kuwaitis had three or more children, higher monthly income, and education beyond high school.

Table 3.

Maternal baseline characteristics by nationality

| Total

|

Kuwaiti

|

Non-Kuwaiti

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P-value | |

| 2478 | 739 | 1739 | |||||

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||||

| Arab | 2275 | 92 | 679 | 94 | 1596 | 92 | |

| Iranian | 56 | 2 | 45 | 6 | 11 | 1 | |

| Asian | 121 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 121 | 7 | |

| Other | 11 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1 | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <25 | 578 | 24 | 180 | 25 | 398 | 23 | 0.11 |

| 25–30 | 930 | 38 | 261 | 36 | 669 | 39 | |

| 30–35 | 641 | 26 | 178 | 25 | 463 | 27 | |

| 35+ | 315 | 13 | 108 | 15 | 207 | 12 | |

| Parity | |||||||

| 0 | 819 | 34 | 219 | 31 | 600 | 35 | <0.001 |

| 1–2 | 1155 | 48 | 305 | 44 | 850 | 50 | |

| 3 or more | 437 | 18 | 173 | 25 | 264 | 15 | |

| Monthly income in KD | |||||||

| <400 | 676 | 28 | 13 | 2 | 663 | 39 | <0.001 |

| 400–800 | 791 | 33 | 77 | 11 | 714 | 42 | |

| 800–1600 | 547 | 23 | 279 | 41 | 268 | 16 | |

| 1600< | 371 | 16 | 319 | 46 | 52 | 3 | |

| Education | |||||||

| HS or less | 735 | 30 | 144 | 20 | 591 | 34 | <0.001 |

| 2-year diploma | 384 | 16 | 198 | 27 | 186 | 11 | |

| 4-year college+ | 1341 | 55 | 381 | 53 | 960 | 55 | |

| Maternal risk factors | |||||||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI group | |||||||

| Normal or less | 1099 | 45 | 346 | 49 | 753 | 44 | 0.06 |

| Overweight | 802 | 33 | 211 | 30 | 591 | 34 | |

| Obese | 526 | 22 | 153 | 22 | 373 | 22 | |

| Smoking during pregnancy | |||||||

| No | 2375 | 98 | 691 | 98 | 1684 | 98 | 0.90 |

| Yes | 53 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 38 | 2 | |

| Home environmental tobacco smoke | |||||||

| No | 1674 | 70 | 494 | 72 | 1180 | 69 | 0.14 |

| Yes | 717 | 30 | 190 | 28 | 527 | 31 | |

| Physical activity | |||||||

| None | 1562 | 74 | 407 | 71 | 1155 | 75 | 0.056 |

| Mild | 300 | 14 | 86 | 15 | 214 | 14 | |

| Mod/vigorous | 254 | 12 | 84 | 15 | 170 | 11 | |

Overall, more than half of the women were overweight (33%) or obese (22%) before they became pregnant (Table 3). Only 6% (n = 143) of the participants reported smoking before becoming pregnant. Current smoking during this pregnancy was very rare (2%); however, exposure to home ETS was common (30%, Table 3). Only 26% of women reported any type of regular exercise (slow walking or more) and only 12% reported regular exercise as strenuous as brisk walking or vigorous work (Table 3).

Stillbirth and preterm deliveries

Among women recruited before 20 weeks of gestation (n = 1275), the frequency of stillbirth was 0.6% (95% CI 0.2, 0.8). The proportion of women with pre-term deliveries was 9.3% (95% CI 8.1, 10.5). Preterm birth was more frequent among Kuwaiti women (12.6%) compared with non-Kuwaitis (8.0%, Table 4). Preterm births were more frequent among women who were active smokers (19.2%) compared with non-smokers (9.1%, Table 4). There was no difference in preterm delivery by maternal age, parity, weight, physical activity, or home ETS exposure (Table 3).

Table 4.

Proportion of infants with preterm delivery, small for gestational age (SGA), large for gestational age (LGA), and macrosomia by maternal characteristics and risk factors

| Preterm

|

SGA

|

LGA

|

Macrosomia

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | P-value | N | % | P-value | % | P-value | N | % | P-value | |

| Total | 2115 | 9.3 | 2035 | 7.4 | 23.0 | 2140 | 6.1 | ||||

| Nationality | |||||||||||

| Kuwaiti | 597 | 12.6 | 0.001 | 585 | 7.7 | 0.77 | 19.2 | 0.01 | 636 | 3.5 | 0.0008 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 1518 | 8.0 | 1450 | 7.3 | 24.5 | 1504 | 7.3 | ||||

| Age group | |||||||||||

| 18–24 | 486 | 8.6 | 0.82 | 464 | 8.4 | 0.16 | 16.2 | <0.001 | 472 | 5.3 | 0.13 |

| 25–29 | 809 | 9.0 | 787 | 8.4 | 23.0 | 807 | 5.3 | ||||

| 30–34 | 550 | 9.8 | 528 | 5.3 | 25.6 | 538 | 6.1 | ||||

| 35+ | 268 | 10.5 | 256 | 7.0 | 29.7 | 262 | 9.2 | ||||

| Parity | |||||||||||

| 0 | 709 | 8.9 | 0.66 | 685 | 8.2 | 0.36 | 16.6 | <0.001 | 694 | 3.8 | 0.002 |

| 1+ | 1403 | 9.5 | 1349 | 7.0 | 26.2 | 1270 | 7.2 | ||||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI group | |||||||||||

| Underweight | 30 | 10.0 | 0.45 | 31 | 6.5 | 0.18 | 6.5 | <0.0001 | 32 | 0.0 | 0.0002 |

| Normal | 909 | 8.3 | 876 | 8.6 | 18.4 | 893 | 3.7 | ||||

| Overweight | 697 | 10.6 | 671 | 6.9 | 26.4 | 686 | 7.4 | ||||

| Obese | 453 | 9.5 | 434 | 5.3 | 28.1 | 441 | 9.1 | ||||

| Smoking during pregnancy | |||||||||||

| No | 2066 | 9.1 | 0.02 | 1990 | 7.4 | 0.70 | 22.9 | 0.55 | 2022 | 6.1 | 0.63 |

| Yes | 47 | 19.2 | 45 | 8.9 | 26.7 | 46 | 4.4 | ||||

| Home environmental tobacco smoke | |||||||||||

| No | 1477 | 9.3 | 0.86 | 1427 | 7.2 | 0.50 | 22.8 | 0.77 | 1447 | 5.9 | 0.63 |

| Yes | 626 | 9.1 | 599 | 8.0 | 23.4 | 607 | 6.4 | ||||

| Physical activity | |||||||||||

| None | 1452 | 8.8 | 0.47 | 1406 | 7.2 | 0.87 | 22.4 | 0.56 | 1428 | 6.2 | 0.96 |

| Mild | 281 | 6.8 | 273 | 8.1 | 23.8 | 277 | 5.8 | ||||

| Mod/vigorous | 232 | 9.5 | 228 | 7.0 | 25.4 | 233 | 6.0 | ||||

Birthweight

Small for gestational age (SGA) was reported for 7.4% (95% CI 6.4, 8.6) of births. There was no difference in the frequency of SGA among Kuwaiti and non-Kuwaiti mothers, by age, or parity (Table 4). Overweight and obese women had lower frequencies of SGA babies.

Large for their gestational age (LGA) was reported in 23.0% (95% CI 21.1, 24.8) of births and macrosomia in 6.1% (95% CI 5.1, 7.1, Table 4). LGA and macrosomia were more frequent among non-Kuwaitis, mothers who were older, who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy, and for second and later (parity 1+) births (Table 4).

Discussion

The TRACER study successfully recruited a large number of pregnant women into a prospective pregnancy–birth cohort in Kuwait. TRACER is one of the largest pregnancy–birth cohorts in the region and the only one, to our knowledge, in the Arabian Gulf countries. While more Kuwaitis were approached than non-Kuwaitis, we had higher recruitment among non-Kuwaitis leading to a final distribution of nationalities similar to the Kuwaiti general population. Long-term retention until delivery was fairly good among the non-Kuwaitis and Kuwaitis (76% and 89%, respectively). The reasons most commonly stated for dropping from the study were lack of interest, lack of time, or husband refusal. Dropping out of the study is not unexpected as the Kuwait population is not accustomed to prospective research studies. However, the fairly high retention rates suggest that this is changing, and the value of local scientific studies is being appreciated. The value of this study will grow as follow-up of these children continues.

Comparing the frequency of birth outcomes in this sample to regional and international data is useful in understanding the comparability of the TRACER sample to other populations and cohorts. Stillbirth rate was 6 per 1000 births, which is higher than but consistent with the 2009 estimated rate of 5 per 1000 births for Kuwait.35 The 9.3% proportion of preterm birth from our study was slightly lower than the 9.7% among singleton births in the US in 2013.36 The 7.4% proportion of SGA was similar to the 6.3% among singleton births in the US in 2013.36 However, LGA was found in about 23% of infants which is higher than the expected 10% using WHO standards, or rates among whites in the US (11.7%) in the late 1990s.37

We found higher frequencies of preterm birth among Kuwaiti women, and higher frequencies of macrosomia and LGA among non-Kuwaiti women. Kuwaiti women had a higher socioeconomic status and more children than non-Kuwaiti women. The non-Kuwaiti women are predominantly from other Arab and Asian countries. The maternal age distribution was similar for Kuwaiti and non-Kuwaiti women. The frequency of pre-pregnancy obesity was also similar, although non-Kuwaiti women were more frequently overweight or obese than Kuwaiti women. Maternal age, especially being >35 years, was associated with increased adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as macrosomia, which is consistent with the literature.38 We found that pre-pregnancy overweight/ obesity was associated with an increased risk of high birthweight.

The majority of women were recruited in the second trimester (48%) and a significant proportion (35%) in the third. This limits our ability to evaluate pregnancy outcomes, such as miscarriage and stillbirth, which may have occurred before a woman enrolled. For outcomes assessed later in pregnancy or post-delivery, such as preterm birth and birthweight, this is less of a concern. Compared with Kuwaiti women, non-Kuwaitis were less likely to be recruited earlier in the pregnancy, but when we compared some of the baseline characteristics by trimester of recruitment, we did not find any differences. Another concern is the response rate of only 23% overall and only 13% among Kuwaitis. This response rate is lower than other birth cohort studies such as 45% in the Norwegian Mother and Child (MoBa)39 and 64% in the VIVA cohorts.40 The low response rate in our study may affect the external generalisability of our results, but is less likely to affect the internal validity of our future analyses if confounders are adjusted for adequately.

Strengths of the TRACER study include the relatively large sample size for a prospective birth and the unique ability to evaluate environmental health questions and pregnancy, as well as child health outcomes, using urine, blood, saliva, and hair samples collected at multiple time points across pregnancy in the understudied population of the Gulf countries. We have collected detailed information about birthweight and pregnancy conditions within 3 months of delivery. The interviewer-administered questionnaire provides consistency and clarity in the administration and understanding of questions by our participants, unlike self-administered questionnaires. The TRACER design and measurements are consistent with that of many other pregnancy cohorts in the US and European populations. To the extent that common design elements facilitate comparisons across and within these studies, the power to detect environmental risk factors will be significantly improved.

In conclusion, our study provides baseline maternal characteristics for a prospective pregnancy–birth cohort that has the potential for a unique contribution to the environmental risk factors of maternal and child health outcomes. The present findings suggest that LGA and macrosomia are relatively common adverse pregnancy outcomes, with implications for future maternal and child risk of chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The prospective collection of maternal behaviours and biospecimens during pregnancy in this population sample allows TRACER to evaluate environmental factors unique to this region of the world that could be contributing to the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases in Kuwait and other Arab countries. As such, TRACER can fill a major research gap and has the potential to provide needed information about pregnancy and early-life environmental risk factors of chronic diseases.

Acknowledgments

The TRACER study was funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Science. The study is based at and received core support from the Dasman Institute for Diabetes Research in Kuwait. We are particularly grateful for the support and collaboration of the Kuwait Ministry of Health and the administration and clinical staff at the South Hawalli Clinic, Al-Hakim Clinic, West Farwaniya Clinic, Subah Al Naser Clinic, Jahraa Clinic, Al-Sager Clinic, Al-Qurain Health Clinic, New Mowasat Hospital, and Royale Hayat Hospital. Most of all, we thank the mothers and fathers who have given their time to participate in the study, in the hopes of promoting the health of all children in Kuwait.

Footnotes

Provided by Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation through its Population Health Research Institute. Adapted and reproduced with permission of publisher, PHRI. All rights reserved.

References

- 1.Kelishadi R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2007;29:62–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown DW, Mokdad AH, Walke H, As’ad M, Al-Nsour M, Zindah M, et al. Projected burden of chronic, noncommunicable diseases in Jordan. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2009;6:A78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mokdad AH, Jaber S, Aziz MI, AlBuhairan F, AlGhaithi A, AlHamad NM, et al. The state of health in the Arab world, 1990–2010: an analysis of the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. Lancet. 2014;383:309–320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahim HF, Sibai A, Khader Y, Hwalla N, Fadhil I, Alsiyabi H, et al. Non-communicable diseases in the Arab world. Lancet. 2014;383:356–367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehio Sibai A, Nasreddine L, Mokdad AH, Adra N, Tabet M, Hwalla N. Nutrition transition and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Middle East and North Africa countries: reviewing the evidence. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 2010;57:193–203. doi: 10.1159/000321527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akl EA, Gunukula SK, Aleem S, Obeid R, Jaoude PA, Honeine R, et al. The prevalence of waterpipe tobacco smoking among the general and specific populations: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker DJ. The origins of the developmental origins theory. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2007;261:412–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y. A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology: Tracing the Origins of Ill-Health from Early to Adult Life. 2. London: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhlhausler B, Smith SR. Early-life origins of metabolic dysfunction: role of the adipocyte. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;20:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomons NW. Developmental origins of health and disease: concepts, caveats, and consequences for public health nutrition. Nutrition Reviews. 2009;67(Suppl 1):S12–S16. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrijlandt EJ, Gerritsen J. The womb and lung function later in life. European Respiratory Journal. 2004;24:722–723. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:61–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright RJ. Moving towards making social toxins mainstream in children’s environmental health. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2009;21:222–229. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283292629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wigle DT, Arbuckle TE, Walker M, Wade MG, Liu S, Krewski D. Environmental hazards: evidence for effects on child health. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B. 2007;10:3–39. doi: 10.1080/10937400601034563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.el-Sonbaty MR, Abdul-Ghaffar NU. Vitamin D deficiency in veiled Kuwaiti women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1996;50:315–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molla AM, Al Badawi M, Hammoud MS, Shukkur M, Thalib L, Eliwa MS. Vitamin D status of mothers and their neonates in Kuwait. Pediatrics International. 2005;47:649–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2005.02141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans JS, Vorhees DJ, Hussain A, Al-Zenki S, Cooper MA. Fish consumption, mercury intake, and the associated risks to the Kuwaiti population. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal. 2012;18:1014–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo Y, Alomirah H, Cho HS, Minh TB, Mohd MA, Nakata H, et al. Occurrence of phthalate metabolites in human urine from several Asian countries. Environmental Science and Technology. 2011;45:3138–3144. doi: 10.1021/es103879m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z, Alomirah H, Cho HS, Li YF, Liao C, Minh TB, et al. Urinary bisphenol A concentrations and their implications for human exposure in several Asian countries. Environmental Science and Technology. 2011;45:7044–7050. doi: 10.1021/es200976k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeed T, Sawaya WN, Ahmad N, Rajagopal S, Al-Omair A, Al-Awadhi F. Chlorinated pesticide residues in the total diet of Kuwait. Food Control. 2001;12:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saeed T, Sawaya WN, Ahmad N, Rajagopal S, Dashti B, al-Awadhi S. Assessment of the levels of chlorinated pesticides in breast milk in Kuwait. Food Additives and Contaminants. 2000;17:1013–1018. doi: 10.1080/02652030010002081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawaya WN, al-Awadhi FA, Saeed T, Al-Omair A, Ahmad N, Husain A, et al. Dietary intake of organophosphate pesticides in Kuwait. Food Chemistry. 2000;69:331–338. [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Nasser S, El Aziz Fakher O. Kuwait 2009: WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. 2010. Report on results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Mousawi MS, Lovel H, Behbehani N, Arifhodzic N, Woodcock A, Custovic A. Asthma and sensitization in a community with low indoor allergen levels and low pet-keeping frequency. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004;114:1389–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown KW, Bouhamra W, Lamoureux DP, Evans JS, Koutrakis P. Characterization of particulate matter for three sites in Kuwait. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 2008;58:994–1003. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.58.8.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright RJ, Fay ME, Suglia SF, Clark CJ, Evans JS, Dockery DW, et al. War-related stressors are associated with asthma risk among older Kuwaitis following the 1990 Iraqi invasion and occupation. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2009;210(64):630–635. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozisek F. Rolling Revision of the WHO Guielines for Drinking Water Quality by World Health Organization. 2004. Health Risks from Drinking Demineralized Water. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vrijheid M, Casas M, Bergstrom A, Carmichael A, Cordier S, Eggesbo M, et al. European birth cohorts for environmental health research. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120:29–37. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bousquet J, Gern JE, Martinez FD, Anto JM, Johnson CC, Holt PG, et al. Birth cohorts in asthma and allergic diseases: report of a NIAID/NHLBI/MeDALL joint workshop. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014;133:1535–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sweileh WM, Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sawalha AF. Public, environmental, and occupational health research activity in Arab countries: bibliometric, citation, and collaboration analysis. Archives of Public Health. 2015;73:1. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-73-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychology. 1999;18:333–345. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Porto M, Dunkel-Schetter C, Garite TJ. The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: a prospective investigation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;169:858–865. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90016-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, Chou D, Ahmed S, Steinhardt L, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:1319–1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2015;64:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ananth CV, Wen SW. Trends in fetal growth among singleton gestations in the United States and Canada, 1985 through 1998. Seminars in Perinatology. 2002;26:260–267. doi: 10.1053/sper.2002.34772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nybo Andersen AM, Wohlfahrt J, Christens P, Olsen J, Melbye M. Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register linkage study. BMJ. 2000;320:1708–1712. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7251.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K, Nystad W, Skjaerven R, Stoltenberg C. Cohort profile: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:1146–1150. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillman MW, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Lieberman ES, Kleinman KP, Lipshultz SE. Maternal age and other predictors of newborn blood pressure. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;144:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]