Abstract

The amygdala has been shown to be essential for the processing of acute and learned fear across animal species. However, the downstream neural circuits that mediate these fear responses differ depending on the nature of the threat, with separate pathways identified for predator, conspecific, and physically harmful threats. In particular, the dorsomedial part of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VHMdm) is critical for the expression of defensive responses to predator. Here, we tested the hypothesis that this circuit also participates in predator fear memory by transient pharmacogenetic inhibition of VMHdm and its downstream effector, the dorsal periaqueductal grey, during predator fear learning in the mouse. Our data demonstrate that neural activity in VMHdm is required for both the acquisition and recall of predator fear memory, while that of its downstream effector, the dorsal periaqueductal grey, is required only for the acute expression of fear. These findings are consistent with a role for the medial hypothalamus in encoding an internal emotional state of fear.

Keywords: Emotion, VMH, hypothalamic medial zone, DREADD, fear memory

Introduction

Direct exposure of an individual to a threat induces an array of immediate endocrine, autonomic, and behavioral responses aimed at coping with the threat. At the same time, exposure to a threat induces changes in the animal that allow it to adapt to potential future encounters with similar threats. These plasticity mechanisms allow an animal to, for example, avoid locations associated with the threat in order to reduce the possibility of future harm. Both the immediate and long-term consequences of threat exposure depend on the sensory detection and integration of threat-related cues, their processing to produce appropriate physiological and behavioral outputs, and their storage in memory. In addition, in humans we study the emotion of fear that typically accompanies exposure to threats and threat-related cues. Although it remains a matter of debate whether a similar emotional state accompanies threat exposure in other animals (Panksepp, 1989; LeDoux, 2012; Anderson and Adolphs, 2014), researchers routinely use the term “fear” to refer to the autonomic, endocrine and behavioral responses elicited by threats and their cues.

The brain mechanisms underlying fear responses have been widely investigated in rodents using foot shock-based paradigms. In particular, the lateral, basolateral, and central nuclei of the amygdala have been shown to encode and support the cue-dependent acquisition and recall of fear memory (Walker and Davis, 2002; Ehrlich et al., 2009; Gozzi et al., 2010; Haubensak et al., 2010; Wolff et al., 2014). However, several of these amygdala nuclei do not participate in the processing of fear of other threats such as predators or aggressive members of the same species (Kemble et al., 1990; Martinez et al., 2011; Gross and Canteras, 2012). Instead, these depend on an overlapping set of amygdala nuclei (Kemble et al., 1990; Martinez et al., 2011) and independent circuits within the medial hypothalamus (Canteras, 2002; Blanchard et al., 2005; Motta et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2013), a region not recruited during exposure to foot-shock (Canteras, 2002; Blanchard et al., 2005; Motta et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2013). For example, the dorsomedial part of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMHdm), selectively mediates acute predator fear behavior in mice (Martinez et al., 2008; Silva et al., 2013, Kunwar et al., 2015). However, it is less clear whether the medial hypothalamus is also involved in the encoding and recall of predator fear memory. Exposure of rats to a chamber where they previously encountered a cat elicits cFos expression in the dorsal premamillary nucleus (PMD; Canteras et al., 2008), a caudal nucleus of the medial hypothalamus (Canteras and Swanson, 1992), and post-training lesions of PMD suppress the fear responses seen under these circumstances (Cezario et al., 2008) suggesting a role in predator memory recall. More importantly, it remains unclear whether neural activity in the medial hypothalamus is sufficient for the encoding of fear. Stimulation of VMHdm is sufficient to elicit flight behavior across many species, incluing rodents, cats, and monkeys (Hess & Bruegger, 1943; Brown et al., 1969; Lipp and Hunsperger, 1978; Lin et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015; Kunwar et al., 2015) and panic attack in humans (Wilent et al., 2010) and pharmacological activation of PMD or optogenetic activation of VMHdm is sufficient to serve as an unconditioned stimulus for contextual fear conditioning (Pavesi et al., 2011; Kunwar et al., 2015). However, these responses might simply reflect an acute activation of the motor circuits associated with predator fear and leave it unclear whether neural activity in the medial hypothalamus might encode an internal emotional state (Adolphs & Anderson, 2014) independent of its behavioral outputs.

Materials & Methods

Animals

All mice were derived from local EMBL breeding colonies. Transgenic animals carried a bacterial artificial chromosome (clone RP23 225F7) in which a HA-hM4D-2A-TomatoF cassette was inserted at the translational start site of the Nr5a1 gene (Silva et al., 2013) and were backcrossed at least five generations on C57BL/6N (available from EMMA, stock # EM08358). Control animals were non-transgenic littermates. For all other experiments subjects were adult C57BL/6N mice. Animals infected with AAV-Syn::Venus-2A-hM4D in the dorsal PAG were previously described (Silva et al. 2013). Predators were adult male SHR/NHsd rats (Harlan, Correzzana, Italy). All animals were housed at 22–25 C on a 12 hour light-dark cycle with water and food ad libitum. Males were used for all experiments except for data in Figure 1B–G where both males and females were tested. No significant sex difference in behavioral responses was observed. All animals were handled according to protocols approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (#231/2011-B, #121/2011-A).

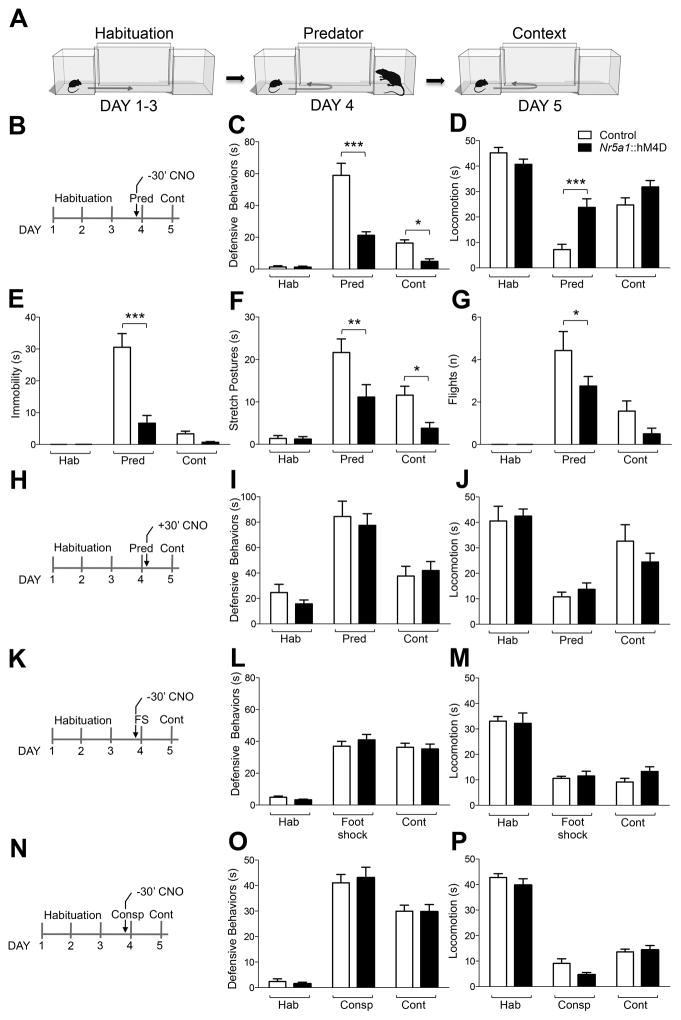

Figure 1. VMHdm is necessary for encoding predator fear memory.

(A) The behavioral testing apparatus consisted of two chambers connected by a narrow corridor. An experimental mouse was continuously housed in one chamber (Home) and allowed to freely explore the corridor and second chamber (Stimulus) once daily for 15 minutes. At the end of the free exploration period on the fourth day, the door to the stimulus chamber was briefly closed to confine the mouse which was then exposed to a predatory rat after which the door was reopened and free exploration continued for an additional 10 minutes. On the fifth day the animal was free to explore the apparatus for 20 minutes and defensive behaviors were quantified as a measure of predator fear memory. (B) The otherwise biologically inert hM4D agonist CNO was administered (3 mg/kg, i.p) 30 minutes before exposure to the predator in Nr5a1::hM4D-2A-tomatoF transgenic and non-transgenic littermates. Nr5a1::hM4D-2A-tomatoF transgenic animals compared to non-transgenic littermates showed a decrease in time spent performing (C) cumulative defensive responses (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,26] = 15.29, P = <0.0001), (E) immobility (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,26] = 21.72, P < 0.0001), (F) stretch postures (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,26] = 2.72, P = 0.084), and (G) number of flights (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,26] = 2.41, P = 0.11), and an increase in (D) locomotion (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,26] = 9.96, P = 0,0006) in the free exploration period immediately after predator exposure (Pred) and when exposed to the predator context (Cont, N = 7–8). (H) When CNO was administered 30 minutes after predator exposure no significant differences between transgenic and non-transgenic littermates were observed 24 hours later in (i) defensive behaviors (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,46] = 0.10, P = 0.91), or (J) locomotion (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,46] = 1.02, P = 0,37), indicating that CNO did not have a persistent effect on behavior (N = 10–18). When the CNO was administered 30 minutes before exposure to an (K) electrical foot shock (Foot shock, 4 × 0.5 s, 0.5 mA, N = 6–8) or (N) aggressive conspecific (N = 7–8), no difference between transgenic and wild-type littermates was observed in (L, O) defensive behaviors (ANOVA, day x treatment: foot shock – F[2,24] = 0.72, P = 0.5, aggressive conspecific – F[2,26] = 0.18, P = 0.83), or (M, P) locomotion (ANOVA, day x treatment: foot shock – F[2,24] = 0.78, P = 0.47, aggressive conspecific – F[2,26] = 1.79, P = 0.19), indicating that CNO did not induce a non-specific impairment of memory (* P< 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001).

Behavioral testing

Behavioral testing was performed as previously described (Silva et al. 2013). Briefly, the experimental apparatus was made of clear Plexiglas and composed of similar detachable home and stimulus chambers that were connected by an opening to a narrow corridor. Both openings could be closed by a manual sliding door. The experimental subject was continuously housed in the home chamber with access to food and water for the entire test. Each day the home cage was carried from the housing room to the testing room and attached to the apparatus and the sliding door opened to give the mouse access to the entire apparatus for 20 minutes (habituation period). In case of foot shock, a metal grid connected to a scrambled electric shock generator (Med Associates, Berlin, VT) was placed into the stimulus compartment. On day 4, following 10 minutes of exploration, the experimental mouse was confined to the stimulus compartment by closing the door and a rat was placed into the stimulus compartment and allowed to interact before the door was re-opened to allow the experimental mouse to escape. In case of foot shock, a scrambled electric current was delivered to the grid over a period of one minute (0.5 mA every 15 s) before the door was re-opened. To prevent injury to the experimental mouse the experimenter held the rat during the direct encounter. On day 5 the experimental mouse was given access to the entire apparatus as on the habituation days. Between each subject the apparatus was cleaned first with 50% ethanol and then detergent and the bedding was changed. The apparatus was washed in an automatic cage washer between testing days to eliminate odors. All testing was performed during the dark phase under red light illumination (40 W). Defensive behaviors were scored during the first 3 minutes of free exploration each day and during the first 3 minutes of the post-stimulus period. Clozapine-N-oxide (3mg/kg i.p. in 0.9% saline; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY or Sigma C0832) or vehicle was injected 30 minutes before the beginning of the test except in Figure 1H were it was injected 30 minutes after exposure to the predator. Animals were naïve to the testing apparatus. Behavior was scored from videotape using Observer software (Noldus, Wageningen, Netherlands) by an experimenter blind to genotype and treatment. Behaviors were scored as follows – immobility: subject motionless, stretch postures: body stretched forward without movement or animal moving slowly towards stimulus compartment in an elongated posture, flight: subject quickly running toward home cage, locomotion: ambulatory movement not characterized by stretch posture. Defensive behavior was the sum of stretch postures, immobility and flight.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with PRISM software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). All data are reported as mean ± standard error measurement. Statistical significance was determined by repeated measures ANOVA with behavior during habituation, stimulus, and context considered as repeated measures coupled to Bonferroni post hoc analysis in case of significance, except in Fig. 2B where it was determined by one way ANOVA coupled to Bonferroni post hoc.

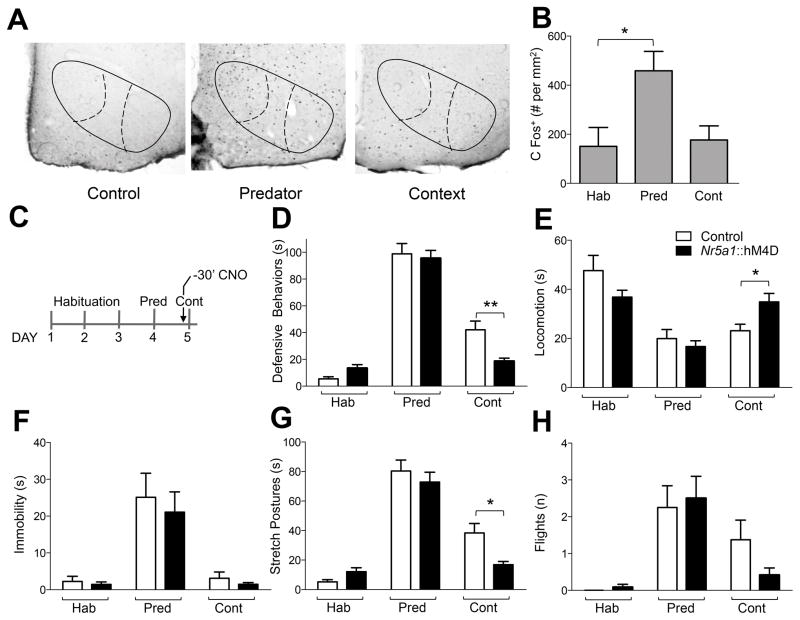

Figure 2. Inhibition of VMHdm impairs fear memory recall.

Quantification of (A) cFos immunohistochemistry in brain sections from mice exposed to a safe environment, a predator and the predatory context in the two-chambered apparatus revealed (B) neural activation in VMHdm only upon a direct exposure to the predator (ANOVA: F[2,10] = 5.22, P = 0.03, N = 4–5). (c) Administration of CNO 30 minutes before exposure to predator context induced a significant decrease in time spent performing (D) defensive responses (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 5.61, P = 0.0061) and (G) stretch postures (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 3.71, P = 0,031), and induced a significant increase of (E) locomotion (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 10.69, P = 0.0001) in Nr5a1::hM4D-2A-tomatoF transgenic mice compared to non-transgenic littermates. Administration of CNO did not cause a significant decrease in (F) immobility (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 0.72, P = 0.49) or (H) flight (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 0.88, P = 0.43), in Nr5a1::hM4D-2A-tomatoF transgenic mice compared to non-transgenic littermates (N = 12–17; * P< 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001).

Histology

For cFos immunochemistry, the experimental mouse was deeply anesthetized with Avertin (375 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 90 minutes after exposure to the stimulus (safe, predator, or context), perfused trans-cardially (4.0% paraformaldehyde, 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) and the brain removed, postfixed (4% PFA overnight), and cryoprotected (20% sucrose, PBS, 4 C, overnight). The brains were frozen and 40 μm coronal sections were cut with a sliding cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and processed for immunohistochemistry with rabbit anti-cFos antiserum (1:20,000, Ab-5, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). The primary antiserum was localized using a variation of the avidin-biotin complex system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, Hsu and Raine, 1981). In brief, sections were incubated for 90 min at room temperature in a solution of biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories) and then placed in the mixed avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase complex solution (ABC Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories) for the same period of time. The peroxidase complex was visualized by a 5 min exposure to chromogen solution (0.05 % 3,30-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride, 0.4 mg/ml nickel ammonium sulfate, 6 μg/ml glucose oxidase, 0.4 mg/ml ammonium chloride in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) followed by incubation in the same solution with 2 mg/ml glucose to produce a blue-black product. The reaction was stopped by extensive washing in PBS. Sections were dehydrated and cover-slipped with quick mounting medium (Eukitt, Fluka Analytical, St. Louis, MO). After staining images were acquired with a microdissector microscope (Leica). The exact position of the brain nucleus of interest was determined by overlaying a reference atlas grid (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001) using white matter landmarks onto the bright field image. The number of cFos positive cells was manually counted (ImageJ Software) by an experimenter who was blind to treatment and normalized over the total area of the nucleus as determined from the atlas overlay.

Viral production

Production and purification of recombinant AAV-Syn::Venus-P2A-HA-hM4D (chimeric capsid serotype 1/2) were as described (Pilpel et al., 2009). Viral titers (>1010 genomic copies per μl) were determined with QuickTiter AAV Quantitation Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) and RT-PCR as previously described (Knobloch et al., 2012).

Stereotaxic injections

Bilateral injections of AAV (100 nl each side) aimed at the dorsal PAG. (Posterior: −3.8 mm, depth: −2.3 mm, lateral: ±1.0 mm; angle 26 degrees, coordinates empirically adapted from Paxinos & Franklin, 2001) were performed using a glass pipette (intraMARK, 10–20 μm tip diameter, Blaubrand, Wertheim, Germany) connected to a syringe and a stereotaxic micromanipulator (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) in deeply anaesthetized animals (Ketavet, Ketamine 100 mg/kg, Xylazine 10 mg/kg, Intervet, Segrate, Italy). Behavioral experiments were performed 2 weeks after surgery.

Results

VMHdm is required for the acquisition of predator fear memory

In order to investigate the role of VMHdm in predator fear memory we used mice expressing the hM4D pharmacogenetic neural inhibition tool (Armbruster et al., 2007) selectively in the central and dorsomedial VMH. Stable expression of hM4D in VMHdm neurons was achieved by constructing transgenic mice in which hM4D was driven by the Nr5a1 gene promoter (Nr5a1:: hM4D-2A-tomatoF). In the brain, expression of hM4D was found restricted to Nr5a1 expressing cells in the VMHdm (Figure S1, Silva et al., 2013; note that we use the term VMHdm to refer to both the central and dorsomedial divisions of this nucleus). Systemic treatment of these mice with clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) causes a rapid suppression of neural activity that persists for several hours (Alexander et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2013). Transgenic and non-transgenic littermates were individually tested in a predator fear apparatus consisting of two clear plexiglass chambers separated by a corridor (Silva et al., 2013; Figure 1A). The mouse was habituated to the home chamber for four days and each day allowed to explore the corridor and second chamber for 10 minutes by the opening of a small door. At the conclusion of the exploratory session on the fourth day, a rat was placed into the second chamber and defensive behaviors (flight, freezing, stretched postures, locomotion) of the mouse were scored for an additional 3 minutes as a measure of acute fear. On the following day the mouse was again allowed to explore the corridor and second chamber where it had encountered the predator and defensive behaviors were scored for 3 minutes as a measure of fear memory (Figure 1A; Silva et al., 2013). The corridor and second chamber were extensively cleaned each day to eliminate the carry-over of olfactory cues. Transgenic mice treated with CNO (3 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes before the encounter with the predator (Figure 1B) displayed significantly reduced defensive behaviors (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,26] = 15.29, P = <0.0001; Figure 1C; Silva et al., 2013) including immobility (Figure 1E), stretch postures (Figure 1F) and flights (Figure 1G), and increased locomotion (Figure 1D) when compared to non-transgenic control animals as previously reported (Silva et al. 2013). On the following day the same animals were re-exposed to the predatory context and their defensive behavior assessed in the absence of VMHdm inhibition. Transgenic animals that had been treated with CNO before the predator exposure showed significantly decreased fear responses to the predator-associated context compared to non-transgenic controls, indicating that VMH activation is required for fear memory acquisition (cumulative defensive responses: ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,26] = 15.29, P = <0.0001; Figure 1C, stretch postures: ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,26] = 2.72, P = 0.084, Figure 1F). Importantly, vehicle-injected Nr5a1:: hM4D transgenic animals did not show differences in defensive behaviors (ANOVA, day x treatment F [6, 34] = 6.36, P = <0.0001, Figure S2A), or locomotion (ANOVA, day x treatment F [6, 34] = 4.70, P = 0.0014, Figure S2B) when compared to vehicle- or CNO-injected non-transgenic littermates (Figure S2). On the other hand, transgenic animals injected with CNO (3 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes after the encounter with the predator did not display any alterations in defensive behavior compared to non-transgenic controls when re-exposed to the predator context on the following day. This finding demonstrates that treatment with CNO on the day of predator exposure does not have a long-lasting effect on defensive behavior 24 hours later (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,46] = 0.10, P = 0.91; Figure 1H–J) and is consistent with the known half-life of CNO in mice (~2 hours; Alexander et al., 2009).

In order to control for a possible non-specific effect of CNO-dependent activation of hM4D on fear memory we treated a group of mice with CNO (3 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes prior to exposure to either foot-shock or an aggressive conspecific to provoke defensive responses that do not depend on VMHdm (Silva et al., 2013; Figure 1K, N). CNO-treated transgenic mice showed no alterations in defensive behavior compared to non-transgenic controls when re-exposed to the threat context 24 hours later (ANOVA, day x treatment: foot shock – F[2,24] = 0.72, P = 0.5; aggressive conspecific – F[2,26] = 0.18, P = 0,83; Figure 1L,M, O, P) arguing against a non-specific effect of hM4D activation on fear memory. Taken together, these findings indicate that neural activity in the VMHdm is required for both the acquisition and encoding of predator fear memory.

VMHdm is required for the expression of predator fear memory

cFos mapping studies in rats reported robust activation of VMHdm following acute exposure to a cat, but not following re-exposure to the chamber where the cat was encountered (Cezario et al., 2008) suggesting that VMHdm is not functionally involved in predator fear memory recall. Initially, we repeated the cFos mapping study in our mouse/rat predator behavioral test to make sure that the absence of cFos activation to predator in VMHdm was not specific to the rat/cat predator pair used in previous studies. Consistent with previous reports no significant increase in cFos immunoreactivity was detected in VMHdm following re-exposure to the chamber where the rat was encountered in our test, despite robust cFos activation following acute rat exposure (Martinez et al., 2008; Silva et al., 2013; ANOVA: F[2,10] = 5.22, P = 0.03; Figure 2AB). To test whether VMHdm was nevertheless functionally involved in predator fear recall we treated a group of mice previously exposed to a rat with CNO (3 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes prior to re-exposure to the chamber where they experienced the rat (Figure 2C). Transgenic mice treated with CNO showed a significant decrease of defensive behavior when compared to non-transgenic controls (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 5.61, P = 0,0061; Figure 2D). Although inhibition of VMHdm did not cause a significant decrease in immobility (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 0.72, P = 0.49; Figure 2F) or flight (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 0.88, P = 0,43; Figure 2H), it did cause a significant decrease in stretch approach (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 3.71, P = 0.03; Figure 2G) and increase in locomotion (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,54] = 10.69, P = 0.0001; Figure 2E) potentially as a result of the low baseline levels of defensive behaviors typically seen during predator fear recall. These results demonstrate that VMHdm is necessary for the expression of fear memory despite an absence of cFos activation.

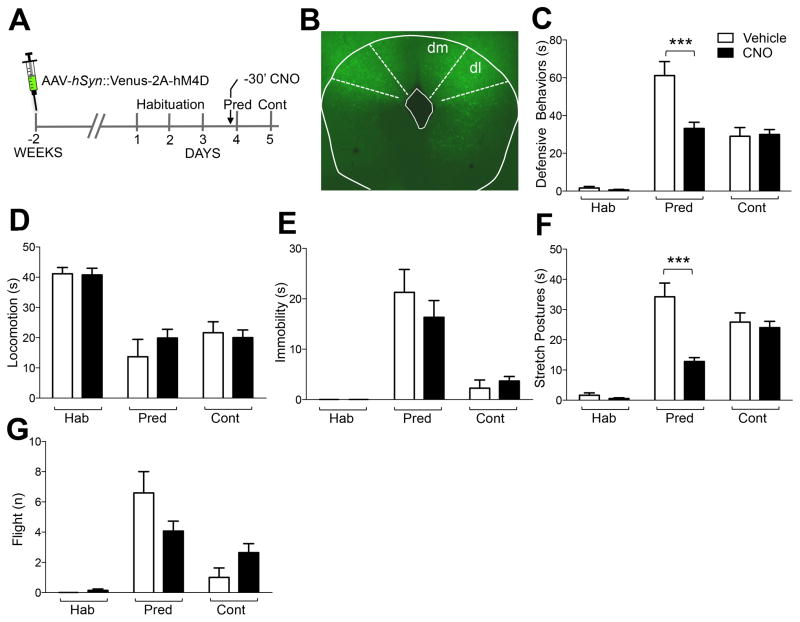

dPAG is not required for the acquisition of predator fear memory

The dorsal periaqueductal grey (dPAG), a brainstem structure involved in the expression of defensive behaviors (Swanson, 2000; Vianna and Brandão, 2003; Kincheski et al., 2012), is the major effector of the medial hypothalamic defensive system (Canteras, 2002) from which it receives extensive monosynaptic afferents (Canteras et al., 1994). We have previously shown that pharmacogenetic inhibition of dPAG suppressed acute defensive responses to predator or social, but not foot shock threat (Silva et al., 2013) consistent with earlier studies in which lesions blocked acute defensive responses to predator (Dielenberg et al., 2004; Aguiar and Guimarães, 2009). However, it is not known whether dPAG is important for the acquisition of predator fear memory. Two weeks following viral delivery of hM4D (AAV-hSyn::Venus-2A-hM4D) into the dPAG (Figure 3AB) mice were subjected to the predator fear test. Treatment with CNO (3 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes prior to rat exposure, caused a significant decrease in defensive behavior when compared to vehicle-treated control mice, as previously reported (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,32] = 12.36, P = 0,0001; Figure 3C–G; Silva et al., 2013). However, when re-exposed to the predator context one day later, CNO-treated mice showed no deficit in defensive behaviors when compared to vehicle-treated control animals (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,32] = 12.36, P = 0,0001; Figure 3C–G). This result demonstrates that neural activity in dPAG is required for the acute expression of defensive responses to predator, but not for the acquisition of predator fear memory. Together with our findings from neural inhibition of VMHdm, these data suggest that neural activity in the medial hypothalamus is sufficient for predator fear memory acquisition.

Figure 3. Inhibition of dPAG impairs acute predator fear but not predator fear memory.

(A) Mice locally infected with AAV-Syn::Venus-2A-hM4D (bilateral injection: 100 nl) in (B) dPAG displayed a significant decrease of (C) defensive responses (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,32] = 12,36, P = 0,0001), and (F) stretch postures (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,32] = 21.24, P = <0,0001), elicited by predator exposure (Pred), but not to the predatory context (Cont) following administration of CNO (3 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes before exposure when compared to similarly infected, vehicle-treated mice. CNO-treated animals showed a non-significant increase in (D) locomotion (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,32] = 1.92, P = 0,16), and decrease in (E) immobility (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,32] = 0.88, P = 0.42), and (G) flight (ANOVA, day x treatment: F[2,32] = 3.89, P = 0,03), when compared to similarly infected, vehicle-treated mice (N = 5–13, *** P < 0.001).

Discussion

It has been proposed that instinctive behaviors elicited in response to environmental stimuli depend on the processing and integration of sensory inputs, the activation of downstream brain structures that encode an internal motivational or emotional state, and the subsequent activation of motor centers that produce the behavioral response (Swanson, 2000; Anderson and Adolphs, 2014). However, the precise location and neural substrates of the encoding of such internal states are poorly described. Several requirements for the encoding of an internal emotional state have been proposed (Anderson and Adolphs, 2014). First, neural activity in the structure should be necessary and sufficient to elicit the behavior. Second, neural activity in the structure should be capable of being elicited by a conditioned stimulus, and thus not be strictly dependent on any particular sensory input (“sensory generalization” or “sensory degeneracy,” Adolphs & Anderson, 2014). Third, neural activity in the structure should be necessary and sufficient for the formation of a memory of the experience. Fourth, the pattern of neural activity in the structure should reflect the tendency of the animal to perform a group of adaptive behaviors, rather than directly correlate with any one behavior (“pleiotropy”, Adolphs & Anderson, 2014). Here, we used the predator fear behavior pathway to test several of these predictions.

We chose the VMHdm for our studies because it is an evolutionary conserved brain structure (Kurrasch et al., 2007) that receives monosynaptic inputs from predator-responsive regions of the medial amygdala (MeA; Choi et al., 2005; Bergan et al., 2014 Kumwar et al., 2015) and provides monosynaptic outputs to the dorsal periaqueductal grey (dPAG), a brainstem structure required for defensive responses to predator (Dielenberg et al., 2004; Aguiar and Guimarães, 2009). Previous work has demonstrated that electrical stimulation of VMHdm elicits panic-attacks in humans (Wilent et al., 2010) and escape behavior in non-human primates (Lipp and Hunsperger, 1978) arguing for a critical role in the production of emotional responses. Pharmacogenetic inhibition of VMHdm in mice suppresses predator fear behavior (Silva et al. 2013) and optogenetic stimulation elicits flight, immobility and avoidance (Lin et al., 2011; Falkner et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2015; Kunwar et al., 2015). These findings argue that VMHdm is a critical node in the instinctive threat response pathway across species.

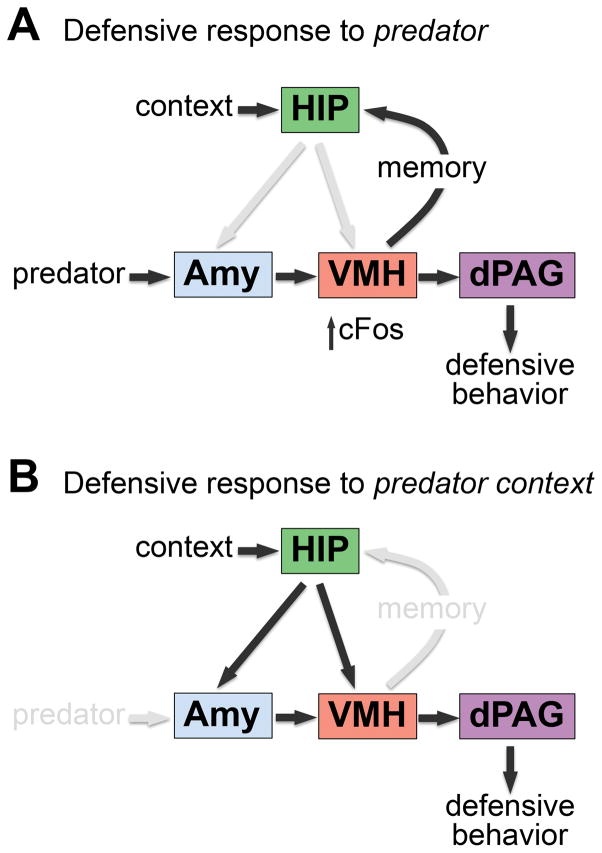

Here we tested the hypothesis that neural activity in VMHdm encodes an internal state of predator fear that can be activated by diverse sensory modalities and that can motivate both immediate and future defensive behavior. Our data demonstrate that VMH is necessary for full defensive responses regardless whether these are induced by predator stimuli (Figure 1C–G) or by a context associated with the predator (Figure 2D–H). These findings suggest that VMH occupies a position in the circuit that is downstream of multiple sensory inputs and is not exclusively part of any one sensory modality (“sensory generalization,” Adolphs & Anderson, 2014). Thus, although VMH receives prominent inputs from MeA that are known to convey olfactory and vomeronasal information about predator (Choi et al., 2005; Papes et al., 2010; Bergan et al., 2014), it can also be activated by non-olfactory predator-associated contextual cues. Contextual conditioning to predator is known to be hippocampus-dependent (Pentkowski et al., 2006) and information about context has been proposed to pass to the medial hypothalamus via hippocampal projections to septum and anterior hypothalamus (Figure 4A,B; Risold and Swanson, 1997; Gross and Canteras, 2012). Importantly, our findings are similar to those found with lesions of the more caudally located PMD (Cezario et al., 2008) and are consistent with the medial hypothalamus encoding a general internal motivational state rather than being a part of one particular sensory pathway. Nevertheless, there may be a preference for the medial hypothalamus to process olfactory and vomeronasal cues as defensive responses to a neutral odor that has been previously associated with foot shock are reduced by PMD lesions (Canteras et al., 2008). We speculate that this reflects an ancestral function of the medial hypothalamus in processing chemosensory information that signal threats and opportunities in the environment.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the putative medial hypothalamus-brainstem predator fear circuit. (A) The VMHdm occupies an intermediate position between predator-derived sensory inputs (amygdala) and motor outputs (dPAG). VMHdm activation instructs both acute fear responses and encoding of fear memory upon exposure to predators. (B) VMHdm mediates defensive responses to a context previously associated with predator exposure via its projections to the dPAG. Contextual cues may be conveyed to the VMHdm through the hippocampus and the amygdala.

Our observation that VMH was required for full defensive responses to predator context (Figure 2D–H), but did not show cFos activation under these circumstances (Figure 2A,B) could reflect the observation that cFos activation requires relatively intense neuronal firing activity (Douglas et al., 1988; Dragunow and Faull, 1989; Lin et al., 2011) and contextual recall may involve lower level of neural activity. Alternatively, this may be due to “homotypic habituation” of c-Fos signaling as a consequence of repeated context exposure leading to lack of a novelty component that has been hypothetized to be necessary for c-Fos induction (Melia et al., 1994). A third possibility is that the mode of activation to acute predator exposure or context exposure could have been different. Because immediate early gene induction typically requires calcium-dependent activation of nuclear signaling pathways (Finkbeiner & Greenberg, 1998) acute predator exposure might be accompanied by the opening of calcium channels such as NMDA receptors, while context might not. We speculate that the resulting signaling could be important for triggering plasticity in VMH required for adjusting its response to future stimuli.

On the other hand, our findings that pharmacogenetic inhibition of dPAG blocked acute defensive responses to predator, but left contextual responses intact (Figure 3C–G) point to distinct functions in predator defense for VMH and dPAG. Notably, under conditions where dPAG is inhibited and defensive behaviors are suppressed, predator fear memory can be acquired, suggesting that the VMH can act independently of its behavioral output. Previous studies have shown that pharmacological activation of PMD or optogenetic activation of VMHdm was able to serve as an unconditioned stimulus during contextual fear conditioning (Pavesi et al., 2011, Kumwar et al., 2015). However, these studies were not able to rule out that this function depended on the activation of downstream motor areas.

The direction of causality between emotional behaviors and internal states has been debated (Anderson and Adolphs, 2014) with William James notably reasoning that emotional behaviors generate emotional states and not vice-versa (James, 1884). Our findings show that an internal state of fear can exist in the absence of its behavioral expression. However, our data seem to contradict earlier studies that found activation of dPAG to serve as an unconditioned stimulus during fear conditioning (Di Scala et al., 1987; Castilho et al., 2002; Kincheski et al., 2012) or that found inactivation of dPAG to block fear conditioning to footshock (Johansen et al., 2010). It is possible that this discrepancy derives from the different experimental designs (gain vs. loss of function), threat stimuli (predator vs. footshock), or species (mice vs. rats; N. Canteras, unpublished data) used. Regardless, our findings are consistent with anatomical theories that place the medial hypothalamus in an intermediate position in the predator fear circuitry, downstream of amygdala and septal inputs that provide multi-modal sensory information about threat, and upstream of dPAG defensive behavior motor outputs (Swanson 2000). Electrophysiological recordings of single units in VMHvl during male-male or male-female interactions in mice revealed firing activity that correlated only weakly with specific sensory inputs or behavioral outputs (Lin et al., 2011; Falkner et al., 2014) consistent with such an intermediate, non-sensory, non-motor role in the instinctive behavioral circuitry. Taken together, these data support the idea that neural activity in VMH serves as a critical part of an internal brain state the promotes instinctive responses and that in humans such activity may underlie the emotions and feelings that we experience when exposed to motivating stimuli.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Zonfrillo, R. Migliozzi, E. Audero, P. Hublitz, E. Amendola, and the EMBL Transgenic Facility and Mechanical Workshop for experimental support and M. Yang, S. Motta and N.S. Canteras for critical advice. We thank A. Illarianova and V. Grinevich for the production and testing of AAVs. This work was supported by funds from the US National Institutes of Health (MH093887-01) and ERC (ERC-2013-ADG 341139) to C.T.G. and from the EMBL to C.T.G., B.A.S., C.M., P.K., R.C. and L.C..

Abbreviations

- AAV

Adeno-associated virus

- Amy

amygdala

- CNO

Clozapine-N-Oxide

- dPAG

dorsal periaqueductal grey

- PMD

dorsal premammillary nucleus

- VMHdm

dorsomedial part of the ventromedial hypothalamus

- HIP

hippocampus

- hM4D

human muscarinic receptor 4 DREADD

- MeA

medial amygdala

- Nr5a1

nuclear receptor 5a1

- hSyn

human synapsin promoter

References

- Aguiar DC, Guimarães FS. Blockade of NMDA receptors and nitric oxide synthesis in the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray attenuates behavioral and cellular responses of rats exposed to a live predator. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:2418–2429. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GM, Rogan SC, Abbas AI, Armbruster BN, Pei Y, Allen JA, Nonneman RJ, Hartmann J, Moy SS, Nicolelis MA, McNamara JO, Roth BL. Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron. 2009;63:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DJ, Adolphs R. A framework for studying emotions across species. Cell. 2014;157:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5163–5168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergan JF, Ben-Shaul Y, Dulac C. Sex-specific processing of social cues in the medial amygdala. Elife. 2014;3:e02743. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard DC, Canteras NS, Markham CM, Pentkowski NS, Blanchard RJ. Lesions of structures showing FOS expression to cat presentation: Effects on responsivity to a Cat, Cat odor, and nonpredator threat. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Hunsperger RW, Rosvold HE. Defense, attack, and flight elicited by electrical stimulation of the hypothalamus of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1969;8(2):113–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00234534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno J, Pfaff DW. Single unit recording in hypothalamus and preoptic area of estrogen-treated and untreated ovariectomized female rats. Brain Res. 1976;101:67–78. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90988-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS. The medial hypothalamic defensive system: hodological organization and functional implications. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:481–491. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Kroon JAV, Do-Monte FHM, Pavesi E, Carobrez AP. Sensing danger through the olfactory system: The role of the hypothalamic dorsal premammillary nucleus. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1228–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Organization of projections from the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: a Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1994;348:41–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Swanson LW. The dorsal premammillary nucleus: an unusual component of the mammillary body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10089–10093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilho VM, Macedo CE, Brandão ML. Role of benzodiazepine and serotonergic mechanisms in conditioned freezing and antinociception using electrical stimulation of the dorsal periaqueductal gray as unconditioned stimulus in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;165:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cezario AF, Ribeiro-Barbosa ER, Baldo MVC, Canteras NS. Hypothalamic sites responding to predator threats - the role of the dorsal premammillary nucleus in unconditioned and conditioned antipredatory defensive behavior. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1003–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi GB, Dong HW, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Swanson LW, Anderson DJ. Lhx6 delineates a pathway mediating innate reproductive behaviors from the amygdala to the hypothalamus. Neuron. 2005;46:647–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Scala G, Mana MJ, Jacobs WJ, Phillips AG. Evidence of Pavlovian conditioned fear following electrical stimulation of the periaqueductal grey in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1987;40:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dielenberg RA, Leman S, Carrive P. Effect of dorsal periaqueductal gray lesions on cardiovascular and behavioral responses to cat odor exposure in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RM, Dragunow M, Robertson HA. High-frequency discharge of dentate granule cells, but not long-term potentiation, induces c-fos protein. Brain Res. 1988;464:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(88)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M, Faull R. The use of c-fos as a metabolic marker in neuronal pathway tracing. J Neurosci Methods. 1989;29:261–265. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Humeau Y, Grenier F, Ciocchi S, Herry C, Lüthi A. Amygdala Inhibitory Circuits and the Control of Fear Memory. Neuron. 2009;62:757–771. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkner AL, Dollar P, Perona P, Anderson DJ, Lin D. Decoding ventromedial hypothalamic neural activity during male mouse aggression. J Neurosci. 2014;34:5971–5984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5109-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner S, Greenberg ME. Ca2+ channel-regulated neuronal gene expression. J Neurobiol. 1998;37:171–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozzi A, Jain A, Giovanelli A, Bertollini C, Crestan V, Schwarz AJ, Tsetsenis T, Ragozzino D, Gross CT, Bifone A. A neural switch for active and passive fear. Neuron. 2010;67:656–666. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross CT, Canteras NS. The many paths to fear. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:651–658. doi: 10.1038/nrn3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubensak W, Kunwar PS, Cai H, Ciocchi S, Wall NR, Ponnusamy R, Biag J, Dong H-W, Deisseroth K, Callaway EM, Fanselow MS, Lüthi A, Anderson DJ. Genetic dissection of an amygdala microcircuit that gates conditioned fear. Nature. 2010;468:270–276. doi: 10.1038/nature09553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess WR, Brügger M. Das subkortikale Zentrum der affektiven Abwehrraktion. Helv Physiol Acta. 1943;1:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SM, Raine L. Protein A, avidin, and biotin in immunohistochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981;29:1349–1353. doi: 10.1177/29.11.6172466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. What is an emotion? Mind. 1884;9:188–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kemble ED, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Effects of regional amygdaloid lesions on flight and defensive behaviors of wild black rats (Rattus rattus) Physiol Behav. 1990;48:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90251-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincheski GC, Mota-Ortiz SR, Pavesi E, Canteras NS, Carobrez AP. The dorsolateral periaqueductal gray and its role in mediating fear learning to life threatening events. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch HS, Charlet A, Hoffmann L, Eliava M, Khrulev S, Cetin A, Osten P, Schwarz M, Seeburg P, Stoop R, Grinevich V. Evoked axonal oxytocin release in the central amygdala attenuates fear response. Neuron. 2012;73:553–566. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunwar PS, Zelikowsky M, Remedios R, Cai H, Yilmaz M, Meister M, Anderson DJ. Ventromedial hypothalamic neurons control a defensive emotion state. eLife. 2015;2015:4, e06633. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurrasch DM, Cheung CC, Lee FY, Tran PV, Hata K, Ingraham HA. The neonatal ventromedial hypothalamus transcriptome reveals novel markers with spatially distinct patterning. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13624–13634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2858-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. Rethinking the Emotional Brain. Neuron. 2012;73:653–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Boyle MP, Dollar P, Lee H, Lein ES, Perona P, Anderson DJ. Functional identification of an aggression locus in the mouse hypothalamus. Nature. 2011;470:221–226. doi: 10.1038/nature09736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp HP, Hunsperger RW. Threat, attack and flight elicited by electrical stimulation of the ventromedial hypothalamus of the marmoset monkey Callithrix jacchus. Brain Behav Evol. 1978;15:260–293. doi: 10.1159/000123782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez RC, Carvalho-Netto EF, Ribeiro-Barbosa ÉR, Baldo MVC, Canteras NS. Amygdalar roles during exposure to a live predator and to a predator-associated context. Neuroscience. 2011;172:314–328. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez RCR, Carvalho-Netto EF, Amaral VCS, Nunes-de-Souza RL, Canteras NS. Investigation of the hypothalamic defensive system in the mouse. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melia KR, Ryabinin AE, Schroeder R, Bloom FE, Wilson MC. Induction and habituation of immediate early gene expression in rat brain by acute and repeated restraint stress. J Neurosci. 1994;14(10):5929–5938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-05929.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta SC, Goto M, Gouveia FV, Baldo MVC, Canteras NS, Swanson LW. Dissecting the brain’s fear system reveals the hypothalamus is critical for responding in subordinate conspecific intruders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4870–4875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900939106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. The neurobiology of emotions: Of animal brains and human feelings. In: Handbook of Social Psychophysiology. Wiley Handbooks of Psychophysiology. 1989:5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Papes F, Logan DW, Stowers L. The vomeronasal organ mediates interspecies defensive behaviors through detection of protein pheromone homologs. Cell. 2010;141:692–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavesi E, Canteras NS, Carobrez AP. Acquisition of Pavlovian fear conditioning using β-adrenoceptor activation of the dorsal premammillary nucleus as an unconditioned stimulus to mimic live predator-threat exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:926–939. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; 2001. pp. 1–350. Available at: papers2://publication/uuid/06D6DDC2-9CE7-4765-8202-DDA77733788C. [Google Scholar]

- Pentkowski NS, Blanchard DC, Lever C, Litvin Y, Blanchard RJ. Effects of lesions to the dorsal and ventral hippocampus on defensive behaviors in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2185–2196. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilpel N, Landeck N, Klugmann M, Seeburg PH, Schwarz MK. Rapid, reproducible transduction of select forebrain regions by targeted recombinant virus injection into the neonatal mouse brain. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;182(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risold PY, Swanson LW. Connections of the rat lateral septal complex. Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:115–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva BA, Mattucci C, Krzywkowski P, Murana E, Illarionova A, Grinevich V, Canteras NS, Ragozzino D, Gross CT. Independent hypothalamic circuits for social and predator fear. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1731–1733. doi: 10.1038/nn.3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. Cerebral hemisphere regulation of motivated behavior. Brain Res. 2000;886:113–164. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02905-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vianna DML, Brandão ML. Anatomical connections of the periaqueductal gray: Specific neural substrates for different kinds of fear. Brazilian J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:557–566. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Davis M. The role of amygdala glutamate receptors in fear learning, fear-potentiated startle, and extinction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:379–392. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Chen IZ, Lin D. Collateral pathways from the ventromedial hypothalamus mediate defensive behaviors. Neuron. 2015;85(6):1344–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilent WB, Oh MY, Buetefisch CM, Bailes JE, Cantella D, Angle C, Whiting DM. Induction of panic attack by stimulation of the ventromedial hypothalamus. J of Neurosurg. 2010;122:1295–1298. doi: 10.3171/2009.9.JNS09577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff SB, Gründemann J, Tovote P, Krabbe S, Jacobson GA, Müller C, Herry C, Ehrlich I, Friedrich RW, Letzkus JJ, Lüthi A. Amygdala interneuron subtypes control fear learning through disinhibition. Nature. 2014;509(7501):453–8. doi: 10.1038/nature13258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.