Abstract

Increased cardiac myocyte contractility by the β-adrenergic system is an important mechanism to elevate cardiac output to meet hemodynamic demands and this process is depressed in failing hearts. While increased contractility involves augmented myoplasmic calcium transients, the myofilaments also adapt to boost the transduction of the calcium signal. Accordingly, ventricular contractility was found to be tightly correlated with PKA-mediated phosphorylation of two myofibrillar proteins, cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI), implicating these two proteins as important transducers of hemodynamics to the cardiac sarcomere. Consistent with this, we have previously found that phosphorylation of myofilament proteins by PKA (a downstream signaling molecule of the beta-adrenergic system) increased force, slowed force development rates, sped loaded shortening, and increased power output in rat skinned cardiac myocyte preparations. Here, we sought to define molecule-specific mechanisms by which PKA-mediated phosphorylation regulates these contractile properties. Regarding cTnI, the incorporation of thin filaments with unphosphorylated cTnI decreased isometric force production and these changes were reversed by PKA-mediated phosphorylation in skinned cardiac myocytes. Further, incorporation of unphosphorylated cTnI sped rates of force development, which suggests less cooperative thin filament activation and reduced recruitment of non-cycling cross-bridges into the pool of cycling cross-bridges, a process that would tend to depress both myocyte force and power. Regarding MyBP-C, PKA treatment of slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers caused phosphorylation of MyBP-C (but not slow skeletal TnI (ssTnI)) and yielded faster loaded shortening velocity and ~30% increase in power output. These results add novel insight into the molecular specificity by which the β-adrenergic system regulates myofibrillar contractility and how attenuation of PKA-induced phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and cTnI may contribute to ventricular pump failure.

Keywords: cardiac myocyte, ventricular power output, ventricular function curve, myosin binding proteins, cardiac troponin I, sarcomere length

Introduction

The mammalian heart has an astonishing capability to vary its pumping capacity from second-to-second. The heart alters ventricular stroke output by fluctuating both physical and activation factors in each individual cardiac myocyte. For instance, increased ventricular filling yields more optimal myofilament lattice properties (9) that increase the propensity for myosin cross-bridges to transition from non-force generating states to force generating states. In addition, ligand binding to beta1 (β1)-adrenergic receptors increases the intracellular calcium transient [Ca2+]i (12), which also increases the probability of force generating myosin cross-bridges. The increase in [Ca2+]i by β1-adrenergic stimulation is mediated by 3’-5’ cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of calcium handling proteins including the sarcolemmal L-type Ca2+ channel, the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), and the SR protein, phospholamban (3). In addition, PKA has multiple substrates within the myofilaments including titin (71), the thick filament protein cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) (8, 19, 20, 58), and the thin filament protein cardiac troponin I (cTnI) (60, 61, 64). Thus, β1-adrenergic stimulation launches a highly coordinated, diverse array of post-translational modifications (PTMs) of calcium handling proteins and myofilament proteins, all of which precisely interact to optimize ventricular pump function. One potential interface molecule between augmented [Ca2+]i and myofibrillar function is cTnI. Phosphorylation of cTnI at serines 23/24 is known to reduce the affinity of cardiac troponin C (cTnC) for Ca2+; this likely assists myofilament deactivation, which is especially important given the elevated [Ca2+]i transient and the higher heart rates (and the consequent diminished diastolic time interval) due to β1-adrenergic stimulation. This mechanism would help retain adequate diastolic filling and keep cardiac myocytes working at ideal lengths (i.e., physical environment) during each heartbeat. While there is overwhelming evidence in support of this mechanism (i.e., decreased Ca2+ sensitivity of force in response to PKA mediated phosphorylation of cTnI (10, 30, 33–35, 56, 63, 67)), we consider it to be only one of several myofilament alterations elicited by PKA-mediated phosphorylation that adjust ventricular performance to meet hemodynamic demand. Consistent with this, we have found that PKA treatment of permeabilized rat cardiac myocyte preparations not only decreases Ca2+ sensitivity of isometric force (24, 26, 27, 30), it also (i) increases maximal Ca2+-activated force (30), (ii) decreases the rate of force development (which we theorize to result from enhanced recruitment of cross-bridges (26, 27), (iii) increases both maximal and half-maximal Ca2+-activated power output (27, 30), (iv) increases shortening-induced cooperative deactivation (44, 45) and (v) augments length dependence of force generation (24, 26). These results have been consolidated into our working model whereby PKA-mediated phosphorylation of myofilament proteins augments contractility by increased cooperative activation of the thin filament following Ca2+ binding to cTnC and enhanced cooperative deactivation of the thin filament upon myocyte shortening to help assist with myocyte/ventricular relaxation (24–26, 39, 44). If this model, which was derived, for the most part, from biophysical experiments on rat skinned cardiac myocytes, is correct then rat ventricular contractility should correlate with PKA-mediated phosphorylation of myofibrillar proteins. Thus, we hypothesized that rat left ventricular power output at any given pre-load will increase as a function of either PKA-mediated cMyBP-C or cTnI phosphorylation levels or both.

Next, since PKA has multiple myofibrillar substrates (i.e., titin, cMyBP-C, and cTnI) we attempted to define molecular-specificity of functional changes induced by PKA-mediated post-translational modifications (PTMs). For these experiments, we returned to rat skinned cardiac myocyte or slow-twitch skeletal muscle fiber preparations and utilized a troponin complex exchange protocol to help isolate PTM molecule specificity in the control of three key determinants of ventricular stroke performance, i.e., force, rate of force development, and power output.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Experimental Animals

All procedures involving animal use were performed according to the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (6 weeks of age) were obtained from Harlan (Madison,WI), housed in groups of two, and provided access to food and water ad libitum. A group of rats were treated with propranolol for 7 days by adding 50 mg to 1L of H20 and age matched with control rats.

Solutions

Perfusion buffer for whole heart experiments contained the following (in mmol/L): 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.25 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 H2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 0.5 Na-EDTA, 11 glucose, 0.4 octanoic acid, 1 pyruvate; plus 0.1% bovine serum albumin (dialyzed against 40–50 volumes of the preceding buffer salt solution).

Whole Heart Cannulation

Hearts were removed and the aorta was cannulated and perfused with oxygenated perfusion buffer for 10 min in a Langendorff apparatus. The pulmonary vein was then cannulated, and hearts were switched to a working heart system at the perfusate temperature that was set at 34°C as previously reported (38, 57). Heart rate, blood pressure, aortic flow, and coronary flow were measured at varied preloads both before and (in some preparations) after administration of 0.1 mM epinephrine. Afterload was kept constant at ~80 cm H2O throughout the experiments. The preload protocol was 3, 5, 7.5, 10, and 15 (cm H20) to characterize ventricular function curves.

Recombinant Troponin

Rat cardiac troponin C (cTnC), troponin I (cTnI), and troponin T (cTnT) cDNA was isolated as previously described (37). cDNA encoding the adult myc-tagged rat cTnT was generated by PCR addition of an N-terminal myc-tag (MMEQKLISEEDL) prior to Ser-2. The individual recombinant rat cTn subunits were expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity as previously described for the human cTn subunits (50, 51). Recombinant (R) troponin complex used for exchange contained adult rat cTnC, cTnI, and cTnT with an N-terminal myc-tag.

Cardiac myocyte and skeletal muscle fiber preparations

Myocytes were obtained by mechanical disruption of rat hearts as previously described (43). Skeletal muscle fibers were obtained from Sprague-Dawley rats anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane (20% (vol/vol) in olive oil) and slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers were obtained from the soleus muscle as previously described (43).

Experimental apparatus

The experimental apparatus for mechanical measurements of myocyte preparations and skeletal muscle fibers was the same as previously described (43, 46). Prior to mechanical measurements the experimental apparatus was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (model IX-70, Olympus Instrument Co., Japan), which was placed upon a pneumatic vibration isolation table. Mechanical measurements were performed using a capacitance-gauge transducer (Model 403-sensitivity of 20 mV/mg (plus a 10x amplifier for cardiac myocytes) and resonant frequency of 600 Hz; Aurora Scientific, Inc., Aurora, ON, Canada). Length changes were introduced using a DC torque motor (model 308, Aurora Scientific, Inc.) driven by voltage commands from a personal computer via a 12- or 16-bit D/A converter (AT-MIO-16E-1, National Instruments Corp., Austin, TX, USA). Force and length signals were digitized at 1 kHz and stored on a personal computer using LabView for Windows (National Instruments Corp.). Sarcomere length was monitored simultaneous with force and length measurements using IonOptix SarcLen system (IonOptix, Milton, MA), which used a fast Fourier transform algorithm of the video image of the myocyte.

Solutions

Compositions of relaxing and activating solutions used in mechanical measurements were as follows: 7 mM EGTA, 1 mM free Mg2+, 20 mM imidazole, 4 mM MgATP, 14.5 mM creatine phosphate, pH 7.0, various Ca2+ concentrations between 10−9 M (relaxing solution) and 10−4.5 M (maximal Ca2+ activating solution), and sufficient KCl to adjust ionic strength to 180 mM. The final concentrations of each metal, ligand, and metal-ligand complex were determined with the computer program (15). Relaxing solution in which the ventricles were mechanically disrupted and myocytes and skeletal muscle fibers were re-suspended contained 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, 10 mM imidazole, and 100 mM KCl at pH 7.0 with the addition of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Set I Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Troponin exchange was carried out in relaxing solution containing ~0.5mg/ml recombinant troponin complex.

Skinned cardiac myocyte/skeletal muscle fiber mechanical measurements

All mechanical measurements on cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle fibers were performed at 13 ± 2°C. Following attachment, the relaxed preparation was adjusted to a sarcomere length of ~2.30 μm. For tension-pCa relationships, the preparation was first transferred into pCa 4.5 solution for maximal activation and subsequently transferred into a series of sub-maximal activating pCa solutions. At each pCa, steady-state tension was allowed to develop and the cell was rapidly slackened to determine total tension. The amount of active tension was calculated as the difference between total tension and passive tension, which was assessed by slackening the preparation in the relaxed state. Tensions in sub-maximal activating solutions were expressed as a fraction of tension obtained during maximal calcium activation. The maximal tension value used to normalize sub-maximal tensions was obtained by linear interpolation between maximal activation made at the beginning and end of the protocol.

For sarcomere length dependence of force development rates, cell preparations were transferred to a pCa solution that yielded ~50% maximal force and then the rates of force redevelopment were measured over a range of sarcomere lengths monitored by the IonOptix SarcLen system (IonOptix, Milton, MA). Sarcomere length was adjusted between ~2.50 μm and ~1.60 μm (by ~0.10 μm intervals) by manual manipulation of the length micrometer while the preparation was Ca2+ activated. After each sarcomere length change ~10–15 seconds were provided to allow for development of steady-state force. At each sarcomere length, the kinetics of force re-development were obtained using a procedure previously described for skinned cardiac myocyte preparations (27, 32, 40). While in Ca2+ activating solution, the preparation was rapidly shortened by 10–20% of initial length (Lo) to yield zero force. The preparation was then allowed to shorten for ~20 ms, after which the preparation was rapidly re-stretched to ~105% of its initial length (Lo) for 2 ms and then returned to Lo. To assess the effects of incorporation of unphosphorylated cTnI and/or PKA on force and rate of force redevelopment, the aforementioned sarcomere length-tension relationships were performed after cTn exchange (in relaxing solution for 2 to 12 hours) and/or 45 min incubation with PKA (Sigma, 0.5 U/μl).

Force-velocity and power-load measurements were performed as previously described (43) at 13 ± 2°C. The muscle fiber preparations were kept in submaximal Ca2+ activating solution for 3–4 minutes during which 10–20 force clamps were performed without significant loss of force. After obtaining a force-velocity relationship, the preparation was activated again in maximal Ca2+ activation solution and if force fell below 80% of initial force, data from that myocyte were discarded.

SDS-PAGE, western blots, autoradiography

To assess troponin exchange cardiac myofibrillar proteins were assessed using SDS-PAGE followed by Western blots using a monoclonal TnT antibody (DSHB, Iowa City, IA) since RcTnT contained a myc-tag that slowed its migration pattern compared to endogenous TnT. This differential gel migration pattern provided a way to quantify cTnT exchange, which served as an index for extent of exchange of the entire Tn complex.

To examine PKA substrates by autoradiography, myofibrillar samples were prepared from a subpopulation (4 from each group) of control, epinephrine treated hearts, and hearts from propranolol treated rats and then incubated with the catalytic subunit of PKA in the presence of radio-labelled ATP, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography as previously described (26). Briefly, 10 μg of skinned cardiac myocytes were incubated with the catalytic subunit of PKA (2.5 U/μl) and 50 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP for 30 minutes. The reaction was stopped by the addition of electrophoresis sample buffer and heating at 95°C for 3 min. The samples were then separated by SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide), silver stained, dried, and subsequently exposed to x-ray film for ~24 hours at −70°C. To quantify the level of PKA-induced back phosphorylation, MyBP-C and cTnI bands on the x-ray film were scanned and band intensity was measured by densitometry and adjusted for protein load as assessed by silver-stain bands. The phosphoryl incorporation was normalized to the control densitometric values and the inverse of these values was plotted in Figure 1. To examine myofibrillar substrates of PKA in rat soleus slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers, myofibrillar samples were incubated with the catalytic subunit of PKA in the presence of radiolabeled ATP, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography (Figure 4B).

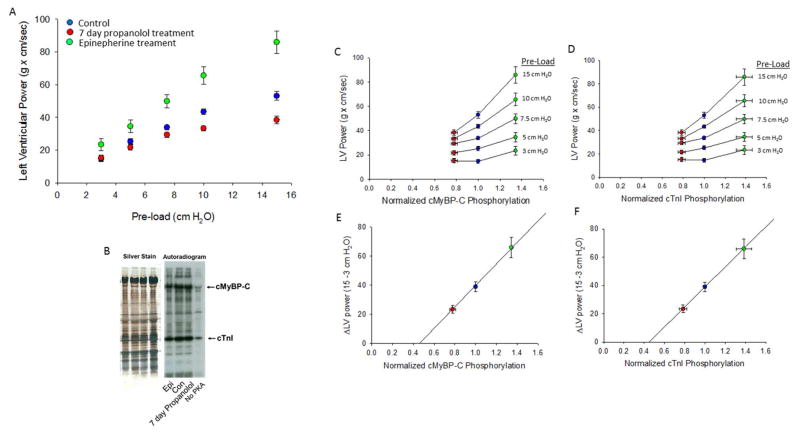

Figure 1. Relationship between isolated rat heart left ventricular (LV) power output and normalized PKA-mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and cTnI.

(A) LV power increased at greater pre-loads. The LV versus pre-load relationship (i.e., ventricular function curve) was most shallow in hearts from rats treated for 7 days with propranolol (n=9), intermediate in hearts from control (untreated) rats (n=14), and steepest in isolated hearts treated with epinephrine (0.1 mM) (n=8). (B). Silver-stained SDS-PAGE and autoradiogram. Cardiac myofibrils were isolated from hearts and treated with (0.1 U/μl) PKA (except last lane) for 45 minutes. PKA-mediated back phosphorylation was assessed by densitometric analysis of exposed bands on film and normalized to protein load from silver stained gel. (C & D) Relationship between LV power and normalized cMyBP-C and cTnI phosphorylation at each pre-load. (E & F) Relationship between change in LV power (ΔLV Power) and normalized cMyBP-C and cTnI phosphorylation.

Figure 4. Effect of MyBP-C phosphorylation of power output in a rat skinned slow-twitch skeletal muscle fiber.

(A). Following PKA treatment, loaded shortening and power output were increased at all relative loads, suggesting that PKA-mediated phosphate incorporation in MyBP-C regulates striated muscle power output. Inset shows myocyte length (top) and force (bottom) traces during load clamps. Bar plot shows mean (±SEM) power output for 4 slow-twitch skeletal muscle fiber preparations before and after PKA (*p < 0.05). (B). Silver-stained SDS-PAGE and autoradiogram of slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers indicating that MyBP-C, but not ssTnI, is phosphorylated by PKA.

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Left ventricular (LV) power was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

Relative phosphate incorporation was calculated using Image J software to determine protein specific band intensity normalized to total protein load. The relationship between ventricular function curves and cMyBP-C and cTnI phosphate content was examined by linear regression. Tension-pCa data were fit by a computer using least-squares regression analysis of the following equation:

| (2) |

where Pr is tension as a fraction of maximal calcium activated tension measured in pCa 4.5 solution (P4.5) and n is the Hill coefficient. Force redevelopment following a slack-restretch maneuver was fit by a single exponential equation:

| (3) |

where F is tension at time t, Fmax is maximal tension, and ktr is the rate constant of force development. Myocyte length traces, force-velocity curves, and power-load curves were analyzed as previously described (43). Myocyte length and sarcomere length traces during loaded shortening were fit to a single decaying exponential equation:

| (4) |

where L is cell length at time t, A and C are constants with dimensions of length, and k is the rate constant of shortening (kshortening). Velocity of shortening at any given time, t, was determined as the slope of the tangent to the fitted curve at that time point. In this study velocities of shortening were calculated by extrapolation of the fitted curve to the onset of the force clamp (i.e., t = 0). Hyperbolic force-velocity curves were fit to the relative force-velocity data using the Hill equation (31)

| (5) |

where P is force during shortening at velocity V; Po is the peak isometric force; and a and b are constants with dimensions of force and velocity, respectively. Power-load curves were obtained by multiplying force x velocity at each load on the force-velocity curve. Curve fitting was performed using a customized program written in Qbasic, as well as commercial software (Sigmaplot).

RESULTS

Isolated Rat Heart Experiments

Ventricular function curves were characterized from hearts isolated from control rats and rats provided propranolol treated water for 7 days. Hearts from control rats (n=14) exhibited greater LV power at all pre-loads above 3 cm H2O and displayed a steeper ventricular function curve compared to hearts from propranolol treated animals (n=9) (Figure 1A). When hearts were treated acutely with epinephrine (5 control hearts and 3 hearts from propranolol treated rats) LV power was augmented at each pre-load and the ventricular function curve became considerably steeper (Figure 1A). Since numerous skinned cardiac myocyte experiments have shown increased contractile properties following PKA treatment (including increased maximal force (26, 30), power output (27, 30) and length dependence of both force (24, 26) and power (27)), we tested the hypothesis that both LV power output and the steepness of ventricular function curves would increase as a function of PKA-mediated phosphorylation of cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) and cardiac troponin C (cTnI). To examine the relation between LV power and phosphate incorporation into cMyBP-C and cTnI, working hearts were frozen with liquid nitrogen immediately following completion of functional assessment. Cardiac myofibrils were isolated and autoradiography was performed to assess baseline phosphate content in cMyBP-C and cTnI by PKA-mediated back-phosphorylation assays using radiolabelled ATP (Figure 1B). For this assay, silver-stained gels were used to normalize relative autoradiography signal with cMyBP-C and cTnI protein load in each gel lane. Figure 1C and 1D shows the relationship between LV power at each pre-load and normalized cMyBP-C and cTnI PKA-mediated phosphorylation, respectively. LV power was greater at each pre-load (except in control hearts at 3 cm H2O) with increasing cMyBP-C and cTnI phosphorylation. Figure 1E and 1F shows the relationship between the change in LV power (ΔLV Power) and normalized cMyBP-C and cTnI phosphorylation, respectively. The ΔLV Power increased as PKA-mediated phosphate content in cMyBP-C and cTnI increased; consistent with the idea that both PKA mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and cTnI modulates cardiac myocyte contractility and its length dependence.

Skinned striated muscle cell preparation experiments

Isometric force

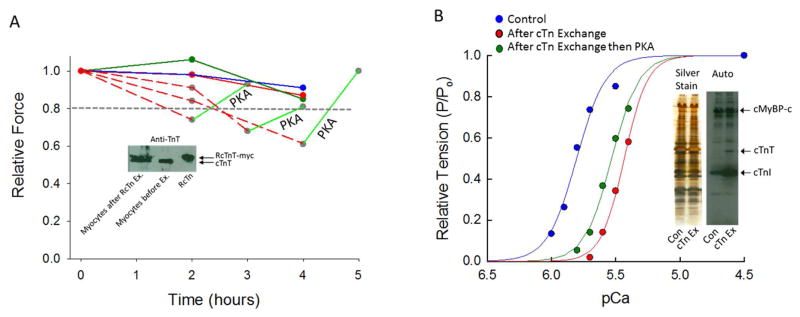

Given the aforementioned finding of a tight correlation between LV power and PKA-mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and cTnI, we undertook a systematic investigation of PTM molecular-specificity of force, rate of force development, and power modulation. First, we addressed the role of cTnI phosphate content on isometric force. We focused on cTnI since we recently discovered that cTnI phosphorylation at the putative PKA substrate amino acids (i.e., serines 23/24) controlled the length dependence of force generation (24). These studies were able to focus on cTnI phosphorylation specifically by exchange of endogenous cTn for exogenous recombinant (R) cTn complex, which lacks any post-translation phosphate incorporation due to its expression in bacterial cells but RcTnI is readily phosphorylated by PKA (24). Typically, 2–4 hours of RcTn exchange resulted in ~50% cTn incorporation (Figure 2 inset) and a partial decline (<20%) in maximal Ca2+-activated force (24). In addition, timed experiments using either control (non-cTn exchanged) myocyte preparations or cardiac myocyte preparations that underwent cTn exchange with RcTn pre-treated with PKA also yielded a minimal decline in force (i.e., <20%) (Figure 2A). However, in a subset of cardiac myocyte preparations that underwent exchange with (unphosphorylated) RcTn complex, there was a greater fall in maximal Ca2+-activated force (> 20%) (Figure 2A). Interestingly, maximal Ca2+ force returned to near pre-exchange values after PKA treatment (Figure 2A). In a separate series of experiments, an aliquot of skinned cardiac myocytes underwent RcTn exchange for ~12 hours then a myocyte was selected and attached to the mechanical apparatus and the tension-pCa relationship characterized. The preparation was then treated with PKA, which resulted in an increase of isometric force at all levels of Ca2+ activation (Figure 2B). This was surprising since PKA typically decreases Ca2+ sensitivity of force (18). However, control experiments indicated that, while PKA treatment increased Ca2+ sensitivity of force in myocyte preparations that had undergone overnight RcTn exchange, the tension-pCa relationship after PKA was still significantly right-shifted (i.e., less Ca2+ sensitivity of force) than the tension-pCa relation in a control cardiac myocyte preparation (Figure 2B). We also assessed the phosphate content of myofibrillar proteins from cells that underwent cTn complex exchange compared to control skinned cardiac myocytes. Importantly, the RcTn exchange level of baseline cTnI phosphorylation was markedly reduced (as evidenced by much greater PKA-induced back phosphorylation) compared to control skinned cardiac myocytes. Interestingly, RcTn exchange did not appear to affect baseline cMyBP-C phosphorylation. However, cTnT phosphorylation also was reduced in the cTn-exchanged skinned cardiac myocytes, which may contribute to the Ca2+ sensitivity shift of tension observed in response to PKA (Figure 2B inset).

Figure 2. Effect of cTn exchange on Ca2+ activated isometric force in different rat skinned cardiac myocyte preparations.

(A). Typically 2–4 hours of exchange with unphosphorylated recombinant (R) cTn (solid red line) or cTn complex pre-treated with PKA (dark green circles) resulted in ~ 50% RcTn incorporation and less than a 20% reduction in maximal Ca2+-activated force. However, in a subset of rat permeabilized cardiac myocyte preparations that underwent exchange with un-phosphorylated cTn complex there was a marked fall (> 20%) in maximal Ca2+-activated force (dashed red lines), which could, in part, be recovered by PKA. (The inset shows a troponin T (TnT) western blot of rat skinned cardiac myocytes before and after RcTn complex exchange, whereby RcTnT contains a myc-tag resulting in slightly slower migration in the SDS-gel.) (B). After overnight RcTn exchange, PKA treatment resulted in an unexpected leftward shift in the tension-pCa relationship (i.e., greater relative force at each level of Ca2+ activation). (This experiment was repeated on 5 different skinned cardiac myocyte preparations). A control tension-pCa relationship is plotted (blue line) to illustrate that while PKA increased Ca2+ sensitivity of force in myocyte preparations that underwent overnight cTn complex exchange, the tension-pCa relationship after PKA was significantly less sensitive to Ca2+ compared to the control cardiac myocyte preparation. The inset shows an autoradiogram demonstrating PKA-induced phosphate incorporation in control skinned cardiac myocytes and myocytes that underwent overnight RcTn complex exchange. RcTn exchange significantly reduced the baseline cTnI phosphorylation (as evidenced by increased back-phosphorylation) compared to control.

Rate of force development

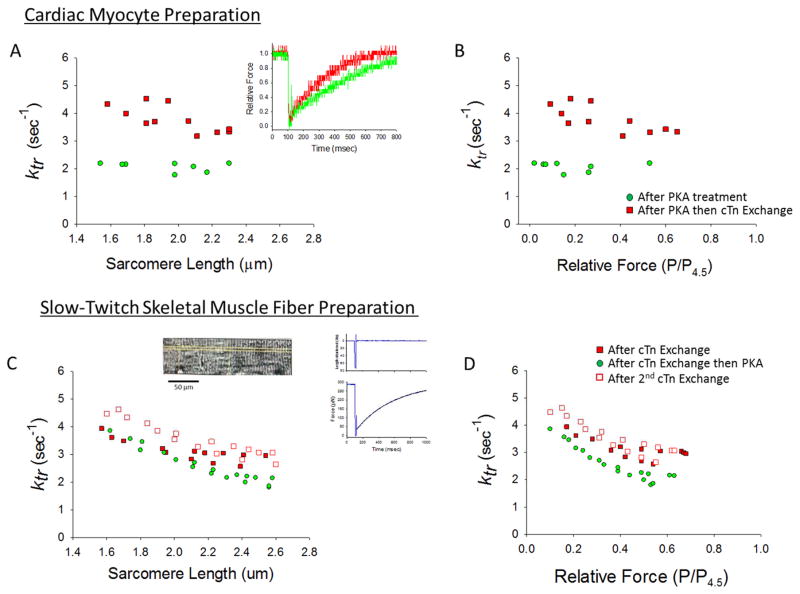

Another key physiological factor that determines ventricular ejection is the rate of ventricular pressure development. The rate of ventricular pressure development is mechanistically determined by the rate of force development in individual cardiac myocytes. The rate of force development has been systematically investigated in skinned cardiac muscle preparations and has been found to be faster with increased activator calcium (11, 17, 21, 55, 66, 70), faster at shorter sarcomere lengths (1, 26, 27, 39, 48, 52) and either increased (16, 22, 62) or decreased (26, 27) after PKA-mediated phosphorylation of myofilament proteins. Regarding the latter variable, our laboratory consistently has observed slower force development rates following PKA treatment of rat skinned cardiac myocyte preparations. We have interpreted these results in the context of a model whereby the rate of force development is limited by the rate of recruitment of cross-bridges from the non-cycling, non-force generating pool to the active force generating pool (6). In this context, slower rates of force development (i.e., lower ktr) with PKA is thought to reflect increased cooperative activation of the thin filament and greater recruitment of cross-bridges. We attempted to define the molecular specificity of PKA regulation of ktr by utilizing cTn exchange protocols in rat skinned cardiac myocyte and slow-twitch skeletal muscle fiber preparations. Since we routinely observe that PKA decreases ktr, we tested the hypothesis that incorporation of unphosphorylated RcTnI would speed ktr. Figure 3A & 3B shows the effects of RcTn exchange on rate constant of force development in a rat skinned cardiac myocyte. For this experiment the cardiac myocyte preparation was first treated with PKA and rate of force development was measured over a range of sarcomere lengths (green circles). Next the myocyte preparation underwent RcTn exchange, and consistent with our hypothesis, ktr was greater at all sarcomere lengths (Figure 3A) and at all relative force levels (Figure 3B); these results suggest that cTnI phosphorylation per se is sufficient to slow the rate of force development.

Figure 3. Effects of unphosphorylated RcTn exchange on rate constant of force development (ktr) in skinned rat cardiac myocytes and slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers.

(A & B) A skinned cardiac myocyte preparation was first treated with PKA and the rate of force development was measured over a range of sarcomere lengths (green circles). Then the skinned myocyte preparation underwent exchange with unphosphorylated RcTn, which increased ktr at all sarcomere lengths (A) and relative force levels (B). Inset in A shows force redevelopment traces in a myocyte preparation with unphosphorylated cTnI and PKA induced phosphorylated cTnI. (This experiment was performed on 4 myocyte preparations). (C & D) In a skinned slow-twitch skeletal muscle fiber, the sarcomere length (C) and relative force (D) dependence of ktr was sequentially measured after an initial 12 hours of exchange with unphosphorylated RcTn (filled red squares), then after the fiber was treated with PKA (this decreased ktr) (green circles), and then after an additional 12 hours of RcTn exchange (which returned ktr to higher values) (open red squares). Inset shows an image of a slow-twitch skeletal muscle fiber and a force redevelopment trace after a slack-restretch maneuver. (This experiment was performed on 4 slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers).

The cTnI molecule-specific mechanism was further tested in rat slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers. Mammalian slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers contain slow skeletal troponin I (ssTnI) that lacks the putative PKA phosphorylation sites at residues ser23/24, but it does contain a MyBP-C isoform that can be phosphorylated by PKA (see Figure 4B). For these experiments, the sarcomere length dependence of ktr first was measured after 12 hours of RcTn exchange (closed red squares) and then again following PKA treatment (green circles). PKA treatment, here again, slowed ktr at all relative force levels (Figure 3D). Next, after an additional 12 hours of RcTn exchange to remove PKA phosphorylated cTnI ktr increased; this reversibility adds additional support to the idea that cTnI phosphorylation alone is sufficient to modulate rates of force development.

Loaded Shortening and Power Output

A final series of experiments were designed to test PKA-phosphorylation molecule specific effects on loaded shortening and power output. We previously observed that PKA sped loaded shortening velocity and increased power output in skinned cardiac myocyte preparations (in concert with its phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and cTnI) (27, 30). In the present study, we tested molecular specificity by again taking advantage of the finding that PKA phosphorylated MYBP-C but does not phosphorylate TnI in slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers (Figure 4B). If PKA mediated phosphorylation of MyBP-C alone can control loaded shortening and power output then PKA should speed loaded shortening and increase power output. Figure 4 shows force-velocity and power-load curves in a slow-twitch skeletal muscle fiber before and after PKA treatment. Notably, PKA sped loaded shortening and increased power output at all relative loads. Peak normalized power output increased from 0.042 ± 0.008 before PKA to 0.053 ± 0.019 ML/(sec * P/Po) after PKA (n = 4, p < 0.05). These results imply that PKA-mediated phosphate incorporation into MyBP-C per se regulates striated muscle power output.

DISCUSSION

The mammalian heart is a highly adaptable and efficient pump that can vary its stroke volume ~5-fold from beat-to-beat. The ventricles have two primary mechanisms to increase stroke volume; one is intrinsic via an increase in sarcomere strain; the other is extrinsic via an increase in β-adrenergic stimulation. Both of these phenomena have been investigated broadly yet the underlying mechanism(s) remain unknown. The purpose of this study was to investigate potential molecular mechanisms by which cardiac myofilaments augment ventricular contractility in response to β-adrenergic stimulation.

Previous studies also observed a correlation between amphibian and mammalian ventricular function and cMyBP-C (19, 28, 29, 36) and cTnI (13, 14, 19, 61) phosphate content. The current study is consistent with these previous studies with the added element of pre-load (length) dependence of ventricular performance correlating with cMyBP-C and cTnI phosphorylation. Recent work in our laboratory has shown that PKA-mediated phosphorylation of cardiac myofilaments steepens the sarcomere length tension relationship and cTnI phosphorylation alone was able to control length-tension relationships (24, 26). As mentioned above, there was a tight correlation between cTnI phosphate content and the steepness of ventricular function curves of isolated rat hearts. The finding that these two parameters were highly correlated suggests that shifts in sarcomere length-tension relationships at the myofilament level by covalent modulation of cTnI (22, 24) translate to ventricular function. However, this deduction is based on correlative data and certainly does not prove that cTnI phosphorylation alone is sufficient to alter the steepness of ventricular function curves. In fact, the finding that ventricular function curve steepness and cMyBP-C phosphate content yield the same correlation suggests a multi-factorial combination of PTMs may be necessary to tune the steepness of the Frank-Starling relationship. Another limitation of this study is that epinephrine was used to activate the β-adrenergic system but its effects via the α-adrenergic system was not assessed.

β-adrenergic stimulation also may alter the steepness of ventricular function curves in isolated rat hearts via other cellular mechanisms. The downstream signaling molecule of the β-adrenergic system (i.e., PKA) includes cardiac myocyte Ca2+ handling proteins among its substrates. PKA-mediated alterations to intracellular calcium may increase contractility to a greater extent at high-end diastolic volumes than at low-end diastolic volumes, resulting in a steeper ventricular function curve exclusive of myofilament responses. However, this example is in disagreement with the myofibrillar sarcomere length-tension relationship, which progressively becomes more shallow with increased calcium activation (2) and would be predicted to reduce the steepness of the ventricular function curves as the curves shift upward. On the contrary, epinephrine treatment increased the steepness of the ventricular function curve and propranolol treatment decreased the slope of ventricular function curves. The integration of these results gives credence that a complex interplay is needed between PKA phosphorylation of both calcium handling proteins and myofilament proteins to align contractility and the steepness of ventricular function. The coordinated phosphorylation of calcium handling proteins and cTnI may be needed to optimize ventricular filling volumes to keep the ventricle generating optimal power (e.g., high up the ventricular function curve) during β-adrenergic stimulation.

A second goal of this study was to define the molecular specificity by which PKA mediated phosphorylation increases ventricular contractility (i.e., increased LV power at a given pre-load). For this aim, we used (i) rat skinned cardiac myocyte preparations, (ii) slow-twitch skeletal muscle fiber preparations, and (iii) implemented our troponin exchange protocol to help isolate molecule specificity in control of three key determinants of ventricular stroke performance, i.e., force, rate of force development, and power output.

Previously, we have observed that PKA slightly increased maximal calcium activated force (30). We tested the molecular specificity of this response by exchanging endogenous troponin from skinned cardiac myocyte preparations with recombinant troponin that contains unphosphorylated cTnI. We found that in a subset of myocyte preparations force fell considerably (i.e., greater than 20%) and subsequent PKA treatment resulted in a substantial recovery of force. This implicates that PKA-mediated phosphorylation plays a fundamental role in the Ca2+ regulation of force in cardiac myofilaments and suggests that a critical mass of phosphate must be incorporated into PKA sites of cTnI (and maybe even cTnT (Figure 2B insert)) to retain optimal Ca2+ regulation of force generation. Interestingly, cTnI phosphate content is often depressed in cardiac myofilaments from heart failure patients (4, 47, 65, 69, 72), which may arise pathophysiologically by decreased β-adrenergic receptors (4) and/or pharmacologically by β-adrenergic receptor blockade therapy (5). While the etiology of the heart failure is multi-factorial it seems plausible that a decline in cTnI phosphate may contribute, at least in part, to depressed systolic function in heart failure patients and seems to be a rationale molecular target for small molecule therapy to improve pump function.

During the isovolumic phase of the cardiac cycle, cardiac myocytes are electrically activated and generate force, giving rise to an increased ventricular pressure. Importantly, the rate and extent of ventricular pressure is thought to be limited by the rate of force development in cardiac myofilaments. We and others have previously observed PKA to decrease the rate of force development in rat skinned cardiac myocyte/myofibril preparations during both maximal and half-maximal calcium activations (26, 27, 54). Consistent with our previous findings whereby PKA-mediated phosphorylation decreased ktr, we found that unphosphorylated cTnI sped the rates of force development (Figure 3A and B) in skinned cardiac myocyte preparations. PKA treatment also slowed force development rates in slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers containing RcTnI and, importantly, this decrease in ktr values was reversed by a second 12 hour exchange with unphosphorylated RcTn. These results are consistent with a model whereby cTnI phosphate incorporation increases the extent of cooperative thin filament activation along the half-sarcomere, which has been modeled to be the rate-limiting step in myofibrillar force development (6). Physiologically, this would be ideal for enhanced activation of thin filaments after β-adrenergic stimulation, which would augment the number of force-generating cross-bridges during a twitch.

Last, we investigated the molecular specificity of the previously reported PKA-mediated increase in loaded shortening velocity and power output in skinned cardiac myocyte preparations (27, 30). The extent of loaded shortening (i.e., power generation) by individual cardiac myocytes ultimately determines stroke volume and, thus, its molecular control is an ideal therapeutic target for diseased ventricles. Here, we used rat skinned slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers to test the molecular specificity of control of loaded shortening and power output by taking advantage of the fact that PKA phosphorylates the slow skeletal isoform of MyBP-C but not slow skeletal (ss)TnI. PKA treatment of slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers resulted in faster loaded shortening and greater power output at all relative loads suggesting that PKA-mediated MyBP-C phosphorylation yields faster loaded shortening. This result does not exclude a role for cTnI phosphorylation but, rather, implicates an important role for cMyBP-C phosphorylation in the regulation of striated muscle power output. The biophysical mechanisms for this effect are unclear but may involve, at least in part, attenuation of a load imposed by MyBP-C interacting with actin and/or myosin cross-bridges (42, 49, 59, 68). This potential mechanism is consistent with previous findings whereby actin filament sliding was slowed in the C zone (i.e., cMyBP-C containing) region of the thick filaments and the cMyBP-C phosphate content modulated this slowdown (53). Overall, the results are consistent with a model whereby MyBP-C creates an internal load that impedes shortening and this load can be reduced by MyBP-C phosphorylation and provides a working hypothesis as to why cMyBP-C phosphorylation correlated with and perhaps contributed to increased LV power. It is important to point out the phosphorylation of cMyBP-C may speed loaded shortening velocities independent of internal loads perhaps, by increasing the radial and azimuthal movement of cross-bridges (7, 23, 41) and these cross-bridges could help sustain activation of the thin filament during loaded shortening permitting more cycling cross-bridges work against the afterload. The discernment of the biophysical mechanism(s) by which MyBP-C and its phosphorylation modulates loaded shortening and power output necessitates additional experimentation.

In summary, this study showed a correlation between the steepness of ventricular function curves and PKA mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and cTnI. These findings suggest that the greater length dependence of force generation in response to PKA in skinned cardiac myocyte preparations (24, 26) translates to isolated working hearts in the form of steeper ventricular function curves following β-adrenergic stimulation. Second, skinned cardiac myocyte studies suggest that if cTnI phosphate content falls to critically low levels, then normal Ca2+ regulation of myofibrillar force is disrupted. Third, PKA phosphorylation of cTnI slows rates of force development and, fourth, PKA phosphorylation of cMyBP-C per se increases myofibrillar power. Overall, these results are consistent with the conceptual model whereby PKA-mediated phosphorylation of cTnI increases the cooperative activation of force development by augmenting the functional length of the Tn-Tm-actin unit, which would tend to speed loaded shortening and increase stroke volume by yielding more force-generating cross-bridges to work against an afterload. This may, superficially, seem counter-intuitive since PKA decreases Ca2+ sensitivity of isometric force; however, the combination of greater [Ca2+]i (in response to PKA phosphorylation of calcium handling proteins) and increased cooperativity of myofilament activation after PKA likely offsets the decrease in calcium sensitivity, consistent with greater isometric force levels in myocardial preparations after β1-adrenergic stimulation (12). In addition to more cooperative activation and more cycling cross-bridges due to cTnI phosphorylation, PKA phosphorylation of cMyBP-C per se tends to further augment loaded shortening and power output by perhaps reducing internal loads that cross-bridges must work against. Considered together, these results imply that a precise combinatorial extent of phosphate content into both calcium handling and sarcomeric proteins in cardiac myocytes is necessary for the veritable ensemble of contractile responses to meet increased hemodynamic demands and disruption of any of these targeted mechanisms may lead to inadequate matching of supply to the higher hemodynamic loads as observed in heart failure patients.

Molecule specific effects of PKA on muscle mechanics and ventricular contractility

cTnI and cMyBP-C phosphorylation correlate with ventricular power output

Unphosphorylated cTnI reversibly decreased isometric force

Unphosphorylated cTnI sped rates of force development (ktr)

MyBP-C phosphorylation sped loading shortening and increased power output

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant (R01-HL-57852) to K.S.M. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Brandon J. Biesiadecki for providing recombinant Tn complex used for the striated muscle cell mechanical experiments in this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adhikari BB, Regnier M, Rivera AJ, Kreutziger KL, Martyn DA. Cardiac length dependence of force and force redevelopment kinetics with altered cross-bridge cycling. Biophysical Journal. 2004;87:1784–1794. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.039131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen DG, Kentish JC. The cellular basis of the length-tension relation in cardiac muscle. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1985;17:821–840. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation--contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bristow M, Ginsburg R, Minobe W, Cubicciotti R, Sageman W, Billingham M, Harrison D, Stinson E. Decrease catecholamine sensitivity and beta-adrenergic-receptor density in failing human hearts. New England Journal of Medicine. 1982;307:205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bristow MR. Treatment of chronic heart failure with beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists: convergence of receptor pharmacology and clinical cardiology. Circulation Research. 2011;109:1176–1194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.245092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell K. Rate constant of muscle force redevelopment reflects cooperative activation as well as cross-bridge kinetics. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:254–262. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78664-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colson BA, Bekyarova T, Locher MR, Fitzsimons DP, Irving TC, Moss RL. Protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C increases proximity of myosin heads to actin in resting myocardium. Circulation Research. 2008;103 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colson BA, Patel JR, Chen PP, Bekyarova T, Abdalla MI, Tong CW, Fitzsimons DP, Irving TC, Moss RL. Myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation is the principal mediator of protein kinase A effects on thick filament structure in myocardium. Journal of Molecular & Cellular Cardiology. 2012;53:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Tombe PP, Mateja RD, Tachampa K, Ait Mou Y, Farman GP, Irving TC. Myofilament length dependent activation. Journal of Molecular & Cellular Cardiology. 2011;48:851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Tombe PP, Stienen GJM. Protein kinase A does not alter economy of force maintenance in skinned rat cardiac trabeculae. Circulation Research. 1995;76:734–741. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.5.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edes IF, Czuriga D, Csanyi G, Chlopicki S, Recchia FA, Borbely A, Galajda Z, Edes I, van der Velden J, Stienen GJM, Papp Z. The rate of tension redevelopment is not modulated by sarcomere length in permeabilized human, murine and porcine cardiomyocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 2007 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00537.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endoh M, Blinks JR. Actions of sympathomimetic amines on the Ca2+ transients and contractions of rabbit myocardium: reciprocal changes in myofibrillar responsiveness to Ca2+ mediated through - and β-adrenoceptors. Circulation Research. 1988;62:247–265. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.England PJ. Correlation between contraction and phosphorylation of the inhibitory subunit of troponin in perfused rat heart. FEBS Letters. 1975;50:57–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)81040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.England PJ. Studies on the phosphorylation of the inhibitory subunit of troponin during modification of contraction in perfused rat heart. Biochemical Journal. 1976;160:295–304. doi: 10.1042/bj1600295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabiato A. Computer programs for calculating total from specified free or free from specified total ionic concentrations in aqueous solutions containing multiple metals and ligands. Methods of Enzymology. 1988;157:378–417. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fentze RC, Buck SH, Patel JR, Lin H, Wolska BM, Stojanovic MO, Martin AF, Solaro RJ, Moss RL, Leiden JM. Impaired cardiomyocyte relaxation and diastolic function in transgenic mice expressing slow skeletal troponin I in the heart. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0143z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzsimons DP, Patel JR, Moss RL. Cross-bridge interaction kinetics in rat myocardium are accelerated by strong binding of myosin to the thin filament. Journal of Physiology. 2001;530:263–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0263l.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs F, Martyn DA. Length-dependent Ca2+ activation in cardiac muscle: some remaining questions. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 2005;26:199–212. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garvey JL, Kranias EG, Solaro RJ. Phosphorylation of C protein, troponin-I, and phospholamban in isolated rabbit hearts. Biochemical Journal. 1988;249:709–714. doi: 10.1042/bj2490709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gautel M, Zuffardi O, Freiburg A, Labeit S. Phosphorylation swithches specific for the cardiac isoform of myosin binding protein C: a modulator of cardiac contraction? EMBO Journal. 1995;14:1952–1960. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillis TE, Martyn DA, Rivera AJ, Regnier M. Investigation of thin filament near-neighbor regulatory unit interactions during force development in skinned cardiac and skeletal muscle. Journal of Physiology. 2007;580:561–576. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gresham KS, Mamidi R, Stelzer JE. The contribution of cardiac myosin binding protein-C ser282 phosphorylation to the rate of force generation and in vivo cardiac contractility. Journal of Physiology. 2014;592:3747–3765. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.276022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruen M, Prinz H, Gautel M. cAPK-phosphorylation controls the interaction of the regulatory domain of cardiac myosin binding C with myosin-S2 in an on-off fashion. FEBS Letters. 1999;453:254–259. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00727-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanft LM, Biesiadecki BJ, McDonald KS. Length dependence of striated muscle force generation is controlled by phosphorylation of cTnI at serines 23/24. Journal of Physiology. 2013;591:4535–4547. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.258400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanft LM, Greaser ML, McDonald KS. Titin-mediated control of cardiac myofibrillar function. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2014;552–553:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanft LM, McDonald KS. Length dependence of force generation exhibit similarities between rat cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 2010;588:2891–2903. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.190504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanft LM, McDonald KS. Sarcomere length dependence of power output is increased after PKA treatment in rat cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;296:H1524–H1531. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00864.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartzell HC. Phosphorylation of C-protein in intact amphibian cardiac muscle: correlation between 32P incorporation and twitch relaxation. Journal of General Physiology. 1984;83:563–588. doi: 10.1085/jgp.83.4.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartzell HC, Titus L. Effects of cholinergic and adrenergic agonists on phosphorylation of a 165,000-dalton myofibrillar protein in intact cardiac muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982;257:2111–2120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herron TJ, Korte FS, McDonald KS. Power output is increased after phosphorylation of myofibrillar proteins in rat skinned cardiac myocytes. Circulation Research. 2001;89:1184–1190. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill AV. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1938;126:136–195. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinken AC, McDonald KS. Inorganic phosphate speeds loaded shortening in rat skinned cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 2004;287:C500–C507. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00049.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann PA, Lange JH., III Effects of phosphorylation of troponin I and C protein on isometric tension and velocity of unloaded shortening in skinned single cardiac myocytes from rats. Circulation Research. 1994;74:718–726. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holroyde MJ, Howe E, Solaro RJ. Modification of calcium requirements for activation of cardiac myofibrillar ATPase by cAMP dependent phosphorylation. Biochemica Biophysica ACTA. 1979;586:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janssen PML, De Tombe PP. Protein kinase A does not alter unloaded velocity of sarcomere shortening in skinned rat cardiac trabeculae. American Journal of Physiology (Heart Circ Physiol) 1997;42:H2415–H2422. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeacocke SA, England PJ. Phosphorylation of a myofibrillar protein of Mr 150,000 in perfused rat heart, and the tentative identification of this as C-protein. FEBS Letters. 1980;122:129–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi T, Solaro RJ. Increased Ca2 affinity of cardiac thin filaments reconstituted with cardiomyopathy-related mutant cardiac troponin I. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:13471–13477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korte FS, Herron TJ, Rovetto MJ, McDonald KS. Power output is linearly related to MyHC content in rat skinned myocytes and isolated working hearts. American Journal of Physiology. 2005;289:H801–812. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01227.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korte FS, McDonald KS. Sarcomere length dependence of rat skinned cardiac myocyte mechanical properties: dependence on myosin heavy chain. Journal of Physiology. 2007;581:725–739. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korte FS, McDonald KS, Harris SP, Moss RL. Loaded shortening, power output, and rate of force redevelopment are increased with knockout of cardiac myosin binding protein-C. Circulation Research. 2003;93:752–758. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000096363.85588.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunst G, Kress KR, Gruen M, Uttenweiler D, Gautel M, Fink RHA. Myosin binding protein C, a phosphorylation-dependent force regulator in muscle that controls the attachment of myosin heads by its interaction with myosin S2. Circulation Research. 2000;86:51–58. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luther PK. Direct visualization of myosin-binding protein C bridging myosin and actin filaments in intact muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2011;108:11423–11428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103216108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDonald KS. Ca2+ dependence of loaded shortening in rat skinned cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle fibers. Journal of Physiology. 2000;525:169–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonald KS. The interdependence of calcium activation, sarcomere length, and power output in the heart. Pflugers Archives. 2011;462:61–67. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0949-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonald KS, Hanft LM, Domeier TL, Emter CA. Length and PKA dependence of force generation and loaded shortening in porcine cardiac myocytes. Biochemistry Research International. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/371415. Epub 2012 Jul 5, 371415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonald KS, Wolff MR, Moss RL. Force-velocity and power-load curves in rat skinned cardiac myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1998:519–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.519bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Messer AE, Jacques AM, Marston SB. Troponin phosphorylation and regulatory function in human heart muscle: dephosphorylation of Ser 23/24 on troponin I could account for the contractile defect in end-stage heart failure. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2007;42:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milani-Nejad N, Xu J, Davis JP, Campbell KS, Janssen PM. Effect of muscle length on cross-bridge kinetics in intact cardiac trabeculae at body temperature. Journal of General Physiology. 2013;141:133–139. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mun JY, Gulick J, Robbins J, Woodhead J, Lehman W, Craig R. Electron microscopy and 3D reconstruction of F-actin decorated with cardiac myosin-binding C (cMyBP-C) Journal of Molecular Biology. 2011;410:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nixon BR, Liu B, Scellini B, Tesi C, Piroddi N, Ogut O, Solaro RJ, Ziolo MT, Janssen PM, Davis JP, Poggesi C, Biesiadecki BJ. Tropomyosin Ser-283 pseudo-phosphorylation slows myofibril relaxation. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.11.010. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nixon BR, Thawornkaiwong A, Jin J, Brundage EA, Little SC, Davis JP, Solaro RJ, Biesiadecki BJ. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates cardiac troponin I at Ser-150 to increase myofilament calcium sensitivity and blunt PKA-dependent function. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:19136–19147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.323048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel JR, Pleitner JM, Moss RL, Greaser ML. Magnitude of length-dependent changes in contractile properties varies with titin isoform in rat ventricles. American Journal of Physiology. 2012;302:H697–H708. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00800.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Previs MJ, Beck Previs S, Gulick J, Robbins J, Warshaw DM. Molecular mechanics of cardiac myosin-binding protein C in native thick filaments. Science. 2012;337:1215–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.1223602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rao V, YC, Lindert S, Wang D, Oxenford L, McCulloch AD, McCammon JA, Regnier M. PKA phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I modulates activation and relaxation kinetics of ventricular myofibrils. Biophysical Journal. 2014;107:1196–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Regnier M, Martin H, Barsotti RJ, Rivera AJ, Martyn DA, Clemmons E. Cross-bridge versus thin filament contributions to the level and rate of force development in cardiac muscle. Biophysical Journal. 2004;87:1815–1824. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.039123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robertson SP, Johnson JD, Holroyde MJ, Kranias EG, Potter JD, Solaro RJ. The effect of troponin I phosphorylation on the Ca2+-binding properties of the Ca2+-regulatory site of bovine cardiac troponin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982;257:260–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rovetto MJ. Mechanical function and metabolism of working rat hearts perfused with the negative chronotropic agent mixidine fumarate. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1980;164:13–17. doi: 10.3181/00379727-164-40816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sadayappan S, de Tombe PP. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C: redefining its structure and function. Biophysical Reviews. 2012;4:93–106. doi: 10.1007/s12551-012-0067-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shaffer JF, Kensler RW, Harris SP. The myosin-binding protein C motif binds to F-actin in a phosphorylation-sensitive manner. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:12318–12327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808850200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Solaro RJ, Henze M, Kobayashi T. Integration of troponin I phosphorylation with cardiac regulatory networks. Circulation Research. 2013;112:355–366. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Solaro RJ, Moir AJG, Perry SV. Phosphorylation of troponin I and the inotropic effect of adrenaline in the perfused rabbit heart. Nature. 1976;262:615–616. doi: 10.1038/262615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Moss RL. Protein Kinase A-Mediated Acceleration of the Stretch Activation Response in Murine Skinned Myocardium Is Eliminated by Ablation of cMyBP-C. Circulation Research. 2006;99:884–890. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000245191.34690.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Strang KT, Sweitzer NK, Greaser ML, Moss RL. Beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation increases unloaded shortening velocity of skinned single ventricular myocytes from rats. Circulation Research. 1994;74:542–549. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tardiff JC. Thin filament mutations: developing an integrative approach to a complex disorder. Circulation Research. 2011;108:765–782. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van der Velden J, Papp Z, Zaremba R, Boontje NM, de Jong JW, Owen VJ, Burton PB, Goldmann P, Jaquet K, Stienen GJM. Increased calcium sensitivity of the contractile apparatus in end-stage human heart failure results from altered phosphorylation of contractile proteins. Cardiovascular Research. 2003;57:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vannier C, Chevassus H, Vassort G. Ca-dependence of isometric kinetics in single skinned ventricular cardiomyocytes from rats. Cardiovascular Research. 1996;32:580–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wattanapermpool J, Guo X, Solaro RJ. The unique amino-terminal peptide of cardiac troponin I regulates myofibrillar activity only when it is phosphorylated. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1995;27:1383–1391. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1995.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Whitten AE, Jeffries CM, Harris SP, Trewhella J. Cardiac myosin-binding C decorates F-actin: implications for cardiac function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2008;105:18360–18365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808903105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolff MR, Buck SH, Stoker SW, Greaser ML, Mentzer RM. Myofibrillar calcium sensitivities of isometric tension is increased in human dilated cardomyopathies. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;98:167–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI118762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wolff MR, McDonald KS, Moss RL. Rate of tension development in cardiac muscle varies with level of activator calcium. Circulation Research. 1995;76:154–160. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamasaki R, Wu Y, McNabb M, Greaser ML, Labeit D, Granzier H. Protein kinase A phosphorylates titin's cardiac-specific N2B domain and reduces passive tension in rat cardiac myocytes. Circulation Research. 2002;90:1181–1188. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000021115.24712.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang P, Kirk JA, Ji W, dos Remedios CG, Kass DA, Van Eyk JE, Murphy AM. Multiple reaction monitoring to identify site-specific troponin I phosphorylated residues in the failing human heart. Circulation. 2012;126:1828–1837. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]