Abstract

Background

Measles is a highly infectious illness requiring herd immunity of 95% to interrupt transmission. Measles is targeted for elimination in China, which has not reached elimination goals despite high vaccination coverage. We developed a population profile of measles immunity among residents aged 0 through 49 years in Tianjin, China.

Methods

Participants were either from community population registers or community immunization records. Measles IgG antibody status was assessed using dried blood spots. We examined the association between measles IgG antibody status and independent variables including urbanicity, sex, vaccination, measles history, and age.

Results

2,818 people were enrolled. The proportion measles IgG negative increased from 50.7% for infants aged 1 month to 98.3% for those aged 7 months. After 8 months, the age of vaccination eligibility, the proportion of infants and children measles IgG negative decreased. Overall, 7.8% of participants 9 months of age or older lacked measles immunity including over 10% of those 20–39 years. Age and vaccination status were significantly associated with measles IgG status in the multivariable model. The odds of positive IgG status were 0.337 times as high for unvaccinated compared to vaccinated (95% CI: 0.217, 0.524).

Conclusions

The proportion of persons in Tianjin, China immune to measles was lower than herd immunity threshold with less than 90% of people aged 20–39 years demonstrating protection. Immunization programs in Tianjin have been successful in vaccinating younger age groups although high immunization coverage in infants and children alone won’t provide protective herd immunity, given the large proportion of non-immune adults.

Keywords: Measles, China, Seroprevalence, Disease Elimination, Immunization Programs, Epidemiologic Surveillance

Introduction

Measles has historically been a major cause of infectious childhood morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Over the last twenty-five years, however, childhood deaths from measles globally have decreased dramatically, from 631,200 in 1990 to 145,700 in 2013, in part due to an increased international focus on global eradication [2,3]. Measles has now been successfully eliminated in the Americas [4]. The other five WHO regions have also set a target for elimination by 2020 including China in the Pan Western Pacific Region [5,6]. Although China had originally established a national goal of elimination by 2012, the target was not met and the country instead has recently experienced year-on-year increases in the number of measles cases in 2013 and 2014 [7].

Measles is a highly communicable disease and at least 94% of the population needs to be immune to interrupt endemic transmission of disease [8]. Both active and passive immunity play important roles in protecting against measles. Following infection with the virus, an individual acquires both cellular and humoral immunity with the latter detectable by the presence of measles IgG antibodies in the serum which persist for decades [9]. Immunization with a live measles-containing vaccine (MCV) elicits an immune response similar to natural disease and both are forms of active immunity. Passive immunity results from transplacental transfer of measles antibody from mother to child generally during the third trimester of pregnancy [10]. Whether mother’s immunity is derived from natural disease or immunization, the neonate’s passive immunity from maternal antibodies theoretically protects against measles for several months after birth. The duration of protection depends on the quantity of antibody transferred and the rate of antibody decay in the infant [11]. Antibodies present from passive immunity may interfere with an active immune response and it is recommended that vaccines be given after maternal antibodies have waned.

The recommended age for administration of the first dose of MCV falls between 8 to 12 months but varies by country. The timing of the initial dose represents a trade-off between providing the vaccine early enough to prevent acquisition of disease, the age-dependent risk of which differs across countries, balanced against the potential for interference of the infant’s immune response by maternal antibodies [12,13]. Moreover, young infants (i.e., aged ≤6 months) develop less of a humoral response to measles vaccination than older infants, no matter the mother’s immune status [14].

In China, routine measles vaccination has been available for children as young as 8 months since 1966 [15]. However, the vaccine was not widely administered until 1978 when it was incorporated into the expanded program on immunization (EPI) and provided for free to all children. A second dose of MCV was added to China’s EPI in 1986 with a recommendation for administration at age 7 years which was subsequently changed to age 18–24 months in 2005 [16]. Some regions of China, including the Tianjin Municipality, provide an additional third dose at age 5 years. Since 2004, most Chinese provinces have conducted at least two supplementary immunization activities (SIAs), which have targeted all children age 8 months through 14 years, regardless of their previous vaccination status, in an effort to reduce transmission of measles [7,17].

China has had notable success in controlling measles since the introduction of the vaccine. Although it has an annual birth cohort of roughly 16 million children, the second largest in the world, vaccination coverage among children is generally high and at a level that exceeds herd immunity thresholds [18,19]. Measles vaccines are provided free to both local residents and to internal migrants who relocate from rural to urban areas with SIAs reaching the majority of both local and migrant children [20]. Moreover, in most areas in China, governmental public health authority now has access to comprehensive notifiable disease surveillance systems and immunization information systems to monitor measles cases, detect outbreaks, and assess vaccine uptake [7]. Tianjin, located approximately 110 kilometers southeast of Beijing in the northern part of the country, is one of the most populous municipalities in China and serves as an important center of trade and economics. In 2014, 14.7 million people lived in Tianjin’s 16 districts, which span from urban and suburban to rural areas. The dense population of urban districts reside in historical business areas, whereas suburban districts and rural counties are more industrial and have less access to public services [21,22]. Below the district/county level, residents are registered to live in either a rural village or an urban community, with a total of 5,073 villages/communities throughout the municipality. In Tianjin, the municipal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is responsible for serving the entire municipality and directs staff at district and local CDCs who carry out much of the work in investigating outbreaks and evaluating immunization programs.

Given the challenges in the control of measles in China, assessing population susceptibility is an important step in developing a better understanding of the epidemiology of measles and in advancing an effective elimination strategy. Using information from a population-based study of measles immunity in combination with case data from China’s public health surveillance system, we developed a population profile of measles immunity among residents aged 0 through 49 years in Tianjin, and compared this profile to the distribution of measles cases across different age groups. We anticipate that measles immunity will be low in both infants and adults between 20 and 40 years since cases predominantly occur in these two age groups [23].

Methods

The targeted sample size consisted of 2800 individuals aged 0–49 years, with 200 individuals in each age category (groups of 3 month blocks for infants <1 year of age, and 10-year age blocks, thereafter). This sample size would allow us to generate age-stratified confidence intervals of <14%, which is sufficient to compare measles immunity across age groups given immunity levels reported in previous literature [24]. Women aged 20–39 were oversampled in order to generate more precise confidence intervals and because we concomitantly enrolled mothers of every infant <1 year of age. The study enrolled participants between November 2011 and April 2015 using a two-stage cluster sample design. In the first stage, 120 villages/communities were selected through a probability proportionate to size procedure while insuring that each district was represented by at least one village/community. In the second stage, which was conducted within each village/community, 12 to 32 people aged 1–49 years from the village’s population registry were selected using an age-stratified random selection procedure. The enrollment age cutoff date was selected to be age 49 years old to correspond with introduction of the measles vaccine in China in 1966 [25]. Because of a systematic delay in listing infants in the village/community registry, infants age <1 year were selected from records housed at local immunization clinics. An age-stratified random sample of infants was drawn from the clinic list although the number of infants from each village/community varied because some small rural villages had relatively few infants. The mother of each infant was also enrolled in the study.

Prior to data collection, informed consent was obtained from adult participants and the parents of minors enrolled in the study were required to give their consent for the minor’s participation. Study enrollees completed an in-person interview administered by Tianjin CDC staff that required approximately 10 minutes to complete; parents or guardians were included in the interview for any participant <18 years of age. The interview included questions about socio-demographic characteristics, vaccination history, measles infection history, and exposure to congregate settings. Five bloodspots from the participant’s finger were collected using a single-use lancet, dropped onto filter paper, and dried. After transport to the Tianjin CDC laboratory, dried bloodspots were tested for measles IgG antibodies [26]. Measles IgG testing was conducted using SERION ELISA classic measles IgG (quantitative) Institut Virion/Serion GmbH, Würzberg, Germany. The laboratory results were interpreted according to the guidelines from the Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China [27]. Threshold levels for IgG antibody test results were > 200 IU/ml for positive, 150 to 200 IU/ml for borderline, and <150 IU/ml for negative.

Each village/community was classified as either urban, suburban or rural based on which of the 16 districts it was located in; the urban districts included Heping, Hedong, Hexi, Nankai, Hebei, Hongqiao, and Binhai New Area; suburban districts were Jinnan, Dongli, Xiqing, and Beichen; and rural districts comprised Baodi, Wuqing, Ji, Jinghai, and Ninghe.

We compared the seroprevalence data to measles cases recorded in the national notifiable disease registry, the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (CISDCP). From this source, we tabulated the age of all 12,466 measles case-patients reported from 2005 through 2014 in Tianjin.

Statistical analysis

To develop a population profile of measles immunity, measles IgG status was compared by socio-demographic characteristics using basic descriptive statistics, including counts, frequencies and proportions. For the multivariable logistic regression model, we examined the association between a dichotomous measles IgG antibody status (positive vs. borderline/negative) and several independent variables including urbanicity, sex, vaccination history, measles history, and age. Urbanicity was determined to not be a statistically significant predictor of measles IgG antibody status and was therefore removed from the final model. An ordinal logistic regression model, with three outcomes (positive, borderline, and negative measles IgG antibody status) and the same predictor variables, was also tested and yielded substantively similar results and was thus discarded in favor of the simplest final model. Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values were reported from the final model.

The data management for the study was performed using the OpenClinica database system version 3.3 (OpenClinica LLC, Waltham, MA, USA). Data analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The population-based measles immunity study was approved by both the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Tianjin Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ethics Committee. The study received approval to not obtain assent from minors as it is not customary in China for children to give assent when parental permission has been granted. Public health surveillance data from CISDCP were collected for disease control purposes and were provided for use in this paper without individual identifiers and were, therefore, deemed exempt from regulatory review by the University of Michigan IRB.

Results

A total of 2,818 individuals comprising 1,200 persons aged 1 through 49 years, in addition to 809 mother-infant pairs (1,618 individuals), were included. There were 173 people who declined to participate, and according to protocol, replacements from their communities were found to maintain a sample size of 2,818. Most participants (2,050, 72.7%) participants tested positive for measles IgG, 72 (2.6%) tested as borderline and 696 (24.7%) were negative. Results among the 2,213 participants who were ≥9 months of age showed 1,942 (87.8%) as measles IgG antibody positive; seropositivity was comparable between males and females, and also by urbanicity, mother’s education level, and participant education level for those >18 years (Table 1). Participants who received at least one dose of MCV were more likely to be antibody positive (92.7%) compared to those who had not received any doses of MCV (83.0%). Similarly, 91.9% of participants who reported that they had been diagnosed with measles were measles IgG antibody positive versus 87.5% of those who reported no prior measles.

Table 1.

Measles IgG antibody status among study participants ≥9 months of age, Tianjin, China, 2011–2015 (n=2213)

| Percent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Positive | Negative | Borderline | ||

| Overall | 2213 | 87.8 | 10.0 | 2.3 | |

| Sex | Female | 1616 | 87.4 | 10.2 | 2.4 |

| Male | 597 | 88.8 | 9.4 | 1.8 | |

| District Type | Rural | 707 | 89.5 | 8.5 | 2.0 |

| Suburban | 383 | 86.2 | 11.5 | 2.4 | |

| Urban | 1123 | 87.2 | 10.4 | 2.4 | |

| Measles Vaccination Status | No | 276 | 83.0 | 14.9 | 2.2 |

| Yes | 794 | 92.7 | 5.2 | 2.1 | |

| Unknown | 1142 | 85.5 | 12.2 | 2.4 | |

| History of Measles Disease | No | 1980 | 87.5 | 10.2 | 2.3 |

| Yes | 110 | 91.8 | 7.3 | 0.9 | |

| Unknown | 123 | 88.6 | 8.9 | 2.4 | |

| Mother’s Education | Primary School | 574 | 86.1 | 11.2 | 2.8 |

| Middle School | 702 | 87.3 | 10.5 | 2.1 | |

| High School | 332 | 88.9 | 8.7 | 2.4 | |

| Vocational | 253 | 87.8 | 9.9 | 2.4 | |

| College/University or higher | 178 | 93.3 | 4.5 | 2.3 | |

| None/Unknown | 174 | 87.4 | 12.1 | 0.6 | |

| Participant’s Education Level (>=18 years of age) | Primary School | 73 | 87.7 | 6.9 | 5.5 |

| Middle School | 492 | 85.4 | 12.8 | 1.8 | |

| High School | 189 | 86.8 | 11.1 | 2.1 | |

| Vocational | 422 | 86.3 | 11.4 | 2.4 | |

| College/University or higher | 429 | 84.9 | 12.6 | 2.6 | |

| None | 25 | 88.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | |

Antibody status, vaccination status, and history of measles disease varied by age (Table 2). A significant majority of children had received at least one dose of MCV among children 9–11 months of age (97.6%) and 1–9 years of age (98.5%) while older children, adolescents, and adults generally had much lower proportions of vaccinated. Among participants age 10 years and older, the proportion who had an unknown vaccination status increased with greater age. Among participants age 20–39, approximately 70% were unsure whether they had received a dose of MCV. With increasing age of participants, there also was a comparable increase in the proportion of individuals among each successive age group who did not know their personal measles disease history, ranging from <2% of those <20 years to 12.0% of adults aged 40–49 years.

Table 2.

Measles sero-status, vaccination history, and disease history by age group, Tianjin, China, 2011–2015.

| IgG Status | Vaccination Status | Disease History | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | % Positive | % Yes | % Unknown | % Yes | % Unknown | |

| <9 Months | 605 | 17.9 | 8.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 9–12 Months | 204 | 94.6 | 97.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| 1–9 Years | 200 | 97.5 | 98.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| 10–19 Years | 213 | 89.2 | 73.2 | 25.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| 20–29 Years | 827 | 86.2 | 16.0 | 69.8 | 5.3 | 5.6 |

| 30–39 Years | 560 | 81.3 | 14.5 | 69.1 | 6.3 | 8.2 |

| 40–49 Years | 209 | 93.8 | 13.9 | 58.9 | 12.0 | 12.0 |

| Total | 2818 | 72.7 | 30.1 | 40.6 | 3.9 | 4.4 |

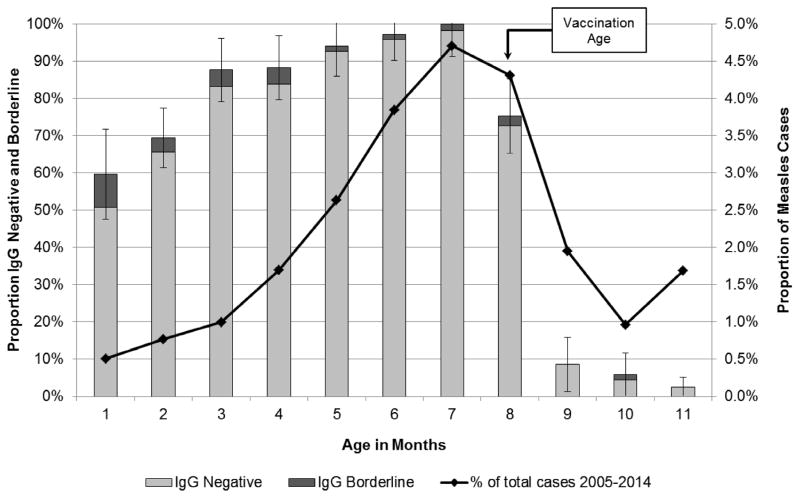

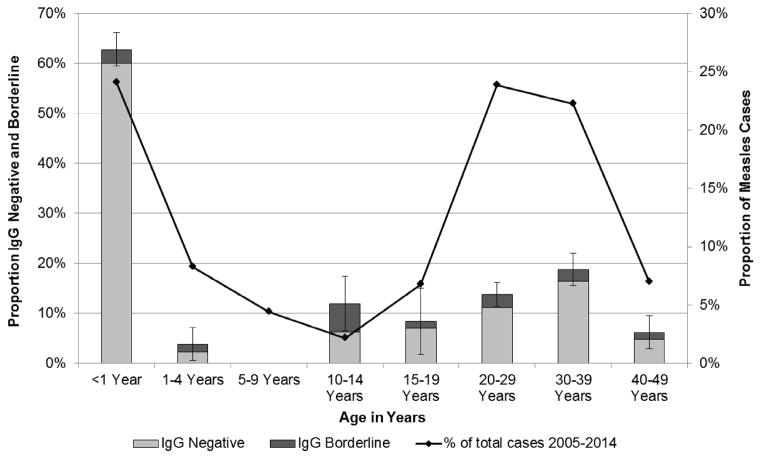

The proportion of infants (i.e. <12 months of age) who tested measles IgG antibody negative increased from 50.7% for those aged 1 month to 98.3% for participants aged 7 months (Figure 1). After vaccination age (i.e. 8 months), the proportion of infants and children who were measles IgG antibody negative sharply decreased (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Only 1.5% of children aged 1–9 years were IgG negative. Among study participants over 10 years of age, a progressively increasing proportion had no evidence of immunity against measles, including 6% of those aged 10–14 years, 7% of those aged 15–19 years, 11% of those aged 20–29 years, and 16% of those aged 30–39 years (Figure 2). The age distribution of measles cases in Tianjin followed a U-shaped curve and was highest for those at 7 months and again at 20–39 years which correlated closely with the age distribution of measles susceptibility t based on IgG antibody status (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Measles IgG antibody status and measles cases among infants age 0 to <12 months, Tianjin, China, 2011–2015

Figure 2.

Measles IgG antibody status and measles cases among all participants, Tianjin, China, 2011–2015

We also examined measles immunity by birth cohort. For those born before measles vaccination started in 1966, 97.6% (40/41) were measles IgG positive. The percent positive by years of birth were: 88.5% (291/329) of people born during1966–1977 when measles vaccine was introduced in China; 83.6% (560/670) of people born 1978–1985 when measles vaccine was added to the EPI; 86.3% (669/775) of people born 1986–2004 when a second dose of measles vaccine was added; and, 96.9% (154/159) of people over 18 months born since 2005, when the recommendation for administration of the second dose was adjusted from 7 years to age 18–24 months.

The multivariable model (Table 3), shows a declining trend of positive antibody status in older infants compared to younger infants, which once again increases after they reach the age of recommended vaccination (Table 3). Compared to infants age 9 to 11 months, infants aged 0 to 2 months had 0.082 times the odds of having immunity against measles (95% CI: 0.037, 0.180), and infants 6 to 8 months had 0.012 times the odds of measles IgG antibody positivity (95% CI: 0.005, 0.026). When comparing participants between the ages of 9–11 months with all other older age groups up to age 29 years, there was not a statistically significant difference in measles IgG antibody status. In contrast, adults 30–39 years, had markedly lower odds of being measles IgG antibody positive compared to infants 9 to 11 months (OR: 0.385, 95% CI: 0.185, 0.801). Neither sex nor reported history of measles disease was significantly associated with measles IgG antibody status, but vaccination status was. Compared to participants who had at least one dose of MCV, those who received no MCV had 0.337 times the odds of being measles IgG antibody positive (95% CI: 0.217, 0.524). Participants with an unknown vaccination status also had lower odds of being measles IgG antibody positive compared to participants known to have received at least one dose of MCV (OR: 0.541, 95% CI: 0.362, 0.807).

Table 3.

Demographic and other predictors of IgG seopositivity in Tianjin, China (n=2,818); a multivariable logistic regression model.

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 1.266 | 0.975 | 1.645 | 0.0769 |

| Male | ref | ||||

|

| |||||

| Vaccinated | No | 0.337 | 0.217 | 0.524 | <.0001 |

| Unknown | 0.541 | 0.362 | 0.807 | 0.0026 | |

| Yes | ref | ||||

|

| |||||

| Measles History | No | 0.59 | 0.292 | 1.192 | 0.1415 |

| Unknown | 0.768 | 0.315 | 1.871 | 0.5615 | |

| Yes | ref | ||||

|

| |||||

| Age | 0 to <3 Months | 0.082 | 0.037 | 0.18 | <.0001 |

| 3 to <6 Months | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.042 | <.0001 | |

| 6 to <9 Months | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.026 | <.0001 | |

| 9 to <12 Months | ref | ||||

| 1 to 9 Years | 2.134 | 0.727 | 6.264 | 0.1678 | |

| 10 to 19 Years | 0.529 | 0.248 | 1.131 | 0.1006 | |

| 20 to 29 Years | 0.545 | 0.263 | 1.129 | 0.1025 | |

| 30 to 39 Years | 0.385 | 0.185 | 0.801 | 0.0107 | |

| 40 to 49 Years | 1.463 | 0.596 | 3.592 | 0.4066 | |

Discussion

Measles is one of the most highly infectious diseases known to humans [8], and has historically been a major contributor to childhood illness and death globally [1,2]. In this cross-sectional seroprevalence study in Tianjin, China, there were progressively increasing levels of age-related measles susceptibility in infants extending to 8 months, the age of vaccination eligibility, at which point most infants were immune. We also found over 10% of those aged 20–39 years, an age range typically associated with child-bearing and rearing of infants and young children, had no evidence of measles immunity. This bimodal age distribution for peak measles susceptibility in infants and young adults places the former at high risk for disease acquisition and potentially serious illness. Additionally, the lack of measles immunity in infants under 8 months is difficult to address since they are not eligible for vaccination and China has not traditionally focused on immunizing adults.

Theoretically, when more than 95% of a population is immune to measles vis a vis a combination of active) and passive immunity, the basic reproduction number will fall below 1, and endemic transmission will be interrupted [8]. In this population-based study, we found the proportion of people with measles immunity measles in Tianjin was lower than the herd immunity threshold with less than 90% of people aged 10–39 years demonstrating sero-protection against measles. A seroprevalence survey by He et al. in Zhejiang province in 2009 also found that fewer than 90% of adults over 20 years of age were immune to measles, although over 95% of children aged 2–9 years had immunity [28]. Lower levels of measles immunity in adults has obvious relevance for the epidemiology of disease and over half of all measles cases from 2005 through 2014 in Tianjin were in individuals ≥20 years of age [23].

Low measles seropositivity in adults of reproductive age could have major implications for infants since it could result in non-immune parents caring for or otherwise having contact with newborns and infants too young for vaccination. The high vaccination coverage in older infants and young children, and resulting high measles seropositivity, is helpful to control efforts but in terms of transmission is likely mitigated by China’s one-child policy with infants predominantly in contact with parents and grandparents (who may be susceptible), and not older, recently-vaccinated children Importantly, vaccination coverage levels should not be simply equated with population immunity, which previous studies have done [29]. This is particularly true for China, where many adults may not be immune from vaccination given that widespread adoption of a 2-dose vaccination schedule only occurred within the past 3 decades.

We found that with increasing age, neonates rapidly lost measurable antibody protection. The level of transplacental maternal antibodies in infants is a function of a number of key variables including the quantity of antibody in the mother and the efficiency and duration of antibody placental transfer. The rate of catabolic degradation over several months in the young infant is itself related to nutrition and health status [10]. Early literature on measles vaccine effectiveness showed that vaccine efficacy was lower at younger ages due to the presence of maternal antibodies; a review of 70 studies showed vaccine efficacy of 84.0% at 9 to 11 months of age and 92.5% at 12 months of age or older [30]. A more recent study found no statistical difference in the safety or immunological results of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine administered at 8 months versus 12 months [31]. Because antibody load in the mother is itself determined by the nature of the infection, with vaccination resulting in fewer antibodies produced relative to natural infection, it may be that in more recent years characterized by decreases in measles cases, fewer mothers having a history of measles disease. Consequently, these vaccinated mother who have never experienced measles disease, may simply have fewer antibodies to transfer on to their fetus compared to previous generations exposed to endemic measles transmission [32,33].

Our finding that a low proportion of young adults have immunological protection against measles has a significant implication for control efforts in China. Targeting these individuals for vaccination, many of whom are in the peak years for childbearing, could be a key component of a successful strategy to prevent disease in their age group and subsequent transmission to young infants, specifically, and to elimination efforts, generally. Tianjin requires university students to provide evidence of measles vaccination upon starting their educational program, but other institutions and programs frequented or used by young adults could also be targeted for those young people who do not attend college. For example, parents and other family members could be offered the option of measles vaccination at prenatal or postnatal health check-ups for their infants and children however mothers would not be eligible for live measles vaccination at the prenatal appointment. However, it’s important to note that similar programs to cocoon children against pertussis in developed countries have not been particularly successful because of difficulties in vaccinating adults, especially fathers and other adult household contacts other than mothers, during child health check-ups [34]. Another option might be to accelerate SIAs which could target a broad age range of adults; during the measles elimination and post-elimination phase in the Americas, 39 speed-up campaigns were conducted to ensure that countries had adequate levels of measles immunity among adolescents and adults, and these interventions were generally considered important to the overall elimination effort [4]. Other venues for vaccinating young adults could also be considered, expanding the current program of immunizing college matriculants to any older adolescent attending a trade school or training for service industries or other non-traditional venues where young adults could be accessed.

Strengths and limitations

This study is subject to a number of limitations. Measles IgG antibody status was measured by ELISA, and it has been previously demonstrated that several decades after measles infection or vaccination, antibodies may not be measurable even though immunity is present which may lead us to overestimate the number of seronegative individuals in the older age group [35]. Vaccination status and history of measles disease are both subject to recall bias, particularly for older adults. The direction of the bias is not necessarily unidirectional for either vaccination or disease history since participants may not forget an event that actually happened (vaccination or disease), or they may confuse with related events (e.g. rubella infection or vaccination against another disease). The study also had a number of unique strengths. We used a rigorous population-based sampling scheme, which allowed us to enroll residents from diverse villages and communities throughout Tianjin, and we sampled a large age range in order to better quantify the profile of measles immunity. Comparing our results to cases from a robust surveillance system was another notable strength.

Conclusions

The measles control program in Tianjin has generally been successful in attaining high vaccination coverage in its target age group and young, vaccine age-eligible children demonstrate high levels of sero-protection against measles. As China continues its pursuit of an elimination endgame, insuring high immunization coverage in children alone will not be adequate to realizing sufficient levels of population herd immunity, particularly given that a large proportion of adults remain susceptible to measles. China should consider additional strategies to vaccinate adults aged >20 years including speed-up immunization campaigns and implementing mandatory vaccination for all young adults entering a variety of career training venues beyond just university entrance, could be key based on the large proportion of measles cases in that continue to occur in adults, the relatively low proportion of adults who have immune protection from measles, and given the high probability of contact with susceptible infants who are not age-eligible for measles vaccination.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U01-AI-088671). We acknowledge the valuable contributions of Dr. Frances Pouch-Downes, laboratory consultant, and the Tianjin CDC’s laboratory and epidemiology staffs. We are grateful to the citizens of Tianjin who participated in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases [U01-AI-088671].

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mina M, Metcalf C, de Swart RL, Osterhous A, Grenfell B. Long-term measles-induced immunomodulation increases overall childhood infectious disease mortality. Science. 2015;348:694–700. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Measles Fact Sheet. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castillo-Solorzano CC, Matus CR, Flannery B, Marsigli C, Tambini G, Andrus JK. The Americas: paving the road toward global measles eradication. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S270–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Global Measles and Rubella Strategic Plan 2012–2020. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. WHO warns that progress towards eliminating measles has stalled. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma C, Hao L, Zhang Y, Su Q, Rodewald L, An Z, et al. Monitoring progress towards the elimination of measles in China: an analysis of measles surveillance data. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:340–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.130195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine PEM. Herd Immunity: History, Theory, Practice. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:265–302. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidkin I, Jokinen S, Broman M, Leinikki P, Peltola H. Persistence of measles, mumps, and rubella antibodies in an MMR-vaccinated cohort: a 20-year follow-up. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:950–6. doi: 10.1086/528993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmeira P, Quinello C, Silveira-Lessa AL, Zago CA, Carneiro-Sampaio M. IgG placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:985646. doi: 10.1155/2012/985646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leuridan E, Hens N, Hutse V, Ieven M, Aerts M, Van Damme P. Early waning of maternal measles antibodies in era of measles elimination: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2010;340:c1626. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strebel PM, Papania MJ, Fiebelkorn AP, Halsey NA. Measles vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, editors. Vaccines. Elsevier; 2013. pp. 352–87. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orenstein WA, Markowitz L, Preblud SR, Hinman AR, Tomasi A, Bart KJ. Appropriate age for measles vaccination in the United States. Dev Biol Stand. 1986;65:13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar ML, Johnson CE, Chui LW, Whitwell JK, Staehle B, Nalin D. Immune response to measles vaccine in 6-month-old infants of measles seronegative mothers. Vaccine. 1998;16:2047–51. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiang J, Chen Z. Measles Vaccine in the People’s Republic of China. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:506–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng J, Zhou Y, Wang H, Liang X. The role of the China Experts Advisory Committee on Immunization Program. Vaccine. 2010;28S:A84–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma C, An Z, Hao L, Cairns KL, Zhang Y, Ma J, et al. Progress toward measles elimination in the People’s Republic of China, 2000–2009. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S447–54. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montgomery JP, Zhang Y, Carlson B, Ewing S, Wang X, Boulton ML. Measles vaccine coverage and series completion among children 0–8 years of age in Tianjin, China. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:289–95. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ni JD, Xiong YZ, Li T, Yu XN, Qian BQ. Recent Resurgence of Measles in a Community With High Vaccination Coverage. Asia-Pac J Public Health. 2012;XX:1–8. doi: 10.1177/1010539512451852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu X, Xiao S, Chen B, Sa Z. Gaps in the 2010 measles SIA coverage among migrant children in Beijing: Evidence from a parental survey. Vaccine. 2012;30:5721–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Wang Q, Shi W, Deng Z, Wang H. Residential clustering and spatial access to public services in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2015;46:119–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang S, Wang C, Wang M. Synergistic evolution of Shanghai urban economic development transition and social spatial structure. In: Wang MY, Kee P, Gao J, editors. Transform Chinese Cities. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014. pp. 48–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Boulton ML, Montgomery JP, Carlson B, Zhang Y, Gillespie B, et al. The epidemiology of measles in Tianjin, China, 2005–2014. Vaccine. 2015;33:6186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu C, Xu J, Liu W, Zhang W, Wang M, Nie J, et al. Low measles seropositivity rate among children and young adults: A sero-epidemiological study in southern China in 2008. Vaccine. 2010;28:8219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Zeng G, Lee LA, Yang Z, Yu J, Zhou J, et al. Progress in Accelerated Measles Control in the People’s Republic of China, 1991–2000. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:S252–7. doi: 10.1086/368045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downes F, Clark P, Nowak R, Berlin B. Evaluation of dried blood spot specimens for measles antibody determination in outbreak control. Abstr 92nd Gen Meet Am Soc Microbiol; Washington, DC. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China. Diagnostic criteria and principles of management of measles. Beijing, China: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.He H, Chen E, Li Q, Wang Z, Yan R, Fu J, et al. Waning immunity to measles in young adults and booster effects of revaccination in secondary school students. Vaccine. 2013;31:533–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohamud AN, Feleke A, Worku W, Kifle M, Sharma HR. Immunization coverage of 12–23 months old children and associated factors in Jigjiga District, Somali National Regional State, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:865. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uzicanin A, Zimmerman L. Field effectiveness of live attenuated measles-containing vaccines: a review of published literature. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S133–48. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He H, Chen E, Chen H, Wang Z, Li Q, Yan R, et al. Similar immunogenicity of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine administrated at 8 months versus 12 months age in children. Vaccine. 2014;32:4001–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maldonado YA, Lawrence EC, DeHovitz R, Hartzell H, Albrecht P. Early loss of passive measles antibody in infants of mothers with vaccine-induced immunity. Pediatrics. 1995;96:447–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gans HA, Maldonado Ya. Loss of passively acquired maternal antibodies in highly vaccinated populations: an emerging need to define the ontogeny of infant immune responses. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1–3. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amirthalingam G. Strategies to control pertussis in infants. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:552–5. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mossong J, Callaghan CJO, Ratnam S. Modelling antibody response to measles vaccine and subsequent waning of immunity in a low exposure population. Vaccine. 2001;19:523–9. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]