Abstract

Learned food cues can drive feeding in the absence of hunger, and orexin/hypocretin signaling is necessary for this type of overeating. The current study examined whether orexin also mediates cue-food learning during the acquisition and extinction of these associations. In Experiment 1, rats underwent two sessions of Pavlovian appetitive conditioning, consisting of tone-food presentations. Prior to each session, rats received either the orexin 1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 (SB) or vehicle systemically. SB treatment did not affect conditioned responses during the first conditioning session, measured as food cup behavior during the tone and latency to approach the food cup after the tone onset, compared to the vehicle group. During the second conditioning session, SB treatment attenuated learning. All groups that received SB, prior to either the first or second conditioning session, displayed significantly less food cup behavior and had longer latencies to approach the food cup after tone onset compared to the vehicle group. These findings suggest orexin signaling at the 1 receptor mediates the consolidation and recall of cue-food acquisition. In Experiment 2, another group of rats underwent tone-food conditioning sessions (drug free), followed by two extinction sessions under either SB or vehicle treatment. Similar to Experiment 1, SB did not affect conditioned responses during the first session. During the second extinction session, the group that received SB prior to the first extinction session, but vehicle prior to the second, expressed conditioned food cup responses longer after tone offset, when the pellets were previously delivered during conditioning, and maintained shorter latencies to approach the food cup compared to the other groups. The persistence of these conditioned behaviors indicates impairment in extinction consolidation due to SB treatment during the first extinction session. Together, these results demonstrate an important role for orexin signaling during Pavlovian appetitive conditioning and extinction.

Keywords: Conditioning, appetitive, orexin, acquisition, extinction, consolidation

1. Introduction

The motivation to seek and consume food is essential for survival. One neural substrate mediating this motivation is the neuropeptide orexin/hypocretin (for reviews, see [1–3]), which is synthesized within the lateral hypothalamus [4,5], a brain region critical for feeding [6,7]. Specifically, orexin-A is important for appetitive motivation [1] and binds to both orexin receptors, orexin 1 (OX1R) and orexin 2 receptors; however, OX1R has a higher affinity for orexin-A than for orexin-B [5,8]. Indeed, manipulations that disrupt OX1R signaling interfere with the consumption of standard chow [9–11], as well as binge eating for highly palatable foods [12]. OX1R blockade decreases the motivation to work for and seek high fat food [9,13–15], sucrose [16,17], and saccharin [18]. Similarly, orexin knockout mice consume smaller amounts of sucrose [19] and are less motivated to work for food [15]. These studies clearly demonstrate orexin is necessary for the motivation to obtain food.

However, food consumption is not only driven by internal, physiological signals, but can also be induced by external, environmental signals through associative learning. Cues previously associated with food can later increase the motivation to obtain and consume food independent of physiological hunger across species [20–24]. We recently demonstrated that such non-homeostatic, cue-driven consumption also requires orexin signaling [25]. Additionally, orexin neurons are recruited during late Pavlovian cue-food conditioning when cues reliably signal food delivery [26], and by environmental cues previously associated with food [9,27,28]. Nevertheless, whether orexin signaling is necessary during the initial formation of cue-food associations remains unknown.

Here, we used Pavlovian appetitive conditioning to examine if orexin mediates the initial cue-food acquisition and the extinction of these associations. Employing a pharmacological approach, we systemically blocked OX1Rs with the selective antagonist SB-334867 (SB) during the two initial sessions of either acquisition or extinction in two separate experiments. Using a crossover design, we monitored learning in subjects that received either vehicle or SB prior to one or both sessions. This approach allowed assessment of the role of orexin during various phases of learning – the initial acquisition, the consolidation phase, and the recall of the memory. Furthermore, acquisition and extinction are expressed through different behaviors, an increase in responding to a reward and a decrease in responding in the absence of a reward, respectively. Thus, examination of both types of learning allowed for an assessment of orexin signaling function in learning independent of the direction of the behavior and whether the reward was present or not.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Sixty-four, experimentally naïve, male Long-Evans rats (300–325 g) obtained from Charles Rivers Laboratories were used. Rats were individually housed and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 06:00). Behavioral testing was conducted during the light phase between 09:00 and 13:00. Rats were given one week to acclimate to the colony room with ad libitum access to water and food (standard laboratory chow) and were handled and weighed daily. All experiments were in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Boston College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Apparatus

Habituation, acquisition, and extinction occurred in the same set of identical behavioral chambers (30 × 28 × 30 cm; Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA), located in a room different from the colony housing room. Behavioral chambers were composed of an aluminum top and sides with one side containing a recessed food cup (3.2 × 4.2 cm), a transparent Plexiglas front with a hinge, a transparent Plexiglas back, and a black Plexiglas floor, and were illuminated with a house light (4W). Each chamber was contained in an isolation cubicle (79 × 53 × 53 cm; Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) composed of monolithic rigid foam walls, which contained a ventilation fan (55 dB). A video camera located on the rear wall of each isolation cubicle recorded subjects’ behavior during the sessions. The conditioned stimulus (CS) was a 10 s tone (75 dB, 2 kHz), and the unconditioned stimulus (US) was two food pellets (formula 5TUL, 45 mg: Test Diets, Richmond, IN) delivered into the food cup. A computer located in an adjacent room controlled the stimuli and video cameras (GraphicState 3.0, Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA).

2.3. Drugs

SB-334867 (SB; Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO, USA) was suspended in a solution consisting of 2% dimethylsulfoxide and 10% 2-hydroxypropyl-b-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in sterile water. SB was administered via intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) at a volume of 2 ml/kg and concentration of 20 mg/kg. SB or vehicle was given 30 min prior to each acquisition session (Experiment 1) or prior to each extinction session (Experiment 2).

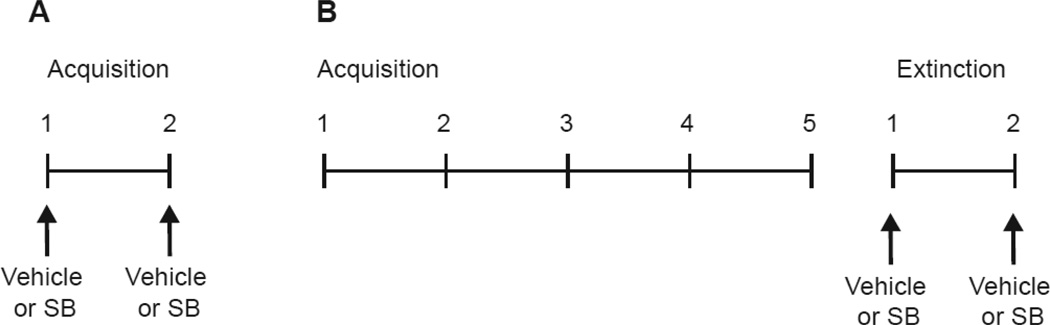

2.4. Experiment 1: Effect of SB on the acquisition of Pavlovian appetitive conditioning

Experimental design is shown in Fig.1A. Rats were food restricted to gradually reach 85% of their ad libitum body weight, which was maintained throughout the experiment. Prior to acquisition, rats were given one 30 min habituation session to acclimate them to the behavioral chambers. During that session all subjects had access to 1 g of the food pellets (US) in the food cup to familiarize them with the pellets.

Figure 1.

Acquisition training commenced the following day. All groups received two identical acquisition sessions on two separate days. During each 34 min session, rats received eight CSUS pairings, where presentations of the CS were immediately followed with delivery of the US. The inter-trial intervals (ITIs) were of variable duration (2–6 min) and were randomly distributed during the sessions. Thirty minutes prior to each session, rats received an injection (i.p.) of either SB or vehicle in a crossover design resulting in four groups: Vehicle/Vehicle (Veh/Veh), Vehicle/SB (Veh/SB), SB/Vehicle (SB/Veh), and SB/SB (n=8/group). The SB/Veh and Veh/SB groups were included to dissociate the impact SB may have on initial learning and consolidation, from memory recall and expression, respectively. The two acquisition sessions were separated by 48 h to eliminate any potential residual drug effects from the first to the second session.

2.5. Experiment 2: Effect of SB on the extinction of Pavlovian appetitive conditioning

Experimental design is shown in Fig.1B. A separate group of rats underwent the same food restriction and habituation session as described above. Rats then underwent five, drug free, acquisition sessions, each consisting of eight CS-US pairings occurring at random ITIs (2–6 min). Following acquisition, rats received two extinction sessions, each with eight CS-only presentations. Thirty minutes prior to each extinction session rats received an injection (i.p.) of either SB or vehicle in a crossover design resulting in the same four groups as described for Experiment 1: Veh/Veh, Veh/SB, SB/Veh, and SB/SB (n=8/group). Extinction sessions occurred 48 h apart to eliminate the possibility of residual drug effects.

2.6. Behavioral Observations

Observations were made from recordings of animals’ behavior during all acquisition and extinction sessions by trained observers unaware of group allocation. The primary measures of learning were expression of food cup behavior and latency to approach the food cup following CS onset. Food cup behavior was defined as standing in front of and directly facing the food cup or displaying distinct nosepokes into the recessed food cup. Observations of animals’ behavior were recorded every 1.25 s during the pre-CS, CS, and post-CS periods. The pre-CS period was the 10 s immediately prior to the onset of the CS, and the post-CS period was the 10 s immediately after the cessation of the CS. The number of food cup responses observed was separately summed for each period (pre-CS, CS, and post-CS), converted to a percentage of total time during each period, and averaged for each trial block (two trials per block) and session, for each group. Latency was the time elapsed from the CS onset until the rat approached the food cup during the 10 s CS and 10 s post-CS. After this time, behavior was considered unspecific to the presentation of the CS, and a maximum latency of 20 s was assigned to any trial in which a response was made later or did not occur. Latency for each CS trial block (two trials per block) and session was averaged for each group. Additionally, to ensure SB did not impact overall arousal, potentially confounding results, rats' behavior was scored every 15 s during the ITIs for sessions with drug treatment. Recorded behaviors included sitting, sniffing, walking, rearing, grooming, and food cup behavior. The number of times each behavior occurred was summed and converted to a percentage of the total number of observations.

2.6. Data analysis

Behavioral data were analyzed using one-way (Session 1 Treatment; first day of acquisition or extinction) or two-way (Session 1 Treatment by Session 2 Treatment; second day of acquisition or extinction) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with CS trial block or pre-CS, CS, and post-CS period as repeated measures where appropriate. Post hoc t-Tests were used for any subsequent analyses. SPSS (v.21) software was used for statistical analyses, and the significance value was set at p <0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: Effect of SB on the acquisition of Pavlovian appetitive conditioning

3.1.1. Acquisition 1

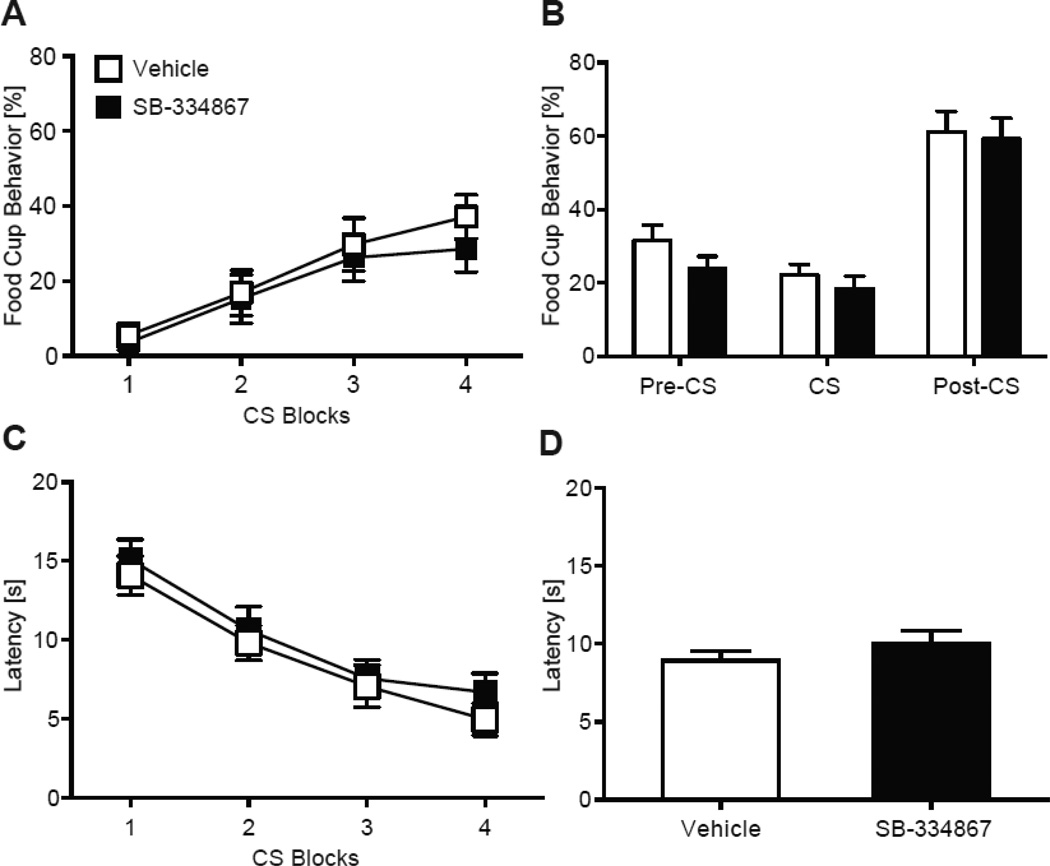

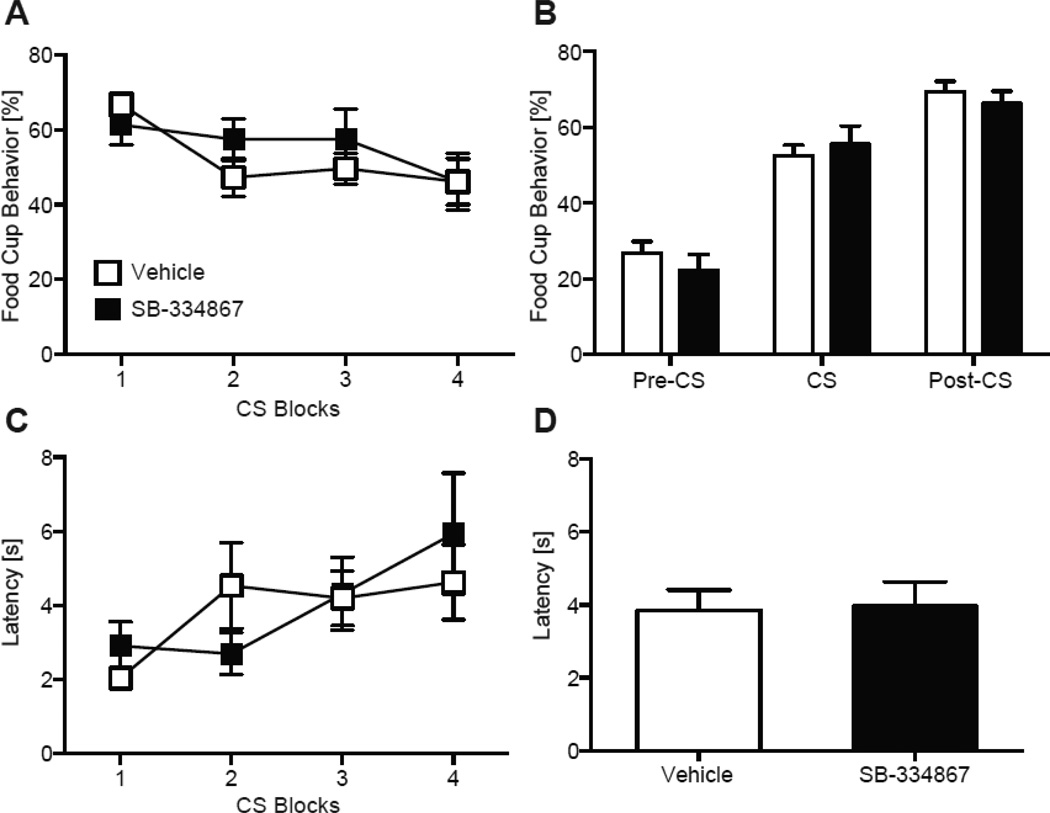

Pretreatment with SB did not alter CS-US learning compared to the vehicle group during the first acquisition session (Fig. 2). All rats increased food cup behavior across CS presentations as the session progressed (Fig. 2A), as shown by a group (SB, Veh) by CS repeated measures ANOVA effect of CS (F (1, 30) = 5.68, p < 0.001). Both groups had similar food cup behavior during the pre-CS, CS, and post-CS periods (ps > 0.05; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Similarly, pretreatment with SB did not affect latency to approach the food cup. Both groups had shorter latencies to the food cup as the session progressed (Fig. 2C), as shown by a group by CS repeated measures ANOVA effect of CS (F (1, 30) = 10.88, p < 0.001). Both groups had similar average latency responding (p > 0.05; Fig. 2D).

Additionally, SB treatment did not affect overall arousal, as there were no differences across any behaviors measured during the ITIs, including sitting, sniffing, walking, rearing, grooming, or food cup behavior compared to the vehicle group (all p values > 0.05; Table 1).

Table 1.

Locomotor behaviors during acquisition sessions. Values represent percentage (mean ± SEM) of all observed behaviors during the inter-trial intervals for SB-334867 (SB) and vehicle (Veh) treated groups.

| Acquisition 1 | Acquisition 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veh | SB | Veh/Veh | Veh/SB | SB/Veh | SB/SB | |

| Sitting | 10.16±1.9 | 12.86±3.0 | 15.17±3.9 | 19.08±2.9 | 13.01±4.1 | 14.48±5.4 |

| Sniffing | 21.13±1.5 | 23.17±2.2 | 14.77±1.3 | 22.19±4.5 | 17.66±2.1 | 19.78±3.2 |

| Walking | 16.16±1.8 | 18.10±1.8 | 16.72±3.3 | 11.67±1.5 | 19.59±3.3 | 17.83±2.9 |

| Rearing | 9.55±1.1 | 10.30±1.3 | 10.13±2.1 | 7.24±1.0* | 12.61±2.4 | 13.47±2.6* |

| Grooming | 5.37±0.7 | 4.12±0.7 | 2.77±0.4 | 4.58±1.1 | 1.89±0.4 | 4.30±1.8 |

| Food Cup | 36.46±2.6 | 29.98±2.9 | 39.25±2.6 | 34.50±6.0 | 33.76±4.5 | 28.68±3.3 |

p<0.05 between groups

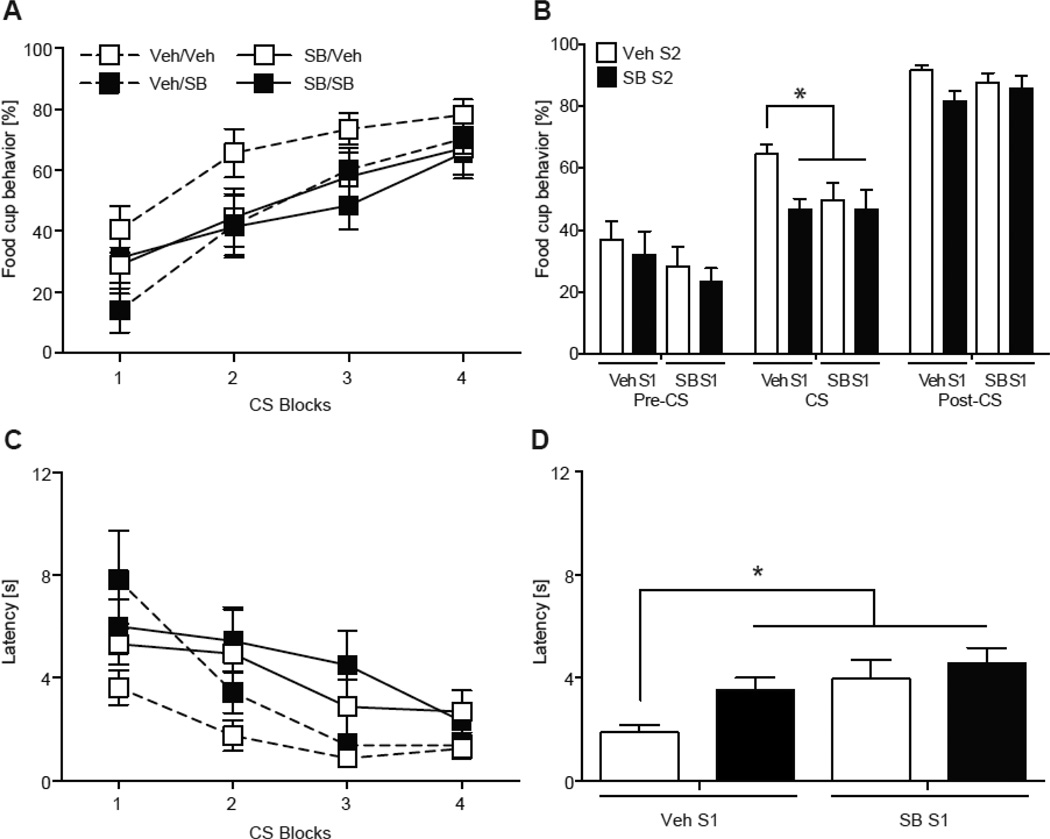

3.1.2. Acquisition 2

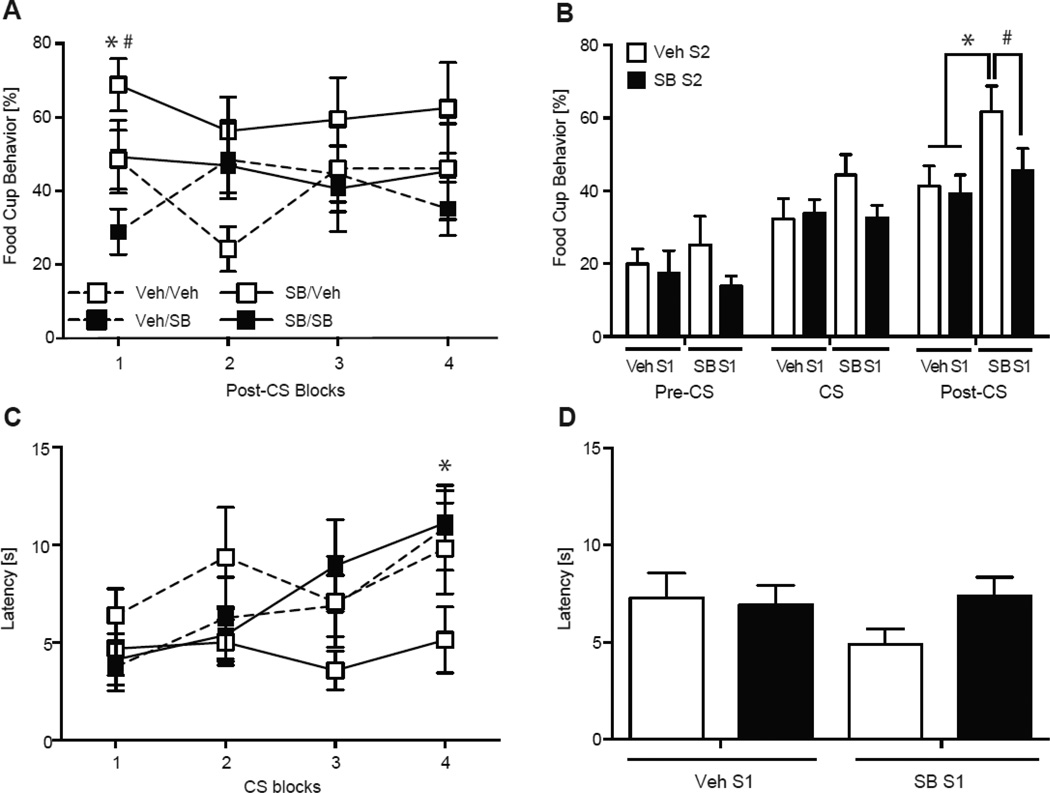

SB treatment affected conditioned responses during the second session of acquisition. All groups increased food cup responding during each CS across the session (Fig. 3A). An increase in responding to the CS was confirmed with a significant CS effect in a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (F (3, 28) = 12.33, p < 0.001; Fig 3A). However, all groups treated with SB had significantly attenuated food cup behavior compared to the Veh/Veh group, specifically during the CS (Fig. 3B). The ANOVA found a main effect of Acquisition 2 Treatment (F (3, 28) = 4.76, p < 0.05), but no effect for Acquisition 1 Treatment or interaction (ps > 0.05). Post hoc analyses revealed groups given SB prior to Acquisition 1 (SB/Veh, SB/SB) and Acquisition 2 (Veh/SB, SB/SB) had lower food cup responding during the CS presentations compared to the Veh/Veh group (ps < 0.05; Fig 3B). There were no differences between SB groups (ps > 0.05). All groups responded similarly during the pre-CS and post-CS periods (ps > 0.05).

Figure 3.

All groups significantly decreased latency to approach the food cup as the session progressed (Fig. 3C). The main effect of CS was confirmed by a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (F (3, 28) = 8.42, p < 0.001). However, groups treated with SB had overall greater latencies to approach the food cup compared to the Veh/Veh group during the session (Fig.3D). The two-way ANOVA found a main effect of Acquisition 1 Treatment (F (3, 28) = 7.79, p < 0.01), an approaching main effect of Acquisition 2 Treatment (F (3, 28) = 3.95, p = 0.057), but no interaction (p > 0.05). Post hoc analyses revealed groups given SB prior to Acquisition 1 (SB/Veh, SB/SB) and Acquisition 2 (Veh/SB, SB/SB) were slower to approach the food cup compared to the Veh/Veh group (ps < 0.05).

Similar to Acquisition 1, all groups spent similar amounts of time sitting, sniffing, walking, grooming, and expressing food cup behavior during the ITIs (Table 1). A minimal difference was found in rearing between two groups. In the two-way ANOVA, there was a main effect of Acquisition 1 Treatment (F (3, 28) = 4.29, p < 0.05), but no effect of Acquisition 2 Treatment or interaction (ps > 0.05). Further analysis showed the Veh/SB group had less rearing compared to the SB/SB group (p < 0.05) with no other differences between groups (ps > 0.05).

3.2. Experiment 2: Effect of SB on the extinction of Pavlovian appetitive conditioning

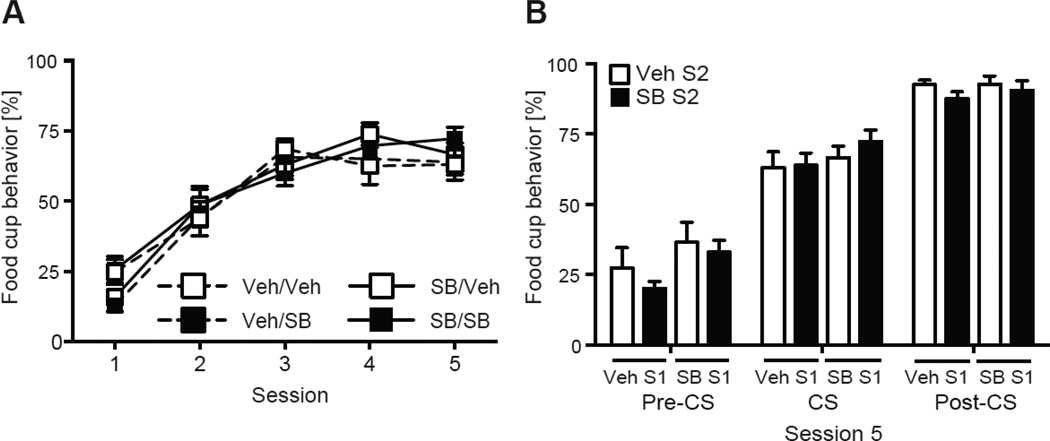

A separate cohort of rats underwent five acquisition sessions, drug free. All rats robustly learned the CS-US association across the five sessions of acquisition. These findings were expected given all groups underwent conditioning drug free, and allocated groups are based on drug treatment during extinction. Repeated measures ANOVA confirmed a significant increase in food cup responding, specifically during the CS periods across sessions (F (3, 28) = 90.42, p < 0.001; Fig. 4A). All groups had similar responding during the pre-CS, CS, and post-CS periods during the last session (ps > 0.05; Fig 4B).

Figure 4.

Additionally, all rats showed a significant decrease in latency across the five sessions (data not shown). A repeated measures ANOVA found a significant decrease in latency to approach the food cup (F (3, 28) = 146.88, p < 0.001), and all groups had similar latencies to approach the food cup during each session (ps > 0.05).

3.2.1. Extinction 1

Pretreatment with SB did not affect extinction learning compared to the vehicle group during the first extinction session (Fig. 5), evident by a similar decrease in food cup responding during the CS presentations (Fig. 5A). A group by CS repeated measures ANOVA found a significant effect of CS (F (1, 30) = 3.13, p < 0.01). There were no differences between groups during the pre-CS, CS, and post-CS periods (ps > 0.05; Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Latency to approach the food cup after CS onset increased across Extinction 1 (Fig. 5C), confirming extinction learning. A group by CS repeated measures ANOVA confirmed an effect of CS (F (1, 30) = 2.83, p < 0.01). There were no differences between groups (p > 0.05; Fig. 5D).

Furthermore, SB treatment did not affect any of the behaviors measured during the ITIs compared to the vehicle group (ps > 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Locomotor behaviors during extinction sessions. Values represent percentage (mean ± SEM) of all observed behaviors during the inter-trial intervals for SB-334867 (SB) and vehicle (Veh) treated groups.

| Extinction 1 | Extinction 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veh | SB | Veh/Veh | Veh/SB | SB/Veh | SB/SB | |

| Sitting | 29.72±2.9 | 33.50±4.2 | 33.53±3.5 | 33.22±4.6 | 28.42±4.6 | 37.09±4.2 |

| Sniffing | 20.15±2.9 | 17.55±1.9 | 16.76±3.5^ | 24.64±1.8*^ | 19.09±3.8 | 13.70±1.8* |

| Walking | 9.97±1.1 | 9.58±1.1 | 8.52±1.0 | 11.05±0.7 | 9.38±1.5 | 8.45±1.4 |

| Rearing | 12.08±1.0 | 9.55±2.4 | 13.71±2.0 | 7.72±1.4 | 10.08±2.5 | 9.93±2.0 |

| Grooming | 3.63±0.5 | 4.99±0.6 | 7.03±1.2 | 5.79±1.2 | 6.49±1.6 | 10.56±3.2 |

| Food cup | 23.20±2.9 | 23.70±3.8 | 19.66±4.0 | 16.69±3.6 | 25.57±5.6 | 18.30±3.1 |

p<0.05 between groups

p=0.06 between groups

3.2.2. Extinction 2

Pretreatment with SB affected the expression of extinction learning during the second extinction session, specifically during the post-CS periods when pellets were previously delivered during conditioning (Fig. 6). A two-way ANOVA confirmed a main effect of Extinction 1 Treatment (F (3, 28) = 4.93, p < 0.05) during the post-CS period, with no effect of Extinction 2 Treatment or interaction (ps > 0.05). Post hoc analyses confirmed the SB/Veh displayed more food cup behavior compared to the Veh/Veh and Veh/SB groups (ps < 0.05) and the difference approached significance with the SB/SB group (p = 0.07; Fig. 6B). There were no differences between the other three groups during the post-CS periods (ps > 0.05), and no differences between any groups during the pre-CS or CS periods (ps > 0.05). We also assessed conditioned responding during the first block of the post-CS (Fig. 6A), and a two-way ANOVA confirmed a main effect of Extinction 1 treatment (F (3, 28) = 6.64, p < 0.05) and a main effect of Extinction 2 treatment (F (3, 28) = 6.14, p < 0.05). Post hoc analysis revealed the SB/Veh group had higher responding compared to the Veh/SB (p < 0.05) and Veh/Veh (p < 0.10) groups, while the Veh/SB group had lower responding than the Veh/Veh group (p < 0.10).

Figure 6.

The SB/Veh group maintained faster latencies to respond to the food cup compared to other groups, which showed evidence of extinction learning with longer latencies (Fig. 6C). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA found a significant effect of CS (F (3,28) = 7.44, p < 0.05) and a CS by Extinction 2 Treatment interaction (F (3,28) = 7.24, p < 0.05) on latency. Post hoc analyses revealed groups given SB prior to Extinction session 2 (Veh/SB and SB/SB) significantly increased their latency during the last two CSs compared to the first two CSs (ps < 0.05; Fig. 6C). The groups given vehicle prior to Extinction 2 (SB/Veh and Veh/Veh) maintained similar latency responding across the session (ps > 0.05). Additionally, the SB/Veh group was faster to approach the food cup during the last two CSs compared to the Veh/SB and SB/SB groups (p = 0.05 and p < 0.05, respectively) but not the Veh/Veh group (p > 0.05). No differences were found between the other three groups during the last two CSs (ps > 0.05), or during the average latency responding (ps > 0.05, Fig. 6D).

All groups expressed similar behavior during the ITIs, except for sniffing (Table 2). A two-way ANOVA found an Extinction 1 Treatment by Extinction 2 Treatment interaction (F (3,28) = 5.35, p < 0.05). Post hoc analyses revealed the Veh/SB group spent a higher percentage of time sniffing compared to the SB/SB group (p < 0.05) and close to significant compared to the Veh/Veh group (p = 0.06), but not different from the SB/Veh group (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

The current study found that systemic administration of the OX1R antagonist, SB-334867 (SB), attenuated the acquisition and extinction of Pavlovian appetitive conditioning. In Experiment 1, administration of SB prior to the first session of acquisition had no effect on the expression of learning—food cup behavior or latency to approach the food cup—during that session. However, both measures of learning were attenuated during the second session in groups that received SB prior to either the first or second session of acquisition. In Experiment 2, we found a similar pattern, in that SB had an effect during the second, but not the first, extinction session. Specifically, the group that received SB prior to the first session and vehicle prior to the second session showed impaired extinction during the second session. These results demonstrate orexin signaling via the OX1R mediates the acquisition and extinction of cue-food associations.

The learning impairments observed in the current study were not simply due to nonspecific changes caused by SB administration either in locomotor activity or in reduced consumption of the training food pellets. The current study used the highest known dose that does not impair locomotor abilities (20mg/kg), yet is effective in appetitive learning studies (e.g. [25]). Accordingly, the current study found no effects on several measures of locomotor activity, including sitting, sniffing, walking, rearing, grooming and food cup behavior during the ITIs (with two small exceptions, see Results 3.1.2. and 3.2.2. for details). Additionally, we found that groups pretreated with SB decreased food cup behavior during acquisition, but maintained food cup behavior at the acquired high levels during extinction. This demonstrates the effects of SB were specific to the expression of learning in the direction distinct to the learning paradigm, rather than changes in locomotion or general arousal. Notably, in the extinction sessions the cue is presented without food pellets, and therefore SB administration specifically interfered with the cue-no reward learning. Finally, during the acquisition sessions all rats retrieved and consumed all delivered food pellets, indicating SB did not interfere with food consumption, even though SB has been shown to decrease consumption [10,11].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that orexin signaling is necessary for optimal acquisition of Pavlovian cue-food associations. Our findings suggest that orexin signaling is specifically required for the consolidation and recall of cue-food learning. Orexin blockade during the first acquisition session did not affect conditioned responding within the session, but selectively decreased conditioned responding during the second session when vehicle was administered, suggesting a selective impairment in the consolidation occurred after the first session. SB circulates in the brain and blood for at least 4 hours post-injection [29], indicating a plausible time course to affect consolidation. Impairments in the recall of the acquired learning from the first session were evident by a significant decrease in conditioned responding in the group that received SB during the second session, but received vehicle prior to the first session of acquisition.

The studies here were conducted under food restricted conditions, and the results from Experiment 1 are particularly interesting since all SB groups displayed lower conditioned responding, even though the motivation to seek food should be increased due to food restriction. During periods of hunger, the stomach-derived hormone, ghrelin [30,31] increases the motivation to eat and seek food [32–34] and the neural mechanisms of ghrelin involve action on orexin neurons [32,35,36]. In the current study specific reduction in conditioned responding caused by OX1R blockade may have interfered with the interaction between ghrelin and orexin.

The current results are in agreement with prior appetitive and aversive behavioral studies that demonstrated an important role for orexin in the acquisition of learning. In appetitive tasks, orexin signaling via OX1R was necessary for instrumental learning [15] and taste preference learning [37]. Additionally, the acquisition and recall of conditioned place preference activated orexin neurons and required signaling at the OX1R for other rewards, including morphine [27,38–41] and cocaine [27], but not alcohol [42]. In a spatial learning task, central administration of SB impaired the acquisition, consolidation, and recall of Morris water maze learning [43,44], while orexin-A administration also impaired learning of this task [45]. In aversive paradigms, orexin signaling during fear conditioning and during the consolidation period following training was necessary for successful learning and memory [46–48], and orexin also mediates the fear potentiated startle response [49]. Interestingly, orexin blockade enhanced taste aversion learning [37], and central administration of orexin-A enhanced within session avoidance learning, the consolidation of avoidance learning, and the retrieval of this learning [50–52].

Interestingly, a prior study found no differences in conditioned approach behavior between groups repeatedly administered SB or vehicle across seven sessions of cue-food conditioning [13]. Several methodological differences could explain why the current findings differ, including differences in drug concentration and administration timing, the length of training, and procedural differences. Our study used a slightly higher concentration of SB (20mg/kg versus 15mg/kg), and the drug was administered 30 min (versus 15 min) prior to behavioral training. There were also differences in the training protocol, including the number of training sessions (2 versus 7), the number of CS-US presentations per session (8 versus 30), the CSs (tone versus tone and light), and the behavioral measures of learning (percentage of food cup behavior during the CS and latency versus proportion of nosepokes during the CS relative to total nosepokes during the session). Finally, the crossover design in our study enabled comparisons across four different treatment conditions that revealed specific consolidation and recall effects, which would not be possible to assess with fewer groups.

In addition to the SB effects on acquisition, our findings demonstrated OX1R blockade interfered with appetitive extinction learning. Orexin blockade during the first extinction session did not affect conditioned responding within the session; however, when vehicle was administered prior to the second session, conditioned responding was maintained at high levels indicating impaired extinction. These findings suggest SB did not impair the initial extinction learning during the first session, but interfered with the consolidation of that learning. There was no overall effect on recall; however, the Veh/SB group had lower responding during the first block of the second extinction session. This transient effect may reflect better recall of extinction learning or may reflect impaired conditioned responding of recall. It is important to note that this impairment in the SB/Veh group cannot be attributed to a state-dependent learning effect, since the Veh/SB group, which was also in a different state from the first session, did not show a similar overall deficit during the second extinction session. Interestingly, the group that received SB prior to both extinction sessions had similar conditioned responding compared to the Veh/Veh group. One interpretation of these results is that the behavior of the SB/SB group reflects the summation of the SB effects on consolidation and on recall, which were in opposite directions - SB/Veh maintained high conditioned responding, while Veh/SB had transient low conditioned responding.

These findings are in agreement with prior evidence for the role of orexin in extinction. Extinction of lever pressing for sucrose was impaired in female rats by OX1R blockade [17]. Activation of orexin neurons (measured by Fos induction) in response to conditioned cues for food [9,16,27,28], or drugs [27,53–55] during tests conducted without rewards might also reflect a function in extinction. Similar to appetitive tasks, orexin manipulations also interfered with extinction in aversive tasks, however the effects observed were opposite. For example, orexin receptor antagonism facilitated, while orexin-A administration attenuated, fear extinction, and the effects occurred particularly during the consolidation period [46].

Orexin function during learning could reflect its suggested role in mediating motivation and attention towards biologically relevant events [2,3,56–58]. Impaired learning under SB treatment in the current study could therefore reflect a decrease in motivation, attention, or both during learning. Indeed, orexin signaling is necessary for the motivation to initially seek food [13,15–18,59] and drugs ([59–66] for reviews, see [1,3,67]), and the motivation to seek reward during extinction [65,68,69]. In addition, orexin signaling blockade decreased attention during a signal detection task [70]. Attentional processing in associative learning tasks was impaired by unilateral orexin saporin lesions, which destroyed a majority of orexin neurons within the lateral hypothalamus [71]. Furthermore, central administration of orexin-B, which has a lower affinity for orexin 1 receptors than orexin-A [5], enhanced accuracy on an attention task [72].

In the current study orexin signaling at OX1R was blocked systemically, and therefore our results do not indicate the critical neural sites where it acts to mediate the effects observed on appetitive acquisition and extinction. Nevertheless, recent work has identified specific cell groups within the amygdala, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the lateral hypothalamus that are recruited during the acquisition of cue-food associations [26,73]. These regions contain OX1R [74–76] and receive projections from orexin neurons [77] making them primary regions of interest for orexin signaling during learning. Additional forebrain regions may be important sites for orexin modulation during food intake and learning, including the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus [25] and hindbrain regions, including the locus coeruleus [47,48] and nucleus of the solitary tract [78]. Neural mechanisms of appetitive extinction have been minimally explored, but based on differences in recall between acquisition and extinction observed here, other regions, in addition to the aforementioned areas, could be critical in appetitive extinction learning (for review, see [79]). For that reason, the recall of extinction may be sufficiently mediated by a brain region without OX1Rs, which would not be affected by SB administration, and would function optimally in the SB treated recall groups, as supported by the current results. Future studies are needed to identify critical neural circuitries where orexin signaling mediates appetitive associative learning and memory.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the current study demonstrated OX1R signaling mediates cue-food acquisition and extinction learning, and may be necessary for optimal consolidation and recall of learning. These findings are important for understanding the mechanisms underlying food cue driven behaviors. Notably, food cues can drive feeding in the absence of physiological hunger, and that overeating depends on orexin [25]. The evidence provided here that orexin is also critical during the initial acquisition and extinction learning of these food cues, conducted under food deprivation, suggests a common mechanism may mediate the initial encoding and subsequent motivation to overeat in the presence of food cues independent of physiological hunger state.

Highlights.

Investigated orexin necessity in cue-food acquisition and extinction learning

Orexin receptor blockade impaired consolidation and recall during acquisition

Orexin receptor blockade impaired consolidation during extinction

Acknowledgments

We thank the Society for the Study of Ingestive Behavior for the New Investigator Travel Award awarded to S.E.K., and thank Heather Mayer for technical assistance. This research was supported by the National Institute of Health grant DK085721 to G.D.P.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cason AM, Smith RJ, Tahsili-Fahadan P, Moorman DE, Sartor GC, Aston-Jones G. Role of orexin/hypocretin in reward-seeking and addiction: implications for obesity. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(5):419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahler SV, Moorman DE, Smith RJ, James MH, Aston-Jones G. Motivational activation: a unifying hypothesis of orexin/hypocretin function. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(10):1298–1303. doi: 10.1038/nn.3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakurai T. The role of orexin in motivated behaviours. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(11):719–731. doi: 10.1038/nrn3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, et al. The hypocretins: Hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92(4):573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmquist JK, Elias CF, Saper CB. From lesions to leptin: hypothalamic control of food intake and body weight. Neuron. 1999;22(2):221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wise RA. Lateral hypothalamic electrical stimulation: does it make animals ‘hungry’? Brain Res. 1974;67(2):187–209. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scammell TE, Winrow CJ. Orexin receptors: pharmacology and therapeutic opportunities. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:243–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi DL, Davis JF, Fitzgerald ME, Benoit SC. The role of orexin-A in food motivation, reward-based feeding behavior and food-induced neuronal activation in rats. Neuroscience. 2010;167(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haynes AC, Jackson B, Chapman H, Tadayyon M, Johns A, Porter RA, et al. A selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist reduces food consumption in male and female rats. Regul Pept. 2000;96(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodgers RJ, Halford JCG, Nunes de Souza RL, Canto de Souza AL, Piper DC, Arch JRS, et al. SB-334867, a selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist, enhances behavioural satiety and blocks the hyperphagic effect of orexin-A in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13(7):1444–1452. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piccoli L, Di Bonaventura MVM, Cifani C, Costantini VJ, Massagrande M, Montanari D, et al. Role of orexin-1 receptor mechanisms on compulsive food consumption in a model of binge eating in female rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(9):1999–2011. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borgland SL, Chang SJ, Bowers MS, Thompson JL, Vittoz N, Floresco SB, et al. Orexin A/hypocretin-1 selectively promotes motivation for positive reinforcers. J Neurosci. 2009;29(36):11215–11225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6096-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair SG, Golden SA, Shaham Y. Differential effects of the hypocretin 1 receptor antagonist SB 334867 on high-fat food self-administration and reinstatement of food seeking in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):406–416. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharf R, Sarhan M, Brayton CE, Guarnieri DJ, Taylor JR, DiLeone RJ. Orexin signaling via the orexin 1 receptor mediates operant responding for food reinforcement. Biol Psychiatry. 2010b;67(8):753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cason AM, Aston-Jones G. Role of orexin/hypocretin in conditioned sucrose-seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2013a;226(1):155–165. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2902-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cason AM, Aston-Jones G. Role of orexin/hypocretin in conditioned sucrose-seeking in female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2014;86:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cason AM, Aston-Jones G. Attenuation of saccharin-seeking in rats by orexin/hypocretin receptor 1 antagonist. Psychopharmacology. 2013b;228(3):499–507. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuo E, Mochizuki A, Nakayama K, Nakamura S, Yamamoto T, Shioda S, et al. Decreased intake of sucrose solutions in orexin knockout mice. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;43(2):217–224. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birch LL, McPhee L, Sullivan S. Children's food intake following drinks sweetened with sucrose or aspartame: time course effects. Physiol Behav. 1989;45(2):387–395. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estes WK. Discriminative conditioning. II. Effects of a Pavlovian conditioned stimulus upon a subsequently established operant response. J Exp Psychol. 1948;38(2):173. doi: 10.1037/h0057525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reppucci CJ, Petrovich GD. Learned food-cue stimulates persistent feeding in sated rats. Appetite. 2012;59(2):437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weingarten HP. Conditioned cues elicit feeding in sated rats: a role for learning in meal initiation. Science. 1983;220(4595):431–433. doi: 10.1126/science.6836286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrovich GD. Forebrain networks and the control of feeding by environmental learned cues. Physiol. Behav. 2013;121:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole S, Mayer HS, Petrovich GD. Orexin/Hypocretin-1 Receptor Antagonism Selectively Reduces Cue-Induced Feeding in Sated Rats and Recruits Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Thalamus. Sci Rep. 2015b;5:16143. doi: 10.1038/srep16143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole S, Hobin MP, Petrovich GD. Appetitive associative learning recruits a distinct network with cortical, striatal, and hypothalamic regions. Neuroscience. 2015a;286:187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G. A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature. 2005;437(7058):556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature04071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrovich GD, Hobin MP, Reppucci CJ. Selective Fos induction in hypothalamic orexin/hypocretin, but not melanin-concentrating hormone neurons, by a learned food-cue that stimulates feeding in sated rats. Neuroscience. 2012;224:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishii Y, Blundell JE, Halford JCG, Upton N, Porter R, Johns A, et al. Anorexia and weight loss in male rats 24 h following single dose treatment with orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867. Behav Brain Res. 2005;157(2):331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, Schmidova K, Wisse BE, Weigle DS. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1714–1719. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tschöp M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000;407(6806):908–913. doi: 10.1038/35038090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu TM, Hahn JD, Konanur VR, Noble EE, Suarez AN, Thai J, et al. Hippocampus ghrelin signaling mediates appetite through lateral hypothalamic orexin pathways. Elife. 2015;4:e11190. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanoski SE, Fortin SM, Ricks KM, Grill HJ. Ghrelin signaling in the ventral hippocampus stimulates learned and motivational aspects of feeding via PI3K-Akt signaling. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):915–923. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker AK, Ibia IE, Zigman JM. Disruption of cue-potentiated feeding in mice with blocked ghrelin signaling. Physiol Behav. 2012;108:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrence CB, Snape AC, Baudoin FM, Luckman SM. Acute central ghrelin and GH secretagogues induce feeding and activate brain appetite centers. Endocrinology. 2002;143(1):155–162. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.1.8561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olszewski PK, Li D, Grace MK, Billington CJ, Kotz CM, Levine AS. Neural basis of orexigenic effects of ghrelin acting within lateral hypothalamus. Peptides. 2003;24(4):597–602. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(03)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mediavilla C, Cabello V, Risco S. SB-334867-A, a selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist, enhances taste aversion learning and blocks taste preference learning in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;98(3):385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris GC, Wimmer M, Randall-Thompson JF, Aston-Jones G. Lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons are critically involved in learning to associate an environment with morphine reward. Behav Brain Res. 2007;183(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narita M, Nagumo Y, Hashimoto S, Narita M, Khotib J, Miyatake M, et al. Direct involvement of orexinergic systems in the activation of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway and related behaviors induced by morphine. J Neurosci. 2006;26(2):398–405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2761-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharf R, Guarnieri DJ, Taylor JR, DiLeone RJ. Orexin mediates morphine place preference, but not morphine-induced hyperactivity or sensitization. Brain Res. 2010a;1317:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabaeizadeh M, Motiei-Langroudi R, Mirbaha H, Esmaeili B, Tahsili-Fahadan P, Javadi-Paydar M, et al. The differential effects of OX1R and OX2R selective antagonists on morphine conditioned place preference in naive versus morphine-dependent mice. Behav Brain Res. 2013;237:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voorhees CM, Cunningham CL. Involvement of the orexin/hypocretin system in ethanol conditioned place preference. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214(4):805–818. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2082-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akbari E, Naghdi N, Motamedi F. Functional inactivation of orexin 1 receptors in CA1 region impairs acquisition, consolidation and retrieval in Morris water maze task. Behav Brain Res. 2006;173(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akbari E, Naghdi N, Motamedi F. The selective orexin 1 receptor antagonist SB-334867-A impairs acquisition and consolidation but not retrieval of spatial memory in Morris water maze. Peptides. 2007;28(3):650–656. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aou S, Li XL, Li AJ, Oomura Y, Shiraishi T, Sasaki K, et al. Orexin-A (hypocretin-1) impairs Morris water maze performance and CA1-Schaffer collateral long-term potentiation in rats. Neuroscience. 2003;119(4):1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flores Á, Valls-Comamala V, Costa G, Saravia R, Maldonado R, Berrendero F. The hypocretin/orexin system mediates the extinction of fear memories. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(12):2732–2741. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sears RM, Fink AE, Wigestrand MB, Farb CR, de Lecea L, LeDoux JE. Orexin/hypocretin system modulates amygdala-dependent threat learning through the locus coeruleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(50):20260–20265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320325110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soya S, Shoji H, Hasegawa E, Hondo M, Miyakawa T, Yanagisawa M, et al. Orexin receptor-1 in the locus coeruleus plays an important role in cue-dependent fear memory consolidation. J Neurosci. 2013;33(36):14549–14557. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1130-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steiner MA, Lecourt H, Jenck F. The brain orexin system and almorexant in fear-conditioned startle reactions in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2012;223(4):465–475. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2736-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akbari E, Motamedi F, Naghdi N, Noorbakhshnia M. The effect of antagonization of orexin 1 receptors in CA 1 and dentate gyrus regions on memory processing in passive avoidance task. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187(1):172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jaeger LB, Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE. Effects of orexin-A on memory processing. Peptides. 2002;23(9):1683–1688. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Telegdy G, Adamik A. The action of orexin A on passive avoidance learning. Involvement of transmitters. Regul Pept. 2002;104(1):105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dayas CV, McGranahan TM, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Stimuli linked to ethanol availability activate hypothalamic CART and orexin neurons in a reinstatement model of relapse. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(2):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamlin AS, Newby J, McNally GP. The neural correlates and role of D1 dopamine receptors in renewal of extinguished alcohol-seeking. Neuroscience. 2007;146(2):525–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamlin AS, Clemens KJ, McNally GP. Renewal of extinguished cocaine-seeking. Neuroscience. 2008;151(3):659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boutrel B, Cannella N, de Lecea L. The role of hypocretin in driving arousal and goal-oriented behaviors. Brain Res. 2010;1314:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fadel J, Burk JA. Orexin/hypocretin modulation of the basal forebrain cholinergic system: role in attention. Brain Res. 2010;1314:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saper CB. Staying awake for dinner: hypothalamic integration of sleep, feeding, and circadian rhythms. Prog Brain Res. 2006;153:243–252. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)53014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Blockade of hypocretin receptor-1 preferentially prevents cocaine seeking: comparison with natural reward seeking. Neuroreport. 2014;25(7):485–488. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bentzley BS, Aston-Jones G. Orexin-1 receptor signaling increases motivation for cocaine-associated cues. Eur J Neurosci. 2015;41(9):1149–1156. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hutcheson DM, Quarta D, Halbout B, Rigal A, Valerio E, Heidbreder C. Orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 reduces the acquisition and expression of cocaine-conditioned reinforcement and the expression of amphetamine-conditioned reward. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22(2):173–181. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328343d761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lawrence AJ. Regulation of alcohol-seeking by orexin (hypocretin) neurons. Brain Res. 2010;1314:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Plaza-Zabala A, Flores Á, Martín-García E, Saravia R, Maldonado R, Berrendero F. A role for hypocretin/orexin receptor-1 in cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(9):1724–1736. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith RJ, See RE, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin signaling at the orexin 1 receptor regulates cue-elicited cocaine-seeking. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30(3):493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith RJ, Tahsili-Fahadan P, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin is necessary for context-driven cocaine-seeking. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(1):179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith RJ, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin 1 receptor antagonist reduces heroin self-administration and cue-induced heroin seeking. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(5):798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahler SV, Smith RJ, Moorman DE, Sartor GC, Aston-Jones G. Multiple roles for orexin/hypocretin in addiction. Prog Brain Res. 2012;198:79. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59489-1.00007-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou L, Ghee SM, Chan C, Lin L, Cameron MD, Kenny PJ, et al. Orexin-1 receptor mediation of cocaine seeking in male and female rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012a;340(3):801–809. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.187567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou L, Smith RJ, Do PH, Aston-Jones G, See RE. Repeated orexin 1 receptor antagonism effects on cocaine seeking in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2012b;63(7):1201–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boschen KE, Fadel JR, Burk JA. Systemic and intrabasalis administration of the orexin-1 receptor antagonist, SB-334867, disrupts attentional performance in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;206(2):205–213. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1596-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wheeler DS, Wan S, Miller A, Angeli N, Adileh B, Hu W, et al. Role of lateral hypothalamus in two aspects of attention in associative learning. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;40(2):2359–2377. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lambe EK, Olausson P, Horst NK, Taylor JR, Aghajanian GK. Hypocretin and nicotine excite the same thalamocortical synapses in prefrontal cortex: correlation with improved attention in rat. J Neurosci. 2005;25(21):5225–5229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cole S, Powell DJ, Petrovich GD. Differential recruitment of distinct amygdalar nuclei across appetitive associative learning. Learn Mem. 2013;20(6):295–299. doi: 10.1101/lm.031070.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435(1):6–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmitt O, Usunoff KG, Lazarov NE, Itzev DE, Eipert P, Rolfs A, et al. Orexinergic innervation of the extended amygdala and basal ganglia in the rat. Brain Struct Funct. 2012;217(2):233–256. doi: 10.1007/s00429-011-0343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trivedi P, Yu H, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LHT, Guan XM. Distribution of orexin receptor mRNA in the rat brain. FEBS letters. 1998;438(1):71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, et al. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kay K, Parise EM, Lilly N, Williams DL. Hindbrain orexin 1 receptors influence palatable food intake, operant responding for food, and food-conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231(2):419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3248-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peters J, Kalivas PW, Quirk GJ. Extinction circuits for fear and addiction overlap in prefrontal cortex. Learn Mem. 2009;16(5):279–288. doi: 10.1101/lm.1041309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]