Abstract

Residing in a high-poverty area has consistently been associated with higher mortality rates, but the association between poverty and mortality can change over time. We examine the association between neighborhood poverty and mortality in New York City (NYC) during 1990–2010 to document mortality disparity changes over time and determine causes of death for which disparities are greatest. We used NYC and New York state mortality data for years 1990, 2000, and 2010 to calculate all-cause and cause-specific age-adjusted death rates (AADRs) by census tract poverty (CTP), which is the proportion of persons in a census tract living below the federal poverty threshold. We calculated mortality disparities, measured as the difference in AADR between the lowest and highest CTP groups, within and across race/ethnicity, nativity, and sex categories by year. We observed higher all-cause AADRs with higher CTP for each year for all race/ethnicities, both sexes, and US-born persons. Mortality disparities decreased progressively during 1990-2010 for the NYC population overall, for each race/ethnic group, and for the majority of causes of death. The overall mortality disparity between the highest and lowest CTP groups during 2010 was 2.55 deaths/1000 population. The largest contributors to mortality disparities were heart disease (51.52 deaths/100,000 population), human immunodeficiency virus (19.96/100,000 population), and diabetes (19.59/100,000 population). We show that progress was made in narrowing socioeconomic disparities in mortality during 1990–2010, but substantial disparities remain. Future efforts toward achieving health equity in NYC mortality should focus on areas contributing most to disparities.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11524-016-0048-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mortality, Socioeconomic factors, Poverty, Geography, Ethnic groups

Introduction

A major goal of Healthy People 2020 is to achieve health equity and eliminate health disparities, including those that are based on socioeconomic status (SES) in addition to those on the basis of sex and race/ethnicity.1 To set priorities for eliminating health disparities, knowledge of where disparities exist and direction they are trending is important.

Mortality rates have declined in New York City (NYC) during the study period. In an analysis spanning 1990–2001, racial/ethnic minorities and residents of lower income neighborhoods experienced a proportionally greater decline in mortality compared with whites and residents of higher income neighborhoods.2 Nonetheless, substantial gaps remained with all-cause mortality rates 1.6 times higher among NYC’s poorest neighborhoods, compared with wealthiest neighborhoods. All-cause mortality rates have continued to decline since 2001,3 but subgroup and cause-specific trends by SES have not been described.

We describe the association between census tract-level poverty and mortality for three time points during a 20-year period, from 1990 to 2010. Census tract-level poverty is used as a standard SES variable in NYC, particularly for vital statistics data, which lack individual SES status but include a residential address.4 We explore this association within and among groups defined by race/ethnicity, nativity, and sex. Moreover, we investigate the contribution of specific causes of death to mortality disparities during that time. These analyses serve as baseline data for setting priorities and enable us to periodically assess progress in reducing socioeconomic mortality disparities over time. They also might provide a helpful example for other jurisdictions that have not examined mortality data by using SES measures.

Methods

Data Sources

Mortality data were derived from NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York State Department of Health vital statistics data files for years 1990, 2000, and 2010, coinciding with the decennial census when population counts and census tract poverty determinations are most accurate. These data included information regarding cause of death, age, sex, race/ethnicity, nativity, and census tract of residence at time of death. We coded underlying causes of death into mutually exclusive categories following National Center for Health Statistics standards by using the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision for 1990 deaths and Tenth Revision for 2000 and 2010 deaths. NYC census tract-specific population estimates by age, sex, and race/ethnic group stratified by poverty level were obtained from the 1990, 2000, and 2010 U.S. Census Bureau; 1990 population estimates were compiled by New York City Department of City Planning. This study underwent human subjects review at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and was determined to be non-research public health surveillance.

Census Tract-Level Poverty

Each death was geocoded to a specific census tract on the basis of residential street address at death. Census tract-level poverty was measured as the population percentage in a census tract living below the federal poverty threshold. Census tract poverty is a validated SES measure that correlates with individual-level measures and captures neighborhood-specific socioeconomic features that might apply to all persons residing in a given neighborhood.5–7 Census tract poverty estimates were obtained from the 1990 and 2000 U.S. Census Bureau long form sample for the years 1990 and 2000 and from the 2008–2012 American Community Survey for 2010. We defined six census tract poverty categories as follows: neighborhoods with <5 %, 5–<10 %, 10–<20 %, 20–<30 %, 30–<40 %, or ≥40 % of households living below the federal poverty threshold. For analyses with smaller counts (i.e., causes of death) we collapsed census tract poverty to the following four levels: <10 %, 10–<20 %, 20–<30 %, and ≥30 %.

Race/Ethnicity and Nativity

For 2000 and 2010 data, analysis by race/ethnicity was limited to four race/ethnic categories, including non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian, comprising approximately 96 % of the NYC population. Denominator data for the non-Hispanic Asian category were unavailable for 1990; therefore, three race/ethnic categories comprising 93 % of the NYC population were used for 1990 data. Observations belonging to other race/ethnic categories (e.g., Native American) or with unknown race/ethnicity were excluded from analyses where race/ethnicity was a covariate. An option to select multiple races was added to US Census forms in 2000 and to NYC death certificates in 2003. In 2000, 2.8 % of the NYC population was estimated by the US Census as belonging to multiple races and was excluded from the denominator. In 2010 an estimated 1.8 % of the NYC population was excluded from the denominator and 0.4 % of NYC deaths were excluded from the numerator as belonging to multiple races. Nativity was dichotomized as US-born (states or territories in the USA) or foreign-born persons. Population denominators for nativity at the census tract-level were estimated from the U.S. Census Bureau long form sample for 1990 and 2000 and the 2008–2012 American Community Survey for 2010. The estimated percentage of foreign-born persons in each census tract was applied to the actual population to estimate number of foreign-born persons in each census tract.

Mortality Rates and Excess SES-Related Deaths

We computed all-cause age-adjusted death rates (AADRs) by 6-category census tract poverty, race/ethnicity, nativity, and sex for 1990, 2000, and 2010. We also calculated cause-specific AADRs for the 10 leading causes of death by four-category census tract poverty for 1990, 2000, and 2010. We calculated differences in all-cause and cause-specific AADRs between the highest and lowest census tract poverty groups during 1990–2010. All AADRs were standardized to the 2000 US projected population. In order to estimate excess deaths during 2010 related to census tract poverty, we applied age-specific death rates for the highest SES census tracts (<5 % below poverty) to the age-specific population denominators for each of the other census tract poverty groups to determine the expected number of deaths should each group have the same mortality rates as the highest SES census tracts. We then subtracted the expected from the observed number of deaths to determine the excess. We tested the statistical significance of changes in mortality rates over time by using the chi-square test for trend.

Results

All-Cause Mortality

From 1990 to 2010, NYC’s population distribution shifted away from the highest (≥40 %) and two lowest (<10 %) census tract poverty groups toward a progressively greater proportion of the population residing in middle poverty census tracts, particularly the poorer middle poverty groups (Table 1). The proportion of the population residing in census tracts with 20 to 40 % of the population living below the federal poverty threshold increased from 24 % during 1990 to 34 % during 2010. All-cause AADR decreased for each census tract poverty group over time, from 7.98 (95 % CI: 7.82, 8.14) to 5.30 (5.16, 5.45) deaths/1000 population for the lowest census tract poverty (low poverty) group, and from 13.63 (13.34, 13.92) to 7.85 (7.62, 8.09) for the highest census tract poverty (high poverty) group (Table 1). The decrease was largest for the high poverty group, narrowing the disparity (difference in rates) between the high and low poverty groups from 5.65/1000 population during 1990 to 2.55/1000 population during 2010.

TABLE 1.

Age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate (AADR) per 1000 population by census tract poverty, New York City, 1990, 2000, and 2010a

| Percentage below poverty | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deathsb | Population | AADR [95 % CI] | Deaths | Population | AADR [95 % CI] | Deaths | Population | AADR [95 % CI] | |

| Overall | 71,179 | 7,322,564 | 9.89 [9.82, 9.97] | 58,861 | 8,008,278 | 7.70 [7.64, 7.77] | 50,781 | 8,175,133 | 6.05 [6.00, 6.10] |

| <5 % | 9329 | 1,023,161 | 7.98 [7.82, 8.14] | 4429 | 559,559 | 6.38 [6.19, 6.57] | 5175 | 711,124 | 5.30 [5.16, 5.45] |

| 5–<10 % | 16,317 | 1,617,217 | 8.68 [8.55, 8.82] | 11,907 | 1,515,079 | 6.91 [6.79, 7.04] | 9922 | 1,530,026 | 5.41 [5.30, 5.51] |

| 10–<20 % | 19,089 | 1,924,936 | 9.45 [9.32, 9.59] | 15,926 | 2,237,334 | 7.07 [6.96, 7.18] | 14,374 | 2,399,101 | 5.71 [5.61, 5.80] |

| 20–<30 % | 10,064 | 1,058,649 | 10.39 [10.18, 10.59] | 12,023 | 1,717,794 | 7.70 [7.56, 7.84] | 10,329 | 1,784,561 | 6.31 [6.19, 6.43] |

| 30–<40 % | 6696 | 728,945 | 11.84 [11.55, 12.13] | 7252 | 1,040,406 | 8.86 [8.65, 9.06] | 6324 | 1,029,881 | 7.01 [6.84, 7.19] |

| ≥40 % | 9296 | 952,600 | 13.63 [13.34, 13.92] | 6482 | 923,655 | 10.27 [10.01, 10.52] | 4371 | 706,908 | 7.85 [7.62, 8.09] |

CI confidence interval

aData from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York State Department of Health Vital Statistics data files, the 1990 and 2000 US Census, and the 2008–2012 American Community Survey

bNumber of deaths by census tract poverty do not add up to total deaths due to observations with missing census tract data

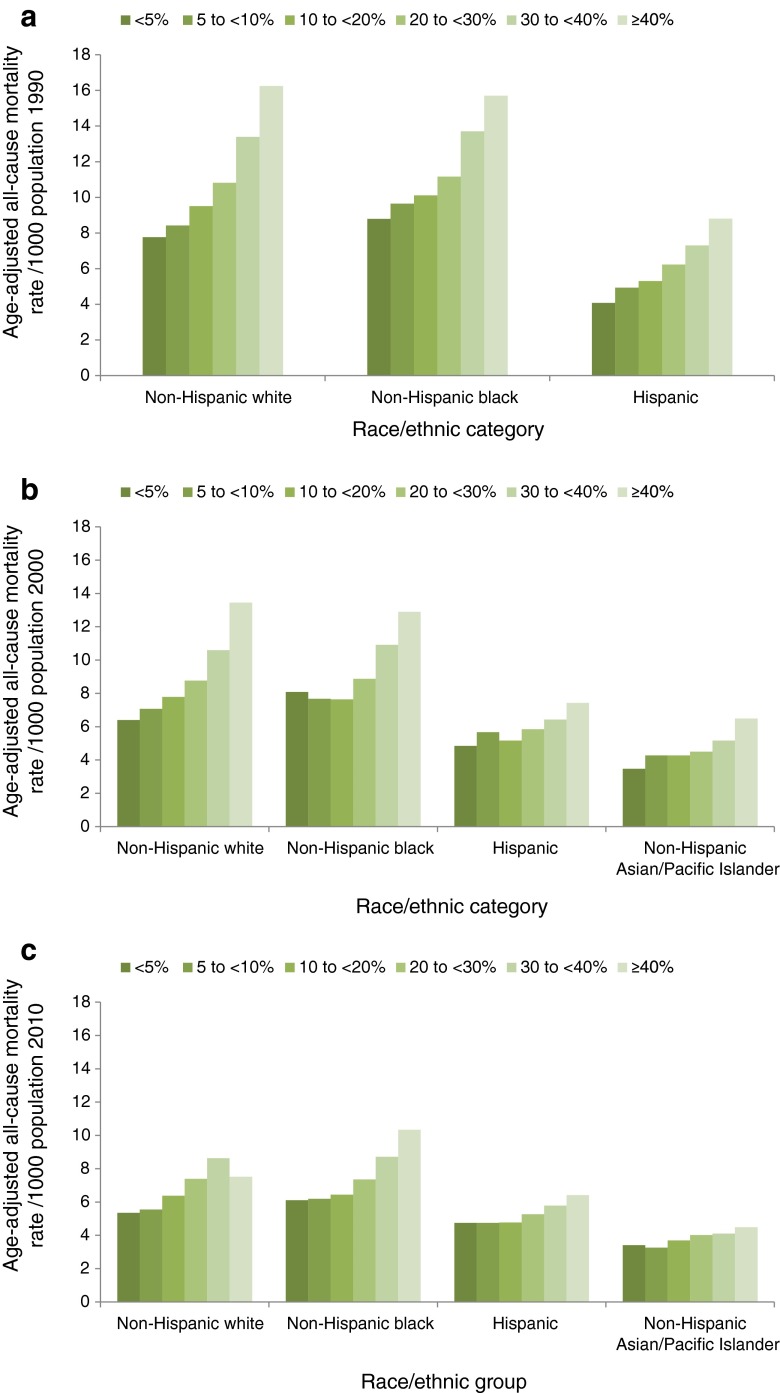

Higher AADRs were observed with higher census tract poverty for each of the three years (Table 1). This pattern was also observed upon examination of mortality by census tract poverty within race/ethnic groups and sex categories. Within each race/ethnic group, a progressive decrease in mortality occurred during the 20-year period and the mortality disparity between high and low poverty groups decreased (Fig. 1a–c).

FIG. 1.

a Age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate per 1000 population by census tract povertya and race/ethnicity, New York City, 1990. Trend from lowest to highest poverty level is statistically significant for each race/ethnic group (p < 0.05, chi-square for trend). b Age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate per 1000 population by census tract povertyb and race/ethnicity, New York City, 2000. Trend from lowest to highest poverty level is statistically significant for each race/ethnic group (p < 0.05, chi-square for trend). c Age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate per 1000 population by census tract povertyc and race/ethnicity, New York City, 2010. Trend from lowest to highest poverty level is statistically significant for each race/ethnic group (p < 0.05, chi-square for trend).

The mortality disparity between high and low poverty groups decreased significantly among non-Hispanic whites (from 8.48 during 1990 to 2.16 during 2010),1 Hispanics (from 4.73 to 1.66)1 and non-Hispanic blacks (from 6.91 to 4.23).1 Data for non-Hispanic Asians were not available for 1990. Mortality disparity decreased among non-Hispanic Asians from 3.02 during 2000 to 1.08 during 2010 but this difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, a progressive decrease in mortality over time for males and females in all poverty groups was observed, with larger decreases observed in the high poverty groups. Moreover, larger decreases were observed in mortality for males than females, resulting in a narrowing of the disparity between males and females. The decrease in AADR during 1990–2010 was 5.27 among males1 and 2.76 among females1, resulting in a decrease in the male to female mortality disparity from 4.78 during 1990 to 2.27 during 2010.

The results by nativity were more complex, with findings among the US-born population similar to the overall findings, whereas findings among the foreign-born population were less consistent. Among US-born persons, higher AADRs were observed with higher census tract poverty for each period, and a progressive decrease in mortality over time for each of the six poverty groups was detected (Table 2). The decrease was largest for the high poverty group, narrowing the difference in rates among high and low poverty groups from 6.41 during 1990 to 2.93 during 2010.

TABLE 2.

Age-adjusted all-cause mortality rate (AADR) per 1000 population by census tract poverty (CTP) and nativity, New York City, 1990, 2000, and 2010a

| CTP | Year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | ||||||||

| Deaths | Population | AADR [95 % CI] | Deaths | Population | AADR [95 % CI] | Deaths | Population | AADR [95 % CI] | ||

| US-born | Overall | 49,163 | 5,224,390 | 9.49 [9.41, 9.58] | 39,835 | 5,113,828 | 8.07 [7.99, 8.15] | 33,185 | 5,143,888 | 6.24 [6.17, 6.31] |

| <5 % | 6675 | 818,172 | 7.08 [6.91, 7.26] | 3316 | 431,629 | 6.15 [5.94, 6.36] | 3712 | 517,568 | 5.18 [5.01, 5.35] | |

| 5–<10 % | 10,878 | 1,188,214 | 7.91 [7.76, 8.06] | 8458 | 1,094,884 | 6.83 [6.68, 6.97] | 6931 | 1,060,281 | 5.40 [5.27, 5.53] | |

| 10–<20 % | 12,136 | 1,238,106 | 9.25 [9.08, 9.42] | 10,033 | 1,280,258 | 7.69 [7.54, 7.85] | 8694 | 1,396,523 | 5.92 [5.79, 6.04] | |

| 20–<30 % | 6515 | 683,146 | 10.28 [10.03, 10.53] | 7425 | 964,399 | 8.48 [8.29, 8.68] | 6155 | 1,022,695 | 6.56 [6.40, 6.73] | |

| 30–<40 % | 4934 | 511,632 | 12.18 [11.84, 12.54] | 4936 | 650,023 | 9.64 [9.37, 9.91] | 4209 | 637,499 | 7.57 [7.35, 7.81] | |

| ≥40 % | 7767 | 785,120 | 13.49 [13.18, 13.8] | 5094 | 692,635 | 10.49 [10.20, 10.79] | 3281 | 509,322 | 8.11 [7.83, 8.40] | |

| Foreign-born | Overall | 20,483 | 2,081,118 | 10.12 [9.98, 10.26] | 7766 | 2,867,793 | 6.55 [6.46, 6.65] | 16,694 | 3,017,713 | 5.45 [5.36, 5.53] |

| <5 % | 2559 | 204,989 | 11.22 [10.79, 11.67] | 1065 | 125,757 | 6.73 [6.33, 7.14] | 1340 | 193,556 | 5.17 [4.89, 5.46] | |

| 5–<10 % | 5212 | 429,003 | 10.25 [9.98, 10.54] | 3252 | 419,468 | 6.79 [6.56, 7.03] | 2762 | 469,745 | 4.93 [4.75, 5.12] | |

| 10–<20 % | 6534 | 686,830 | 9.33 [9.10, 9.56] | 5615 | 955,160 | 5.95 [5.79, 6.11] | 5410 | 1,002,578 | 5.17 [5.04, 5.31] | |

| 20–<30 % | 3290 | 375,503 | 9.99 [9.65, 10.34] | 4281 | 750,190 | 6.33 [6.15, 6.53] | 4032 | 761,866 | 5.69 [5.52, 5.87] | |

| 30–<40 % | 1585 | 217,313 | 9.83 [9.34, 10.34] | 2170 | 389,130 | 7.06 [6.76, 7.36] | 2053 | 392,382 | 6.00 [5.74, 6.26] | |

| ≥40 % | 1197 | 167,480 | 11.29 [10.64, 11.98] | 1154 | 228,088 | 8.14 [7.67, 8.64] | 1046 | 197,586 | 6.88 [6.46, 7.31] | |

CI confidence interval

aData from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York State Department of Health Vital Statistics data files, the 1990 and 2000 US Census and the 2008–2012 American Community Survey

Among foreign-born persons, a U-shaped association was observed between mortality and census tract poverty during 1990 and 2000, with higher AADRs among the high and low poverty groups than the middle poverty groups. However, progressively higher AADRs were observed with higher census tract poverty during 2010 (Table 2). Mortality disparities between the high and low poverty groups were much more limited among foreign-born than US-born persons. Although a progressive decrease in mortality over time for each of the six poverty groups occurred, the decrease during 1990–2010 was greater for those in the low poverty group than in the high poverty group (6.05/1000 population versus 4.41/1000 population).

The mortality disparity between the US-born and foreign-born populations changed over time. During 1990, all-cause AADR was slightly higher for foreign-born than US-born persons (Table 2). During 2000 and 2010, AADR was lower among foreign-born persons. By census tract poverty, AADRs were lower among foreign-born persons for the three highest census tract poverty groups in all three periods. During 2010, AADR was approximately equal for foreign-born and US-born persons among the low poverty group, but was lower among foreign-born persons for all other census tract poverty groups with the biggest differences between foreign-born and US-born mortality rates among the high poverty groups.

Cause-Specific Mortality

Cause-specific AADRs decreased over time for each leading cause of death except diabetes mellitus and hypertension and renal diseases. The largest decreases among overall AADRs were observed for heart diseases (175.39/100,000 population), malignant neoplasms (54.13/100,000 population), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease (46.73/100,000 population) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Age-adjusted cause-specific mortality rates (AADR) per 100,000 population for high and low census tract poverty (CTP) groups, New York City, 1990, 2000, and 2010a

| Age-adjusted Mortality Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of death | Year | All CTP groups | Low poverty (<10 %) | High poverty (≥30 %) |

| Heart diseases | 1990 | 384.02 | 356.26 | 421.03 |

| 2000 | 321.59 | 298.05 | 343.21 | |

| 2010 | 208.63 | 187.37 | 238.89 | |

| Malignant neoplasms | 1990 | 203.64 | 197.47 | 223.80 |

| 2000 | 173.85 | 174.38 | 192.61 | |

| 2010 | 149.51 | 150.49 | 162.72 | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus disease | 1990 | 55.90 | 34.67 | 97.40 |

| 2000 | 23.41 | 6.81 | 57.15 | |

| 2010 | 9.17 | 2.84 | 22.43 | |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 1990 | 49.59 | 41.53 | 67.21 |

| 2000 | 29.76 | 25.95 | 35.71 | |

| 2010 | 28.51 | 24.74 | 34.93 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1990 | 38.11 | 32.14 | 50.02 |

| 2000 | 25.91 | 21.87 | 34.45 | |

| 2010 | 19.00 | 16.63 | 24.38 | |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 1990 | 23.15 | 20.03 | 30.75 |

| 2000 | 21.48 | 20.22 | 26.16 | |

| 2010 | 20.66 | 19.23 | 25.12 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1990 | 13.67 | 9.45 | 25.23 |

| 2000 | 23.59 | 15.08 | 42.89 | |

| 2010 | 20.14 | 12.26 | 32.22 | |

| Homicide | 1990 | 27.28 | 10.06 | 58.98 |

| 2000 | 8.10 | 2.62 | 14.74 | |

| 2010 | 6.30 | 3.03 | 11.60 | |

| Accidents except drug poisoning | 1990 | 21.62 | 18.81 | 27.81 |

| 2000 | 13.02 | 11.2 | 14.17 | |

| 2010 | 10.92 | 11.16 | 10.73 | |

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 1990 | 13.49 | 7.86 | 27.83 |

| 2000 | 7.00 | 3.67 | 12.89 | |

| 2010 | 5.77 | 3.95 | 8.54 | |

| Psychiatric substance use and accidental drug poisoning | 1990 | 7.52 | 3.44 | 18.25 |

| 2000 | 9.69 | 4.64 | 19.41 | |

| 2010 | 6.91 | 5.16 | 12.27 | |

| Hypertension and renal diseases | 1990 | 5.48 | 3.37 | 9.86 |

| 2000 | 10.12 | 6.69 | 17.01 | |

| 2010 | 11.80 | 8.32 | 17.76 | |

aData from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York State Department of Health Vital Statistics data files, the 1990 and 2000 US Census, and the 2008–2012 American Community Survey

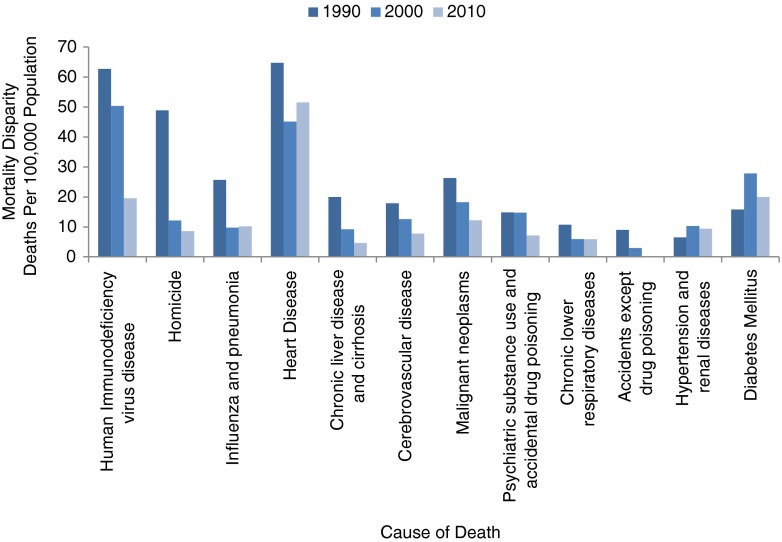

During 1990, mortality was progressively greater with higher census tract poverty for all leading causes of death except malignant neoplasms and accidents excluding drug poisoning, for which mortality was highest among the high poverty group, but approximately equal in all other poverty groups (Supplemental Table). The disparities between high and low poverty groups during 1990 were largest for HIV (62.73 deaths/100,000 population), heart diseases (64.77/100,000 population), and homicide (48.92/100,000 population) (Fig. 2). During 1990–2010, the disparity between high and low poverty groups lessened for all causes of death except diabetes mellitus and hypertension and renal disease (Fig. 2). The largest narrowing of disparities was observed for HIV and homicide.

FIG. 2.

Difference in cause-specific age-adjusted death rates (mortality disparity) between census tracts with the lowest (<10 %) and highest (≥30 %) proportion of the population living below the poverty threshold for selected leading causes of death, New York City, 1990, 2000, and 2010.

Disparities decreased progressively during 1990–2010 for the majority of causes of death, but exceptions occurred. Disparities in heart diseases and chronic lower respiratory diseases decreased from 1990 to 2000, but increased from 2000 to 2010. Conversely, disparities in diabetes mellitus and hypertension and renal disease increased from 1990 to 2000, but decreased from 2000 to 2010 (Fig. 2). The disparities between high and low poverty groups during 2010 were largest for heart diseases (51.52 deaths/100,000 population), diabetes mellitus (19.96/100,000 population), and HIV (19.59/100,000 population) with these three contributing 45 % of the overall mortality disparity between high and low poverty groups.

Excess SES-Related Deaths

There were a total of 5915 excess SES-related deaths in 2010. Of these, 98 were in the 5–<10 % census tract poverty group, 994 were in the 10–<20 % group, 1656 were in the 20–<30 % group, 1647 were in the 30–<40 % group, and 1520 were in the ≥40 % group. The percentage of all deaths that were excess SES-related increased with increasing census tract poverty. Excess SES-related deaths made up 1.0 % of all deaths in the 5–<10 % group, 6.9 % of deaths in the 10–<20 % group, 16.0 % in the 20–<30 % group, 26.0 % in the 30–<40 % group, and 34.8 % in the ≥40 % group.

Discussion

We observed progressively higher all-cause mortality rates with higher census tract poverty at each of the three periods examined. This pattern was apparent within each racial/ethnic group, among both sexes, and for the majority of causes of death. Encouragingly, mortality disparities narrowed between the highest and lowest poverty groups during the 20-year period overall, within racial/ethnic groups, among both sexes, and for the majority of causes of death.

The NYC mortality trends described here differ substantially from national patterns. During 1990, the NYC all-cause AADR was 5 % higher than the US rate (9.89/1000 population versus 9.39/1000 population)8, but dropped to 11.5 % lower than the US rate during 2000 and 19.0 % lower than the US rate during 2010. Moreover, the AADR decreased more in NYC than nationally among both non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks during the 20-year period. Although the National Center for Health Statistics trend data does not include an SES measure8, multiple analyses of national data and one analysis of the Chicago population have revealed increasing disparities in all-cause mortality from 1990 to 2000 by using area-based SES measures.9–12 By contrast, SES-related mortality disparities in NYC decreased from 1990 to 2000 overall and for the majority of leading causes of death. Disparities continued to decrease through 2010, demonstrating a point highlighted by Krieger and colleagues that socioeconomic inequalities in mortality can shrink and need not inevitably rise.10

Multiple explanations and hypotheses exist for the faster decline in mortality rates and socioeconomic mortality disparities in NYC. The HIV/AIDS epidemic had a large impact on overall NYC mortality trends. In 1999, NYC had reported approximately 16 % of all HIV cases in the US despite having less than 3 % of the US Population.13 There were over 4342 HIV deaths in 1990, comprising approximately 6.1 % of total NYC deaths that year. By 2010 the number of HIV deaths had dropped to 802, comprising 1.6 % of total deaths. The large drop in HIV mortality occurred mostly among Hispanics, non-Hispanic blacks, males and the poor (cause-specific race/ethnicity and sex data not shown) and contributed substantially to narrowing disparities in NYC. Similarly, the decline in homicide deaths from 2055 (2.9 % of total deaths) in 1990 to 511 (1.0 % of total deaths) in 2010 occurred among the same population groups and further contributed to the reduction of NYC disparities (data not shown).

Higher than national average in-migration of healthy persons and out-migration of the less healthy might have contributed to a faster apparent mortality decline among US-born persons. However, no studies examining this hypothesis exist. Such studies are needed. Additionally, NYC has a substantial percentage of international immigrants.14 Lower mortality rates among foreign-born persons than those among the US-born could have contributed to the mortality decline.15 However this analysis demonstrated decreases in mortality rates and mortality disparities among both US-born and foreign-born persons. Finally, NYC has long had aggressive public health initiatives to combat major contributors to mortality, with a focus on public policy and prevention efforts among low SES areas of the city. These include intensive tobacco control measures,16 ongoing aggressive identification and treatment of persons infected with HIV,17 monitoring and initiating efforts to reduce obesity and diabetes,18 increased colorectal cancer screening, and outreach to neighborhoods with poor population health indicators through three district public health offices, which conduct activities including delivery of preventive services for hypertension and outreach to limit consumption of sugary drinks.18 These efforts might have contributed to the continued mortality disparity reductions during 2000–2010.

The findings of this analysis have implications for continued efforts to eliminate SES-related health and mortality disparities. The following six causes of death contribute to the majority of the remaining SES-related disparities in 2010: heart disease, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, malignant neoplasms, homicide, and hypertension and renal disease. To continue to reduce these SES-related health inequities, we need to assure that prevention efforts occur among not just the population as a whole, but especially among neighborhoods and communities with poor social and economic conditions for persons who are at highest risk.

Multiple limitations exist that might call for cautious interpretation of these data. First, the data exclude NYC residents who died outside of New York State, which account for approximately 3 % of total NYC deaths.19,20 Second, poverty groups were assigned on the basis of census tract of residence at the time of death and might not reflect decedents’ SES during the majority of their lifetimes. Further, the NYC population has a substantial rate of turnover and immigration, and migration patterns have changed over time.14 For example, the foreign-born population increased as a proportion of the total NYC population from 28 % in 1990 to 37 % in 2010. The foreign-born population also changed with respect to region of origin. From 1990 to 2010, the proportion of foreign-born individuals from Latin America increased from 28 to 32 %, those from Asia also increased from 20 to 28 %, and those from Europe decreased from 24 to 16 %.21 Selective return migration of foreign-born individuals to their country of origin before death may have caused us to underestimate mortality among the foreign-born. An option to select multiple races was added to US Census forms during 2000 and to NYC death certificates during 2003. This caused a slight decrease of race-specific denominators in 2000 and 2010 compared to 1990, and a slight decrease of race-specific numerators in 2010. While this could affect race-specific rates in ways that are uncertain, it is unlikely they would affect the trends reported in this paper. Additionally, race is self-reported on US Census forms and race/ethnicity is reported by a third party on death certificates, therefore the numerator and denominator may represent slightly different populations. Finally, a 2009–2010 quality improvement intervention in eight NYC hospitals that report approximately 13 % of NYC deaths annually reduced the proportion of death certificates reporting heart disease as the cause of death from 69 % to 32 %. This intervention might partially account for the apparent decline in heart disease mortality but would not have affected all-cause mortality rates.22

Summary and Conclusions

We found that census tract-level SES disparities in mortality decreased during 1990–2010 in NYC and that mortality decreased faster than in the USA during this period. However, differences in mortality rates between the highest and lowest poverty census tracts remained substantial for all-cause mortality rates and the majority of leading causes of death. Disparities in diabetes and hypertension and renal disease mortality actually increased. During 2010, an estimated 5900 excess deaths occurred among higher poverty groups, compared with the lowest poverty group. Six causes of death accounted for the majority of SES-related disparities as follows: heart disease, HIV, diabetes, malignant neoplasms, homicide and hypertension and renal disease. Future efforts toward achieving health equity in mortality in NYC should focus on these causes of death and their underlying risk factors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 41 kb)

Footnotes

Difference is statistically significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

Note: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: HHS; 2015. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities. Accessed July 10, 2015

- 2.Karpati A, Kerker B, Mostashari F, et al. Health disparities in New York City. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2004. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/disparities-2004.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2015

- 3.Zimmerman R, Li W, Lee E, et al. Summary of vital statistics, 2013: mortality. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Office of Vital Statistics; 2015. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/data/vs-summary.shtml. Accessed July 10, 2015

- 4.Toprani A, Hadler JL. Selecting and applying a standard area-based socioeconomic status measure for public health data: analysis for New York City. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: Epi Research Report; 2013. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/epiresearch-SES-measure.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- 5.Winkleby MA, Cubbin C. Influence of individual and neighbourhood socioeconomic status on mortality among black, Mexican-American, and white women and men in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:444–52. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Painting a truer picture of U.S. socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:312–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.032482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health, United States, 2013: with special feature on prescription drugs (86–9). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus13.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- 9.Silva A, Whitman S, Margellos H, Ansell D. Evaluating Chicago’s success in reaching the Healthy People 2000 goal of reducing health disparities. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:484–94. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krieger N, Chen JT, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD. Not just smoking and high-tech medicine: socioeconomic inequities in U.S. mortality rates, overall and by race/ethnicity, 1960–2006. Int J Health Serv. 2012;42:293–322. doi: 10.2190/HS.42.2.i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krieger N, Rehkopf DH, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Marcelli E, Kennedy M. The fall and rise of US inequities in premature mortality: 1960–2002. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meara E, Richards S, Cutler D. The gap gets bigger: changes in mortality and life expectancy by education, 1981–2000. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:350–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiasson MA, Berenson L, Li W, et al. Declining HIV/AIDS mortality in New York City. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:59–64. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199905010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NYC Department of City Planning. Current population estimates. New York, NY: The City of New York; 2015. Available at: http://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/data-maps/nyc-population/current-future-populations.page. Accessed March 2, 2016

- 15.Fang J, Madhavan S, Alderman MH. Nativity, race, and mortality: favorable impact of birth outside the United States on mortality in New York City. Human Biol. 1997;69:689–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frieden TR, Mostashari F, Kerker BD, Miller N, Hajat A, Frankel M. Adult tobacco use levels after intensive tobacco control measures: New York City, 2002–2003. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1016–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messeri P, Lee G, Abramson DM, Aidala A, Chiasson MA, Jessop DJ. Antiretroviral therapy and declining AIDS mortality in New York City. Med Care. 2003;41:512–21. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053230.81725.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mortezazadeh C, Miller S, Farley T. Take care New York 2012: a policy for a healthier New York City five-year progress report. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2013. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/tcny/tcny-5year-report2013.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2015

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed mortality file 1979–1998. CDC WONDER online database, compiled from compressed mortality file CMF 1968–1988, Series 20, No. 2A, 2000, and CMF 1989–1998, Series 20, No. 2E, 2003. Hyattsville, MD: CDC; Updated 2015. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd9.html. Accessed July 10, 2015

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed mortality file 1999–2013 on CDC WONDER online database. Compressed mortality file 1999–2013 Series 20 No. 2S, 2014, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Hyattsville, MD: CDC; 2015. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html. Accessed July 7, 2015.

- 21.NYC Department of City Planning. The Newest New Yorkers: characteristics of the city’s foreign-born population, 2013 edition. New York, NY: The City of New York; 2013. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/census/nny2013/nny_2013.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2016

- 22.Madsen A, Thihalolipavan S, Maduro G, et al. An intervention to improve cause-of-death reporting in New York City hospitals, 2009–2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E157. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 41 kb)