Abstract

Aim

To present a review of the contemporary surgical management of skull base tumors.

Background

Over the last two decades, the treatment of skull base tumors has evolved from observation, to partial resection combined with other therapy modalities, to gross total resection and no adjuvant treatment with good surgical results and excellent clinical outcomes.

Materials and methods

The literature review of current surgical strategies and management of skull base tumors was performed and complemented with the experience of Barrow Neurological Institute.

Results

Skull base tumors include meningiomas, pituitary tumors, sellar/parasellar tumors, vestibular and trigeminal schwannomas, esthesioneuroblastomas, chordomas, chondrosarcomas, and metastases. Surgical approaches include the modified orbitozygomatic, pterional, middle fossa, retrosigmoid, far lateral craniotomy, midline suboccipital craniotomy, and a combination of these approaches. The selection of an appropriate surgical approach depends on the characteristics of the patient and the tumor, as well as the experience of the neurosurgeon.

Conclusion

Modern microsurgical techniques, diagnostic imaging, intraoperative neuronavigation, and endoscopic technology have remarkably changed the concept of skull base surgery. These refinements have extended the boundaries of tumor resection with minimal morbidity.

Keywords: Skull base, Skull base surgery, Meningoma, Neuroma, Schwannoma

1. Background

Until the later decades of 20th century, lesions located at the base of the skull were considered inoperable. The introduction of microsurgical techniques, advances in neuroanesthesiology, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), neuronavigation, endoscopy, high-speed drills, and hemostatic agents have dramatically changed the management of these tumors. The main goal of these techniques is to enhance surgical exposure by means of bony resection in order to minimize the need for brain retraction. When brain retraction is necessary, experienced neurosurgeons have replaced fixed retraction with dynamic retraction, thus limiting the risk of injury to underlying brain.1 Patient positioning that enhances gravity retraction, extensive dissection of arachnoid planes, the refinement of microsurgical instrumentation, appropriate selection of operative corridors, and neuronavigation have all been used to improve patient outcomes and reduce morbidities.1, 2, 3, 4 The key principle of skull base surgery is to deconstruct the bony skull base around the brain to create safe apertures to resect deep-seated pathologies.

2. Materials and methods

A review of English-language literature was performed on PubMed on contemporary surgical strategies and management of skull base tumors was performed. This review was complemented with knowledge gained from surgical results and the clinical outcome experience of patients treated at Barrow Neurological Institute.

3. Results

Skull base tumors include meningiomas, pituitary tumors, sellar/parasellar tumors, vestibular and trigeminal schwannomas, esthesioneuroblastomas, chordomas, chondrosarcomas, and metastases. Surgical approaches to the anterior and middle skull base include orbitozygomatic craniotomy or modified orbitozygomatic craniotomy, pterional craniotomy, and middle fossa craniotomy, anterior and posterior transpetrosal approach. Surgical approaches to the posterior fossa include retrosigmoid craniotomy, extended (mastoidectomy, petrosectomy) retrosigmoid craniotomy, far lateral craniotomy, and midline suboccipital craniotomy. The selection of an appropriate surgical approach depends on the characteristics of the tumor (size, type, vascularity, and anatomical relations with the normal brain and/or brainstem) and the experience of the neurosurgeon.

4. Discussion

4.1. General classifications and epidemiology

Skull base tumors can generally be classified as either benign (meningiomas, sellar/parasellar tumors, vestibular and trigeminal schwannomas)5 or malignant (chordoma, chondrosarcoma, metastasis),5 although there is a crossover. The incidence of skull base meningiomas is 2 per 100,000 per year. The incidence of pituitary tumors and vestibular schwannomas is 1 per 100,000 per year.5 Skull base metastases are more common and have an incidence of 18 per 100,000 per year.6 The skull base can be invaded by malignancies originating from the sinonasal tract (esthesioneuroblastoma),7 the nasopharynx (squamous cell carcinoma),8 the oropharynx, the ear region, and the orbit (meningioma, osteoma, rhabdomyosarcoma).5

4.2. Meningiomas

Meningiomas are the most common primary skull base tumors.5 The mainstay of treatment for skull base meningiomas is surgical resection. The surgical approach depends upon the location and size of the tumor. Large tumors may need to be resected in several stages and may require more than one surgical approach. Surgical planning is tailored according to the tumor location and size. Complete surgical resection should be the primary goal. Occasionally, tumors can be firmly attached to the arteries and cranial nerves, making gross total resection impossible. Preoperative angiography and tumor embolization can be useful, but they are rarely necessary.9 The 5-year recurrence rate for a totally resected World Health Organization grade I meningioma is 5%, 40% for grade II, and 50–80% for grade III.

4.3. Anterior and middle skull base meningiomas

Anterior skull base meningiomas include olfactory groove, planum sphenoidale, and tuberculum sellae meningiomas (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).10, 11, 12, 13 The blood supply to these tumors can come from branches of the ethmoidal, meningeal, and ophthalmic arteries. Large tumors can also be supplied by branches of the anterior cerebral artery (A2, frontopolar) (Fig. 2). The olfactory nerves are typically involved, being either displaced or adherent to the tumor. Although preservation of these nerves is challenging, it should be attempted. Even though patients might present as anosmic, return of olfaction after the tumor resection is possible (Fig. 1).14 Surgical approaches to these tumors include unilateral frontal, bilateral frontal, modified orbitozygomatic, and pterional approaches.5 The decision for an approach is made based on the tumor size, extension, size of the frontal sinus, and surgeon's preference. After exposing the lesion, in general, early devascularization of the tumor is preferred. The next step is tumor debulking, which begins with internal debulking and is followed by dissecting the capsule from adjacent structures and folding it in. Reaching the posterior tumor capsule can be the most challenging step, because branches of the anterior cerebral artery might be attached to or encased in the tumor. Even though there is usually an arachnoid plane between the tumor and optic nerve, meticulous dissection is needed to prevent optic nerve damage (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

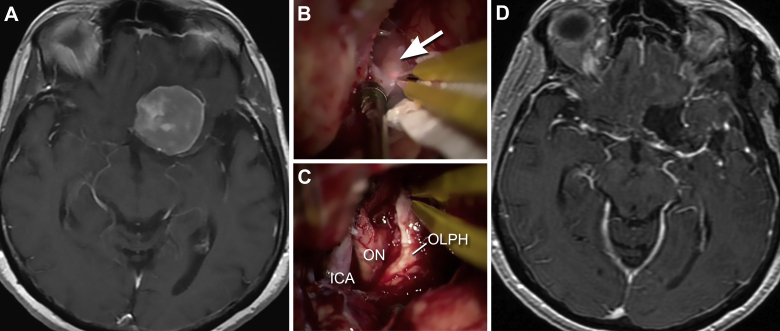

Fig. 1.

Anterior skull base meningioma. A 65-year-old-female presented with left blurry vision. (A) T1-weighted axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium showing a left clinoidal meningioma. The patient underwent a left pterional craniotomy and tumor resection. (B and C) Intraoperative microscopic views of the tumor (arrow) pre- (B) and postresection (C). Even though the olfactory nerve was tightly adhered to the tumor, the nerve (OLPH) is preserved intact. Observe the anatomic relation of the olfactory nerve with the optic nerve (ON) and internal carotid artery (ICA). D, postoperative axial MRI demonstrates complete tumor resection. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.

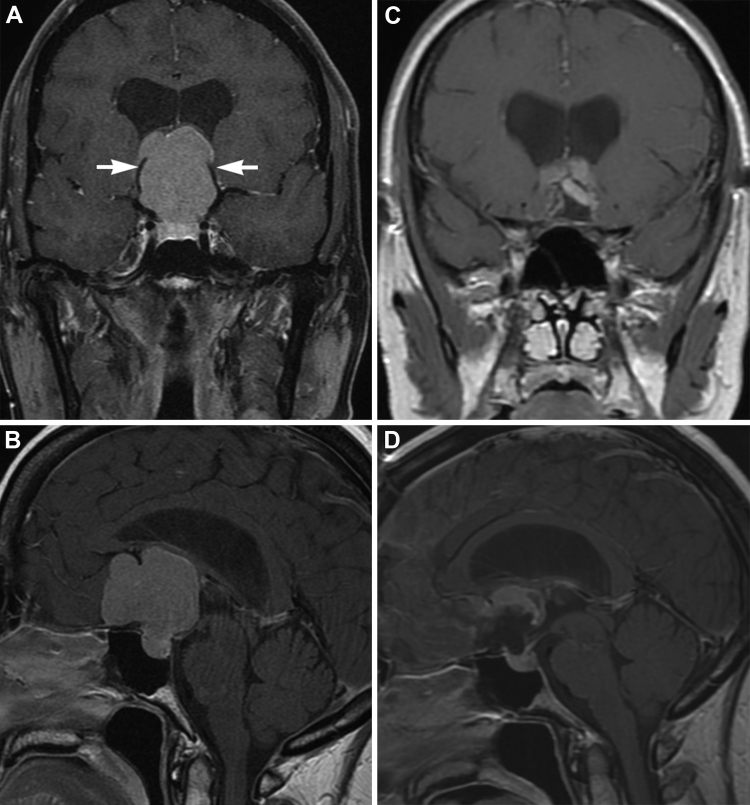

Fig. 2.

Planum sphenoidale/tuberculum sellae meningioma. A 39-year-old-male presented with headaches, visual disturbances, and papilledema. A (coronal) and B (sagittal), T1-weighted MRIs with gadolinium show a large planum sphenoidale/tuberculum sellae meningioma with mass effect on both frontal lobes. The tumor is deforming the third ventricle, causing hydrocephalus. Also notice that both anterior cerebral arteries are stretched and deformed (A, arrows) by the tumor mass. The patient underwent a subfrontal craniotomy and interhemispheric approach for tumor resection. During the microsurgical resection, part of the tumor was extremely adhered to the roof of the third ventricle and fornices. This part of the tumor was not resected. C (coronal) and D (sagittal), postoperative MRIs show almost complete gross total resection. The patient will be managed conservatively with serial imaging. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.

Sphenoid wing meningiomas are typically favorable for surgical resection; however, they have the potential to increase the internal carotid artery (ICA), cavernous sinus, and optic apparatus. Based on location, sphenoid wing meningiomas can be subclassified in spheno-orbital (en plaque or hyperostotic) and globoid meningiomas.15, 16 Sphenoid wing meningiomas can be resected through a pterional or orbitozygomatic craniotomy. Lateral sphenoid wing meningiomas are frequently associated with hyperostosis. In those cases, the craniotomy should be planned to extend beyond the bony infiltration, and extensive skull base drilling is frequently required to completely remove the lesion. Extradural approaches facilitate access to the orbit, middle fossa, the superior and inferior orbital fissures, as well as the cavernous sinus, while minimizing trauma to the brain from retraction.

Ideally, a 1-cm tumor free margin of dura should be removed; however, this is frequently not possible when dealing with skull base lesions. Common complications associated with resection of anterior and middle fossa meningiomas include anosmia (10–20%), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak (10%), and visual disturbances and hemorrhage (5–10%).17

4.4. Posterior skull base meningiomas

Posterior fossa meningiomas comprise 10% of intracranial meningiomas. They are classified by their anatomical origin and include clival, petroclival, cerebellopontine angle (CPA), pineal region, foramen magnum, jugular foramen, and tentorial meningiomas (Fig. 3).1, 18, 19 The diagnosis is generally made radiographically and the preoperative work-up includes MRI and computed tomography. Magnetic resonance venograms can be useful to evaluate venous anatomy, dominance of transverse/sigmoid sinuses, temporal lobe draining patterns, and jugular bulb size. Cerebral angiograms with preoperative embolization can be useful in the management of some meningiomas.9 Due to the limited space within the posterior fossa, adequate bony exposure and early CSF drainage are essential. Hydrocephalus is a common clinical presentation for patients with posterior fossa tumors; therefore, a preoperative ventriculoperitoneal shunt or external ventricular catheter placement is recommended.

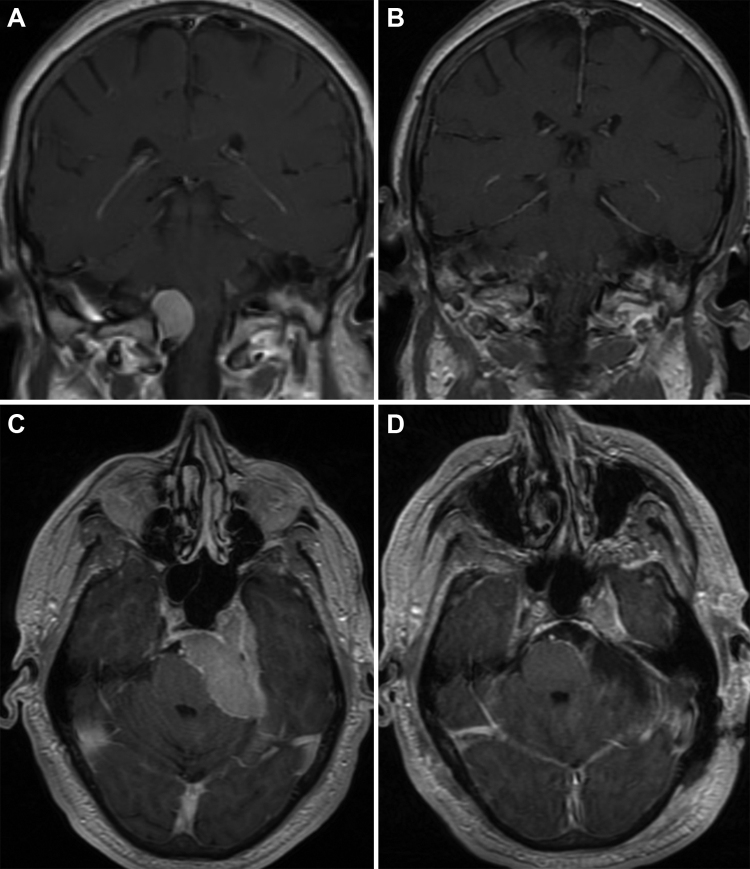

Fig. 3.

Foramen magnum meningioma and petroclival meningioma. A and B, a 53-year-old-male presented with dizziness and vertigo. The T1-weighted coronal MRI (A) with gadolinium shows a right-side lateral foramen magnum meningioma causing mass effect on the brainstem and spinal cord. The patient underwent a right far lateral suboccipital craniotomy with C1 laminectomy and tumor resection. Postoperative coronal MRI (B) demonstrates complete surgical resection. C and D, a 63-year-old male with diplopia, ataxia, and decreased hearing. The T1-weighted axial MRI with gadolinium (C) demonstrates a large left petroclival meningioma causing brainstem compression. Notice that the tumor is infiltrating into the cavernous sinus. The patient underwent a left retrosigmoid craniotomy and tumor resection. The postoperative axial MRI (D) demonstrates gross total resection with excellent decompression of the brainstem. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.

Petroclival meningiomas can extend from the jugular foramen up to the posterior clinoid (Fig. 3C and D). Petroclival meningiomas represent one of the most challenging meningiomas to treat. Different approaches used to access these tumors include the orbitozygomatic, transbasal, subtemporal–transtentorial, transpetrosal (anterior transpetrous approach), and retrosigmoid. Combined approaches are frequently necessary for larger tumors. The combined supra-infratentorial transpetrosal approach exposes the middle and inferior clival region.18, 20

CPA meningiomas are usually treated through a retrosigmoid approach. The blood supply for CPA meningiomas typically originates from the dura of the petrous portion of the temporal bone and sometimes is difficult to interrupt after significant tumor removal. Resection typically begins with internal debulking followed by dissection of the tumor off the cerebellum, brainstem, and cranial nerves. Pitfalls include cranial nerve (V, VII, VIII, IX–XI) and arterial (anterior and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries) injuries.21

Foramen magnum meningiomas account for 4–20% of posterior fossa meningiomas (Fig. 3A and B).19 Surgical approaches include the standard midline suboccipital approach with C1 laminectomy, transoral approach, and far lateral approach. The location of the tumor (anterior vs. posterior) in relation to the spinal cord determines the ideal surgical approach. Preoperative considerations include the relationship of the tumor to the vertebral arteries and their patency, the functional status of the lower cranial nerves, size of the tumor, degree of brainstem/spinal cord compression, and vascularity of the tumor (Fig. 3).19 Complications of posterior fossa meningioma resection include brainstem and cerebellum swelling (sometimes requiring surgical decompression), venous infarction, cranial nerve injury, vertebral artery injury, hydrocephalus, CSF leak, pseudomeningocele, and infection.

4.5. Pituitary adenomas

Pituitary adenomas can be classified as functioning (secreting) or nonfunctioning (nonsecreting) tumors. Lesions ≤10 mm in size are considered microadenomas and those >10 mm are macroadenomas. Symptoms are related to the tumor size and functioning status. Around 97% of microadenomas and 70% of macroadenomas are secreting.22 With the exception of prolactin secreting tumors, the initial treatment for pituitary adenomas is surgical resection. Pharmacological and radiation therapies are sometimes necessary for certain types of tumors. A transsphenoidal approach is most commonly used, except for large tumors with suprasellar extension that require a supratentorial approach. Minimally invasive endoscopic approaches are becoming more commonly used. The advantages of the endoscopic approach include better illumination and improved corner visualization. Results are similar to those with open microscopic surgery.23 Major risks include ICA, optic nerve, and hypothalamic injuries. Other complications include CSF leak, meningitis, intracranial hemorrhage, and nasal sinus infection.

4.6. Sellar and parasellar tumors

Sellar and parasellar lesions include a wide variety of tumors such as pituitary adenomas, craniopharyngiomas, meningiomas, gliomas, neuromas, hemangiomas, germ cell tumors, epidermoid/dermoid cysts, paragangliomas, hamartomas, lymphomas, and metastases. Although transsphenoidal surgery is preferred, transcranial approaches with skull base techniques are often necessary. Indications for transcranial approaches are optic apparatus decompression, tumor extension beyond a transsphenoidal reach (above the level of the middle part of the third ventricle, beyond the midplane of carotid arteries, and higher than the tip of the basilar artery), evidence of a dural tail, and a firm consistency with intimate adherence to the neurovascular structures.

The two classic surgical approaches to this region are the pterional and orbitozygomatic craniotomies. We prefer the modified orbitozygomatic craniotomy because it gives access to the parasellar region, while minimizing soft tissue dissection and bony removal. Removal of the orbital rim and roof facilitates the mobilization of the optic nerve, providing better access through the opticocarotid window. An interhemispheric approach is sometimes necessary when tumors extend high into the third ventricle. A subfrontal approach is useful when the lesion invades the nasal sinuses, orbits, or upper clivus; it also provides access to the third ventricle through the lamina terminalis. Transcranial approaches to the sellar/parasellar region provide better exposure to the microvasculature of the hypothalamus and visual apparatus.

4.7. Craniopharyngiomas

Craniopharyngiomas are benign, extra-axial, intra-arachnoid neoplasms that originate from the craniopharyngeal duct (oral cavity to Rathke's pouch). There are two histological subtypes: adamantinomatous (95% of pediatric cases) and papillary squamous epithelium. Their incidence is about 0.1 per 100,000 per year. The majority of these tumors (>80%) are suprasellar.24 Symptoms are related to endocrine dysfunction (present in 80% of patients) and obstructive hydrocephalus. Complete surgical resection is an important prognostic factor for recurrence. However, total resection is frequently not possible due to the fact that these tumors can tightly adhere to the floor of the third ventricle, hypothalamus, and optic chiasm. Other treatment modalities are often necessary, including radiosurgery, radiation, intracystic chemotherapy, and cystic catheter insertion with intermittent cyst aspiration.

Surgical approaches include pterional, orbitozygomatic, subfrontal/translamina terminalis, interhemispheric transcallosal, and endoscopic variations.25 Our preference is the modified orbitozygomatic craniotomy as it provides access to pre- and retrochiasmatic lesions, and areas above and below the diaphragm sellae. The lamina terminalis is easily opened to provide access to the third ventricle. For large midline tumors with extension into the third ventricle and foramen of Monro, an interhemispheric transcallosal approach is necessary. Gross total resection rates vary from 50% to 90%. The rates of gross total resection are higher in children than in adults. Recurrence rates after gross total resection vary from 0% to 50% at 10 years. Postoperative morbidity has been reported to be 1.7–5.4%. Visual decline after aggressive resection occurs in 4% to 30% of patients. Endocrinopathies are frequent postoperatively, with diabetes insipidus, either transient or permanent, being the most common.26

4.8. Vestibular schwannoma

Vestibular schwannomas have an incidence of 1 per 100,000 per year; this rate has increased during recent years due to the routine use of brain MRI. The growth rate of these tumors usually guides decisions on treatment versus observation. Growth rates vary from 0.4 to 2.4 mm/yr. Typically, extrameatal tumors have faster growth rates than intrameatal lesions.27, 28, 29 Cystic tumors and those related to neurofibromatosis type 2 also tend to have a more aggressive course and are associated with a more rapid neurological deterioration. Vestibular schwannomas are the most common tumors diagnosed in the cerebellopontine angle (70–80%). MRI with a specific internal auditory canal protocol provides anatomical information necessary for surgical planning and should be obtained routinely (Fig. 4). The treatment goals and surgical approach should be individualized based on characteristics of the patient (age, hearing status) and the tumor (size, cystic).30

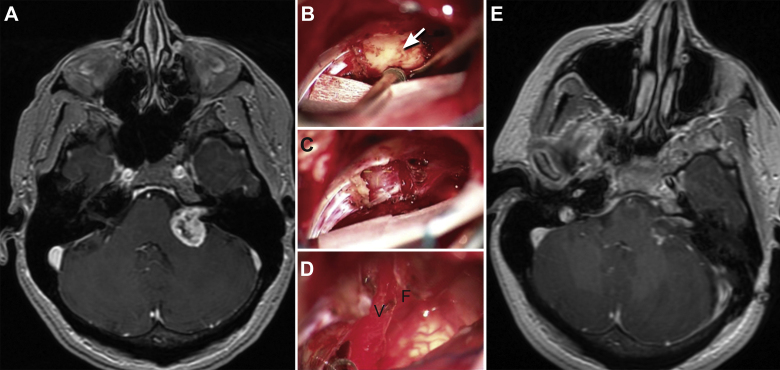

Fig. 4.

Vestibular schwannoma. A 49-year-old-female presented with left side decreased hearing. (A) T1-weighted axial MRI with gadolinium shows a cystic cerebellopontine tumor causing mass effect on the cerebellum and brainstem. The patient underwent a left retrosigmoid craniotomy and tumor resection. (B–D) Intraoperative microscopic images show the tumor before resection (arrow) (B), after drilling the internal auditory canal (C), and after complete resection (D). Notice that the vestibular (V) and facial (F) cranial nerves were preserved. E, postoperative axial MRI demonstrates gross total resection. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.

Three main surgical approaches are used for treating vestibular schwannomas: retrosigmoid, middle fossa, and translabyrinthine.27, 28, 29 The retrosigmoid approach is familiar to neurosurgeons and can be used to address large tumors compressing the brainstem as well as small intracanalicular tumors. It gives an extraordinary view of the cranial nerves and main vasculature. After accessing the posterior fossa, the first step is to open the cisterna magna and drain CSF. This step is crucial in any CPA surgery to reduce cerebellar retraction and facilitate arachnoid dissection and tumor resection. Another critical step during resection of acoustic neuromas is the identification of the seventh and eighth cranial nerves. The facial nerve is typically found anteriorly in the middle third of the capsule.27 Brainstem auditor evoked responses (BAERs) and a hand-held nerve stimulator are routinely ordered for these cases. The posterior wall of the internal auditory canal is drilled off to expose the intracanalicular portion of the tumor, when necessary, to achieve a gross total resection (Fig. 4), and also for early identification of the facial nerve. The translabyrinthine approach has the advantage of early facial nerve identification, but is not appropriate if hearing preservation is the goal. Exposure requires a mastoidectomy and labyrinthectomy with skeletonization of the facial nerve. Usually, an arachnoid plane is found between the nerve and the tumor. Large tumors are debulked first and then dissected off the nerve. The facial nerve is most frequently found along the anterior margin of the tumor or splayed over the top of the tumor. With this approach, the medial aspect of the tumor attached to the brainstem is the most challenging portion of the dissection. The middle cranial fossa approach is indicated for small laterally located intracanalicular tumors when hearing preservation is the goal.28, 31 Common complications may include CSF leak (4–27%), hearing loss, facial nerve palsy, lower cranial nerve palsy, cerebellar contusion, air embolism (if using a sitting position), and infection. Radiosurgery is used for the management of small tumors (usually less than 2 cms) or residual tumor.

4.9. Trigeminal schwannomas

Trigeminal schwannomas are rare benign skull base tumors. They account for 0.07% to 0.36% of all intracranial tumors. Trigeminal schwannomas commonly originate from the Gasserian ganglion, have a dumbbell shape, and can extend into the middle fossa (most commonly), posterior cranial fossa, and the extracranial space. These tumors have been classified based on their anatomic extension and shape into type A (middle fossa), type B (posterior fossa), type C (dumbbell), and type D (extracranial).32, 33

Surgical resection remains the definitive treatment, and the location of the tumor dictates the surgical approach. Type A tumors can be approached through a pterional or orbitozygomatic extradural or transsylvian exposure and via a subtemporal intradural approach. Type B tumors are predominantly located within the CPA and a classic retrosigmoid craniotomy exposes the tumor; however, if the tumor extends into the middle fossa, a transpetrosal or combined transpetrosal approach is necessary. Type C tumors are more challenging and multiple approaches are often necessary. Orbitozygomatic, petrosal, and combinations of these two approaches have resulted in satisfactory patient outcomes. We have used the modified orbitozygomatic craniotomy and found that it provides excellent access to the posterior fossa through Meckel's cave. Type D tumors extend inferiorly into the infratemporal fossa and cranial foramina, requiring a preauricular–infratemporal approach. Patient outcomes have dramatically changed with modern neurosurgical techniques. Gross total resections are achieved in 75–100% of reported cases.34, 35

4.10. Cavernous sinus tumors

Surgical approaches to the cavernous sinus, once called “no man's land” have changed dramatically with the modern era of microneurosurgery. Primary cavernous sinus meningiomas are rare (<3% of all meningiomas) and attempts at subtotal or total resection of these lesions increase the likelihood of iatrogenic worsening or new cranial nerve deficits. Our current practice is to consider resection for extracavernous portions of the tumor, or to biopsy intracavernous tumors, if a tissue diagnosis is required. Depending on the tumor location within the cavernous sinus, two different approaches can be used. The anterior cavernous sinus can be approached through a temporopolar extradural or frontotemporal (modified orbitozygomatic) intradural approach, and the posterior cavernous sinus can be accessed through an anterior transpetrosal approach. For skull base meningiomas with cavernous sinus involvement, tumor control is achievable with extra cavernous resection alone in up to 90% of cases. Patients with atypical and more aggressive tumors may require radical resections with ICA sacrifice and cerebral revascularization.36, 37 Adjuvant therapy with stereotactic radiosurgery has shown good control rates for skull base meningiomas and can be considered in patients with tumor progression whose tumors are not amenable to surgical resection. Radiosurgery, including heavy charged particle irradiation, play an important role as an adjuvant to the management of cavernous sinus lesion, however it is beyond the scope of this work.

4.11. Glomus tumors (paraglanglioma)

Glomus tumors (paraglangliomas) are rare, with an incidence of 1 to 3 cases per million people and a strong female predominance (6:1). These tumors are indolent, with a slow, locally invasive growth pattern. Clinical symptoms are related to the location of the tumor. The temporal bone, middle ear, jugular foramen, hypoglossal canal, and clivus are commonly involved. Less commonly, these lesions can extend into the cavernous sinus and sellar/parasellar region or metastasize (pulmonary and gastrointestinal tract). Findings on computed tomography of the head include bony destruction/remodeling (enlarged jugular foramen and erosion of petroclival junction). These tumors are very vascular lesions that can be supplied by the ascending pharyngeal (posterior meningeal branches), internal maxillary, occipital, and internal carotid arteries. The ideal management for resectable tumors is embolization9 followed by surgical resection.38 That these are primarily extradural tumors helps to facilitate a complete surgical resection. The lateral skull base approach involves an extensive craniocervical dissection, a complete mastoidectomy, and C1 laminectomy with ligation of the sigmoid sinus. Major morbidities include facial paralysis, hearing loss, and lower cranial nerve injuries. The infratemporal fossa approach extends rostrally into the ear canal to expose the ICA up to the cavernous sinus.39 Gross total resection has been reported in up to 90% of cases. However, functional recovery is rare and morbidity is significant. Morbidity is largely due to facial palsy, hearing loss, and lower cranial nerve palsies.40

4.12. Chordomas and chondrosarcomas

Chordomas and chondrosarcomas are rare, benign tumors that originate from cells of the notochord. These slow-growing tumors are locally destructive (Fig. 5). The incidence is 0.08 per 100,000 per year, being most common in white males. Radiographically, chordomas and chondrosarcomas are indistinguishable except for the location. Chondrosarcomas arise from a more paramedian location (Fig. 5D–F), whereas chordomas originate in the midline (Fig. 5A–C). Both tumors can grow into the nasopharynx, orbits, and sella. Local bony destruction and invasion can make oncologic excision very difficult.41 Because these tumors are relatively insensitive to radiation and chemotherapy, surgery is the primary treatment modality.

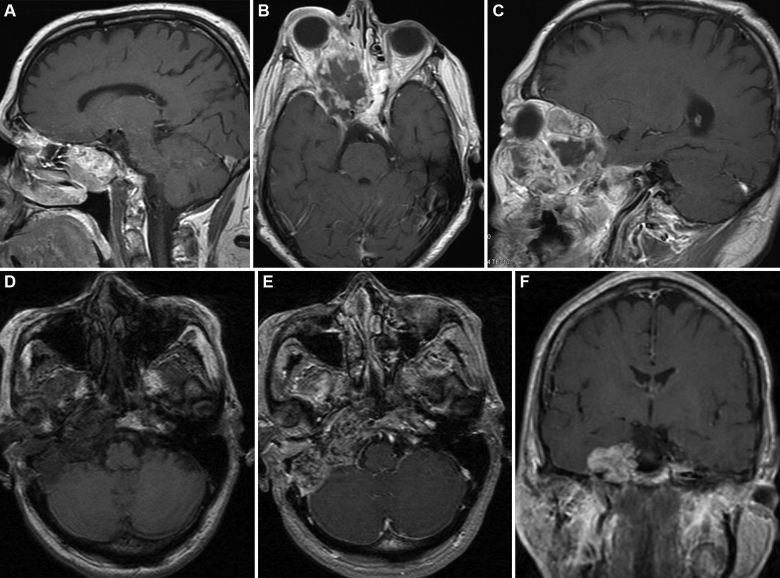

Fig. 5.

Chordoma and chondrosarcoma. (A–C) A 67-year-old-male with a chordoma that was initially diagnosed at the age of 55 (A, sagittal MRI). He underwent multiple resections for tumor recurrences. Twelve years after the original diagnosis and 2 years after “complete” surgical resection, he presented with a large, infiltrative recurrence (B and C, axial and coronal MRIs, respectively). Notice the tumor extension into the ethmoid sinuses, cavernous sinus and right orbit. (D–F) 37-year-old-female with progressive right cranial nerve deficits (III, VI, VII and VIII) was found to have a skull base chondrosarcoma. Axial MRI pre- (D) and axial and coronal MRIs postcontrast (E and F) show the skull base mass lesion. These lesions required repeated extradural middle cranial fossa approaches for tumor control. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.

The appropriate surgical approach is based on size and location. Midline upper clival tumors are approached anteriorly via transphenoidal, subfrontal, transpharyngeal transpalatal approaches; lateral clival and paraclinoid tumors can be accessed through an orbitozygomatic approach; and posterior or lateral extension can require a middle fossa or transpetrosal approach.42 Tumors at the lower clivus or foramen magnum often require an oral or a far lateral approach. Two or more approaches are sometimes necessary to treat a single tumor. The core of these tumors usually has a soft gelatinous consistency that can readily be aspirated. The fibrous outer layer is classically more difficult to resect because it may be firmly attached to the brainstem and neurovascular structures. Chordomas tend to invade into cancellous bone. Local recurrence is responsible for the greatest amount of morbidity and mortality in these patients (Fig. 5A–C).43 Chondrosarcomas are much less aggressive and these patients have a higher rate of recurrence-free survival.41

4.13. Esthesioneuroblastoma

Esthesioneuroblastoma is a rare tumor that arises from the olfactory epithelium and can extend into the skull base, paranasal sinuses, and orbits (Fig. 6). Esthesioneuroblastomas account for up to 2–3% of all intranasal neoplasms. A multidisciplinary team approach, including a neurosurgeon, ophthalmologist, otolaryngologist, and medical and radiation oncologists, is usually required.44, 45 Surgical resection is the mainstay of therapy for these tumors. Gross total resection results in a statistically significant improvement in outcome. Neoadjuvant radiation and chemotherapy, administered before surgery, have been used to decrease tumor mass and minimize local tumor dissemination and distant metastasis during surgery.44, 45

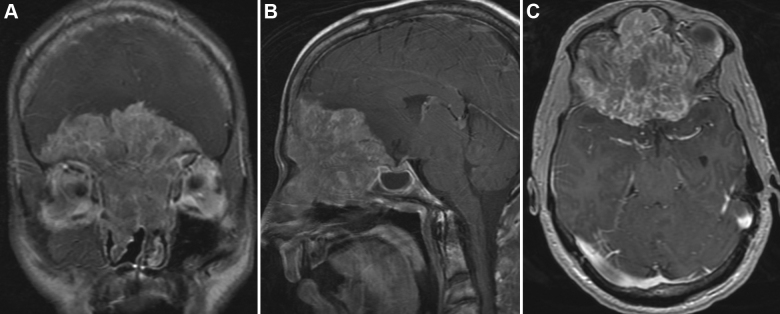

Fig. 6.

Esthesioneuroblastoma. A 25-year-old male presented with headaches, anosmia, and seizures. (A–C) Coronal, sagittal, and axial (respectively) T1-weighted MRIs with gadolinium demonstrate a large enhancing mass extending down into the ethmoidal sinuses and nasal cavity and extending up causing mass effect on both frontal lobes. The large mass occupies the entire anterior cranial base. Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.

The surgical approach most commonly used is a bifrontal craniotomy through a bicoronal incision with pericranial flap preservation for skull base reconstruction. The bifrontal craniotomy is accompanied with exenteration of the frontal and ethmoidal sinuses if necessary. Skull base osteotomies have to be carefully planned so that they extend beyond the tumor margins. Frozen specimens are examined intraoperatively to verify tumor free margins. The most common complications include CSF leak, intracranial infection, and hemorrhage. Meticulous skull base reconstruction is mandatory. Dead spaces are voided and obliterated with free fat grafts and fibrin glue. With current management, patients have 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year disease-free survival rates of 97%, 83%, and 62.8%, respectively.46 Recurrence is common (14%) even after gross total resection with a mean follow-up of 8 years, and recurrence is most commonly found at 4 years.46, 47 Brain, lung, and bone are the most common sites of distal metastases.48

4.14. Craniofacial malignancies

Sinonasal malignancies account for most of the craniofacial malignancies. They account for less than 3% of the upper aerodigestive tract. Around 60–70% arise from the maxillary sinus, 10–15% from the ethmoid sinuses, the remaining from the frontal and sphenoid ones.49 Sinonasal malignancies can grow to a considerable size before developing any concerns, hence, late presentation is a common occurrence. Craniofacial malignancies include squamous cell carcinoma which is the most common. It erodes through the bony margins of the nose and sinuses and invades the orbit, ethmoidal roof and cribriform plate into the anterior skull base. Best treatment results from chemoradiotherapy followed by aggressive surgery. A 5-year survival is 30%.50, 51 Adenocarcinoma is related to wood dust exposure. Treatment is surgical. A 5-year survival is around 45%.52 Adenoid cyst carcinoma is a slow-growing tumor but has the capacity for widespread local dissemination by perineuronal spread. Olfactory neuroblastoma involves the cribriform plate and the olfactory bulb. The 5-year survival rates are 80% with complete surgical resection. Anaplastic carcinoma, sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, and malignant melanoma has the worst prognosis.53, 54, 55 Management is best accomplished by a multidisciplinary team. Details of the surgical approaches are out of the scope of this article but some principles are worth mentioning and they include: adequate exposure and oncological resection of the tumor, minimal or no brain retraction, watertight dural closure using dural patch (fascia lata, pericranial flap) if necessary, meticulous reconstruction of the skull base and optimal esthetic outcome.

4.15. Skull base metastasis

Cranial base metastasis occurs in approximately 4% of cancer patients.56 The most common primary tumors are breast, lung, renal, and prostate.6, 57 Indications for surgical resection are to obtain a pathological diagnosis in cases of unknown primary tumors, to provide symptomatic relief, decrease mass effect, and remove solitary metastasis.56

The surgical approach depends on the location of the tumor. A recent analysis of patients with skull base metastases showed that the anterior cranial fossa was the most common location (51.8%) followed by middle fossa. Currently, radiotherapy/stereotactic radiosurgery are the first line of treatment for skull base metastases, particularly for tumors sensitive to radiation (lung, breast, prostate). The main limitations of radiation therapy are related to the size of the lesion and the proximity to critical structures, such as the optic nerve and brainstem. On the other hand, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and most sarcomas are relatively radiotherapy resistant and surgery should be considered. The ideal candidate for surgery is a patient with a well-controlled systematic disease, good functional status, and a relatively long expected survival.6, 56, 57

5. Conclusion

The contemporary surgical management of skull base tumors offers satisfactory surgical results and good to excellent clinical outcomes. Modern microsurgical techniques, diagnostic imaging, intraoperative neuronavigation, and endoscopic technology have remarkably changed the concept of skull base surgery. These refinements have extended the boundaries of tumor resection and obviated the need for adjuvant therapies in some patients with benign tumors. In some cases, the main goal of skull base surgery is not the complete removal of the lesion, but the improvement of quality of life and the prolongation of the disease free survival time. For patients with skull base malignancies, a multidisciplinary approach is mandatory to plan treatments that incorporate surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy to maximize the patients’ outcomes.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

References

- 1.Spetzler R.F., Sanai N. The quiet revolution: retractorless surgery for complex vascular and skull base lesions. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(2):291–300. doi: 10.3171/2011.8.JNS101896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waring A.J., Housworth C.M., Voorhies R.M., Douglas J.R., Walker C.F., Connolly S.E. A prototype retractor system designed to minimize ischemic brain retractor injury: initial observations. Surg Neurol. 1990;34(3):139–143. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(90)90062-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguchi M., Jadhav V., Obenaus A., Colohan A., Zhang J.H. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition attenuates brain edema in an in vivo model of surgically induced brain injury. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(5):1067–1075. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303203.07866.18. discussion 1075–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackeith S.A., Kerr R.S., Milford C.A. Trends in acoustic neuroma management: a 20-year review of the oxford skull base clinic. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2013;74(4):194–200. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1342919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ammirati M.Z.H. Oncology. In: Brem H., editor. vol. 2. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2011. (Youmans neurological surgery). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laigle-Donadey F., Taillibert S., Martin-Duverneuil N., Hildebrand J., Delattre J.Y. Skull-base metastases. J Neurooncol. 2005;75(1):63–69. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-8099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollen T.R., Morris C.G., Kirwan J.M. Esthesioneuroblastoma of the nasal cavity. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31829b5631. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobinskas A.M., Wiesenfeld D., Chandu A. Influence of the site of origin on the outcome of squamous cell carcinoma of the maxilla-oral versus sinus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Feb 2014;43(2):137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rangel-Castilla L., Shah A.H., Klucznik R.P., Diaz O.M. Preoperative Onyx embolization of hypervascular head, neck, and spinal tumors: experience with 100 consecutive cases from a single tertiary center. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6(1):51–56. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margalit N., Shahar T., Barkay G. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: surgical technique, visual outcome, and prognostic factors in 51 cases. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2013;74(4):247–258. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1342920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mielke D., Mayfrank L., Psychogios M.N., Rohde V. The anterior interhemispheric approach – a safe and effective approach to anterior skull base lesions. Acta Neurochir. 2014;156(4):689–696. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1972-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bitter A.D., Stavrinou L.C., Ntoulias G. The role of the pterional approach in the surgical treatment of olfactory groove meningiomas: a 20-year experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2013;74(2):97–102. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avci E., Akture E., Seckin H. Level I to III craniofacial approaches based on Barrow classification for treatment of skull base meningiomas: surgical technique, microsurgical anatomy, and case illustrations. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;30(5):E5. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.FOCUS1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber M., Vishteh A.G., Spetzler R.F. Return of olfaction after gross total resection of an olfactory groove meningioma: case report. Skull Base Surg. 1998;8(4):229–231. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forster M.T., Daneshvar K., Senft C., Seifert V., Marquardt G. Sphenoorbital meningiomas: surgical management and outcome. Neurol Res. 2014;36(8):695–700. doi: 10.1179/1743132814Y.0000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talacchi A., De Carlo A., D’Agostino A., Nocini P. Surgical management of ocular symptoms in spheno-orbital meningiomas: is orbital reconstruction really necessary? Neurosurg Rev. 2014;37(2):301–310. doi: 10.1007/s10143-014-0517-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aguiar P.H., Tahara A., Almeida A.N. Olfactory groove meningiomas: approaches and complications. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(9):1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bambakidis N.C., Kakarla U.K., Kim L.J. Evolution of surgical approaches in the treatment of petroclival meningiomas: a retrospective review. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(5 Suppl. 2):202–209. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303218.61230.39. discussion 209–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.David C.A., Spetzler R.F. Foramen magnum meningiomas. Clin Neurosurg. 1997;44:467–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho C.W., Al-Mefty O. Combined petrosal approach to petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(3):708–716. discussion 716–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cikla U., Kujoth G.C., Baskaya M.K. A stepwise illustration of the retrosigmoid approach for resection of a cerebellopontine meningioma. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;36(Suppl. 1):1. doi: 10.3171/2014.V1.FOCUS13445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lake M.G., Krook L.S., Cruz S.V. Pituitary adenomas: an overview. Am Fam Phys. 2013;88(5):319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodhinayake I., Ottenhausen M., Mooney M.A. Results and risk factors for recurrence following endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;119:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller H.L. Craniopharyngioma. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(3):513–543. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuo T., Kamada K., Izumo T., Nagata I. Unilateral Basal Interhemispheric Approach through the sphenoid sinus to retrochiasmatic and intrasellar craniopharyngiomas: surgical technique and results. World Neurosurg. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.02.005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerganov V., Metwali H., Samii A., Fahlbusch R., Samii M. Microsurgical resection of extensive craniopharyngiomas using a frontolateral approach: operative technique and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(2):559–570. doi: 10.3171/2013.9.JNS122133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samii M., Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): the facial nerve – preservation and restitution of function. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(4):684–694. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199704000-00006. discussion 694–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samii M., Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): hearing function in 1000 tumor resections. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(2):248–260. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199702000-00005. discussion 260–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samii M., Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): surgical management and results with an emphasis on complications and how to avoid them. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(1):11–21. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199701000-00002. discussion 21–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson D.E., Leonetti J., Wind J.J., Cribari D., Fahey K. Resection of large vestibular schwannomas: facial nerve preservation in the context of surgical approach and patient-assessed outcome. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(4):643–649. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.4.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betchen S.A., Walsh J., Post K.D. Long-term hearing preservation after surgery for vestibular schwannoma. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(1):6–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.1.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jefferson G. The trigeminal neurinomas with some remarks on malignant invasion of the gasserian ganglion. Clin Neurosurg. 1953;1:11–54. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/1.cn_suppl_1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day J.D., Fukushima T. The surgical management of trigeminal neuromas. Neurosurgery. 1998;42(2):233–240. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199802000-00015. discussion 240–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L.F., Yang Y., Yu X.G. Operative management of trigeminal neuromas: an analysis of a surgical experience with 55 cases. Acta Neurochir. 2014;156:1105–1114. doi: 10.1007/s00701-014-2051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wanibuchi M., Fukushima T., Zomordi A.R., Nonaka Y., Friedman A.H. Trigeminal schwannomas: skull base approaches and operative results in 105 patients. Neurosurgery. Mar 2012;70(1 Suppl. Operative):132–143. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31822efb21. discussion 143–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalani M.Y., Kalb S., Martirosyan N.L. Cerebral revascularization and carotid artery resection at the skull base for treatment of advanced head and neck malignancies. J Neurosurg. 2013;118(3):637–642. doi: 10.3171/2012.9.JNS12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sindou M., Wydh E., Jouanneau E., Nebbal M., Lieutaud T. Long-term follow-up of meningiomas of the cavernous sinus after surgical treatment alone. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(5):937–944. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/11/0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Mefty O., Teixeira A. Complex tumors of the glomus jugulare: criteria, treatment, and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(6):1356–1366. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.6.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisch U. Infratemporal fossa approach for lesions in the temporal bone and base of the skull. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1984;34:254–266. doi: 10.1159/000409856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sivalingam S., Konishi M., Shin S.H., Lope Ahmed R.A., Piazza P., Sanna M. Surgical management of tympanojugular paragangliomas with intradural extension, with a proposed revision of the Fisch classification. Audiol Neurootol. 2012;17(4):243–255. doi: 10.1159/000338418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almefty K., Pravdenkova S., Colli B.O., Al-Mefty O., Gokden M. Chordoma and chondrosarcoma: similar, but quite different, skull base tumors. Cancer. 2007;110(11):2457–2467. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horgan M.A., Anderson G.J., Kellogg J.X. Classification and quantification of the petrosal approach to the petroclival region. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(1):108–112. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.1.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzortzidis F., Elahi F., Wright D., Natarajan S.K., Sekhar L.N. Patient outcome at long-term follow-up after aggressive microsurgical resection of cranial base chordomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(2):230–237. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000223441.51012.9D. discussion 230–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ow T.J., Bell D., Kupferman M.E., Demonte F., Hanna E.Y. Esthesioneuroblastoma. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2013;24(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ow T.J., Hanna E.Y., Roberts D.B. Optimization of long-term outcomes for patients with esthesioneuroblastoma. Head Neck. 2014;36(4):524–530. doi: 10.1002/hed.23327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herr M.W., Sethi R.K., Meier J.C. Esthesioneuroblastoma: an update on the massachusetts eye and ear infirmary and massachusetts general hospital experience with craniofacial resection, proton beam radiation, and chemotherapy. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2014;75(1):58–64. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rimmer J., Lund V.J., Beale T., Wei W.I., Howard D. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a 35-year experience and suggested follow-up protocol. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(7):1542–1549. doi: 10.1002/lary.24562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diaz E.M., Jr., Johnigan R.H., 3rd, Pero C. Olfactory neuroblastoma: the 22-year experience at one comprehensive cancer center. Head Neck. 2005;27(2):138–149. doi: 10.1002/hed.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taghi A., Ali A., Clarke P. Craniofacial resection and its role in the management of sinonasal malignancies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12(9):1169–1176. doi: 10.1586/era.12.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jakobsen M.H., Larsen S.K., Kirkegaard J., Hansen H.S. Cancer of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: prognosis and outcome of treatment. Acta Oncol. 1997;36(1):27–31. doi: 10.3109/02841869709100727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lund V.J., Howard D.J., Wei W.I., Cheesman A.D. Craniofacial resection for tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses – a 17-year experience. Head Neck. 1998;20(2):97–105. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199803)20:2<97::aid-hed1>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knegt P.P., Ah-See K.W., vd Velden L.A., Kerrebijn J. Adenocarcinoma of the ethmoidal sinus complex: surgical debulking and topical fluorouracil may be the optimal treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127(2):141–146. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Helliwell T.R., Yeoh L.H., Stell P.M. Anaplastic carcinoma of the nose and paranasal sinuses: light microscopy, immunohistochemistry and clinical correlation. Cancer. 1986;58(9):2038–2045. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861101)58:9<2038::aid-cncr2820580914>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uchida D., Shirato H., Onimaru R. Long-term results of ethmoid squamous cell or undifferentiated carcinoma treated with radiotherapy with or without surgery. Cancer J. 2005;11(2):152–156. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lund V.J., Howard D.J., Harding L., Wei W.I. Management options and survival in malignant melanoma of the sinonasal mucosa. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(2 Pt 1):208–211. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199902000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chamoun R.B., Suki D., DeMonte F. Surgical management of cranial base metastases. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(4):802–809. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318236a700. discussion 809–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenberg H.S., Deck M.D., Vikram B., Chu F.C., Posner J.B. Metastasis to the base of the skull: clinical findings in 43 patients. Neurology. 1981;31(5):530–537. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.5.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]