Abstract

Neurosarcoidosis is a rare diagnosis, and it is also unusual for a patient with sarcoidosis to present solely with neurologic disease. However, CNS involvement can be the first manifestation of disease in 50% of patients. Thus, it is an important diagnostic consideration in patients presenting with ambiguous nervous-system lesions, particularly in the population most often affected by sarcoidosis: young African-Americans. We report a case of a 32-year-old African-American male with spinal sarcoidosis presenting as bilateral upper-extremity and upper-trunk parasthesias secondary to an intramedullary spinal lesion.

Case report

A 32-year-old African-American male with no past history of head or neck trauma presented with a one-year history of paresthesias in both arms radiating from his neck, with occasional radiation to his upper trunk. The symptoms were more pronounced in his left 4th and 5th digits. On exam, the patient had a mild decrease in sensation in his left 4th and 5th digits, which did not split the ring finger. His symptoms were reproducible with head flexion. Recent plain films of his cervical spine had not shown osseous abnormalities or abnormality of his curvature.

A cervical MRI showed a 1cm enhancing lesion at the C5-C6 level on the postcontrast T1-weighted scan, with associated cord edema and cord expansion (Fig. 1). The lesion was isointense to slightly hypointense to the cord on the precontrast T1-weighted images. The cord edema extended approximately 5.5cm from C4 to C7. On the T2-weighted images, the lesion had central low-signal intensity with peripheral hyperintensity (Fig. 2A). The T2 scans further revealed a proximal hyperintense syrinx, likely postobstructive, extending 1.8cm from C4-C5 (Fig. 2B). The presence of the syrinx increased concern for a space-occupying lesion such as an ependymoma or astrocytoma. Based on these results, brain, thoracic, and lumbar spine images were obtained. The lumbar imaging was unremarkable, and the brain MRI showed nonspecific changes. The thoracic image confirmed the presence of another syrinx distal to the lesion extending from T5-T10.

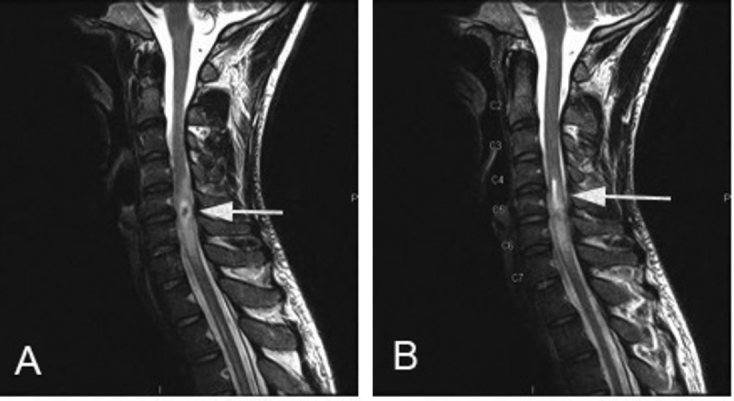

Figure 1.

32-year-old male with intramedullary spinal neurosarcoidosis. Postcontrast T1-weighted images revealed a 1cm enhancing lesion (arrow) at C5-C6 with associated cord edema and expansion.

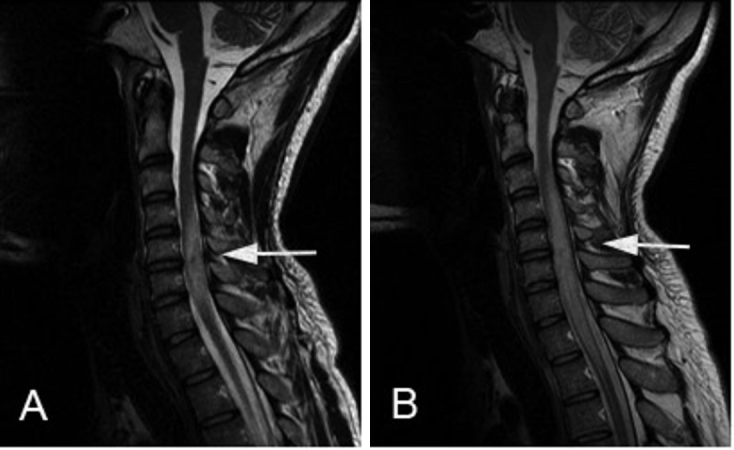

Figure 2.

32-year-old male with intramedullary spinal neurosarcoidosis. The lesion (arrow) had low signal intensity centrally with peripheral hyperintensity on T2-weighted images (A). A hyperintense syrinx, extending 1.8cm, lies proximal to the lesion (arrow) (B).

At this point, the patient was started on dexamethasone (Decadron), which he discontinued shortly after a few weeks due to intractable hiccups, and was thereafter referred to a tertiary hospital for neurosurgical evaluation. He had presented to this center several months earlier for a syncopal episode in the setting of heavy alcohol use. During that hospital visit, a chest CTA showed bilateral and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The chest CTA results increased suspicion that his spinal lesion could represent neurosarcoidosis. PET CT imaging was therefore obtained to further characterize the chest CT abnormalities; it showed mildly PET-avid hilar and paratracheal lymphadenopathy. A lumbar puncture was not performed due to concern about the cord edema, but a serum ACE level was mildly elevated at 59 (normal, 7-46).

The patient was lost to followup for the next ten months largely because he had noted symptom improvement. When he presented again, the paresthesias had worsened. A repeated cervical MRI revealed enlargement of the enhancing mass at the C5-C6 level (Fig. 3A). The patient was started on a trial of 60mg prednisone daily. At his followup appointment six weeks later, the patient reported that he had stopped taking the prednisone after approximately four weeks. The reasons for stopping the medication are unclear; however, he did note improvement in his left-hand paresthesias while taking the prednisone. At this followup, he reported increasing neck pain aggravated with head turning. Repeated imaging revealed further enlargement of the mass and increased cord edema (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

32-year-old male with intramedullary spinal neurosarcoidosis. T2-weighted images demonstrated increasing cord expansion and edema (A). Imaging six weeks later demonstrated markedly increased cord edema and cord expansion extending from C2 to T2 and associated with a syrinx in the upper thoracic spinal cord (B).

Given the rate of growth of the mass, the concern for tumor was quite high, and surgical intervention with biopsy and cord decompression was performed. The surgical biopsy demonstrated noncaseating granulomas, confirming the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. The patient was managed with prednisone but failed several attempts at weaning, citing exacerbations of numbness which correlated with the increased edema noted on MRI.

Two years after his operation, the patient continues to take immunosuppressive medication, and is currently taking mycophenolate (CellCept) and adalimumab (Humira). His prednisone is being slowly decreased. Cervical MRI scans continue to demonstrate some signal abnormality; however, the intensity of the enhancement is markedly decreased, as are the caliber of the cord and surrounding edema (Fig. 4A and 4B). Imaging of the thoracic spine has demonstrated resolution of the syrinx that was seen before surgery.

Figure 4.

32-year-old male with intramedullary spinal neurosarcoidosis. Postoperative MRI scans with laminectomies from C4-C7. The postcontrast T1-weighted image showed decreased enhancement of the lesion (arrow) at C5-C6 compared to pre-operative scans (A). The T2-weighted image showed marked decrease in hyperintensity (arrow) compared to pre-operative scans. There was only mild cord enlargement at the level of the lesion, and the edema extended only from C4-C7, compared to C2-T2 before surgery (B).

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem, noncaseous, granulomatous disease of unknown etiology, typically affecting the lungs and mediastinal lymph nodes. It can affect patients of any age, gender, or ethnic background, but the prototypical patient is an African-American female in the third or fourth decade of life. Clinical involvement of the nervous system occurs in only 5% of patients with sarcoidosis (1), though about 15-25% of patients with sarcoidosis have CNS involvement on autopsy (2, 3). Approximately 50% of patients, like the patient in this case report, present clinically without an initial sarcoidosis diagnosis (2), making it imperative for physicians to consider neurosarcoidosis in the differential.

The most common sarcoidosis CNS involvement is in the brain parenchyma, leptominenges, and cranial nerves, particularly the facial nerve. These occur in 35%, 40%, and up to 50% of patients, respectively (4, 5). Clinical features of neurosarcoidosis are therefore heterogeneous, depending on which area of the CNS is involved and to what extent. For example, a patient with a neurosarcoid intraparenchymal mass lesion may present with headache, mental status changes, and seizures; while a patient with neurosarcoidosis in the hypothalamus may present with disturbances in thirst, sleep, appetite, and temperature. Spinal-cord neurosarcoidosis symptoms include myelopathy or radiculopathy, as seen with our patient. Importantly, neurosarcoidosis is a monophasic illness in two-thirds of patients, but it can also have a relapsing-remitting course or progressive course with episodic deteriorations (6).

Given the variability in clinical symptomatology and time course, the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis requires MRI with contrast to detect abnormalities. Spinal-cord neurosarcoidosis can be intramedullary, extramedullary, or osseous. Intramedullary neurosarcoid spinal-cord lesions, as seen in our patient, account for less than 1% of sarcoidosis cases (5). On MR imaging, they manifest typically with fusiform cord enlargement, mainly in the cervical and thoracic regions (7), low-intensity T1 signal with patchy enhancement, and high-intensity T2 signal. Our patient exhibited some of these features. Extramedullary spinal sarcoidosis typically exhibits low-intensity T1 signal with contrast enhancement and low-intensity T2 signal. Lastly, osseous involvement is typically seen as well-defined, lytic changes on imaging, although skull and vertebral involvement in neurosarcoidosis is very rare (bones of the hands and feet are more commonly involved).

Despite typical imaging characteristics, these signs can mimic other conditions. In the case of the intramedullary spinal lesion seen in our case report, the radiologist must differentiate the neurosarcoid spinal lesion from intramedullary tumors such as ependymoma, astrocytoma, or glioma; demyelinating disease such as multiple sclerosis or ADEM; transverse myelitis; and fungal infection (4, 6); and this may not be possible with imaging alone. The treatment for each of these diagnoses varies; operative treatment effective for malignancy is not effective for steroid- or immunosuppressant-responsive spinal-cord sarcoidosis. Therefore, the diagnosis of spinal sarcoidosis is important for early, effective treatment and can be aided by accurate radiologic assessment, although imaging by itself is not sufficiently specific for diagnosis.

In addition to imaging of the spine and head, chest CT demonstrating bilateral lymphadenopathy may provide additional diagnostic clues, as it did with this patient. Other parameters must be considered to aid in diagnosis, including serum ACE levels, lumbar puncture, and biopsy. Our patient’s serum ACE level was mildly elevated at 59. It is important to consider that increased ACE levels are not specific for sarcoidosis and can be encountered in disease states like meningitis, diabetes, and cirrhosis (5). Lumbar puncture was deferred for our patient, given concerns about tissue edema seen on imaging, but (if done) might have exhibited characteristic findings such as elevated total protein, elevated CSF opening pressure, normal or low glucose, mononuclear pleocytosis, and elevated ACE. However, Sakushima and colleagues (2011) found that spinal-cord sarcoidosis had fewer CSF abnormalities than other forms of neurosarcoidosis (8). Biopsy is ultimately definitive in this diagnosis of exclusion, although attempts at extraneural biopsies such as of the lung, lymph nodes, or skin should be made preferentially, given lower morbidity and easier access. A high index of suspicion for the diagnosis is also required because early intervention is associated with a favorable outcome. Our patient had a good response to an initial high-dose steroid therapy (considered first-line), but then required methotrexate (second-line) and is now on mycophenolate (CellCept) and adalimumab (Humira) as he continues to be weaned off of prednisone. Other patients with progressive spinal neurosarcoidosis may encounter this changing medication course.

Radiologists should keep neurosarcoidosis as a diagnostic possibility, even in patients who do not already present with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, and recognize the imaging manifestations. Eighty-seven percent of neurosarcoidosis cases show resolution on imaging, which can parallel clinical improvement, as seen with our patient (4), while others show progression and recurrence despite treatment, making imaging key in both pre- and post-diagnosis evaluation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Cambridge Health Alliance, the Harvard Medical School Cambridge Integrated Clerkship, Dr. Arthur Chang, Dr. Stephan Auerbach, Dr. Anatoli Shabashov, Dr. Oliver Kendall, Dr. David Hirsh, Dr. Anne Fabiny, and Cathy Holcomb for their support.

Footnotes

Published: December 14, 2012

References

- 1.Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885–1889. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar N, Frohman EM. Spinal neurosarcoidosis mimicking an idiopathic inflammatory demyelinating syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:586–589. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.4.586. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nardone R, Venturi A, Buffone E. Extramedullary spinal neurosarcoidosis: Report of two cases. Eur Neurol. 2005;54:220–224. doi: 10.1159/000090714. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginat DT, Dhillon G, Almast J. Magnetic resonance imaging of neurosarcoidosis. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2011;1:15. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.76693. [PubMed] [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JK, Matheus MG, Castillo M. Imaging manifestations of neurosarcoidosis. AJR. 2004;182:289–295. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820289. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang BL, Kuo HC, Chu C, Huang C. Spinal neurosarcoidosis. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2011;20:142–148. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah R, Roberson GH, Cure JK. Correlation of MR imaging findings and clinical manifestations in neurosarcoidosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:953–961. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1470. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakushimi K, Yabe I, Nakano F. Clinical features of spinal cord sarcoidosis: analysis of 17 neurosarcoidosis patients. J Neurol. 2011;258:2163–2167. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6080-3. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]