Abstract

Rice stripe virus-infected females of the small brown planthopper (SBPH, Laodelphax striatellus) usually lay fewer eggs with a longer hatch period, low hatchability, malformation and retarded or defective development compared with healthy females. To explore the molecular mechanism of those phenomena, we analyzed the differential proteomics profiling of the ova between viruliferous and healthy female insects using an isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) approach. We obtained 147 differentially accumulated proteins: 98 (66.7%) proteins increased, but 49 (33.3%) decreased in the ova of the viruliferous females. RT-qPCR was used to verify the 12 differential expressed proteins from iTRAQ, finding that trends in the transcriptional change for the 12 genes were consistent with those at the proteomic level. Differentially expressed proteins that were associated with meiosis (serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2B and cyclin B3) and mitosis (cyclin B3 and dynein heavy chain) in viruliferous ova may contribute to low hatchability and defective or retarded development. Alterations in the abundance of proteins involved in the respiratory chain and nutrition metabolism may affect embryonic development. Our study begins to explain macroscopical developmental phenomena and explore the mechanisms by which Rice stripe virus impacts the development of SBPH.

The small brown planthopper (SBPH, Laodelphax striatellus), an important field pest, can seriously harm grain crops such as rice, not only by sucking the sap of gramineous plants, but also by transmitting several viruses, including Rice stripe virus (RSV), Rice black-streaked dwarf virus and Maize rough dwarf virus, which can lead to more significant yield losses after virus infection1. For example, rice stripe disease caused by RSV commonly causes about 20–30% losses in japonica rice-grown regions of China2. An epidemic of rice black-streaked dwarf disease affected 11.79 × 104 ha in Jiangsu Province from 1991 to 2002 and then expanded into adjacent provinces such as Shandong and Henan3. Maize rough dwarf disease in Spain led to an average loss of 24% in commercial maize fields infected with the virus, up to 68% in areas with the highest incidence4. Among the three viruses, only RSV can be transmitted from the ovary into the eggs with high efficiency5.

RSV is transmitted by SBPH in a circulative, persistent and propagative manner and maternally from the ovary into 75% to 100% of the eggs, but it has not been detected in sperm6. When SBPH feeds on RSV-infected plants, RSV moves with the plant sap into the alimentary canal of the insect, infects the gut epithelial cells of the promesenteron where RSV replicates abundantly, then spreads into the adjacent epithelial cells and enteric muscle layer. It is then released into the hemolymph and, ultimately, infects the salivary glands and is released into the salivary ducts from where it can be transferred to new plants via the saliva released during feeding5. To infect the egg, RSV invades the nurse cell of the germarium through endocytosis mediated by a vitellogenin receptor and eventually enters the eggs7. These complex transmission and multiplication processes of the virus, recruiting of critical host proteins, likely influence the physiological and developmental processes of the insect8,9.

Many previous studies have shown that the infection by plant viruses impacts herbivorous vector insects in numerous ways. When Barley yellow dwarf viruses, vectored by the English grain aphid (Sitobion avenae), infect the aphid, the insect lives longer, produces more offspring and develops faster than the healthy insect10. However, the fecundity of the green rice leafhopper (Nephotettix cincticeps) is significantly lower after Rice dwarf virus infection11. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus can also shorten the life span of adult Bemisia tabaci and the number of eggs laid12. While Tomato spotted wilt virus infection does not alter the developmental period from egg to adult, the rate of reproduction and survival of its vector insect, Western flower thrip (Frankliniella occidentalis)13. For SBPH, RSV can invade eggs, where it can proliferate and accumulate from the antenatal stage to the 7th day postpartum. Infection by RSV not only decreases the number of eggs laid per female, but also reduces the hatchability of viruliferous eggs. Microscopic observation of the eggs showed that nearly 25% of the viral-infected eggs were developmentally retarded or defective, and nearly 75% of the infected eggs developed slowly but without any abnormal morphology7. Moreover, the survival rate of 1st and 2nd instar nymphs was significantly reduced by 50% in the viruliferous insects compared with those without RSV14. RSV also shortens the 5th instar stage and the total nymphal stage, which is thought to be in response to decreased egg production and to result in an increase in the distance that adults can migrate and thus transmit the virus15.

When several embryonic developmental genes of SBPH were subjected to RT-qPCR to analyze viral influence on eggs at the transcriptional level, the expression of Ls-Dorsal, Ls-CPO and other 11 embryonic developmental genes differed significantly in viruliferous eggs compared with noninfected eggs. A decrease in the transcription factor Dorsal, which initiates dorsal–ventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo, may lead to developmental abnormalities of eggs. Chorion peroxidase (CPO), which plays a role in forming the rigid, insoluble chorion of eggshell, is inhibited by RSV, which may cause a defect in the chorion and thus impair protection of the egg against other pathogens7. In an RT-qPCR analysis, CYP307A1, involved in the ecdysteroid pathway, and JHAMT, involved in the juvenile hormone pathway, were found to be upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in RSV-infected 5th instars of SBPH and thus thought to contribute to the expedited development of the nymphs15. Although those studies have helped us to uncover the physiological and morphological influences of viruses on the vector insects, few studies have focused on proteomic changes in the host resulting from virus infection. Documenting disorders in protein accumulation in viruliferous insects can also be a powerful tool for revealing the mechanisms underlying developmental changes caused by the virus.

Many techniques such as 2D gel based technology and isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) can be used to identify variations in proteins under different conditions16. With a stable isotope labeling strategy, iTRAQ can simultaneously label and accurately quantify proteins, even low abundance proteins, from multiple samples17. So, iTRAQ is frequently used to explore virus-related questions18,19. In this study, we used iTRAQ to identify differentially expressed proteins in SBPH mature ova infected with RSV compared with uninfected mature ova to clarify protein changes that result from infection of RSV and to understand the interactions between RSV and L. striatellus more comprehensively. Study of the ova rather than the zygote can reveal the influence of RSV on SBPH from the beginning of embryonic development and exclude the interference of sperm, which cannot be infected with RSV.

Results

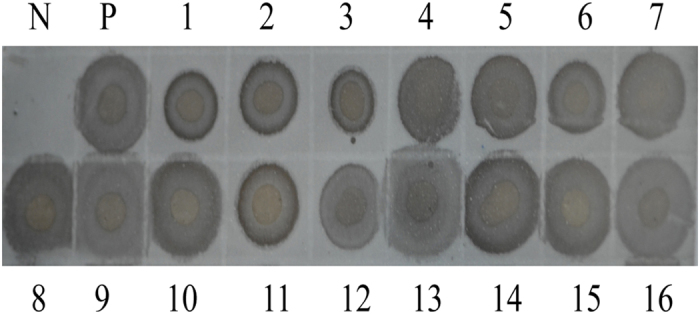

Detecting viruliferous ova from females

To ensure that viruliferous females lay a high rate of viruliferous ova, we used dot blot immunobinding assay to analyze the viruliferous rate (VR) of 16 nymphs (3rd instar) from ova of viruliferous females. All 16 nymphs were viruliferous, indicating that the VR of ova laid by viruliferous females was 100%, which guaranteed the availability of the viruliferous sample for subsequent experiment and analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Detection of viruliferous ova excised from RSV-infected females fed on healthy plants through dot blot immunobinding assay.

N: healthy SBPH; P: viruliferous SBPH; lanes 1–16: 16 nymphs borne by viruliferous female.

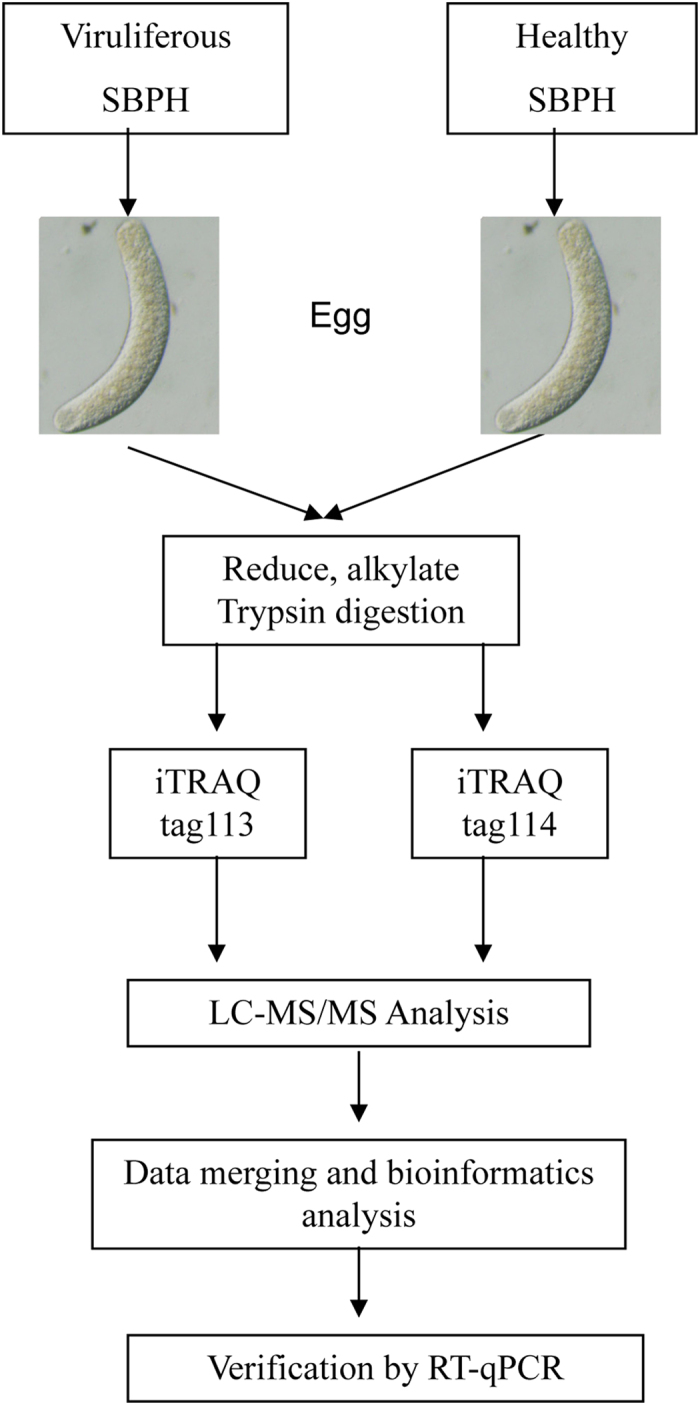

Identification of differentially expressed proteins between viruliferous and healthy ova by iTRAQ

Differentially expressed proteins between RSV-infected and healthy ova were identified and quantified by 2-plex iTRAQ labeling and LC-MS/MS analysis, respectively (Fig. 2). Based on the LC-MS/MS analysis, 334 proteins were identified from the viruliferous and healthy ova. Among those proteins, 147 were differentially accumulated between the two samples (false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.01, fold changes >1.2 or <0.83): 98 (66.7%) increased and 49 (33.3%) decreased under the RSV-infection condition. Detailed information on the differentially expressed proteins, accession numbers and ratios are showed in the Table 1.

Figure 2. Experimental workflow.

The viruliferous and healthy female SBPHs were dissected when they reached the 4th peak hatching period when ova were mature, and viruliferous and healthy ova samples, respectively, were collected and lysed. Differentially expressed proteins were quantified relatively using iTRAQ labeling (tags 113 and 114, respectively) and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. At the end of the study, we conducted a general bioinformatics analysis to provide a complete list of RSV-responsive proteins in the ova and verified some proteins by RT-qPCR.

Table 1. List of differentially expressed proteins in ova of SBPH after RSV infection.

| Accession numbera | Proteins | Unique peptidesb | Sequence coverage [%]c | Ratiod |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation | ||||

| 662195687 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 3-like | 1 | 17.4 | 2.484511 |

| 662197941 | translationally controlled tumor protein homolog | 1 | 6.8 | 2.067828 |

| 641661996 | transcription elongation factor B polypeptide 2 | 1 | 6.9 | 1.984711 |

| 662206187 | eukaryotic peptide chain release factor GTP-binding subunit ERF3A | 1 | 4.5 | 1.830048 |

| 187123194 | ribosomal protein L24 | 1 | 8.3 | 1.785167 |

| 648215847 | 40S ribosomal protein S5 | 2 | 8.8 | 1.604823 |

| 662201329 | 40S ribosomal protein S23 | 2 | 8.4 | 1.528438 |

| 641647602 | 60S ribosomal protein L21-like | 2 | 12.7 | 1.51912 |

| 187115160 | ribosomal protein S17 | 1 | 10.8 | 1.457962 |

| 193580101 | 40S ribosomal protein S9 | 1 | 16.2 | 1.431053 |

| 662197167 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A | 1 | 5 | 1.415218 |

| 662199441 | elongation factor Tu, mitochondrial-like | 1 | 2.7 | 1.406708 |

| 662207737 | 60S ribosomal protein L11 | 1 | 13 | 1.379142 |

| 662209085 | 60S ribosomal protein L8 | 3 | 14.4 | 1.369597 |

| 662209707 | 60S ribosomal protein L12 | 1 | 5.5 | 1.350648 |

| 662184235 | 40S ribosomal protein S11 | 2 | 7.2 | 1.33406 |

| 662218739 | 60S ribosomal protein L4-B-like, partial | 2 | 12.5 | 1.324579 |

| 187129222 | ribosomal protein L34 | 1 | 6.7 | 1.317411 |

| 662186416 | 40S ribosomal protein SA | 1 | 5.6 | 1.295956 |

| 662210930 | 60S ribosomal protein L23 | 1 | 7.1 | 1.270119 |

| 187129228 | 40S ribosomal protein S25 | 2 | 9.5 | 1.266763 |

| 641679542 | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein 27C-like | 2 | 5.6 | 1.252255 |

| 662200191 | 60S ribosomal protein L32-like | 1 | 7.5 | 1.221087 |

| 240849131 | ribosomal protein S6 | 1 | 3.6 | 1.211985 |

| 641673750 | ribosomal protein S28e-like | 2 | 32.3 | 0.815808 |

| 662208447 | eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-I-like | 1 | 4.2 | 0.780624 |

| 641662274 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C | 1 | 1.5 | 0.700217 |

| 662224988 | 40S ribosomal protein S8-like, partial | 1 | 25.9 | 0.658957 |

| Metabolism | ||||

| 662219845 | persulfide dioxygenase ETHE1, mitochondrial | 1 | 3.2 | 6.127282 |

| 328697388 | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1 | 1.4 | 1.652311 |

| 641677413 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine–peptide N-acetylglucosaminy-ltransferase-like | 1 | 1.7 | 1.524594 |

| 641654954 | V-type proton ATPase catalytic subunit A | 1 | 8.5 | 1.512928 |

| 328704972 | delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase | 4 | 7.9 | 1.448002 |

| 328700405 | proline dehydrogenase 1, mitochondrial | 1 | 3.6 | 1.341319 |

| 328697410 | DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase 20-like | 2 | 4.2 | 1.32052 |

| 662214999 | glutamate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial-like | 2 | 5.3 | 1.302101 |

| 662210960 | 1,4-alpha-glucan-branching enzyme-like | 1 | 6.2 | 1.27316 |

| 193700143 | aldehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 2 | 2.9 | 1.271559 |

| 662192943 | pyruvate carboxylase, mitochondrial-like | 4 | 3.9 | 1.218207 |

| 641675019 | UTP–glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase-like | 2 | 4.2 | 1.207656 |

| 193580190 | isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP] cytoplasmic-like | 2 | 4.9 | 1.20412 |

| 641659015 | T-complex protein 1 subunit zeta | 1 | 1.3 | 0.8241 |

| 641679894 | probable pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit alpha, mitochondrial | 1 | 2.5 | 0.814525 |

| 328710078 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | 2 | 3.9 | 0.81438 |

| 662210162 | probable 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase B0272.3 | 1 | 3 | 0.793047 |

| 662201252 | phosphoglycerate kinase | 1 | 4.5 | 0.791029 |

| 662193985 | acetyl-CoA carboxylase-like | 3 | 2.9 | 0.769906 |

| 662207937 | glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [NAD(+)], cytoplasmic-like | 1 | 3.4 | 0.744568 |

| 328713184 | very long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 1 | 1.7 | 0.718995 |

| 193669238 | translation initiation factor eIF-2B subunit delta | 1 | 2.1 | 0.701824 |

| 328700025 | 6-phosphofructokinase | 1 | 1.1 | 0.696162 |

| 641647799 | histidine decarboxylase | 1 | 2 | 0.689838 |

| 662205392 | malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial-like ; | 2 | 16.9 | 0.67347 |

| 662195667 | ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase 1 | 1 | 4.9 | 0.632195 |

| Electron transport | ||||

| 662201650 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 7, mitochondrial-like | 1 | 9.2 | 1.359605 |

| 671729049 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (mitochondrion) | 1 | 3.6 | 1.350648 |

| 662197766 | electron transfer flavoprotein subunit beta-like | 1 | 22.5 | 1.320515 |

| 662187693 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 2, mitochondrial | 1 | 2.7 | 1.220327 |

| Response | ||||

| 662204299 | RACK1 guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-like protein | 1 | 3.8 | 2.009609 |

| 662194343 | guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(o) subunit alpha | 1 | 3.7 | 1.984605 |

| 662191009 | ras-related protein Rab6-like | 2 | 13.9 | 1.652277 |

| 641673378 | aldehyde dehydrogenase-like | 1 | 2 | 1.569280 |

| 662216228 | transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase TER94-like | 1 | 3.6 | 1.492503 |

| 193587299 | heat shock protein 70 B2-like | 1 | 8.2 | 1.414212 |

| 662212992 | putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase me31b | 1 | 2.1 | 1.381543 |

| 328705845 | dentin sialophosphoprotein | 1 | 0.6 | 1.320508 |

| 662219635 | heat shock protein 83-like | 1 | 7.3 | 1.320508 |

| 662196678 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 8 | 4 | 12.4 | 1.267469 |

| 662199945 | protein transport protein Sec61 subunit alpha | 1 | 1.9 | 1.234578 |

| 662212366 | ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 17 | 1 | 0.4 | 1.232153 |

| 662224369 | heat shock 70 kDa protein cognate 4-like, partial | 1 | 15 | 1.208884 |

| 662206271 | heat shock 70 kDa protein | 3 | 5.2 | 1.206334 |

| 662196490 | sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit alpha-like, partial | 3 | 17.4 | 1.224616 |

| 193652521 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase WM6 | 1 | 2.4 | 0.696162 |

| Cell cycle | ||||

| 662198987 | serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2B catalytic subunit 2-like | 1 | 15.2 | 1.984675 |

| 662183545 | titin-like | 1 | 0.2 | 1.585952 |

| 662198211 | cofilin/actin-depolymerizing factor homolog | 2 | 16.5 | 0.821183 |

| 187179329 | twinstar | 1 | 4.7 | 0.79105 |

| 662201759 | G2/mitotic-specific cyclin-B3-like | 1 | 1.9 | 0.61666 |

| 662211502 | AP-2 complex subunit alpha | 1 | 1.4 | 0.493967 |

| 662185744 | dynein heavy chain, cytoplasmic-like | 1 | 0.2 | 0.194088 |

| Transport | ||||

| 662197932 | ras-related protein Rab-2A | 1 | 9.4 | 1.984636 |

| 662183037 | plasma membrane calcium-transporting ATPase 3-like | 1 | 1.7 | 1.685486 |

| 326319966 | V-type proton ATPase subunit D | 1 | 2.6 | 1.486314 |

| 193634236 | innexin inx2 | 1 | 2.5 | 1.486244 |

| 328711155 | clathrin heavy chain | 2 | 1.9 | 1.439576 |

| 662224735 | V-type proton ATPase subunit E-like | 1 | 5.8 | 1.358345 |

| 662218609 | ADP-ribosylation factor 2-like, partial | 1 | 8.4 | 1.27316 |

| 662187312 | fatty acid-binding protein, muscle | 1 | 6.8 | 1.237659 |

| 187121188 | bicaudal | 1 | 6.6 | 0.815664 |

| 662190099 | apolipophorins-like | 1 | 0.3 | 0.802221 |

| 641657530 | glutamate receptor ionotropic, kainate 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.79105 |

| 662206445 | ras-related protein Rab-7a | 1 | 5.2 | 0.696162 |

| 641666000 | ATP-binding cassette sub-family E member 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.60393 |

| 662213752 | vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 29 | 1 | 5.5 | 0.55669 |

| Transcription regulation | ||||

| 662211365 | forkhead box protein O-like, partial | 1 | 3.4 | 2.099884 |

| 641667108 | segmentation protein Runt-like | 1 | 2.1 | 1.364041 |

| 662221075 | histone H4 | 1 | 50.5 | 1.344955 |

| 328717963 | probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX5 | 1 | 4 | 1.26917 |

| Signal transduction | ||||

| 662218361 | spectrin beta chain, erythrocytic-like, partial | 1 | 3.8 | 2.484511 |

| 240848699 | troponin C-like | 1 | 9.3 | 2.166203 |

| 648215987 | FK506-binding protein 1 precursor | 1 | 8.1 | 1.984675 |

| 641649210 | calcium/calmodulin-dependent 3,5-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 1C-like | 1 | 1 | 1.585871 |

| 662185726 | ras-related protein Rab-8B-like | 1 | 8.3 | 1.527754 |

| 662191522 | ralA-binding protein 1-like | 1 | 1.6 | 0.592953 |

| Others | ||||

| 641667476 | dystonin | 1 | 0.2 | 5.332768 |

| 193618005 | T-complex protein 1 subunit gamma-like | 1 | 2 | 2.317678 |

| 641657060 | trichohyalin-like | 1 | 2.9 | 2.127308 |

| 662221462 | zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 13-like, partial | 1 | 1.4 | 2.00459 |

| 641654607 | uncharacterized protein LOC103308150 | 1 | 5.1 | 1.984605 |

| 662206904 | uncharacterized protein LOC103513857, partial | 1 | 2.2 | 1.874966 |

| 641664858 | uncharacterized protein LOC100571486 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.805057 |

| 641679348 | zinc finger MYM-type protein 1-like | 1 | 1.1 | 1.65225 |

| 237874213 | Obg-like ATPase 1 | 1 | 2.5 | 1.616551 |

| 662198825 | uncharacterized protein LOC103509702 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.478131 |

| 641659614 | uncharacterized protein LOC103308837 | 1 | 0.7 | 1.457034 |

| 641658025 | uncharacterized protein LOC100573999 | 1 | 2.1 | 1.422523 |

| 662203311 | uncharacterized protein LOC103512009 | 1 | 2.1 | 1.409739 |

| 662199313 | T-complex protein 1 subunit theta | 2 | 4.7 | 1.355449 |

| 662224929 | troponin T-like | 2 | 5.7 | 1.29113 |

| 298676439 | tubulin beta-1 chain | 7 | 23.5 | 1.286363 |

| 641651626 | tubulin beta chain-like | 1 | 7.7 | 1.280335 |

| 328699232 | spectrin beta chain | 4 | 1.7 | 1.248244 |

| 641678036 | spectrin alpha chain | 2 | 4.2 | 1.238482 |

| 328708622 | muscle LIM protein Mlp84B-like | 2 | 4.8 | 1.231617 |

| 328709476 | multiple inositol polyphosphate phosphatase 1-like | 1 | 1.5 | 1.229761 |

| 328703083 | alpha-actinin, sarcomeric | 3 | 10.9 | 1.222747 |

| 662217109 | uncharacterized protein LOC103519217 | 1 | 1.3 | 1.200012 |

| 662199835 | neural-cadherin-like | 1 | 6.7 | 0.8241 |

| 328715019 | transketolase-like protein 2 | 1 | 2.1 | 0.819711 |

| 662194096 | paxillin | 1 | 4.8 | 0.810566 |

| 662187362 | GTP-binding protein 1-like | 1 | 4.6 | 0.803458 |

| 662199465 | lisH domain and HEAT repeat-containing protein KIAA1468 homolog | 1 | 1.2 | 0.784215 |

| 328702659 | uncharacterized protein LOC100569797 | 1 | 1.8 | 0.777457 |

| 328721582 | netrin-1-like | 1 | 5.4 | 0.776104 |

| 662204082 | myosin heavy chain, muscle-like | 3 | 12.2 | 0.77215 |

| 662198855 | immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat protein 2-like | 1 | 4.3 | 0.768863 |

| 641646988 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 10-like | 1 | 8.9 | 0.738145 |

| 648216270 | uncharacterized protein LOC100168138 | 1 | 5.9 | 0.706124 |

| 641673054 | uncharacterized protein LOC103310269 | 1 | 2.9 | 0.702618 |

| 662218667 | uncharacterized protein LOC103520057 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.648129 |

| 662197467 | putative uncharacterized protein DDB_G0282133 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.635234 |

| 641668388 | microtubule-associated serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.55669 |

| 662219363 | uncharacterized protein MAL13P1.304-like, partial | 1 | 1.1 | 0.542914 |

| 662189113 | ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 1, partial | 1 | 1.4 | 0.449017 |

| 662208914 | uncharacterized protein LOC103514896 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.329166 |

| 662188243 | uncharacterized protein DDB_G0284459-like | 1 | 1.7 | 0.003 |

aProtein accession number from NCBI.

bNumber of unique peptides identified for each protein.

cPercentage sequence coverage of identified proteins.

dRatios of RSV-infected/mock-infected proteins.

Bioinformatics analysis

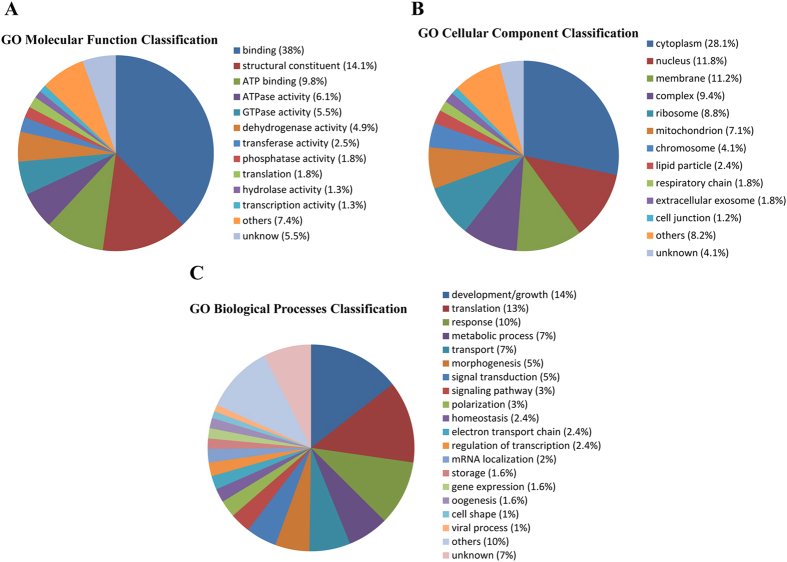

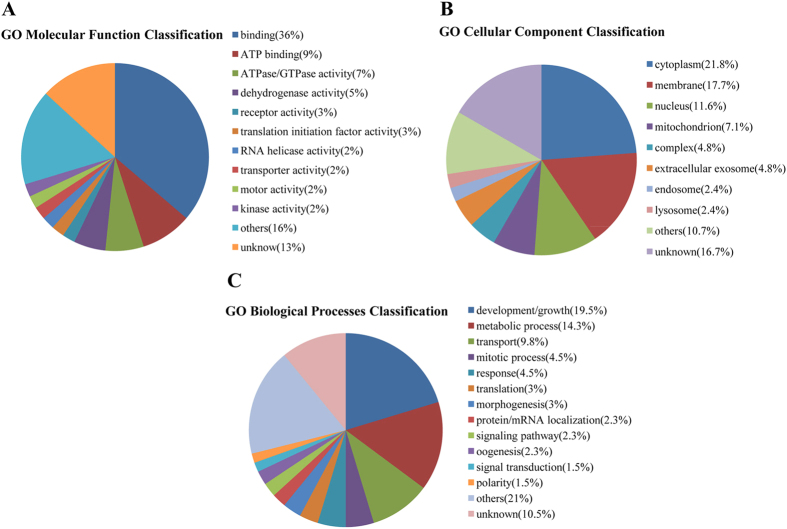

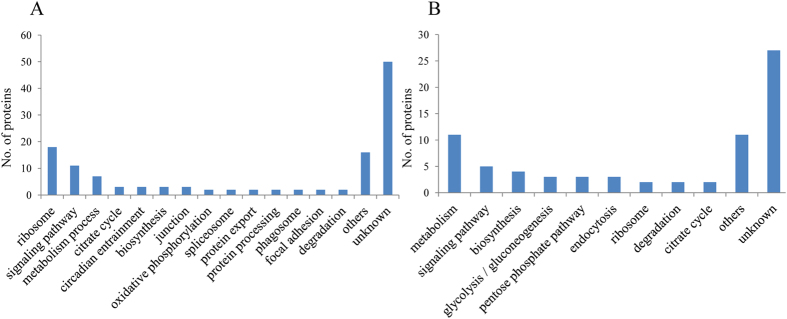

To understand the differentially accumulated proteins, the proteins were disposed by bioinformatic tools. All differentially expressed proteins were submitted to Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org) for gene annotation, including molecular function, biological process and cellular component. For both upregulated and downregulated proteins, the main molecular functions were binding and ATP binding. According to biological process, upregulated proteins were mainly classified as development/growth, translation and response, while downregulated proteins were mainly in development/growth, metabolic process, and mitotic process. The cellular component of upregulated and downregulated proteins was mainly cytoplasm, nucleus and membrane. Detailed information can be found in Figs 3 and 4. We analyzed pathways of the differential proteins through the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/). In the upregulated proteins, the main pathways were related to ribosome, signaling pathway and metabolism process. Similarly, among the downregulated proteins, pathways were the dominant grouping sector for proteins involved with metabolism process, signaling pathway and biosynthesis (Fig. 5).

Figure 3. Gene ontology (GO) assignment of upregulated proteins related to molecular function, biological processes and cellular component.

Figure 4. Gene ontology (GO) assignment of downregulated proteins related to molecular function, biological processes and cellular component.

Figure 5. Pathway analysis of upregulated (A) and downregulated (B) proteins.

The y-axis represents the number.

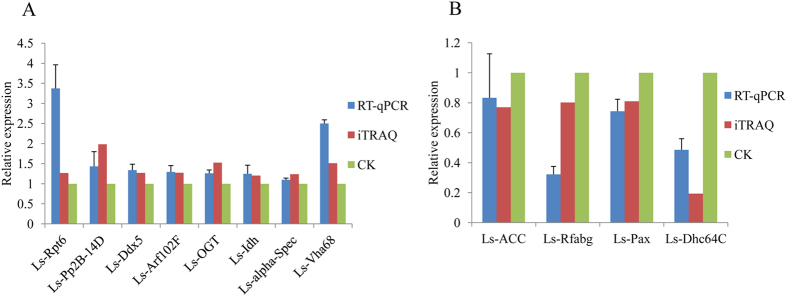

Validation of the proteomics data at the RNA level by RT-qPCR

From a proteomics perspective, we found many proteins that differentially accumulated in ova infected with RSV compared with uninfected ova. To evaluate the proteomic data and correlation between mRNA transcription level and protein abundance, we performed RT-qPCR to quantify the mRNA transcript level for 12 proteins that were selected according to the proportion of their up- and downregulation and availability of the mRNA sequence from the SBPH transcriptome20 (Table 2). The biological processes of those proteins are mainly metabolic process (Ls-ACC, Ls-Vha68, Ls-OGT and Ls-Idh), cell cycle (Ls-Pp2B-14D and Ls-Dhc64C), response (Ls-Rpt6), and transport (Ls-Arf102F and Ls-Dhc64C). The trend in transcriptional variation for all the selected proteins was consistent with the proteomic changes determined in the iTRAQ analysis, suggesting that iTRAQ is a reliable way to identify and quantity the expressed differentially proteins of the SBPH (Fig. 6).

Table 2. List of genes selected for RT-qPCR assay.

| Accession number | Proteins | Genes | Ratio | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 662196678 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 8 | Ls-Rpt6 | 1.267469 | response to DNA damage stimulus; proteasomal protein catabolic process |

| 662198987 | serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2B catalytic subunit 2-like | Ls-Pp2B-14D | 1.984675 | meiotic division |

| 328717963 | probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX5 | Ls-Ddx5 | 1.26917 | regulation of pre-mRNA splicing; transcriptional coactivator |

| 662218609 | ADP-ribosylation factor 2-like, partial | Ls-Arf102F | 1.27316 | protein transport |

| 641677413 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine--peptide N-acetylglucosa- minyltransferase-like | Ls-OGT | 1.524594 | energy/glycogen metabolism |

| 193580190 | isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP] cytoplasmic-like | Ls-Idh | 1.20412 | tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| 641678036 | spectrin alpha chain | Ls-alpha-Spec | 1.238482 | constituent of the cytoskeletal network; maintenance of cell shape |

| 641654954 | V-type proton ATPase catalytic subunit A | Ls-Vha68 | 1.512928 | ATP metabolic process |

| 662193985 | acetyl-CoA carboxylase-like | Ls-ACC | 0.769906 | fatty acid metabolism |

| 662190099 | apolipophorins-like | Ls-Rfabg | 0.802221 | transport |

| 662194096 | paxillin | Ls-Pax | 0.810566 | cytoskeletal protein |

| 662185744 | dynein heavy chain, cytoplasmic-like | Ls-Dhc64C | 0.194088 | mitotic nuclear division; transport |

Figure 6. Validation of iTRAQ results through RT-qPCR of viruliferous and healthy ova samples.

β-actin was used to normalize protein levels; mean expression levels of selected genes are denoted by the histogram bars (±SD) from triplicate repeats. Error bars represent SD. A: Eight genes (Ls-Rpt6, Ls-Pp2B-14D, Ls-Ddx5, Ls-Arf102F, Ls-OGT, Ls-Idh, Ls-alpha-Spec and Ls-Vha68) upregulated at protein and transcription levels. B: Four genes (Ls-ACC, Ls-Rfabg, Ls-Pax and Ls-Dhc64C) downregulated at the two levels. Blue and red represents the expression level of viruliferous ova using RT-qPCR and iTRAQ method respectively; gray (CK) represents that of healthy ova for negative control.

Discussion

For nonparthenogenetic insects, such as Drosophila melanogaster and SBPH, the development of the mature egg is arrested during meiosis prophase I and suspended in its metabolism and cell cycle until the insect ovulates21. The eggs are reactivated by mechanical stimulation and hydration resulting from passage of the egg within the narrow oviducts. First, they complete meiosis, and the male and female pronuclei become integrated to form the zygote, which then undergoes rapid cleavage cycles in which the nucleus divides without cytokinesis. These processes, from the end of prophase I to the rapid cleavage cycle 13, still use the maternal mRNA and proteins; zygotic transcription does not occur until the mid-blastula transition (MBT), when the divided nucleus becomes separated by a membrane and independent cells form22.

Considering these processes in the context of the results of our study, we deduced that meiosis in viruliferous ova is likely to be disturbed by the decreased level of G2/mitotic-specific cyclin B3 and the increased level of serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2B catalytic subunit 2 (Pp2B-14D). Cyclin-B3, a positive regulatory subunit of the cyclin-dependent kinase, is correlated with female fertility. In the crab ovary, increased expression of cyclin B during late vitellogenesis and final maturation of ova is considered to associated with meiotic maturation of the oocyte23. In addition, a mutation in cyclin B3 in Drosophila females leads to abnormal oogenesis, fewer eggs laid and malformed embryos24. In Caenorhabditis elegans, the loss of cyclin B3 in embryos through RNA interference (RNAi) blocks meiosis II and causes meiotic defects25. Pp2B-14D is a subunit of calcineurin that is necessary for meiotic progression beyond metaphase I26. Overexpression of a persistently active form of Pp2B-14D in a Drosophila female germline also causes meiotic defects27. Therefore, the repression of maternal cyclin-B3 and the accumulation of Pp2B-14D induced by RSV may delay the completion of meiosis and lead to defective eggs, thus explaining the low hatchability and defective development.

Our study also showed that the rapid cleavage cycles of the embryonic nucleus may be disturbed by lowered level of cell cycle-related proteins such as cyclin B3 in viruliferous ova. Cyclin B3 controls the transition from metaphase to anaphase and participates in many cell cycle events such as the timely progression of mitotis and the onset of anaphase. Knockdown of cyclin B3 in Caenorhabditis elegans embryo results in a longer prophase and prometaphase, and a prolonged delay in metaphase25. Loss of mitotic cyclins during cleavage cycles 8 and 9 in Drosophila as a result of RNAi causes various mitotic defects and even nuclear arrest28. Dynein heavy chain, cytoplasmic (Dhc64C), which was also downregulated in the viruliferous ova of SBPH, is related to spindle formation, movement of chromosomes in prometaphase and anaphase A and control of the timing of the onset of anaphase29. The absence of cytoplasmic dynein by RNAi leads to metaphase arrest and mitotic defects such as anaphase delay and chromosome misalignment in the Drosophila S2 cell line30. Therefore, reduced levels of cyclin B3 and Dhc64C in the viruliferous ova suggest that RSV infection may impair and arrest mitosis, which may also contribute to delayed or defective development of eggs from viruliferous females.

Previous studies have suggested that the mitochondria genes are still silenced before MBT, which means that the embryo utilizes the mitochondrial transcripts and proteins of the ova to perform respiratory-chain function31. But viral infection disturbs the morphology, location and respiratory chain of the mitochondria32. Similarly, in our study, various proteins were upregulated, e.g., many electron-transport-chain related proteins such as two components of NADH dehydrogenase (NADH dehydrogenase iron-sulfur protein 7 and 2) and cytochrome c oxidase subunit II in viruliferous ova, indicating a disorder in respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation compared with the healthy sample, which may impact the synthesis of ATP and influence subsequent fertilization, cleavage and embryonic development33. Changes in the respiratory chain caused by RSV infection may also induce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) beyond the level of the antioxidant system34. Because of the lack of mitochondrial DNA-protecting proteins and poor restoration mechanism, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) adjacent to the respiration chain becomes the preferred target of ROS35. The impairment of mtDNA may also induce the release of an apoptotic factor and result in cellular apoptosis36.

The yolk of the ovum contains nutrients including protein, lipid and glycogen that are transported from the nurse cells and fat body to support eventual embryonic development37,38. RSV infection induced changes in 26 proteins (17.7%) participating in metabolic processes, including protein, lipid and glycogen metabolism, which may affect nutrient utilization for embryonic development (Table 1). This alteration to nutrition may contribute to the upregulation of forkhead box protein O (FoxO), which functions to handle nutrient changes during development by regulating the insulin signaling pathway and cooperating with the cAMP pathway39. In Drosophila melanogaster, 28% of the nutrition-related genes are regulated by FoxO. Moreover, FoxO may induce a decrease in cell number by mediating insulin signaling and inhibit development through the gene d4E-BP40, which may prolong the hatch period.

Heat shock 70 kDa proteins (Hsp70) regulate translocation, the assembly and folding of proteins and inhibit the caspase-dependent apoptosis41. Our result showed that RSV induced the expression of Hsp70. The high level of Hsp70 is considered to improve the survival rate during hyperthermia, but may lead to the over-stimulation or -inhibition many signaling pathways related to cell multiplication, maturation and apoptosis, which will eventually influence development, growth and survival42,43.

In our study, the change in expression of some proteins may be due to aiding in replication of RSV. Without any system for protein synthesis, RSV needs to take over the ribosomal proteins (RPs) and enzymes of the host for translation of viral proteins and replication44. Guanine nucleotide-binding protein (RACK1), a protein that was higher in viral sample, was demonstrated to be a cellular factor that aids virus infection through an internal ribosome entry site and contributes to virus translation and replication in Drosophila melanogaster45. Through a comparative analysis of the transcriptome of SBPH, the level of two RPs was shown to increase in viruliferous insects20. Among the differentially expressed proteins in our study, 20 RPs were identified, and 18 (90%) accumulated to a high level in the viruliferous samples, suggesting that RPs might play key roles in viral protein synthesis for RSV duplication, indicating that RSV may proliferate and accumulate uninterruptedly in ova. Some of the enriched RPs, such as RpS23, RpL11, RPL21, RpL8, and other non-RP protein (hsp83, cyclin B3 and tubulin) also participate in the duplication of the centrosome or in the centrosome cycle28,46,47. The number of centrosomes has a significant impact on the number of spindle poles and accurate chromosome segregation48. Therefore, superabundant RPs and centrosome-related proteins for SBPH may lead to an alteration in the centrosome number, which will lead to mono- or multi-polar spindles and failure of chromosome segregation and errors in cell division49,50.

In our study, some proteins were upregulated probably to assist virus transmission in the ovum or early embryo. Transport protein Sec61 and transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase TER94, both upregulated in our study, participate in virus entry and infection in insects and mammals51. Three subunits of vacuolar ATPase (subunit E and D and catalytic subunit A) also accumulated in the viral sample; vacuolar ATPase is involved in viral entry, in releasing nucleic acid, replication and proper folding of viral proteins52. Meanwhile some enriched antiviral proteins were found in the differentially expressed proteins, which may inhibit the influence of RSV before or after spawning. Putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase me31b was identified as performing an antiviral function in both insect cells and adult flies53. Ras-related protein Rab6 regulates phagocytosis to inhibit virus infection through actin reorganization in Drosophila melanogaster and shrimp54.

In conclusion, we obtained 147 differentially expressed proteins, 98 were upregulated and 49 downregulated, in the ova between viruliferous and healthy female insects of L. striatellus through the iTRAQ method. Determining the variations in proteins should help us to understand the effect of RSV on SBPH ova at the proteomic level and explain phenomena such as low hatchability, developmental retardation and defects. But some protein changes induced by RSV cannot be explained well and need further experimental study. Our analysis of changes in proteins in the RSV-infected SBPH ova provides insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying RSV-induced phenomena.

Methods

Insect rearing and determining the infection rate of ova

Viruliferous and healthy SBPH were raised in separate glass beakers that each contained about 15 rice plants. The glass beakers were placed in an incubator at 28 °C with 16 h light/8 h dark. Rice plants are replaced with new ones every week to supply adequately nutrients. To verify whether the ova laid by viruliferous females were infected, an individual viruliferous female insect was allowed to feed in a glass beaker, and 16 offspring (3rd instar nymphs) were collected and checked for RSV through a dot blot immunobinding assay using a monoclonal antibody against RSV and the method of Wang55.

Protein extraction and proteinase digestion

After the female SBPH reached the 4th peak hatching period56, we excised the ova from the ovary of the females. The samples were dissolved in moderate lysis buffer (7 M carbamide, 2 M thiocarbamide, 0.1% CHAPS) and suspended for several seconds, then broken by ultrasonication (1.2 s on, 2 s off) and then incubated at room temperature for 30 min before being centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then transferred into a new tube. The Bradford method was used to measure the protein concentration57. After overnight digestion in 50 μL trypsin solution at 37 °C, viruliferous and healthy samples were labeled with iTRAQ reagents 113 and 114 (AB Sciex, Foster City, USA), respectively.

2DLC-MS/MS analysis

The labeled peptide fragments from each sample were reconstituted with mobile phase A (98% ddH2O, 2% acetonitrile, pH 10) and pre-separated with mobile phase B (98% acetonitrile, 2% ddH2O, pH 10) using RIGOL L-3000 High performance Liquid Chromatography system with an RP analytical column (Durashell-C18, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm, 100 Å) at 0.7 mL min−1.Then the peptides were redissolved in 2% methyl alcohol and 0.1% formic acid and subsequently separated using a ABI-5600 system (Applied Biosystems) with an EASY-Spray column (12 cm × 75 μm, C18, 3 μm) at 350 nL min−1. Mobile phase A and mobile phase B were 100% H2O with 0.1% formic acid and 100% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, respectively.

Protein identification and quantification

Raw data were collected by Analyst QS 2.0 controlling software (AB Sciex), and Maxquant (version 1.5.2.8, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany) was used to identify the proteins in a search of the protein database of Hemiptera downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Parameters for protein identification were as follows: MS/MS tol. (FTMS) = 20 ppm, MS/MS tol (ITMS) = 0.5 Da, oxidation (M), FDR ≤ 0.01. The significantly different ratio was set at 1.2-fold: proteins were considered as upregulated if the ratio was >1.2 and downregulated if the ratio was <0.83.

Bioinformatics analysis

Protein annotation of the identified differentially expressed proteins, including molecular function, cellular component and biological process, was performed using Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org/)58 to search for comprehensive, high-quality protein functional information and mainly based on Flybase, Interpro and UniProt Knowledgebase. The pathways were analyzed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/)59.

Verification by real-time PCR

We used Bioedit software (version: 7.2.5.0) to create a local transcriptome of SBPH based on sequencing data assembled from SRX016333 and SRX016334 of NCBI by RunAssembly in the program Newbler (version 2.6)60. The 12 selected protein sequences, based on iTRAQ data, were downloaded through the accession number from the NCBI and subjected to a tBlastn similarity search against the local transcriptome. Retrieved gene sequences with an expectation value (E) less than 10−10 were considered to be credible and were used to design the RT-qPCR primers using the program Primer Premier Version 5.0. Viruliferous and healthy samples were triturated in TRIzol (Invitrogen) to extract total RNA. With the FastQuant RT Kit (TIANGEN), 1000 ng RNA was reverse-transcribed to synthesize cDNA. RT-qPCR was performed using the SYBR Green SuperReal PreMix (TIANGEN) with the ABI 7500 Real Time PCR thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) and the following cycle program: 15 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 32 s at 60 °C and 72 °C for 32 s. β-actin was selected as a reference gene to normalize the expression level of target genes. Relative gene expression was computed using the 2−ΔΔCT method61. The experiments were repeated 3 times independently. Healthy samples were used as a negative control. The primers used for the RT-qPCR to verify the iTRAQ result are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, B. et al. Differential proteomics profiling of the ova between healthy and Rice stripe virus-infected female insects of Laodelphax striatellus. Sci. Rep. 6, 27216; doi: 10.1038/srep27216 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2012CB114004), the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303021), and Natural Science Foundation of China (31272017).

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.W. designed the research. B.L and W.L. performed the experiments. B.L. and F.Q. analyzed the data. B.L. and X.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Wu A., Sun X., Pang Y. & Tang K. Homozygous transgenic rice lines expressing GNA with enhanced resistance to the rice sap‐sucking pest Laodelphax striatellus. Plant Breeding 121, 93–95 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. D. et al. Recent Rice stripe virus epidemics in Zhejiang province, China, and experiments on sowing date, disease-yield loss relationships, and seedling susceptibility. Plant Dis. 92, 1190–1196 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Wang X. F. & Zhou G. A one-step real time RT-PCR assay for quantifying rice stripe virus in rice and in the small brown planthopper (Laodelphax striatellus Fallen). J. Virol. Methods 151, 181–187 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achon M. A., Subira J. & Sin E. Seasonal occurrence of Laodelphax striatellus in Spain: Effect on the incidence of Maize rough dwarf virus. Crop Prot. 47, 1–5 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hogenhout S. A., Ammar E. D., Whitfield A. E. & Redinbaugh M. G. Insect vector interactions with persistently transmitted viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46, 327–359 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo Y. et al. Transovarial transmission of a plant virus is mediated by vitellogenin of its insect vector. PLoS pathog. 10, e1003949 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. et al. Rice stripe virus affects the viability of its vector offspring by changing developmental gene expression in embryos. Sci. Rep. 5, 7883, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. W. et al. Proteomic analysis of interaction between a plant virus and its vector insect reveals new functions of hemipteran cuticular protein. Mo. Cell. Proteomics 14, 2229–2242 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar T., Liu W. W. & Wang X. F. Proteomic analysis of interaction between P7-1 of Southern rice black-streaked dwarf virus and the insect vector reveals diverse insect proteins involved in successful transmission. J. Proteomics 102, 83–97 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. W. & Coon B. The effect of barley yellow dwarf virus on the biology of its vector the English grain aphid, Macrosiphum granarium. J. Eco. Entomol. 57, 970–974 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- Nakasuji F. & Kiritani K. Ill-effects of rice dwarf virus upon its vector, Nephotettix cincticeps Uhler (Hemiptera: Deltocephalidae), and its significance for changes in relative abundance of infected individuals among vector populations. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 5, 1–12 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein G. & Czosnek H. Long-term association of tomato yellow leaf curl virus with its whitefly vector Bemisia tabaci: effect on the insect transmission capacity, longevity and fecundity. J. Gen. Virol. 78 (Pt 10), 2683–2689 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijkamp I., Goldbach R. & Peters D. Propagation of tomato spotted wilt virus in Frankliniella occidentalis does neither result in pathological effects nor in transovarial passage of the virus. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 81, 285–292 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Nasu S. Studies on some leafhoppers and planthoppers which transmit virus diseases of rice plant in Japan. Bull. Kyushu. Agric. Exp. Stn. 8, 153–349 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- Wan G. et al. Rice stripe virus counters reduced fecundity in its insect vector by modifying insect physiology, primary endosymbionts and feeding behavior. Sci. Rep. 5, 12527 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D. J. & Hou R. F. Determination and distribution of a female-specific protein in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stal (Homoptera: Delphacidae). Tissue and Cell 37, 37–45 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp N. A. et al. Addressing accuracy and precision issues in iTRAQ quantitation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1885–1897 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wu K. K., Liu Y., Wu Y. & Wang X. F. Integrative proteomics to understand the transmission mechanism of Barley yellow dwarf virus-GPV by its insect vector Rhopalosiphum padi. Sci. Rep. 5, 10971 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Ren Y., Lu C. & Wang X. F. iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics analysis of rice leaves infected by Rice stripe virus reveals several proteins involved in symptom formation. Virol. J. 12, 1 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F. et al. Massively parallel pyrosequencing-based transcriptome analyses of small brown planthopper (Laodelphax striatellus), a vector insect transmitting rice stripe virus (RSV). BMC genomics 11, 303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastock R. & St Johnston D. Drosophila oogenesis. Curr. Biol. 18, R1082–1087 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros W. & Lipshitz H. D. The maternal-to-zygotic transition: a play in two acts. Development 136, 3033–3042 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J. J. & Qiu G. F. Molecular cloning of cyclin B transcript with an unusually long 3′untranslation region and its expression analysis during oogenesis in the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 36, 1521–1529 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H. W., Knoblich J. A. & Lehner C. F. Drosophila Cyclin B3 is required for female fertility and is dispensable for mitosis like Cyclin B. Genes Dev. 12, 3741–3751 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyter G. M., Furuta T., Kurasawa Y. & Schumacher J. M. Caenorhabditis elegans cyclin B3 is required for multiple mitotic processes including alleviation of a spindle checkpoint-dependent block in anaphase chromosome segregation. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001218 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S., Hawley R. S. & Aigaki T. Calcineurin and its regulation by Sra/RCAN is required for completion of meiosis in Drosophila. Dev. Bio. 344, 957–967, (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S., Tsuda M., Akahori S., Matsuo T. & Aigaki T. The calcineurin regulator sra plays an essential role in female meiosis in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 16, 1435–1440 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleland M. L. & O’Farrell P. H. RNAi of mitotic cyclins in Drosophila uncouples the nuclear and centrosome cycle. Curr. Biol. 18, 245–254 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom K. Nuclear migration: cortical anchors for cytoplasmic dynein. Curr. Biol. 11, R326–329 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima G. & Vale R. D. The roles of microtubule-based motor proteins in mitosis comprehensive RNAi analysis in the Drosophila S2 cell line. J. Cell Biol. 162, 1003–1016 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama Y., Filion F., Yoo J. G. & Smith L. C. Characterization of mitochondrial replication and transcription control during rat early development in vivo and in vitro. Reproduction 133, 423–432 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu J. H. et al. Comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes in normal and white spot syndrome virus infected Penaeus monodon. BMC genomics 8, 120 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Blerkom J., Davis P. W. & Lee J. Fertilization and early embryolgoy: ATP content of human oocytes and developmental potential and outcome after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Hum. Reprod. 10, 415–424 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh S., Deecaraman M., Kumar R., Shamsi M. & Dada R. Role of reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations in male infertility. Indian J. Med. Res. 129, 127–137 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji Y., Uedono Y., Ishikura H., Takeyama N. & Tanaka T. DNA damage induced by tumour necrosis factor-alpha in L929 cells is mediated by mitochondrial oxygen radical formation. Immunology 84, 543 (1995). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 15, 2922–2933 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings M. & King R. The cytology of the vitellogenic stages of oogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. I. General staging characteristics. J. Morphol. 128, 427–441 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- King R. C., Bentley R. M. & Aggarwal S. K. Some of the properties of the components of Drosophila ooplasm. Am. Nat. 100, 365–367 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- Mattila J., Bremer A., Ahonen L., Kostiainen R. & Puig O. Drosophila FoxO regulates organism size and stress resistance through an adenylate cyclase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 5357–5365 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger M. A. et al. The Drosophila forkhead transcription factor FOXO mediates the reduction in cell number associated with reduced insulin signaling. J. Biol. 2, 20 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M. P. & Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 670–684, (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. D., Helin A. B., Posluszny J., Roberts S. P. & Feder M. E. Effect of heat shock, pretreatment and hsp70 copy number on wing development in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Ecol. 12, 1165–1177 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs R. A. & Feder M. E. Deleterious consequences of Hsp70 overexpression in Drosophila melanogaster larvae. Cell stress chaperone 2, 60–71 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushell M. & Sarnow P. Hijacking the translation apparatus by RNA viruses. J. Cell Biol. 158, 395–399 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majzoub K. et al. RACK1 controls IRES-mediated translation of viruses. Cell 159, 1086–1095 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller H. et al. Proteomic and functional analysis of the mitotic Drosophila centrosome. EMBO J. 29, 3344–3357 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange B. M., Bachi A., Wilm M. & Gonzalez C. Hsp90 is a core centrosomal component and is required at different stages of the centrosome cycle in Drosophila and vertebrates. EMBO J. 19, 1252–1262 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton D. A. Spindle assembly in animal cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 95–114 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duensing A., Chin A., Wang L., Kuan S. F. & Duensing S. Analysis of centrosome overduplication in correlation to cell division errors in high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated anal neoplasms. Virology 372, 157–164 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg E. A. Centrosome duplication: of rules and licenses. Trends in cell biology 17, 215–221 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda D. et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies SEC61A and VCP as conserved regulators of Sindbis virus entry. Cell Rep. 5, 1737–1748 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S. R., Hernandez R. & Brown D. T. Role of the vacuolar-ATPase in Sindbis virus infection. J. Virol. 85, 1257–1266 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins K. C. et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen reveals that mRNA decapping restricts bunyaviral replication by limiting the pools of Dcp2-accessible targets for cap-snatching. Genes Dev. 27, 1511–1525 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye T., Tang W. & Zhang X. Involvement of Rab6 in the regulation of phagocytosis against virus infection in invertebrates. J. Proteome Res. 11, 4834–4846 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. Z., Zhou Y. J., Chen Z. X. & Zhou X. P. Production of monoclonal antibodies to rice stripe virus and application in virus detection. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 34, 302–306 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Bai X., Dong S. Z., Bian Y. L., Yu X. P. & Chen J. M. The relationgships between yeast-like symbitotes and ovarian development and reproduction of the small brown planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus. Acta Phytophylacica Sinica 36, 421–425 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A. et al. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D204–212 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. et al. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D199–D205 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M. et al. Genome sequencing inmicrofabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437, 376–380 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.