Abstract

Clinical symptoms and signs of ovarian torsion are often nonspecific, and imaging studies have a crucial role in making an accurate timely diagnosis. Ultrasound with color Doppler is often the initial investigation. However, as illustrated in our case, a normal Doppler study cannot exclude the diagnosis of ovarian torsion, and MRI should be performed if a high degree of concern for ovarian torsion persists. We report a case of a case of an 18-year-old female who was diagnosed with ovarian torsion on MRI. To the best of our knowledge, "whirlpool sign on MRI" has not been reported previously. If this sign is present, a specific diagnosis of ovarian torsion can be made.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography

Case report

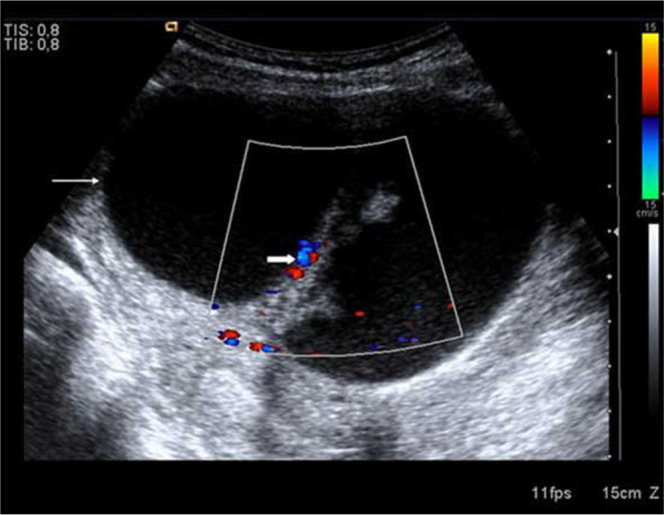

An 18-year-old female presented with acute-onset right lower abdominal pain of 48 hours' duration. Clinical examination showed tenderness in the right lower abdomen without any definite signs of peritonitis. The patient had leukocytosis, with a WBC count of 20,000 cell/cu. mm. Ultrasound with color Doppler showed a large, predominantly cystic, right adnexal lesion with thin septations, mural-septal nodules, and intralesional mural-septal vascularity (Fig. 1). No definite signs of ovarian torsion were identified on ultrasound examination. Right adnexal vascularity was preserved on color Doppler.

Figure 1.

18-year-old female with ovarian torsion. Color Doppler-Ultrasound image shows a large cystic lesion (thin arrow) in the right adnexa with thick internal septations and mural nodules. Vascular flow was noted within the thick septa (thick arrow).

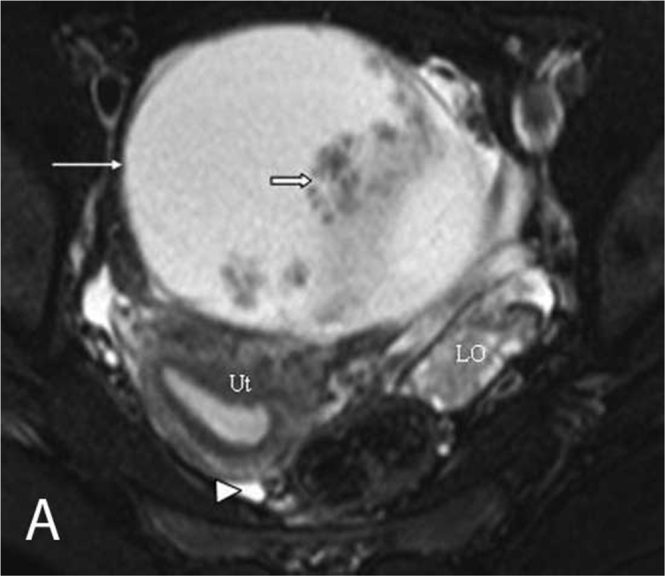

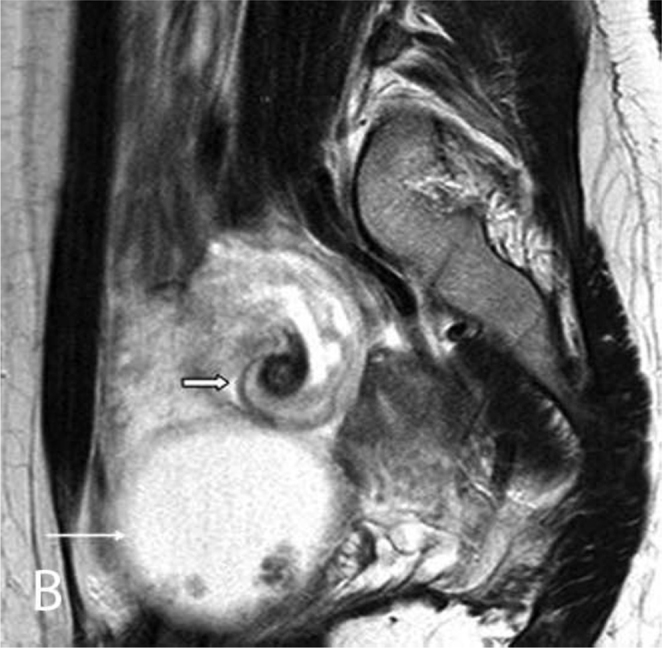

Contrast-enhanced CT showed a thickened right ovary interposed between the cystic lesion and uterus, which raised suspicion of ovarian torsion (Fig. 2). The right ovarian origin and the serous nature of this lesion were established on MRI, which also showed intralesional papillary projections (Fig. 3A). MRI clinched the diagnosis of torsion with precise demonstration of a "whirlpool" appearance of the right adnexa (Fig. 3B). More than two twists of vascular pedicle were precisely demonstrated on MRI, which corroborated the intra-operative findings. Intra-operative frozen sections and subsequent histopathology findings suggested the diagnosis of borderline papillary ovarian cystadenocarcinoma. No evidence of intralesional hemorrhage or adnexal necrosis was seen during the surgery. The patient underwent right-sided salphingo-oophorectomy with pelvic lymph-node dissection and infracolic omentectomy. The postoperative clinical course and imaging findings at six months were within normal limits.

Figure 2.

18-year-old female with ovarian torsion. Contrast-enhanced CT axial image shows thickened right adnexa (thick arrow) interposed between the cystic lesion (thin arrow) and uterus (Ut) which raised suspicion of adnexal torsion. Mild rightward deviation of uterus is also noted.

Figure 3A.

18-year-old female with ovarian torsion. Fat-suppressed, T2-weighted axial MR image showing hyperintense signal within the lesion (thin arrow) with papillary projections (thick arrow). Uterus (Ut) and left ovary (LO) are also noted with mild free fluid in the pouch of Douglas (arrowhead).

Figure 3B.

18-year-old female with ovarian torsion. T2-weighted, sagittal MR image showing "whirlpool appearance" of the right adnexa (thick arrow) suggestive of ovarian torsion. Right ovarian cystic mass is also seen (thin arrow).

Discussion

Ovarian torsion is defined as twisting of the ovary on its ligamentous supports, with consequent compromise of the blood supply. Ovarian torsion is a common gynecologic cause of acute abdomen, with a prevalence of 2.7%, and is commonly seen in the second or third decade of life (1). Though ovarian enlargement of any etiology predisposes women for torsion, ovarian masses, pregnancy, ovulation induction, and previous pelvic surgery are the common underlying causes. Even normal ovaries may undergo torsion, especially in prepubescent females (2).

Early diagnosis of ovarian torsion is crucial, as an unrelieved torsion may progress to peritonitis and infertility due to hemorrhagic infarction of adnexal structures (3). "Twisted vascular pedicle" and "positive whirlpool sign" are specific signs of ovarian torsion on ultrasound (4, 5). Though absence of arterial flow is classically described as the color Doppler sonographic finding in ovarian torsion, this is reported in only 73% of cases (6). CT and MRI are alternate imaging options in these patients. MRI is often preferred in such patients due to better soft-tissue resolution and lower radiation-related risks than those associated with CT. Common CT and MRI features of ovarian torsion include fallopian-tube thickening, smooth-wall thickening of twisted adnexal lesion, ascites, and ipsilateral uterine deviation. Apart from these signs, our patient also showed "whirlpool sign on MRI," which has not previously been reported on MRI to the best of our knowledge. Hemorrhagic tube, hemorrhage within the twisted ovarian mass, and hemoperitoneum are noted when torsion progresses to hemorrhagic infarction, as hemorrhage can easily be diagnosed with fat-suppressed, T1-weighted MR images. Pelvic-fat infiltration and the "lack of enhancement" sign are found to be associated with necrosis of the involved adnexa (7). Pre-operative diagnosis of ovarian torsion is important from the surgical point of view, as in the absence of a grossly necrotic ovary, intra-operative untwisting of the adnexa can be performed for ovarian salvage without significant risk of thromboembolism. Hemorrhagic infarction or gangrene, however, requires surgical removal without any attempt to untwist the ovarian torsion. Due to perilesional adhesions and invasion, malignant ovarian tumors are associated with a lesser risk of torsion of approximately 2% (8, 9).

In our case, there was right ovarian torsion despite its malignant etiology (borderline papillary ovarian cystadenocarcinoma), which is probably explained by the absence of perilesional adhesions or invasion. Ultrasound-Doppler findings did not suggest the diagnosis of ovarian torsion, which was initially suspected on CT and confirmed on MRI. The "whirlpool sign on MRI" was also seen, which is a specific imaging sign for the diagnosis of ovarian torsion.

Footnotes

Published: August 4, 2012

References

- 1.Houry D, Abbot JT. Ovarian torsion: a fifteen year review. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:156–159. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.114303. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman B. Transvaginal sonography of adnexal mass. Radiol Clin North Am. 1992;30:677–691. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bider D, Mashiach S, Dulitzky M, Kokia E, Lipitz S, Ben-Rafael Z. Clinical, surgical and pathologic findings of adnexal torsion in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;173:363–366. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee EJ, Kwon HC, Joo HJ, Suh JH, Fleischer AC. Diagnosis of ovarian torsion with color Doppler sonography: depiction of twisted vascular pedicle. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:83–89. doi: 10.7863/jum.1998.17.2.83. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijayaraghavan SB. Sonographic whirlpool sign in ovarian torsion. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:1643–1649. doi: 10.7863/jum.2004.23.12.1643. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.See-Ying Chiou, Lev-Toaff Anna S., Masuda Emi, Feld Rick I., Bergin Diane. Adnexal Torsion: New clinical and iImaging observations by sonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1289–1301. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.10.1289. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rha SE, Byun JY, Jung SE. CT and MR imaging features of adnexal torsion. Radiographics. 2002;22:283–294. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.2.g02mr02283. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webb EM, Green GE, Scoutt LM. Adnexal mass with pelvic pain. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:329–348. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2003.12.006. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandhu S, Arafat O, Patel H, Lall C. Krukenberg tumor: A rare cause of ovarian torsion. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2012;2:6. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.93038. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]