Abstract

Proton-detection in solid-state NMR, enabled by high magnetic fields (>18 T) and fast magic angle spinning (>50 kHz), allows for the acquisition of traditional 1H-15N experiments on systems that are too big to be observed in solution. Among those, proteins entrapped in a bioinspired silica matrix are an attractive target that is receiving a large share of attention. We demonstrate that 1H-detected SSNMR provides a novel approach to the rapid assessment of structural integrity in proteins entrapped in bioinspired silica.

It is the future strategy in biotechnology to use the processes of nature and not only those of chemistry to create biomaterials. The advantage of natural processes is that they occur under physiological conditions, i.e.: in aqueous environment, around neutral pH and at room temperature and ambient pressure. In this light, such processes are promising candidates for a green-based industry. One interesting class of biomaterials is bio-inspired silica, where the polycondensation of silicic acid is directed by the presence of a polycationic templating molecule or by enzymes1,2,3,4,5,6. In vitro, large amounts of proteins can be properly encapsulated in silica by simply mixing cationic catalyst with the silicic acid and the protein itself7 or, to increase the immobilization yield, the protein can be fused to a biosilica-promoting peptide8,9,10,11,12,13,14. The materials obtained by such natural processes can be easily tuned into different morphologies by the use of slight perturbations of the experimental conditions10,15, and can be easily endowed with peculiar chemical properties, such as fluorescence or catalytic activity by the incorporation of proteins9. In turn, proteins that are entrapped in a silicic matrix become more stable and easily reusable16,17. Despite such a vast applicability, the atomic-level structural characterization of such systems is still far from being routine; indeed, the first solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (SSNMR) spectra of a biosilica entrapped enzyme were published by us only recently18. However, such approach relies on 13C detection and thus is intrinsically sensitivity-limited, requiring several milligrams of material for a thorough characterization19. We have demonstrated that sensitivity can be dramatically improved by means of Dynamic Nuclear Polarization; and in spite of the sizable reduction in spectral resolution intrinsic of DNP at low temperature, it was possible to observe signals of the properly-folded protein20. Of note, in a recent paper, DNP was used to detect the signals from the biosilica-forming peptide PL12, also detecting correlation of silica with lysine sidechains21. Another recent paper used DNP to study the proteic component of the biosilica of intact diatoms22.

Yet, another option is available for increasing the sensitivity in the detection of enzymes entrapped in bioinspired-silica, and this strategy also has the intrinsic advantage of a more informative chemical shift distribution: the acquisition of 1H-detected experiments on 15N-labelled samples. Indeed, the development of fast MAS (>50 kHz) and the development of high-field magnets (>18T) allows for proton-detected techniques, because the frequency of the dipolar interaction stays constant but its effect is mitigated by high field and fast MAS is able to accomplish their averaging. This brings into SSNMR23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 many of the procedures for assignment and collection of structural restraints routinely applied in solution NMR since several years37. Higher fields and faster spinning made it even possible to record 1H-1H correlation experiments38. Recently, 1H-detection based experiments were applied to the study of bone39. It is important to remark that even though 1H-detection has been introduced in solid state NMR already since several years23,24, it is relevant to understand which samples are amenable for its application. Herein, we demonstrate that proton-detected solid-state NMR, enabled by fast magic angle spinning (60 kHz) and high magnetic field (20 T), is feasible for bioinspired-silica-entrapped proteins. In particular, we show that basic 1H-15N correlation spectra29,40 can be acquired in fully protonated, 15N-labelled, samples of two proteins, namely green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the catalytic domain of matrix metalloproteinase 12 (catMMP12), both in fusion with the biosilica-promoting R5 peptide (SSKKSGSYSGSKGSKRRIL) at the C-terminus41.

Results and Discussion

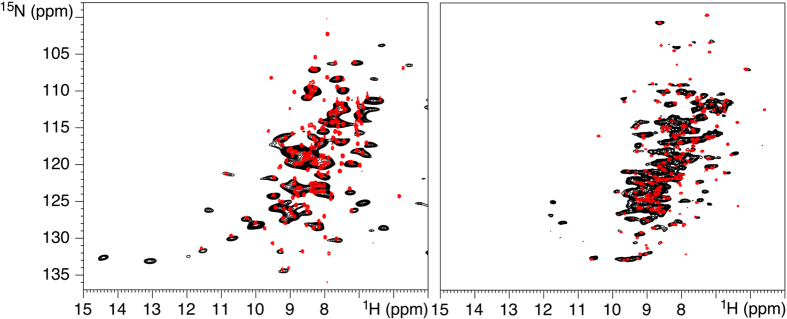

The solid state NMR 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of fully protonated GFP-R5 and catMMP12-R5 (Fig. 1) could be acquired in 4 h 34′ and 10 h 36′ respectively on 3 mg of sample, including the bioinspired-silica matrix. The comparison with solution state 2D 1H-15N HSQC is immediate and reveals that the vast majority of resonances is preserved, confirming the preservation of the structural integrity of the protein (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of catMMP12-R5 (left) and GFP-R5 (right) showing the comparison between the solid-state spectrum (black) and the solution-state spectrum (red).

1H-linewidths are about 240 Hz for catMMP12-R5 and 140 Hz for GFP-R5.

An interesting observation is that a number of resonances could not be observed for MMP12 in the solid state NMR spectrum (Fig. 2 and Table 1). These resonances cluster at, or near to, loops and charged residues. This can be due to two extreme possibilities, i.e.: static disorder or mobility. The first causes heterogeneous broadening of the resonances, the second makes the dipolar-based polarization transfer inefficient. The negligible INEPT-based signal observed previously18, suggests that the prevailing effect is static disorder induced by charge interactions with the silica matrix, or by conformational freezing of loops induced by the the presence of the amorphous matrix. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that the residues with missing resonances in the 1H-detected experiments are always found (with the only exception of L147) in the 13C-based experiment. F237 is not observed in the 13C-based strategy, but is observed in the 1H-based strategy, whereas its neighboring M236 is not. Finally, residues D171 and T205, which flank missing stretches in the 1H-based strategy are even not observed in solution-NMR 13C-detected experiments. Taken together, these observations suggest that there is no correlation in the disappearence of peaks between the 1H-detection strategy and the 13C-detection strategy, and they support the hypothesis that static disorder is sensed to a lesser extent by 13C with respect to 1H nuclei. Some resonances, which are in substantial overlap with others, are not clearly identifiable as missing, but their absence can in be inferred on a structural basis. Some additional peaks appear in the solid state NMR spectrum of catMMP12-R5, which are not present in the solution NMR spectrum, at proton/nitrogen chemical shifts of 11.4/126.2, 13.1/ 133.1, 14.4/132.6 ppm respectively. These are 15N-aliased signals (unaliased 15N chemical shift values are 166.0, 172.8 and172.5, respectively), which belong to the Hδ1 (or Hε2) of the histidine residues coordinating the two zinc ions. These protons are very weak in intensity in the solution NMR because of exchange with water. Two further signals at proton/nitrogen chemical shifts of 6.3/128.6 and 6.9/125.2 ppm, respectively, that are present in the solid state NMR spectrum, can be related instead to the protons of lysines or arginines side-chains, that are lost in the solution NMR spectrum for the same reason.

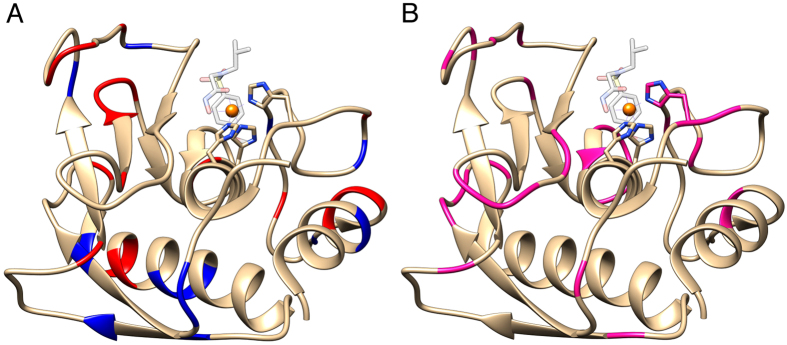

Figure 2.

(A) The X-ray structure of catMMP12 (1RMZ42, which does not carry the R5 fusion) showing the charged residues in blue (positive) and red (negative). (B) The structure of catMMP12 with the residues showing no signals shown in magenta. Apparently, they tend to cluster close to loops or in proximity of charged residues, which can interact with the biosilica matrix.

Table 1. Residues with missing NH resonances in the catMMP12-R5 1H-15N solid state NMR experiment.

| Residue No. | Residue Type | Flanking sequences | Secondary structure Element |

|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | R | RKH | Loop |

| 119 | N | RINNY | Loop |

| 121 | Y | NNYTP | Loop |

| 122 | T | NYTPD | Loop |

| 124 | D | TPDMN | Loop |

| 147 | L | TPLKF | Loop |

| 157 | A | GMADI | Loop |

| 166 | G | ARGAH | Loop |

| 168 | H | GAHGD | Loop |

| 172 | H | DFHAF | Loop |

| 176 | G | FDGKG | Loop |

| 185 | F | HAFGP | Loop |

| 186 | G | AFGPG | Loop |

| 188 | G | GPGSG | Loop |

| 189 | S | PGSGI | Loop |

| 190 | G | GSGIG | Loop |

| 201 | F | EDEFW | Loop |

| 206 | H | TTHSG | Loop |

| 207 | S | THSGG | Loop |

| 208 | G | HSGGT | Loop |

| 209 | G | SGGTN | Loop |

| 211 | N | GTNLF | Loop |

| 213 | F | NLFLT | Helix |

| 228 (active site ligand) | H | LGHSS | Loop |

| 229 | S | GHSSD | Loop |

| 236 | M | AVMFP | Loop |

| 241 | K | TYKYV | Loop |

| 254 | D | ADDIR | Helix |

Table 2. Residues with missing NH resonances in the GFP-R5 1H-15N solid state NMR experiment.

| Residue No. | Residue Type | Flanking sequences | Secondary structure Element |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | L | EELFT | Helix |

| 37 | A | GDATY | Loop |

| 83 | F | HDFFK | Helix |

| 97 | T | ERTIS | Strand |

| 104 | G | DDGNY | Loop |

| 110 | A | TRAEV | Strand |

| 129 | D | GIDFK | Loop |

| 130 | F | IDFKE | Loop |

| 157 | Q | DKQKN | Helix |

| 167 | I | FKIRH | Strand |

| 173 | D | IEDGS | Loop |

| 175 | S | DGSVQ | Loop |

| 185 | N | QQNTI | Strand |

| 194 | L | GVLLD | Loop |

| 200 | Y | NHYLS | Strand |

The resonances assignment reported in the bmrb under the accession code 566644 has been used for the interpretation of the spectra.

It is interesting to observe that, in line with a previous observation, the R5 tail does not appear in the spectrum, most probably because it is disordered and thus extremely broad, as observed by the Drobny’s group45. As a remark, while it is possible to observe it for the catMMP12-R5, the R5 tail could not be observed in GFP-R5 solution, under the experimental conditions at which assignment of the WT protein is available, i.e.: pH = 8 and T = 310 K, whereas it reappears at lower temperature, indicating exchange with the solvent in line with previous reports on intrinsically disordered proteins46,47.

The resolution between the two proteins varies quite significantly (240 Hz and 140 Hz 1H-linewidth for catMMP12-R5 and GFP-R5 respectively). On the one hand, this may suggest that the residual mobility of the entrapped protein is different in the two cases, yielding a different averaging of the dipolar interaction; on the other hand this could reflect different degrees of static disorder or different anisotropic bulk magnetic susceptibility as caused by different silica particle size48. However it is important to observe that resolution is in a practically useful range even if the protein is completely protonated. This is an observation of remarkable importance because, on the one hand, 1H-detection based methods have been proven applicable and successful on a rather vast range of substrates33, also when fully protonated40,31,19; but, on the other hand, perdeuteration with more or less extensive back exchange is usually necessary to yield decoupling of the 1H dipolar network33,49. Thus, the remarkably sharp lines observed in the present study on fully protonated proteins guarantees, at least for a preliminary step, to use a relatively inexpensive sample, instead of resorting to the more expensive deuterated samples.

Overall, the present approach presents a number of advantages with respect to the approach based on the comparison of 13C-13C correlation maps. Brilliant discussion of the advantages of moving to smaller volumes50 and 1H detection33 has been provided, and the solid-state NMR rotor technology is progressing fast38, so we will only briefly recapitulate the specific advantages in the present case. First of all, the amount of sample needed is far smaller, yielding a reduction in the sample cost. The comparison here reported is based on the catMMP12-R5 sample, which has an encapsulation efficiency of 1.2 nmol of protein per μmol of silica41. The total amount of sample for the current work is 3 mg, corresponding to the 1.7 μl of the rotor active volume of a 1.3 mm Bruker rotor; whereas for a 4 mm rotor with CRAMPS inserts, the amount of sample needed to fill a 50 μl volume was over 80 mg41. As we are referring to a protein composite, it is rather more instructive to compare the starting protein solutions. The starting protein solution for the sample used in the present work was 400 μl at 45 mg/mL concentration of 15N-labeled protein (estimated cost 100 €, not including manpower), whereas the protein solution used for the sample preparation in reference41 was 2 mL at 45 mg/mL concentration of 13C15N protein (estimated cost 900 €, not including manpower), which corresponds to an order of magnitude difference in sample cost.

Another important point is the amount of measurement time that is needed: a 1H-start/1H detect experiment is expected to be roughly a factor 2.5 more sensitive than a 1H-start-13C detect experiment, neglecting relaxation effects and assuming 100% efficiency in each transfer step; the amount of experiments to be acquired in the indirect detection is about a factor 6 smaller and the full-rotor sensitivity of a solenoid coil (including the higher efficiency but also the reduction of sample) on passing from a 4 mm to a 1.3 mm rotor is roughly reduced by a factor 9.5 51,50, which would yield about a factor 2 increase in sensitivity, corresponding to about a factor 4 reduction in experiment time, thus in experiment price. These consideration are qualitatively reflected in the present case, as we find that the 1H-15N HSQC experiment could be acquired in 10 h 36′ for catMMP12-R5 in the current setup, whereas the 13C-13C DARR experiment reported in reference41 was acquired in 45 h 31′. Considering the price of access to high-field NMR solid-state instrumentation, the 1H-detection-based approach is about 80% cheaper than the 13C-detection based approach.

It is of remarkable importance that the 13C-13C transfers is likely to be differently efficient between the solution and the solid, resulting in a less straightforward interpretation of the spectral fingerprint of the molecule. Finally, 1H is much more sensitive to changes in the local environment.

In conclusion, we here demonstrate that enzymes entrapped in bioinspired silica can be studied by 1H-detected solid-state NMR, using a total sample of about 3 mg (including the silica matrix), as compared to previous studies where a larger amount of protein was used; and we were able to show that structural integrity is maintained.

It is expected that a) this approach will make it easier to screen for reaction conditions and/or substrates on a lower amount of sample and in a shorter time, and b) that the use of extensive deuteration will make it possible to perform assignment and structure calculations on a single SSNMR sample, without resorting to solution NMR, although at the price of increased sample production costs.

Methods

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy

All spectra were acquired with a Bruker AvanceIII spectrometer operating at 850 MHz 1H larmor frequency, equipped with a 1.3 mm probehead tuned to 1H-29Si-15N. Samples were packed into Bruker 1.3 mm zirconia rotors, centerpacked with KFM inserts (3 μl total volume) to avoid dehydration. Sample packing was performed with a ultracentrifugal device (courtesy of Bruker Biospin)52. Sample rotation was regulated to 60 kHz via a commercial Bruker MAS II pneumatic unit, and temperature was regulated to 240 K at stator inlet, roughly corresponding to 300 K at the sample. Pulses were 2.5 μs for 1H, 3.5 μs 15N. Optimal interscan delays are reported along with the spectra. During 15N evolution SWfTPPM53,54,55,56 decoupling was applied at 25 kHz. Water suppression was achieved by a 300 ms MISSISSIPPI pulse train at 25 kHz applied during a z-filter period when the magnetization is stored on 15N29,57. In the solid state HSQC experiment29, the polarization transfer steps between different nuclei is accomplished via cross-polarization (CP)58. The first CP step, which drives the magnetization from all protons to the nitrogen spins is 1.2-15 ms long; the second step, which must be as short as possible to be specific and not dominated by spin-diffusion, was kept at 300 μs.

Solution-state NMR spectroscopy

Experiments were performed on samples of the 15N isotopically enriched catalytic domain of MMP-12 fused with R5 peptide (catMMP12-R5) at protein concentration of 0.90 mM in water buffered solution (20 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM ZnCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, 200 mM AHA). The protein was inhibited with NNGH (N-Isobutyl-N-(4-methoxyphenylsulfonyl)glycyl hydroxamic acid) to reproduce the experimental conditions used in previous studies18,42,59,60,61. The same experiments were performed on GFP fused with R5 peptide (GFP-R5) at protein concentration of 0.35 mM in water buffered solution (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 300 mM NaCl). The spectrum of catMMP12-R5 was recorded on a Bruker DRX 500 spectrometer equipped with triple-resonance CryoProbe, and temperature was set to 298 K. The spectrum of GFP-R5 was recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 600 spectrometer equipped with a triple resonance room temperature probe, and temperature was set to 310 K. Spectra were processed with the Bruker TOPSPIN software packages and analyzed with the program CARA (Computer Aided Resonance Assignment, ETH Zurich).

Protein expression and purification

The catalytic domain of MMP-12 (catMMP12) has been expressed as fusion protein with a R5 peptide at the C-terminus as already described62.

pET-21a constructs encoding GFP-R5, sequence given below, were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells which were subsequently cultured in 15N-labelled minimal medium (M9). Cells were grown at 310 K, until OD 0.6–0.8 and subsequently induced with IPTG (isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside) with a final concentration of 0.5 mM for 5 h.

GFP-R5 was then extracted from harvested cells by sonication and subsequent ultra-centrifugation (40 min, 40000 rpm). The protein was first purified from the crude extract with an anionic exchange column (Q-FF 16/10, A buffer: Tris 50 mM pH 8, B buffer: Tris 50 mM pH 8, NaCl 1 M). The GFP-R5 was finally purified with gel filtration using a Superdex 75 26/60 in Tris 50 mM, NaCl 300 mM, pH 8. The concentrations of NaCl was reduced to 50 mM for the preparation of entrapped samples for ssNMR experiments.

The sequence of the GFP-R5 is:

1 MGKVSKGEEL FTGVVPILVE LDGDVNGHKF SVSGEGEGDA TYGKLTLKFI

51 CTTGKLPVPW PTLVTTFGYG LQCFARYPDH MKQHDFFKSA MPEGYVQERT

101 IFFKDDGNYK TRAEVKFEGD TLVNRIELKG IDFKEDGNIL GHKLEYNYNS

151 HNVYIMADKQ KNGIKVNFKI RHNIEDGSVQ LADHYQQNTP IGDGPVLLPD

201 NHYLSTQSAL SKDPNEKRDH MVLLEFVTAA GITLGMDELY K(GSASGGGGS)

251 [SKKSGSYSGS KGSKRRIL]

brackets indicate a linker that connects the protein to the R5 peptide, square brackets denote the R5 sequence (S201-L220 from sil1P from C. fusiformis).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ravera, E. et al.1H-detected solid-state NMR of proteins entrapped in bioinspired silica: a new tool for biomaterials characterization. Sci. Rep. 6, 27851; doi: 10.1038/srep27851 (2016).

Figure 3.

(A) The X-ray structure of GFP (2WUR43, which does not carry the R5 fusion) showing the charged residues in blue (positive) and red (negative). (B) The structure of GFP with the residues showing no signals shown in magenta.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, MIUR PRIN 2012SK7ASN, EC Contracts iNext No. 653706, Bio-NMR No. 261863, pNMR No. 317127 and IDPbyNMR No. 264257, and Instruct, part of the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures (ESFRI), through its Core Centre CERM, Italy. ER holds a FIRC triennial fellowship “Gino Mazzega and Guglielmina Locatello” (17941).

Footnotes

Author Contributions E.R., C.L. and M.F. designed the research; E.R., L.C., T.M. and A.L. performed the experiments; E.R., L.C., M.F. and C.L. interpreted the data; all authors wrote the manuscript.

References

- Kröger N., Deutzmann R. & Sumper M. Polycationic peptides from diatom biosilica that direct silica nanosphere formation. Science 286, 1129–1132 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kröger N., Deutzmann R. & Sumper M. Silica-precipitating Peptides from Diatoms THE CHEMICAL STRUCTURE OF SILAFFIN-1A FROM CYLINDROTHECA FUSIFORMIS. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26066–26070 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner S. & Dove P. M. An Overview of Biomineralization Processes and the Problem of the Vital Effect. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 54, 1–29 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Belton D. J., Patwardhan S. V., Annenkov V. V., Danilovtseva E. N. & Perry C. C. From biosilicification to tailored materials: Optimizing hydrophobic domains and resistance to protonation of polyamines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105, 5963–5968 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belton D. J., Deschaume O. & Perry C. C. An overview of the fundamentals of the chemistry of silica with relevance to biosilicification and technological advances. FEBS J. 279, 1710–1720 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior L. et al. Structure and function of the silicifying peptide R5. J. Mater. Chem. B (2015). doi: 10.1039/C4TB01679C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckarift H. R., Spain J. C., Naik R. R. & Stone M. O. Enzyme immobilization in a biomimetic silica support. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 211–213 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo C. W. P. et al. Novel nanocomposites from spider silk–silica fusion (chimeric) proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 9428–9433 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marner W. D., Shaikh A. S., Muller S. J. & Keasling J. D. Enzyme immobilization via silaffin-mediated autoencapsulation in a biosilica support. Biotechnol. Prog. 25, 417–423 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marner W. D., Shaikh A. S., Muller S. J. & Keasling J. D. Morphology of artificial silica matrices formed via autosilification of a silaffin/protein polymer chimera. Biomacromolecules 9, 1–5 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S. et al. Control of silicification by genetically engineered fusion proteins: Silk-silica binding peptides. Acta Biomater. 15, 173–180 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belton D. J., Mieszawska A. J., Currie H. A., Kaplan D. L. & Perry C. C. Silk-silica composites from genetically engineered chimeric proteins: materials properties correlate with silica condensation rate and colloidal stability of the proteins in aqueous solution. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids 28, 4373–4381 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canabady-Rochelle L. L. S. et al. Bioinspired silicification of silica-binding peptide-silk protein chimeras: comparison of chemically and genetically produced proteins. Biomacromolecules 13, 683–690 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieszawska A. J., Nadkarni L. D., Perry C. C. & Kaplan D. L. Nanoscale control of silica particle formation via silk-silica fusion proteins for bone regeneration. Chem. Mater. Publ. Am. Chem. Soc. 22, 5780–5785 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner C. C. & Becker C. F. W. Silaffins in Silica Biomineralization and Biomimetic Silica Precipitation. Mar. Drugs 13, 5297–5333 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon R. A. Enzyme Immobilization: The Quest for Optimum Performance. Adv. Synth. Catal. 349, 1289–1307 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Blanco R. M., Calvete J. J. & Guisán J. Immobilization-stabilization of enzymes; variables that control the intensity of the trypsin (amine)-agarose (aldehyde) multipoint attachment. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 11, 353–359 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Fragai M. et al. SSNMR of biosilica-entrapped enzymes permits an easy assessment of preservation of native conformation in atomic detail. Chem. Commun. 50, 421–423 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravera E. et al. NMR of sedimented, fibrillized, silica-entrapped and microcrystalline (metallo) proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 253, 60–70 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravera E. et al. Biosilica-Entrapped Enzymes Studied by Using Dynamic Nuclear-Polarization-Enhanced High-Field NMR Spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem 16, 2751–2754 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger Y., Gottlieb H. E., Akbey Ü., Oschkinat H. & Goobes G. Studying the Conformation of a Silaffin-Derived Pentalysine Peptide Embedded in Bioinspired Silica using Solution and Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Magic-Angle Spinning NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5561–5567 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantschke A. et al. Insight into the Supramolecular Architecture of Intact Diatom Biosilica from DNP-Supported Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 15069–15073 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif B. & Griffin R. G. 1H detected 1H,15N correlation spectroscopy in rotating solids. J. Magn. Reson. San Diego Calif 1997 160, 78–83 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevelkov V. et al. 1H Detection in MAS Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of Biomacromolecules Employing Pulsed Field Gradients for Residual Solvent Suppression⊥. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7788–7789 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevelkov V., Rehbein K., Diehl A. & Reif B. Ultrahigh resolution in proton solid-state NMR spectroscopy at high levels of deuteration. AngewChem IntEd Engl 45, 3878–3881 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D. H. et al. Proton-detected solid-state NMR spectroscopy of fully protonated proteins at 40 kHz magic-angle spinning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 11791–11801 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linser R., Bardiaux B., Higman V., Fink U. & Reif B. Structure calculation from unambiguous long-range amide and methyl 1H-1H distance restraints for a microcrystalline protein with MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5905–5912 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linser R. et al. Proton-Detected Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of Fibrillar and Membrane Proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 4508–4512 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M. J. et al. Fast resonance assignment and fold determination of human superoxide dismutase by high-resolution proton-detected solid state MAS NMR spectroscopy. Angew.Chem.Int.Ed. 50, 11697–11701 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M. J. et al. Structure and backbone dynamics of a microcrystalline metalloprotein by solid-state NMR. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 109, 11095–11100 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti A. et al. Backbone Assignment of Fully Protonated Solid Proteins by 1H Detection and Ultrafast Magic-Angle-Spinning NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 10756–10759 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M. J., Felli I. C., Pierattelli R., Emsley L. & Pintacuda G. Magic Angle Spinning NMR of Paramagnetic Proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 2108–2116 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet-Massin E. et al. Rapid Proton-Detected NMR Assignment for Proteins with Fast Magic Angle Spinning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12489–12497 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Pandey M. K., Nishiyama Y. & Ramamoorthy A. A Novel High-Resolution and Sensitivity-Enhanced Three-Dimensional Solid-State NMR Experiment Under Ultrafast Magic Angle Spinning Conditions. Sci. Rep. 5, 11810 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R. & Ramamoorthy A. Selective excitation enables assignment of proton resonances and 1H-1H distance measurement in ultrafast magic angle spinning solid state NMR spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 034201 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R. & Ramamoorthy A. Dynamics-based selective 2D 1H/1H chemical shift correlation spectroscopy under ultrafast MAS conditions. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 204201 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I., McGreevy K. S. & Parigi G. NMR in systems biology. (Wiley, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pandey M. K. et al. 1020 MHz single-channel proton fast magic angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 261, 1–5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroue K. H. et al. Proton-Detected Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of Bone with Ultrafast Magic Angle Spinning. Sci. Rep. 5, 11991 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D. H., Shah G., Mullen C., Sandoz D. & Rienstra C. M. Proton-Detected Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of Natural-Abundance Peptide and Protein Pharmaceuticals. Angew. Chem. 121, 1279–1282 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli T. et al. Atomic level quality assessment of enzymes encapsulated in bio-inspired silica. Chem. - Eur. J. 4, 425–432 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I. et al. Conformational variability of matrix metalloproteinases: Beyond a single 3D structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 5334–5339 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinobu A., Palm G. J., Schierbeek A. J. & Agmon N. Visualizing Proton Antenna in a High-Resolution Green Fluorescent Protein Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11093–11102 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan F., Stott K. & Jackson S. 1H, 15N and 13C backbone assignment of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). J. Biomol. NMR 26, 281–282 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehrich A. & Drobny G. Solid-State NMR Studies of Biomineralization Peptides and Proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 2136–2144 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil S. et al. NMR Spectroscopic Studies of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins at Near-Physiological Conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 11808–11812 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croke R. L., Sallum C. O., Watson E., Watt E. D. & Alexandrescu A. T. Hydrogen exchange of monomeric α-synuclein shows unfolded structure persists at physiological temperature and is independent of molecular crowding in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 17, 1434–1445 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl W. L. & Vanderhart D. L. Measurement of 13C chemical shifts in solids. J. Magn. Reson. 1969 48, 35–54 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Asami S. & Reif B. Proton-Detected Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy at Aliphatic Sites: Application to Crystalline Systems. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 2089–2097 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers J. P., Chevelkov V. & Lange A. Progress in correlation spectroscopy at ultra-fast magic-angle spinning: basic building blocks and complex experiments for the study of protein structure and dynamics. Solid State NuclMagnReson 40, 101–113 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill S. A., Gor’kov P. L., Struppe J., Brey W. W. & Long J. R. Optimizing ssNMR experiments for dilute proteins in heterogeneous mixtures at high magnetic fields. Magn. Reson. Chem. 45, S209–S220 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I. et al. On the use of ultracentrifugal devices for sedimented solute NMR. J.Biomol.NMR 54, 123–127 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur R. S., Kurur N. D. & Madhu P. K. Swept-frequency two-pulse phase modulation for heteronuclear dipolar decoupling in solid-state NMR. Chem. Phys. Lett. 426, 459–463 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Thakur R. S., Kurur N. D. & Madhu P. K. An experimental study of decoupling sequences for multiple-quantum and high-resolution MAS experiments in solid-state NMR. Magn. Reson. Chem. 46, 166–169 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur R. S., Kurur N. D. & Madhu P. K. An analysis of phase-modulated heteronuclear dipolar decoupling sequences in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Magn. Reson. 193, 77–88 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhu P. K. Heteronuclear Spin Decoupling in Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance: Overview and Outlook. Isr. J. Chem. 54, 25–38 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D. H. & Rienstra C. M. High-performance solvent suppression for proton detected solid-state NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 192, 167–172 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines A., Gibby M. G. & Waugh J. S. Proton enhanced NMR of dilute spins in solids. J Chem Phys 59, 569–590 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Balayssac S. et al. Solid-state NMR of matrix metalloproteinase 12: an approach complementary to solution NMR. ChemBioChem 8, 486–489 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I. et al. High-Resolution Solid-State NMR Structure of a 17.6 kDa Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1032–1040 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchinat C., Parigi G., Ravera E. & Rinaldelli M. Solid state NMR crystallography through paramagnetic restraints. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 5006–5009 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I., Fragai M., Luchinat C., Melikian M. & Venturi C. Characterisation of the MMP-12-Elastin Adduct. Chem. - Eur. J. 15, 7842–7845 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]