Abstract

Calnexin (Cnx) and calreticulin (Crt), which are important chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), participate in the folding and quality control of client proteins. Cnx and Crt identified from Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) are designated as EsCnx and EsCrt, respectively. EsCnx and EsCrt are expressed in the hemocyte, hepatopancrea, gill, and intestine at the mRNA and protein level. Immunofluorescence analysis indicated that EsCnx and EsCRT are located in the ER. Moreover, the mRNA and protein expression levels of EsCnx and EsCrt were altered by challenge with lipopolysaccharides (LPS), peptidoglycans (PGN), Staphyloccocus aureus, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Recombinant EsCnx and EsCrt (rEsCnx and rEsCrt, respectively) proteins can bind to various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as to different polysaccharides (LPS and PGN). rEsCnx and rEsCrt assisted in the clearance of V. parahaemolyticus in vivo, and the clearance efficiency was impaired after silencing of EsCnx and EsCrt. Our results suggest that the two ER proteins are involved in anti-bacterial immunity in E. sinensis.

Chaperones perform critical roles in various physiological processes, such as in promotion of cell survival, irreversible aggregation of newly synthesized proteins, prevention of misfolding, maintenance of the unfolded conformation of newly synthesized polypeptides, binding to non-native proteins during cellular stress responses, assembly of large proteins and multiprotein complexes, intracellular signaling, transcription, and differentiation1,2,3. Calnexin (Cnx) and calreticulin (Crt) are related molecular chaperone proteins localized in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER); these proteins are the most extensively studied glycoprotein-specific chaperones4. The ER is a dynamic organelle in cells and plays a wide array of functions in the synthesis of membrane and secretory proteins, as well in regulating protein folding, post-translational modification of membrane-associated proteins, secretion, and degradation5,6. This organelle provides an oxidizing environment that, along with chaperone and co-chaperone proteins, induces the formation of disulfide bonds, appropriate folding of nascent glycoproteins, and prevention of improper folding of proteins7. As marker proteins, Cnx and Crt preferentially interact with non-native proteins through N-linked oligosaccharide moieties to form relatively stable complexes in the ER8,9; this interaction persists until the proteins are properly folded or until misfolded proteins are degraded10,11.

Cnx, a lectin chaperone that was first isolated from mouse, is transiently associated with partly folded MHC class I molecules12; Cnx was subsequently cloned from the liver cDNA library of humans in 199113. Cnx is also associated with incomplete forms of MHC class I molecules, T-cell receptors, and membrane immunoglobulins14,15. In addition, Cnx, with a molecular mass of approximately 90 kDa, is a non-glycosylated type I membrane protein present in many species16. The protein structure of Cnx contains three functionally distinct domains: a large ER luminal domain, a transmembrane domain, and an ER-retention motif in the cytoplasmic tail13. The amino acid sequences of Cnx in plants and animals contain conserved regions in the middle parts and highly diverse regions in the N- and C-termini17. Cnx and its soluble homolog Crt constitute a dedicated maturation system, known as the Cnx/Crt cycle, which mainly promotes correct folding and oligomerization of newly synthesized glycoproteins before their export from the ER18,19. Furthermore, Cnx plays a role in Ca2+ regulation20, phagocytosis (a phylogenetically conserved process)21, and cell sensitivity to apoptosis in the ER22.

Crt, a highly conserved ER luminal resident protein, plays important roles in quality control, Ca2+ homeostasis, lectin-like chaperoning, gene regulation, cell adhesion, wound healing, cancer, and autoimmunity23,24, as well as in various oxidative stress responses to hydrogen peroxide, hypoxic injury, and iron overload25,26,27. Crt not only exists inside and outside of the ER lumen but also on the cell surface or extracellular matrix28,29. Crt was first isolated from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of rabbit muscle cells and identified as a high affinity Ca2+-binding protein30; subsequent isolation of this protein in mouse indicated that Crt contains the ER retention/retrieval signal KDEL (Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu) sequence at the C-terminus and is primary located in the lumen of the ER31. Numerous Crt genes have been isolated from diverse organisms32. In nearly all eukaryotes, Crt contains several structural and functional domains, including an N-domain, which is a protein-interacting domain, as well as proline-rich (P) and C domains, which interact with Ca2+ (refs 33,34). Crt regulates Ca2+ levels by controlling the signaling and homeostasis of this ion and acts as a protein-folding chaperone by forming a complex with the ER protein 57 (ERp57)32,35. In addition, Crt affects biological processes, including growth, reproduction, molting, the immune system, apoptosis, and stress responses23,36.

The roles of molecular chaperones in modulating immune functions have received increased research attention. In this study, EsCnx and EsCrt were identified from crabs, and their potential functions in innate immunity were investigated. Data obtained in this study will elucidate the roles of Cnx and Crt in crab innate immunity.

Results

cDNA cloning and sequence analysis

The 3175-bp full-length cDNA of EsCnx encodes a polypeptide of 598 amino acids; this peptide possesses a predicted molecular weight of 68 kDa and a theoretical isoelectric point of 4.50 (Fig. 1SA). EsCrt is 1741-bp long and encodes a protein of 406 amino acids; the calculated molecular weight and theoretical isoelectric point of EsCrt are 46.8 kDa and 4.29, respectively.

BLASTP search and multiple sequence alignment showed that EsCnx exhibits sequence similarity to other reported crustacean Cnxs, such as 76% identity to that of Marsupenaeus japonicas (AIF71174.1) (Fig. 2SA). The deduced amino acid sequence of EsCrt shares significant homology with other known Crts, such as 92% similarity to that of Scylla paramamosain (AEN94572.1) (Fig. 2SB). The constructed phylogenetic tree showed that EsCnx, M. japonicas MjCnx, and Penaeus monodon PmCnx are clustered into one subgroup (Fig. 3S). Meanwhile, EsCrt and nine Crts from other crustaceans and Culex quinquefasciatus are clustered into one group (Fig. 4S).

Tissue distribution of EsCnx and EsCrt and immunofluorescence assay

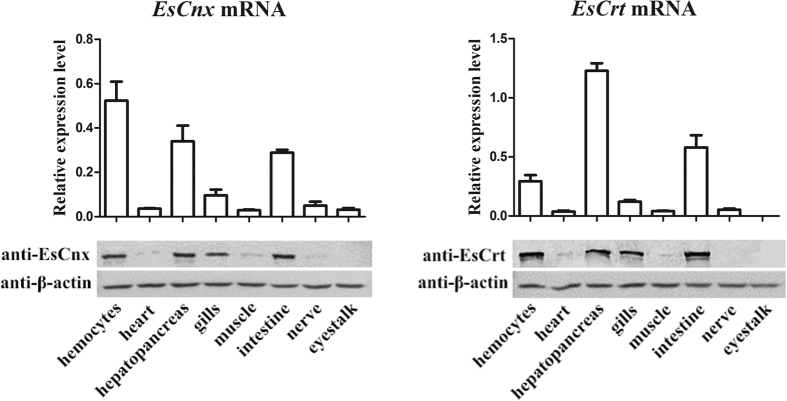

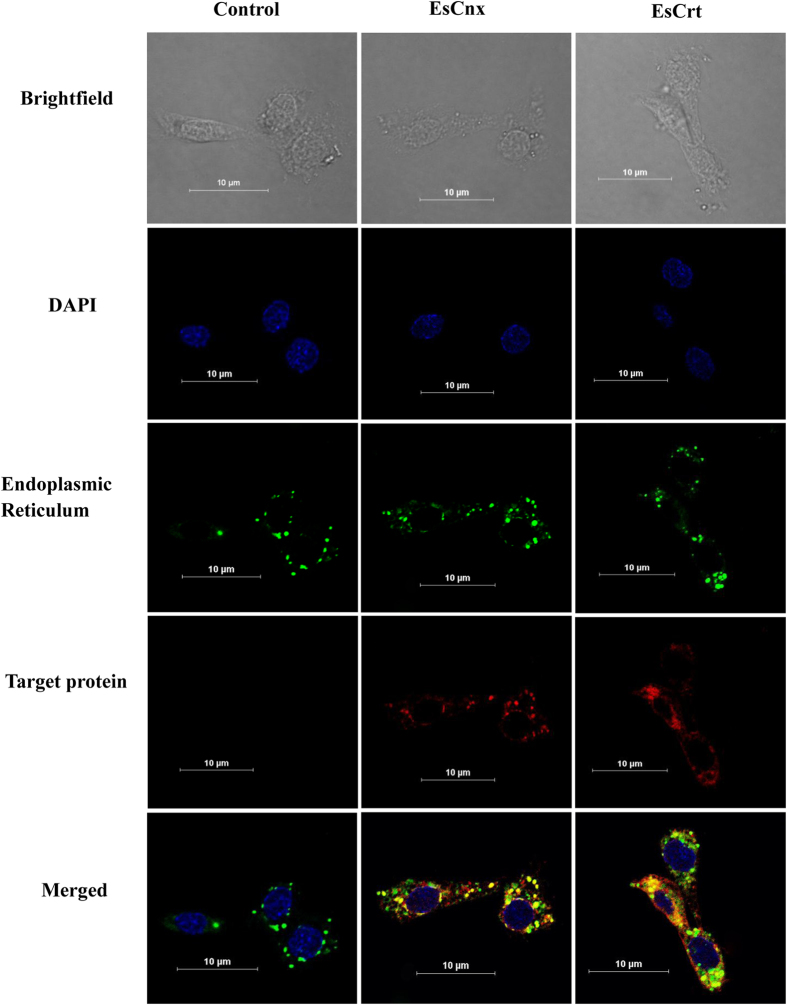

EsCnx and EsCrt mRNAs were highly expressed in the hemocyte, hepatopancrea, gill, and intestine (Fig. 1). The highest expression level of EsCnx was detected in hemocytes, followed by hepatopancreas and intestines. EsCrt was mainly expressed in the hepatopancreas, intestine, and hemocytes of healthy crabs. Western blot analysis showed the presence of EsCnx and EsCrt in hemocytes, hepatopancreas, gills, and intestine (Fig. 1). Furthermore, immunofluorescence assay combined with confocal microscopy analysis confirmed that EsCrt and EsCnx were located in the ER (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Tissue distributions of EsCnx and EsCrt at the mRNA level (above) revealed by SYBR Green qRT-PCR and protein expression level (below) revealed by western blot.

Vertical bars represent mean ± S.E. (N = 5) for each tissue. Each bar represents the mean value from five determinations with standard error.

Figure 2. Intracellular localization of EsCrt and EsCnx in crab cells.

Hemocytes were stained for EsCrt or EsCnx using rabbit anti-EsCrt antibody (1:1000) or anti-EsCnx (1:1000). DAPI was used to stain the nucleus. DiOC6(3) 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide is a green fluorescent membrane dye used for staining the endoplasmic reticulum.

Analysis of protein and mRNA expression patterns of EsCnx and EsCrt after challenge with polysaccharides and microorganisms

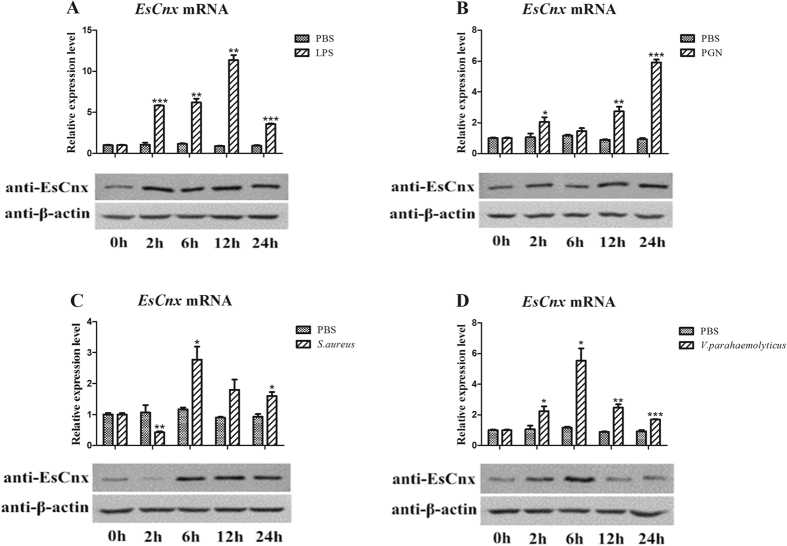

When crabs were injected with lipopolysaccharides (LPS), the mRNA expression levels of EsCnx from 2 h to 12 h were significantly higher than those in the untreated control and then decreased at 24 h (Fig. 3A). After 2 h of peptidoglycan (PGN) challenge, EsCnx was initially upregulated, returned to its original level at 6 h, and then increased at 12 and 24 h (Fig. 3B). The transcript expression of EsCnx was initially downregulated 2 h after challenge with Staphylococcus aureus, reached the highest level at 6 h, and gradually decreased from 12 h to 24 h (Fig. 3C). After challenge with Vibrio parahaemolyticus, the EsCnx mRNA expression level gradually increased within 2 h, peaked at 6 h, and then decreased at 12 and 24 h (Fig. 3D). Moreover, the protein expression pattern of EsCnx was similar to that of mRNA expression upon challenge with LPS (Fig. 3A), PGN (Fig. 3B), S. aureus (Fig. 3C), and V. parahaemolyticus (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

EsCnx mRNA and protein expression profile in hepatopancreas after LPS (A), PGN (B), S. aureus (C), and V. parahaemolyticus (D) challenge as measured by qRT-PCR and western blot. The GAPDH gene was used as internal control to calibrate the cDNA template of all samples. Vertical bars represent mean ± S.E. (N = 5). Each bar represents the mean value of five determinations with standard deviation. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) compared with the control. The β-actin was used as internal control to calibrate the protein template of all samples.

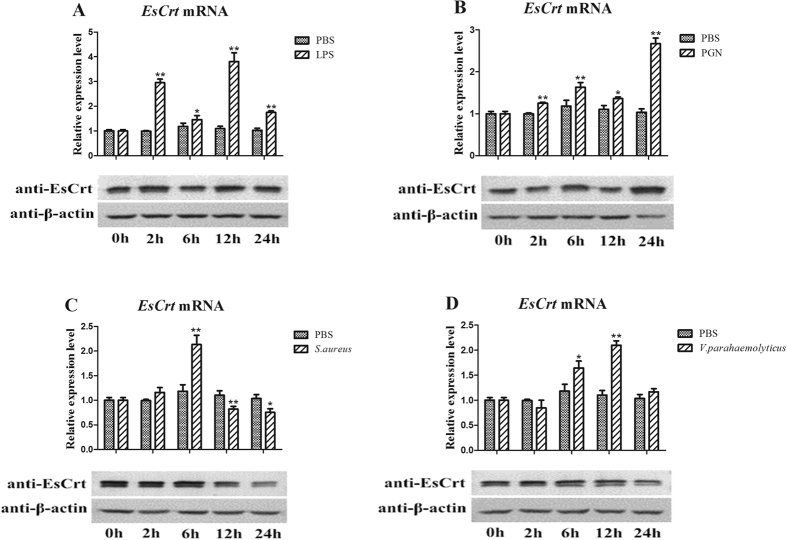

EsCrt was rapidly upregulated 2 h after LPS challenge, decreased at 6 h, increased at 12 h, and was finally downregulated again at 24 h (Fig. 4A). The EsCrt protein level did not change within 2–12 h after the LPS challenge (Fig. 4A). After 2–6 h of the PGN challenge, EsCrt mRNA and EsCrt protein expression levels were gradually upregulated, decreased at 12 h, and finally reached the highest levels (Fig. 4B). After 6 h of S. aureus challenge, EsCrt transcription peaked and then decreased from 12 h to 24 h (Fig. 4C). Upon S. aureus challenge, the protein expression pattern of EsCrt was similar to that of mRNA expression (Fig. 4C). After V. parahaemolyticus challenge, EsCrt expression increased from 6 h to 12 h and then recovered to the normal level (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, the protein expression level of EsCrt did not evidently change upon V. parahaemolyticus challenge (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

EsCrt mRNA and protein expression profile in the hepatopancreas after LPS (A), PGN (B), S. aureus (C), and V. parahaemolyticus (D) challenge as measured by qRT-PCR and western blot. GAPDH gene was used as an internal control to calibrate the cDNA template for all of the samples. Vertical bars represent mean ± S.E. (N = 5). Each bar represents the mean value of five determinations with standard deviation. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) compared with the values of control. The β-actin was used as internal control to calibrate the protein template of all samples.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

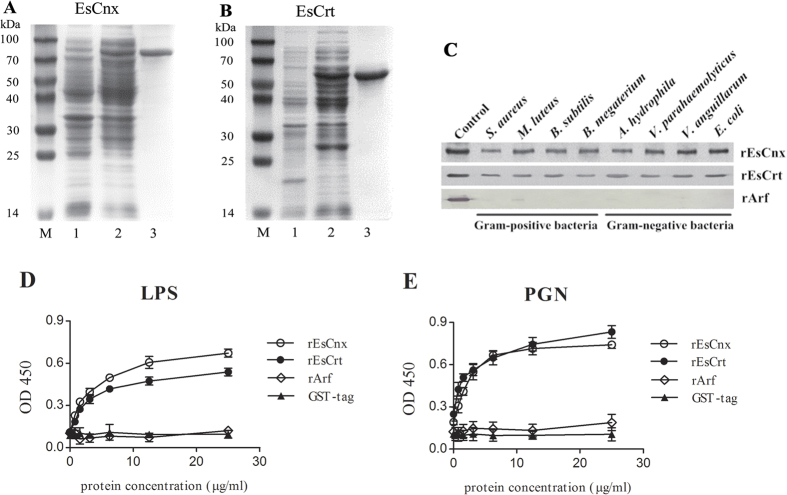

Figure 5A shows a detected band with a molecular weight of approximately 70 kDa, which is consistent with the predicted molecular weight of the Crt region of EsCnx (MW: 43.1 kDa) with a 26-kDa GST tag. EsCrt bearing the GST tag was approximately 62 kDa (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis of rEsCnx (A) and rEsCrt (B). Lane M: protein molecular weight standards (kDa); lane A1: negative control for rEsCnx (without induction); lane A2: IPTG-induced rEsCnx; lane A3: purified rEsCnx; lane B1: negative control for rEsCrt (without induction); lane B2: IPTG-induced rEsCrt; and lane B3: purified rEsCrt. (C) Direct binding of rEsCnx and rEsCrt proteins to microorganisms (S. aureus, M. luteus, B. subtilis, B. megaterium, A. hydrophila, V. parahaemolyticus, V. anguillarum, and E. coli). The microorganisms were incubated with rEsCnx or rEsCrt and then washed four times with TBS. ELISA assay was employed to detect the binding of rEsCnx (D) and rEsCrt (E) to LPS and PGN using antiserum against rEsCnx and rEsCrt. All assays were repeated three times.

Microbial and carbohydrate binding of rEsCnx and rEsCrt

The bacterial binding assay showed that rEsCrt can bind to all tested microorganisms, including four kinds of Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus, M. luteus, B. subtilis, and Bacillus megaterium) and four kinds of Gram-negative bacteria (Aeromonas hydrophila, V. parahaemolyticus, Vibrio anguillarum, and Escherichia coli). rEsCnx weakly bound to S. aureus and A. hydrophila but strongly bound to the six other microorganisms (Fig. 5C). No visible binding was detected in the negative control.

rEsCnx and rEsCrt demonstrated binding activity to PGN or LPS. The binding activity of rEsCnx to LPS was higher than that of rEsCrt; whereas the binding activity of rEsCrt to PGN was higher than that of rEsCnx. The binding ability of the proteins was found to be dose dependent (Fig. 5D,E). For the control, rArf and GST proteins did not bind to LPS or PGN.

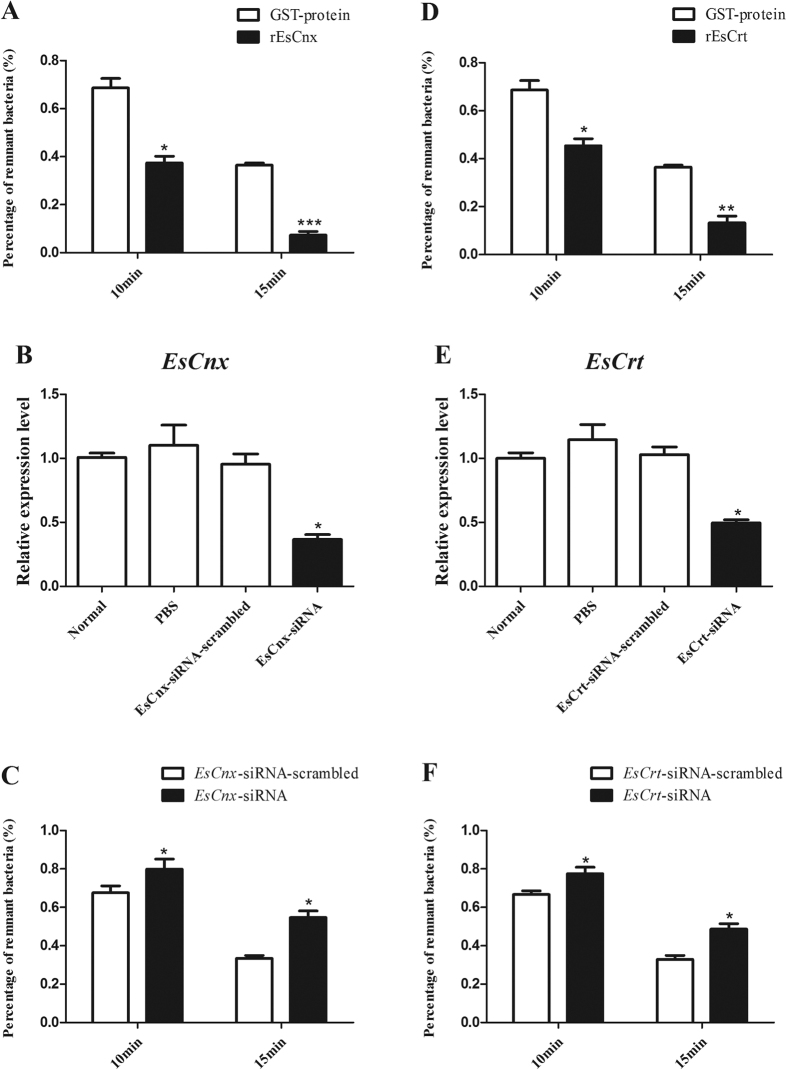

Effect of rEsCnx and rEsCrt on the clearance of V. parahaemolyticus

Given that rEsCnx and rEsCrt can bind to the crab pathogen V. parahaemolyticus, we determined whether or not rEsCnx and rEsCrt affect the bacterial clearance rate in crabs. The bacterial clearance experiment showed that V. parahaemolyticus was cleared more rapidly in the hemolymphs of rEsCnx and rEsCrt injection groups compared with rArf and GST control groups (10 and 15 min, respectively) (Fig. 6A,D).

Figure 6.

Effect of rEsCnx and rEsCrt in V. parahaemolyticus clearance activities in crab. rEsCnx (A) or rEsCrt (D) enhanced the clearance of V. parahaemolyticus in vivo. V. parahaemolyticus clearance assay was conducted by pre-coating the injected bacteria with rEsCnx, rEsCrt, or GST-tag protein. The number of remnant bacteria was counted at 2, 10, or 15 min post-injection. The percentage of remnant bacteria was calculated as follows: percentage of remnant bacteria = (number of bacteria at 10 min or 15 min/number of bacteria at 2 min) × 100. RNAi of EsCnx (B) or EsCrt (E) suppressed bacterial clearance in hemocytes. The mRNA transcription level of EsCnx 24 h after injection of EsCnx-siRNA or EsCnx-siRNA-scrambled, as revealed by qRT-PCR analysis. The mRNA transcription level of EsCrt 24 h after injection of EsCrt-siRNA or EsCrt-siRNA-scrambled was revealed by qRT-PCR. The clearance rate of V. parahaemolyticus in crabs was impaired by silencing EsCnx (C) or EsCrt (F) through RNAi. Two groups of crabs were injected with EsCnx-siRNA or EsCrt-siRNA-scrambled (control), and clearance assay was conducted 24 h post-injection.

Clearance assays were also conducted after knockdown of EsCnx or EsCrt. EsCnx or EsCrt expression significantly decreased 24 h after injection of EsCnx-siRNA or EsCrt-siRNA (Fig. 6B,E); moreover, the clearance rate of V. parahaemolyticus in the crab significantly decreased after knockdown of EsCnx or EsCrt (Fig. 6CF). These findings indicate that EsCnx and EsCrt play important functions in clearing V. parahaemolyticus.

Discussion

Cnxs and Crts, which are important chaperones in the ER, are involved in translocation, protein folding, and quality control of newly synthesized polypeptides4. The roles of Cnxs and Crts in the innate immune system have been investigated in crustaceans. For instance, Crt was detected in the ovary and in various molting stages of Chinese white shrimp (Fenneropenaeus chinensis). When a host is exposed to heat shock or challenged by white spot syndrome virus (WSSV), Crt is rapidly cleaved and the shrimp initiates a defense reaction against the stimuli32. In crayfish, the C1q-binding proteins Crt and gC1qR, which are highly conserved ubiquitous proteins, can respond to viral infection by forming a complex in the cytoplasm, thereby preventing apoptosis37. Another Crt associated with immune defenses against V. anguillarum and WSSV was purified from the hemocytes of ridge tail white prawn (Exopalaemon carinicauda)38. A novel MjCnx protein was also detected in the cytoplasm and on the membrane of hemocytes in kuruma shrimp (M. japonicas); MjCnx protein not only enhances the clearance of V. anguillarum in vivo but also promotes phagocytic efficiency of hemocytes39. However, information on the function of Cnx and Crt in crab immunity remains unavailable40. Detecting Cnxs and Crts from crabs and investigating their immune mechanism can elucidate the functional diversity of crustacean Cnxs and Crts.

In this study, EsCnx and EsCrt were identified from Eriocheir sinensis. EsCnx and EsCrt were primarily distributed in hemocytes, hepatopancreas, and intestine; the expression levels of these proteins were altered by challenge with polysaccharides and microorganisms. Moreover, the mRNA transcripts of MjCnx from M. japonicas39 and EcCrt from E. carinicauda38 were upregulated in several tissues challenged with V. anguillarum. Hemocytes are important tissues involved in crustacean immunity and comprise many immune-related genes41. As the counterpart of the insect fat body and mammalian liver, the hepatopancreas is important for the humoral immune responses of crustaceans42. The arthropod alimentary tract is the first defense barrier against pathogen invasion43,44; furthermore, the intestine, as a crucial part of the alimentary canal, plays an essential role in crab immunity. These results suggest that EsCnx and EsCrt are involved in crab antibacterial immunity.

Since the discovery of Cnx and Crt in mammals12,30, the functions of these two proteins have been the subject of most studies. Cnx is a lectin chaperone, whereas Crt is a lectin-like chaperone12,23. In addition to the chaperone activity, Cnx and Crt also have nonchaperone fuctions such as phagocytosis and lectin activity21,39. In this study, crab rEsCnx and rEsCrt showed the lectin activities of binding diverse bacteria and several polysaccharides. The lectin activities of shrimp rMjCnx were also reported39. Lectins, which are pattern-recognition proteins, play crucial functions in recognizing and eliminating pathogens in innate immunity45. So, crab rEsCnx and rEsCrt may play an important role in recognizing and binding bacteria; this phenomenon is the first line of innate immune defense46,47.

Furthermore, we assumed that rEsCnx and rEsCrt can accelerate clearance of invading V. parahaemolyticus, which is a Gram-negative bacterium and an extremely virulent and prevalent pathogen that affects crab aquaculture48. Overexpression of rEsCnx or rEsCrt can enhance clearance of V. parahaemolyticus in vivo in crabs and the clearance of bacteria was impaired after knockdown of EsCnx or EsEsCrt. The rMjCnx also accelerate the removal of bacteria in shrimp39. It was also reported that rMjCnx can promote phagocytosis of bacteria39. Invertebrates exhibit effective innate immune responses, including humoral and cellular responses49. Cellular immune responses involve different types of hemocytes, which participate in pathogen clearance through phagocytosis of microorganisms50. Recognition of pathogen is the first step of phagocytosis and it needs the participation of receptors. In human, three types of receptors including pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), opsonic receptors, and apoptotic corpse receptors are involved in phagocytosis51. The broad binding spectrum of rEsCnx and rEsCrt toward diverse bacteria and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) suggest that EsCnx and EsCrt may serve as phagocytic receptors.

In conclusion, this work is the first to characterize EsCnx and EsCrt isolated from E. sinensis. EsCnx and EsCrt expression levels are regulated by polysaccharide or bacterial challenge. Moreover, rEsCnx and rEsCrt proteins not only can bind to various bacteria and different polysaccharides (LPS and PGN) but also facilitate clearance of V. parahaemolyticus in crabs. Our results suggest that EsCnx and EsCrt are involved in anti-bacterial immunity in E. sinensis.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of full-length cDNAs of EsCnx and EsCrt

Two expressed sequence tags were obtained from the hepatopancreas of E. sinensis by using Illumina’s Solexa Sequencing Technology in the Chinese National Human Genome Center in Shanghai. Two pairs of gene-specific primers (EsCnx-F and EsCnx-R, as well as EsCrt-F and EsCrt-R) were designed based on the obtained cDNA sequences of EsCnx and EsCrt to clone their full-length sequences (the primer sequences are shown in Table 1).

Table 1. Primer sequences used in this study.

| Primers name | Sequences (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| EsCnx-F | GTGACTGACAATACGGCTGAGGCTGACC |

| EsCnx-R | CCACTCCTTCCTTCTTTGCCTGTGACTTG |

| EsCrt-F | CCCCGAGTACACCCCTGACACAGAAATCT |

| EsCrt-R | GCTCTTCACCTGCCACAAGTCCAAACCGA |

| EsCnx-RT-F | AAATGGATGGTGAATGGGAGGC |

| EsCnx-RT-R | TTGGGGATGGTGCGAGGTT |

| EsCrt-RT-F | GGAGAGCAAGGAGGATGAGGAG |

| EsCrt-RT-R | AAGGGGATTGACTGAGGAAAGATTA |

| EsGAPDH-RT-F | CTGCCCAAAACATCATCCCATC |

| EsGAPDH-RT-R | CTCTCATCCCCAGTGAAATCGC |

| EsCrt-ex-F | CCGGAATTCGCTTATGTCATGGAAACATTT |

| EsCrt-ex-R | TACTCAGCGGCCGCTCCACAATAAGGTTATCAAAAAGG |

| EsCrt-ex-F | CCGGAATTCGTGTTCTTCCAGGAGACCTTC |

| EsCrt-ex-R | TACTCAGCGGCCGCTCAATGAGGAAGTTGTCGAA |

| EsCnx-siRNA | GCTGGCTGCAGACACTTAT |

| EsCnx-siRNA-scrambled | ATTGCAGCTGGCAAGCCTT |

| EsCrt-siRNA | GGTGTGAAAGAACCACAAT |

| EsCrt-siRNA-scrambled | TGAGGACATGACATGAAAC |

EcoR I and Not I sites are underlined.

Sequence analysis

The cDNA sequences and deduced protein sequences of EsCnx and EsCrt were analyzed using the BLAST algorithm of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and the Expert Protein Analysis System (http://web.expasy.org/translate/). Signal peptide and putative domains were predicted using the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). Molecular weights and isoelectric points of EsCnx and EsCrt were determined using ExPASy (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/). Moreover, MEGA 5.05 was used to produce an unrooted phylogenetic tree based on the deduced full amino acid sequences of EsCnx and EsCrt and other related proteins by using the neighbor-joining method52. One thousand bootstraps were selected for the neighbor-joining tree to assess reliability. MEGA 5.05 and GENDOC were also used to perform multiple sequence alignments.

Animals, polysaccharides, and microbes

Adult Chinese mitten crabs were purchased from a wet market (Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China) and housed in filtered, aerated freshwater at 20–25 °C for a week before processing. LPS (E. coli Serotype 055:B5) and PGN (M. luteus) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). S. aureus, M. luteus, B. subtilis, B. megaterium, A. hydrophila, V. parahaemolyticus, V. anguillarum, and E. coli were purchased from the Microbial Culture Collection Center (Beijing, China) and grown in LB broth at 37 °C.

Tissue collection and challenge with polysaccharides and microorganisms

Various tissues (hemocytes, heart, hepatopancreas, gills, muscle, intestine, nerve, and eyestalk from five adult crabs as parallel samples) were collected to determine the tissue distribution of EsCnx and EsCrt transcripts. The hemolymph was withdrawn using a 1 mL sterile syringe containing an equal volume of anticoagulant solution (ACD-B)53. The samples were immediately centrifuged at 800 × g at 4 °C for 15 min to collect hemocytes. A total of 150 crabs in the bacteria-challenged groups were used in the experiment. The crabs were injected with 50 μL of LPS (0.5 μg/μL), PGN (0.5 μg/μL), live S. aureus (3 × 107 cells), or V. parahaemolyticus (3 × 107 cells) in PBS. Five individual crabs were randomly sampled at 2, 6, 12, and 24 h in the challenge groups during the experiment. In addition, five untreated crabs were used as the untreated control group in the microorganism challenge. Hepatopancreas organs were collected from untreated control and microorganism-challenged treatment groups (LPS, PGN, S. aureus, and V. parahaemolyticus). All these tissue samples were stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction.

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from the tissues according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Spin-column, BioTeke, Beijing, China). First-strand cDNA was obtained using PrimeScript First-strand cDNA synthesis kit with Oligo dT Primer from Takara (Dalian, China). The cDNA mixture was diluted 10 times with PCR-grade water and then stored at −80 °C for qRT-PCR analysis.

Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA expression

The mRNA expression levels of EsCnx and EsCrt in different tissues and their temporal expression in the hepatopancreas of crabs after the treatments were measured by SYBR Green fluorescent RT-PCR. Two pairs of specific primers (EsCnx-RT-F and EsCnx-RT-R, as well as EsCrt-RT-F and EsCrt-RT-R) were used to amplify the corresponding products of EsCnx and EsCrt. The PCR products were sequenced to verify the specificity of qRT-PCR. Two glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primers, namely, EsGAPDH-RT-F and EsGAPDH-RT-R (Table 1), were used for amplifying the 268-bp fragment as an internal control to verify successful transcription and to calibrate the cDNA template for corresponding samples. All samples were analyzed in triplicate in the qRT-PCR analysis. The expression levels of EsCnx and EsCrt were analyzed using the comparative CT method54; the discrepancy between the CT for EsCnx or EsCrt, and GAPDH (ΔCT) was calculated to normalize the variation in the amount of cDNA in each reaction. Moreover, EsCnx and EsCrt expression levels were calculated by 2−ΔΔCT. The obtained data were statistically analyzed using an unpaired sample t-test. Significant difference was accepted as P < 0.05.

Recombinant expression and purification of EsCnx and EsCrt in E. coli

The cDNA fragments encoding the Crt domains of EsCnx and EsCrt were amplified using the following primers: EsCnx-ex-F and EsCnx-ex-R, as well as EsCrt-ex-F and EsCrt-ex-R (Table 1), with EcoR I and Not I sites. The amplified products were cloned into pGEX-4T-1 vector (Novagen) and then transformed into competent E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells (TransGen Biotech). The positive clones were screened through PCR reaction using specific primers and then confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. The cells were grown at 37 °C in LB medium under agitation until an OD600 of 0.6–0.8. Recombinant expression was induced by addition of isopropyl-b-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.5 mmol L−1). The samples were then incubated for another 4 h under the same conditions. rEsCnx and rEsCrt were examined by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). In addition, rEsCnx and rEsCrt with a glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag and GST protein was purified using glutathione Sepharose 4B chromatography (Gen-Script, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis of localization and expression profiles of EsCnx and EsCrt proteins

Antisera for EsCnx and EsCrt were provided by Dr. Xian-Wei Wang (Shandong University)39,55. The heart, hepatopancreas, gills, muscle, intestine, nerve, and eyestalk of healthy crabs were homogenized in a buffer solution (50 mM Tris–HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF). The solution was then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to collect the supernatant. The hemolymph of normal or challenged crabs was prepared for analysis. The protein concentration was determined using the method described by Bradford. For Western blot analysis, each sample (100 μg protein) separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel was transferred onto a pre-wetted nitrocellulose membrane in electro blotting buffer under a constant current of 80 V for 100 min. The membrane was blocked in 5% non-fat dried milk in TBS (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) at room temperature for 2 h. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with 1/1000 diluted antiserum to EsCnx or EsCrt in TBS at 4 °C overnight and washed three times with TBST (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20) for 10 min. The membranes were then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1/5000 diluted in TBS) at room temperature for 2 h and then washed three times with TBST for 10 min. Protein bands were stained with 3,3-diaminobenzidine for 10 min, and the reaction was terminated by washing with distilled water.

Immunofluorescence

Healthy crab was swabbed with 75% ethanol, and hemolymph was collected with an equal volume of ACD-B53. The diluted hemolymph was centrifuged at 300 × g at 4 °C for 10 min to collect the cells, which were washed two times in culture medium. The cells were resuspended gently in 2 mL culture medium, and 0.2 mL aliquots were seeded into 2 mL of culture medium on 12-well dishes with glass coverslips and then incubated at 28 °C. After attachment to the coverslips, the cells were washed three times with PBS. Paraformaldehyde solution (4%) in PBS was used to fix the cells for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed in PBS three times and treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 solution for 10 min. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were treated with 5% BSA, blocked for 2 h, and then incubated with 1/1000 diluted rabbit antiserum to EsCnx or EsCrt in PBS at 4 °C overnight. The cells were washed four times with PBST and then incubated with Andy FluorTM 594 Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Antibodies (Beyotime, China) for 1 h. After washing four times with PBST, the cells were incubated with 500 μL of 25 μM DiOC6(3) (Beyotime, China) diluted in PBS at 37 °C for 10 min. The plates were washed as described above, and the cells were mounted on glass slides containing ProLong gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). After final washing, the cells were incubated in PBS and observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope.

Microbial binding assay

The binding assay was performed as described earlier56. Briefly, microorganisms were collected and resuspended in TBS to OD600 of 1.0 and then incubated with recombinant EsCnx and EsCrt (600 μg/mL, 50 μL) for 30 min with gentle rotation at room temperature. The microorganisms were pelleted, washed four times with TBS, and then loaded onto 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel. The bound protein was detected by Western blot analysis using anti-GST antiserum. For the control, bacterial cells were incubated with rArf (600 μg/mL) and GST-tagged proteins and then subjected to the same treatments.

Direct binding to PAMPs

ELISA assay was performed to detect the direct binding of EsCnx and EsCrt to LPS and PGN, as described previously56. LPS (50 μL) or PGN (80 μg/mL) was used to coat a 96-well microtiter plate. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C overnight, heated at 60 °C for 30 min, and then blocked with 200 μL/well BSA (600 μg/mL) in TBS for 2 h at 37 °C. After washing four times with TBS (200 μL/well), the purified EsCnx, EsCrt, or GST (control) was diluted in TBS containing 0.1 mg/mL BSA to achieve different concentrations (0–50 μg/mL) and added to each well (50 μL/well). Subsequently, the wells were incubated for 3 h at room temperature. The plates were then washed as described above, and anti-GST antiserum (1/2000 dilution) was added to the wells (100 μL/well). After 1 h of incubation at 37 °C, the wells were washed as described above. Approximately 100 μL of peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1/5000 dilution) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After final washing, color was enhanced by adding 0.01% 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma) liquid substrate in citric acid–Na2HPO4 buffer. The reaction was terminated by adding 2 M H2SO4, and the absorbance was read at 450 nm. The binding assay was performed three times.

V. parahaemolyticus clearance assay

Overnight-cultured V. parahaemolyticus was washed and resuspended in PBS. V. parahaemolyticus (approximately 3 × 107 cells) was incubated with rEsCnx or rEsCrt (600 μg/mL, 500 μL) at 28 °C for 30 min with rotation. In addition, V. parahaemolyticus was incubated with GST (600 μg/mL, 500 μL) as a control. Two groups of mixtures (50 μL each) were injected into the crabs. The hemolymph (500 μL) of three crabs was collected at different post injection times (2, 10, and 15 min). After serial dilution with PBS, the samples (30 μL) were plated onto LB broth plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C, and the number of bacterial clones in the plate was counted thereafter. Subsequently, the percentage of residual bacteria (i.e., (number of bacteria in plasma at 10 or 15 min/number of bacteria in plasma 2 min after injection) × 100) was determined.

V. parahaemolyticus clearance assay after siRNA interference

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), specifically those targeting EsCnx or EsCrt, were synthesized using an In vitro Transcription T7 Kit (Takara, Japan). EsCnx-siRNA and EsCrt-siRNA were used, and the siRNA sequence was scrambled to generate the control EsCnx-siRNA-scrambled or EsCrt-siRNA-scrambled (Table 1). Approximately 20 μg of siRNA (or siRNA-scrambled) was injected into the foot of the third appendage at a volume of 50 μL per crab. At 12 h after injection, the siRNA or siRNA-scrambled (20 μg) was injected into the same crab. At 24 h after the last injection, the total RNA of hemocytes from the two groups of crabs was isolated and used to detect the efficiency of RNAi through qRT-PCR. The remaining crabs were used for the clearance assay using the method described above with some modifications. In the modified clearance assay, 25 μL of V. parahaemolyticus (approximately 3 × 107 cells), which was not incubated with the recombinant protein, was injected into the crab. The assays described earlier were biologically repeated three times.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Huang, Y. et al. Two endoplasmic reticulum proteins (calnexin and calreticulin) are involved in innate immunity in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Sci. Rep. 6, 27578; doi: 10.1038/srep27578 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The current study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31572647), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20131401), Natural Science Fund of Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province (14KJA240002), Graduate students Research and Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYZZ15_0214), and the Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.H., Q.R., K.M.H., M.J., S.W.Y. and W.W. carried out the experiments. Y.H. and Q.R. designed the experiments and analysed the data. Y.H. and Q.R. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

References

- Fink A. L. Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol Rev 79, 425–449 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J. Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Biochem 70, 603–647 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. C., Agashe V. R., Siegers K. & Hartl F. U. Pathways of chaperonemediated protein folding in the cytosol. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5, 781–791 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. B. Beyond lectins: the calnexin/calreticulin chaperone system of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci 119, 615–623 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Karnovsky A., Sans M. D., Andrews P. C. & Williams J. A. Molecular characterization of the endoplasmic reticulum: insights from proteomic studies. Proteomics 10, 4040–4052 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe H. & Michalak M. ERp57, a multifunctional endoplasmic reticulum resident oxidoreductase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42, 796–799 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari M. & Helenius A. Chaperone selection during glycoprotein translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum, Science 288, 331–333 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodan A. R., Simons J. F., Trombetta E. S. & Helenius A. N-linked oligosaccharides are necessary and sufficient for association of glycosylated forms of bovine RNase with calnexin and calreticulin. Embo J 15, 6921–6930 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapun A., Jakob C. A., Thomas D. Y. & Bergeron J. J. Protein folding in a specialized compartment: the endoplasmic reticulum. Structure 7, R173–182 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond C., Braakman I. & Helenius A. Role of N-linked oligosaccharide recognition, glucose trimming, and calnexin in glycoprotein folding and quality control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91, 913–917 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P. S. & Arvan P. Calnexin and BiP act as sequential molecular chaperones during thyroglobulin folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 128(1/2), 29–38 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degen E. & Williams D. B. Participation of a novel 88-kD protein in the biogenesis of murine class I histocompatibility molecules. J Cell Biol 112, 1099–1115 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada I. et al. SSR alpha and associated calnexin are major calcium binding proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J Biol Chem 266, 19599–19610 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstenbach F., David V., Watkins S. & Brenner M. B. Endoplasmic reticulum resident protein of 90 kilodaltons associates with the T- and B-cell antigen receptors and major histocompatibility complex antigens during their assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89, 4734–4738 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin K. et al. The major histocompatibility complex class I antigen-binding protein p88 is the product of the calnexin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89, 8452–8456 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron J. J., Brenner M. B., Thomas D. Y. & Williams D. B. Calnexin: a membrane-bound chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Trends Biochem Sci 19, 124–128 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Franklin A. E. & Hoffman N. E. Primary structure and characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana calnexin-like protein. J Biol Chem 268, 6560–6566 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L. & Frickel E. M. Calnexin, calreticulin, and ERp57: teammates in glycoprotein folding. Cell Biochem Biophys 39, 223–247 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkevich L. A. & Williams D. B. Participation of lectin chaperones and thiol oxidoreductases in protein folding within the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr Opin Cell Biol 23, 157–166 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderick H. L., Lechleiter J. D. & Camacho P. Cytosolic phosphorylation of calnexin controls intracellular Ca2+ oscillations via an interaction with SERCA2b. J Cell Biol 149, 1235–1248 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Taubenberger A. et al. Calreticulin and calnexin in the endoplasmic reticulum are important for phagocytosis. Embo J 20, 6772–6782 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delom F., Fessart D. & Chevet E. Regulation of calnexin sub-cellular localization modulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Apoptosis 12, 293–305 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelebart P., Opas M. & Michalak M. Calreticulin, a Ca2+-binding chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37, 260–266 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak M., Groenendyk J., Szabo E., Gold L. I. & Opas M. Calreticulin, a multiprocess calcium-buffering chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J 417, 651–666 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núnez M. T., Osorio A., Tapia V., Vergara A. & Mura C. V. Iron-induced oxidative stress up-regulates calreticulin levels in intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells. J Cell Biochem 82(4), 660–665 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto J. P. et al. Protective role of calreticulin in HFE hemochromatosis. Free Radic Biol Med 44(1), 99–108 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L. et al. Novel anti-oxidative role of calreticulin in protecting A549 human type II alveolar epithelial cells against hypoxic injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294(1), C47–55 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opas M., Dziak E., Fliegel L. & Michalak M. Regulation of expression and intracellular distribution of calreticulin, a major calcium binding protein of nonmuscle cells. J Cell Physiol 149, 160–171 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer R. D., Lieu T. S. & Capra J. D. The diverse functional repertoire of a new human autoantigen. Immunology 1, 155–160 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald T. J. & MacLennan D. H. Isolation of a high affinity calcium binding protein from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 249, 974–979 (1974). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak M., Corbett E. F., Mesaeli N., Nakamura K. & Opas M. Calreticulin: one protein, one gene, many functions. Biochem J 344, 281–292 (1999). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luana W. et al. Molecular characteristics and expression analysis of calreticulin in Chinese shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 147, 482–491 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. et al. Molecular responses of calreticulin genes to iron overload and bacterial challenge in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Dev Comp Immunol 35, 267–272 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. et al. Molecular cloning and functional study of calreticulin from a lepidopteran pest, Pieris rapae. Dev Comp Immunol 38, 55–65 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visudtiphole V., Watthanasurorot A., Klinbunga S., Menasveta M. & Kirtikara K. Molecular characterization of calreticulin: a biomarker for temperature stress responses of the giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon. Aquaculture 308, S100–108 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S., Michalak M., Opas M. & Eggleton P. The ins and outs of calreticulin: from the ER lumen to the extracellular space. Trends Cell Biol 11, 122–129 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watthanasurorot A., Jiravanichpaisal P., Soderhall K. & Soderhall I. A calreticulin/gC1qR complex prevents cells from dying: a conserved mechanism from arthropods to humans. J Mol Cell Biol 5(2), 120–131 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y. F. et al. Molecular responses of calreticulin gene to Vibrio anguillarum and WSSV challenge in the ridgetail white prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda. Fish Shellfish Immunol 36, 164–171 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. et al. Calnexin functions in antibacterial immunity of Marsupenaeus japonicas. Dev Comp Immunol 46, 356–363 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. W. & Wang J. X. Diversity and multiple functions of lectins in shrimp immunity. Dev Comp Immunol 39(1–2), 27–38 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen R., Li F. H., Sun Z., Li S. H. & Xiang J. H. Shrimp MyD88 responsive to bacteria and white spot syndrome virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol 34, 574–581 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross P. S., Bartlett T. C., Browdy C. L., Chapman R. W. & Warr G. W. Immune gene discovery by expressed sequence tag analysis of haemocytes and hepatopancreas in the Pacific White Shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, and the Atlantic White Shrimp, L. setiferus. Dev Comp Immunol 25, 565–577 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. & Granados R. R. Calcofluor disrupts the midgut defense system in insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 30(2), 135–143 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet-Gely I., Lemaitre B. & Boccard F. Bacterial strategies to overcome insect defences. Nat Rev Microbiol 6(4), 302–313 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. et al. Function of two novel single-CRD containing C-type lectins in innate immunity from Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol 37, 313–321 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway C. A. & Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol 20, 197–216 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. & Janeway C. A. Jr. Decoding the patterns of self and nonself by the innate immune system. Science 296, 298–300 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. S., Shu M. A., Zhan X. A. & Wang S. X. Identification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from cultured Eriocheir sinensis and pathogenicity of its extracellular products. J Fish China 26, 357–362 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie J. P., Kanost M. R. & Trenczek T. Biological mediators of insect immunity. Annu Rev Entomol 42, 611–643 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiravanichpaisal P., Lee B. L. & Soderhall K. Cell-mediated immunity in arthropods: hematopoiesis, coagulation, melanization and opsonization. Immunobiology 211, 213–236 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannagan R. S., Jaumouille V. & Grinstein S. The cell biology of phagocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol 7, 61–98. (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Nei M., Dudley J. & Tamura K. MEGA: a biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief Bioinform 9, 299–9306 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. et al. Cloning and characterization of a clip domain serine protease and its homolog (Masquerade) from Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol 35, 1155–1162 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(–ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. W., Xu H., Xu J. D., Zhao X. F. & Wang J. X. Collaboration between a soluble C-Type lectin and Calreticulin facilitates White Spot Syndrome Virus infection in Shrimp. J Immunol 193, 2106–2117 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. et al. A novel integrin function in innate immunity from Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Dev Comp Immunol 52, 155–165 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.