Abstract

Rare in the general public, dural ectasia is a common finding in patients with Marfan syndrome. Complications are not frequent but include constipation, urinary retention, and meningitis. Presented here is a case of bacterial meningitis secondary to fistulous communication between a sacral meningocele and sigmoid colon in the setting of diverticulitis.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography

Introduction

Dural ectasia is a well-described feature of the Marfan syndrome, previously one of the major criteria in the Ghent nosology (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). In the recently revised Ghent nosology, dural ectasia is given a systemic score of 2 out of 3. A sensitive but nonspecific sign of the Marfan syndrome, dural ectasia also occurs in patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome and the vascular form of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (6). In Marfan syndrome, it is the second most common manifestation after cardiovascular problems and is seen in up to two-thirds of patients (7, 8). Although the condition can be associated with back pain, some patients are asymptomatic. The severity of dural ectasia increases with age (4).

In some patients, dural ectasia may progress to an anterior meningocele. Sequelae include constipation, urinary retention, and meningitis. Reported here is a unique complication of anterior sacral meningocele.

Case report

A 45-year-old woman diagnosed with Marfan syndrome as a child was admitted to an outside hospital for a presumed ovarian cyst removal. At surgery, the cystic mass was discovered to actually represent an anterior sacral meningocele (Fig. 1), which was inadvertently punctured. The patient recovered without significant complication. Owing to the lack of symptomatology from the meningocele, surgery was deemed not to be indicated.

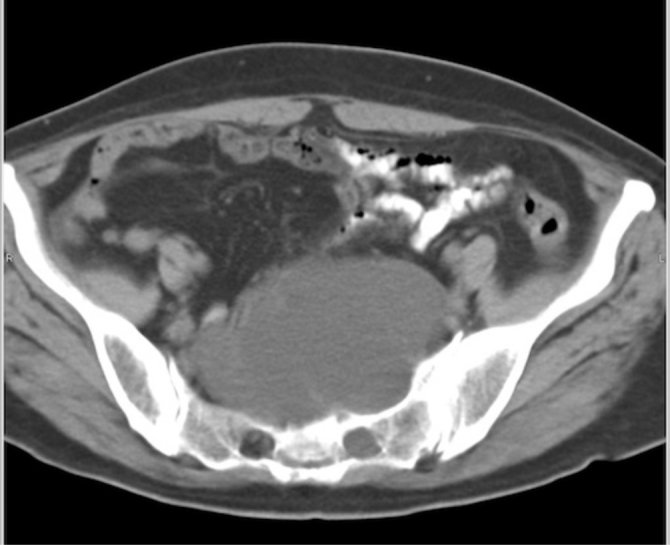

Figure 1.

45-year-old woman with Marfan syndrome. Axial, contrast-enhanced image of the pelvis shows a large presacral cyst. Continguity with the sacrum, widening of the neural foramen, dural ectasia involving other nerve root sleeves (not shown), and clinical history enable the appropriate diagnosis of left S1 anterior sacral meningocele.

Five years later, the patient developed acute symptoms of low back pain, stiff neck, and headache, and was diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. Intraventricular pneumocephalus was seen on head CT. CT of the abdomen/pelvis revealed the cause: sigmoid diverticulitis complicated by a fistulous tract to the sacral meningocele (Fig. 2).

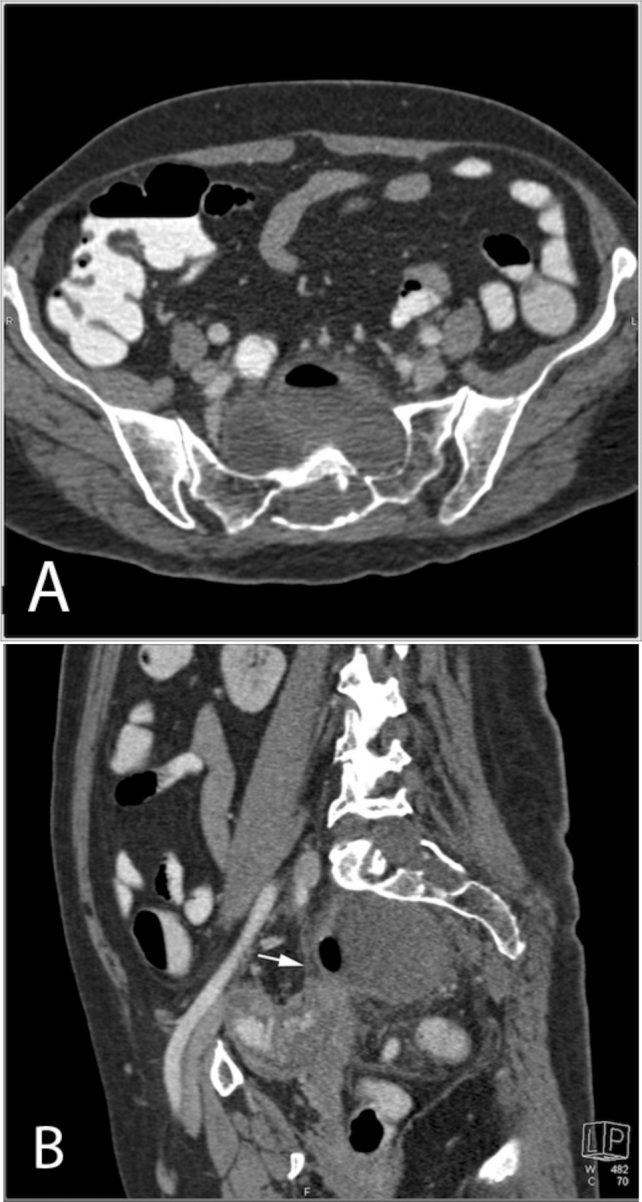

Figure 2.

Same patient (45-year-old woman with Marfan syndrome) as in Fig. 1, five years after original CT. A: Axial IV contrast-enhanced image of the pelvis shows decrease in size of the presacral cyst with a new air-fluid level. B: Sagittal oblique MPR from IV contrast-enhanced image of the pelvis demonstrates secondary findings of fistula formation, including wall thickening and pericolonic inflammation of the sigmoid colon, absence of a fat plane between the sigmoid and the meningocele, and air within the meningocele.

The patient underwent sigmoidectomy and colostomy formation. Using a posterior approach, the neurosurgery team resected the fistula and partially removed the large anterior meningocele. Three weeks postoperatively, she was discharged in good condition.

Discussion

Dural ectasia is defined as enlargement of the dural sac, typically in the lumbosacral region and particularly at L3 and S1. Associated findings include thinning of pedicles and laminae, widening of the neural foraminae, or anterior sacral meningocele (1, 2, 3, 5). Increased cerebrospinal fluid hydrostatic pressure in the lower spine is thought to gradually cause stretching of the dural sac and remodeling of the bony spinal canal. This can result in neural, foraminal, dural outpouchings and anterior meningoceles (1, 7, 8).

In addition to being associated with Marfan syndrome, dural ectasia may also be associated with neurofibromatosis and other connective-tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (3). The Currarino triad includes congenital anorectal stenosis, sacral bone defect, and presacral mass, originally described as a meningocele, teratoma, or enteric cyst (9).

The most common symptom associated with dural ectasia is back pain. Neurologic deficits are rare; headache, radiculopathy, and abdominal pain have been described (8). Anterior sacral meningoceles have been reported to enlarge with age, and complications can be related to mass effect, including constipation, urinary retention, and prolonged labor in women. A sacral meningocele can also predispose the patient to recurrent episodes of meningitis (10).

Although very rare, fistulous communication of an anterior meningocele with adjacent bowel has been reported, usually resulting in bacterial meningitis (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18). Three case reports describe fistulous communication in patients with rectal cancer treated with surgery and radiation (12, 13, 18). A few reports have described meningitis resulting from intervention (for example) after aspiration of a presumed cyst, or following trauma (15, 16).

To the best of our knowledge, our case is the first to describe diverticulitis complicated by fistulous communication to an anterior sacral meningocele in the setting of Marfan syndrome. Fistula formation complicating diverticulitis is most frequently colovesical, with colovaginal and colocutaneous formation being much less common (19). In a retrospective review of 192 patients with colonic diverticulitis performed by Bahadursingh et al, 4.6% had fistulas. Of those with fistulas, 44% were colovesicular, 22% colocutaneous, 22% enterocolic, and 11% colovaginal (20).

Anterior sacral meningoceles are unfortunately occasionally confused with ovarian cysts or other pelvic cystic masses. Misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary and potentially harmful surgical procedures. Puncture of the meningocele may result in a cerebrospinal fluid leak, fistula, or meningitis.

Treatment of an anterior sacral meningocele is controversial. Some authors strongly recommend surgical treatment of meningoceles due to their potential risk for complication (10, 11). Regardless, CT is an excellent imaging tool to define the connection between colon and meningocele and determine the underlying etiology, which in this case was acute diverticulitis.

Footnotes

Published: February 18, 2012

References

- 1.De Paepe A, Devereux RB, Dietz HC. Revised diagnostic criteria for the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1996;62:417–426. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960424)62:4<417::AID-AJMG15>3.0.CO;2-R. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishman EK, Zinreich SJ, Kumar AJ. Sacral abnormalities in Marfan syndrome. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1983;7:851–856. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198310000-00019. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pyeritz RE, Fishman EK, Bernhardt BA. Dural ectasia is a common feature of the Marfan syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;43:726–732. [PubMed] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fattori R, Nienaber CA, Descovich B. Importance of dural ectasia in phenotypic assessment of Marfan’s syndrome. Lancet. 1999;354:910–913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)12448-0. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oosterhof T, Groenink M, Hulsmans FJ. Quantitative assessment of dural ectasia as a marker for Marfan syndrome. Radiology. 2001;220:514–518. doi: 10.1148/radiology.220.2.r01au08514. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loeys BL, Dietz HC, Braverman AC. The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010 Jul;47(7):476–485. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.072785. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones KB, Sponseller PD, Erkula G. Symposium on the musculoskeletal aspects of Marfan syndrome: meeting report and state of the science. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:413–422. doi: 10.1002/jor.20314. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn NU, Sponseller PD, Ahn UM. Dural ectasia is associated with back pain in Marfan syndrome. Spine. 2000;25:1562–1568. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006150-00017. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Currarino G, Coln D, Votteler T. Triad of anorectal, sacral, and presacral anomalies. Am J Radiol. 1981;137:395–398. doi: 10.2214/ajr.137.2.395. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips JT, Brown SR, Mitchell P. Anaerobic meningitis secondary to a rectothecal fistula arising from an anterior sacral meningocele: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1633–1635. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0646-7. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner PA, Albright AL. “Like mother, like son:” hereditary anterior sacral meningocele: case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2006;104(2 Suppl Pediatrics):138–142. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.104.2.11. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh TJ, Weinstein RA, Malinoff H. Meningorectal fistula as a cause of polymicrobial anaerobic meningitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982;78:127–130. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/78.1.127. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chun C, Sacks B, Jao J. Polymicrobial feculent meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:693–694. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.3.693. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick MO, Taylor WA. Anterior sacral meningocele associated with a rectal fistula. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(1 Suppl):124–127. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.91.1.0124. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blond MH, Borderon JC, Despert F. Anterior sacral meningocele associated with meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:783–784. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerin JM, Leibinger F, Raskine L. Polymicrobial meningitis revealing an anterior sacral meningocele in a 23-year-old woman. J Infect. 2000;40:195–197. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(00)80019-5. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez AA, Iglesias CD, Lopez CD. Rectothecal fistula secondary to an anterior sacral meningocele. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:487–489. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/8/5/487. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Lechuz JM, Hernangómez S, San Juan R, Bouza E. Feculent meningitis: polymicrobial meningitis in colorectal surgery. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;38:169–170. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(00)00184-x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferzoco LB, Raptopoulos V, Silen W. Acute diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1521–1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382107. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahadursingh AM, Virgo KS, Kaminski DL. Spectrum of disease and outcome of complicated diverticular disease. Am J Surg. 2003;186:696–701. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.08.019. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]