Abstract

In pediatric oncology, positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) is emerging as an essential diagnostic tool in characterizing suspicious neoplastic lesions and staging malignant diseases. Most studies regarding the possible role of FDG-PET/CT in the management of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients are limited to adults. Here we report a pediatric patient with recurrent ALL, in which FDG-PET/CT was used both to define more precisely the cause of lymphadenopathy and to assess the effect of the second-line therapy.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; CT, computed tomography; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most frequent malignant neoplasm in childhood and accounts for approximately 30% of pediatric cancers (1). Although cytotoxic drug protocols have led to a remarkable improvement in the prognosis of this disease, a subset of children with ALL still relapse.

The clinical suspicion of recurrence may at times be difficult to define, since many other conditions (such as infection and drugs) induce similar symptoms including cytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphoadenopathy.

Positron emission tomography (PET) with 2-18F-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) has been reported as being a reliable, noninvasive, diagnostic imaging tool for various kinds of malignancies, including lung cancers (2), colorectal cancer (3), head and neck epithelial neoplasia (4), thyroid carcinoma (5), and breast cancer (6). This technique is also useful in detecting extramedullary neoplastic infiltrates in an acute myeloid leukemia patient (7). As regards the role of FDG-PET in lymphoid malignancies, many studies have been carried out on both Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patients (8, 9). However, data concerning lymphoid leukemia are, at present, limited to reports describing the detection of ALL involvement of tissues other than lymph nodes in adult patients (10, 11, 12). FDG-PET is also emerging in pediatric oncology as both an integral part of the staging process and an essential tool in assessing therapy response (13, 14).

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) is a hybrid diagnostic technique that allows a combination of both anatomical and biological coregistered images to be acquired in the same session. The CT scan increases PET topographic accuracy in the detection of neoplastic lesions.

We report a case of an ALL off-therapy patient, in which FDG-PET/CT was used to define more clearly the cause of lymphadenopathy. A subsequent histopathological exam revealed that this lymphadenopathy was due to disease recurrence. FDG-PET/CT was then used to assess the effect of the second-line therapy.

Case report

A 4-year-old boy was diagnosed with pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). He was enrolled and treated according to the AIEOP (Italian Association of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology)-BFM (Berlin-Frankfurt-Munich) ALL 2000 Study Protocol (protocol for the diagnosis and treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in pediatric patients). He was diagnosed disease-free and was off-therapy two years later.

Five years later, the patient was re-evaluated for isolated submandibular lymphadenopathy. The physical exam showed generally good physical condition, with no fever, a slight (1/6) heart murmur, no respiratory abnormalities, and no hepatosplenomegaly. In the left submandibular region was a distinct mobile, hard, painful mass measuring 2 cm in diameter, with no signs of inflammation in the overlying skin. The pharynx and oral cavity were normal. The peripheral blood smear and hematologic indices were normal, as were hepatic and renal function. Furthermore, there was no serological evidence of a recent infection (Toxoplasma, Bartonella, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus were IgG-negative). A tuberculin skin test was negative. Empirical antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapy with claritromycin and ketoprofene was given without any results.

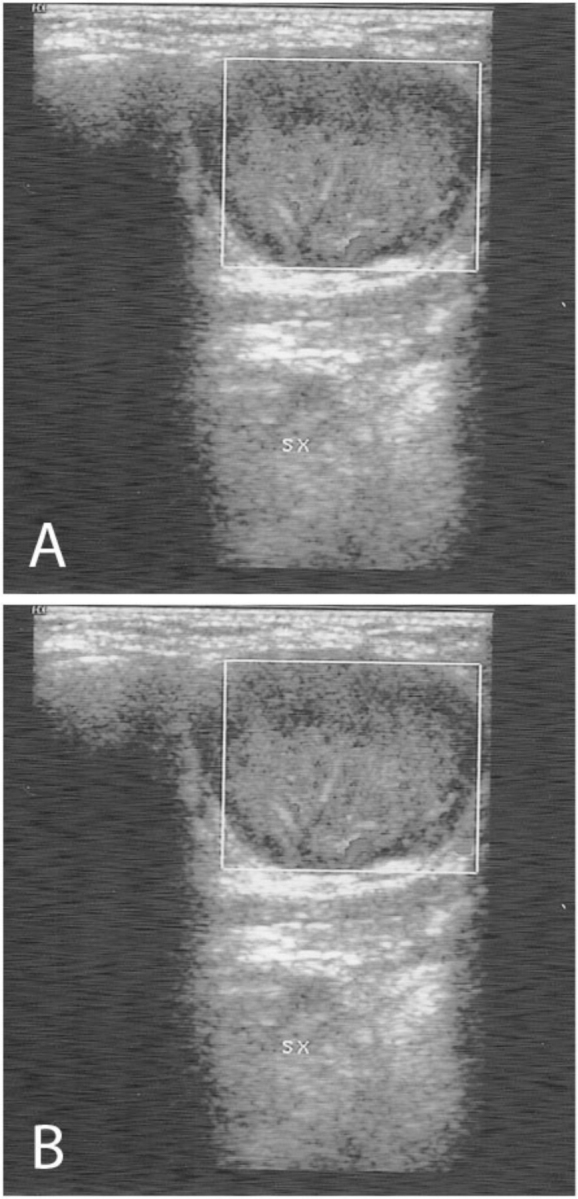

One week later, ultrasonography (US) of the neck highlighted the presence of a hypoechoic lymph node in the left submandibular region measuring 2.34 cm × 1.89 cm. This node had an heterogeneous appearance, with well-confined edges and demonstrated early signs of internal liquefactive necrosis. The right lateral cervical lymph nodes were normal in shape and size. The left-sided nodes appeared enlarged but displayed normal US features. The antibiotic therapy was changed to rifampicin. After one week, no notable changes could be seen by US. A chest radiograph and an abdominal US performed at this time were both normal.

Even though the US images showed no suspicion for a recurrence of the primary disease, the poor response to antibiotic therapy and the absence of other causes of the lymphadenopathy led to a total body FDG-PET/CT study in order to metabolically characterize the lymph nodes. This study was performed using a Discovery-STE PET/CT system (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI), 60 minutes after intravenous injection of 18F-FDG (167 MBq). At the time of the tracer injection, the patient had fasted for over six hours, and his glucose blood level was 94 mg/dl. The data was acquired in 3D mode, with attenuation correction calculated by coregistered CT images.

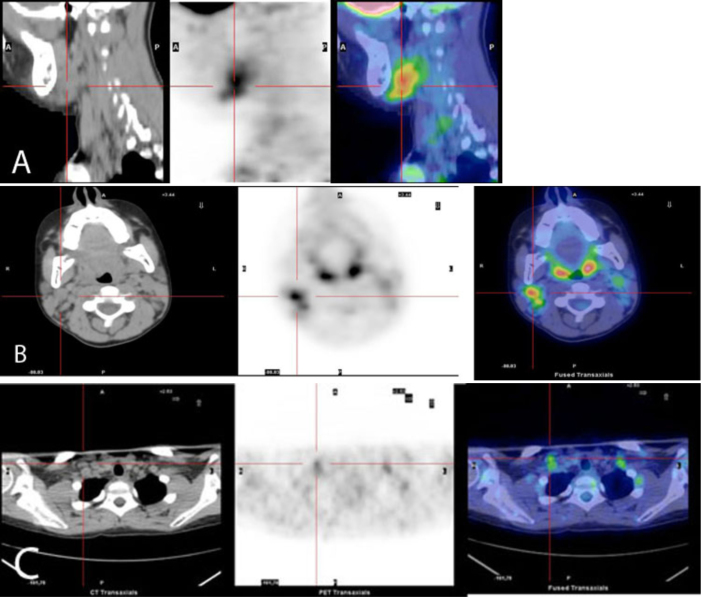

The PET study showed the presence of heterogeneous uptake on the bilateral lateral cervical and bilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes, suggesting the presence of disease with high metabolic activity in these sites (Fig. 1). A complete left submandibular lymph-node excision and a bone-marrow aspiration were done. The histopathological exam revealed a total alteration of the normal structure of the lymph node, with a massive neoplastic invasion by small lymphoid blasts. Immunophenotypic analysis showed that these cells were positive for CD10, CD19, TdT, and CD38. The bone-marrow aspiration showed the presence of 5% pre-B blasts.

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography of the neck shows (A) the presence of a hypoechoic lymph node with a heterogeneous appearance in the left submandibular region, with well-confined edges and early signs of internal liquefactive necrosis, and B) right lateral cervical lymph nodes that are normal in shape and size.

In light of data from the lymph node biopsy, bone-marrow aspirate, and PET-CT scan, the patient was diagnosis with a combined (bone marrow and multiple lymph nodes) recurrence of ALL. He was treated according to the AIEOP LLA REC2003 protocol (protocol to treat relapsing Philadelphia-chromosome-negative ALL).

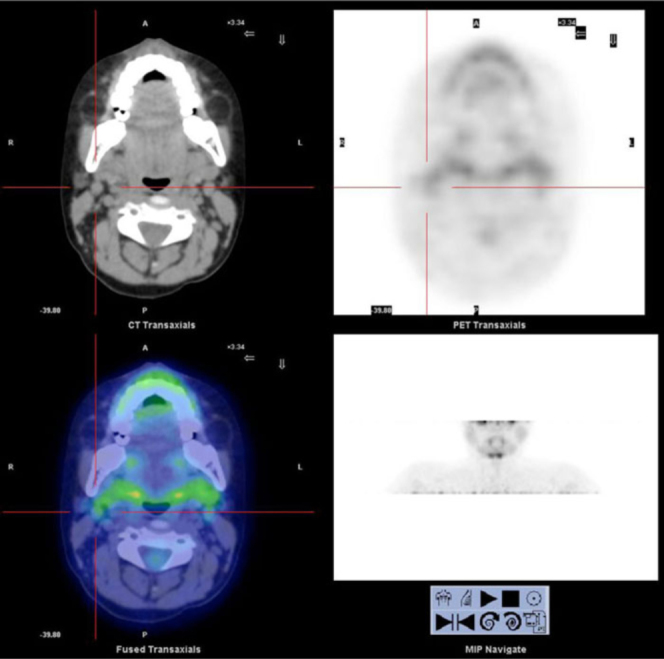

After completing second-line therapy, FDG PET/CT was repeated to restage the lymph-node disease. No pathological uptake was observed in the previously mentioned sites, suggesting a complete disease response to the treatment (Fig. 2). Moreover, the bone-marrow aspirate performed on the same day showed complete disease remission.

Figure 2.

Three adjacent, axial, T2-weighted MR images show retraction of the trapezius muscles from the spinous processes with surrounding hematoma. There are areas of nodularity within the fluid collection that represent torn fragments of muscle.

As an allogenic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) was indicated, a mismatched unrelated allograft was performed. One year following this transplant, the patient is alive, disease-free, and in good condition (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The post-treatment 18F-FDG PET/TC scan shows no pathologic uptake in the previously cited sites, suggesting complete response to therapy.

Discussion

Common sites of primary involvement or recurrence of ALL include the testicles (2%) (15) and the central nervous system (CNS) (5%-11%) (16). However, other organs such as ovaries, breast, eye, skin, and lymph nodes have also been reported as a possible target of the disease (17).

18F-FDG-PET is an advanced imaging tool for diagnosis, staging, and restaging of cancer, identifying the increased glycolytic activity in malignant cells. It is possible to image the entire body in a single session, increasing the opportunity of finding unsuspected disease sites (18).

The most remarkable suggestion arising from our case is the higher sensitivity of this imaging technique in the detection of ALL lymph-node involvement as compared to other techniques such as US. As regards our patient, the FDG-PET/CT scan correctly identified pathological uptake both in regions that were falsely negative for leukemic cell infiltrates on US (for example, right lateral cervical region) and those that are quite difficult to study due to their anatomical location, such as the supraclavicular region. Furthermore, while the US images of the enlarged lymph node suggested an infection, the FDG-PET/CT scan raised a suspicion for recurrence that was later confirmed by the histopathological exam. This suggests that FDG-PET/CT also provides a better specificity than US.

However, FDG is not a cancer-specific agent, and false-positive findings have been reported. Infectious diseases (mycobacterial, fungal, and bacterial), sarcoidosis, radiation pneumonitis, and postoperative surgical conditions are associated with intense uptake of FDG on PET scans (19).

On the other hand, as reported in literature, limited sensitivity related to the size of metastatic deposits can be a particular problem with FDG-PET (20). Yet it has also been suggested that the detection of subclinically metastatic nodes in FDG-PET depends not only on the nodal size but also (to a greater degree) on the intranodal tumor burden (21).

Nevertheless, our case suggests some promising features of FDG-PET/CT scan in ALL, such as the opportunity to further guide diagnostic interventions and thus focus on probable sites of disease recurrence. FDG-PET/CT also has the advantage of staging tissues other than blood with just a single exam. Endo et al. reported a rare case of an adult patient with ALL who suffered a relapse in the bone marrow of the extremities following allogeneic peripheral blood-stem-cell transplantation (22). These authors suggested that in cases of disease recurrence in unusual sites, evaluation by MRI and FDG-PET may be of value in detecting these relapses (22). Moreover, whole-body FDG-PET/CT during the course of the therapy might be useful in assessing the chemotherapeutic effects on identified lesions. This type of effect is accepted as one of the most important prognostic factors in ALL (23, 24).

The findings in our patient are consistent with those from previous reports. However, our case demonstrated some original features, such as the opportunity to intentionally detect leukemic cell infiltrates in lymph nodes, and the application of FDG-PET/CT in pediatric ALL patients.

However, the limits of this diagnostic tool must be also considered. The main limits of FDG-PET/CT scan are the exposure of the patient to an estimated radiation dose of approximately 25 mSv (25), which can be a significant problem in pediatric patients (26, 27). The present availability and costs of the FDG-PET/CT are other limitations. It is clearly evident that more studies are needed to assess a possible role of FDG-PET/CT in the management of ALL patients. If the suggestions arising from this report are confirmed, FDG-PET/CT may be included in future clinical practice for disease staging, evaluating the response to the chemotherapy in identified lesions and in the restaging for recurrence of extramedullary disease.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Mr. Glenn John Richardson and Mr. Adriano Del Testa for editorial assistance and Mr. Andrew Martin Garvey for patiently reviewing our paper.

Footnotes

Published: October 31, 2011

References

- 1.Ries LA, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973-1996. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, Md: 1999. On-line edition. Last accessed October 19, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dewan NA, Reeb SD, Gupta NC, Scott WJ. PET-FDG imaging and transthoracic needle lung aspiration biopsy in evaluation of pulmonary lesions. A comparative risk-benefit analysis. Chest. 1995;108:441–446. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.2.441. [PubMed] ) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huebner RH, Park KC, Shepherd JE, Schwimmer J, Czernin J, Phelps ME, Gambhir SS. A meta-analysis of the literature for whole-body FDG PET detection of recurrent colorectal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1177–1189. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams S, Baum RP, Stuckensen T, Bitter K, Hör G. Prospective comparison of 18F-FDG PET with conventional imaging modalities (CT, MRI, US) in lymph node staging of head and neck cancer. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25:1255–1260. doi: 10.1007/s002590050293. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schluter B, Bohuslavizki KH, Beyer W, Plotkin M, Buchert R, Clausen M. Impact of FDG PET on patients with differentiated thyroid cancer who present with elevated thyroglobulin and negative 1311 scan. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:71–76. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avril N, Rose CA, Schelling M, Dose J, Kuhn W, Bense S. Breast imaging with positron emission tomography and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose: Use and limitations. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3495–3502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.20.3495. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuenzle K, Taverna C, Steinert HC. Detection of extramedullary infiltrates in acute myelogenous leukemia with whole-body positron emission tomography and 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose. Mol Imaging Biol. 2002;4:179–183. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(01)00056-5. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallamini A. Positron emission tomography scanning: a new paradigm for the management of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Haematologica. 2010;95(7):1046–1048. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.024885. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kostakoglu L, Leonard JP, Coleman M, Goldmith SJ. The role of FDG-PET imaging in the management of lymphoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2004;2:115–121. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ennishi D, Maeda Y, Niiya M, Shinagawa K, Tanimoto M. Incidental detection of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia on [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography. J Clin Oncol. 2009;36:269–270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7769. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis J, Smiley S, Battiwalla M, Wetzler M, Barcos M, Bshara W. Detection of extra-medullary relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia by radiographic imaging following allogenic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:827–828. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.183. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aregawi D, Sherman J, Douvas M, Burns TM, Schiff D. Neuroleukemiosis: case report of leukemic nerve infiltration in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38:1196–1200. doi: 10.1002/mus.21089. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy JJ, Tawfeeq M, Chang B, Nadel H. Early experience with PET/CT scan in the evaluation of pediatric abdominal neoplasms. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:2186–2192. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.08.064. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sironi S, Messa C, Cistaro A, Landoni C, Provenzi M, Giraldi E. Recurrent hepatoblastoma in orthotopic transplanted liver: detection with FDG positron emission t.omography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1214–1216. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.5.1821214. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hijiya N, Liu W, Sandlund JT, Jeha S, Razzouk BI, Ribeiro RC. Overt testicular disease at diagnosis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: lack of therapeutic role of local irradiation. Leukemia. 2005;19:1399–1403. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403843. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conter V, Aricò M, Valsecchi MG, Rizzari C, Testi AM, Messina C. Extended intrathecal methotrexate may replace cranial irradiation for prevention of CNS relapse in children with intermediate-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster-based intensive chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2497–2502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.10.2497. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chessells JM. Relapsed lymphoblastic leukaemia in children: a continuing challenge. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:423–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00776.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kostakoglu L, Agress H, Goldsmith S. Clinical role of FDG PET in evaluation of cancer patients. Radiographics. 2003;23:315–340. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025705. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang JM, Lee HJ, Goo JM, Lee HY, Lee JJ, Chung JK. False positive and false negative FDG-PET scans in various thoracic diseases. Korean J Radiol. 2006;7:57–69. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2006.7.1.57. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng SH, Yen TC, Chang JT, Chan SC, Ko SF, Wang HM. Prospective study of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma with palpably negative neck. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4371–4376. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7349. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pentenero M, Cistaro A, Brusa M, Ferrarsi MM, Pezzuto C, Carnino R. Accuracy of 18f-fdg-pet/ct for staging of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head & Neck. 2008;30(11):1488–1496. doi: 10.1002/hed.20906. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Endo T, Sato N, Koizumi K, Nishio M, Fujimoto K, Sakai T. Localized relapse in bone marrow of extremities after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:279–282. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20106. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pui C-H, Evans WE. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:166–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052603. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schrappe M, Reiter A, Riehm H. Cytoreduction and prognosis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2403–2406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.8.2403. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brix G, Lechel U, Glatting G, Ziegler SI, Münzing W, Müller SP, Beyer T. Radiation exposure of patients undergoing whole-body dual-modality 18F-FDG PET/CT examinations. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:608–613. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenner D, Elliston C, Hall E, Berdon W. Estimated risks of radiation induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:289–296. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760289. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donnelly L, Emery K, Brody A, Laor T, Gylys-Morin VM, Anton CG. Minimising radiation dose for pediatric body applications of single-detector helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:303–306. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760303. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]