Abstract

Background and purpose

Coronal and sagittal plane long bone deformities can be corrected with guided growth, whereas transverse plane rotational deformities require osteotomy and internal or external fixation. We investigated whether rotational changes can be introduced with the plating technique.

Methods

45 rabbits (6 weeks old) were divided into 3 groups. The unoperated right tibia was used as control. In groups 1 and 3, two plates were placed obliquely to the long axis and in different directions. In group 2, a sham operation was performed with screws. Animals in groups 1 and 2 were followed for 4 weeks. In group 3 the implants were removed 4 weeks after the operation to observe rebound effect, and the animals were followed for another 4 weeks. The tibial torsion was assessed on computed tomography (CT). External rotation was accepted as a negative value.

Results

In group 1, mean torsion was −20° (SD 7.9) in the right tibia and −2.9° (SD 7.2) in the left tibia (p < 0.001). In group 2, mean torsion was −23° (SD 4.9) in the right tibia and −26° (SD 6.5) in the left tibia (p = 0.2). In group 3, mean torsion was −21° (SD 6.3) in the right tibia and −9.5° (SD 5.3) in the left tibia (p < 0.001). Intergroup evaluation for left torsion showed a significant difference between group 2 and the other groups (p < 0.001). When the rebound effect was evaluated, there was no statistically significant difference between groups 1 and 3 (p = 0.08).

Interpretation

A rotational change was attained with this technique. Although a rebound effect was seen after implant removal, it did not reach statistical significance. The final rotational change remained constant.

In selected cases of intoeing gait in children, derotation osteotomies are performed (Cobeljić et al. 2006, Walton et al. 2012). Osteotomy has various disadvantages including over or undercorrection, recurrence of the deformity, difficulty in postoperative mobilization, and delayed recovery and return to daily life (Gyr et al. 2013, Stevens 2007). Other common deformities in growing children are angular deformities in the coronal/sagittal planes around the knee joint (Klatt and Stevens 2008, Palocaren et al. 2010, Stevens 2007). Surgical techniques used for the correction of angular deformities are osteotomy and acute correction, or distraction with external fixator (Yilmaz et al. 2014). These methods are technically challenging and they are associated with high complication rates, so less invasive methods are being investigated (Castañeda et al. 2006, Scott 2012). Permanent epiphysiodesis for the correction of deformity may cause overcorrection when growth is miscalculated (Schroerlucke et al. 2009). Temporary hemiepiphysiodesis/epiphysiodesis (guided growth) with low morbidity and low complication rates has become an important alternative to other techniques in growing children with angular deformities and leg-length discrepancy (Burghardt and Herzenberg 2010, Pendleton et al. 2013, Stevens 2007).

Guided growth, which is less invasive with few complications, has led to the idea that rotational deformities in the horizontal plane can be similarly corrected with rotationally guided growth rather than with the more invasive and complicated procedures such as osteotomy. The aim of this study was to alter the transverse plane rotational properties of the long bones in growth phase by placing 2 oblique plates opposite to each other, and to determine whether the resulting change would be permanent.

Methods

We used 45 New Zealand rabbits, 6 weeks old at the time of surgical intervention. The left lower extremity was operated and the unoperated right lower extremity was used as control. The animals were randomly assigned to 3 groups with 15 animals in each. In groups 1 and 3, operation was performed with plate and screws. In group 2, sham operations were performed with screws only. Animals in groups 1 and 2 were followed for 4 weeks. Animals in group 3 underwent implant removal 4 weeks after the index operation and they were followed for another 4 weeks to assess the rebound effect.

Anesthesia

The rabbits were premedicated with intramuscular (i.m.) xylazine (5 mg/kg). Induction was carried out with i.m. ketamine (30 mg/kg). After induction, they were intubated and inhalation anesthesia was given with isoflurane (4% concentration initially, and 2% during maintenance).

Surgery

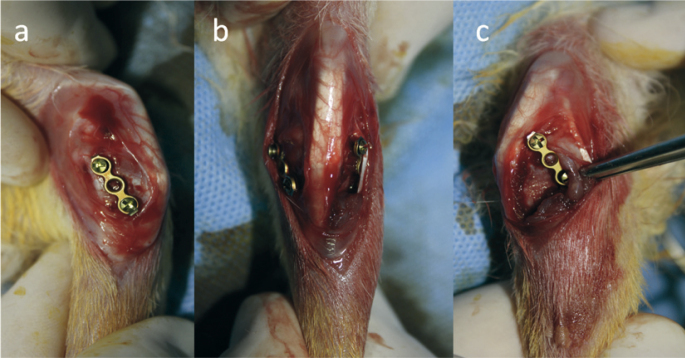

The principle of the method is based on creation of a rotation in the physeal line by placing 2 oblique plates onto the medial and lateral aspects of the physis, without interfering with bone growth. The surgical procedure was performed with 1.3-mm miniplates and screws (Response Ortho, Edgewater, NJ). A longitudinal incision was made on the anteromedial aspect of the left knee, and the medial aspect of the proximal tibial epiphysis was exposed. The physeal line was visible, so radiography was not needed during the operation. The periosteum was not elevated. In groups 1 and 3, the medial plate was placed at the maximum possible angle to the lateral axis of the tibia, with 1 hole proximal to the physeal line and posteriorly and 1 hole distal to the physeal line and anteriorly. The same incision was streched laterally; the extensor digitorum pedis longus tendon was exposed and elevated from its sulcus. The lateral plate was fixed with 1 hole proximal to the physeal line and anteriorly, and with 1 hole distal to the physeal line and posteriorly. The screws were not tightened completely (Figure 1). By avoiding full tightening of the screws, rotation of the plates around the screws during growth was possible. As the bone grew, the proximal part of the medial plate would move anteriorly, the proximal part of the lateral plate would move posteriorly, and thereby internal rotation would be achieved. A bone block was excised from the fibula in order to provide lengthening of the tibia free from the fibula. Animals in group 2 were operated with the same surgical technique, but only screws were placed onto the same implantation sites—without any plates. After the operation, acetaminophen (1–2 mg/kg of the drug per day) was added to the drinking water for 3 days.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative view of plate-screw application to the rabbit tibia. a. Medial view: orientation of the plate from proximal posterior to distal anterior. b. Anterior view. c. Lateral view: orientation of the plate from proximal anterior to distal posterior.

Radiographic assessments were carried out immediately after the operation and every 2 weeks. On the anteroposterior radiographs, the anatomic lateral distal femoral angle (LDFAng), the medial proximal tibial angle (MTAng), and the femorotibial angle (FTAng) were measured. All animals were killed with high doses of inhaled isoflurane after the follow-up period, and the hindlegs were disarticulated from the hip joint. After disarticulation, 1-mm-thick section images of the extremity, with 1 mm between the sections, were acquired with computed tomography (CT) (Toshiba scanner Aquilion prime TSX-303A/80 detector-160 section).

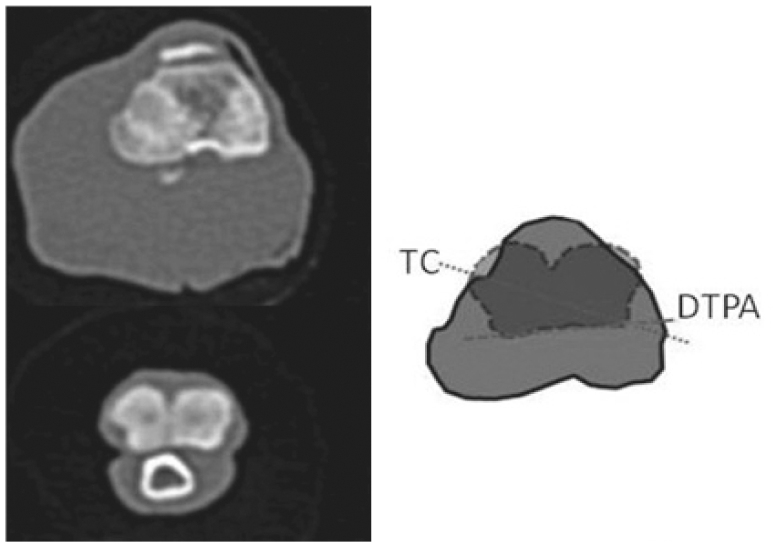

Because there is no certain tibial rotation profile in rabbits, the unoperated right lower extremity served as the control. The measurements were performed on the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). Because there are no previously determined axes for the tibial rotation in rabbits, axial cross sections from canine studies were taken as a basis. Tibial torsion was the angle between the transcondylar axis (the line between the posterolateral extension of the sulcus extensorius and the prominence of the medial collateral ligament insertion) and the distal posterior axis (the tangent passing from the posterior cortex of the distal tibia) (Aper et al. 2005, Mostafa et al. 2009, Fitzpatrick et al. 2011) (Figure 2). The external rotation of the distal reference line relative to the proximal reference line was accepted as a negative value. So the external rotation meant negative. After CT, the tibia was liberated from the soft tissues and the length of the tibia was measured with a compass.

Figure 2.

Measurement of tibial torsion on CT. TC: transcondylar axis; DTPA: distal tibial posterior axis.

Statistics

Because there has been no rotational value for rabbit tibia reported in the literature, the study was finalized when sufficient power was obtained. The power of the study was over 90%, with an effect size of 1.45, a type-I error rate of 0.05, and a type-II error rate of 10%. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of numeric variables. For the numeric variables that were normally distributed, comparison among groups was done with ANOVA and independent-samples t-test, and descriptive statistics are presented as mean (SD). For the numeric variables that were not normally distributed, comparison between groups was done with the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Mann-Whitney U-test, and descriptive statistics are presented as median (25th–75th percentile). When a difference was found between the groups, the Bonferroni test was applied as post-hoc test in order to determine which group caused the difference. Any p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

This experimental study was approved by the institutional review board (number 64583101/2013/049).

Results

The study was completed using 45 animals. In group 1, excluding unsuitable tibias for measurement due to excessive deformations in the sagittal and coronal planes, 7 left tibias were suitable for measurement. Mean torsion was −20° (SD 7.9) on the right and −2.9° (SD 7.2) on the left, the torsion of the left tibia had an average of 17° of internal rotation compared to the right (p < 0.001). In group 2, 15 tibias that were suitable for measurement were evaluated, and there was no statiscially significant difference between the right torsion of −23° (SD 4.9) and the left torsion of −26° (SD 6.5) (p = 0.2). In group 3, 14 tibias were suitable for measurement. The torsion was −21° (SD 6.3) on the right and −9.5° (SD 5.3) on the left, with the left tibia in more internal rotation than the right by an average of 11° (p < 0.001). Intergroup evaluation for torsion showed a significant difference between group 2 and the other 2 groups, but no significant difference between groups 1 and 3 (Tables 1 and 2, see Supplementary data).

There were no statistically significant differences in intergroup or intragroup comparisons for LDFAng. MPTAng and FTAng measurements showed a significant difference within group 1, and no difference within groups 2 and 3. Intergroup evaluation for MPTAng and FTAng showed no significant difference on the right, but there was a significant difference on the left (Tables 3 and 4). Tibial length showed intragroup differences in group 1 (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

Table 3.

Intragroup comparison of radiographic measurements in both lower extremities. Values are mean (SD) or median (range)

| Group | Radiographic measurements | Right | Left | p-value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LDFAng | 88 (5.3) | 92 (7.4) | 0.2 |

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| MPTAng | 80 (5.6) | 90 (4.1) | < 0.001 | |

| (n = 15) | (n = 14) | |||

| FTAng | 175 (6) | 162 (10.2) | < 0.001 | |

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| 2 | LDFAng | 92 (4.3) | 92 (6.9) | 0.9 |

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| MPTAng | 87 | 91 | 0.07 | |

| (85–91) | (88–94) | |||

| (n = 15) | (n =15) | |||

| FTAng | 175 | 178 | 0.2 | |

| (170–177) | (173–178) | |||

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| 3 | LDFAng | 90 (4.2) | 90 (5.8) | 0.9 |

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| MPTAng | 91 (3.6) | 89 (5.6) | 0.2 | |

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| FTAng | 177 (4.3) | 175 (3.5) | 0.2 | |

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) |

p-values determined with independent-samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test.

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison of both lower extremity radiographic measurements. Values are mean (SD) or median (range)

| Radiographic measurements | N | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | p-value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right MPTAng | 45 | 88 | 87 | 92 | 0.1 |

| (84–92) | (85–91) | (89–95) | |||

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| Left MPTAng | 44 | 80 (5.6) b | 92 (5) | 89 (5.6) | < 0.001 |

| (n = 14) | (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| Right LDFAng | 45 | 88 (5.3) | 92 (4.3) | 90 (4.1) | 0.2 |

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| Left LDFAng | 45 | 92 (7.4) | 92 (6.9) | 90 (5.8) | 0.7 |

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| Right FTAng | 45 | 175 | 175 | 177 | |

| (168–180) | (169–177) | (172–179) | 0.3 | ||

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | (n = 15) | |||

| Left FTAng | 45 | 162 | 178 | 175 | 0.001 |

| (158–167) c | (173–178) | (172–178) | |||

| (n = 15) | (n = 15) | (n = 15) |

p-values determined with Kruskal-Wallis test or ANOVA.

Group 1 was significantly different from group 2 (p < 0.001) and group 3 (p < 0.001).

Group 1 was significantly different from group 2 (p < 0.001) and group 3 (p = 0.010).

Early postoperative and follow-up radiographs of all groups are shown in Figures 3–5, see Supplementary data.

Discussion

There has been one previous study on the rotationally guided growth of the femur (Arami et al. 2013). These authors used the distal femur in rabbits, and in order to create an external rotation, they placed the plates in appropriate positions. But the plate could not be inserted into the medial femoral condyle in an appropriate position in the internal rotation group. The distal femur physeal line has wavy structure, which can hamper appropriate placement of the plate and increase the risk of physeal injury during surgery. We therefore used the proximal tibial epiphysis, which has a straighter physeal line. The surgical procedure was performed with 1.3-mm miniplates and screws, which did not damage the apophysis of the tibial tuberosity. The plates were inserted as obliquely as possible—as permitted by the anatomic properties of the proximal tibia and by plate size (collateral ligaments, apophysis of the tibial tuberosity, thickness of the physeal plate). In group 1, the decrease in the rotation (average 17°) supported the internal rotation effect of the plates. Arami et al. (2013) reported that an average of 18° of external rotation occurred in the femurs. In our study, only 7 of 15 rabbits could be evaluated for rotation. Because there were excessive deformities in the sagittal (anterior tibial slope) plane and the coronal (varus) plane in 8 tibias, they could not have been evaluated with CT.

According to various clinical and experimental studies investigating the effect of temporary epiphysiodesis on coronal plane deformities, changes that have been achieved may later return to baseline after implant removal, due to a rebound effect (Stevens 2007, Mast et al. 2008, Yilmaz et al. 2014). In order to test this, the implants were removed in group 3. In this group, the rotation of the tibia could not be assessed with CT immediately after removal of the plates. Attainment of rotation in group 1 made us think that rotation was also achieved in group 3 during the 1-month follow-up. Although there was a difference in mean tibial rotation between group 3 and group 1, this was not statistically significant. In group 3, the animals were 6 weeks old during the first operation, and 10 weeks old during the second. Because rabbits grow fast, the difference in the growth paces in the first 1-month period and the second 1-month period could have affected the rate of this rebound effect. There was a similarity between groups 1 and 3. Groups 1 and 3 were different from group 2. There was no rotational change in group 2. The other important issue is scar tissue over the implants. During the removal of implants, extensive scar tissue without bone overgrowth was encountered over the implants. After resection of scar tissue, the implants were loose but no implant failures were encountered. This scar tissue may limit rotation and cause undesired deformity in the sagittal and coronal planes. But during the implant removal, it was apparent that the distal screw of the medial plate moved too posterior relative to the first inserted point and the distal screw of lateral plate moved too anterior relative to the first inserted point. The plates were more vertical at the final stage than the position on the first postoperative radiograph. Arami et al. (2013) created a formula: 1° of change in the angle between the plates led to 0.4° of rotation. We did not use a formula. We believed that the angle between the plates was not the most critical consideration in our method, because when 1 plate is placed parallel to the long axis of the bone it will prevent growth of the bone and will lead to secondary deformity. Arami et al. (2013) reported that the additional deformity was one of the limitations of their study. Thus, insertion of these plates with the greatest possible angle to the long axis will lead to both greater rotation and safe controlled growth. The angle between the positions of the plate and the bone axis should be monitored.

We found a statistically significant difference between the right and left lengths in group 1. The lack of a difference in group 2 showed that use of a screw did not have any effect on length. The difference between groups 1 and 2 was caused by prevention of bone growth by the plates, which became parallel to the bone axis and prevented bone growth during the 4-week follow-up period. Considering that the values in group 1 at 1 month served as a reference for group 3, length discrepancy occurred in group 3 during the early period. After implant removal, there was no difference between the left and right legs in group 3. Scintigraphy and magnetic resonance studies have shown that osteoblast activity increases after plate removal; in other words, growth occurs (Gottliebsen et al. 2013, Komur et al. 2013). Arami et al. (2013) reported that the femur undergoing the actual operation was shorter than the other side with the sham operation. Komur et al. (2013) applied the temporary epiphysiodesis to the medial and lateral aspects of the rabbit tibia and found that there was a statistically significant difference between the lengths before removal of the implants, whereas there was no difference after removal of the implants.

Group 1 had an intragroup difference in MPTAng whereas groups 2 and 3 did not. Intergroup evaluation showed a difference in MPTAng for the left side and no difference for the right side. Group 3 showed values similar to those in groups 1 and 2. Also, there was no intragroup difference in group 3. All of these results indicate remodeling. Similarly, the similarity between groups 2 and 3 in FTAng indicates remodeling. In group 1, the medial plate became parallel to the long axis of the tibia earlier than the lateral plate, which created a varus effect.

The standard follow-up period in our study was 1 month. Mast et al. (2008) created tibial valgus deformity in rabbits and they reported that the deformity began to develop 1 week after the implantation of the plate or staple. In our study, because the plates were oblique, they could have led to a coronal plane deformity once they became parallel to the long axis of the tibia. Thus, such a follow-up period was not suitable in our study. We made the radiographic assessments immediately after the operation and every 2 weeks. The tibias were unsuitable for measurement of torsion, due to sagittal and coronal deformations in group 1. We recommend that because 6-week-old rabbits grow rapidly, a close radiographic follow-up (once a week) is necessary to prevent length discrepancies and deformities. With our method, plates can be inserted more horizontally in children because of larger bone. However, for use in children, the characteristic stages of growth from birth to adulthood must be known. Close clinical and radiographic follow-up is mandatory to prevent additional deformities or excessive correction during the period when the rate of growth increases rapidly.

The limitations of the present study were the absence of an external rotation group and the lack of preoperative and weekly CT controls because of technical difficulties. However, while designing the study we considered that the unoperated right lower extremity would compensate for the lack of preoperative CT. However, operating on only 1 extremity provided an advantage for evaluation of the changes in the operated side, because despite the common use of rabbits in orthopedic studies there are no standard measurement techniques and outcomes that can be taken as references for the tibia. The evaluations were based on canine studies (Aper et al. 2005, Mostafa et al. 2009, Fitzpatrick et al. 2011). Our study can therefore serve as a basis for future studies. The other issue is simultaneous correction of combined malalignments including valgus or varus and torsional malalignment. We had no group to investigate this pattern, but it may be possible if 1 of the plates is placed at a lesser angle to the lateral bone axis than the other.

In summary, our plate technique provided rotational change in the tibia in an animal model. Clinical application will require close clinical and radiological follow-up to disclose secondary deformities in the sagittal and coronal planes.

Supplementary data

Tables 1, 2, and 5, and Figures 3–5 are available at the Acta Orthopaedica website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 9577.

MC: design of the study, data collection, data analysis, editing, writing, and literature search. EC: design of the study, interpretation of data, and editing. FSK and RY: data collection. MKO: data analysis.

No competing interests declared.

We thank Professor Mehmet Erkut Kara and Associate Professor Imran Kurt for statistical advice when preparing this study. We are grateful to the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey for support (113S563).

References

- Aper R, Kowaleski M P, Apelt D, Drost W T, Dyce J.. Computed tomographic determination of tibial torsion in the dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2005; 46(3): 187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arami A, Bar-On E, Herman A, Velkes S, Heller S.. Guiding femoral rotational growth in an animal model. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 20; 95(22): 2022–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt R D, Herzenberg J E.. Temporary hemiepiphysiodesis with the eight-plate for angular deformities: mid-term results. J Orthop Sci 2010; 15(5): 699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda P, Urquhart B, Sullivan E, Haynes RJ.. Hemiepiphysiodesis for the correction of angulardeformity about the knee. J Pediatr Orthop 2008; 28(2): 188–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobeljic´ G, Djoric´ I, Bajin Z, Despot B.. Femoral derotation osteotomy in cerebral palsy: precise determination by tables. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 452: 216–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick C L, Krotscheck U, Thompson M S, Todhunter R J, Zhang Z.. Evaluation of tibial torsion in Yorkshire Terriers with and without medial patellar luxation. Vet Surg 2011; 41(8): 966–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottliebsen M, Møller-Madsen B, Stødkilde-Jørgensen H, Rahbek O.. Controlled longitudinal bone growth by temporary tension band plating: an experimental study. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B(6): 855–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyr B M, Colmer H G 4th, Morel M M, Ferski G J.. Hemiepiphysiodesis for correction of angular deformity in pediatric amputees. J Pediatr Orthop 2013; 33(7): 737–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatt J, Stevens P M.. Guided growth for fixed knee flexion deformity. J Pediatr Orthop 2008; 28(6): 626–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komur B, Coskun M, Komur A A, Oral A.. Permanent and temporary epiphysiodesis: an experimental study in a rabbit model. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2013; 47(1): 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast N, Brown N A, Brown C, Stevens P M.. Validation of a genu valgum model in a rabbit hind limb. J Pediatr Orthop 2008; 28(3): 375–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa A A, Griffon D J, Thomas M W, Constable P D.. Morphometric characteristics of the pelvic limbs of Labrador Retrievers with and without cranial cruciate ligament deficiency. Am J Vet Res 2009; 70(4): 498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palocaren T, Thabet A M, Rogers K, Holmes L Jr, Donohoe M, King M M, Kumar S J.. Anterior distal femoral stapling for correcting knee flexion contracture in children with arthrogryposis–preliminary results. J Pediatr Orthop 2010; 30(2): 169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton A M, Stevens P M, Hung M.. Guided growth for the treatment of moderate leg-length discrepancy. Orthopedics 2013; 36(5): e575–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A C. Treatment of infantile Blount disease with lateral tension band plating. J Pediatr Orthop 2012; 2(1): 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroerlucke S, Bertrand S, Clapp J, Bundy J, Gregg F O.. Failure of Orthofix eight-Plate for the treatment of Blount disease. J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29(1): 57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens P M. Guided growth for angular correction: a preliminary series using a tension band plate. J Pediatr Orthop 2007; 27: 253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton D M, Liu R W, Farrow L D, Thompson G H.. Proximal tibial derotation osteotomy for torsion of the tibia: a review of 43 cases. J Child Orthop 2012; 6(1): 81–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz G, Oto M, Thabet A M, Rogers K J, Anticevic D, Thacker M M, Mackenzie W G.. Correction of lower extremity angular deformities in skeletal dysplasia with hemiepiphysiodesis: a preliminary report. J Pediatr Orthop 2014; 34(3):336–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]