Abstract

Background and purpose

Results from case-control studies of maternal age at conception and risk of idiopathic clubfoot have been inconsistent. We conducted a meta-analysis to determine whether there is any association between maternal age at conception and the morbidity of idiopathic clubfoot.

Methods

We searched PubMed-MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library up to June 2015 and supplemented the search with manual searches of the reference lists of the articles identified. 11 studies published between 1990 and 2015 were pooled. We investigated heterogeneity in maternal age and whether publication bias might have affected the results.

Results

Compared to a control group, maternal age at conception of between 20 and 24 years old was associated with an increased risk of occurrence of clubfoot (OR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.1–1.4). No such association was found for the age groups of ≥ 35, 30–34, 25–29, and < 20 years. There was no heterogeneity in the age groups of ≥ 35, 30–34, and 20–24 years, moderate heterogeneity in the 25- to 29-year age group, and a large degree of heterogeneity in the group that was < 20 years of age. The prediction intervals for the age groups of 25–29 and < 20 years were 0.56 to 1.3 and −0.39 to 2.4, respectively. We found no evidence of significant publication bias.

Interpretation

From the results of this meta-analysis of 11 studies, maternal age at conception between 20 to 24 years of age appears to be associated with an increased risk of occurrence of clubfoot.

The precise etiology and pathogenesis of idiopathic clubfoot remain unclear, and many possible hypotheses have been considered—such as neuromuscular, bone, connective tissue, and vascular factors (Miedzybrodzka 2003). Epidemiological studies have consistently found a higher prevalence of idiopathic clubfoot in males and in first-born children, but the role of maternal age is unclear; the age of the mother has been reported to be either inversely or positively associated with clubfoot (Honein et al. 2000, Cardy et al. 2007, Dickinson et al. 2008, Kancherla et al. 2010), but other studies have found no association (Byron-Scott et al. 2005, Carey et al. 2005, Moorthi et al. 2005, Pavone et al. 2012, Skelly et al. 2002). This is of some interest, because the mean maternal age at conception has increased significantly in most countries during the past 2 decades, especially in developed countries.

We systematically evaluated the evidence from retrospective studies for the importance of maternal age at conception for the risk of idiopathic clubfoot, and quantified any association using meta-analysis.

Methods

Search strategy

A literature search was carried out in PubMed-MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library to identify the studies that assessed the association between maternal age at conception and risk of idiopathic clubfoot. We identified English language papers published before June 30, 2015, using the following search terms: “clubfoot” OR “talipes equinovarus” AND “maternal age”. Next, we carried out a manual search of the reference lists of retrieved papers to identify any other relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

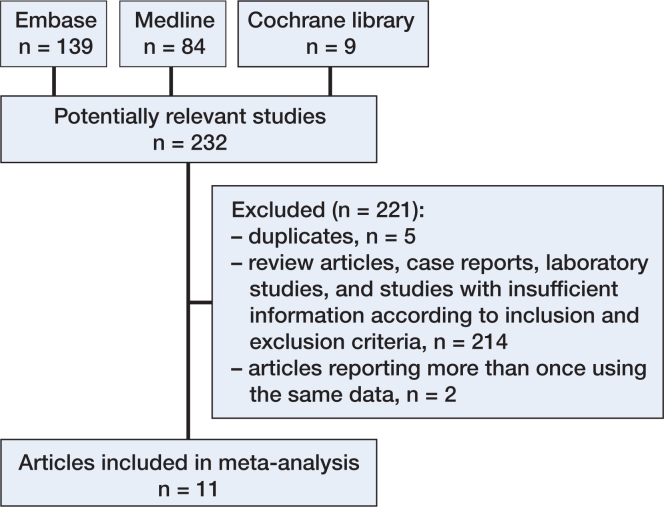

Studies were eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) definitive diagnosis of idiopathic clubfoot rather than other congenital deformities; (2) case-control or cohort study; (3) reporting of the results of maternal age at conception rather than delivery; (4) data usable for extraction and analysis of the odds ratio (OR). If the results of a particular study had been reported more than once, we included the latest report (Figure 1). We excluded studies that were otherwise eligible but which provided information on subjects with clubfoot that had been diagnosed and attributed to a known etiology, field detect, sequence, or syndrome. Papers written in languages other than English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish were also excluded.

Figure 1.

Selection of studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis of maternal age and risk of clubfoot, 1974–2015.

Quality assessment

The quality of a study was assessed with the 9-star Newcastle Ottawa Scale (Wells et al. 2000). 9 stars meant a full score, and a score of ≥ 6 stars was considered to be of high quality. The quality of case-control studies was assessed according to the following considerations: adequate definition of cases, representativeness of cases, selection of controls, definition of controls, control for the most important factor or the second important factor, exposure assessment, same method of ascertainment for all subjects, and non-response rate. The median study score of the 11 studies included was 7 (6–8) (Table 1, see Supplementary data).

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each report: the last name of the first author, the year of publication, the type of study design, the country or state, the time when the study was performed, maternal age (including details of the assessment), the odds ratio (OR), the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI), and confounding factors.

Statistics

For the studies included, we determined the pooled OR with 95% confidence interval (CI) for the maternal age groups versus control groups. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated with the I2 statistic (Higgins and Thompson 2002): I2 > 50% was considered statistically significant (Hedges and Pigott 2001). Here, we chose a random effects model to calculate the pooled OR and CI for more conservative results. If there was a moderate or large degree of heterogeneity between the studies included (with I2 > 25% as a guide (Higgins et al. 2003)), we calculated a prediction interval considering the potential effect within an individual study setting (Riley et al. 2011). We used visual inspection of funnel plots, Egger’s test, and Begg’s test to determine whether publication bias might have affected the statistical results (Begg et al. 1994, Egger and Smith 1998). All statistical analyses were conducted using Revman 5.3.5 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) and Stata 12.0. Any p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study characteristics

These studies were summarized according to the PRISMA statement checklist (Moher et al. 2009). A flow diagram of the search process is shown in Figure 1. 232 articles were identified through PubMed-MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. Of these, 5 duplicate articles were excluded, and a further 214 articles were excluded because they were review articles, case reports, or laboratory studies—or because they did not provide sufficient information according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After obtaining the full articles, we 2 other papers for using the same data (Olshan et al. 2003, Werler et al. 2013), leaving 11 articles that would be appropriate for the meta-analysis (Table 2, see Supplementary data). The 11 articles included were all case-control studies. Of the studies selected, 6 were conducted in the USA (Alderman et al. 1991, Honein et al. 2000, Skelly et al. 2002, Dickinson et al. 2008, Parker et al. 2009, Werler et al. 2015), 1 in Western Australia (Carey et al. 2005), 1 in the UK (Cardy et al. 2007), 1 in Vietnam (Nguyen et al. 2012), 1 in Peru (Palma et al. 2013), and 1 in Turkey (Sahin et al. 2013). 6 of the 11 studies presented ORs and 95% CIs for maternal age at conception (Carey et al. 2005, Cardy et al. 2007, Dickinson et al. 2008, Parker et al. 2009, Sahin et al. 2013, Werler et al. 2015). All of the studies presented different age groups (i.e. age less than 20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, and 35 or more years old) according to different study designs—except for 1 by Honein et al. (2000), which presented only 1 age group of 35 or more years old.

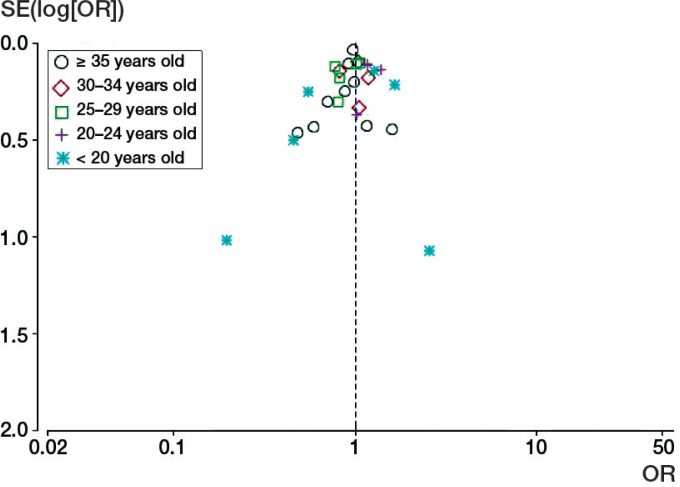

Group I (≥ 35 years of age)

9 case-control studies (Alderman et al. 1991, Honein et al. 2000, Skelly et al. 2002, Carey et al. 2005, Cardy et al. 2007, Parker et al. 2009, Nguyen et al. 2012, Palma et al. 2013, Werler et al. 2015) were included in this age group for meta-analysis and the ORs were compared with the reference group for each study. There was no evidence to support an association between maternal age of 35 or more years and increased risk of clubfoot (OR = 0.96, CI: 0.89–1.03; p = 0.3) (Figure 2, see Supplementary data). There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.6, I2 = 0%). The corresponding funnel plot appeared symmetrical (Figure 3), and there was no evidence of significant publication bias from Egger’s test (p = 0.5) and Begg’s test (p = 0.9).

Figure 3.

Funnel plots for different maternal age groups and the risk of clubfoot.

Group II (30–34 years of age)

4 studies (Skelly et al. 2002, Carey et al. 2005, Cardy et al. 2007, Werler et al. 2015) involving 4,754 mothers were included in the meta-analysis (1,525 in the clubfoot group and 3,229 in the control group). There was no evidence to support an association between a maternal age of 30–34 years and increased risk of clubfoot (OR = 0.99, CI: 0.85–1.1; p = 0.9) (Figure 2, see Supplementary data). There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.4, I2 = 0%). The funnel plot was symmetrical (Figure 3). Egger’s test and Begg’s test showed no evidence of significant publication bias (p = 0.9 and p = 0.7, respectively).

Group III (25–29 years of age)

5 studies (Skelly et al. 2002, Carey et al. 2005, Cardy et al. 2007, Dickinson et al. 2008, Werler et al. 2015) had data from this age group that were usable for meta-analysis. No association was found between a maternal age of 25–29 years and increased risk of clubfoot, with a pooled OR of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.8–1.1; p = 0.3) (Figure 2, see Supplementary data). There was little heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 27%, p = 0.2) and the 95% prediction interval was 0.56–1.3. The funnel plot appeared symmetrical (Figure 3). There was no evidence of significant publication bias according to Egger’s test (p = 0.4) and Begg’s test (p = 0.2).

Group IV (20–24 years of age)

4 studies (Skelly et al. 2002, Carey et al. 2005, Dickinson et al. 2008, Werler et al. 2015) involving 9,094 mothers were included (1,729 in the clubfoot group and 7,365 in the control group). The studies were published between 2005 and 2015. We calculated OR with corresponding CI according to the crude data reported. There was a significant association between a maternal age of 20–24 years and the risk of clubfoot (OR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.1–1.4; p = 0.006) (Figure 2, see Supplementary data). There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.7, I2 = 0%). The funnel plot appeared symmetrical (Figure 3). No evidence of significant publication bias was obtained from Egger’s test (p = 0.8) and Begg’s test (p = 0.7).

Group V (< 20 years of age)

6 case-control studies (Alderman et al. 1991, Carey et al. 2005, Cardy et al. 2007, Dickinson et al. 2008, Sahin et al. 2013, Werler et al. 2015) were used to calculate the pooled estimate for assessment of any association between a maternal age of < 20 years and the risk of clubfoot. However, no such association was found (OR = 0.9, 95% CI: 0.53–1.5; p = 0.7) (Figure 2, see Supplementary data). Significant heterogeneity was found among the studies (I2 = 74%) and the 95% prediction interval was −0.39 to 2.4. To investigate possible sources of heterogeneity among studies, we employed a sensitivity analysis of each study by the exclusion method. This did not change the results (I2 statistics from 59% to 79% and test for overall effect of p from 0.34 to 0.98). We did not conduct a subgroup analysis using the limited information from crude data provided by the studies included. No evidence of publication bias was found among the studies included, either by Begg’s test (p = 0.5) or by Egger’s test (p = 0.3), and no evidence was obtained from funnel plot (Figure 3).

Discussion

Whether or not maternal age is associated with the risk of clubfoot has been unlear. A recent population-based case-matched control study in Hungary from Csermely et al. (2015) showed a higher proportion of cases of clubfoot in offspring of mothers in the youngest age group (≤ 19 years), and a borderline excess of cases in offspring of mothers of older age (i.e. ≥ 35 years). Palma et al. (2013) reported an association between maternal age (of < 23 years) at conception and increased risk of clubfoot. Parker et al. (2009) also found that maternal age (of < 23 years) was associated with clubfoot. Similarly, a study by Nguyen et al. (2012) showed that young maternal age (of < 25 years old) was associated with increased risk of clubfoot. Dickinson et al. (2008) found a trend of increasing risk of clubfoot with decreasing maternal age, with women in the youngest age group (< 20 years) having the highest risk (OR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.1–2.2) relative to women aged 30 or more. Multivariate analysis by Mahan et al. (2014) revealed that the strongest predictor in prenatal detection was a maternal age of ≥ 35 years (OR = 3.5). 1 study showed a negative correlation between occurrence of clubfoot and maternal age of > 35 years (Kancherla et al. 2010). Hollier et al. (2000) reported a higher risk of clubfoot, diaphragmatic hernia, and cardiac defects in mothers of older age. However, the opposite results—with no association between maternal age at conception and risk of clubfoot—have also been reported (Alderman et al. 1991, Cardy et al. 2007, Cardy et al. 2011, Honein et al. 2000, Moorthi et al. 2005, Sahin et al. 2013).

The findings from this meta-analysis of 11 case-control studies were that a maternal age of 20–24 years old at conception was statistically significantly associated with increased incidence of clubfoot. There was a 20% higher risk of clubfoot than in the control group. We found no evidence that other maternal age groups were associated with an increased risk of clubfoot. We found no heterogeneity in maternal age groups of 35 years or more, 30–34 years, or 20–24 years, moderate heterogeneity in the 25- to 29-year age group, and a large degree of heterogeneity in the age group of less than 20 years. The prediction intervals for the age groups of 25–29 years and less than 20 years both overlapped the OR value of 1. After sensitivity analysis of these groups, the same results were observed, indicating that our meta-analysis was relatively stable. The source of heterogeneity in these 2 maternal age groups might be traced to different survey regions, racial variation, and confounding factors.

A strength of our meta-analysis was the large number of cases included (n = 15,242 in the clubfoot group and 97,041 in the control group). One limitation might be the possible effects of having only a small number of studies, as only 11 studies were included. We did not find any publication bias because of such effects, but Egger’s test is known to have low power when less than 20 studies are included in a meta-analysis (Sterne et al. 2000). By not adequately controlling for confounders, our findings may have been biased in either direction (i.e. an exaggeration or underestimation of the risk estimate).

A large degree of heterogeneity was found for the maternal age group of less than 20 years (I2 = 74%), but we did not conduct a subgroup analysis using the limited information from crude data provided by the studies included.

The risk of clubfoot may be attributed to sociodemographic factors, socioeconomic status, education status, social culture, and other factors. A possible explanation of why a maternal age of between 20 and 24 years of age would be associated with an increased incidence of clubfoot might be the first-born baby boom period in this age group. Epidemiological studies have consistently found a higher prevalence of idiopathic clubfoot in primiparous mothers (Honein et al. 2000, Skelly et al. 2002, Carey et al. 2005). Our meta-analysis suggests that there may be a negative correlation between the risk of clubfoot and higher maternal age. The reason may be attributed to the birth of another baby in a family, which leads to a decreased clubfoot risk at 25 or older years of maternal age. It has been suggested that the higher the parity of a pregnant woman, the lower the risk of clubfoot in the baby (Carey et al. 2005, Dickinson et al. 2008, Kancherla et al. 2010). The low risk of congenital clubfoot in mothers less than 20 years old may be explained by the higher incidence of abortion and miscarriage in this age group.

Supplementary data

Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 2 are available on Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 9564.

YBL and JD contributed substantially to the acquisition of data and drafted the article. JZ and ZKW analyzed and interpreted the extracted data. LZ contributed to the conception and design of the article. HL and XY conducted the literature review and extracted the data from the studies that were included. CLX was responsible for statistical testing.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Alderman B W, Takahashi E R, LeMier M K.. Risk indicators for talipes equinovarus in Washington State, 1987-1989. Epidemiology 1991; 2 (4): 289–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C B, Mazumdar M.. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994; 50 (4): 1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byron-Scott R, Sharpe P, Hasler C, Cundy P, Hirte C, Chan A, et al. A South Australian population-based study of congenital talipes equinovarus. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2005; 19 (3): 227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardy A H, Barker S, Chesney D, Sharp L, Maffulli N, Miedzybrodzka Z.. Pedigree analysis and epidemiological features of idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus in the United Kingdom: a case-control study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardy A H, Sharp L, Torrance N, Hennekam R C, Miedzybrodzka Z.. Is there evidence for aetiologically distinct subgroups of idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus? A case-only study and pedigree analysis. PLoS One 2011; 6 (4): e17895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey M, Mylvaganam A, Rouse I, Bower C.. Risk factors for isolated talipes equinovarus in Western Australia, 1980-1994. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2005; 19 (3): 238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson K C, Meyer R E, Kotch J.. Maternal smoking and the risk for clubfoot in infants. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2008; 82 (2): 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith G D.. Bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ 1998; 316 (7124): 61–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L V, Pigott T D.. The power of statistical tests in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods 2001; 6 (3): 203–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J P, Thompson S G.. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21 (11): 1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J P, Thompson S G, Deeks J J, Altman D G.. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj 2003; 327 (7414): 557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honein M A, Paulozzi L J, Moore C A.. Family history, maternal smoking, and clubfoot: an indication of a gene-environment interaction. Am J Epidemiol 2000; 152 (7): 658–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kancherla V, Romitti P A, Caspers K M, Puzhankara S, Morcuende J A.. Epidemiology of congenital idiopathic talipes equinovarus in Iowa, 1997-2005. Am J Med Genet A 2010; 152A (7): 1695–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedzybrodzka Z. Congenital talipes equinovarus (clubfoot): a disorder of the foot but not the hand. J Anat 2003; 202 (1): 37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D G.. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthi R N, Hashmi S S, Langois P, Canfield M, Waller D K, Hecht J T.. Idiopathic talipes equinovarus (ITEV) (clubfeet) in Texas. Am J Med Genet A 2005; 132A (4): 376–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M C, Nhi H M, Nam V Q, Thanh do V, Romitti P, Morcuende J A.. Descriptive epidemiology of clubfoot in Vietnam: a clinic-based study. Iowa Orthop J 2012; 32: 120–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshan A F, Schroeder J C, Alderman B W, Mosca V S.. Joint laxity and the risk of clubfoot. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2003; 67 (8): 585–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma M, Cook T, Segura J, Pecho A, Morcuende J A.. Descriptive epidemiology of clubfoot in Peru: a clinic-based study. Iowa Orthop J 2013; 33: 167–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker S E, Mai C T, Strickland M J, Olney R S, Rickard R, Marengo L, et al. Multistate study of the epidemiology of clubfoot. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009; 85 (11): 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavone V, Bianca S, Grosso G, Pavone P, Mistretta A, Longo M R, et al. Congenital talipes equinovarus: an epidemiological study in Sicily. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (3): 294–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley R D, Higgins J P, Deeks J J.. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. Bmj 2011; 342: d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin O, Yildirim C, Akgun R C, Haberal B, Yazici A C, Tuncay I C.. Consanguineous marriage and increased risk of idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus: a case-control study in a rural area. J Pediatr Orthop 2013; 33 (3): 333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelly A C, Holt V L, Mosca V S, Alderman B W.. Talipes equinovarus and maternal smoking: a population-based case-control study in Washington state. Teratology 2002; 66 (2): 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J A, Gavaghan D, Egger M.. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53 (11): 1119–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa, Ontario The Ottawa Health Research Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Werler M M, Yazdy M M, Mitchell A A, Meyer R E, Druschel C M, Anderka M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of idiopathic clubfoot. Am J Med Genet A 2013; 161A (7): 1569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werler M M, Yazdy M M, Kasser J R, Mahan S T, Meyer R E, Anderka M, et al. Maternal cigarette, alcohol, and coffee consumption in relation to risk of clubfoot. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2015; 29 (1): 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]