Abstract

Background and purpose

Childhood fractures are associated with lower peak bone mass (a determinant of osteoporosis in old age) and higher adult fracture risk. By examining time trends in childhood fracture epidemiology, it may be possible to estimate the vector of fragility fracture risk in the future.

Patients and methods

By using official inpatient and outpatient data from the county of Skåne in Sweden, 1999–2010, we ascertained distal forearm fractures in children aged ≤ 16 years and estimated overall and age- and sex-specific rates and time trends (over 2.8 million patient years) and compared the results to earlier estimations in the same region from 1950 onwards.

Results

During the period 1999–2010, the distal forearm fracture rate was 634 per 105 patient years (750 in boys and 512 in girls). This was 50% higher than in the 1950s with a different age-rate distribution (p < 0.001) that was most evident during puberty. Also, within the period 1999–2010, there were increasing fracture rates per 105 and year (boys +2.0% (95% CI: 1.5–2.6), girls +2.4% (95% CI: 1.7–3.1)).

Interpretation

The distal forearm fracture rate in children is currently 50% higher than in the 1950s, and it still appears to be increasing. If this higher fracture risk follows the children into old age, numbers of fragility fractures may increase sharply—as an upturn in life expectancy has also been predicted. The origin of the increase remains unknown, but it may be associated with a more sedentary lifestyle or with changes in risk behavior.

Almost half of all boys and one third of all girls sustain a fracture during childhood, most commonly in the distal forearm (Hedström et al. 2010, Mayranpaa et al. 2010). There is recent evidence to suggest that a childhood fracture is a predictor of lower adult bone mass and increased risk of fracture in adulthood (Amin et al. 2013, Buttazzoni et al. 2013). As estimations suggest that 50% of the children born today will live to be at least 100 years old (Christensen et al. 2009), current fracture rates may provide important clues to the burden of adult fractures in the future.

The epidemiology of forearm fractures in children has been described earlier (Alffram and Bauer 1962, Landin 1983, Tiderius et al. 1999, Khosla et al. 2003), but only a few large studies have been published recently (Hedström et al. 2010, de Putter et al. 2011, Wilcke et al. 2013)—and very few with long-term time trends (Khosla et al. 2003).

In this paper we describe the current epidemiology and recent time trends in distal forearm fractures in children in southern Sweden, and we relate these results to older fracture data involving children, which are relevant to those at risk of fragility fractures today (current age up to 80 years).

Patients and methods

The Skåne Healthcare Register (SHR) covers all inpatient and outpatient healthcare provided to residents in Skåne, the southernmost county of Sweden. For the period 1999 to 2010, we used the SHR to identify all forearm fractures in individuals who were ≤ 16 years old and who resided in the region (corresponding to 2.8 million person years at risk) by using physician-set diagnostic codes according to the Swedish version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10 system (S52.50, S52.51, S52.60, S52.61). The washout period was set to 1 year (365 days) for each forearm fracture and unique individual, and we therefore also included data from 1998 as a reference for washouts in 1999. To estimate persons at risk (for each sex and each 1-year age class) during each individual year of observation, we used the average of the population at the start of the year (December 31 in the year before) and at the end of the year (December 31 in the year of interest), obtained from Statistics Sweden. The denominator for the overall incidence estimations (1999–2010) was estimated in person years, by summing up the estimates above for each of the years under consideration (1999–2010). For estimation of temporal trends in rates, we tabulated data by year and used Poisson regression of annual crude as well as annual direct age-standardized incidence rates (with the average annual population during the years examined as the standard population). Results are presented as annual percentage (%) change with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Differences in age-rate distribution between periods were examined by Poisson regression with incidence as dependent variable and time and period as factors with interaction.

The validity of the SHR in terms of distal forearm fractures has been examined previously. The register had a sensitivity of 90% and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 94% compared to a gold standard (Rosengren et al. 2015).

To allow comparison with more distant time points, we retrieved older fracture data (collected from manual review of charts and/or radiographs) from previously published studies on fractures in children in Malmö (Alffram and Bauer 1962, Landin 1983, Tiderius et al. 1999), which is the largest city in Skåne.

The study only involved coded (de-identified) data. We used SAS system version 9.2, SPSS version 17.0, and Microsoft Excel 2003 for data management and statistical calculations. All tests were 2-tailed and we considered that any p-value of less than 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

During the 12-year examination period, we found 17,686 distal forearm fractures (10,727 in boys and 6,959 in girls) over 2.8 million person years (1.4 million person years for boys and the same for girls). Compared to the year 1999, there were 18% more fractures in 2010 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Population annually and number of distal forearm fractures for each sex in children ≤ 16 years of age in Skåne, Sweden, from 1999 through 2010

| Boys | Girls | All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | No. of fractures | Population | No. of fractures | Population | No. of fractures |

| 1999 | 118,200 | 791 | 112,569 | 477 | 230,769 | 1,268 |

| 2000 | 118,317 | 804 | 112,710 | 575 | 231,027 | 1,379 |

| 2001 | 118,490 | 776 | 112,975 | 546 | 231,465 | 1,322 |

| 2002 | 118,749 | 902 | 113,194 | 545 | 231,943 | 1,447 |

| 2003 | 118,957 | 917 | 113,222 | 620 | 232,179 | 1,537 |

| 2004 | 119,074 | 983 | 113,076 | 626 | 232,150 | 1,609 |

| 2005 | 118,882 | 891 | 112,772 | 591 | 231,654 | 1,482 |

| 2006 | 118,951 | 910 | 112,796 | 587 | 231,747 | 1,497 |

| 2007 | 119,393 | 975 | 113,078 | 576 | 232,470 | 1,551 |

| 2008 | 119,861 | 986 | 113,457 | 590 | 233,318 | 1,576 |

| 2009 | 120,510 | 916 | 114,167 | 611 | 234,676 | 1,527 |

| 2010 | 121,333 | 876 | 114,843 | 615 | 236,176 | 1,491 |

| Total | 1,430,716 | 10,727 | 1,358,858 | 6,959 | 2,789,573 | 17,686 |

The overall distal forearm fracture rate during the 12-year study period was 634 per 105 patient years (750 in boys and 512 in girls), but time trends were evident with a statistically significant increase in overall age-standardized rate of +2.2% (95% CI: 1.7–2.6) per 105 and year (+2.0% (95% CI: 1.5–2.6) for boys and +2.4% (95% CI: 1.7–3.1) for girls) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall wrist fracture incidence rate (per 105 person years) and average crude and age-standardized annual change in incidence rate during the period 1999–2010 in children ≤ 16 years of age in Skåne, Sweden. 95% CI within parentheses

| Average annual change in rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall rate | Crude | Age-standardizeda | |

| Boys | 750 (711–788) | +1.2% (0.7–1.8) | +2.0% (1.5–2.6) |

| Girls | 512 (489–535) | +1.2% (0.5–1.9) | +2.4% (1.7–3.1) |

| Total | 634 (606–662) | +1.2% (0.8–1.7) | +2.2% (1.7–2.6) |

The average annual population during the years examined was used as the standard population.

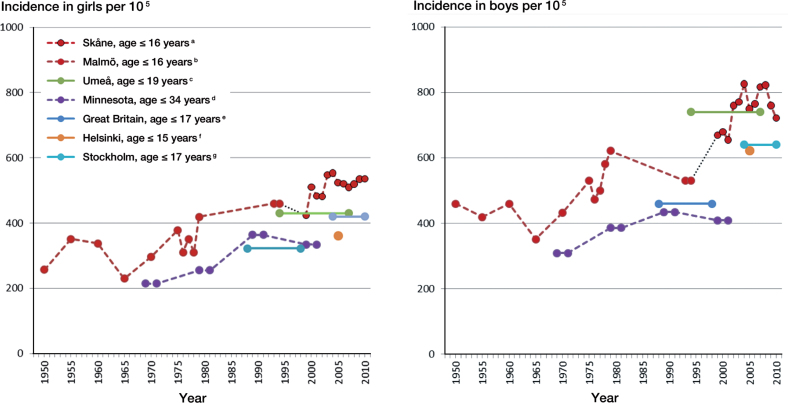

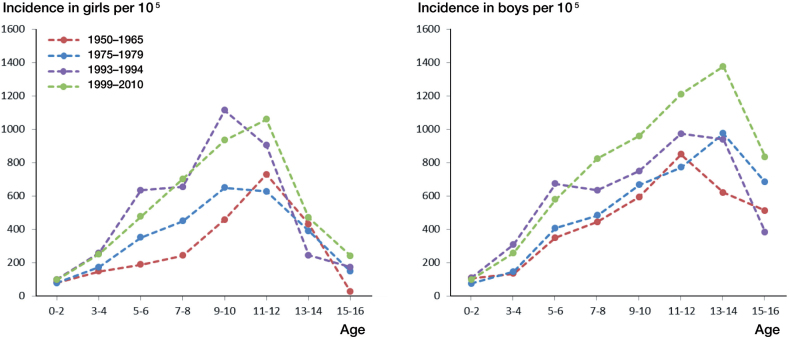

Compared to earlier (i.e. the period 1950–1994), the current distal forearm fracture rate was high (Figures 1 and 2). The children of today (examination period 1999–2010, born in the period 1982–2010) had a 50% higher incidence rate of distal forearm fractures than their counterparts who were examined during the period 1950–1965 (i.e. born in the period 1933–1965). The age-specific difference was most evident during puberty (Figure 2), with a different age-rate distribution (Poisson interaction between curves, p < 0.001). Sex-specific analyses revealed that this difference was already evident in 1993–1994 for girls, but only in the most recent period for boys (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Incidence of distal forearm fractures in girls and boys per 105, in different settings and time periods. a Current study. b Allfram and Bauer 1962, Landin 1983, Tiderius et al. 1999. c Hedström et al. 2010. d Khosla et al. 2003. e Cooper et al. 2004. f Mayranpaa et al. 2010. g Wilcke et al. 2013.

Figure 2.

Sex and age class-specific incidence of distal forearm fracture per 105 during different periods in children ≤ 16 years of age in Malmö (1950–1994; Allfram and Bauer 1962, Landin 1983, Tiderius et al. 1999) and in the county of Skåne (1999–2010; current study), in 2-year age class strata.

Discussion

In our study involving 2.8 million person years during the period 1999–2010 in a Swedish childhood population (≤ 16 years of age), we found a high incidence of distal forearm fractures—50% higher than during the period 1950–1965 (Alffram and Bauer 1962, Landin 1983, Tiderius et al. 1999). Also, within the examination period 1999–2010, the age-standardized incidence increased statistically significantly in both boys and girls (Table 2).

In a recent study from northern Sweden based on the years 1993–2007, Hedström et al. (2010) reported distal forearm fracture rates in children (≤ 19 years) of 740 per 105 person years in boys and 430 per 105 person years in girls, which are figures similar to ours. Since they ascertained fractures through radiographs and medical charts (the gold standard), not registry data, direct comparison with our study must be done with caution, yet the concordance of rates strengthens the usefulness of such comparisons (Figure 1).

In another Swedish registry-based study from Stockholm, Wilcke et al. (2013) reported an overall incidence for children who were ≤ 17 years old of 530 per 105 person years, and there were decreasing incidence rates from 2004 to 2010. Their results must be interpreted with care, however, as only 1 fracture per individual was counted, giving a decreasing population at risk over successive years without any corresponding decrease in the denominator—and without adjustment for lower risks in those who remained eligible.

Internationally, few recent epidemiological studies have focused on distal forearm fractures in children and young adults. In a study based on evaluation of medical records from the years 1999 to 2001 in Olmstead County, Minnesota, Kohsla et al. (2003) reported an age-adjusted incidence in younger men and women (≤ 34 years old) of 409 and 334 per 105 person years, respectively. These rates are lower than ours, but since the incidence of distal forearm fractures decreases considerably after adolescence in both sexes (Buhr and Cooke 1959, Rosengren et al. 2015), the age span 0–34 years in their study would give lower rates than studies with an upper age limit in late teenage. Interestingly, Kohsla et al. (2003) also reported a higher incidence of distal forearm fractures in both sexes in people aged ≤ 34 years during the period 1999–2001 than during the period 1969–1971.

In another report, a registry-based study from the Netherlands, de Putter et al. (2011) reported that the incidence of wrist fractures in boys and girls aged 5–14 years increased from 1997 to 2007, but they did not present any overall rates for the examination period.

In Finland, in an examination of overall fracture epidemiology in children (< 16 years), Mayranpaa et al. (2010) examined charts and radiographs from a single large center in Helsinki and reported a distal radius fracture rate of 622 per 105 in boys and 361 per 105 in girls over a 12-month period (2005–2006). Despite the fact that they found a decreasing overall fracture rate from 1983 to 2005, the distal radius fracture rate increased by more than 30%.

In Norway, in a prospective 12-month study of children 0–16 years of age in 2010–2011, Randsborg et al. (2013) found an overall incidence of distal radius fractures of 560 per 105. The method included evaluation of radiographs and medical charts.

In a study from Britain, Cooper et al. (2004) used the General Practice Research Database to determine the overall fracture epidemiology in children (< 18 years) from 1988 to 1998, and they found a rate of radius/ulna fracture (not specifically distal forearm fracture) of 460 per 105 for boys and 322 for girls. This may seem low compared to our results, but as they also included 17-year-olds and only registered 1 fracture per individual, it may be similar to our results. There was, however, also a separate category of green stick fractures with a rate of 173 and 155 per 105, and it is not clear whether or not these fractures were included in the rate of radius/ulna fractures.

In New Zealand, in a small single-center study over a 12-month period (1994–1995 for girls and 1998–1999 for boys), Jones et al. (2000) found wrist fracture rates of about 1,000 per 105, which were similar in boys and girls (aged 3–15 years). Why their rates were higher than in other studies is still unclear, but this may partly be explained by the small study size and by the fact that there are very few children aged 0–2 with wrist fracture.

The rates and the recent increase in distal forearm fracture rates for both boys and girls in our study are in line with previous reports as mentioned above (Khosla et al. 2003, Hedström et al. 2010, Mayranpaa et al. 2010, de Putter et al. 2011), but the major long-term increase in rates that we identified has not been presented before.

Some authors have suggested that the level of physical activity has had a major role in the change in fracture incidence in children (Tiderius et al. 1999, Hedström et al. 2010, de Putter et al. 2011), but there is conflicting evidence in the literature regarding the connection between physical activity and fracture risk. Clark et al. (2008) found a positive association between a high level of physical activity and fracture risk in children aged 9–11 years, while Detter et al. (2013) found no increase in fracture risk in a long-term moderate exercise intervention program in schoolchildren. Physical activity in childhood is, however, also known to increase peak bone mass (Karlsson et al. 2008), which in turn probably prevents low bone mineral density later in life (Hui et al. 1990). Even more interesting is that childhood fracture appears to be associated with low bone mineral density in young adulthood (Ferrari et al. 2006, Buttazzoni et al. 2013, Farr et al. 2014)—at least in boys—and also a higher risk of fragility fracture later in life (Amin et al. 2013).

Data from a randomized prospective study in schoolchildren (the POP study), where the intervention group received more physical education, indirectly support the notion that low physical activity may be responsible (Fritz et al. 2015). They found the usual age trend, with a higher fracture rate during puberty in the controls but not in the intervention children. This indicates that their study intervention probably addressed at least one of the factors responsible for the temporal increments in risk that we found, especially evident during the initial pubertal period (Figure 2).

It should be emphasized that it has not yet been established whether children who have fractures carry an increased risk of fracture with them into adulthood and old age (Ferrari et al. 2006), but as mentioned above, there is a fair amount of evidence in favor of this (Amin et al. 2013, Buttazzoni et al. 2013, Farr et al. 2014).

As 50% of the children born today have been projected to live to their hundredth birthday (Christensen et al. 2009), and as fragility fracture rates increase in old age (Rosengren et al. 2015), the increasing rate of distal forearm fractures in children is worrying. Previous studies have indicated that a childhood fracture predicts both lower adult bone mass and higher risk of fragility fracture in adulthood (Amin et al. 2013, Buttazzoni et al. 2013). As the children of today grow old, the prevalence of high fracture risk in the elderly may increase—and this, together with the anticipated increase in lifespan, could give a sharp increase in the number of fragility fractures in the future.

The origin of the increase in distal forearm fractures in children remains to be elucidated, but it may be associated with a change in lifestyle. A more sedentary childhood with digital amusements, less organized and spontaneous physical activity, and changes in risk behavior may lead to changes in, for example, bone strength (or specific bone traits), muscle strength, balance, risk of falling, vitamin D levels, BMI, diet, or factors that are yet to be discovered. Certain activities that have become popular in recent years such as skateboarding, trampoline jumping, and mountain biking may also have contributed to a higher risk of trauma. Inability to find and address the factors responsible may lead to an even higher incidence of childhood fractures and of fragility fractures in the future. Some clues may be simple to gather from already collected, older normative or control group data from previous studies, but unfortunately we do not have access to such data.

The strengths of the present study include the well-defined complete and large population of children followed over a long period (12 years) with data from a register validated (with good results) for distal forearm fractures (Rosengren et al. 2015), though not specifically for children. The examination of registers rather than individual patients, charts, or radiographs makes selection bias (random or systematic) possible. However, our results are very similar to those of Hedström et al. (2010), who used the gold standard of chart and radiograph review in a Swedish setting. We have no indication of any changes in diagnosis coverage of distal forearm fractures between 1999 and 2010, but this cannot be ruled out. However, any change—if present—would undoubtedly be towards better coverage. This would result in an underestimation of the overall period rate and a falsely low difference compared to earlier decades. It could, however, also result in an overestimation of the time-dependent increment in rates between 1999 and 2010. We set the washout period to 1 year, as the vast majority of distal forearm fractures would have healed by then and would therefore not appear in the medical records again as a result of that fracture. Consequently, if an individual was to appear in the register again, after more than a year (from the previous fracture diagnosis), with the same diagnosis, the most likely reason would be a new fracture, and the fracture would be counted as a new fracture. However, simultaneous bilateral fractures would be counted as only 1 fracture, as the register does not include information about side (left or right). It would have been preferable to have had data collection from the same geographical area by the same ascertainment method throughout the 60-year period, but this was not possible. It could be argued that the threshold for seeking medical treatment more than 60 years ago may have been higher than it is today, possibly resulting in falsely low rates long ago. Due to patient demands, physicians today may also be more liberal with radiological examinations, thereby also identifying minor torus or greenstick fractures that would not have been registered 50 years ago. Since most distal forearm fractures are associated with significant pain, those cases are probably few and their contribution to rates low.

The current rate of distal forearm fractures in Swedish children is high, and 50% higher than in the 1950s. If the increase in fracture risk follows the present children as they grow old, this may lead to a sharp increase in the number of fragility fractures—specially as a radical upturn in life expectancy in the not-too-distant future has been predicted. The origin of the increase in the rate of children’s distal forearm fractures remains to be elucidated, but it may be caused by a more sedentary lifestyle with digital amusements and less organized and spontaneous physical activities—and it could also be related to changes in risk behavior.

After a joint discussion between the authors, BR designed the study. BR and ME extracted the original data and then DJ did all the calculations. DJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and edited it—first together with BR and then together with all the authors. All the authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

Funding was received from the Swedish Research Council, from Government Funding of Clinical Research within the National Health Service (ALF), from FoU Skåne, from the Herman Järnhardt Foundation, from the Johan and Greta Kock Foundation, and from the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Sweden.

References

- Alffram P A, Bauer G C.. Epidemiology of fractures of the forearm. A biomechanical investigation of bone strength. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1962; 44-A: 105–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin S, Melton 3rd L J, Achenbach S J, Atkinson E J, Dekutoski M B, Kirmani S, et al. A distal forearm fracture in childhood is associated with an increased risk for future fragility fractures in adult men, but not women. J Bone Miner Res 2013; 28(8): 1751–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr A J, Cooke A M.. Fracture patterns. Lancet. 1959; 1(7072): 531–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttazzoni C, Rosengren B E, Tveit M, Landin L, Nilsson J A, Karlsson M K.. Does a childhood fracture predict low bone mass in young adulthood? A 27-year prospective controlled study. J Bone Miner Res 2013; 28(2): 351–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel J W.. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 2009; 374(9696): 1196–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E M, Ness A R, Tobias J H.. Vigorous physical activity increases fracture risk in children irrespective of bone mass: a prospective study of the independent risk factors for fractures in healthy children. J Bone Miner Res 2008; 23(7): 1012–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Dennison E M, Leufkens H G, Bishop N, van Staa T P.. Epidemiology of childhood fractures in Britain: a study using the general practice research database. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19(12): 1976–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Putter C E, van Beeck E F, Looman C W, Toet H, Hovius SE, Selles R W.. Trends in wrist fractures in children and adolescents, 1997-2009. J Hand Surg Am 2011; 36(11): 1810–5 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detter F T, Rosengren B E, Dencker M, Nilsson J A, Karlsson M K.. A 5-year exercise program in pre- and peripubertal children improves bone mass and bone size without affecting fracture risk. Calcif Tissue Int 2013; 92(4): 385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr J N, Amin S, Melton 3rd L J, Kirmani S, McCready L K, Atkinson E J, et al. Bone strength and structural deficits in children and adolescents with a distal forearm fracture resulting from mild trauma. J Bone Miner Res 2014; 29(3): 590–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S L, Chevalley T, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R.. Childhood fractures are associated with decreased bone mass gain during puberty: an early marker of persistent bone fragility? J Bone Miner Res 2006; 21(4): 501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz J, Cöster M E, Nilsson J, Rosengren B E, Dencker M, Karlsson M K.. The associations of physical activity with fracture risk-a 7-year prospective controlled intervention study in 3534 children. Osteoporos Int 2015. Sep 10. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedström E M, Svensson O, Bergstrom U, Michno P.. Epidemiology of fractures in children and adolescents. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(1): 148–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui S L, Slemenda C W, Johnston Jr C C.. The contribution of bone loss to postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 1990; 1(1): 30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I E, Cannan R, Goulding A.. Distal forearm fractures in New Zealand children: annual rates in a geographically defined area. N Z Med J 2000; 113(1120): 443–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M K, Nordqvist A, Karlsson C.. Physical activity increases bone mass during growth. Food Nutr Res 2008; 52. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v52i0.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla S, Melton 3rd L J, Dekutoski M B, Achenbach S J, Oberg A L, Riggs B L.. Incidence of childhood distal forearm fractures over 30 years: a population-based study. JAMA. 2003; 290(11): 1479–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landin L A. Fracture patterns in children. Analysis of 8,682 fractures with special reference to incidence, etiology and secular changes in a Swedish urban population 1950-1979. Acta Orthop Scand 1983; Suppl202: 1–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayranpaa M K, Makitie O, Kallio P E.. Decreasing incidence and changing pattern of childhood fractures: A population-based study. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25(12): 2752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randsborg P H, Gulbrandsen P, Benth J S, Sivertsen E A, Hammer O L, Fuglesang H F S, Årøen A.. Fractures in children: epidemiology and activity-specific fracture rates. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95: e42(1-7). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren B E, Karlsson M, Petersson I, Englund M.. The 21st-century landscape of adult fractures: cohort study of a complete adult regional population. J Bone Miner Res 2015; 30(3): 535–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiderius C J, Landin L, Duppe H.. Decreasing incidence of fractures in children: an epidemiological analysis of 1,673 fractures in Malmo, Sweden, 1993-1994. Acta Orthop Scand 1999; 70(6): 622–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcke M K, Hammarberg H, Adolphson P Y.. Epidemiology and changed surgical treatment methods for fractures of the distal radius: a registry analysis of 42,583 patients in Stockholm County, Sweden, 2004-2010. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(3): 292–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]