Abstract

Physical inactivity is one of the factors contributing to disproportionate disease rates among older African Americans. Previous literature indicates that older African Americans are more likely to live in racially segregated neighborhoods and that racial residential segregation is associated with limited opportunities for physical activity. A cross-sectional mixed methods study was conducted guided by the concept of therapeutic landscapes. Multilevel regression analyses demonstrated that racial residential segregation was associated with more minutes of physical activity and greater odds of meeting physical activity recommendations. Qualitative interviews revealed the following physical activity related themes: aging of the neighborhood, knowing your neighbors, feeling of safety, and neighborhood racial identity. Perceptions of social cohesion enhanced participants’ physical activity, offering a plausible explanation to the higher rates of physical activity found in this population. Understanding how social cohesion operates within racially segregated neighborhoods can help to inform the design of effective interventions for this population.

Disparate rates of physical activity between African Americans and European Americans have been widely documented (Landrine & Corral, 2009; Robert & Ruel, 2006; Satcher, 2001; Siegel, Ward, Brawley, & Jemal, 2011). Nationally, 26% of African Americans over the age of 65, and 37% of those aged 45–64, reported meeting physical activity recommendations in comparison with 41% of European American adults over age 65 and 49% of European American adults aged 45–64 (Gallagher et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2007). Differences in the rates of physical activity between these two groups have been offered as one plausible explanation for health outcome disparities (Bopp et al., 2006; Bopp et al., 2007; Powell, Martin, & Chowdhury, 2003).

These differences have recently been linked to external and environmental factors. Among older African Americans, aspects of the neighborhood environment that have been found to be associated with walking include neighborhood safety, seeing familiar faces, accessible sidewalks, and neighborhood aesthetics (Gallagher et al., 2010). Neighborhood physical disorder has been shown to be negatively associated with physical activity among older adults (Kwarteng, Schulz, Mentz, Zenk, & Opperman, 2014). However, there is little research showing the association of racial residential segregation to physical activity among African Americans 50 years and older.

Racial residential segregation is defined as the physical separation of races in a residential context, which over time has resulted in differential access to resources and societal opportunities (Acevedo-Garcia, Lochner, Osypuk, & Subramanian, 2003; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003; Karlsen & Nazroo, 2002). Racial residential segregation in the United States can be traced back to the migration of African Americans from the rural South to urban areas in search of jobs at the beginning of the 20th century (Massey & Denton, 1993). As African Americans found housing in urban neighborhoods, European American residents began moving to suburban areas, which produced inner-city neighborhoods with concentrations of African American residents (Massey & Denton, 1993; Massey, Gross, & Shibuya, 1994). This emergence of predominantly African American neighborhoods gave rise to the banking industry’s practice of “redlining,” which restricted loan approvals for housing in areas considered high risk, (i.e., neighborhoods that could potentially become predominantly African American) (Massey & Denton, 1993). As a result, financial investments flowed to European American suburban neighborhoods, bypassing urban African American neighborhoods and leading to a decline in property values and increase in foreclosures, forcing African Americans out of their homes into crowded public housing projects (Bond Huie, 2000; Massey & Denton, 1993). In addition, African American homeownership was lower in racially segregated neighborhoods as compared with predominantly European American neighborhoods due to older and poorer quality housing (Flippen, 2001). Although redlining is no longer practiced, racial residential segregation continues to restrict access to quality education and employment opportunities, resulting in unequal distribution of goods and services and limited access to resources needed for health promotion (Williams & Collins, 2001). One framework that can be used to describe how racial residential segregation may affect access to health-promoting resources is the place stratification model.

Place Stratification Model

The place stratification model posits that residential patterns are based on a hierarchy and are shaped by prejudice and discrimination. There is a hierarchy of places, classified by their desirability and the quality of life afforded to their residents (Freeman, 2000). Characteristics of desirable places can include owner-occupied housing, access to local goods and services, and protection from crime (Freeman, 2000). By living and owning homes in these desirable places, people who hold the power in the society maintain this power by distancing themselves spatially and socially from their minority counterparts (Alba & Logan, 1993; Freeman, 2000; Friedman, Singer, Price, & Cheung, 2005; Iceland & Wilkes, 2006). The place stratification model is most relevant in describing residential segregation patterns between African Americans and European Americans because it reflects more of the historical context that exists between the two groups (Freeman, 2000). The place stratification model informed the current study because it offers a mechanism by which racial residential segregation may be associated with physical activity through limited access to physical activity resources.

Research has shown that racial segregation is associated with poor health outcomes for African Americans living in these areas. An increase in lifetime exposure to racial residential segregation has also been connected to higher rates of mortality among African Americans, which is especially concerning for older African Americans who are more likely to live in these areas (Williams, 2001; LaVeist, 2003). While racial residential segregation negatively influences health, studies have also demonstrated that social cohesion can buffer the harmful effects of living in a racially segregated neighborhood (Bell, Zimmerman, Almgren, Mayer, & Huebner, 2006). Social cohesion is defined as close ties, trust, and shared values among neighbors (Fisher, Li, Michael, & Cleveland, 2004). Understanding the mechanisms by which racial residential segregation influences the physical activity of older African Americans is important to identify opportunities for intervention.

Despite the research that documents poor health outcomes among African American residents living in racially segregated neighborhoods, the research on the association between racial residential segregation and physical activity remains limited and inconclusive. A study conducted by Lopez et al. (2006) found that racial residential segregation was negatively associated with physical activity, while Corral et al. (2012) found a nonsignificant relationship between segregation and physical activity. Incorporating conceptual models may be useful to subjectively and objectively investigate how living in racially segregated areas influences the physical activity of African Americans 50 years and older.

Concept of Therapeutic Landscapes

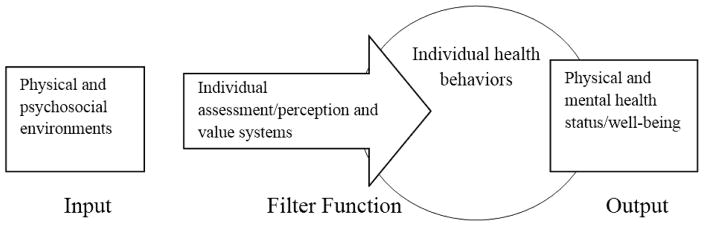

The concept of therapeutic landscapes, which describes places that are associated with treatment or healing and health promotion, can be used to elucidate the role of neighborhood and its effect on health (Braubach, 2007; Gesler, 1992). Braubach (2007) asserts that five characteristics exist within urban neighborhoods that create a therapeutic landscape for health promotion: (1) physical characteristics of the environment; (2) the conditions and functionality of environmental settings; (3) services provided to support the daily life of residents; (4) sociocultural features of neighborhoods; and (5) neighborhood reputation. As seen in Figure 1, an individual’s health status is impacted by a process that starts at the individual’s physical and psychosocial environment and is then filtered through how the individual perceives and ascribes meaning to this environment. For this study, the authors have adapted Braubach’s model to include health behaviors that occur as a result of these processes which then have the potential to contribute to health outcomes and overall well-being (Braubach, 2007). It is theorized that individuals’ participation in physical activity will be determined by how they perceive their environment and in turn influence their overall well-being.

Figure 1.

Model of place effects on health adapted to include health behaviors. Adapted from Braubach, M. (2007). Preventative applications of the therapeutic landscapes concept in urban residential settings: A quantitative application. In A. Williams (Ed.), Therapeutic landscapes (pp. 111–132). Burlington: Ashgate Publishing.

Purpose

Utilizing the concept of therapeutic landscapes, combined with the place stratification model, the purpose of this study was to: (1) examine the association between racial residential segregation and self-reported physical activity, and (2) use the filter function, as proposed by Braubach (2007), to explore the perspectives of older African Americans living in segregated neighborhoods. The authors hypothesized that higher levels of racial residential segregation would be associated with lower levels of physical activity. This study used a mixed methods approach to investigate the intersection between perceived and objective measures of neighborhood influences on physical activity of older African Americans.

Methods

A cross-sectional study design was used to test hypothesized associations between racial residential segregation and physical activity. Secondary data analyses were conducted using North Carolina (NC) data from the Action in Churches in Time to Save Lives (ACTS) of Wellness project. To further understand the quantitative findings, a qualitative analysis was done with a subset of the ACTS participants. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Parent Study Sample and Baseline Data Collection

Quantitative

The ACTS study design was a cluster-randomized controlled trial developed to promote colorectal cancer screening and physical activity within urban African American churches. Church members were eligible to participate if they: (a) were aged 50 and over and (b) a member of the study church. Recruitment of churches occurred from May 2007 to August 2009, yielding a total of 12 churches and 616 church members drawn from three urban areas of NC. Baseline data collected for the ACTS study included demographic information, health information, self-rated health status, self-reported physical activity, and participant home address.

Using the baseline data from ACTS, participants’ home addresses were geocoded using ArcMap (Esri, Redlands, CA). Census 2000 data were used to assess neighborhood-level variables including racial composition, which was used to assess the degree of racial residential segregation, education, and poverty level of each neighborhood at the census tract level, which served as the proxy for neighborhood.

Independent Variable

Racial residential segregation was measured as a continuous variable and was calculated by taking the percent of non-Hispanic African Americans living in the neighborhood. Neighborhoods that were predominantly African American (i.e., a census tract with 50% or more African American residents) were considered racially segregated neighborhoods (Sallis, Kraft, & Linton, 2002; Williams & Collins, 2001). The racial residential segregation variable in the current study ranged in value from 0–80% African American in a census tract.

Dependent Variables

Physical activity was self-reported using a previously validated instrument for the WATCH study, an instrument that was validated by comparing the WATCH measure against the Seven-Day Physical Activity Recall (Campbell et al., 2004; Sallis et al., 1985). This instrument assessed moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic recreational physical activity by using seven preselected activities (run/jog, bike, active sports, dance, swim, walk/hike, and aerobics) and an “other” question where participants could self-report activity. The literature has emphasized that participation in moderate to vigorous physical activity contributes to the reduction of certain types of cancers. Since the ACTS study focused on colorectal cancer, the current study focused solely on moderate to vigorous physical activity (Kushi et al., 2006).

Ainsworth and colleagues’ (1993) compendium of physical activities was used to decide on a case-by-case basis whether to consider the self-reported activity moderate to vigorous intensity (MET value > 3). For each activity selected, participants indicated frequency of participation within the past 30 days, with response options of: rarely/never, 1–3 times/month, 1–2 times/week, 3–4 times a week, or 5 or more times a week. In addition, participants reported their activity duration as less than 20 min (estimated as 15 min) or 20 or more minutes (estimated as 20 min).

Minutes of physical activity and the metabolic equivalent task (MET) hours were used to assess physical activity participation. One MET is equivalent to the amount of oxygen (energy) the average person consumes while seated and resting (Campbell et al., 2004). MET hours/week were computed based on frequency, duration, and a MET (intensity) value (Ainsworth et al., 1993). Physical activity was also dichotomized based on whether participants met the physical activity recommendation of 150 min per week of moderate or vigorous activity (Garber et al., 2011; Elsawy & Higgins, 2010). Four variables were used to describe participants’ level of physical activity, including MET hours per week, minutes of physical activity per week, minutes of walking per week, and meeting physical activity recommendations.

Control Variables

Variables were included in the models that could potentially confound the association between racial residential segregation and physical activity. Male served as the reference category for sex. Age was categorized as 50–60, 61–70 (reference group), 71–80, and greater than 80. Education was categorized as less than high school, high school, college, and post college (reference group). Individual income was categorized into low income (< $10,000–$29,999), middle income ($30,000–$69,999) (reference group), and high income (> $70,000). Marital status was categorized as single, married (reference group), and widowed. Neighborhood poverty was obtained from Census 2000 data and measured as the percent of residents that lived below the poverty line, defined as a family of four with an annual household income of less than $17,050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Neighborhood education, from Census 2000 data, was measured as the number of residents that had more than a high school diploma.

Qualitative

Given the historical context of racial residential segregation, African Americans 50 years and older may have a greater connection and place different meaning on the role of their neighborhood in their lives, overall well-being, and health as compared with their younger counterparts and European American counterparts. As such, an exploratory study was conducted to gain a deeper understanding for the role of racial residential segregation in the lives of African Americans 50 years and older. Using a social constructivist perspective, this study sought to understand and interpret how the meaning of neighborhood and physical activity in this population was shaped by their life experiences and socioeconomic, cultural, and political factors (Kim, 2001).

Purposive sampling was used in the selection of the study participants, who had completed the baseline and follow-up survey for the ACTS study in NC. The follow-up survey included a question that asked if participants would be willing to answer additional questions. This yielded 200 participants. Census tract data were used to determine which participants from this subsample lived in predominantly African American neighborhoods, which yielded 112 participants. Researchers also sought to have a representative sample from each of the three study regions. Sampling was continued until point of data saturation was reached (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006).

Participants were recruited through phone calls made to their home or work place. To be eligible for the qualitative study the person: (a) could not have any physical restrictions that prevented them from being physically active, and (b) had to be willing to devote at least an hour of their time to complete the interview. Once the participant agreed to be interviewed, a study fact sheet was mailed to their address that outlined the purpose of the study and informed them of a monetary incentive upon completion of the interview.

The first author conducted semistructured interviews via the phone from May to July 2011. This method was chosen to reduce the burden on the participant and to maintain consistency in data collection. It has been documented that data obtained from phone interviews can be an adequate substitute for face-to-face interviews when contact has already been made with participants and rapport established (Carr & Worth, 2001; Sturges & Hanrahan, 2004). This was the case in this study, because the first author had previous involvement with the participants during her work with the ACTS intervention. Verbal informed consent was acquired over the phone before the initiation of the interview.

Interview questions focused on the perception of the neighborhood’s influence on participants’ physical activity. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by experienced transcriptionists. Participants were mailed a $30 Visa gift card upon completion of the interview. This incentive was deemed appropriate given the fact that participation in this study involved minimal risk (Grant & Sugarman, 2004). The approximate duration of each call was between 45–240 min.

Quantitative Data Analysis

The analysis examined the association between racial residential segregation and physical activity. Multilevel regression analyses were conducted using Mplus version 6.1 (Los Angeles, CA; Baron & Kenny, 1986). Models were run using the following four physical activity outcomes: minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week, minutes of walking per week, MET hours per week, and a dichotomized variable for meeting physical activity recommendations. The models examined the association of racial residential segregation to each physical activity measure controlling for demographic variables. Data were clustered at the census tract level and were modeled as such in the analyses. To control for the clustering effects of the church, churches were treated as fixed effects. Logistic regression models were used to test the association between racial residential segregation and meeting physical activity recommendations. Because racial residential segregation may be associated with the limited availability of physical activity resources (e.g., recreational facilities, parks, and others), additional analyses were conducted to examine these resources as potential mediators between racial residential segregation and physical activity. Results from these analyses were not significant and therefore are not reported.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Content analysis was used to gain deeper knowledge and understanding of how older African Americans living in predominantly African American neighborhoods gave meaning to their residential context and its role in influencing their health, specifically physical activity (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). A directed content analysis approach was employed because the concept of therapeutic landscapes as outlined by Braubach is limited in its description of a health-promoting neighborhood, and this type of analysis allows for further exploration beyond an a priori set of codes (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Zhang & Wildemuth, 2009). All transcribed data were organized and managed using ATLAS.ti version 6.2 (Corvallis, OR) qualitative text analysis software.

The purpose of coding was to reveal patterns in the text related to understandings, perceptions, actions, and social constructions of the racial residential context and its potentially therapeutic characteristics as described by participants. In addition, coding looked for patterns related to neighborhood characteristics that could possibly describe the association between racial residential segregation and physical activity. This process, which was managed using a codebook, involved identifying segments of the text that provided a description of what people were doing, why they acted in the manner in which they did, and how they were thinking about the way they acted (Warren & Karner, 2010).

Trustworthiness of the findings was established through inter rater reliability, which was accomplished through consultation with a doctoral candidate who checked the coding scheme against 17% percent of the transcripts, which allowed for a critical assessment of interpretations from the direct quotes (Krefting, 1991).

Results

The descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. The final data set consisted of questionnaire responses from 472 participants, of whom 68% were women, 60% were married, and 65% were over the age of 60. Approximately 46% of the sample had at least a college degree, with 45% reporting an annual household income of at least $50,000. The mean proportion of African American residents in a participant’s census tract was 46.4%, ranging from 1.1% to 80.0%. Approximately 34% of participants met the physical activity recommendations. The mean METs value was 8.4 and the mean number of minutes of physical activity was 114, 55 of which were devoted to walking.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Total Participants

|

|

|---|---|

| N = 472 | |

| Female (%) | 68 |

| Mean age (SD) | 65 (8.4) |

| Age groups (%) | |

| 50–60 | 34.1 |

| 61–70 | 41.5 |

| 71–80 | 18.9 |

| > 81 | 5.5 |

| Marital status(%) | |

| Married | 60.2 |

| Single/divorced | 23.5 |

| Widowed | 16.3 |

| Education level (%) | |

| Less than high school | 6 |

| High school | 48 |

| College | 21 |

| Post College | 25 |

| Income (%) | |

| Low income | 30 |

| Middle income | 43 |

| High income | 27 |

| People meeting physical activity recommendations (%) | 34 |

| Mean MET hours/week (SD) | 8.4 (8.6) |

| Mean minutes of physical activity (SD) per week | 114.6 (114.1) |

| Mean minutes of walking (SD) per week | 55.7 (54.9) |

| Mean neighborhood African American composition (SD) | 46.4 (30) |

| Mean neighborhood poverty (SD) | 12.1 (8.8) |

| Mean neighborhood education (SD) | 17.9 (10.3) |

Note. MET = metabolic equivalent task.

Factors Associated With Physical Activity

The results (see Table 2) show that a greater proportion of African American residents in the participant’s neighborhood were associated with 0.56 (p < .05) greater METs. Participants who reported either fair or good health had significantly lower METs than participants who reported an excellent health status. Greater proportions of African American residents in a neighborhood were associated with approximately 9.2 more minutes of physical activity (β = 9.17, p < .01). Participants who reported either fair (β = −27.25, p < .05) or good health (β = −37.81, p < .05) had significantly fewer minutes of physical activity than participants who reported an excellent health status. There was a significant negative association between minutes of physical activity and neighborhood poverty (β = −1.91, p < .05). Lower levels of neighborhood poverty were associated with significantly more minutes of physical activity.

Table 2.

Adjusted Multilevel Regression Models of Measures of Physical Activity

| MET Hours/week | Minutes of PA Per Week | Meet PA Guidelines | Walking Per Week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β | β | OR | β | |

| Racial residential segregation | −.52 | 8.39* | 1.21** | 3.57* |

| Female | ||||

| Male | 1.38 | 10.79 | .93 | 4.15 |

| Age 61–70 | ||||

| Age 50–60 | −.66 | −7.73 | 1.01 | −2.95 |

| Age 70–80 | 1.57 | 3.98 | .98 | −1.41 |

| Age > 80 | −.65 | −20.43 | .65 | −13.98 |

| Middle income | ||||

| Low income | −.51 | −6.05 | .71 | −1.14 |

| High income | 1.88 | 14.74 | 1.36 | 4.7 |

| Post graduate | ||||

| Less than high school | −.59 | 1.36 | 1.3 | 7.8 |

| High school | 1.1 | 3.02 | 1.11 | −4.88 |

| College | .1 | −.2 | .87 | −9.31 |

| Married | ||||

| Single | −.93 | −14.86 | .74 | −5.63 |

| Widow | −.66 | −17.47 | 1.08 | −9.78 |

| Excellent health | ||||

| Fair health | −3.5** | −39.29* | .7 | −16.47 |

| Good health | −2.26 | −28.18* | .62* | −8.02 |

| Neighborhood poverty (%) | −.06 | −1.32 | .97 | −.833 |

| Neighborhood education (%) | −.11 | −1.1 | .97 | −.12 |

Note. MET = metabolic equivalent task; PA = physical activity; OR = odds ratio.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Reference group in italics.

Participants living in more predominantly African American neighborhoods had 1.22 (p < .01) higher odds of meeting physical activity recommendations than those living in more predominantly European American neighborhoods. Minutes of walking were significantly associated with a greater proportion of African American residents in a neighborhood (β = 3.61, p < .05).

In sum, these findings indicated that living in a neighborhood with a greater proportion of African American residents was associated with higher levels of physical activity and increased odds of meeting physical activity recommendations. These findings were contrary to the proposed hypothesis. The results from the quantitative findings helped to inform the direction of the qualitative interviews to further explore possible explanation for the higher rates of physical activity reported by older African Americans living in predominantly African American neighborhoods.

Qualitative

The final qualitative sample size included 12 participants (9 women and 3 men) residing in three different urban areas of NC. Their characteristics are provided in Table 3. The results presented reflect the themes that emerged related to the concept of therapeutic landscapes (Table 4). The narrative of the results represents a synthesis of the findings and relationships that exist within the themes. Results are presented first by examining how people view their neighborhood and then by how their perception of their neighborhood translates into physical activity behaviors.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Interview Participants (N = 12)

| ID | Sex | Age | BMI | Length of Residence | Minutes of Physical Activity Per Week | Minutes of Walking Per Week | MET Hours Per Week | Meet Physical Activity Recommendations (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 75 | 26 | 38 | 45 | 0 | 4.5 | N |

| 2 | F | 65 | 32 | 30 | 150 | 75 | 10 | Y |

| 3 | F | 59 | 43 | 59 | 15 | 15 | .9 | N |

| 4 | F | 66 | 39 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N |

| 5 | M | 65 | 32 | 10 | 255 | 150 | 16.6 | Y |

| 6 | F | 61 | 34 | 23 | 180 | 52.5 | 19 | Y |

| 7 | F | 74 | 30 | 30 | 472.5 | 150 | 31.2 | Y |

| 8 | F | 71 | 20 | 15 | 180 | 150 | 11.2 | Y |

| 9 | F | 62 | 32 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N |

| 10 | F | 62 | 35 | 50 | 165 | 15 | .9 | N |

| 11 | F | 65 | 26 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 2.1 | N |

| 12 | M | 56 | 25 | 25 | 270 | 150 | 20.6 | Y |

Note. BMI = body mass index; MET = metabolic equivalent task.

Table 4.

Major Themes Related to the Model of Place Effects on Health

| Domains | Themes |

|---|---|

| Physical and social characteristics of neighborhood |

|

| Filter function and well-being |

|

Neighborhood Characteristics

Neighborhood Opportunities for Physical Activity

Facilities that were mentioned as spaces for physical activity included the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), community recreational centers, and churches located within 6–8 miles or 10–15 min from participants’ homes. A couple of the participants mentioned community centers close to their homes that offered exercise classes for older people. One participant remarked that her neighborhood lacked nature trails, bike trails, and sidewalks, and had a community center that lacked exercise equipment. She further stated that her neighborhood community center was in disrepair as compared with other community centers located in adjacent, predominantly European American neighborhoods. “In a lot of community centers they have exercise equipment and stuff on a large scale. Some of the centers have swimming. They don’t have that here. So the centers are more geared towards healthy living than this one” (female, 65).

Aging in the Neighborhood

When asked to describe their neighborhood, participants highlighted the age composition of their neighborhood. They were conscious of their age in relation to that of their neighbors, as many of them had been residing in their neighborhood for approximately 30 years and had seen neighbors come and go. “My neighborhood is a diverse neighborhood, we have young people, we have children, and we have middle-aged people, which I consider myself one. We have older people” (female, 62). The diversity in age among residents in certain neighborhoods posed various benefits and challenges to the participants. Some participants were pleased to have younger people in their neighborhood because they contributed to the upkeep of the neighborhood. “People who have kids in the neighborhood are going to take better care of the neighborhood. People don’t want a lot of riff raff around their family and kids” (male, 65).

In contrast, some participants believed that some of the younger people detracted from their neighborhood by loitering in neighborhood stores, playing their music too loud, being disrespectful to elders, and having disregard for property that they did not own. “I’m older and too many young folks, as we say, hanging out, just standing outside. It was just, you know, you’re trying to get in the store and they’re out there standing around talking and in your way” (female, 59).

Neighborhood Racial Identity

In addition to the age of their neighbors, participants also had an awareness of the race of their neighbors. “Well we live in a neighborhood in [city] that is predominantly Black – in fact it’s about 95% Black. It’s a neighborhood that started out White years ago” (female, 71). Within this awareness of neighborhood race, participants also expressed the historical context that the racial makeup of their neighborhood had played for them throughout their lives. In the past, living in a predominantly Black neighborhood represented for them a place of cultural acceptance, solidarity, and connectedness:

“The reason I moved here was because I wanted my children to grow up in a neighborhood where they could look out the door and see professional people doing things, who looked like them… … if they needed something they should be able to ask for it. I didn’t want any racial problems” (female, 65).

These perceptions of their neighborhood illustrate the value that they placed on living in a predominantly African American neighborhood in a historical context and how this value still resonated with them today:

“From a Black perspective, it’s like this is the only history part that I’ve ever known that back in the day the Blacks had, for when people came to [city] they would go to [neighborhood] park for picnics and things like that. That’s where we came together … It seems like they’re not trying to preserve any Black history” (female, 59).

It is important to note that one participant described his neighborhood as a mixed neighborhood, although it was 79% African American. He stated that living in a mixed neighborhood afforded him with access to better resources as opposed to living in a segregated community:

“My neighborhood that I’m living in at the present time is a mixed neighborhood. I came up in a segregated neighborhood. Sometimes things like streetlights went out and it would be a while before they replaced the streetlights. I have a great neighborhood and it’s a lot better than it was before because what I mean by that by being a mixed neighborhood you can get things done a lot better, a lot quicker” (male, 65).

The following themes address participants’ perception of how their neighborhood facilitates and/or inhibits their physical activity.

Neighborhood Physical Features Affect Physical Activity

Participants that lived in close proximity to parks, restaurants, stores, and other resources were able to incorporate physical activity with greater ease. “It’s good for exercise. We walk our dogs, things like that. Sometimes when you’re out you don’t want to drive everywhere. There’s a park right down the street from the house. We go into the park and we walk” (male, 65).

Age of Neighbors as a Factor Influencing Physical Activity

Participants were aware of how their own aging and the aging of their neighbors influenced the dynamics in the neighborhood. One participant believed that the presence of younger people could have the potential to create opportunities for physical activity. “Maybe if I was in a neighborhood with a lot of young couples… … we did a lot of things together like walking and going to the gym. But I haven’t been in the neighborhood with that camaraderie” (female, 65). This notion of young people in the neighborhood having an influence on physical activity was conveyed by another participant who was motivated to keep up with the activities of his younger neighbors:

“Most of the people in the neighborhood do things … You see them walking, running, stuff like that. And everybody, you know, try to be healthy. They’re younger people then we are and they try to keep theirs [exercise] so we try to keep ours too” (male, 65).

Knowing Your Neighbors

Knowing and being known by your neighbors was an important theme that emerged from the interviews. A majority of participants had lived in their neighborhood for over 30 years with the same neighbors and felt that they could depend on their neighbors to alert them of any problems in the neighborhood. Being familiar with their neighbors encouraged them to walk in the neighborhood. Although participants stated that they did not frequent their neighbors’ homes, the sense of familiarity from knowing their neighbors was welcoming:

“Most of the people I know and they know me because all my neighbors now, even if they don’t know me on the newer end, they say, ‘Oh, you’re out doing your walking this morning.’ I feel very comfortable there because they know me” (female, 74).

When asked how their neighborhood influences their physical activity, one participant remarked:

“It’s [neighborhood] pleasant to walk through. It’s not a new neighborhood, but it’s pleasant. I know that when I get out there I’m going to see or speak to somebody. So I don’t really mind getting out there and walking because of that” (female, 66).

Embedded within this theme of knowing their neighbors, many participants specifically discussed the experience of living in a predominantly African American neighborhood, and how this facilitated physical activity. Participants associated living in a predominantly African American neighborhood with trust, camaraderie, and mutual respect:

“It’s a Black community. You know the people, you know the neighborhood, they’re friendly, and they look out for each other. We were like that; people would walk in the neighborhood mornings and evenings. It was laid back, a quiet Black neighborhood” (male, 56).

Feeling of Safety

The feeling of safety was described mainly by the women interviewed in terms of the physical aspects of the neighborhood along with the social environment. Some avoided walking during the morning rush hours when high traffic was a safety concern. Another participant highlighted how safety issues in her neighborhood had changed over time, which influenced her willingness to walk. “I used to walk a lot in the neighborhood and then I stopped when the neighborhood changed with the gangs and that. So I started to walk again because the neighborhood has changed back to a more peaceful area” (female, 62). Similar to the theme of knowing your neighbors, living in a predominantly African American neighborhood influenced participants’ feelings of safety. Some of the participants expressed that they felt safe living in a predominantly African American neighborhood because they felt a sense of belonging. One participant illustrated this in the quote below:

“I felt totally accepted in my neighborhood, it was an all-Black neighborhood; I was totally safe. There were a group of us; we did everything together. We played together… we went to Sunday school and church together. It was a safe environment…” (female, 65).

Other characteristics of a predominantly African American neighborhood mentioned by participants that contributed to their feeling of safety included togetherness, tight-knit community, and people looking out for each other.

Discussion

Few studies have been conducted that examine variables associated with both racial residential segregation and physical activity among older African Americans. None to our knowledge have been conducted in the United States’ South. This study found that for older African Americans, living in racially segregated, urban neighborhoods of NC was associated with higher levels of physical activity and increased odds of meeting physical activity recommendations.

These findings were inconsistent with those of other studies that have found no effect between racial residential segregation and physical activity (Corral et al., 2012; Lopez, 2006). The other studies used a single-item measure of physical activity in the past month (Corral et al., 2012; Lopez, 2006). In contrast, this study used four different physical activity variables, derived from the number of minutes of seven different types of exercises per week in the last 30 days. Moreover, this study extended previous research with the addition of qualitative interviews with a subset of the study sample to explore how older African Americans who live in racially segregated neighborhoods perceived and placed meaning on their surroundings and how this contributed to their physical activity.

The findings from the qualitative interviews (e.g., their feelings of comfort, safety, and acceptance from living in racially segregated neighborhoods) may explain why physical activity was higher among participants with a higher percentage of African Americans in their neighborhoods. Perceived safety, acceptance, and comfort from knowing one’s neighbors are concepts that relate to social cohesion.

Studies have found that communities with high levels of social cohesion have community members that report good health (Kawachi, Subramanian, & Kim, 2008; Kawachi & Berkman, 2000). A study examining neighborhood influences on physical activity among a mixed racial sample of older adults found that social cohesion was associated with higher levels of neighborhood walking, despite safety and neighborhood problems (Fisher et al., 2004). The social cohesion that the current study’s interviewees expressed as being present in their neighborhood describes positive aspects of racially segregated neighborhoods that are often omitted from studies on health and racial residential segregation. (Landrine & Corral, 2009). Understanding more about the mechanisms by which racial residential segregation impacts health is essential to determine how best to address health concerns of residents living in these neighborhoods.

In addition, findings from this study do not support those from previous studies, which have documented the association between access to physical activity resources and actual engagement in physical activity (Heinrich et al., 2008; Hoehner, Brennan Ramirez, Elliott, Handy, & Brownson, 2005; Humpel, Owen, & Leslie, 2002). One explanation may be in how potential moderators are conceptualized and measured. For example, this study’s qualitative findings revealed that although resources for physical activity were in close proximity to their place of residence, they were not necessarily used, due to quality, time constraints, and individual accountability. Underutilization of physical activity resources have also been identified in other studies conducted among urban African American women and a predominantly rural European American population (Maley, Warren, & Devine, 2010). Future research needs to explore more specifically the moderating effects of individual and environmental determinants of physical activity among older African Americans who do have access to physical activity resources.

At the same time, this study had some methodological limitations that should be considered when interpreting the nonsignificant association between access to physical activity resources and actual physical activity. This study did not examine street connectivity, presence of sidewalks, or crime, all of which have been linked to walking in older adults (Michael, Perdue, Orwoll, Stefanick, & Marshall, 2010). In addition, asking participants to report the name, location, and proximity to residence of the physical activity facilities they used could have strengthened this study. This study was cross-sectional in nature, so causality could not be determined. In addition, the sampling frame was not necessarily representative of all older African Americans because these participants were drawn from churches. All physical activity measures were self-reported and therefore subject to recall biases, where participants may be unable to accurately recall past events (Coughlin, 1990). In addition, self-reported data are also subject to social desirability, where participants provide responses that present them in a positive light (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Notwithstanding, every effort was made to reduce the presence of biases by providing specific response options regarding physical activity and through confidential data collection.

Nonetheless, this study’s strengths can be found in the use of the concept of therapeutic landscapes and the place stratification model, which informed the conceptual model. The concept of therapeutic landscapes informed the qualitative component of this study by exploring how participants perceived their neighborhood environment and in turn how this contributed to their physical activity. Braubach’s model of place effects on health posits that neighborhood resources and characteristics can impact an individual’s health outcomes depending on how the individual perceives or filters these factors (Braubach, 2007). Understanding this filtering process was achieved in this study with the use of the semistructured interviews. The interviewees were very aware of the characteristics of their neighborhood, specifically identifying how the racial composition of their neighborhood influenced their life and their health. Most participants viewed the predominantly African American composition as a positive aspect of their neighborhood that contributed to a sense of comfort and security, which translated into health promoting behaviors such as walking. The place effects model can be employed in other studies to discover how individuals perceive their neighborhood’s influence on their health.

Another strength of this study is the application of a mixed method mode of inquiry. The use of mixed methods in this study offered a set of tools to collect and analyze various forms of data that could be synthesized to provide a plausible association between living in racially segregated neighborhoods and being physically active that was found among participants.

Conclusions

This study revealed that the intersection of health and place for older African Americans is multifaceted, especially for those living in predominantly African American neighborhoods. These facets include, physical, social, historical, and individual. The way in which some older African Americans place meaning on their neighborhood environment may differ from the meaning that someone else places on the same environmental feature, thus segregation does not have the same meaning for everyone. Barriers for one population may be perceived as assets to another population. Researchers should account for this in their study of neighborhood access and health behaviors.

Racial residential segregation, which is viewed by many as deleterious to health, was also described in a positive manner by those living in these neighborhoods, primarily because of their perceptions of their neighborhood. Racial residential segregation is socially constructed (Gotham, 2000). As such, understanding its influence on health requires incorporating a social perspective that transcends the measures of neighborhood racial composition and examines the experiences of people residing in these areas. Building upon this study, future intervention research should examine ways to enhance or create social cohesion in these communities through such activities as intergenerational gatherings, having community projects to plant trees, forming neighborhood walking groups, and engaging community members to feel empowered to make changes in their community centers or neighborhoods to promote healthy living. One way to achieve this is through the creation of residential block associations that are focused on collective beneficial goals for the neighborhood such as more streetlights or the beautification of the neighborhood. These associations may have the effect of fostering norms of trust and feelings of safety and connectedness (Mendes de Leon et al., 2009). In addition, out of these associations residents could form exercise groups with shared exercise goals that build cohesion through social support (Estabrooks & Carron, 1999). This could also allow for intergenerational interactions among the younger and older residents.

The emphasis that participants placed on knowing their neighbors highlights the importance of the neighborhood social environment. The historical context of the neighborhood is another facet of place and health relevant for older African Americans. For many of these people, their neighborhood once represented a place of solace in a time of turmoil. These shared experiences connect them to their neighborhood and to their neighbors. Many of the current therapeutic effects of the neighborhood described by the interview participants were a function of their experiences accumulated over an extended period of time spent in the neighborhood. These findings show that what is commonly referred to in the literature as “geographic clustering” or “racial residential segregation” can be redefined as the density of values, beliefs, and similarities, which can enhance and support positive health outcomes. Thus, the results from the current study help us to alter existing stereotypes and conceptualizations, and redefine what we measure as segregation and its associated health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the significant contributions of Dr. Marci K. Campbell, who was a professor in the Department of Nutrition at UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. In addition, the authors would like to thank Dr. Sonya Armstrong and Amanda Henley for their consultant work. The authors are grateful for all the participants, especially the interviewees, for devoting their time to this research. This research was supported by a grant award to UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Pre-doctoral Traineeship, Grant No. R25CA57726 and partially supported by a grant award to the UNC Institute on Aging by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) PostDoctoral Traineeship, Grant No. 5T32AG000272

Contributor Information

Janelle Armstrong-Brown, Institute on Aging, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Eugenia Eng, Gillings School of Global Public Health, Health Behavior, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Wizdom Powell Hammond, Gillings School of Global Public Health, Health Behavior, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Catherine Zimmer, Howard W. Odum Institute for Research in Social Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

J. Michael Bowling, Gillings School of Global Public Health, Health Behavior, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Lochner KA, Osypuk TL, Subramanian SV. Future directions in residential segregation and health research: A multilevel approach. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):215–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, Paffenbarger RS. Compendium of physical activities: Classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1993;25(1):71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba RD, Logan JR. Minority proximity to whites in suburbs: An individual-level analysis of segregation. American Journal of Sociology. 1993;98(6):1388–1427. doi: 10.1086/230193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell JF, Zimmerman FJ, Almgren GR, Mayer JD, Huebner CE. Birth outcomes among urban African American women: A multilevel analysis of the role of racial residential segregation. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(12):3030–3045. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond Huie SA. The components of density and the dimensions of residential segregation. Population Research and Policy Review. 2000;19(6):505–524. doi: 10.1023/A:1010611901602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp M, Lattimore D, Wilcox S, Laken M, McClorin L, Swinton R, … Bryant D. Understanding physical activity participation in members of an African American church: A qualitative study. Health Education Research. 2007;22(6):815–826. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp M, Wilcox S, Laken M, Butler K, Carter RE, McClorin L, … Yancey A. Factors associated with physical activity among African-American men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(4):340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braubach M. Preventative applications of the therapeutic landscapes concept in urban residential settings: A quantitative application. In: Williams A, editor. Therapeutic landscapes. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing; 2007. pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, James A, Hudson MA, Carr C, Jackson E, Oates V, … Tessaro I. Improving multiple behaviors for colorectal cancer prevention among African American church members. Health Psychology. 2004;23:492–502. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr ECJ, Worth A. The use of the telephone interview for research. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2001;6(1):511–524. doi: 10.1177/136140960100600107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corral I, Landrine H, Hao Y, Zhao L, Mellerson JL, Cooper DL. Residential segregation, health behavior and overweight/obesity among a national sample of African American adults. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17(3):371–378. doi: 10.1177/1359105311417191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1990;43(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes de Leon CF, Cagney KA, Bienias JL, Barnes LL, Skarupski KA, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Neighborhood social cohesion and disorder in relation to walking in community-dwelling older adults A multilevel analysis. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21(1):155–171. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsawy B, Higgins KE. Physical activity guidelines for older adults. American Family Physician. 2010;81(1):55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks PA, Carron AV. Group cohesion in older adult exercisers: Prediction and intervention effects. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1999;22(6):575–588. doi: 10.1023/A:1018741712755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KJ, Li F, Michael Y, Cleveland M. Neighborhood-level influences on physical activity among older adults: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2004;12(1):45–63. doi: 10.1123/japa.12.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flippen CA. Residential segregation and minority home ownership. Social Science Research. 2001;30(3):337–362. doi: 10.1006/ssre.2001.0701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman L. Minority housing segregation: A test of three perspectives. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2000;22(1):15–35. doi: 10.1111/0735-2166.00037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Singer A, Price M, Cheung I. Race, immigrants, and residence: A new racial geography of Washington, DC. Geographical Review- New York- 2005;95(2):210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher NA, Gretebeck KA, Robinson JC, Torres ER, Murphy SL, Martyn KK. Neighborhood factors relevant for walking in older, urban, african american adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2010;18(1):99–115. doi: 10.1123/japa.18.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin B, Lamonte MJ, Lee I, … Swain DP. American college of sports medicine position stand. quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2011;43(7):1334–1359. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesler WM. Therapeutic landscapes: Medical issues in light of the new cultural geography. Social Science & Medicine. 1992;34(7):735–746. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham KF. Urban space, restrictive covenants and the origins of racial residential segregation in a US city, 1900-50. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2000;24(3):616–633. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RW, Sugarman J. Ethics in human subjects research: Do incentives matter? The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 2004;29(6):717–738. doi: 10.1080/03605310490883046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich KM, Lee RE, Regan GR, Reese-Smith JY, Howard HH, Haddock CK, … Ahluwalia JS. How does the built environment relate to body mass index and obesity prevalence among public housing residents. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2008;22(3):187–194. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehner CM, Brennan Ramirez LK, Elliott MB, Handy SL, Brownson RC. Perceived and objective environmental measures and physical activity among urban adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(2):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humpel N, Owen N, Leslie E. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(3):188–199. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iceland J, Wilkes R. Does socioeconomic status matter? race, class, and residential segregation. Social Problems. 2006;53(2):248–273. doi: 10.1525/sp.2006.53.2.248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen S, Nazroo JY. Relation between racial discrimination, social class, and health among ethnic minority groups. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):624–631. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.4.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. Oxford, Oxford: University Press; 2000. pp. 174–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D. Social Capital and Health. In: Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D, editors. Social Capital and Health. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. Social constructivism. Orey M, editor. Emerging Perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. 2001 retrieved January 24, 2014 from: http://www.coe.uga.edu/epltt/SocialConstructivism.htm.

- Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991;45(3):214–222. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, Gansler T, … Thun MJ. American cancer society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: Reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2006;56(5):254–281. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.5.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwarteng JL, Schulz AJ, Mentz GB, Zenk SN, Opperman AA. Associations between observed neighborhood characteristics and physical activity: Findings from a multiethnic urban community. Journal of Public Health. 2014;36(3):358–367. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Corral I. Separate and unequal: Residential segregation and black health disparities. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19(2):179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA. Racial segregation and longevity among African Americans: An individual-level analysis. Health Services Research. 2003;38(6 Pt 2):1719–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez R. Black-white residential segregation and physical activity. Ethnicity & Disease. 2006;16(2):495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maley M, Warren BS, Devine CM. Perceptions of the environment for eating and exercise in a rural community. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2010;42(3):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Denton NA. American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Gross AB, Shibuya K. Migration, segregation, and the geographic concentration of poverty. American Sociological Review. 1994;59(3):425–445. doi: 10.2307/2095942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michael YL, Perdue LA, Orwoll ES, Stefanick ML, Marshall LM. Physical activity resources and changes in walking in a cohort of older men. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(4):654–660. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC, … Sceppa C. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American college of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2007;39(8):1435–1445. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616aa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KE, Martin LM, Chowdhury PP. Places to walk: Convenience and regular physical activity. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(9):1519–1521. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert SA, Ruel E. Racial segregation and health disparities between black and white older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61(4):S203–S211. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.S203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Blair SN, Paffenbarger RS. Physical activity assessment methodology in the five-city project. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1985;121(1):91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Kraft K, Linton LS. How the environment shapes physical activity A transdisciplinary research agenda. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(3):208–215. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satcher D. Our commitment to eliminate racial and ethnic health disparities. Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics. 2001;1(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: The impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61(4):212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturges JE, Hanrahan KJ. Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: A research note. Qualitative Research. 2004;4(1):107–118. doi: 10.1177/1468794104041110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Poverty Thresholds 2000 [Web site] 2000 Available: https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/threshld/thresh00.html.

- Warren CAB, Karner TX. Discovering qualitative methods: Field research, interviews, and analysis. Los Angeles: Roxbury Publishing Company; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/Ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wildemuth BM. Qualitative analysis of content. In: Wildemuth B, editor. Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library. Portland: Book News; 2009. pp. 308–319. [Google Scholar]