Abstract

Aim:

To present the methods and outcomes of stakeholder engagement in the development of interventions for children presenting to the emergency department (ED) for uncontrolled asthma.

Methods:

We engaged stakeholders (caregivers, physicians, nurses, administrators) from six EDs in a three-phase process to: define design requirements; prototype and refine; and evaluate.

Results:

Interviews among 28 stakeholders yielded themes regarding in-home asthma management practices and ED discharge experiences. Quantitative and qualitative evaluation showed strong preference for the new discharge tool over current tools.

Conclusion:

Engaging end-users in contextual inquiry resulted in CAPE (CHICAGO Action Plan after ED discharge), a new stakeholder-balanced discharge tool, which is being tested in a multicenter comparative effectiveness trial.

Keywords: : asthma, health communication, patient discharge, pediatrics, stakeholder engagement, written action plan

Comparative effectiveness research is intended to address the expressed needs of patients, caregivers and other decision-makers in healthcare [1]. Such engagement is considered critical to evaluating interventions relevant to end-users and that are feasible for use in real world clinical settings. National and international asthma guidelines recommend the use of written instructions to promote appropriate use of medications, avoidance of environmental triggers and advice about when to seek additional medical attention [2,3]. However, systematic reviews indicate that the content, format and benefits of such written instructions (usually called action plans) are highly variable, with relatively low rates of use because most action plans are designed by teams of medical experts with relatively little input from patients, caregivers and clinicians [4,5].

The CHICAGO study is a multicenter comparative effectiveness trial funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) to test strategies to improve the care and outcomes of African–American and Latino children with uncontrolled asthma presenting to the emergency department (ED) in Chicago [6]. In Chicago, African–American and Latino children aged 5–11 years bear a disproportionate share of the burden from asthma [7]. Among the most visible of these disparities is the five- to seven-fold higher rate of visits to the ED for uncontrolled asthma in communities with a high proportion of African–American and Latino children compared with other communities [department of public health, chicago, pers. commun]. As part of the PCORI-funded CHICAGO study, we employed user-centered design methods to engage caregivers, clinicians and administrators in the development and evaluation of an asthma discharge tool for African–American and Latino children who present to the ED for uncontrolled asthma [8]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of methods and outcomes of end-user engagement to develop an asthma discharge tool tailored to high-risk children for a comparative effectiveness trial. We are now testing the effectiveness of the asthma discharge tool on implementation and clinical outcomes in the multicenter CHICAGO pragmatic clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02319967) [9].

Methods

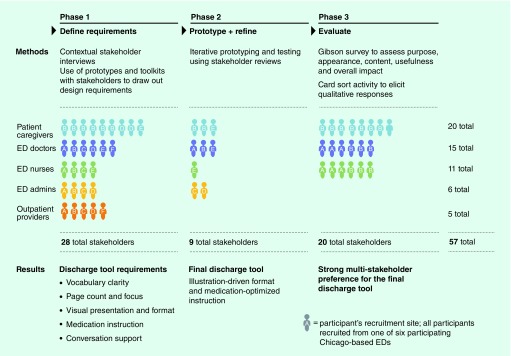

We engaged four stakeholder groups: caregivers of minority children with a history of uncontrolled asthma presenting to the ED in the past 12 months; ED physicians and nurses; ED administrators; and outpatient clinicians. Stakeholders from six EDs in Chicago that would serve as the centers for the clinical trial (CHICAGO ED clinical centers) were engaged in a three-phase process that employed various methods of contextual inquiry (Figure 1): define design requirements with multistakeholder user input; prototype and refine to shape a discharge tool that fits the content and support needs of all key stakeholders; and evaluate end-user stakeholder preferences for the new and existing discharge tools. The study was approved by institutional review boards (IRBs) at all participating institutions, IRB #2014-0412, 2014-056, 2014-15829, MSH #14-10, 14-0534, 14-095 and 13083001-IRB01 at the University of Illinois at Chicago (IL, USA), Illinois Institute of Technology (IL, USA), Lurie Children's Hospital (IL, USA), Mount Sinai Hospital (IL, USA), University of Chicago Medicine (IL, USA), Cook County Hospital (IL, USA) and Rush University Medical Center (IL, USA), respectively.

Figure 1. . We employed a three-phase design process to develop a stakeholder-balanced asthma discharge tool.

Stakeholders included patient caregivers, emergency department clinicians (physicians, nurses, administrators) and ambulatory (outpatient) physicians. A highlight of findings from each stage is also presented.

ED: Emergency department.

A convenience sample of physician and nonphysician clinicians and administrators from each of the participating six ED clinical centers participated as key informants. Key informants were selected to be representative of their clinical center in their ability to speak to the processes and materials involved in discharge from the ED and as active end-users on the clinical side. Similarly, a convenience sample of caregivers of black or Hispanic/Latino children who had visited at least one of the six ED clinical centers in the past 12 months participated in focus groups, user-centered home observations or both. Previous studies have established the critical role of triggers in the home environment and inadequate asthma controller use as risk factors for asthma exacerbations and emergency department visits in children with asthma. Thus, the asthma discharge tool included a focus on both environmental control and appropriate use of asthma medications [10–14].

Phase I: define design requirements

Data collection in Phase I employed a user-centered design approach that combines field interviews conducted onsite in a user's home or workplace with direct observation of users engaged in relevant tasks. These methods come from the field of design, which are not typically used in qualitative health research. The primary difference is that design employs a contextual approach that focuses on context of use – not just a tool or its content – and conducts the inquiry using user-centered observations. [15]. Central to contextual inquiry is the belief that human actions can only properly be understood in context, and that all activity is informed by immediate circumstances and therefore is best observed ‘in the wild’ rather than in a lab or through recounting past events with others in focus groups [16]. We, therefore, conducted all inquiry in clinical settings in the ED and ambulatory sites, and in the homes of caregivers. We also employed projectives, which in this study were prototype discharge documents, toolkits from which physicians could construct their own discharge document and probes consisting of stakeholder-drawn visualizations of relevant past and present experiences of asthma management and ED experiences (Figure 2).

Figure 2. . Sample projectives used with stakeholders in Phase I (from left to right): a caregiver-drawn asthma journey map; a physician-annotated prototype discharge tool; three sample discharge tools built by outpatient providers from a toolkit of preprinted sticky notes.

We conducted 19 key informant stakeholder interviews with physicians, nurses and administrators from the ED, and outpatient clinicians. All interviews were conducted in the ED or ambulatory setting for 60–80 min. Two interviewers were present, and interviews were audio-recorded and photographed. The key informant protocol covered three domains: ED patient discharge experience using open-ended questions, discharge simulations and role play to target challenges and barriers in preparing a patient/caregiver for discharge; asthma treatment recommendations on ED discharge, including barriers to implementing these components in their ED or practice; and prototype discharge tool review to elicit feedback about preferred discharge instructions.

We also conducted interviews with caregivers of African–American and Latino children with a history of an ED visit for uncontrolled asthma in the past 12 months in one or more of the CHICAGO ED clinical centers. Eight of the caregivers were African–American and one was Latino, seven were single mothers, seven had other children and seven had other family members diagnosed with asthma. All interviews were conducted in the home and ranged from 2 to 3 h. They were audio-recorded and transcribed. A digital camera was used to document the home environment and location of relevant artifacts, such as storage of medications and discharge documents. Interviews targeted baseline asthma knowledge, self-management practices and recent ED discharge experience across four touchpoints – waiting, triage, treatment and discharge. The approach consisted of open-ended questions, review of a prototype discharge document and use of multiple probes and activities to help caregivers express asthma care experiences.

All interview data were coded and analyzed using principles of Grounded Theory to identify recurring patterns of beliefs, interactions, behaviors and needs across stakeholder groups and clustered into design requirements and opportunity areas for concept development [17,18]. Analysts worked in pairs to ensure intercoder reliability (S Norell, J Rivera and T Flippin).

Phase II: prototype & refine

A total of 9 caregivers, ED clinicians (physicians and nurses) and ED administrators were engaged in two iterations of assessment and refinement to converge on a single discharge tool that incorporated health literacy and information design principles (maximum Flesch–Kincaid 6th reading grade level; reduced word count, sentence length, text blocks and medical jargon; consistent use of typographic hierarchy and underlying grid; and key information presented in illustration and callouts) [19–24]. We also evaluated the Flesch–Kincaid reading level of existing discharge documents at the CHICAGO ED clinical centers. The CHICAGO investigators (clinicians, social scientists, community health workers and supervisors) then collaborated in providing feedback to the design team to finalize an asthma discharge tool for use in children presenting to the ED with uncontrolled asthma.

Phase III: evaluate stakeholder preferences

We then assessed preferences among caregivers and ED clinicians by comparing the documents currently in use in two different CHICAGO ED clinical centers with the newly developed tool. We employed a published quantitative assessment tool (Gibson survey) that evaluates five domains (purpose, appearance, usefulness, overall impact and for clinicians, content) developed for patients/caregivers (15 items) and clinicians (30 items) [25]. Participants were asked to respond using a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree); possible scores are 1–5, with higher scores indicating greater preference. To understand the rationale for preferences among caregivers and clinicians, we also employed qualitative methods using a card sorting activity. Card sorting works to surface mental models and evaluate participant agreement by providing a stack of cards containing phrases or words and asking each participant to sort the cards into categories, as makes sense to them [26,27]. A total of 11 cards were presented to clinicians, with another 11 to caregivers. All cards were crafted with first-person statements, such as “I think this document provides more guidance for my patients after discharge” and were structured to capture both participant behaviors and attitudes. Responses were tabulated and assessed for patterns across and within stakeholder segments using data visualization software Nineteen [28].

Results

Phase I: define design requirements

We conducted 28 on-site stakeholder interviews with nine caregivers, six ED physicians, four ED nurses, four ED administrators and five outpatient clinicians (Figure 1). Analysis of contextual research data produced eight themes for in-home asthma management practices and three themes related to ED discharge experiences (Table 1).

Table 1. . Themes from contextual research in the home and emergency department sites.

| Themes | Details | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tools to share information, coordinate care | Need to educate others Need to share information |

“(You need to) not only educate yourself, but to educate others that you will leave your child with for long periods – babysitters, caregivers, teachers” – Caregiver “Maybe (we could have) a website to get this action care plan to print out and give to the school or caretaker? Something that you can educate somebody with in 2 min?” – Caregiver |

| 2. Discharge information stored out of sight | Need for simplified instruction Stored, not displayed Repetitive information ignored |

“I keep them in a bin where I keep all my mail and stuff. Then after a year or two, I go through it, and what ever needs to be thrown out, I throw out” – Caregiver “It is pretty much duplicates of what we have. So I have it piled up. I have a ton of stuff to shred now” – Caregiver |

| 3. Learning through trial and error causes gaps in understanding in even experienced caregivers | Mental model of asthma pieced together through trial and error, personal experience Logic of asthma hard to see, plan for Well-intended actions often ineffective |

“I hope she does not catch (an asthma attack) today because it is raining at one point, then it is hot at another point” – Caregiver “Every time he has had an asthma attack, it has been different situations. So we do not really know what his trigger is. The initial time it was fresh cut grass that set him off. It has been a change of temperature, it has been if you spray something, if he has been around somebody with a cold. And so it is very hard to say, okay, what triggered it this time?” – Caregiver “Germs are a trigger … so I clean. I bleach. I am a bleach fanatic” – Caregiver |

| 4. Medication workarounds | Inhalers do not last as long as they should Families share inhalers Substitute with ‘rescue’ medicine – inhalers need to travel |

“If my son uses up the inhaler within 2 or 3 weeks, what am I supposed to do for the other week? Because you have 4 weeks in the month” – Caregiver “My mom is an asthmatic, so we will go to her house and get some asthma spray (when ours runs out)” – Caregiver “If we are out, I have no choice but to use the rescue inhaler” – Caregiver “I have visits where …they are bringing the babysitter and the grandma and the dad and the mom. And they are trying to figure out how they are going to transfer the kids’ medications between all these sites”– Outpatient provider |

| 5. Medication confusion | Inhaler mix-ups Medication names sound alike ‘Better = cured’ |

“Fast acting or rescue medication? Honestly? I never knew what the controller medicine was to what is a rescue medicine” – Caregiver “This Proventil sounds like preventative. So I might have said take Flovent, the orange pump…and the patient comes back with a yellow and orange Proventil pump and says yeah, this is the prevent one. I take two puffs every morning and two puffs every night. I am like no! I can not even tell you how many times that has happened” – Outpatient provider “When they first sent him home with the medication I was like I am not giving him all that medication all the time, he does not need it” – Caregiver |

| 6. Patient education positioned at the weakest moment in discharge | Caregiver fatigue Repetitive information Neglecting other family |

“Parents do not want to sit here and listen to this stuff when their ride is waiting outside and they have already been here for 4–6 h, and they are tired and hungry and miserable and their kid is screaming”– ED physician “Upon discharge, they give you the whole work-up – discharge instructions, a number to call for emergencies, follow-up appointments, information on asthma. They do it every time. Even if we are so used to the information we do not need it any more” – Caregiver “4 h is the most we have stayed there. I am just ready to go, because of the other three (kids) I have at home” – Caregiver |

| 7. Fragmented discharge process | ‘Treat and street’ Discharge distributed across staff Staff hand-off allows information to slip through the cracks |

“Normally, the nurse will come back…with the prescriptions and further instructions. First the doctor always comes in and says whatever, then the nurse is the one who comes back and gives you your discharge” – Caregiver “Multiple professionals could be responsible for (discharge), you know, so when multiple people could be involved, if each of those people is mediocre, you could get discharged with paperwork that says nothing” – ED nurse |

| 8. Clinician, caregiver conversations not well-supported by tools | Tools are dense, text-heavy, hard to use Conversation is the educational touchpoint |

“Most of the time I do not pay very much attention to the discharge paper because it offers me nothing. I can not imagine that it offers much to the patient” – ED nurse “It gets to be 15 pages…you hand this to them and they are like, ‘What is all this stuff?’ If there is something important, I try to circle it” – ED physician “We do not have good education tools, and everything falls back to the nurse at the end of the line” – ED nurse “The value in a discharge document…is the teaching that happens when you are giving the document. The document should be a teaching tool, not only ‘the thing you receive” – Outpatient provider |

ED: Emergency department.

Tools to share information, coordinate care

Caregivers expressed the need for a discharge tool that facilitates communication, education and coordination of care with others (babysitters, extended family, school, daycare and camp personnel) who share in the care of their children.

Discharge information stored out of sight

Current discharge documents are often stored in bags, drawers and with stacks of bills, so are not easily available for reference if needed. No caregivers had asthma-related information on display in the home.

Learning through trial & error causes gaps in understanding even in experienced caregivers

The sheer number of contributing factors can make the logic of asthma exacerbations hard to piece together. While our caregivers reported prioritizing their children's health – by moving, leaving their jobs, delaying promotions to be more available to care for their children, vigorous cleaning or keeping kids inside – interviews suggested their management strategies are often based on an incomplete understanding of asthma. The resulting failure of proactive efforts can promote reactive behavior (i.e., ED visits).

Medication workarounds

Medication adherence is tough even for informed caregivers. Inhalers run out, causing families to share or to substitute reliever medicine. Because childcare usually occurs outside the home, shared inhalers must travel to multiple sites and return home without getting lost.

Medication confusion

Many caregivers and outpatient clinicians reported confusion between reliever and controller inhalers. Caregivers also expressed distrust of continuous steroid use and potential side effects on their growing child, affecting their commitment to prescribed regimens.

Patient education positioned at the weakest moment

Discharge protocols position patient education at the moment when patient caregivers are least prepared to take advantage of it – in the last 20 min of a typically 3–6 h (or longer) ED visit. Several nurses expressed frustration with caregivers’ unwillingness or inability to focus on patient education at discharge. Caregivers also reported frustration related to lengthy discharge processes, repetition of information they say they already know, and the need to manage work, other children and household obligations reduces receptivity to education at discharge.

Fragmented discharge experience

Operational realities can produce an ED discharge experience that is executed piecemeal and by multiple staff members. For example, sometimes the attending physician delivers medication instruction, a resident attempts patient education and a nurse prints and delivers paperwork. This workflow may change based on the number of patients waiting to be seen or acuity of illness among patients in the ED – the pressure to ‘treat and street’ was noted as a driver of practice variation. Clinical staff reported that continuity and predictability in discharge is difficult to provide using hand-offs, especially in EDs where poor site lines can limit communication between staff.

Clinician/caregiver conversations not well-supported by existing tools

Caregivers often receive large amounts of information at an ED visit. Clinic staff across sites reported numerous challenges in communicating that information to caregivers in the ED. Many staff said they do not review discharge documents with patients, as time is tight and documents are long, complicated and hard to use with caregivers.

Stakeholder input regarding the design of the discharge tool identified several design priorities for the discharge tool (Table 2).

Table 2. . Design requirements.

| Requirements | Details | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Vocabulary clarity + reading level | Simplify language and sentence structure Use layman's terms, not medical jargon |

“A lot of our patients cannot read, and their parents cannot read, and then you hand them an asthma action plan and do the best that you can” – ED doctor “In the beginning, you are not familiar with the medical terms, so you kind of have to … explain it just a little simpler” – Caregiver “I see things that confuse my patients. For example, many do not know what an MDI is, so call it something that they are going to understand”– ED nurse |

| 2. Page count + focus | Reduce word count Promote action steps Remove extraneous material |

“There are so many pages that nobody looks at any of them…” – ED physician “The paperwork that EDs give now comes from the EMR, so it is filled with great nuggets but there is totally unnecessary blather. When patients look at it, they cannot find the things they actually need” – Outpatient provider “They give you all these sheets, and to be quite honest, as a parent, just tell me what is going on. Tell me what I need to do. I am not going to take time – although my son is sick, do not get me wrong – but I am not taking time to read through all your literature. Just get to the plan of action here” – Caregiver |

| 3. Visual presentation + format | Engage kids in care Earn a spot on the refrigerator Use visuals so as to include everyone Make easy to copy and share |

“I need to explain to him about asthma and the tightening of the chest and all of that, because he needs to know … so that one day if I am not there, he can say it himself” – Caregiver “It has one thing to educate caregivers, which is important, but in the end, it has got to be the child. The child is going to know when he cannot breathe” – ED nurse “I would definitely put something (visual) on the front page so that the kid knows ‘it is mine” – ED admin nurse “All patients have different learning styles, right? You might not be able to assess that fully in an emergency encounter. But you could hit on multiple areas. For example, use written education from the asthma plan and visual cues that patients can identify” – Outpatient provider |

| 4. Medication instruction | Clearly organize medication types Clarify timing, duration and dosages Reinforce medication adherence as priority |

“The means of administering medications, how to use them, when to use them is very confusing. All the medications have two different names. Many of them come in multiple different forms. They may be given two different asthma pumps, and I think they do not know the difference or they may be asked to use equipment that they have no familiarity with, like a spacer or a nebulizer machine, or for that matter even be exposed to medication forms that they are not familiar with” – Outpatient provider |

| 5. Conversation support | Standardize key messages Simplify discharge conversation Provide a shared tool to anchor the conversation Help caregivers participate Help caregivers share with others in their care circle |

“Give me the simplest protocol I can remember while running from room to room” – ED physician “I think the nurses themselves do not understand what they need to communicate to the patient, thinking that they (patients) would just know” – ED admin nurse “I would say most of the time I talk a lot and when I am done I always ask if they have got questions and I do not get much” – ED nurse “(If they bring this document) I would know that at least the education has started. It would help me here, too, because sometimes many show up without any paper work, and I have got 15 min to figure out what happened” – Outpatient provider |

ED: Emergency department.

Vocabulary clarity + reading level

Reduce complexity and simplify language to include children, more caregivers and others outside the family.

Page count & focus

Remove extraneous content and streamline to focus on caregiver action steps.

Visual presentation & format

Use illustrations and layout to make key ideas accessible and inclusive, while retaining a professional and serious appearance.

Medication instruction

Organize, clarify and detail all medication-related instruction so as to create a plan that caregivers can understand and follow.

Conversation support

Simplify and structure the protocol for clinicians, support discussion of sensitive topics and make a tool caregivers can use with others.

Phase II: prototype & refine

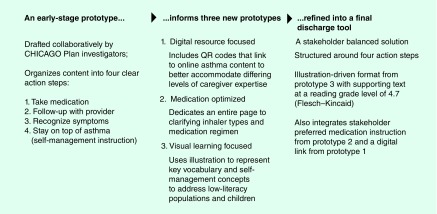

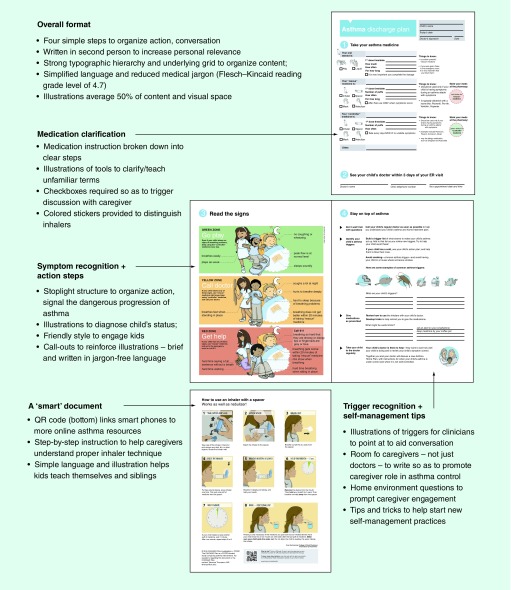

Nine stakeholders participated in prototype reviews (three caregivers; three ED physicians; one ED nurse and two ED administrators, Figure 1). In these reviews, stakeholders were presented with three potential discharge tool concepts based on Phase I results and were asked to engage in two cycles of review and collaborative editing (Figures 2 & 3). Across stakeholder groups, highly-illustrated visual learning concepts earned the strongest favorable responses for its simplicity, clarity, visual appeal and ease of use. Literacy levels of patients and caregivers were a recurring topic in the formative research. Many ED physicians asked for solutions that used visual strategies to offset the complexity of text. ED nurses sought tools that could engage children directly in self-management. Caregivers also expressed confusion and impatience with materials that were hard to read, apply and share. In response, we customized illustrations to explain key vocabulary and self-management concepts and employed the traffic light construct of green/yellow/red zones to aid caregiver assessment. The final CHICAGO asthma discharge tool, called the CAPE (CHICAGO Action Plan after ED discharge) (Figure 4), has a Flesch–Kincaid reading level of 4.7 (compared with existing documents in use across the CHICAGO ED clinical centers that had reading levels of 5.5–7.8). The final discharge tool is also designed to support simplified reading strategies by using multiple principles of information design, such as typographic hierarchy to create priority and aid browsing, use of an underlying grid and white space to reduce visual complexity, reduced line length and text blocks to increase readability and the option for printing or copying in black and white for low-cost distribution.

Figure 3. . In Phase II, an early prototype was refined through iterative stakeholder input to develop a new discharge tool, CAPE (CHICAGO Action Plan after emergency department discharge).

CHICAGO: Coordinated Healthcare Interventions for Childhood Asthma Gaps in Outcome; QR: Quick response.

Figure 4. . The new discharge tool, or CAPE (CHICAGO Action Plan after emergency discharge), includes several key advances in design to improve communication of medications, symptom recognition and action steps, and trigger recognition and self-management.

CHICAGO: Coordinated Healthcare Interventions for Childhood Asthma Gaps in Outcome; QR: Quick response.

Phase III: evaluate stakeholder preferences

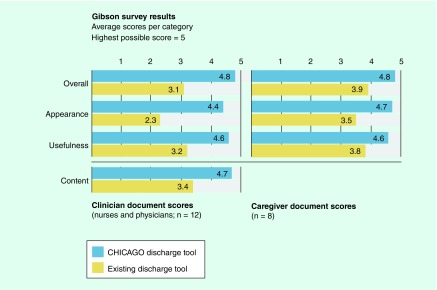

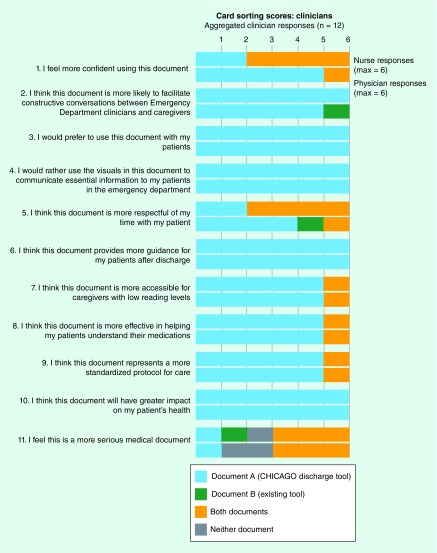

Results of the Gibson survey suggested caregiver and clinician preference for the new discharge tool across all categories (Figure 5). Qualitative assessments using the card sorting activity also demonstrated a preference for the new discharge tool (Figure 6). Among clinicians, the card sorting activity elicited strong emotional responses as they shared their frustrations over their current asthma action plans. There was full consensus for the new tool for four of eleven questions (items 3, 4, 6 and 10). Clinicians reported that they favored the new tool in part because of its clarity; one physician observed that “for our patient population, this is awesome…it is not too dense, and it is not word overloaded. This is very succinct. It is easy to understand.” Clinicians also indicated that the new tool could serve as a support for conversations and for teaching self-management. One clinician noted that the new tool was ‘more interactive, so as you go through it people will have a visual and can ask questions’, whereas when using the existing document ‘there is not as much to go through, step-wise, so its less likely that you are going to be able to point and continue a dialog based on what is in the document’.

Figure 5. . Using the Gibson survey, clinicians and caregivers report higher levels of preference for the new discharge tool, CAPE (CHICAGO Action Plan after ED discharge), compared with existing documents.

CHICAGO: Coordinated Healthcare Interventions for Childhood Asthma Gaps in Outcome.

Figure 6. . The card sorting activity supports findings from the Gibson survey, indicating greater clinician preference for the new discharge tool, CAPE (CHICAGO Action Plan after emergency department discharge).

CHICAGO: Coordinated Healthcare Interventions for Childhood Asthma Gaps in Outcome.

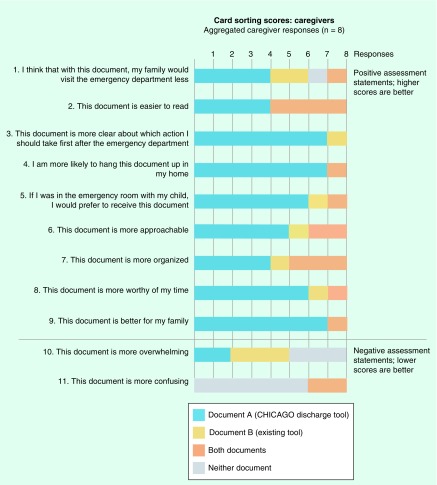

Caregiver responses also demonstrated a preference for the new discharge tool (Figure 7). However, caregiver responses were strongest for the new tool when queried about behavioral items, such as “This document is more clear about which actions I should take after the Emergency Department” (item 3) or “I am more likely to hang this up in my home” (item 4) or “I would prefer to receive this document in the emergency room” (item 5). Overall document preference was more equivocal when statements raised issues that could be interpreted as relating to their competency, such as “This document is harder to read” or “This document is more confusing.” The research team also encountered differences in language use, with one participant, for example, selecting the new tool as ‘more overwhelming’, as in overwhelmingly good. Such responses raise important issues about the wording of questions to fit target populations.

Figure 7. . The card sorting activity supports findings from the Gibson survey, indicating greater caregiver preference for the new discharge tool.

CHICAGO: Coordinated Healthcare Interventions for Childhood Asthma Gaps in Outcome.

Discussion

In this report, we presented the methods and outcomes of a three-phase process that employed various methods of contextual inquiry in the design of CAPE, a novel stakeholder-balanced asthma action plan for high-risk African–American and Latino children with uncontrolled asthma for use on ED discharge. Several aspects of CAPE are noteworthy, including the use of a design that maximizes visual learning and individualization. More important than the final tool, however, is the process employed to create it. The formative process presented here demonstrates a new multistakeholder driven methodology to inform the development of interventions suitable for comparative effectiveness research. This method is novel because it shifts the design process from one that relies exclusively on teams of medical experts who focus on content to multidisciplinary teams with expertise in uncovering the context of use to inform content requirements, which may also help to overcome barriers to implementation in real-world clinical and nonclinical settings. Contextual inquiry differs from standard qualitative inquiry because it is designed to immerse the investigator in the everyday practices of the informant, rather than asking the informant to recall their experiences, as standard interview or focus group methods do. With informants and investigators both working in situ, informants reveal with their behavior what they often fail to recall when asked, and investigators build firsthand experience with how informants engage in the activity being studied. For the CAPE, as an example, contextual inquiry revealed that complex conversations between stakeholders were taking place unsupported by existing materials. Designing for conversation guided content development and format. We are now testing the effectiveness of the asthma discharge tool on implementation and clinical outcomes in the multicenter PCORI-funded CHICAGO comparative effectiveness trial.

Comparative effectiveness research is intended to be a response to the expressed needs of end-users about which interventions are most effective for patients under specific circumstances [1]. To our knowledge, this is the first report to engage end-users in contextual inquiry in designing asthma action tools for children, their caregivers and clinicians providing medical care in EDs. Contextual inquiry is an important addition to comparative effectiveness research because it creates a new form of evidence. By locating the research team in the context of use, data is collected not just about patient practices, but how those practices are shaped by interactions with others, how practices become embedded (or not) in everyday activities and responsibilities and how practices are negotiated against the inevitable disruptors of everyday life that compete for patients’ time and attention. This evidence is especially productive when seeking to tailor interventions to populations and circumstances for better uptake and adherence. Additionally, contextual inquiry is equally productive when applied to ED clinical staff, who report struggling with tools and protocols that do not seem designed to fit the complex operational realities of the ED and its many users. Indeed, results of quantitative and qualitative assessments suggest substantial preference among clinical staff for the new tool's ease of use and fit with desired caregiver conversations, compared with existing tools used in the ED.

By design, our new discharge tool shifts the communication paradigm in the ED from delivery of information (from expert to novice) to supporting collaborative conversation (between equally engaged stakeholders). This is an important shift because it institutionalizes what some clinicians in this study have already acknowledged: that communication is more effective when built with caregivers through an exchange of information in the moment than ‘delivered’ to them in a monologue or handout. The new discharge tool was noted by clinical staff as a tool that ‘at least starts the conversation’, ‘opens up the conversation better’ and ‘is more interactive as you go through it with people’. Shifting to a collaborative model in the ED also creates new conditions that encourage caregivers to see themselves as partners in asthma control. Current ED experiences contribute to caregiver belief that an asthma attack is an event best fixed by a doctor in an ED; a collaborative approach can stress asthma as a chronic condition best managed by caregivers at home.

While our project offers multiple strengths, our approach to engagement was limited to addressing the needs of elementary school-age high-risk African–American and Latino children with uncontrolled asthma presenting to the ED. This focus was deliberately given the goals of our PCORI-funded CHICAGO comparative effectiveness trial. However, the discharge tool may not be sufficiently optimized for other populations (e.g., preschoolers, adolescents, adults). While we did include physicians and nurses, our engagement process did not include other clinicians who provide care to children with uncontrolled asthma (e.g., respiratory therapists, social workers, pharmacists). Moreover, most of our children and their caregivers were low income and African–American. The methods employed in this project offer a template for future work that could address the needs of other end-user populations, including those with other conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, sickle cell disease).

Conclusion

We present the application of contextual inquiry of end-user stakeholders to design a novel ED-based asthma action plan (CAPE) for a comparative effectiveness trial in asthma. We speculate that engaging multiple stakeholders in the design of a discharge tool ‘fit for purpose’ offers a promising approach for improving asthma self-management skills and improving asthma outcomes in African–American and Latino children presenting to the ED for uncontrolled asthma. Our on-going PCORI-funded CHICAGO comparative effectiveness trial will evaluate the effects of employing CAPE (vs usual care) in the ED on implementation and clinical outcomes.

Executive summary.

Designing interventions to improve communication in comparative effectiveness research

Multistakeholder driven design methods of contextual inquiry can be successfully employed to inform the development of interventions for comparative effectiveness research.

Our approach shifted the design process from one that relies exclusively on teams of medical experts who focus on content to multidisciplinary teams with expertise in uncovering the context of use to inform content requirements, which may also help to overcome barriers to implementation in real-world clinical and nonclinical settings.

The new discharge tool or CAPE (CHICAGO Action Plan after emergency department discharge) shifts the communicationparadigm in the emergency department from delivery of information (from expert to novice) to supporting collaborative conversation (between equally-engaged stakeholders).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of T MacTavish, IIT Institute of Design; JT Senko, JH Stroger, Jr Hospital of Cook County; CJ Lohff, Chicago Department of Public Health; ZE Pittsenbarger, Ann and Robert H Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago; J E Kramer, Rush University Medical Center; H Margellos-Anast, LS Zun, Mount Sinai Hospital; SM Paik and J Solway, University of Chicago; ML Berbaum, N Bracken, and HA Gussin, for their role in the development of the CHICAGO comparative effectiveness trial. The authors thank L Sanker for her help in the development and conduct of focus groups. The authors also thank the families and the staff in the CHICAGO ED clinical centers and partner organizations who contributed their time to make this study possible.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The study was sponsored by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (contract #AS-1307-05420). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

References

- 1.Comparative Effectiveness Research: National Institutes of Health. PCAST Session on Health Reform and CER. 2009. www.whitehouse.gov/files/documents/ostp/PCAST/Nabel%20Presentation.pdf

- 2.National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 3: guidelines on asthma. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/current/asthma-guidelines/full-report

- 3.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) www.ginasthma.org/

- 4.Gupta S, Wan FT, Ducharme FM, Chignell MH, Lougheed MD, Straus SE. Asthma action plans are highly variable and do not conform to best visual design practices. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108(4):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ring N, Jepson R, Hoskins G, et al. Understanding what helps or hinders asthma action plan use: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011;85(2):e131–e143. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. www.pcori.org/research-results/2013/coordinated-healthcare-interventions-childhood-asthma-gaps-outcomes-chicago

- 7.Gupta RS, Zhang X, Sharp LK, Shannon JJ, Weiss KB. Geographic variability in childhood asthma prevalence in Chicago. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;121(3):639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin B, Hanington B. Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas and Design Effective Solutions. Rockport Publishers; MA, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggleston PA, Diette G, Lipsett M, et al. Lessons learned for the study of childhood asthma from the Centers for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(10):1430–1436. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swartz LJ, Callahan KA, Butz AM, et al. Methods and issues in conducting a community-based environmental randomized trial. Environ. Res. 2004;95(2):156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eggleston PA, Butz A, Rand C, et al. Home environmental intervention in inner-city asthma: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95(6):518–524. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Muhsen S, Horanieh N, Dulgom S, et al. Poor asthma education and medication compliance are associated with increased emergency department visits by asthmatic children. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10(2):123–131. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.150735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams RJ, Fuhlbrigge A, Finkelstein JA, et al. Impact of inhaled anti-inflammatory therapy on hospitalization and emergency department visits for children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):706–711. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beyer H, Holtzblatt K. Contextual design. Interactions. 1999;6(1):32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suchman L. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser B, Strauss A. Aldine de Gruyter; NY, USA: 1967. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990;13(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seligman HK, Wallace AS, DeWalt DA, et al. Facilitating behavior change with low-literacy patient education materials. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007;31(0 1):S69–S78. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills (Second Edition) J.B. Lippincott Company; PA, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doak CC, Doak LG, Friedell GH, Meade CD. Improving comprehension for cancer patients with low literacy skills: strategies for clinicians. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 1998;48(3):151–162. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.48.3.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oates DJ, Paasche Orlow MK. Health literacy: communication strategies to improve patient comprehension of cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2009;119(7):1049–1051. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.818468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Kripalani S. Strategies to address low health literacy and numeracy in diabetes. Clin. Diabetes. 2010;28(4):171–175. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Plain language: a promising strategy for clearly communicating health information and improving health literacy. www.health.gov/communication/literacy/plainlanguage/PlainLanguage.htm

- 25.Gibson PA, Ruby C, Craig MD. A health/patient education database for family practice. Bull. Med. Libr. Assoc. 1991;79(4):357–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cataldo EF, Johnson RM, Kellstedt LA, Milbrath LW. Card sorting as a technique for survey interviewing. Pub. Opin. Quart. 1970;34(2):202–215. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nawaz A. The 10th Asia Pacific Conference on Computer Human Interaction (Apchi 2012) Matsue-city, Shimane, Japan: 28–31 August 2012. A comparison of card sorting analysis methods. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erwin K, Pollari T. EPIC: The Ethnographic Practice In Industry Conference. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2013. Small packages for big (qualitative) data; pp. 44–61. [Google Scholar]