Abstract

Objective

To estimate the frequency of MRSA transmission to gowns and gloves worn by healthcare personnel (HCP) interacting with nursing home residents in order to inform infection prevention policies in this setting

Design

Observational study

Setting and Participants

Residents and HCP from 13 community-based nursing homes in Maryland and Michigan

Methods

Residents were cultured for MRSA at the anterior nares and perianal or perineal skin. HCP wore gowns and gloves during usual care activities. At the end of each activity, a research coordinator swabbed the HCP’s gown and gloves.

Results

403 residents were enrolled; 113 were MRSA colonized. Glove contamination was higher than gown contamination (24% vs. 14% of 954 interactions, p<0.01). Transmission varied greatly by type of care from 0% to 24% for gowns and 8% to 37% for gloves. We identified high risk activities (OR >1.0, p< 0.05) including: dressing, transferring, providing hygiene, changing linens and toileting the resident. We identified low risk activities (OR <1.0, p< 0.05) including: giving medications and performing glucose monitoring. Residents with chronic skin breakdown had significantly higher rates of gown and glove contamination.

Conclusions

MRSA transmission from MRSA positive residents to HCP gown and gloves is substantial with high contact activities of daily living conferring the highest risk. These activities do not involve overt contact with body fluids, skin breakdown or mucous membranes suggesting the need to modify current standards of care involving the use of gowns and gloves in this setting.

Introduction

Healthcare personnel (HCP) serve as a vector for MRSA transmission in institutional settings. In acute care hospitals, Contact Precautions (single room, gown and gloves for all patient-healthcare personnel contact, patient room restriction) are used for patients colonized with MRSA to prevent transmission to other patients.1 The usefulness of Contact Precautions for MRSA colonized residents in nursing homes has not been evaluated.2–4 In nursing homes, the emphasis for infection prevention is on the use of Standard Precautions (gowns and gloves for contact with blood, body fluids, skin breakdown or mucous membranes) with all residents.4 Unlike patients in acute care hospitals, residents are encouraged to interact with one another, eat in common areas and share other activities. Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Isolation Guidelines are vague and suggest deciding whether to implement Contact Precautions or to modify Contact Precautions for MRSA colonized residents based on local case-mix,1 largely due to lack of evidence.3

The use of Standard Precautions is limited by the lack of concrete guidelines for when to wear gowns and gloves. Detection of MRSA on HCP gown and gloves during healthcare personnel-patient interactions allows us to study the risk of transmission due to individual types of care.5–7 The overall goal of our research is to determine the optimal use of gowns and gloves in community-based nursing homes. Our primary objective was to estimate the risk of MRSA transmission to gowns and gloves by type of care provided during the interaction. We hypothesized that some activities such as those involving contact with secretions (e.g. draining wounds, ostomy care) will be of higher risk than others (e.g. vital signs, medications). We were also interested in specific resident characteristics such as presence of skin breakdown or stool incontinence and their role in MRSA transmission.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a multi-center, prospective observational study to estimate the frequency of and risk factors for MRSA transmission to gowns and gloves worn by HCP when providing care to nursing home residents. During the study, we had HCP wear gowns and gloves when interacting with enrolled residents. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Maryland Baltimore and University of Michigan.

Population

Residents from 13 non-VA, community-based nursing homes in Maryland and Michigan were enrolled. The nursing homes ranged in size from 62 to 209 beds; four were not-for-profit. Eligible residents had: 1) an expected length of stay of at least one week; 2) to speak English and 3) had to consent or assent or have a lack of dissent to study procedures. Eligible residents were enrolled with written informed consent from them (84%) or their legally authorized representative (16%). HCP were enrolled with verbal consent.

In our primary analysis, we assessed the risk of MRSA transmission when HCP interacted with residents with MRSA colonization based on cultures on enrollment. A resident was defined as MRSA colonized if the anterior nares or perianal skin swabs grew MRSA. We also assessed MRSA transmission rates when care was provided to residents who were not colonized with MRSA on enrollment by selecting a random sample of residents without MRSA colonization and cultured the gown and gloves from care interactions with these residents.

Data Collection

We recorded demographic characteristics, type of long term care (rehabilitation vs. residential care), recent hospitalizations, activities of daily living, case mix index including resource utilization groups (RUG scores), current antibiotic use, skin breakdown, medical devices and uncontrolled secretions from the Minimum Data Set,8 medical records and nursing home staff. A resident was defined as receiving rehabilitative care or residential care based on their resource utilization group.

Cultures were obtained from the residents’ anterior nares and perianal skin using a nylon flocked swab (Copan ESwabs; Copan Diagnostics Inc., Murrieta, CA). HCP were asked to wear gowns and gloves during usual care activities (e.g. wound dressing) up to 28 days after resident enrollment. A research coordinator observed and recorded the type and duration of care delivered with each activity. After the activity, the coordinator swabbed the healthcare personnel’s gown and gloves as described previously.5–7 HCP followed standard infection control practices for gown and glove use during the study. If they needed to change gown or gloves between care activities, cultures were done and a new observation started.

Laboratory Procedures

Specimens from residents, gowns and gloves were cultured for MRSA at a central laboratory. Swabs from residents were vortexed and 50μL of Aimes media placed on CHROMagar Staph aureus (BD, Sparks, Maryland) and streaked to isolation. In addition, 50μL of Amies media was placed in Tyrptic soy broth with 6.5% NaCl and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. After overnight incubation 50μl of broth was plated on CHROMagar Staph aureus. One swab from the double headed swabs used for the gowns and gloves was place into TSB with 5% NaCl and the other was placed in Brain Heart Infusion broth and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. 50μL of each broth was plated separately on CHROMagar Staph aureus. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Mauve-colored colonies on CHROMagar Staph aureus suspicious for S. aureus were confirmed by the detection of coagulase (Staphaurex; Remel, Lenexa, KS). Methicillin resistance was determined by oxacillin screening following CLSI guidelines.9

A convenience sample of 15 MRSA isolates from residents and the 39 corresponding MRSA isolates from gown and glove contamination had molecular typing to assess concordance and to demonstrate that gown and glove contamination was due to transmission from the resident. Each MRSA isolate was typed by DNA sequencing analysis of a single locus, the protein A (spa) gene hypervariable region as previously described.10 Spa typing was used because of concordance with PFGE, its ease of use, reproducibility, and the advantages of unambiguous sequence analysis.11

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

All study data were entered into a centralized relational database. Quality control was performed every 4 months via logic checks on the entirety of the database and comparison of source documentation to the database values for 10% of the participants. The association between MRSA colonization and resident characteristics was measured using the chi square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, the Student t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. All statistical tests were two-tailed and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with Stata 12 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

The risk of MRSA transmission for a particular type of care was estimated using a proportion (e.g. # of glove specimens collected during a specific type of care that grew MRSA/# of glove specimens collected during a specific type of care). Because resident-HCP interactions could include more than one type of care, we compared the risk of MRSA transmission for each type of care when it was given with another type of care to the risk when the type of care was given alone. When the risk of transmission was meaningfully different (the risk went from high to low), we separated the type of care into (a) with other types of care and (b) alone.

Odds ratios (the odds of MRSA transmission given receiving a particular type of care divided by the odds of MRSA transmission given not receiving that care) were estimated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an exchangeable covariance structure. GEE adjusted for more than one observation of a type of care within a resident. Odds ratios significantly greater than 1 were considered high risk types of care and those significantly less than 1, low risk types of care. To determine whether certain resident characteristics increased the risk of transmission for a particular type of care, that variable was included in the model as a potential effect modifier.

Results

Resident Characteristics

Over 25 months, 1,838 residents were screened for enrollment of whom 1,143 were eligible and 403 (35% of eligible) were enrolled. Of the 740 residents that were eligible, but not enrolled, 564 did not consent and 176 the legally authorized representative (LAR) did not give consent for study participation. Two residents withdrew from the study prior to obtaining cultures for a final study population of 401 residents. One hundred thirteen (28%) of 401 residents were colonized with MRSA. Sixty two percent were colonized only in the anterior nares, 9% were colonized only at the perianal skin, and 28% were colonized at both the anterior nares and the perianal skin.

Compared with non-MRSA colonized residents, MRSA colonized residents were more likely to be in residential care and more likely to have: a pressure ulcer, heart failure, chronic lung disease or stroke (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of residents with cultures (n= 401) stratified by MRSA colonization status

| Characteristic | Overall Population N (%) n=401 |

With MRSA Colonization N (%) n=113 |

Without MRSA Colonization N (%) n=288 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 78 ± 11 | 80 ± 10 | 78 ± 12 | 0.22 |

|

| ||||

| Male | 122 (30) | 45 (40) | 77 (27) | 0.01 |

| Female | 279 (70) | 68 (60) | 211 (73) | |

|

| ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.33 | |||

| Asian | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Black or African American | 85 (21) | 28 (25) | 57 (20) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| White | 309 (77) | 83 (73) | 226 (79) | |

|

| ||||

| Nursing Home in | 0.28 | |||

| Maryland | 223 (56) | 58 (51) | 165 (57) | |

| Michigan | 178 (44) | 55 (49) | 123 (43) | |

|

| ||||

| Length of stay in Nursing Home prior to enrollment in days (median, IQR) | 26 (7, 243) | 52 (12, 250) | 21 (6, 221) | 0.07 |

|

| ||||

| Rehabilitation Care | 240 (60) | 56 (50) | 184 (64) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Acute care hospitalization in past 3 months | 252 (63) | 59 (53) | 193 (67) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Activities of Daily Living Score8 (mean ± SD) | 7.8 ± 4.1 | 8.6 ± 4.4 | 7.5 ± 4.0 | 0.03 |

|

| ||||

| Case Mix Index Score8 (median, IQR) | 29 (17, 51) | 23 (12, 47) | 38 (18, 52) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Current antibiotic use at enrollment | 57 (14) | 14 (12) | 43 (15) | 0.50 |

|

| ||||

| Devices | ||||

| Indwelling urinary catheter | 35 (9) | 13 (12) | 22 (8) | 0.23 |

| Feeding tube | 16 (4) | 5 (4) | 11 (4) | 0.78 |

|

| ||||

| Skin breakdown | ||||

| Surgical wound(s) | 76 (19) | 9 (8) | 67 (24) | <0.01 |

| Chronic skin breakdowna | 66 (17) | 24 (21) | 42 (15) | 0.11 |

| Unhealed pressure ulcer(s) ≥ Stage 1 | 58 (15) | 24 (21) | 34 (12) | 0.02 |

| Ostomy | 11 (3) | 6 (5) | 5 (2) | 0.08 |

| Other skin breakdown | 21 (5) | 3 (3) | 18 (6) | 0.21 |

|

| ||||

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| Cancer (with or without metastasis) | 16 (5) | 7 (7) | 9 (4) | 0.16 |

| Coronary artery disease | 81 (23) | 25 (26) | 56 (23) | 0.52 |

| Heart failure | 63 (16) | 25 (22) | 38 (13) | 0.03 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 47 (12) | 19 (17) | 28 (10) | 0.05 |

| Renal insufficiency, renal failure, ESRD | 52 (15) | 16 (17) | 36 (14) | 0.59 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 149 (37) | 50 (44) | 99 (35) | 0.08 |

| Arthritis | 110 (32) | 22 (23) | 88 (35) | 0.03 |

| Stroke | 67 (17) | 26 (23) | 41 (15) | 0.04 |

| Dementia | 76 (20) | 23 (21) | 53 (19) | 0.69 |

| Hemiplegia or hemiparesis | 18 (5) | 6 (5) | 12 (4) | 0.65 |

| Chronic lung disease | 83 (21) | 34 (30) | 49 (17) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Secretions at enrollment | ||||

| Stool incontinence | 59 (15) | 20 (18) | 39 (14) | 0.30 |

| Diarrhea | 10 (3) | 0 (0) | 10 (4) | 0.07 |

| Heavy wound secretions | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Heavy respiratory secretions | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

Chronic skin breakdown is defined as the absence of surgical wound(s) and the presence of at least one of the following: unhealed pressure ulcer(s) ≥ Stage 1, ostomy or other skin breakdown

Gown and Gloves Contamination with MRSA by Type of Care

We observed a median of 7 interactions per MRSA colonized resident (IQR 6–11 interactions), with each interaction lasting a median of 6 minutes (IQR 5–11 minutes). Seventy-three percent of the interactions had one type of care during the interaction; 13%, two; 7% three and 7% four or more. Two types of care were stratified by: a) with other care activities and b) the only care because of substantial differences in the risk of transmission. The risk of MRSA transmission to gowns with giving medications was 18% when with other care and 8% when giving medications was the only care. The risk of MRSA transmission to gowns with monitoring blood glucose was 30% when with other care and 0% when the only care.

Overall, gowns were contaminated with MRSA during 14% of 954 interactions with MRSA colonized residents. Gloves were contaminated during 24% of 954 interactions (p<0.01). Spa typing of MRSA isolates from 15 MRSA colonized residents and 39 MRSA isolates from gowns or gloves showed that 89% were identical with the resident isolate, 8% closely related and the remaining 3% were discordant.

We selected a random sample of 23 residents without MRSA colonization at enrollment and cultured gowns and gloves from care interactions with these residents. Out of the 150 gown swabs tested from these MRSA negative residents, 8 were MRSA+ (5%); out of the 150 glove swabs tested, 8 were MRSA+ (5%). Two of these residents without MRSA colonization at enrollment had three positive gown or glove cultures; 10 residents had a single positive gown or glove culture.

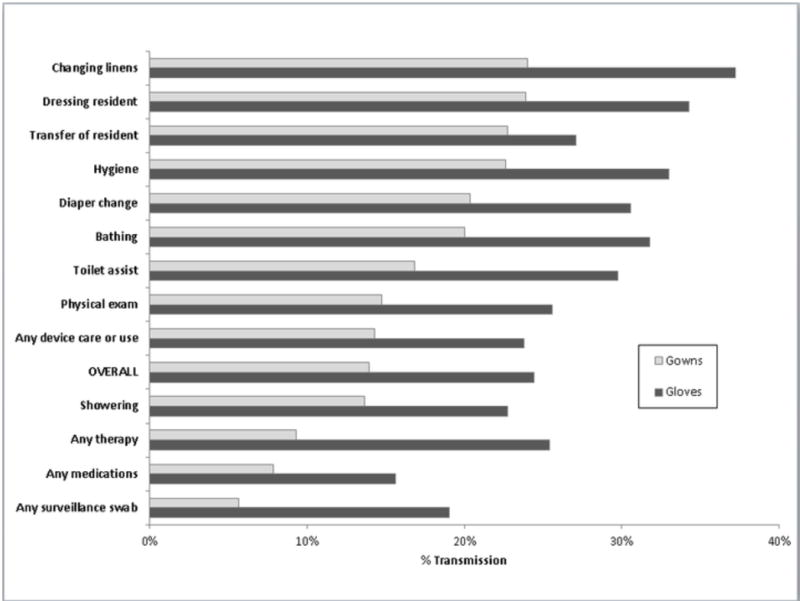

Transmission varied by type of care activity from 0% to 24% for gowns and 8% to 37% for gloves (see Figure 1) demonstrating high and low risk activities. We identified dressing the resident, transferring the resident, providing hygiene (brushing teeth, combing hair), changing linens and changing diapers as high risk activities (OR >1.0, p< 0.05, Table 2). Giving medications and performing glucose monitoring were low risk activities (OR <1.0, p< 0.05, Table 2) when they were the only type of care during the interaction. Multiple interactions with at least one high risk activity were more common compared with low risk care activities which tended to occur as single activities (42% of interactions with at least one high risk activity are bundled as compared to 4% of interactions with all low risk activities, p <0.01).

Figure 1.

MRSA Transmission to Gowns and Gloves of Healthcare Personnel during care of MRSA colonized residents (n=113) by Type of Care provided during 954 interactions

Table 2.

Odds Ratio, Odds of Gown or Glove Contamination given Type of Care over odds of Gown or Glove Contamination if that type of care was not given, adjusted for clustering within individual MRSA colonized residents

| Gown | Glove | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Care | N | % of care which occurred with other types of care | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Dressing | 138 | 91% | 2.33 (1.50, 3.61) | <0.01 | 1.81 (1.33, 2.45) | <0.01 |

| Transfer | 167 | 70% | 2.13 (1.44, 3.13) | <0.01 | 1.25 (0.90, 1.72) | 0.19 |

| Hygiene | 106 | 92% | 1.98 (1.20, 3.28) | <0.01 | 1.58 (1.09, 2.30) | 0.02 |

| Change linens | 129 | 39% | 1.84 (1.19, 2.83) | <0.01 | 1.77 (1.13, 2.78) | 0.01 |

| Diaper | 108 | 81% | 1.66 (1.02, 2.72) | 0.04 | 1.48 (1.05, 2.09) | 0.02 |

| Toilet | 95 | 66% | 1.53 (0.98, 2.40) | 0.06 | 1.26 (0.78, 2.02) | 0.35 |

| Bathing | 85 | 81% | 1.47 (0.85, 2.56) | 0.17 | 1.48 (0.99, 2.21) | 0.06 |

| Any dressing change | 18 | 50% | 1.24 (0.38, 4.02) | 0.72 | 1.08 (0.54, 2.16) | 0.83 |

| Any device care or use | 42 | 48% | 1.17 (0.54, 2.52) | 0.69 | 1.09 (0.59, 2.02) | 0.79 |

| Shower | 22 | 81% | 1.08 (0.35, 3.33) | 0.90 | 1.08 (0.46, 2.54) | 0.87 |

| Physical exam | 129 | 36% | 0.99 (0.59, 1.66) | 0.97 | 0.99 (0.67, 1.47) | 0.97 |

| Glucose monitoring | 21 | 48% | 0.81 (0.20, 3.32) | 0.77 | 0.35 (0.08, 1.50) | 0.16 |

| Any medications | 180 | 22% | 0.70 (0.43, 1.14) | 0.15 | 0.58 (0.36, 0.92) | 0.02 |

| Any therapy | 118 | 19% | 0.67 (0.35, 1.29) | 0.23 | 1.11 (0.74, 1.66) | 0.62 |

| Feeding | 13 | 15% | 0.59 (0.09, 3.93) | 0.58 | 0.36 (0.07, 2.05) | 0.25 |

| Any medications alone | 141 | 0% | 0.50 (0.27, 0.92) | 0.03 | 0.56 (0.33, 0.95) | 0.03 |

| Glucose monitoring alone | 11 | 0% | Did not converge-zero cell | 0.52 (0.11, 2.56) | 0.42 | |

Resident characteristics that increase Gown and Glove Contamination with MRSA

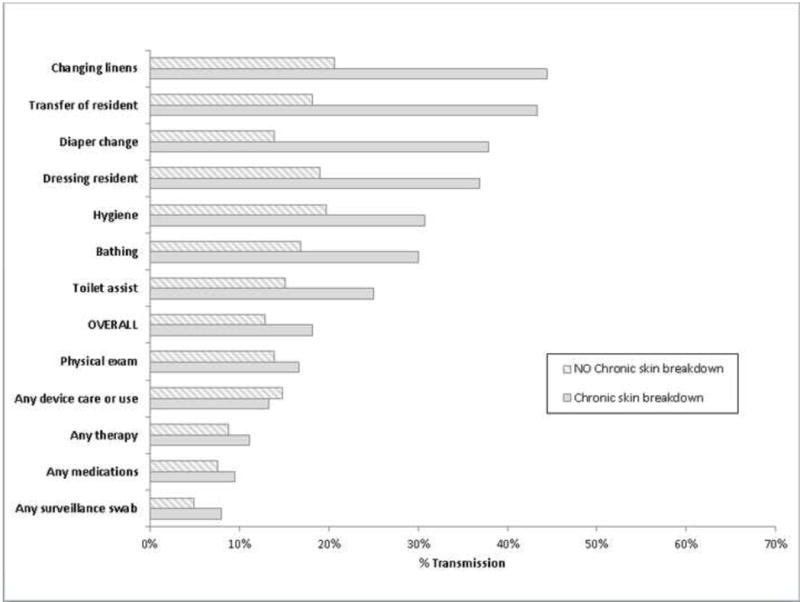

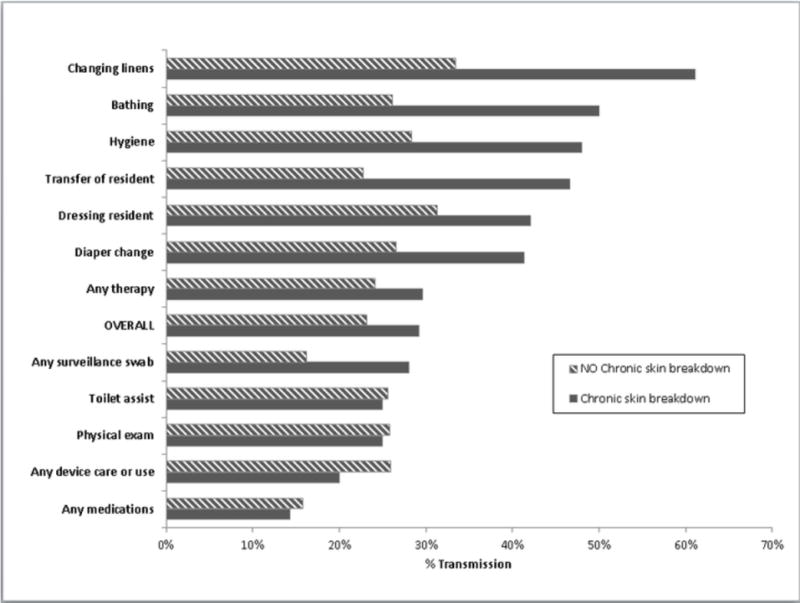

We also assessed whether resident characteristics increased the risk of transmission. We hypothesized that the presence of body secretions would increase gown and glove contamination. Diarrhea, heavy wound secretions and heavy respiratory secretion were rare in the study population (Table 1). Thus we assessed stool incontinence (18%) and chronic skin breakdown (21%). Residents with stool incontinence did not have an increase in gown or glove contamination (data not shown). Residents with chronic skin breakdown had higher rates of gown and glove contamination during high risk activities which were statistically significant for transferring (p=0.02), changing diapers (p=0.02) and dressing (p=0.05) (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

MRSA Transmission to Gowns of Healthcare Personnel during care of MRSA colonized residents (n=113) by Type of Care provided and presence of chronic skin breakdown (e.g. pressure ulcers) during 952 interactions

Figure 3.

MRSA Transmission to Gloves of Healthcare Personnel during care of MRSA colonized residents (n=113) by Type of Care provided and presence of chronic skin breakdown (e.g. pressure ulcer) during 950 interactions

Discussion

MRSA transmission to gowns and gloves was common with 14% of gowns and 24% of gloves contaminated with MRSA after resident interactions; spa typing supports that this is MRSA from the resident. Transmission to gloves was more common than transmission to gowns. High risk care activities often involved more than one type of care. We found that residents with chronic skin breakdown were more likely to transmit MRSA during high risk activities than residents without chronic skin breakdown.

Twenty-eight percent of residents were colonized with MRSA in nares and/or perianal skin. This result is similar to those of other studies done over the last 10 years in the United States. Mody et al. found a prevalence of 29% in residents without medical devices from 14 nursing homes.12 Huang and colleagues found a prevalence of 26% from the anterior nares in 26 nursing homes in Orange County.13 Evans and colleagues reported a mean admission prevalence of 29% from 133 VA long term care facilities.14 Twenty-two percent of patients in 6 skilled nursing facilities in Wisconsin were colonized with MRSA in nares, skin of the axilla and groin, or perianal skin.15

The risk of gown and glove contamination is high when providing care to MRSA colonized residents. This is consistent with uniform or clothing contamination rates reported by Garpard and colleagues in nursing home staff.16 Our results suggest when to wear gowns and gloves by defining high risk care-activities for transmission. These high risk care-activities were all high contact activities of daily living and often did not involve overt contact with body fluids, skin breakdown or mucous membranes. This indicates the need to modify current CDC standards of care involving the use of gowns and gloves in this setting because under Standard Precautions, gowns and gloves would not be worn for what we define as high risk care.17

Surprisingly, we found that 5% of glove and gown interactions were positive during interactions with residents not colonized with MRSA. Potential sources of this MRSA include residents colonized with MRSA at sites other than the anterior nares and perianal skin, the physical environment of the resident’s room which is often shared, the nursing home environment, the study gowns and gloves, and healthcare personnel with MRSA colonization.18 There were two MRSA negative residents with three positive gown and glove specimens suggesting that they had MRSA colonization and we did not detect it on enrollment cultures possibly because they were colonized at other sites.12 Prior studies which have cultured unused gloves have found that gloves are not likely to be contaminated with MRSA prior to use.19 Our finding suggests that MRSA is ubiquitous in the nursing home environment and also provides context for evaluating the contamination rates in MRSA colonized residents. Rates of contamination seen with providing medications and glucose monitoring are similar to rates when interacting with non-colonized residents.

The study has several limitations. The contamination of gowns and gloves of healthcare personnel is a surrogate measure for MRSA transmission. We do not know how often MRSA transmission to HCP clothing or hands would result in transmission to other residents. Hand hygiene, glove and gown use would typically prevent MRSA transmission to another resident. Although gown and glove contamination is a surrogate measure, it is a logical first step in the chain of transmission. A cluster randomized trial of universal use of gowns and gloves in 20 ICUs demonstrated a 40% reduction in MRSA acquisition in the intervention units.20 A recent cluster-randomized study involving high-risk nursing home residents with indwelling devices, showed that a multi-modal strategy that included preemptive use of barrier precautions reduced new MRSA acquisitions by 22%.21 Furthermore since adherence of HCP to recommended hand hygiene procedures has been poor (overall average 40%), hand contamination could easily lead to transmission.22,23 Because HCP participation was anonymous, we could not adjust for repeated measurements from the same staff member; however, we recruited from 13 different nursing homes and therefore it is highly likely that a variety of HCP participated. We did adjust for multiple observations of the same type of care on the same resident using generalized estimating equations. Consent bias may also affect study outcome measures. Residents who consented to participate in the study may differ in important ways from those who did not consent; however, we engaged legally authorized representatives in the consent process to obtain a representative sample and limit this bias.

The study also has numerous strengths. It was a multisite, prospective study involving diverse nursing homes in two geographically disparate sites. Data were collected in community based nursing homes which comprise the majority (94%) of nursing homes in the U.S.24 The demographics of the study population are generally representative of the U.S. nursing home population with regard to gender and ethnicity. Nationally, females comprise 71% of nursing home residents versus 70% in our sample.25 Our sample was 77% non-Hispanic white versus 79% of U.S. nursing home users.26 Finally, we identified MRSA colonization using surveillance cultures at enrollment.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to study MRSA transmission by type of care activity and resident characteristics in nursing homes. Glove contamination was significantly higher than gown contamination reinforcing the importance of hand hygiene to prevent the transmission of MRSA and other bacteria. We identified high risk care activities including: dressing, transferring, providing hygiene (brushing teeth, combing hair), changing linens and changing diapers. This data provides more concrete guidance for the use of gowns during Standard Precautions as well as potential modifications to Contact Precautions for MRSA colonized residents. Finally we identified chronic skin breakdown as a resident characteristic that increased the risk of MRSA transmission to both gowns and gloves (perhaps because the area of skin breakdown was colonized with MRSA). The presence of chronic skin breakdown (e.g. a pressure ulcer) could be used as a marker of residents at high risk for MRSA (or other MDRO) transmission as suggested in a recent editorial.17 These residents could be placed on a modified form of Contact Precautions in which gowns and gloves are worn for high risk types of care similar to the recent cluster-randomized study discussed earlier which focused on residents with medical devices.21

New MRSA acquisition in nursing homes is substantial.27,28 Our study defines interactions that increase the risk of transmission and suggests modifications to the current indications of gown and glove use in this setting.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. Project supported by: AHRQ award 1R18HS019979-01A1; Dr. Sorkin is supported by the Baltimore Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center; National Institute on Aging grant 5 P30 AG028747; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant 5 P30 DK072488; Dr. Mody is supported by the Ann Arbor VA Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center, National Institute on Aging grants R01 AG032298, R01 AG41780, R18 HS019979 and University of Michigan Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30 AG024824).

Thank yous. We thank the staff and residents of the participating nursing homes.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: Leslie Norris, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 10 South Pine Street, MTSF Room 334E, Baltimore, MD 21201

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee Management of Multidrug-Resistant Organisms In Healthcare Settings. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trick WE, Weinstein RA, DeMarais PL, et al. Comparison of routine glove use and contact-isolation precautions to prevent transmission of multidrug-resistant bacteria in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2003–2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes C, Tunney M, Bradley MC. Infection control strategies for preventing the transmission of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in nursing homes for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD006354. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006354.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johannessen T. Controlled trials in single subjects. 1. Value in clinical medicine. BMJ. 1991;303(6795):173–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6795.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan DJ, Rogawski E, Thom KA, et al. Transfer of multidrug-resistant bacteria to healthcare workers’ gloves and gowns after patient contact increases with environmental contamination. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1045–1051. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823bc7c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan DJ, Liang SY, Smith CL, et al. Frequent Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Contamination of Gloves, Gowns, and Hands of Healthcare Workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010 doi: 10.1086/653201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder GM, Thom KA, Furuno JP, et al. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci on the gowns and gloves of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(7):583–589. doi: 10.1086/588701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Long-Term Care Facility Resident Assessment Instrument User’s Manual. 2014 Version 3.0. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Wayne, PA: Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, Rothganger J, Turnwald D, Vogel U. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(12):5442–5448. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strommenger B, Kettlitz C, Weniger T, Harmsen D, Friedrich AW, Witte W. Assignment of Staphylococcus isolates to groups by spa typing, SmaI macrorestriction analysis, and multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(7):2533–2540. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00420-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mody L, Kauffman CA, Donabedian S, Zervos M, Bradley SF. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in nursing home residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(9):1368–1373. doi: 10.1086/586751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson LO, Reynolds C, Spratt BG, et al. Diversity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from residents of 26 nursing homes in Orange County, California. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(11):3788–3795. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01708-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans ME, Kralovic SM, Simbartl LA, et al. Nationwide reduction of health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in Veterans Affairs long-term care facilities. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(1):60–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crnich CJ, Duster M, Hess T, Zimmerman DR, Drinka P. Antibiotic resistance in non-major metropolitan skilled nursing facilities: prevalence and interfacility variation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(11):1172–1174. doi: 10.1086/668018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaspard P, Eschbach E, Gunther D, Gayet S, Bertrand X, Talon D. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus contamination of healthcare workers’ uniforms in long-term care facilities. J Hosp Infect. 2009;71(2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone ND. Revisiting Standard Precautions to Reduce Antimicrobial Resistance in Nursing Homes. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strausbaugh LJ, Jacobson C, Sewell DL, Potter S, Ward TT. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in extended-care facilities: experiences in a Veterans’ Affairs nursing home and a review of the literature. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1991;12(1):36–45. doi: 10.1086/646236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rock C, Harris AD, Reich NG, Johnson JK, Thom KA. Is hand hygiene before putting on nonsterile gloves in the intensive care unit a waste of health care worker time?–a randomized controlled trial. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(11):994–996. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris AD, Pineles L, Belton B, et al. Universal glove and gown use and acquisition of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the ICU: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(15):1571–1580. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mody L, Krein SL, Saint SK, et al. A Targeted Infection Prevention Intervention in Nursing Home Residents With Indwelling Devices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyce JM, Pittet D, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings. Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-16):1–45. quiz CE1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson BL, Dwyer DM, Ussery XT, Denman S, Vacek P, Schwartz B. Handwashing and glove use in a long-term-care facility. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18(2):97–103. doi: 10.1086/647562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrington C, Carrillo H, Dowdell M, Tang P, Blank B. Nursing, Facilities, Staffing, Residents, and Facility Deficiencies, 2005 Through 2010. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, Strahan GW. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. Vital Health Stat. 2009;13(167):1–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R. Long-term care services in the United States: 2013 overview. 2013:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Loeb MB, et al. Infection management and multidrug-resistant organisms in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1660–1667. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisch J, Lansing B, Wang L, et al. New acquisition of antibiotic-resistant organisms in skilled nursing facilities. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(5):1698–1703. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06469-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]