Abstract

The association of congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) with congenital heart disease is rare. We present the case of a 6-month-old child with atrial septal defect and pulmonary hypertension (PH) who presented with severe respiratory distress and hypoxia. The patient underwent right lobectomy for CPAM. With timely management, real-time monitoring, one lung ventilation, and adequate analgesia, we were able to extubate the child in the immediate postoperative period. We conclude that with meticulous planning and multidisciplinary team approach, such complex cases can be managed successfully.

Keywords: Atrial septal defect, Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, Congenital pulmonary airway malformation, One-lung ventilation, Pulmonary hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM), a congenital lung lesion in children is the result of an embryologic insult in early gestation causing maldevelopment of the terminal bronchiolar structures. This usually occurs in a single lobe causing ipsilateral lung compression, pulmonary hypoplasia, and occasional mediastinal shift. Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common birth defect which occurs in 1 in 125 live births. Left to right shunts such as atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) account for 50% of the CHDs. Pulmonary hypertension (PH), as a complication, can develop in ASD, although less frequently. Congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) is an independent etiological factor for the development of PH. Development of PH is associated with increased risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality.[1]

The association of CPAM and CHD is rare and accounts for 15–20% of cases. We present the case of a 6-month-old child posted for lobectomy, with CPAM and ASD, who developed PH, which resulted in a reversal of the shunt.

CASE REPORT

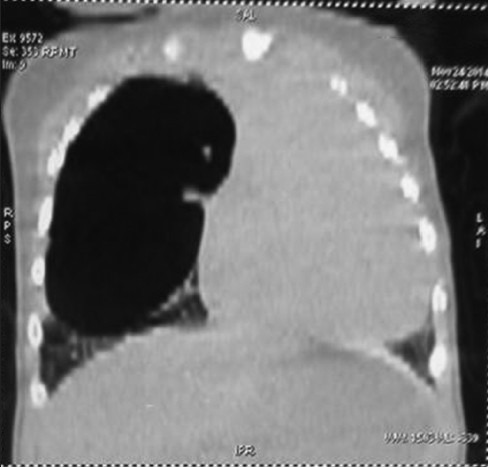

A 6-month-old female child weighing 4 kg diagnosed as ASD with bidirectional shunt and severe PH was posted for the right upper and middle lobectomy. She presented with tachypnea, chest indrawing, and intercostal retractions. On examination, the vitals were as follows: Pulse rate - 148/min, respiratory rate - 56/min, and O2 saturation - 68% on air. On auscultation, there were decreased breath sounds on the right upper and middle zone with normal heart sounds. Computerized tomography (CT) thorax showed CPAM with cardiomegaly [Figures 1 and 2]. Two-dimensional echo revealed moderate ostium secundum ASD with bidirectional shunt and moderately severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) of 53 mmHg. A high-risk consent including the requirement for postoperative mechanical ventilation was obtained from the parents. Patient was premedicated with intravenous (i.v.) midazolam 0.03 mg/kg, i.v. ketamine 1 mg/kg, and i.v glycopyrrolate 4 mcg/kg. Anesthesia was induced with i.v fentanyl 5 μg/kg, 100% O2, sevoflurane, and maintaining spontaneous respiration. The patient's airway was secured with 4.0 mm endotracheal tube (ETT) introduced into the left main bronchus. There was a drop in the saturation which could not be improved in spite of bringing back the ETT into the trachea. This was anticipated, and the surgeon was ready with a large bore cannula to decompress the lung. Upon insertion of the 18 gauge cannula in the right 2nd intercostal space, saturation improved, and the ETT was repositioned back into the left main bronchus. In addition to standard monitors, invasive monitoring was performed using femoral line for CVP and radial arterial line for blood pressure. A 20 gauge thoracic epidural catheter was introduced at T7/T8 interspace, and the catheter was fixed at 8 cm. After a test dose of 0.4 cc 1% lignocaine with adrenaline (1:200,000), analgesia was maintained with intermittent bolus doses of 0.2% bupivacaine. Anesthesia was maintained with oxygen/air, sevoflurane (clinical minimum alveolar concentration of 1.0), and spontaneous respiration. Nondepolarizing muscle relaxant atracurium 0.6 mg/kg was given only after the right thoracotomy incision. A cardiothoracic surgeon was standby for the procedure. The intraoperative finding was a large cyst arising from the upper and middle lobe with dense adhesions and no demarcation between the upper and middle lobe; the lower lobe was normal with thick hypertrophied vessels probably secondary to PH. Upper and middle lobectomy was performed [Figure 3]. The child received 10 ml/kg of 2% dextrose ringer lactate. Blood loss was around 25% of the blood volume and was replaced with equal volume of blood. Intraoperative hemodynamics was well-maintained. Operative time was 2 h. At the end of surgery, the patient was shifted to high dependency unit and extubated 1 h later.

Figure 1.

Cystic lesion in the right lung with mediastinal shift

Figure 2.

Cystic lesion in the right lung with mediastinal shift-transverse section

Figure 3.

Upper and middle lobe of right lung

DISCUSSION

CPAM, previously known as Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM) is a congenital disorder of the lung with a reported incidence of 1:25,000–1:35,000. About 15–50% of cases of congenital cystic lung disease are reported to be CPAM.[2,3,4] Usually, an entire lobe of the lung is replaced by a nonworking cystic piece of abnormal lung tissue. The underlying cause is not known. Surgical resection is the gold standard for the management of CPAM for both pathological diagnosis and treatment.[5] The association of CPAM and CHD is rare and accounts for 15-20% of cases.[6] Respiratory symptoms can be present at birth and PH can be seen secondary to either compression of the cysts or from rupture and resultant pneumothorax. Type 2 CPAM has the worst prognosis because they are often associated with other defects such as ASD, VSD, PDA, and other renal and skeletal anomalies.[7]

PH is a complication of CHD, particularly in patients with left-to-right (systemic-to-pulmonary) shunts. Pretricuspid shunt patients (i.e. ASD or unobstructed anomalous pulmonary venous return) generally do not develop PH at all or present with PH in adulthood.[8] Persistent exposure of the pulmonary vasculature to increased blood flow and pressure may result in vascular remodeling and dysfunction. This leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and, ultimately, to reversal of the shunt or bidirectional shunts.[9]

PH seen in our case can be attributed to the combination of CPAM with ASD causing bidirectional shunt and further comprising the oxygenation of the patient.

The anesthetic goals are to prevent hypoxia, acidosis, and hypercarbia which further increase PVR, to prevent reduction in systemic vascular resistance and depression of myocardial function associated with the use of anesthetic agents. Surgical assistance should be readily available for thoracotomy incision/needle decompression in the case of severe desaturation on induction.

One-lung ventilation (OLV) improves surgical access and may reduce blood loss. CPAM may contain fluid varying from clear to purulent in nature. OLV also minimizes trauma to the limited residual normal lung tissue[10] and protects normal lung from contralateral contamination.

Our plan was to extubate this child early to avoid positive pressure ventilation and the possible complications of barotrauma. Provision of good analgesia was, therefore, a priority.

We emphasize the need for readiness to immediately decompress the lung, as positive pressure ventilation can jeopardize oxygenation with the expansion of the cyst or possible complication of pneumothorax. Surgery must be performed by an experienced surgeon. Nitrous oxide was not used because of its potential for cyst expansion. Muscle relaxant was given only after the thoracotomy incision.

In congenital lung lesions such as CPAM, CT is the optimum postnatal diagnostic imaging modality, pulmonary resection is the surgical procedure of choice, expected survival is good, and PH is the most common cause of mortality.[1]

A complete workup including history and clinical examination, focusing on cardiac signs and symptoms, and other systems including renal and skeletal systems, and previous catheterization procedures are essential as CPAM is associated with anomalies of other systems. Provision of care by an expert team is essential for a successful outcome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schwartz MZ, Ramachandran P. Congenital malformations of the lung and mediastinum - A quarter century of experience from a single institution. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:44–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stocker JT. The respiratory tract. In: Stocker JT, Dehner LP, editors. Pediatric Pathology. 2nd ed. Ch. 13. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Company; 1992. pp. 466–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sittig SE, Asay GF. Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation in the newborn: Two case studies and review of the literature. Respir Care. 2000;45:1188–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan C, Lee YS, Taso PC, Jeng MJ, Soong WJ. Congenital pulmonary airway malformation type IV: A case report. J Pediatr Resp Dis. 2013;9:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall KW, Blane CE, Teitelbaum DH, van Leeuwen K. Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation: Impact of prenatal diagnosis and changing strategies in the treatment of the asymptomatic patient. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:1551–4. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.6.1751551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolde S, Pudale S, Pandit G, Ruikar K, Ingle SB. Congenital pulmonary airway malformation: A report of two cases. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:470–3. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i5.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Stocker JT. From the archives of the AFIP: Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation. Radiographics. 1991;11:868. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.11.5.1947321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vongpatanasin W, Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. The Eisenmenger syndrome in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:745–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood P. The Eisenmenger syndrome or pulmonary hypertension with reversed central shunt. I. Br Med J. 1958;2:701–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5098.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammer GB. Pediatric thoracic anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2002;20:153–80. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(03)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]