Abstract

In this case report study a 41-year-old man envenomed by a bee sting and diagnosed as Kounis syndrome secondary to hymenoptera envenomation. The patient developed a typical course of myocardial infarction, but the electrocardiogram changes were reversed to almost normal limits. He had a nonsignificant mild lesion in the proximal port of right coronary artery in coronary angiography. The case recovered and discharged after 6 days hospitalization. The clinical implications and pathophysiology of this dangerous association are discussed.

Keywords: Bee sting, Kounis syndrome, Myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

Kounis syndrome first reported in the American Heart Journal in 1950 with a case of a prolonged allergic reaction to penicillin[1] and first described in 1991 by Kounis and Zavras. It is also known as “allergic angina syndrome” or “allergic myocardial infarction.”[2] More specifically, coronary vasospasm and myocardial infarction secondary to allergic reactions known as the Kounis syndrome.[2,3] It is associated with several causes that may activate hypersensitivity pathways and induce mast cells degranulation.[4] Signs and symptoms of this syndrome may include chest pain, with or without raised troponins and cardiac enzymes, dyspnea, faintness, nausea, vomiting, syncope, pruritus, urticaria, diaphoresis, pallor, palpitations, hypotension, and bradycardia.[4] Several causes have been reported in relation to Kounis syndromes such as medications, a number of conditions, and a variety of environmental exposures. The latter includes stings by ants, bees, wasps, jellyfishes, as well as grass cutting, poison ivy, latex contact, limpet ingestion, millet allergy, shellfish eating, and viper venom poisoning.[3] We report a case who was envenomed by bee sting and had acute myocardial infarction accompanied by electrocardiogram (ECG) changes. This study was aimed to present this case report to highlight this rare syndrome which physicians should be aware of such a complication to make a prompt diagnosis and initiate early treatment.

CASE REPORT

History

A 41-year-old experienced multiple stung by honeybees on the head and neck regions admitted to Emergency Department of hospital. He reported a short period of dizziness and respiratory discomfort after stung. The patient had a generalized erythematous rash over the face, neck, and thorax regions accompanied by itching and wheezing in admission time. He complained from sweating, became pale, severe retrosternal pain radiating to both arms associated with nausea and vomiting.

The patient was smoker and opium addict (3–4 times a week), with no history of dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, or other significant illness. He was asymptomatic with appropriate daily functional. Moreover, he had the previous history of bronchial asthma but without previous history of allergy, rhinitis, dermatitis, or eczema.

Physical examination and investigations

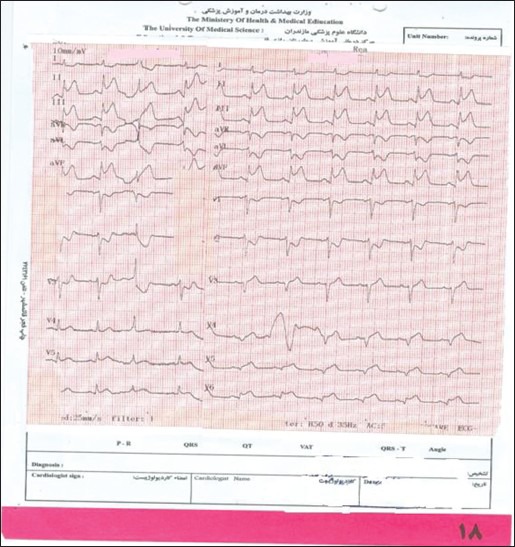

Blood samples were taken for cardiac enzymes: Troponins with 1.2 mg/ml and creatine phosphokinase (CPK) with 424 ng/ml and CPK MB: 357, all investigations, including abdomen, central nervous system, kidney function, hemogram, urine, random blood sugar, cardiac biomarkers, and chest X-ray, were normal. Hematocrit and platelet counts also were in the normal limit. He was afebrile with blood pressure of 115/75 mmHg and the pulse revealed sinus tachycardia 102 beats/min regular with oxygen saturation 98%. The ECG revealed elevation of ST segment in leads I, II, III, aVF, V4–V6, and ST segment depression in leads aVL, compatible with acute inferior and posterior myocardial infarction [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Electroencephalography of case in admission time

Treatment

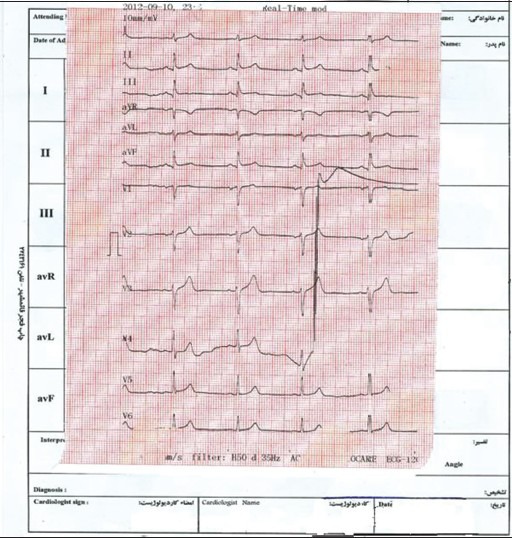

He was immediately administered 325 mg aspirin medicine, 10 mg morphine, 10 mg chlorpheniramin, and nitroglycerin infusion of 1.2 μg/kg/min also prescribed intravenously. Following primary management, the patient shifted to the coronary care unit and thrombosed with streptokinase shortly following pain. In this stage, ECG changed to normal and ST segment elevation return to normal without Q wave [Figure 2]. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed mild mitral regurgitation, mild diastolic dysfunction, and left ventricular ejection fraction 45%.

Figure 2.

Electroencephalography of patient after treatment

Phosphokinase was 1680 ng/ml after 48 h and the troponin also was in the normal range after 2 weeks. He had nonsignificant mild lesion in proximal port of right coronary artery in coronary angiography. Other coronary arteries had no lesion.

The medication prescribed for patient was as followings: Aspirin, clopidogrel, beta-blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and nitrocantin 2.6 mg and statin creatine. The case had uncomplicated hospital follow-up and was discharged uneventfully on 6th day after admission.

DISCUSSION

Exposure to bee stings is common worldwide; however, the development of myocardial infarction secondary to bee stings is a rarely reported event.[5] We reported the case of a 41-year-old man who was envenomed by a bee sting and had myocardial infarction with ST elevation. The patient developed an erythematous rash when he was stung by bees. This was followed by the symptoms and signs of acute myocardial infarction confirmed by the elevated cardiac enzymes and troponins. A rare manifestation of such reactions is angina and coronary syndromes, and this is referred to as the Kounis syndrome.[3] Allergic reactions of any grading[6] to honeybee or wasp stings are seen in up to 5% of the total population in Europe and the USA,[7] there was not information about prevalence of this problem in Iranian population. The reactions are vary greatly in severity with manifestations ranging from skin reactions such as rash and itching to respiratory, gastrointestinal or cardiovascular reactions, as in presented case. In a few patients, especially in those with severe anaphylactic reaction an association with mastocytosis has been reported.[8] Flying hymenoptera venoms are mainly aqueous solutions that contain peptides, proteins, and vasoactive amines including histamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine, dopamine, and 5-hydroxy tryptamine.[9] These substances are responsible for direct venom cardiotoxicity and several of the proteins and peptides are allergenic. It has been estimated that about 1500 stings would be required to deliver a lethal dose of hymenoptera venom for an allergic adult with 70 kg weight.[8]

Phospholipase A2 is a key enzyme for activation of the metabolism of the arachidonic acid. During the metabolism of the arachidonic acid an array of cytokines and chemokines are released. These include leukotrienes by the lipoxygenase pathway and prostaglandins such as thromboxane by cyclooxygenase pathway. These mediators have been incriminated in many clinical and laboratory studies to induce coronary artery spasm and/or acute myocardial infarction.[1] Two types of Kounis syndrome have been characteristically described.[4] Type I variant includes patients with normal coronary arteries in whom the acute allergic insult induces either coronary artery spasm leading to unstable angina with normal cardiac enzymes and troponins or coronary artery spasm progressing to acute myocardial infarction. This variant might represent a manifestation of endothelial dysfunction or microvascular angina. Type II variant of Kounis syndrome includes patients with preexisting, albeit occult, an atheromatous disease in whom acute allergic episode can induce plaque erosion or rupture manifesting as an acute myocardial infarction. Concerning our case, although he had no significant risk factors and was asymptomatic in ordinary activities, he had occult atheromatous coronary artery disease. As it is characteristic of the Type II variant of Kounis syndrome, the acute allergic episode after the bee sting most probably induced plaque erosion or rupture manifesting as acute myocardial infarction.

Signs and symptoms may include chest pain, with or without raised troponins and cardiac enzymes, dyspnea, faintness, nausea, vomiting, syncope, pruritus, urticaria, diaphoresis, pallor, palpitations, hypotension, and bradycardia.[4] In presented case also, the following signs existed: Dizziness, espiratory, discomfort, and erythematous rash over the face, neck, and thorax regions accompanied by itching and wheezing, sweating, pale, and severe retrosternal pain radiating to both arms associated with nausea and vomiting.

There are several case reports dealing with cardiovascular complications after hymenoptera stings. Commonly, patients are hypotensive or a few are hypertensive on admission time[10] but our case was normal in blood pressure same as case reported by Ioannidis et al.[11]

In our case, the ECG revealed elevation of ST segment in leads I, II, III, aVF, V4–V6 and ST segment depression in leads aVL, compatible with acute inferior and posterior myocardial infarction. While coronary angiography revealed normal coronary arteries. The same result reported in one Turkish study that while echocardiography showed segmental wall motion abnormality, coronary angiography revealed normal coronary arteries in the first five patients.[12] In the case reported by Yang et al. also 36 h after treatment the ECG revealed no abnormality and angiography revealed almost normal coronary arteries.[10]

Recent studies have shown that the mast cells,[13] histamine,[14] tryptase,[15] and arachidonic acid products[16] have been found present in acute coronary syndromes of nonallergic etiology. A common pathway seems to exist.[4] Still the mechanism of this syndrome is unclear.

Studying the responses to pharmacological agents at mast cells protection and stabilization may shed light on potential therapeutic strategies that may apply to the more generalized area of interference with plaque erosion or rupture and primary as well as secondary prevention of acute coronary syndromes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfister CW, Plice SG. Acute myocardial infarction during a prolonged allergic reaction to penicillin. Am Heart J. 1950;40:945–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(50)90191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kounis NG, Zavras GM. Histamine-induced coronary artery spasm: The concept of allergic angina. Br J Clin Pract. 1991;45:121–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kounis NG. Kounis syndrome (allergic angina and allergic myocardial infarction): A natural paradigm? Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikolaidis LA, Kounis NG, Gradman AH. Allergic angina and allergic myocardial infarction: A new twist on an old syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:508–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kogias JS, Sideris SK, Anifadis SK. Kounis syndrome associated with hypersensitivity to hymenoptera stings. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114:252–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown SG. Clinical features and severity grading of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:371–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludolph-Hauser D, Ruëff F, Fries C, Schöpf P, Przybilla B. Constitutively raised serum concentrations of mast-cell tryptase and severe anaphylactic reactions to Hymenoptera stings. Lancet. 2001;357:361–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohr SM, Rich MW, Silver KH. Shortness of breath, syncope, and cardiac arrest caused by systemic mastocytosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:592–4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moffitt JE. Allergic reactions to insect stings and bites. South Med J. 2003;96:1073–9. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000097885.28467.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang HP, Chen FC, Chen CC, Shen TY, Wu SP, Tseng YZ. Manifestations mimicking acute myocardial infarction after honeybee sting. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2009;25:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ioannidis TI, Mazarakis A, Notaras SP, Karpeta MZ, Tsintoni AC, Kounis GN, et al. Hymenoptera sting-induced Kounis syndrome: Effects of aspirin and beta-blocker administration. Int J Cardiol. 2007;121:105–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gökdeniz T, Kaya H, Özkan M. Kounis syndrome: First series in Turkish patients. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2009;9:59–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovanen PT, Kaartinen M, Paavonen T. Infiltrates of activated mast cells at the site of coronary atheromatous erosion or rupture in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;92:1084–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clejan S, Japa S, Clemetson C, Hasabnis SS, David O, Talano JV. Blood histamine is associated with coronary artery disease, cardiac events and severity of inflammation and atherosclerosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6:583–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filipiak KJ, Tarchalska-Krynska B, Opolski G, Rdzanek A, Kochman J, Kosior DA, et al. Tryptase levels in patients after acute coronary syndromes: The potential new marker of an unstable plaque? Clin Cardiol. 2003;26:366–72. doi: 10.1002/clc.4950260804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takase B, Maruyama T, Kurita A, Uehata A, Nishioka T, Mizuno K, et al. Arachidonic acid metabolites in acute myocardial infarction. Angiology. 1996;47:649–61. doi: 10.1177/000331979604700703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]