Abstract

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) is a rare lung disease characterized by accumulation of excessive lung surfactant in the alveoli leading to restrictive lung functions and impaired gas exchange. Whole lung lavage (WLL) is the treatment modality of choice, which is usually performed using double lumen endobronchial tube insertion under general anesthesia and alternating unilateral lung ventilation and washing with normal saline. It may be difficult to perform WLL in patients with severe hypoxemia wherein patients do not tolerate single lung ventilation. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support (ECMO) has been used in such patients. We report a patient with autoimmune PAP following renal transplant who presented with marked hypoxemia and was managed by WLL under ECMO support.

Keywords: Double lumen tube, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, Venovenous, Whole lung lavage

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) is a rare lung disease first described by Rosen et al.[1] in 1958 which is characterized by abnormal accumulation of excessive surfactant[2] in the alveoli. PAP may occur in three forms: Autoimmune PAP, which accounts for more than 90% of cases, whereas congenital and secondary PAP account for the remaining 10%. Autoimmune PAP[3] is characterized by the presence of neutralizing autoantibodies against granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) causing altered alveolar macrophage function and inability to catabolize surfactant resulting in its accumulation. Secondary PAP can occur in patients suffering from immunodeficiency disorders, infections, for example, nocardia or pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, hematologic malignancies, and with exposures to heavy metal dusts. Whole lung lavage (WLL) performed under general anesthesia is the treatment modality of choice for symptomatic PAP. However, this procedure may be difficult in patients with severe hypoxemia. We report a patient with autoimmune PAP, who presented with respiratory failure wherein WLL was successfully performed using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of ECMO used for this indication from India.

CASE REPORT

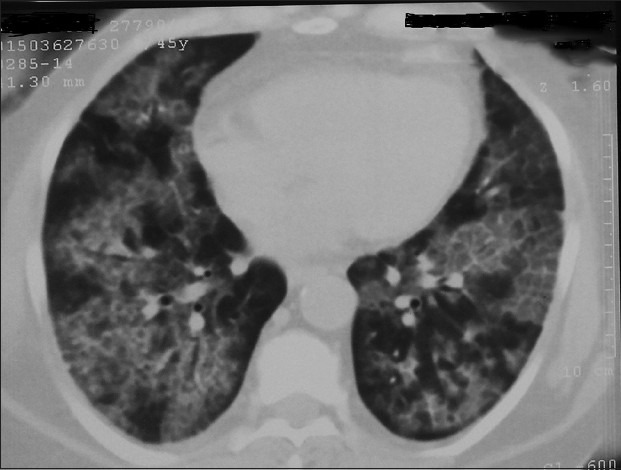

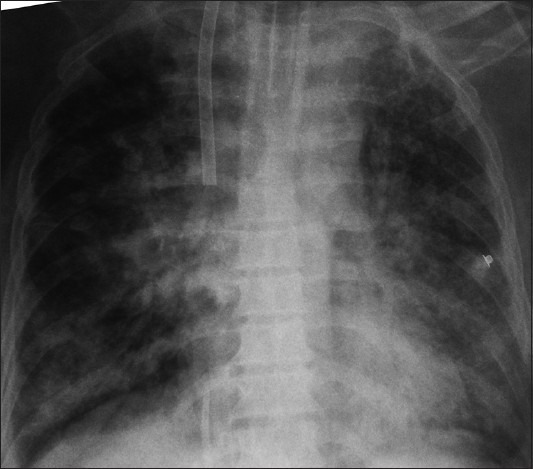

A 45-year-old female presented with a 7-month history of a dry cough and progressive dyspnea. Patient was diagnosed to have chronic kidney disease and had undergone allogenic renal transplant 2 years ago. She had subsequent graft failure requiring maintenance hemodialysis for four months. At the time of presentation, the patient was tachypnoeic (respiratory rate 30/min) with oxygen saturation of 90% on 6 L oxygen via face mask and alveolar-arterial gradient of 99 mmHg. Chest auscultation revealed bilateral scattered crepitations. Chest radiograph [Figure 1] demonstrated bilateral alveolar infiltrates. Computed tomography scan of thorax [Figure 2] showed diffuse ground glass appearance with interlobular septal thickening suggestive of crazy paving pattern. Patient underwent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) which showed opaque, milky-white return with granular white sediments. Cytology of BAL fluid and transbronchial lung biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of PAP. GM-CSF antibody levels were elevated (109 mcg/ml; normal <5 mcg/ml). Patient had no significant past medical and exposure history. A diagnosis of PAP was established. Patient had already received subcutaneous GM-CSF injection for 3 months before presentation with persistent deterioration of hypoxemia. In view of worsening symptoms, WLL using a double-lumen endobronchial tube (DLT) under general anesthesia was planned. However, the procedure had to be terminated prematurely due to bronchospasm, severe oxygen desaturation, and hemodynamic instability even on transient single lung ventilation using DLT. Further therapeutic options were discussed with the patient and WLL using ECMO was planned. The patient was intubated with 35 Fr left-sided DLT under general anesthesia. During the process of DLT confirmation using DLT, the patient developed severe hypoxemia (PaO2 - 25 mm Hg) on 100% FiO2. A quick bronchoscopy was performed and tube position was ensured. Intravenous unfractionated heparin (8000 IU) was given and initial value of activated clotting time (ACT) was around 250 s. Patient underwent cannulation through right internal jugular vein (19 Fr return cannula) into right atrium above tricuspid valve and right femoral vein (24 Fr catheter drainage cannula) at the inferior cavoatrial junction. The tip placements were confirmed with transesophageal echocardiography. Venovenous ECMO was initiated after connecting both cannulae to the ECMO circuit using the centrifugal pump and polymethylpentene membrane oxygenator (Quadrox PLS; Maquet, Hirrlingen, Germany). Flow rate of ECMO was maintained between 3 and 4 L/min at rpm of 3500/min to 4500/min during whole procedure. Heparin infusion was started at 50 units/kg/h to maintain ACT around 180–200 s. Sequential bilateral WLL was performed using multiple aliquots of 500–750 ml of warm normal saline. The passive return fluid was collected and measured using separate bottles. Around 18 L of normal saline was used during the process and 7.5 L of return fluid was collected from each lung. Initial fluid was turbid with milky white sediments which gradually cleared on subsequent returns [Figure 3]. Patient developed severe hypotension and bradycardia on instillation of normal saline into the lungs after initiation of ECMO and hemodynamics were maintained with infusion of noradrenaline and adrenaline both in a dose of 0.05 mcg/kg/min and the oxygen saturation remained above 90%. After the procedure, DLT was replaced with single lumen endotracheal tube and patient was shifted to ICU along with ECMO support. Hemodynamics remained stable in ICU under inotropic support. ECMO was weaned off gradually by reducing flow rates over the next 36 h; ventilation was ensured with pressure support ventilation. Postprocedure X-ray [Figure 4] showed improvement in the lung opacities. Patient was shifted with endotracheal tube in situ to the parent department for further management.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray before whole lung lavage

Figure 2.

Computed tomography chest before whole lung lavage

Figure 3.

Lung lavage material

Figure 4.

Chest X-ray after whole lung lavage

DISCUSSION

Accumulation of excessive surfactant in PAP causes restrictive pulmonary function abnormality leading to hypoxemia and can progress to respiratory failure and death. WLL is the treatment modality of choice for severe PAP. Since its first description in 1967 by Ramirej et al.,[4] WLL is still the gold standard treatment modality for PAP. The aim of WLL is to remove excessive proteinaceous material from the alveoli. Other treatment modalities include subcutaneous[5] or inhaled[6] GM-CSF and intravenous rituximab[7] with variable success rates. Conventionally, WLL is performed under GA with DLT insertion and patients tolerate the procedure well. However, in some patients, unilateral lung ventilation during WLL induces severe desaturation with fatal consequences. The risk of hypoxemia is even greatest during the drainage of lavage fluid due to shunting of blood through the nonventilated lung. Venovenous ECMO support is a safer alternative to ensure adequate oxygenation and is helpful in such circumstances. There are some case reports[8,9,10] of WLL performed using ECMO support for management of PAP.

Our patient also had severe desaturation with hemodynamic instability during the initial attempt of DLT insertion. Venovenous ECMO subsequently allowed us to perform the procedure successfully without clinically significant complications. This shows that ECMO may be used as a supporting modality for oxygenation in patients with PAP and underlying renal dysfunction who present with severe hypoxemia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosen SH, Castleman B, Liebow AA. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 1958;258:1123–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195806052582301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Golde LM, Batenburg JJ, Robertson B. The pulmonary surfactant system: Biochemical aspects and functional significance. Physiol Rev. 1988;68:374–455. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.2.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trapnell BC, Carey BC, Uchida K, Suzuki T. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, a primary immunodeficiency of impaired GM-CSF stimulation of macrophages. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:514–21. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramirez J, Schultz RB, Dutton RE. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: A new technique and rationale for treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1963;112:419–31. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1963.03860030173021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkateshiah SB, Yan TD, Bonfield TL, Thomassen MJ, Meziane M, Czich C, et al. An open-label trial of granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor therapy for moderate symptomatic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Chest. 2006;130:227–37. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tazawa R, Trapnell BC, Inoue Y, Arai T, Takada T, Nasuhara Y, et al. Inhaled granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor as therapy for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1345–54. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0978OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borie R, Debray MP, Laine C, Aubier M, Crestani B. Rituximab therapy in autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1503–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00160908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen ES, Elpern E, Silver MR. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis causing severe hypoxemic respiratory failure treated with sequential whole-lung lavage utilizing venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A case report and review. Chest. 2001;120:1024–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.3.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centella T, Oliva E, Andrade IG, Epeldegui A. The use of a membrane oxygenator with extracorporeal circulation in bronchoalveolar lavage for alveolar proteinosis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2005;4:447–9. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2005.110320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasan N, Bagga S, Monteagudo J, Hirose H, Cavarocchi NC, Hehn BT, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to support whole-lung lavage in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: Salvage of the drowned lungs. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2013;20:41–4. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0b013e31827ccdb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]