Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the attitude toward noise, perceived hearing symptoms, noisy activities that were participated in, and factors associated with hearing protection use among college students. A 44-item online survey was completed by 2,151 college students (aged 17 years and above) to assess the attitudes toward noise, perceived hearing symptoms related to noise exposure, and use of hearing protection around noisy activities. Among the participants, 39.6% experienced at least one hearing symptom, with ear pain as the most frequently reported (22.5%). About 80% of the participants were involved in at least one noise activity, out of which 41% reported the use of hearing protection. A large majority of those with ear pain, hearing loss, permanent tinnitus, and noise sensitivity was involved in attending a sporting event, which was the most reported noisy activity. The highest reported hearing protection use was in the use of firearms, and the lowest in discos/ dances. The reported use of hearing protection is associated with having at least one hearing symptom but the relationship is stronger with tinnitus, hearing loss, and ear pain (χ2 = 30.5-43.5, P < 0.01) as compared to noise sensitivity (χ2 = 3.8, P = 0.03); it is also associated with anti-noise attitudes, particularly in youth social events. Universities and colleges have important roles in protecting young adults’ hearing by integrating hearing conservation topic in the college curriculum, promoting hearing health by student health services, involving student groups in noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) awareness and prevention, and establishing noise level limitations for all on-campus events.

Keywords: College students, hearing symptoms, leisure noise, use of hearing protection, youth attitude to noise

Introduction

In the United States, an estimated 5.2 million (12.5%) of children and adolescents and 26 million (17%) of adults aged 20-69 have impaired hearing as a result of exposure to excessive loud noise and the numbers are increasing.[1] Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is one of the most common problems among youths and has been termed the “silent epidemic” — often unrecognized in the nonoccupational setting.[2] Extensive research has demonstrated that prolonged exposure to noise levels greater than 85 dBA results in permanent hearing loss.[3] Noise exposure is regulated in the workplace and thus, many of the efforts to evaluate and reduce noise exposure and risks to NIHL are focused in the occupational setting among the adult worker population. Unfortunately, no current standards or guidelines regulate nonoccupational noise exposure,[4] particularly in noisy environments wherein youth participates.

Young adults are involved in various activities (e.g., concerts, discotheques, clubs, and sporting events) that expose them to loud noise, increasing their risk of developing NIHL and other hearing symptoms. Smith et al.[5] reported that 18.8% of young adults aged 18-25 years were exposed to noise from leisure activities. In particular, exposure to amplified music (i.e., discos, rock concerts, and personal music) has been associated with hearing damage among young listeners.[6,7] Various studies have shown sound levels at rock concerts to be higher than 85 dBA. Sound levels in concert performances were reported at an average of 99.8 dBA, with a maximum of 125.6 dBA[8] while another study reported an average between 120 dBA and 140 dBA.[9] Sound levels in discotheques were reported to be hazardous, with a range of 104-112 dBA.[10] Beach et al.[11] reported young adults (18-35 years of age) being involved in high-noise activities including playing an instrument, attending a nightclub, and attending a pop concert, each of which were measured to have noise levels >100 dB.

Various studies have shown that NIHL and other hearing symptoms are increasing in the younger population in the United States[12] and abroad.[6,7,9,13] Noise in recreational and leisure activities has been linked to NIHL in the exposed population,[14] which is becoming a cause of concern for the young population because of its exposure to such activities. Transient tinnitus has been frequently observed among young adults after leisure noise exposure. Percentages of adolescents and young adults who experienced transient tinnitus after visiting discotheques, music concerts, parties, and festivals, or listening to personal music through headphones range from 20% to 85%.[4,15,16,17,18,19] Although noise exposure during early adulthood may cause reversible temporary or no immediate hearing loss, it may accelerate age-related hearing loss.[20] Moreover, chronic tinnitus was also reported in the young population.[19] Leisure noise exposure among young adults (16-25 years of age) has been shown to have a highly significant correlation with NIHL.[21] Noise exposure prevention is crucial, especially among the young population since impaired hearing is known to adversely affect the quality of life and may lead to psychological consequences such as depression, difficulty in concentrating, and emotional problems.[22]

College students generally comprise young adults who possess unique characteristics related to noise exposure, hearing loss, and hearing protection compared to other young populations. To be able to effectively promote and implement programs about noise exposure reduction and hearing conservation, the first step is to develop an understanding of the risk factors that influence the behavior of college students related to noise exposure. Studies on the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs toward noise and hearing loss among college students, their hearing symptoms, and participation in noisy activities have been previously conducted in Sweden,[23] the UK,[24] and the US.[23,25,26,27,28,29] In particular, Holmes et al.[25] studied 253 community college students in Florida, USA and reported that the results may not be generalized to the entire young adult population. Additionally, Chesky et al.[27] studied the attitudes toward noise among 467 university college students in Texas, USA and reported that further research was needed with larger and more diverse populations. Potential noise exposures, hearing symptoms, and attitudes toward noise among college students at a larger university in the southeastern US, where certain noisy youth activities may be more frequent and popular and youth culture may be different, have not been previously conducted.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the associations between attitudes toward noise, hearing problems, and use of hearing protection during noisy activities among college students at a university in North Carolina, USA. The specific aims are to:

Characterize the attitudes of college students toward noise and noise exposures;

Identify self-reported hearing symptoms related to noise exposure;

Identify noisy activities and locations that college students participate in; and

Determine the factors associated with the use of hearing protection during noisy activities.

Understanding the attitudes and practices of college students regarding noise exposure may provide guidance in the development of policies and program interventions that would assist in reducing noise exposure and risk to NIHL.

Methods

Survey instrument

The survey utilized in this study included 6 demographic items, 19 items on attitudes toward noise, 5 items on hearing symptoms, and 14 items on noise exposure and hearing protection use. The demographic questions focused on age, gender, race, university class standing, residence type, and fraternity or sorority membership.

Nineteen items related to the attitudes toward noise were adopted from the Youth Attitudes to Noise Scale (YANS) and were assessed using a five-point Likert scale: 1 = Totally agree, 2 = Partially agree, 3 = Neither, 4 = Partially disagree, and 5 = Totally disagree.[15] YANS included various types of common sounds that young people may encounter and was subdivided into four factors:

Eight items dealing attitude toward noise associated with elements of youth culture (e.g., discos);

Three items dealing with attitudes toward the ability to concentrate in noisy environments;

Four items dealing with attitudes toward daily noises (e.g., traffic); and

Four items dealing with attitudes toward influencing the sound environment.

The mean scores for the entire YANS and on the four different factors were assessed for a negative, neutral, or positive attitude toward noise. A score in the lower quartile (0.00-2.47) indicates a negative attitude toward noise or antinoise attitude (i.e., noise is perceived as harmful and to be avoided) while a score in the upper quartile (3.00-5.00) indicates a positive or pronoise attitude (i.e., noise is not perceived as dangerous). A score in the two middle quartiles (2.48-2.99) indicates a neutral attitude wherein one does not care or is unaware of the possible consequences of loud noise.[26]

Hearing symptom items, as adapted from the Hearing Symptom Description (HSD) scale,[30] pertained to experiences related to temporary tinnitus (i.e., temporary buzzing or ringing in the ears that lasted longer than 24 h), permanent tinnitus (i.e., permanent buzzing or ringing in the head or ears all the time), noise sensitivity (i.e., being more sensitive to noise than others), hearing loss, and ear pain after loud noise exposure. Lastly, items on noise exposure, which were adapted from the Adolescents’ Habits and Use of Hearing Protection (AAH) scale,[31] focused on participation in noisy activities (e.g., attending rock concerts, discos/dances, or sporting events, shooting, playing in a band, use of noisy tools) and use of hearing protection at these activities.

Sample and administration

Participants were recruited among the currently enrolled undergraduate students attending East Carolina University (ECU) in Greenville, North Carolina, USA, during the spring semester in 2014. The study received approval from the ECU Institutional Review Board (Approval # UMCIRB 14-000346). Participants were invited to complete an online questionnaire created using Qualtrics (Provo, UT, USA). Informed consent was obtained through the survey. The survey was administered to all students enrolled in a personal health course [i.e., Health (HLTH) 1000]. Students were invited via email to participate at their convenience, and were informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous. Consequently, students who took the survey received extra credit by presenting the course instructor a “receipt” that was produced when responses were submitted. The responses were reviewed for completeness during data cleaning. Students who failed to complete the YANS section were removed from the study, resulting in 2,151 participants included in the study out of the 2,331 students enrolled in the course (92.3% participation rate).

Data analysis

The frequencies and percentages for categorical measures were summarized while the means and standard deviations for continuous measures were determined. Pearson chi-square tests were used to evaluate gender differences among hearing symptoms, noisy activities, and hearing protection use; evaluate the relationship between hearing symptoms and noisy activities and other demographic variables; and evaluate the relationship between the use of hearing protection and noisy activities and other demographic variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used in calculating adjusted odds ratios (AORs) to evaluate the effect of several predictor variables on hearing symptom occurrence. Variables that were statistically significant in the crude analysis and chi-square analysis were used in the multivariate logistic regression to determine the strongest predictors of hearing symptom occurrence after controlling other independent variables. Nonpaired t-tests and ANOVA were used to compare mean YANS scores between both the genders, hearing symptom occurrence and hearing protection use, and by age, race, class standing, and residence type. Bivariate correlations were calculated between the four factors and the entire YANS. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20, SPSS Institute, Chicago, IL, USA was used to analyze the data. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Study participants

Of the 2,151 students participating in the study, 1,390 were women (64.6%) and 750 were men (34.9%) [Table 1]. The average of age of the participants was 19.06 ± 1.50 years, ranging from 18 years to 30 years, with most of the respondents at aged 19 years (43.1%) and 18 years (28.9%). The participants were predominantly non-Hispanic whites (67.3%), freshmen (79.0%), and residing in campus residence halls (79.9%).

Table 1.

Description of college student participants (N = 2,151)

| Characteristic | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 750 | 34.9 |

| Female | 1,390 | 64.6 |

| Other | 8 | 0.4 |

| No response | 3 | 0.1 |

| Age | ||

| 18 years | 621 | 28.9 |

| 19 years | 928 | 43.1 |

| 20 years | 133 | 6.2 |

| 21 years | 69 | 3.2 |

| 22 years and above | 82 | 3.8 |

| No response | 318 | 14.8 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1448 | 67.3 |

| Black | 415 | 19.3 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 124 | 5.8 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 83 | 3.9 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 27 | 1.3 |

| Other | 51 | 2.4 |

| No response | 3 | 0.1 |

| Academic class standing | ||

| Freshman | 1700 | 79.0 |

| Sophomore | 270 | 12.6 |

| Junior | 136 | 6.3 |

| Senior | 38 | 1.8 |

| Other | 3 | 0.1 |

| No response | 4 | 0.2 |

| Residence type | ||

| Campus residence hall | 1,718 | 79.9 |

| Fraternity or sorority house | 9 | 0.4 |

| Off-campus housing | 354 | 16.5 |

| Parent/guardian’s home | 63 | 2.9 |

| No response | 7 | 0.3 |

Attitude toward noise

Table 2 presents the correlation between the entire YANS and four factors, along with the Cronbach's alpha to establish reliability. The correlation coefficients between factors ranged from 0.23 to 0.71 while those between the factors and entire YANS ranged from 0.63 to 0.88. In this study, Cronbach's alpha for the entire scale was α = 0.845, which was within the acceptable value (≥0.7).

Table 2.

Correlations between the factors and the entire Youth Attitude to Noise Scale (YANS), and their Cronbach’s alpha (N = 2,151)

| Factor | F1: Youth culture | F2: Concentration | F3: Daily noise | F4: Intent to influence | Entire YANS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1: Youth culture | — | ||||

| F2: Concentration | 0.402* | — | |||

| F3: Daily noise | 0.453* | 0.415* | — | ||

| F4: Intent to influence | 0.706* | 0.230* | 0.422* | — | |

| Entire YANS | 0.880* | 0.630* | 0.746* | 0.774* | — |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.649 | 0.673 | 0.826 | 0.614 | 0.845 |

*P < 0.01 (two-tailed)

The first specific aim of this study is addressed by the following results in this section. Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations for the entire YANS and the four factors. The entire YANS and factors 1, 2, and 4 showed neutral attitudes for college students toward noise while factor 3 showed antinoise attitude. This indicated that the college students were more bothered by common noises in their daily environment (factor 3) but were more tolerant with noise related to youth culture (factor 1). The average scores for the entire YANS and all factors between men and women were not significantly different [Table 3].

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations (SDs) for the entire Youth Attitude to Noise Scale (YANS) and the four factors of college student participants by gendera (N = 2,151)

| Factor | Total (N = 2,151)b | Men (N = 750)b | Women (N = 1390)b | P valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Entire YANS | 2.76 | 0.55 | 2.75 | 0.60 | 2.76 | 0.52 | 0.63 |

| F1: Youth culture | 2.90 | 0.58 | 2.88 | 0.63 | 2.91 | 0.54 | 0.19 |

| F2: Concentration | 2.88 | 0.89 | 2.85 | 0.89 | 2.89 | 0.89 | 0.25 |

| F3: Daily noise | 2.41 | 0.86 | 2.44 | 0.83 | 2.38 | 0.87 | 0.14 |

| F4: Intent to influence | 2.72 | 0.69 | 2.71 | 0.72 | 2.73 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

aGender was identified as “other” for 8 students, and missing for 3 students, bNumbers do not add to the total value because of missing and “other” responses, cSignificance between gender, P <0.05, YANS score — antinoise: 0.00-2.47, neutral: 2.48-2.99, pronoise: 3.00-5.00

Except for factor 2 (concentration), there is a decreasing trend in mean scores starting from the age of 20 years though the attitude remains neutral (factors 1 and 4) or antinoise (factor 3). For factor 2, there is an abrupt increase in mean score to pronoise attitude in the age <22 years. Among the YANS factors, only factor 4 (intent to influence) showed a significant difference (P = 0.02) in mean scores by age. Mean scores were significantly different by race (P < 0.01) only for factor 2 (concentration), with American Indian/Alaskan native having the lowest average score (2.58 ± 0.79) and non-Hispanic whites having the highest score (2.92 ± 0.89). All mean YANS scores by residence type showed a significance difference (P < 0.01 to 0.04) except for factor 4 (P = 0.30), with fraternity/ sorority house generally having the lowest scores across the factors. Students living in fraternity/ sorority houses had the lowest average entire YANS score (2.40 ± 1.28) while campus residents had the highest (2.77 ± 0.55). Differences in mean scores by class standing were not statistically significant (P = 0.24 to 0.48).

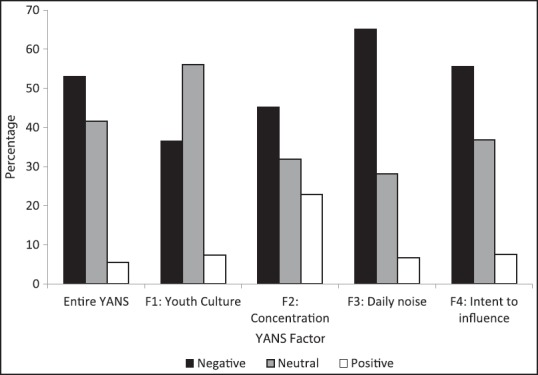

Students with negative or antinoise attitudes comprised the highest percentages (45.2-65.1%) for the entire YANS and factors 2, 3, and 4. However, the highest percentage (56.1%) for factor 1 (youth culture) comprises students with neutral attitude toward noise [Figure 1]. Positive or pronoise attitude consistently had the smallest percentage (5.5-22.9%) for all YANS factors.

Figure 1.

Percentage of attitudes toward noise category by YANS Factor (N = 2151)

Hearing symptoms

Self-reported noise-related hearing symptoms among college students were determined to address the second specific aim of this study. Among the participants, 852 (39.6%) experienced at least one hearing symptom, out of whom 310 (36.4%) were males and 538 (63.1%) were females. However, the percentage of men (41.3%) who had experienced at least one hearing symptom was not significantly different from that of women (38.7%) (P = 0.24). Table 4 lists reported hearing symptoms that may be caused or aggravated by noise exposure, with pain in the ears as the most reported (22.5%) followed by more sensitivity to noise compared to other people (20.8%). Higher percentages of men experienced each of the hearing symptoms compared to women (P < 0.01 to P = 0.02) except for noise sensitivity (22.3% in women, 18.1 in men, P = 0.02).

Table 4.

Reported hearing symptoms among college students by gendera (N = 2,151)

| Hearing symptom | Gender | P value | Total (N = 2,151)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (N = 750)b | Female (N = 1,390)b | ||||||

| n | %c | n | %c | n | %c | ||

| Ear pain after noise exposure | 192 | 25.6 | 291 | 20.9 | 0.02 | 485 | 22.5 |

| Noise sensitivity | 136 | 18.1 | 310 | 22.3 | 0.02 | 448 | 20.8 |

| Temporary tinnitus | 136 | 18.1 | 148 | 10.6 | <0.01 | 284 | 13.2 |

| Permanent tinnitus | 43 | 5.7 | 47 | 3.4 | 0.01 | 91 | 4.2 |

| Self-reported hearing loss | 79 | 10.5 | 93 | 6.7 | <0.01 | 173 | 8.0 |

aGender was identified as “other” for 8 students, and missing for 3 students, bNumbers do not add to the total value because of missing and “other” responses, cPercentage within gender

The highest percentages of those with at least one hearing symptom were among college students who were 21-years-old (50.7%), white (43.1%), of junior standing (50.7%), and lived in off-campus housing (48.0%). Age, race, class standing, and residence type showed significant relationships with having a hearing symptom (P ≤ 0.01 to P = 0.02). For all hearing symptoms, the age that reported the highest percentage of affected individuals was 21 years: Temporary tinnitus −23.2%; permanent tinnitus −7.2%; noise sensitivity −27.5%; hearing loss −15.9%; and ear pain −29.0%. Only the relationships between age and temporary tinnitus (χ2 =17.99, P < 0.01) and hearing loss (χ2 =12.86, P = 0.01) are statistically significant.

For factors 1 and 4, the mean scores of students who reportedly experienced any of the hearing symptoms are significantly lower than those who did not [Table 5] and although the attitude generally stayed neutral, this indicates more antinoise attitudes among those with hearing symptoms. However, the mean entire YANS score of students who reported experiencing ear pain, permanent tinnitus, and hearing loss compared to those who did not were also significantly lower (P < 0.01). In contrast, the mean YANS scores for factors 2 and 3 of those who reported experiencing noise sensitivity and temporary tinnitus were significantly higher (P < 0.01 to 0.03) than those who did not [Table 5]. Moreover, the percentages of students with at least one hearing symptoms between those with overall antinoise (40.8%) and neutral (39.3%) attitudes were not significantly different (P = 0.49).

Table 5.

Mean and standard deviations (SDs) for the entire Youth Attitude to Noise Scale (YANS) and the four factors of college student participants by reported hearing symptoms (N = 2,151)

| YANS factor | With hearing symptom | Mean | SD | t+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire YANS | ||||

| Ear pain | Yes | 2.69 | 0.50 | −3.11** |

| No | 2.78 | 0.56 | ||

| Noise sensitivity | Yes | 2.72 | 0.55 | −1.74 |

| No | 2.77 | 0.55 | ||

| Temporary tinnitus | Yes | 2.71 | 0.61 | −1.51 |

| No | 2.77 | 0.53 | ||

| Permanent tinnitus | Yes | 2.52 | 0.81 | −4.2** |

| No | 2.77 | 0.53 | ||

| Hearing loss | Yes | 2.64 | 0.69 | −2.88** |

| No | 2.77 | 0.53 | ||

| Factor 1 | ||||

| Ear pain | Yes | 2.82 | 0.56 | −3.73** |

| No | 2.93 | 0.57 | ||

| Noise sensitivity | Yes | 2.79 | 0.58 | −4.83** |

| No | 2.93 | 0.57 | ||

| Temporary tinnitus | Yes | 2.82 | 0.65 | −2.77** |

| No | 2.92 | 0.56 | ||

| Permanent tinnitus | Yes | 2.59 | 0.83 | −5.47** |

| No | 2.92 | 0.55 | ||

| Hearing loss | Yes | 2.74 | 0.73 | −3.88** |

| No | 2.92 | 0.55 | ||

| Factor 2 | ||||

| Ear pain | Yes | 2.89 | 0.91 | 0.28 |

| No | 2.88 | 0.88 | ||

| Noise sensitivity | Yes | 3.06 | 0.97 | 4.84** |

| No | 2.83 | 0.86 | ||

| Temporary tinnitus | Yes | 2.79 | 0.91 | −1.93 |

| No | 2.90 | 0.88 | ||

| Permanent tinnitus | Yes | 2.58 | 1.01 | −3.37** |

| No | 2.89 | 0.88 | ||

| Hearing loss | Yes | 2.74 | 0.95 | −2.12* |

| No | 2.89 | 0.88 | ||

| Factor 3 | ||||

| Ear pain | Yes | 2.39 | 0.78 | −0.60 |

| No | 2.41 | 0.88 | ||

| Noise sensitivity | Yes | 2.50 | 0.81 | 2.62** |

| No | 2.38 | 0.87 | ||

| Temporary tinnitus | Yes | 2.51 | 0.86 | 2.23* |

| No | 2.39 | 0.86 | ||

| Permanent tinnitus | Yes | 2.42 | 0.92 | 0.16 |

| No | 2.41 | 0.86 | ||

| Hearing loss | Yes | 2.47 | 0.93 | 1.04 |

| No | 2.40 | 0.85 | ||

| Factor 4 | ||||

| Ear pain | Yes | 2.59 | 0.67 | −5.03** |

| No | 2.77 | 0.69 | ||

| Noise sensitivity | Yes | 2.54 | 0.71 | −6.54** |

| No | 2.77 | 0.67 | ||

| Temporary tinnitus | Yes | 2.65 | 0.74 | −2.02* |

| No | 2.74 | 0.68 | ||

| Permanent tinnitus | Yes | 2.46 | 0.89 | −3.70** |

| No | 2.74 | 0.68 | ||

| Hearing loss | Yes | 2.54 | 0.81 | −3.62** |

| No | 2.74 | 0.67 |

+Nonpaired t-test, significance (two-tailed), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Participation in noisy activities

The third specific aim of this study was addressed by determining the noise activities and locations in which college students were involved. Among the participants, 1,780 (82.8%) were involved in at least one noisy activity, out of whom 1,100 (61.8%) were women and 674 (37.9%) were men. However, the percentage of men (89.9%) who participated in at least one noisy activity was significantly higher than that of women (79.1%) (P < 0.01). Table 6 shows the percentage of students who participated in noisy activities. More than half the participants reported having participated in sporting events (59.7%) and discos/dances (55.4%). Playing in a band was reported to be the least participated noisy activity (9.8%). Percentages of men participating in each of the noisy activities were significantly higher compared to women (P < 0.01 to P = 0.03) except for discos/dances in which the percentage of women are significantly higher, though marginally (P = 0.048).

Table 6.

Reported participation in noisy activities among college students by gendera (N = 2,151)

| Noisy activity | Total (N = 2,151)b (%) | Male (N = 750)b (%) | Female (N = 1,390) (%) | P-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sporting event | 1,285 (59.7) | 563 (75.1) | 720 (51.8) | <0.01 |

| Discos/dances | 1,191 (55.4) | 389 (51.9) | 797 (57.3) | 0.05 |

| Attending rock concerts | 918 (42.7) | 341 (45.5) | 574 (41.3) | 0.03 |

| Lawn mowing | 824 (38.3) | 516 (68.8) | 306 (22.0) | <0.01 |

| Shooting/use of firearms | 697 (32.4) | 374 (49.9) | 321 (23.1) | <0.01 |

| Using noisy tools | 629 (29.2) | 381 (50.8) | 246 (17.7) | <0.01 |

| Playing in a band | 211 (9.8) | 122 (16.3) | 88 (6.3) | <0.01 |

aGender was identified as “other” for 8 students, and missing for 3 students, bNumbers do not add to the total value because of missing and “other” responses, cGender difference, P < 0.05

Among the noisy activities, the largest percentage of students with at least one reported hearing symptom was involved in playing in a band (60.7%) followed by using noisy tools (49.8%), shooting/use of firearms (47.1%), attending rock concerts (46.1%), lawn mowing (45.3%), discos/dances (43.2%), and sporting events (42.6%). However, among those with at least one hearing symptom, 64.2% participated in sporting events, 60.3% in discos/dances, and 49.6% in rock concerts. When adjusted for age and gender, having at least one hearing symptom was associated with shooting/use of firearms (AOR = 1.55, P < 0.01), playing in a band (AOR = 2.28, P < 0.01), sporting events (AOR = 1.34, P < 0.01), attending rock concerts (AOR = 1.56, P < 0.01), discos/dances (AOR= 1.37, P < 0.01), and using noisy tools (AOR = 1.94, P < 0.01). The highest percentages of students with ear pain (69.9%), hearing loss (65.3%), permanent tinnitus (70.3%), and noise sensitivity (63.2%) were involved in sporting events and the highest percentages of students with temporary tinnitus (65.8%) were involved in discos/dances.

Use of hearing protection

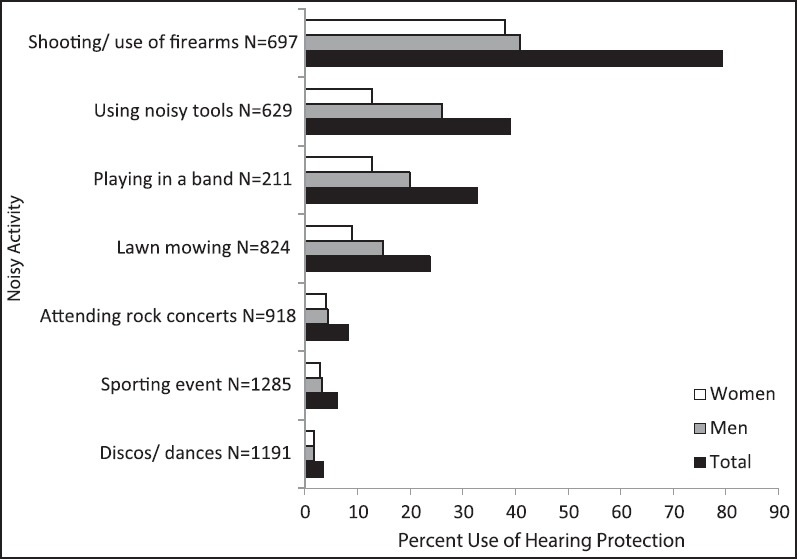

In this study, the use of hearing protection was considered at any frequency (i.e., always or sometimes). The fourth specific aim of the study was addressed by determining the factors associated with hearing protection use during noisy activities. Among the 1,780 participants involved in at least one noisy activity, 730 (41.0%) reported to have used hearing protection during the noisy activity, with the percentage of men (55.9%) reporting its use being significantly higher than that of women (31.8%) (P < 0.01). The majority of those who reported using hearing protection in any of the noise activities were 19-years-old (42.6%), non-Hispanic white (80.1%), and freshmen (77.6%). A relationship was observed between the use of hearing protection and race (χ2 =98.57, P < 0.01) but not with age (χ2 = 6.37, P = 0.17) and class standing (χ2 = 3.27, P = 0.51).

Figure 2 shows the percentage of students who reported the use of hearing protection for each noisy activity and their gender. The largest percentage of students who reported having used hearing protection was involved in shooting or use of firearms (79.2%) followed by the use of noisy tools (39.3%) and playing in a band (32.7%) [Figure 2]. The least use of hearing protection was reported in discos or dances (3.4%). The higher percentages of men who reported using hearing protection participated in rock concerts (P < 0.01), discos/dances (P = 0.01), and used noisy tools (P = 0.02) compared to women. However, the percentage of women who used hearing protection during the shooting of firearms was significantly higher than that of men (P = 0.03)

Figure 2.

Percentage of reported hearing protection use by noisy activity and gender

The reported use of hearing protection was significantly higher among those with at least one hearing symptom (47.6%) compared to those with no hearing symptom (36.2%) (P < 0.01). However, the use of hearing protection has a significantly stronger relationship with temporary tinnitus (χ2 = 43.5, P < 0.01), permanent tinnitus (χ2 = 31.1, P < 0.01), hearing loss (χ2 = 30.5, P < 0.01), and ear pain (χ2 = 36.7, P < 0.01) than with noise sensitivity (χ2 = 3.8, P = 0.03).

For the entire YANS and factor 4, the mean scores of those who reported the use of hearing protection in all the specific noise activities were significantly lower (P < 0.01 to 0.03) than those who did not [Table 7], thus leaning toward the antinoise attitude. Mean scores of the other YANS factors of those who used hearing protection were also significantly lower than those who did not in the following activities: shooting or use of firearms (factor 3), playing in a band (factors 1-3), sporting event (factors 1-3), lawn mowing (factors 1-2), attending rock concerts (factors 1-2), discos/dances (factors 1-2), and using noisy tools (factor 1). Generally, the mean scores (entire YANS and certain factors) of those who reported hearing protection use in the following noisy activities were classified under the antinoise attitude while those who did not had mean score were classified under the neutral attitude: playing in a band (entire YANS, factors 3 and 4), sporting event (entire YANS, factors 2 and 4), attending rock concerts (entire YANS, factor 4), and discos/dances (entire YANS, factors 1, 2 and 4). The percentage of students who used hearing protection in any noise activity among those overall antinoise attitude (43.7%) was significantly higher (P = 0.02) than among those with neutral attitude (37.9%).

Table 7.

Mean and standard deviations (SDs) for the entire Youth Attitude to Noise Scale (YANS) and the four factors of college student participants by the use of hearing protection in noisy activities

| YANS factor | HPD† Use | Mean | SD | t+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire YANS | ||||

| Shooting/use of firearms | Yes | 2.70 | 0.58 | −2.25* |

| No | 2.82 | 0.61 | ||

| Playing in a band | Yes | 2.44 | 0.85 | −3.32** |

| No | 2.77 | 0.58 | ||

| Sporting event | Yes | 2.39 | 0.79 | −6.38** |

| No | 2.77 | 0.49 | ||

| Lawn mowing | Yes | 2.58 | 0.59 | −4.50** |

| No | 2.79 | 0.53 | ||

| Attending rock concerts | Yes | 2.43 | 0.76 | −5.09** |

| No | 2.75 | 0.50 | ||

| Discos/dances | Yes | 2.21 | 0.93 | −7.02** |

| No | 2.78 | 0.49 | ||

| Using noisy tools | Yes | 2.62 | 0.61 | −3.45** |

| No | 2.77 | 0.52 | ||

| Factor 1 | ||||

| Shooting/use of firearms | Yes | 2.83 | 0.60 | −1.74 |

| No | 2.93 | 0.64 | ||

| Playing in a band | Yes | 2.54 | 0.89 | −3.47** |

| No | 2.90 | 0.57 | ||

| Sporting event | Yes | 2.48 | 0.86 | −7.07** |

| No | 2.93 | 0.52 | ||

| Lawn mowing | Yes | 2.71 | 0.65 | −5.37** |

| No | 2.96 | 0.54 | ||

| Attending rock concerts | Yes | 2.55 | 0.84 | −5.64** |

| No | 2.93 | 0.53 | ||

| Discos/dances | Yes | 2.25 | 0.95 | −8.38** |

| No | 2.95 | 0.51 | ||

| Using noisy tools | Yes | 2.73 | 0.66 | −4.37** |

| No | 2.94 | 0.54 | ||

| Factor 2 | ||||

| Shooting/use of firearms | Yes | 2.82 | 0.92 | −0.05 |

| No | 2.82 | 0.87 | ||

| Playing in a band | Yes | 2.48 | 1.05 | −2.26* |

| No | 2.80 | 0.92 | ||

| Sporting event | Yes | 2.44 | 0.96 | −4.42** |

| No | 2.90 | 0.87 | ||

| Lawn mowing | Yes | 2.73 | 0.93 | −1.97* |

| No | 2.87 | 0.87 | ||

| Attending rock concerts | Yes | 2.56 | 0.93 | −2.61** |

| No | 2.84 | 0.88 | ||

| Discos/dances | Yes | 2.32 | 1.05 | −4.08** |

| No | 2.89 | 0.87 | ||

| Using noisy tools | Yes | 2.74 | 0.98 | −1.05 |

| No | 2.82 | 0.89 | ||

| Factor 3 | ||||

| Shooting/use of firearms | Yes | 2.36 | 0.84 | −2.66** |

| No | 2.57 | 0.87 | ||

| Playing in a band | Yes | 2.21 | 0.93 | −2.06* |

| No | 2.48 | 0.88 | ||

| Sporting event | Yes | 2.17 | 0.91 | −2.34* |

| No | 2.40 | 0.82 | ||

| Lawn mowing | Yes | 2.29 | 0.79 | −1.78 |

| No | 2.41 | 0.83 | ||

| Attending rock concerts | Yes | 2.21 | 0.83 | −1.39 |

| No | 2.35 | 0.84 | ||

| Discos/dances | Yes | 2.16 | 0.96 | −1.53 |

| No | 2.37 | 0.86 | ||

| Using noisy tools | Yes | 2.31 | 0.81 | −1.20 |

| No | 2.40 | 0.86 | ||

| Factor 4 | ||||

| Shooting/use of firearms | Yes | 2.69 | 0.69 | −2.72** |

| No | 2.87 | 0.69 | ||

| Playing in a band | Yes | 2.43 | 0.95 | −3.01** |

| No | 2.78 | 0.70 | ||

| Sporting event | Yes | 2.37 | 0.84 | −4.76** |

| No | 2.74 | 0.64 | ||

| Lawn mowing | Yes | 2.54 | 0.69 | −4.17** |

| No | 2.77 | 0.65 | ||

| Attending rock concerts | Yes | 2.31 | 0.82 | −5.08** |

| No | 2.71 | 0.65 | ||

| Discos/dances | Yes | 2.11 | 0.90 | −6.18** |

| No | 2.75 | 0.65 | ||

| Using noisy tools | Yes | 2.59 | 0.72 | −3.40** |

| No | 2.78 | 0.64 |

+Nonpaired t-test, significance (two-tailed), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, †HPD: Hearing protection device

Discussion

The most commonly reported noise activities among student participants were sporting events (59.7%), discos/dances (55.4%), and attending rock concerts (42.7%), which are all considered as common youth activities followed by lawn mowing (38.3%) and use of firearms (32.4%). Similarly, in a survey of college students in a West Virginia university by Lass et al.,[32] the most frequently attended leisure activities were dances (69.9%) and rock concerts (63.5%) while the most frequently used equipment included lawn mowers (47.0%) and firearms (11.3%).

Among those with at least one reported hearing symptom, at least half participated in sporting events, discos/dances, and rock concerts, indicating that these activities may be significant sources of excessive noise exposure for this young population. Participation in sporting events was found to have the highest percentage of students (≥63%) with ear pain, hearing loss, permanent tinnitus, and noise sensitivity. Attending discos/dances had the highest percentage (65.8%) of those with temporary tinnitus, which was similar to the findings of Widen et al.[26] wherein temporary tinnitus was mostly reported among those attending discotheques and concerts.

Collegiate football is one of the most popular academic sporting events and is a traditional part of the southern culture in the southern US. Participation in these events is considered to be a serious matter to the extent that it is compared to “having religious experiences.”[33] Thus, it may be one of the most significant exposures of college students to noise. Both workers and spectators in football games are potentially exposed to hazardous noise from the crowd, public address system, and team bands.[34] A study by Engard et al.[34] in outdoor football stadiums [one National Football League (NFL) and two college stadiums] found that 96% of the fans sampled were overexposed to noise levels according to the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) criteria (≥85 dBA, 3 dB exchange rate), with mean maximum personal noise exposure level of 116-120 dB. Moreover, Rawool[35] reported that noise levels at a football game ranged from 68.3 dBA to 124.8 dBA with peak levels at 138.6 dB but noise exposures near the cheering and band sections are expected to be much higher. Recently, an NFL stadium in Kansas, MO, USA claimed the Guinness World Record for “the loudest stadium in the world,” with a noise level reading of 142.2 dB.[36] Other sporting events apart from football games were also reported to expose people in the arena to noise levels with a range of 81-104 dBA during hockey games[37,38] and 79-90 dBA in basketball games.[39] Noise exposure data during these sporting events may provide baseline information for further research on noise control in these venues.

Hearing symptoms, attitudes, and hearing protection use

Generally, those with more severe hearing symptoms (ear pain, permanent tinnitus, and hearing loss) have more antinoise attitudes compared to those who do not, which is consistent with previous studies.[23,26] Such attitudes may have developed because of the impact of their severe hearing symptoms to their quality of life. This consequently may lead to hearing protection use because of their continued concern about their hearing. On the contrary, in certain YANS factors, those who reported less severe hearing symptoms (noise sensitivity, temporary tinnitus) have more pronoise attitudes. This may indicate that these students are engaged in noisy activities in which hearing symptoms start to manifest and thus less severe, but they have not yet perceived the extent of the harm that noise exposure can cause to their hearing. Similar findings were reported by Widen et al.[26]

This study showed that those with at least one hearing symptom reported the use of hearing protection more than those with no hearing symptom. Similarly, adolescents and young adults who reported hearing symptoms, such as tinnitus and noise sensitivity, were found to protect their hearing more compared to those without the symptoms.[15,16,26,29] Moreover, students experiencing more severe hearing symptoms (i.e., ear pain, hearing loss, and tinnitus) are more likely to use hearing protection than those with less severe ones (i.e., noise sensitivity). An explanation for this is that individuals with more severe hearing symptoms have developed more concern about protecting what is left of their hearing and therefore, use hearing protection more. These results support the Health Belief Model, which states that a trigger, which is a negative health outcome (i.e., hearing symptom), could prompt a person to adopt more health-oriented behaviors (i.e., use of hearing protection).[40] This suggests that knowledge of the harmful effects of noise on hearing may help in increasing the use of hearing protection.[16]

The reported use of hearing protection was shown to be low in discos/dances, rock concerts, and sporting events while it was found to be higher during the use of firearms and noisy tools and in lawn mowing, which was similarly found in previous studies.[4,25,26] In this study, those who reported the use of hearing protection in any noise activity had more antinoise attitudes than those who did not. This finding is supported by the Theory of Planned Behavior, which states that an individual's intention to carry out a behavior is dependent on his or her attitude regarding the behavior, subjective norms (i.e., perception of social pressures), and perceived behavioral control (i.e., personal belief of one's ability to perform a behavior based on the presence of factors).[41] Thus, attitude toward noise was shown to be an important influence on hearing protection use. This study generally showed that those who reported hearing protection use when attending sporting events, rock concerts and discos/ dances, and playing in a band had antinoise attitudes while those who did not had neutral attitudes. In contrast, those who reported hearing protection use when using firearms, noisy tools, and lawn mowers and those who did not had both neutral attitudes though the hearing protection users’ attitudes leaned more toward antinoise. This implies that it would take an antinoise attitude to make a young adult use hearing protection in youth social events or leisure activities where loud music and cheering is acceptable and even desired and makes such an event or activity more enjoyable and where hearing protection use may be perceived as awkward. Moreover, having a neutral attitude toward noise is sufficient for one to use hearing protection in activities such as lawn mowing and use of noise tools and firearms, and does not require an antinoise attitude because hearing protection use in these activities is more common and acceptable and the loud noise produced is most likely to be unwanted. Attitudes measured by factor 1, which is associated with elements of youth culture (i.e., sound level at discos, dances, concerts, and sporting events) was previously shown to contribute significantly to the use of hearing protection among young people. Widen et al.[23] reported that college students with antinoise attitudes toward youth culture noise are more likely to report the use of hearing protection compared to those with pronoise attitudes but having a neutral attitude did not increase the odds of hearing protection use. Therefore, attitudes and self-experienced hearing symptoms are important factors for understanding and influencing the use of hearing protection as a preventive behavior relation to hearing risks, as concluded in a previous study.[26]

Noise exposure reduction strategies for college students

Data on noise exposure and hearing symptom prevalence support the need for further research on appropriate noise reduction and hearing conservation methods that will be effective for the young adult population. Public health interventions such as education, training, audiometric testing, exposure assessment, hearing protection, and noise control were identified as components of occupational hearing conservation that may be adapted to the needs of this specific young population.[12]

Educating the youth to prevent noise exposure and hearing loss is an important part of a hearing conservation program. Desired outcomes of such educational efforts may include noise exposure reduction among the youth by limiting participation in noisy activities and the use of hearing protection when participating in such activities. The aim of youth education should be the improvement of both their knowledge and attitude that would result in preventive behaviors related to hearing risks. Chung et al.[4] have shown that hearing loss is considered to be a low priority among health issues by the young population compared to other health issues, such as sexually transmitted diseases, alcohol and drug use, depression, and smoking, which may be due to the lack of awareness about the extent of noise effects on their hearing and the impact of hearing loss to their future quality of life. Lass et al.[32] reported some deficiencies in the knowledge of college students on the mechanism of normal hearing and hearing loss, which demands improved educational efforts to increase college students’ knowledge of hearing health. However, increased knowledge does not always result in the performance of the intended behavior. A few studies[28,32] reported that a large majority of surveyed college students were aware that loud noise could cause permanent hearing loss and that NIHL could be prevented by the use of hearing protection. Despite such knowledge, a majority of the students never used hearing protection. Moreover, a study[16] found that a majority of the adolescents (74%) considered sound levels at discotheques as posing a risk to their hearing but only 20% reported hearing protection use. The minimal use of hearing protection among the youth is speculated to be due to lack of knowledge on the effects of noise exposure, attitudes, social acceptance, or a combination of these,[25] and addressing each of these factors may be necessary to improve hearing protection use as part of a hearing conservation program. A significant amount of education at various levels in society is crucial in modifying individual behaviors such as hearing protective behavior.[4] Thus, hearing conservation strategies for college students must involve various stakeholders including the college students, parents, health service providers, universities/colleges, and the government. Parents were the most likely group to recommend the use of earplugs among adolescents and young adults followed by physicians but only a few received education related to hearing loss at school.[4] Improving education in universities on hearing health is one important issue that may be improved.

Another hearing conservation strategy for college students and other young adults is making hearing protection available during noisy youth activities. Wearing of earplugs by live music concert attendees has been recommended.[42] To encourage this behavior, providing earplugs and NIHL information (e.g., in posters, fan guides, and pamphlets) that suggests hearing protection use at the entrance of concerts and sporting venues was advised.[16,34,39] In April 2014, Minneapolis, MN, USA took hearing protection availability to a higher level by passing a new provision that required clubs, bars, and restaurants to provide free earplugs to patrons; some other states were also expected to follow.[43] However, hearing protection being readily available does not always result in its use. Bogoch et al.[16] reported that less than half of rock concert attendees said they would wear earplugs if they were provided for free at the door, and that being concerned about the appearance of hearing protection may predict the outcome of wanting to use these free earplugs. Thus, the acceptability of hearing protection use is important to be addressed through positive changes in attitude and subjective norms. As an approach, developing new colors, styles, and packaging of earplugs through collaboration is now being explored to make them more acceptable for use.[43] In particular. in activities that involve listening to music, one reason behind college students not using hearing protection is the difficulty in hearing the music.[29] Thus, providing hearing protection with a flat attenuation across the frequency range may also encourage its use because the quality of music is less affected while being protected from excessively loud music.[16] The advocacy of hearing protection use by well-known musicians and athletes through advertisements may also help in encouraging hearing protection use in youth events since social influences such as peers, public role models, and the television may affect behavior regarding hearing protection use.[4,16]

The role of universities and colleges in hearing conservation

Educational programs on hearing conservation were advocated to be started early in school (e.g., elementary and high schools).[12,44,45] The positive impact of these programs on behavior modification of school-aged children has been demonstrated.[46] Such efforts may be strengthened if hearing conservation programs are continued in universities and colleges. A need for more educational efforts on hearing health and hearing loss on college campuses has been identified.[32] These efforts entail the conduct of hearing conservation programs that will empower students with proper information on hearing, hearing loss, and hearing protection at home, in school, and at recreational events. Because of the significant number of college students exposed to noise, the inclusion of a topic on noise and hearing conservation within a required course (e.g. health course) in the academic curriculum is strongly advocated. In this way, all college students will be provided the basic information about hearing health. It is also recommended that hearing health be promoted by student health services of universities and colleges through information dissemination using posters and flyers, and providing advice. Subtopics that may be included are:

The normal auditory mechanism;

Types of hearing loss and their causes;

Noise and its effects on hearing;

Warning signs of NIHL; and

Specific recommendations for NIHL prevention.[30]

It has been demonstrated that having self-experienced hearing symptoms likely increases the use of hearing protection. However, our higher aim is to encourage hearing protection use before individuals start damaging their hearing. Emphasizing the severity of the effects of excessive noise on hearing must be done during educational efforts to relay such message, which may entail allowing individuals to experience how tinnitus and/or NIHL sounds like and how it affects the understanding of speech and appreciation of music. Such a strategy may serve as an important trigger to change attitudes from pronoise into antinoise before the individuals actually get hearing symptoms.[26]

Formats for the presentation of hearing health information have been suggested including formal lectures, fact sheet handouts or brochures, posters, exhibits, films, and classroom discussions.[32] Using any presentation format, college students must also be made aware of reputable online resources for information on noise exposure reduction. Teens spend a considerable amount of web time visiting health sites and their personal behavior may change because of the health information they obtain online.[47] Considering this, the full potential of the world wide web as a powerful communication medium must be utilized by health educators and researchers. Examples of websites that are dedicated to NIHL awareness and prevention are WISE EARS!Ò,[48] Hearing Education and Awareness for Rockers or H.E.A.R. (http://www.hearnet.com) and It's a Noisy Planet (http://www.noisyplanet.nidcd.nih.gov/Pages/Default.aspx). WISE EARS!Ò, launched by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) and the National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH), is a popular national public education campaign that aims to increase awareness about NIHL among various audiences (e.g., parents, teachers, health professionals, children, entertainment industry, and the general public) and to motivate to take action against NIHL.

Another important component identified for increasing college students’ awareness on hearing health is student involvement.[32] This may entail involvement of student groups from degree programs (e.g. Speech and Hearing Sciences, Communication Sciences and Disorders, Environmental Health, and Public Health) or student chapters of organizations (e.g., National Student Speech Language Hearing Association and NC Public Health Association) related speech, hearing, and public health. Student activities may include developing informational fact sheets for distribution to the student body; arranging the sale of earplugs at sporting events or music concerts on campus; and establishing noise limitations for all on-campus concerts and sporting events through campus student governments.[32]

Strengths and Limitations

Published data on noise exposure, hearing symptoms, attitude toward noise, and use of hearing protection among college students are limited. Hence, this study on a large sampling population of college students contributes to the existing body of literature on hearing health among this segment of the young population. This study may provide a greater understanding of the college students’ noise exposures, particularly in North Carolina, compared to other college students and other groups of young adults. The results of this study can serve as a baseline for more in-depth and large-scale studies aimed at further investigating the noise exposures and related hearing effects among college students in other universities and states. The findings of this study may be used to develop specific hearing conservation programs tailored to college students and other young adults, and interventions and policies related to noise exposure reduction to prevent or reduce their risk to NIHL and other hearing symptoms.

Some of the main study limitations include self-reporting, recall bias, and selection bias. The information collected from the college students regarding their hearing symptoms was self-reported and was not verified by clinical records or audiometric tests due to the anonymity of the survey. Recall bias may have affected the results on some noise exposures and hearing protection use that were associated with noisy activities that were rarely performed. Participants who had hearing symptoms might have also been more likely recall their prior rare noise exposures than those who had not, which may have possibly exaggerated the association between hearing symptoms and noise exposure. Additionally, college student participants in this study represent a single university in the US. The results may not represent other universities with different student demographics and youth cultures. Another limitation of the study is the length of the survey. Although including 44 items in the survey may have resulted in a large amount data, there may also be a possibility of participants providing more random responses to questions toward the end of the survey. Lastly, some factors that may contribute to hearing symptoms, such as exposure to ototoxins due to drug abuse,[49] were not addressed in the survey.

Our findings suggest that college students have significant noise exposures and that improving their knowledge and attitudes through education on hearing health may result in better hearing protection behaviors. Such findings are of great concern because excessive noise exposures early in life that may result in slight hearing loss can develop into severe hearing loss in late adulthood. To reduce this risk among the young population, educational initiatives and awareness campaigns on hearing conservation must be carefully developed to better inform college students on how to protect their hearing from excessive noise and to encourage them in a better manner to take such precautions to prevent NIHL. A significant amount of education to encourage hearing protective behavior must involve various stakeholders including the college students, parents, health service providers, schools, and universities/colleges. The integration of a hearing health and conservation topic into a required health course as part of the college curriculum, the promotion of hearing conservation by university and college student health services and student organizations, and the implementation of university policies to reduce noise exposures on campus may provide valuable avenues in disseminating the information on noise exposure and hearing conservation among college students.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Karen Vail-Smith of the ECU Department of Health Education and Promotion for her assistance in the administration of the survey.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adolescent and School Health: Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Last accessed on 2014 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/noise/index.htm .

- 2.Martin WH, Sobel J, Griest SE, Howarth L, Shi Y. Noise induced hearing loss in children: Preventing the silent epidemic. J Otol. 2006;1:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward WD, Royster JD, Royster LH. Auditory and nonauditory effects of noise. In: Berger EH, Royster LH, Royster JD, Driscoll DP, Layne M, editors. The Noise Manual. 5th ed. Fairfax, VA: American Industrial Hygiene Association Press; 2000. pp. 123–47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung JH, Des Roches CM, Meunier JE, Eavey RD. Evaluation of noise-induced hearing loss in young people using a web-based survey technique. Pediatrics. 2005;115:861–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PA, Davis A, Ferguson M, Lutman ME. The prevalence and type of social noise exposure in young adults in England. Noise Health. 2000;2:41–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West PD, Evans EF. Early detection of hearing damage in young listeners resulting from exposure to amplified music. Br J Audiol. 1990;24:89–103. doi: 10.3109/03005369009077849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer-Bisch C. Epidemiological evaluation of hearing damage related to strongly amplified music (personal cassette players, discotheques, rock concerts)--high-definition audiometric survey on 1364 subjects. Audiology. 1996;35:121–42. doi: 10.3109/00206099609071936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Opperman DA, Reifman W, Schlauch R, Levine S. Incidence of spontaneous hearing threshold shifts during modern concert performances. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:667–73. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadhra S, Jackson CA, Ryder T, Brown MJ. Noise exposure and hearing loss among student employees working in university entertainment venues. Ann Occup Hyg. 2002;46:455–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serra MR, Biassoni EC, Richter U, Minoldo G, Franco G, Abraham S, et al. Recreational noise exposure and its effects on the hearing of adolescents. Part I: An interdisciplinary long-term study. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:65–73. doi: 10.1080/14992020400030010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beach EF, Gilliver M, Williams W. A snapshot of young adults’ noise exposure reveals evidence of “binge listening”. Appl Acoust. 2014;77:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niskar AS, Kieszak SM, Holmes AE, Esteban E, Rubin C, Brody DJ. Estimated prevalence of noise-induced hearing threshold shifts among children 6 to 9 years of age: The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994, United States. Pediatrics. 2001;108:40–3. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morioka I, Luo WZ, Miyashita K, Takeda S, Wang YX, Li SC. Hearing impairment among young Chinese in a rural area. Public Health. 1996;110:293–7. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(96)80092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Klein BE, Klein R, Tweed TS. Association of leisure-time noise exposure and hearing loss. Audiology. 2001;40:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen-Widen SE, Erlandsson SI. Self-reported tinnitus and noise sensitivity among adolescents in Sweden. Noise Health. 2004;7:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogoch II, House RA, Kudla I. Perceptions about hearing protection and noise-induced hearing loss of attendees of rock concerts. Can J Public Health. 2005;96:69–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03404022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosanowski F, Eysholdt U, Hoppe U. Influence of leisure-time noise on outer hair cell activity in medical students. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006;80:25–31. doi: 10.1007/s00420-006-0090-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zocoli AM, Morata TC, Marques JM, Corteletti LJ. Brazilian young adults and noise: Attitudes, habits, and audiological characteristics. Int J Audiol. 2009;48:692–9. doi: 10.1080/14992020902971331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degeest S, Corthals P, Vinck B, Keppler H. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus after leisure noise exposure in young adults. Noise Health. 2014;16:26–33. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.127850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong M, Yang C, Lai H, Wang J. Impulse noise exposure in early adulthood accelerates age-related hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:1351–4. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2622-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lees RE, Roberts JH, Wald Z. Noise induced hearing loss and leisure activities of young people: A pilot study. Can J Public Health. 1985;76:171–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erlandsson SI, Hallberg LR. Prediction of quality of life in patients with tinnitus. Br J Audiol. 2000;34:11–20. doi: 10.3109/03005364000000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widen SE, Holmes AE, Erlandsson SI. Reported hearing protection use in young adults from Sweden and the USA: Effects of attitude and gender. Int J Audiol. 2006;45:273–80. doi: 10.1080/14992020500485676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson O, Andrew B, Walker D, Morgan S, Aldren A. British university students’ attitudes towards noise-induced hearing loss caused by nightclub attendance. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128:29–34. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113003241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes AE, Widén SE, Erlandsson S, Carver CL, White LL. Perceived hearing status and attitudes toward noise in young adults. Am J Audiol. 2007;16:S182–9. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2007/022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widen SE, Holmes AE, Johnson T, Bohlin M, Erlandsson SI. Hearing, use of hearing protection, and attitudes towards noise among young American adults. Int J Audiol. 2009;48:537–45. doi: 10.1080/14992020902894541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chesky K, Pair M, Lanford S, Yoshimura E. Attitudes of college music students towards noise in youth culture. Noise Health. 2009;11:49–53. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.45312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crandell C, Mills TL, Gauthier R. Knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes about hearing loss and hearing protection among racial/ethnically diverse young adults. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:176–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rawool VW, Colligon-Wayne LA. Auditory lifestyles and beliefs related to hearing loss among college students in the USA. Noise Health. 2008;10:1–10. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.39002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erlandsson SI, Olsen SE. Hearing symptom description (HSD) In: Olsen SE, editor. Psychological Aspects of Adolescents’ Perceptions and Habits in Noisy Environments. Licentiate Dissertation. Sweden: Department of Psychology, Göteborg University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erlandsson SI, Olsen SE. Adolescent habits and use of hearing protection (AHH) In: Olsen SE, editor. Psychological Aspects of Adolescents’ Perceptions and Habits in Noisy Environments. Licentiate Dissertation. Sweden: Department of Psychology, Göteborg University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lass NJ, Woodford CM, Everly-Myers DS. A survey of college students’ knowledge and awareness of hearing, hearing loss, and hearing health. NSSLHA J. 1990;17:90–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bain-Selbo E. Game day and God: Football, faith and politics in the American South. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press; 2009. p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engard DJ, Sandfort DR, Gotshall RW, Brazile WJ. Noise exposure, characterization, and comparison of three football stadiums. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2010;7:616–21. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2010.510107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rawool VW. Hearing conservation in educational settings. In: Rawool VW, editor. Hearing Conservation: Occupational, Recreational, Educational, and Home Settings. New York: Thieme; 2012. p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melville, NY: Newsday; 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Oct 26]. Associated Press. Kansas City Chiefs break Seattle Seahawks’ Guinness Noise Record. Available from: http://www.newsday.com/sports/football/kansas-city-chiefs-break-seattleseahawks-guinness-noise-record-1.9440535 . [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodgetts WE, Liu R. Can hockey playoffs harm your hearing? CMAJ. 2006;175:1541–2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cranston CJ, Brazile WJ, Sandfort DR, Gotshall RW. Occupational and recreational noise exposure from indoor arena hockey games. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2013;10:11–6. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2012.736341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.England B, Larsen JB. Noise levels among spectators at an intercollegiate sporting event. Am J Audiol. 2014;23:71–8. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2013/12-0071). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:356–86. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azjen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Betz CL. The dangers of rock concerts. J Pediatr Nurs. 2000;15:341–2. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2000.20782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer R. Can Minneapolis make Earplugs Cool? Minneapolis, MN: City Pages; 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Oct 26]. Available from: http://blogs.citypages.com/gimmenoise/2014/06/can_minneapolis_make_earplugs_cool.php . [Google Scholar]

- 44.Folmer RL, Griest SE, Martin WH. Hearing conservation education programs for children: A review. J Sch Health. 2002;72:51–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H, Huang M, Wei J. Elementary school children's knowledge and intended behavior towards hearing conservation. Noise Health. 2008;10:105–9. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.44349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lukes E, Johnson M. Hearing conservation: An industry-school partnership. J Sch Nurs. 1999;15:22–5. doi: 10.1177/105984059901500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2001. [Last accessed on 2014 Oct 26]. GenerationRx.com. How young people use the Internet for health information. Available from: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2001/11/3202-genrx-report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; [Last accessed on 2014 Oct 26]. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). WISE EARS!®. Available from: http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/wise/Pages/Default.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rawool V, Dluhy C. Auditory sensitivity in opiate addicts with and without a history of noise exposure. Noise Health. 2011;13:356–63. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.85508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]