Abstract

Recent findings show the importance of acceptance in the treatment of chronic tinnitus. So far, very limited research investigating the different levels of tinnitus acceptance has been conducted. The aim of this study was to investigate the quality of life (QoL) and psychological distress in patients with chronic tinnitus who reported different levels of tinnitus acceptance. The sample consisted of outpatients taking part in a tinnitus coping group (n = 97). Correlations between tinnitus acceptance, psychological distress, and QoL were calculated. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to calculate a cutoff score for the German “Tinnitus Acceptance Questionnaire” (CTAQ-G) and to evaluate the screening abilities of the CTAQ-G. Independent sample t-tests were conducted to compare QoL and psychological distress in patients with low tinnitus acceptance and high tinnitus acceptance. A cutoff point for CTAQ-G of 62.5 was defined, differentiating between patients with “low-to-mild tinnitus acceptance” and “moderate-to-high tinnitus acceptance.” Patients with higher levels of tinnitus acceptance reported a significantly higher QoL and lower psychological distress. Tinnitus acceptance plays an important role for patients with chronic tinnitus. Increased levels of acceptance are related to better QoL and less psychological distress.

Keywords: Acceptance, psychological distress, quality of life (QoL), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, tinnitus

Introduction

Tinnitus is defined as a subjective acoustic perception in the absence of any external source.[1] Epidemiological studies reported a prevalence of 10-16% for chronic tinnitus in the adult population; the prevalence of tinnitus increases with age.[2] While the majority of the population is unaffected by tinnitus, 0.5-3% of the adult population develop severe distress and experience impairment in everyday life, sleep, mood, concentration, and daily work.[3,4] Moreover, distressing tinnitus is often associated with psychological problems such as anxiety and depressive symptoms.[2,5] In accordance with the current state of art in psychological tinnitus research,[6,7,8] in this study tinnitus is defined as chronic if persistent for 6 months or longer.[3]

Since only a small proportion of patients with tinnitus are impaired by the symptom, it is useful in a clinical setting to assess the need for treatment by differentiating between patients with “low level tinnitus distress” and “high level tinnitus distress.”[9] Tinnitus distress is considered to be of low level if the patient experiences mild-to-moderate tinnitus distress or only feels impaired in specific situations such as quietness, stress, or physical tension. High level tinnitus distress describes a state in which patients report high or very high distress due to tinnitus, significant impairment in different areas of life, different secondary symptoms in mood (e.g., depression), and cognitive impairment (e.g., reduced power of concentration).[9,10]

The subjectively experienced distress due to tinnitus cannot be sufficiently explained by psychoacoustic parameters such as tinnitus loudness.[11] Due to this, psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, or catastrophizing have been assumed to be adjuvant to explain tinnitus distress.[9,12,13,14] The process by which episodic tinnitus becomes chronic and the severity of chronic tinnitus are strongly influenced by tinnitus-related cognitions and coping strategies.[12,15] Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown as an effective treatment to reduce annoyance and distress associated with tinnitus.[16,17] CBT aims to decrease tinnitus distress by means of applied relaxation and change attention bias, negative thoughts, and beliefs in relation to tinnitus by the means of distraction techniques, imagery, and cognitive restructuring.[8] Nevertheless, there is room for improvement, as a substantial number of patients continue to experience significant residual tinnitus distress after treatment[16] that underscores the importance of new developments within established CBT interventions.[8,18] Considering the heterogeneity among individuals with tinnitus (e.g., in terms of age, degree of hearing loss, and comorbid symptoms), it seems unlikely for one treatment to be beneficial for all participants with tinnitus.[8,19] Therefore, in the recent development of CBT for chronic tinnitus,[6,7,8,18] acceptance-based approaches such as the “Acquired centralized tinnitus” (ACT)[20] and elements of the “Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy”[21] have been integrated.

The word “acceptance” stems from the Latin word “accipere” that means “admit, let in, hear, learn.” Psychological acceptance is described as a mindful and nonevaluative approach to internal experiences such as emotions, physical sensations, or thoughts.[20] Acceptance has been further described as the openness to experience thoughts and emotions as they are while refraining from attempting to directly and actively change these situations, feelings, and thoughts.[22] Patients who find their tinnitus unacceptable are more likely to try to avoid or reduce the experience of tinnitus.[8] In accordance with the theory of experiential avoidance,[20] attempts to avoid or reduce the experience could intensify and increase the very sensation one is trying to control or avoid, creating a vicious circle of more avoidance and increased tinnitus distress. Therefore, patients might achieve better adjustment if the tinnitus was approached rather than avoided. Giving up trying to control or avoid the tinnitus can enable more flexible ways of responding to the tinnitus that can ultimately lead to the opportunity of leading a satisfying life despite having tinnitus.[8] Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for the treatment of chronic tinnitus includes psychoeducation regarding tinnitus; the evaluation of the patients’ current coping strategies in relation to tinnitus and the examination of costs and benefits of these coping strategies; changing tinnitus-related behavioral patterns; exercises to approach the tinnitus sound and related reactions in a nonjudgemental way; and working with values and life goals.[6] It has been critically discussed about whether acceptance-based therapy approaches are a “new wave” in CBT or if acceptance strategies are just another tool in the arsenal of a cognitive-behavioral therapist.[23] Acceptance can be considered as one of the key features of psychotherapeutic treatment for tinnitus.[13,18]

In order to evaluate the efficacy of acceptance-orientated treatment in changing levels of acceptance, it is necessary to have specific and sufficiently validated instruments to measure change in acceptance. In the treatment of chronic pain, acceptance oriented instruments such as the “Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire” (CPAQ)[24] have already been developed and validated. Due to the similarities often described between pain and tinnitus,[19,25] CPAQ has been adapted for tinnitus in English[26] as well as German.[27] The German version of this adaptation — The “Chronic Tinnitus Acceptance Questionnaire” (CTAQ-G) was recently validated in a clinical sample. A good internal consistency (CTAQ-G α = 0.874) was reported and factor analysis revealed a two-factor solution. The convergent validity was assessed with the total score of the German Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ) and showed clear negative correlations between tinnitus distress and acceptance of chronic tinnitus.[28]

Methods

Sample

The sample (n = 97) consisted of outpatients taking part in a tinnitus coping group at the Tinnitus Clinic of the Department of Medical Psychology (Medical University of Innbruck, Tyrol, Austria). The tinnitus coping group was offered a standard clinical treatment for patients with chronic tinnitus for over a decade. Patients were referred to the Tinnitus Clinic by ear-nose-throat (ENT) specialists. The research was a retrospective analysis of the data collected in routine clinical care. Initially n = 102 participants with chronic tinnitus were included in the study. Five participants were excluded as their questionnaires were incomplete. The patients filled out the questionnaires at the beginning of the group therapy.

Procedure

Patients who referred to the tinnitus clinic took part in a clinical interview, conducted by an experienced clinical psychologist, that assessed tinnitus distress and psychiatric comorbidities as well as their ability to take part in the group therapy. Furthermore, tinnitus distress was assessed with the TQ.[29] At the start of the tinnitus coping group, the participants were asked to take psychological tests as part of the routine clinical practice including the TQ, Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF-36), and CTAQ-G. The participants were given a consent form and were informed about the study and standards of anonymization.

Patients were included in the group therapy if they reported chronic tinnitus (>6 months), showed a score of >30 on the TQ, were at least 18 years of age, had been examined by an ENT specialist, spoke enough German to fully understand the tests, and had no severe psychiatric disorder diagnosed in the clinical psychological interview. To obtain a patient sample close to clinical reality, the same inclusion criteria was used for the present study. Tinnitus frequency, tinnitus intensity, hearing impairment, and hyperacusis were assessed by a speech and language therapist at the Department for Hearing, Speech, and Voice Disorders before the beginning of the psychological treatment.

The research took place within the clinical procedure and was part of an overall research project on tinnitus acceptance in patients with chronic tinnitus. The aims of this project were to assess how to quantify acceptance in patients with chronic tinnitus and to find out about what kind of a relationship exists between acceptance and factors such as depression, anxiety, and interpersonal aspects. Furthermore, the relationship between medical data, such as hearing impairment and tinnitus-specific characteristics, were assessed.

Measures

Acceptance in chronic tinnitus

The acceptance of chronic tinnitus was measured by CTAQ-G [German translation: “Akzeptanzfragebogen bei Chronischem Tinnitus” (AFCT)] that is an adaption of the German version of the “Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (CPAQ)”[24] for tinnitus, replacing the word “pain” with “tinnitus.” The CTAQ-G consists of 20 items assigned to two subscales, “activity engagement” and “tinnitus willingness” as well as a total score. Activity engagement measures the extent of participation in the usual daily activities regardless of acknowledged tinnitus and tinnitus willingness measures the willingness of the patient to have tinnitus present without trying to avoid or reduce it.[24,28] A validation of the CTAQ-G showed an internal consistency of α = 0.874 for the total score, α = 0.831 for the subscale activity engagement, and α = 0.817 for the subscale tinnitus willingness. Acceptance was highly correlated with less tinnitus distress.[28]

Tinnitus distress

The tinnitus distress was measured with the German “Tinnitus Questionnaire” (TQ),[29] an instrument to assess the general level of tinnitus-related psychological and psychosomatic distress. The TQ is the German adaption of the TQ.[30] The TQ consists of 52 items and six subscales (emotional and cognitive distress, intrusiveness, auditory perceptual difficulties, sleep disturbance, and somatic complaints) that can be interpreted individually as well as a total score (0-84). According to its total score, the TQ is divided in four distress levels: Mild (0-30), moderate (31-46), severe (47-59), and very severe (60-84). The last two levels (severe and very severe) are described as “decompensated tinnitus” (high-level tinnitus distress) and the first two levels (mild and moderate) are described as “compensated tinnitus” (low-level tinnitus distress). A retest reliability of .94 and good validity has been reported.[29]

Global psychological distress

The global psychological and psychosomatic distress was assessed with the German version of the “Brief Symptom Inventory.”[31] The BSI consists of 53 items that can be divided into nine subscales (somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism) and three scales to capture global psychological distress. Retest reliability between .73 and .93 and good validity for the subscales were reported.[31,32]

Quality of life (QoL)

The health status was measured with the German version of the SF-36.[33] The SF-36 is a broadly used, well-established instrument to assess QOL. The SF-36 consists of 36 items that can be divided into eight subscales (vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social role functioning, and mental health) and a physical and psychological total score. The subscale's internal consistencies were tested in nine samples, showing a Cronbach's alpha between .74 and .94. Good validity has been reported in several studies.[33]

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis IBM SPSS Statistics (version 20) was used. Two-sided product-moment Spearmen correlations were calculated to investigate the relationship between tinnitus acceptance, psychological distress, and QoL in the present sample. A value of P < 0.05 was defined as significant.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve[34] was used to determine the sensitivity and specificity of CTAQ-G. Cutoff values that best distinguish between patients with low level and high level tinnitus distress were defined. A ROC plot was produced by plotting the true positive rate (sensitivity) versus the false positive rate (1-specificity). Sensitivity was defined as the number of patients who were correctly identified by the CTAQ-G to experience high-level tinnitus distress, divided by the number of all patients who were identified as experiencing high level tinnitus distress by the TQ. Specificity was defined as the number of patients who were correctly identified by CTAQ-G to show a low-level tinnitus distress, divided by the number of patients who were identified as showing low level tinnitus distress by the TQ. If the “cost” of a false negative result was the same as that of a false positive result, the best cutoff was that which maximized the sum of the sensitivity and specificity.

Positive predictive value (PPV) was defined as the number of patients who were correctly identified by the CTAQ-G as experiencing high-level tinnitus, distress divided by the number of all patients who were identified as experiencing high-level tinnitus distress by the CTAQ-G. Negative predictive value (NPV) was defined as the number of patients who were correctly identified by the CTAQ-G to show low-level tinnitus distress divided by the number of all the patients who were identified showing low level tinnitus distress by the CTAQ-G.

Accuracy was defined as the number of patients who were classified correctly divided through the number of all patients in the sample. The overall misclassification rate (OMR) was defined as the patients who were identified falsely as positive or negative by the CTAQ-G, divided by all the patients.

The prevalence of the disease strongly influences the predictive value of a test.[35] Therefore, it is important to take the incidence of the symptoms into account when calculating the predictive values. In this study, the calculation was based on the incidence within the sample, measured by the quantity of patients with high-level tinnitus distress.

Finally, independent sample t-tests were used to assess whether patients with “low-to-mild tinnitus acceptance” reported significantly different psychological distress and QoL than patients with “moderate-to-high tinnitus acceptance.”

Results

Sample

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Of the participants, 45.4% were females and 54.6% were males. The age of the participants ranged from 20 years to 75 years (mean 52 years) and 67% were married. Also, 44.3% were working fulltime or part-time and 38.5% were either retired or in the process of retiring.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic data

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD*) | 51.9 (11.0) |

| Minimum-maximum | 20.0-75.0 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 53 (54.6) |

| Female | 44 (45.4) |

| Missing data | 0 (0.0) |

| Working Situation | |

| Not working | 13 (14.3) |

| Part time job | 8 (8.2) |

| Fulltime job | 35 (36.1) |

| Retirement (or recently applied for retirement) | 35 (38.5) |

| Missing data | 6 (6.2) |

| Living situation | |

| Living alone | 12 (12.4) |

| Living with partner/family/children/flat share | 65 (67.0) |

| Living in an institution | 2 (2.1) |

| Missing data | 18 (18.6) |

| Relationship status | |

| Married/domestic partnership/partnership (>1 year) | 66 (68.0) |

| Widower | 3 (3.1) |

| Unmarried | 16 (16.5) |

| Divorced/Broken up | 11 (11.3) |

| Missing data | 1 (1.0) |

| Sick leave | |

| Currently on sick leave (>3 months) | 12 (12.4) |

| Currently not on sick leave (>3 months) | 85 (87.6) |

*SD = Standard deviation

Table 2 shows the medical characteristics of the sample. Tinnitus intensity was measured in decibel normal hearing level (dB nHL) at the pitch matched frequency. Tinnitus frequency was obtained by the patient's pitch matching with pure tones and sounds with different frequencies. Hearing impairment was defined as the hearing thresholds outside the normal hearing range of 0-20dB nHL; hyperacusis was defined as the uncomfortable level (UCL) with pure tones less than 80dB nHL. UCL testing was conducted by the presentation of seven different pure tones with increasing loudness. The mean tinnitus duration was 5.5 years; 71% had a diagnosed hearing impairment and 52% a diagnosis of hyperacusis. Independent samples t-test including the Levene's test for equality of variances showed that patients with hearing impairment and without hearing impairment did not significantly differ in acceptance (t = 1.46, P = .15), tinnitus distress (t = .31, P = .75), global psychological distress (t = .09, P = .92), or well-being (t = .34, P = .74).

Table 2.

Medical data

| Characteristics of the tinnitus | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean tinnitus duration in years (SD*) | 5.5 (6.8) |

| Mean tinnitus frequency (SD) | |

| <1 KHz | 7 (7.2) |

| 1-3 KHz | 17 (17.5) |

| >3 KHz | 38 (39.2) |

| Missing data | 35 (36.1) |

| Tinnitus intensity | |

| <15 dB HL** | 40 (41.2) |

| >15 dB HL | 22 (22.7) |

| Missing data | 35 (36.1) |

| Hearing impairment | |

| Yes | 69 (71.1) |

| Yes: One side | 10 (10.3) |

| Yes: Both sides | 59 (60.8) |

| No | 23 (23.7) |

| Missing data | 5 (5.2) |

| Hyperacusis | 51 (52.6) |

| Missing data | 17 (17.5) |

| Localization of tinnitus | |

| One side | 28 (28.9) |

| Both sides | 48 (49.5) |

| In the head | 10 (10.3) |

| Missing data | 11 (11.3) |

*SD = Standard deviation, **dB HL = Decibel hearing level, Mean tinnitus frequency and mean tinnitus intensity across subjects, pitch matching was conducted using band noise or pure tones

Clinical findings

In this sample, highly significant (P < 0.01) negative correlations between acceptance and all TQ subscales (except auditory perceptual difficulties) as well as the TQ total score were found. Comparing the QoL to acceptance, highly significant positive correlations were found between acceptance and social functioning (r = .55, P < 0.01) as well as mental health (r = .49, P < 0.01). Compared to general psychological distress, significantly low-to-moderate (P < 0.05) negative correlations were found between tinnitus acceptance and all the BSI subscales and the Global Severity Index (GSI). The strongest correlations were found between tinnitus acceptance and depression (CTAQ-G: r = –.48; P < 0.01), tinnitus acceptance and anxiety (CTAQ-G: r = –.48; P < 0.01) as well as between tinnitus acceptance and global psychological distress (CTAQ-G: r = –.43; P < 0.01). For details, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation CTAQ-G, TQ, SF-36, and BSI

| TQ, SF-36, BSI | CTAQ-G |

|---|---|

| TQ - Emotional distress | −.594** |

| TQ - Cognitive distress | −.484** |

| TQ - Intrusiveness | −.368** |

| TQ - Auditory perceptual difficulties | −.191 |

| TQ - Sleep disturbance | −.240* |

| TQ - Somatic complaints | −.286** |

| TQ - Total score | −.557** |

| SF-36 physical functioning | .115 |

| SF-36 role - physical | .258* |

| SF-36 bodily pain | .255* |

| SF-36 general health | .331** |

| SF-36 vitality | .396** |

| SF-36 social functioning | .545** |

| SF-36 role - emotional | .346** |

| SF-36 mental health | .498** |

| SF-36 physical health summary | .116 |

| SF-36 mental health summary | .501** |

| BSI somatization | −.238* |

| BSI obsessive-compulsive | −.343** |

| BSI interpersonal sensitivity | −.362** |

| BSI depression | −.479** |

| BSI anxiety | −.482** |

| BSI hostility | −.373** |

| BSI phobic anxiety | −.334** |

| BSI paranoid ideation | −.285** |

| BSI psychoticism | −.356** |

| BSI Global Severity Index (GSI) | −.428** |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

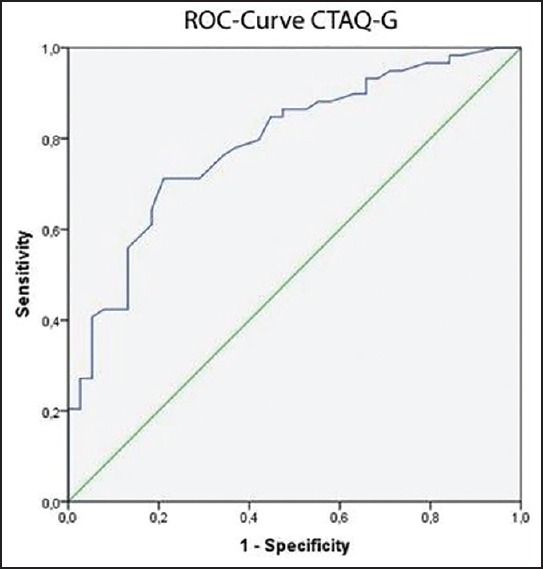

A ROC-analysis was performed to determine a cutoff score to discriminate between “low-to-mild tinnitus acceptance” and “moderate-to-high tinnitus acceptance.” Negative cases included patients with a TQ score of 46 or lower, defined as “low-level tinnitus distress” (n = 38; 39.2%). Positive cases included patients with a TQ score of 47 or higher, defined as “high level tinnitus distress” (n = 59; 60.8%). The ROC-analysis has shown an “area under curve” (AUC) of .79 [confidence interval (CI) 95% 0.69 -0.88; P < 0.01; Figure 1] for the CTAQ-G.

Figure 1.

ROC curve CTAQ-G

The CTAQ-G is an instrument to determine whether a patient with tinnitus shows high or low rates of tinnitus acceptance. Patients testing lower than the defined cutoff show a lower rate of acceptance. Acceptance is a well-known mediator for tinnitus distress;[6,13] therefore, the cutoff was chosen such that it increased the PPV to an arguable maximum.

The optimal cutoff point for the CTAQ-G considering the lowest false-negative ratio has shown to be CTAQ-G = 62.5. At this score the scale's sensitivity was .71, specificity .79, OMR .26, and the accuracy .74. The CTAQ-G's PPV in our sample was.84 that means that the likelihood of a low value on the CTAQ-G reflecting high level tinnitus distress was at 84%. The NPV in our sample was 0.64 that means that the likelihood of a high value on the CTAQ-G reflecting low level tinnitus distress was at 64%. Patients with a score <62.5 were defined to show “low-to-mild tinnitus acceptance” and patients with a score >62.5 to show “moderate-to-high tinnitus acceptance.”

Finally, these two groups were compared in terms of their global psychological distress and their QoL through the independent samples t-test and the Levene's test for homogeneity of variance. The t-test [Table 4] showed highly significant differences between patients with “low-to-mild tinnitus acceptance” and patients with “moderate-to-high tinnitus acceptance” regarding their psychological QoL (t = 4.48, P < 0.001) and their psychological distress (t = 4.15, P < 0.001). No significant difference was found between the two groups regarding the physical aspect of their QoL (t = .61, P = .26).

Table 4.

Low-to-mild tinnitus acceptance (low acceptance) versus moderate-to-high tinnitus acceptance (high acceptance)

| TQ, SF-36, BSI | CTAQ-G | N | MA | SD | Mean standard error | Sign. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 physical functioning | Low acceptance | 50 | 73.00 | 25.29 | 3.57 | 0.34 |

| High acceptance | 46 | 77.80 | 23.94 | 3.53 | ||

| SF-36 role-physical | Low acceptance | 49 | 45.91 | 45.74 | 6.53 | 0.81 |

| High acceptance | 46 | 61.95 | 42.73 | 6.30 | ||

| SF-36 bodily pain | Low acceptance | 49 | 54.75 | 30.92 | 4.41 | 0.15 |

| High acceptance | 46 | 63.32 | 27.10 | 3.99 | ||

| SF-36 general health | Low acceptance | 50 | 51.14 | 16.10 | 2.27 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 45 | 61.84 | 17.66 | 2.63 | ||

| SF-36 vitality | Low acceptance | 50 | 37.70 | 18.75 | 2.65 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 45 | 49.55 | 17.80 | 2.65 | ||

| SF-36 social functioning | Low acceptance | 50 | 49,75 | 24.93 | 3.52 | <0.001 |

| High acceptance | 46 | 76.90 | 26.34 | 3.88 | ||

| SF-36 role-emotional | Low acceptance | 49 | 39.45 | 48.43 | 6.91 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 46 | 68.11 | 43.86 | 6.46 | ||

| SF-36 mental health | Low acceptance | 50 | 46.32 | 18.97 | 2.68 | <0.001 |

| High acceptance | 45 | 62.20 | 18.66 | 2.78 | ||

| SF-36 physical health summary | Low acceptance | 49 | 44.55 | 11.49 | 1.64 | 0.54 |

| High acceptance | 45 | 45.94 | 10.45 | 1.55 | ||

| SF-36 mental health summary | Low acceptance | 49 | 33.38 | 12.18 | 1.74 | <0.001 |

| High acceptance | 45 | 44.62 | 12.08 | 1.80 | ||

| BSI somatization | Low acceptance | 50 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 0.11 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.07 | ||

| BSI obsessive-compulsive | Low acceptance | 50 | 1.29 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.09 | ||

| BSI interpersonal sensitivity | Low acceptance | 50 | 1.14 | 1.00 | 0.14 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.08 | ||

| BSI depression | Low acceptance | 50 | 1.16 | 1.02 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.07 | ||

| BSI anxiety | Low acceptance | 50 | 1.24 | 0.87 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.06 | ||

| BSI hostility | Low acceptance | 50 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 0.10 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.06 | ||

| BSI phobic anxiety | Low acceptance | 49 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.12 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.08 | ||

| BSI paranoid ideation | Low acceptance | 50 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.13 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.08 | ||

| BSI psychoticism | Low acceptance | 50 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.11 | <0.01 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.07 | ||

| BSI Global Severity Index (GSI) | Low acceptance | 50 | 1.05 | 0.73 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| High acceptance | 47 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.05 |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of tinnitus acceptance on QoL and psychological distress in a sample of patients with chronic tinnitus. In accordance with recent research,[6,8,18] increased tinnitus acceptance was significantly correlated with lower tinnitus distress and lower psychological distress. Patients with higher acceptance described their tinnitus as less intrusive while fewer sleep disturbances and somatic complaints were reported.

Although several studies have investigated the influence of tinnitus on a patient's QoL, only a few studies have considered the correlation between acceptance and QoL.[8,36] In the present study, significant correlations between acceptance of the tinnitus and aspects of QoL were found. The patients who accepted their tinnitus better also reported higher vitality, better mental health, and less influence of physical and emotional problems on normal social activities and daily activities. It would be advisable to further investigate the relationship between patients’ acceptance of their tinnitus and their QoL.

Tinnitus acceptance was measured with the CTAQ-G. A cutoff value of CTAQ-G = 62.5 was calculated to best differentiate patients with “low-to-mild tinnitus acceptance” from patients with “moderate-to-high tinnitus acceptance.” The sensitivity and specificity for the CTAQ-G were calculated based partially on the epidemiological base of the sample. In this sample, 60.8% of the patients were experiencing high-level tinnitus distress. Due to the area under the curve of AUC = 0.79 for CTAQ-G, it can be considered a fairly reliable test to determine the acceptance of tinnitus.

The differences between patients with lower and higher acceptance regarding their psychological distress and QoL were as expected. Patients with higher tinnitus acceptance reported decreased symptoms of the following: Somatization, obsessive-compulsive behavior, interpersonal sensitivity, depression and anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, and global psychological distress. Furthermore, patients with higher tinnitus acceptance reported better general health, more vitality, less interference with normal social activities due to physical and emotional problems, and better mental health. Therefore, our findings clearly underscore the importance of acceptance-oriented elements in the treatment of tinnitus distress.

Recent studies show that acceptance plays an important role in the reduction of tinnitus distress[8,18] and that the process of acceptance is also influenced in treatments that do not include specific acceptance oriented methods.[36,37] Most forms of psychological interventions for tinnitus (e.g., CBT, ACT) feature psychoeducation that is also an element in counseling by ENT specialists and audiologists and in the tinnitus retraining therapy.[38] Psychoeducation includes information on the nature and characteristics of tinnitus, its epidemiology and etiology, and various adaptive and ineffective coping strategies.[7] Several authors[7] report a clear positive effect of psychoeducation on negative affectivity, rumination, and difficulties due to tinnitus. We hypothesize that in tinnitus counseling and tinnitus retraining therapy, acceptance might be influenced by psychoeducation and other treatment elements. It, therefore, seems worthwhile to investigate these treatment processes with an adequate instrument measuring tinnitus acceptance in order to improve the understanding of helpful processes in tinnitus treatment.

Some limitations of this study have to be considered. First and most importantly, the sample consisted of patients actively seeking psychological help because of tinnitus distress that caused a higher prevalence of tinnitus distress in the group than in the general population. In our study 60.8% of the patients were suffering strongly from tinnitus distress, whereas the prevalence of high-level tinnitus distress in the adult population is between 0.5% and 3%.[3,4] Since CTAQ-G is designed to investigate tinnitus acceptance in a clinical population, we consider our sample to be representative of tinnitus outpatients.

The differentiation between lower tinnitus acceptance and higher tinnitus acceptance is based partially on the total score of the TQ used at the time. This raised an issue since an instrument measuring tinnitus distress does not employ the same construct as an instrument measuring the acceptance of tinnitus. Therefore, the best choice would be to use an already validated test as a state variable in the ROC analysis. Unfortunately, currently there is no German instrument measuring tinnitus acceptance that has been validated adequately enough to serve as a state variable. We, therefore, chose an instrument that was as closely related to the construct of acceptance as possible. Since there is strong evidence of a relationship between tinnitus acceptance and tinnitus distress,[6,8,18] we chose the total score of the TQ that is a well-established and broadly used instrument in the assessment of tinnitus distress as state variable.

Conclusion

Higher tinnitus acceptance was strongly correlated with lower tinnitus distress and general psychological distress, and with higher QoL. Instruments measuring tinnitus acceptance, such as the CTAQ-G, are recommended for use in clinical practice and for the evaluation of acceptance-based therapies (e.g., ACT). Further research should focus on the understanding of acceptance-building factors in psychological treatment as well as in audiological and medical treatments.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by a PhD Research Grant of the Vice-Rectorate for Research, Leopold-Franzens-University Innsbruck, Austria.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hallam RS, Rachman S, Hinchcliffe R. Psychological aspects of tinnitus. In: Rachman S, editor. Contributions to Medical Psychology. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1980. pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med. 2010;123:711–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis A, El Refaie A. Epidemiology of tinnitus. In: Tyler RS, editor. Tinnitus Handbook. San Diego: Singular; 2000. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Rochtchina E, Krapa MJ, Mitchell P. Incidence, persistence, and progression of tinnitus symptoms in older adults: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear Hear. 2010;31:407–12. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181cdb2a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milerová J, Anders M, Dvořák T, Sand PG, Königer S, Langguth B. The influence of psychological factors on tinnitus severity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westin V, Schulin M, Hesser H, Karlsson M, Noe R, Olofsson U, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy versus tinnitus retraining therapy in the treatment of tinnitus: A randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:737–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philippot P, Nef F, Clauw L, de Romrée M, Segal Z. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for treating tinnitus. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;19:411–9. doi: 10.1002/cpp.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hesser H, Gustafsson T, Lundén C, Henrikson O, Fattahi K, Johnsson E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of tinnitus. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:649–61. doi: 10.1037/a0027021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stobik C, Weber RK, Münte TF, Walter M, Frommer J. Evidence of psychosomatic influences in compensated and decompensated tinnitus. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:370–8. doi: 10.1080/14992020500147557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weise C. Tinnitus. Psychotherapeut. 2011;56:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry JA, Meikle MB. Psychoacoustic measures of tinnitus. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000;11:138–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budd RJ, Pugh R. The relationship between coping style, tinnitus severity and emotional distress in a group of tinnitus sufferers. Br J Health Psychol. 1996;1:219–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weise C, Kleinstäuber M, Hesser H, Westin VZ, Andersson G. Acceptance of tinnitus: Validation of the tinnitus acceptance questionnaire. Cogn Behav Ther. 2013;42:100–15. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.781670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weise C, Hesser H, Andersson G, Nyenhuis N, Zastrutzki S, Kröner-Herwig B, et al. The role of catastrophizing in recent onset tinnitus: Its nature and association with tinnitus distress and medical utilization. Int J Audiol. 2013;52:177–88. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.752111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kröner-Herwig B, Jäger B, Goebel G. Weinheim: Beltz Psychologie Verlags Union; 2010. Tinnitus. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Manual; pp. 1–235. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hesser H, Weise C, Westin V, Andersson G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive-behavioral therapy for tinnitus distress. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:545–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moschen R, Riedl D, Schmidt A, Kumnig M, Bliem HR, Rumpold G. The development of chronic tinnitus in the course of a cognitive-behavioral group therapy. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2015;61:237–45. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2015.61.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hesser H, Westin VZ, Andersson G. Acceptance as a mediator in internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for tinnitus. J Behav Med. 2013;37:756–67. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry JA, Dennis KC, Schechter MA. General review of tinnitus: Prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48:1204–35. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/084). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes SC, Louma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal Z, Williams M, Teasdale J. New York: Guilford; 2002. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A new Approach to Preventing Relapse; pp. 1–392. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes SC, Pankey J. Acceptance. In: O’Donohue WT, Fisher JE, Hayes SC, editors. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Applying Empirically Supported Techniques in Your Practice. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons E-Book; 2004. pp. 1–624. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann SG, Asmundson GJ. Acceptance and mindfulness-based therapy: New wave or old hat? Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCracken LM, Vowles KE, Eccleston C. Acceptance of chronic pain: Component analysis and a revised assessment method. Pain. 2004;107:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moller AR. Similarities between severe tinnitus and chronic pain. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000;11:115–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreland JE. Leicester, England: University of Leicester; 2007. Illness Representations, Acceptance, Coping and Psychological Distress in Chronic Tinnitus; pp. 1–199. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moschen R, Schlatter A, Rumpold G, Schmidt A. Validation of the Chronic Tinnitus Acceptance Questionnaire (CTAQ) J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:650. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riedl D, Rumpold G, Schmidt A, Bliem HR, Moschen R. Acceptance of tinnitus: Validation of the ‛Akzeptanzfragebogen bei chronischem Tinnitus’ (AFCT) Laryngorhinootologie. 2014;93:840–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goebel G, Hiller W. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1998. Tinnitus-Fragebogen (TF). Ein Instrument zur Erfassung von Belastung und Schweregrad bei Tinnitus; pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallam RS. Manual of the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ) London: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franke G. Göttingen: Beltz; 2000. Brief Symptom Inventory von L.R. Derogatis (Kurzform der SCL-90-R) - Deutsche Version; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geisheim C, Hahlweg K, Fiegenbaum W, Frank M, Schröder B, von Witzleben I. German version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) as a tool for quality assurance in psychotherapy. Diagnostica. 2002;48:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand (SF 36) Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1998. pp. 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy JM, Berwick DM, Weinstein MC, Borus JF, Budman SH, Klerman GL. Performance of screening and diagnostic tests. Application of receiver operating characteristic analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:550–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wassertheil-Smoller S. A Primer für Health Professionals. New York: Spinger; 1990. Biostatistics and Epidemiology; pp. 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westin V, Ostergren R, Andersson G. The effects of acceptance versus thought suppression for dealing with the intrusiveness of tinnitus. Int J Audiol. 2008;47(Suppl 2):S112–8. doi: 10.1080/14992020802301688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baranoff J, Hanrahan SJ, Kapur D, Connor JP. Acceptance as a process variable in relation to catastrophizing in multidisciplinary pain treatment. Eur J Pain. 2013;17:101–10. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jastreboff PJ. Theory and Practice. London: Whurr; 1995. A neurophysiological Approach to Tinnitus. [Google Scholar]