Abstract

Purpose

We assessed whether changes in serial multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging can help predict the pathological progression of prostate cancer in men on active surveillance.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted of 49 consecutive men with Gleason 6 prostate cancer who underwent multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging at baseline and again more than 6 months later, each followed by a targeted prostate biopsy, between January 2011 and May 2015. We evaluated whether progression on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (an increase in index lesion suspicion score, increase in index lesion volume or decrease in index lesion apparent diffusion coefficient) could predict pathological progression (Gleason 3 + 4 or greater on subsequent biopsy, in systematic or targeted cores). Diagnostic performance of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging was determined with and without clinical data using a binary logistic regression model.

Results

The mean interval between baseline and followup multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging was 28.3 months (range 11 to 43). Pathological progression occurred in 19 patients (39%). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging was 37%, 90%, 69% and 70%, respectively. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.63. A logistic regression model using clinical information (maximum cancer core length greater than 3 mm on baseline biopsy or a prostate specific antigen density greater than 0.15 ng/ml2 at followup biopsy) had an AUC of 0.87 for predicting pathological progression. The addition of serial multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging data significantly improved the AUC to 0.91 (p = 0.044).

Conclusions

Serial multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging adds incremental value to prostate specific antigen density and baseline cancer core length for predicting Gleason 6 upgrading in men on active surveillance.

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging, prostatic neoplasms, watchful waiting

The majority of prostate cancer currently presents as localized disease and nearly half of cases are characterized as low grade.1 Thus, active surveillance has become an increasingly important management strategy, with the goal of avoiding unnecessary side effects associated with definitive therapy without missing the window for curative treatment, if necessary.

Serial prostate biopsy is a critical component of most contemporary AS regimens.2 The current standard of care is systematic, extended, sextant, 12-core transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy (systematic biopsy) which does not target specific lesions and, therefore, may under sample clinically significant disease.3 There is an unmet need for better noninvasive monitoring of men with PCa.

Multiparametric MRI provides a noninvasive means to assess the entire prostate gland from an anatomical and functional perspective. Findings on mpMRI are significant predictors of subsequent biopsy results.4,5 Therefore, mpMRI may be a useful adjunct in the followup of men on AS through detecting disease progression and through directing subsequent targeted biopsy. The value of mpMRI in the initial selection of men for AS is well established but the usefulness of serial mpMRI in the followup of men on AS has not yet been confirmed.6

Before serial mpMRI can be incorporated into AS regimens in a meaningful way, the 2 key questions that must be addressed are what is the natural history of mpMRI index lesions over time and what mpMRI findings constitute disease progression?7 Few studies to date have evaluated serial mpMRI findings in men with low risk PCa8–12 and these questions remain largely unanswered. In this study we assessed whether changes in serial mpMRI can help predict the pathological progression of PCa in men on AS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

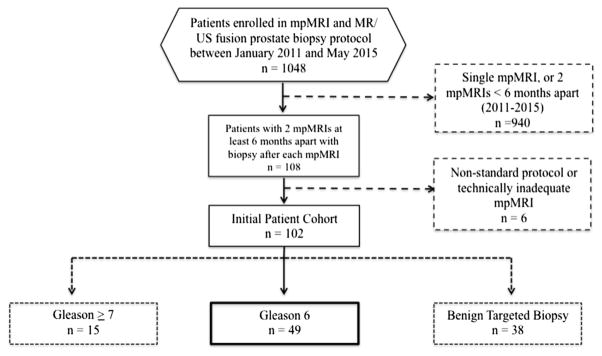

An institutional review board approved, HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliant review was performed on 1,048 consecutive men who underwent MR-US fusion guided prostate biopsy between January 2011 and May 2015. The current analysis is a retrospective review of a subset of these prospectively collected data. From this cohort 108 men with 2 or more mpMRI examinations at least 6 months apart, each followed by MR-US fusion biopsy, were identified. In men with more than 2 sets of serial mpMRI/MR-US fusion biopsy sessions, the first and last sets were selected. An additional 6 men were excluded from analysis due to nonroutine protocol on baseline or followup mpMRI, leaving 102 eligible men. Then 15 men were excluded due to Gleason 3 + 4 or greater on baseline MR-US fusion biopsy and 38 were excluded due to benign baseline biopsy, leaving a final cohort of 49 men with Gleason 6 PCa, who were enrolled in the UCLA AS program.6 Patients had serum PSA measurement at each MR-US fusion biopsy. Prostate volume was calculated using manual contouring of mpMRI examinations (fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for study inclusion

MRI Technique

Multiparametric MRI examinations were performed on a 3.0 T Siemens platform (Siemens MAGNETOM, Trio, Verio, Skyra or Prisma, Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, Pennsylvania) without an endorectal coil. The protocol included T2-weighted imaging, diffusion weighted imaging and dynamic contrast enhanced imaging.

Image Analysis

Image analysis was performed by 2 fellowship trained genitourinary radiologists (DJM, SSR), both of whom have interpreted more than 1,000 prostate mpMRIs. Radiologists were blinded to clinicopathological findings at the initial image interpretation. Each lesion was assigned a suspicion score, ranging from 1 (normal) to 5 (highly suspicious for PCa), using a previously published standardized assessment system.13

A third radiologist with 1 year of experience in prostate mpMRI (ERF) reviewed all studies quantitatively, and recorded volume and mean ADC for each lesion. Data analysis was performed on a DynaCAD workstation (Invivo, Gainesville, Florida).

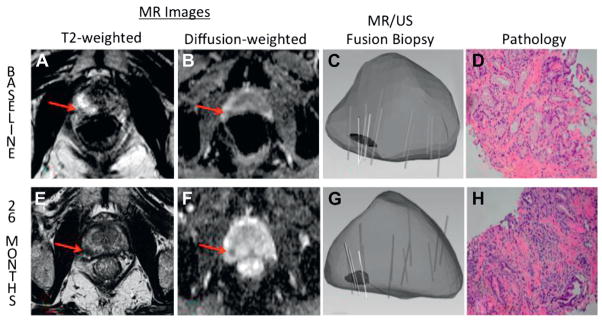

For each mpMRI examination the lesion with the highest overall suspicion score was selected as the index lesion. In cases where more than 1 lesion had the same suspicion score, the lesion with the lower mean ADC was selected as the index lesion, based on our previous work demonstrating that quantitative lesion ADC is an important predictor of Gleason score (fig. 2).14

Figure 2.

Example of progression of low grade prostate cancer in 65-year-old man on AS. At baseline axial T2-weighted image (A) demonstrates hypointense lesion in right apical peripheral zone. Diffusion weighted image (B) indicates ADC of 1,128. Overall suspicion score is 3. MR-US fusion biopsy (C ) revealed Gleason 3 + 3 PCa in target (D). After 26 months index lesion appears increased in size (E ) and ADC has decreased to 916 (F). Overall suspicion score of 4 was assigned. Repeat targeted biopsy (G) revealed Gleason 3 + 4 PCa (H ). Lesion fulfills 2 of 3 MRI progression criteria (increase in suspicion score and decrease in ADC).

MR-US Fusion Biopsy and Pathological Analysis

The reference standard in all cases was MR-US fusion biopsy using the Artemis device (Eigen, Grass Valley, California), which included systematic biopsy of 12 sites and additional targeted biopsy of any suspicious lesions identified on mpMRI.15 One core of tissue was obtained approximately every 3 mm along the longest diameter of each target, ie for a 9 mm target, 3 cores would be obtained. For targets exceeding 15 mm, a maximum of 5 cores was obtained. Patients were included regardless of whether Gleason 6 PCa was diagnosed on a targeted or a systematic core. Biopsy specimens were evaluated by a board certified genitourinary pathologist (JH). The maximum cancer core length was defined as the longest continuous length of cancer in any 1 biopsy core, systematic or targeted.

Study Design

Pathological progression was defined as an increase to Gleason score 3 + 4 or greater in any core, systematic or targeted. To test the hypothesis that changes in serial mpMRI examinations could predict pathological progression, a definition of MRI progression was devised. MRI progression was defined as an increase in index lesion suspicion score, a doubling of index lesion volume, or a decrease in index lesion ADC of 150 mm2 per second or greater on followup mpMRI.8 The ADC threshold of 150 mm2 per second was chosen using logistic regression analysis. Mean index lesion diameter in our study was 10.8 mm. Assuming the index lesion is roughly spherical, a doubling in index lesion volume would correspond to an approximately 3 mm increase in lesion diameter, which is consistent with the size thresholds used by other authors to constitute MRI progression.11,12

MRI progression was considered present if 1 or more of the previously mentioned criteria were satisfied. The performance of changes in serial mpMRI for predicting Gleason progression was evaluated with and without clinical data, including a PSAD threshold of 0.15 ng/ml2 at followup biopsy and a MCCL 3 mm or greater on baseline biopsy. A PSAD of 0.15 ng/ml2 or greater was chosen as the cutoff as it is the conventional upper limit for inclusion in most AS protocols.16 MCCL was evaluated as it has been shown to be a reasonable surrogate for tumor volume.17 Using logistic regression analysis we found that a baseline MCCL of 3 mm or greater was the optimal threshold to predict pathological progression.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics and clinical data were reported using descriptive statistics. mpMRI features were compared between men who had pathological progression and men who did not. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive value of changes in serial mpMRI. Multivariate logistic regression was also used to evaluate the relationships among MRI progression, clinical variables and pathological progression. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were calculated, with p <0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Clinical Features

The final patient cohort consisted of 49 patients. Mean patient age was 65 years (range 47 to 80). Median PSA was 5 ng/ml (IQR 2.5–6.4, range 0.51 to 15). Additional patient demographics and clinical features are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics at baseline

| Mean pt age (SD) | 65.4 (8.0) |

| Median ng/ml PSA (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0) |

| Median cm3 prostate vol (IQR) | 50.0 (29.3) |

| Mean ng/ml2 PSAD (SD) | 0.10 (0.08) |

| No. race (%): | |

| Caucasian | 41 (84) |

| African-American | 3 (6) |

| Hispanic | 3 (6) |

| Asian | 2 (4) |

Initial MR-US Fusion Biopsy

An index lesion was identified in all but 1 of the initial 49 mpMRI examinations.Ofthese index lesions 9 (19%) were classified as low suspicion (grade 2), 26 (53%) were moderate suspicion (grade 3), 11 (23%) were high suspicion (grade 4) and 2 (4%) were extremely suspicious (grade 5). Quantitative index lesion features are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline mpMRI and MR-US fusion biopsy findings

| Mean lesions on mpMR1 (SD) | 1.65 (0.78) |

| No. index lesion suspicion score on mpMRI (%):13 | |

| 1 (very low suspicion) | 1 (2) |

| 2 (low suspicion) | 9 (18.4) |

| 3 (moderate suspicion) | 26 (53.1) |

| 4 (high suspicion) | 11 (22.4) |

| 5 (extremely high suspicion) | 2 (4.1) |

| Mean cm3 index lesion vol (SD) | 0.26 (0.21) |

| Mean mm index lesion diameter (SD) | 10.8 (3.6) |

| Mean mm2/sec index lesion ADC (SD) | 1,050 (192) |

| Mean targeted biopsy cores/pt (SD) | 3.4 (1.1) |

| Mean systematic biopsy cores/pt (SD) | 11.8 (2.4) |

| Mean total Ca core length/pt (SD) | 2.32 (1.89) |

Followup mpMRI and MR-US Fusion Biopsy

The mean interval between baseline and followup mpMRI was 28.3 months (range 11 to 43). Of the 48 men with an index lesion identified on baseline mpMRI, in 33 (67%) the same index lesion was present on the subsequent mpMRI. In the remaining 15 men (33%) the original index lesion was no longer identifiable as a discrete lesion or was considered at most to have very low suspicion for PCa (grade 1). Overall 19 men (39%) had pathological progression, with 17 (89%) demonstrating progression to Gleason 3 + 4 and 2 (11%) demonstrating progression to Gleason greater than 3 + 4. Pathological progression was demonstrated on targeted biopsy in 9 patients (47%), on systematic biopsy in 7 (37%), and on systematic and targeted biopsy in 3 (16%).

Overall 10 patients had mpMRI progression, including 2 patients with an increase in index lesion suspicion score, 1 with a doubling of index lesion volume, 3 with a decrease in index lesion ADC 150 mm2 per second or greater and 4 with a combination thereof. Of the 10 men with MRI progression 7 also demonstrated pathological progression on followup biopsy (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline and followup mpMRI findings

| Initial mpMRI | Subsequent mpMRI | |

|---|---|---|

| No. index lesions present (% of total) | 48 (98) | 33 (67) |

| Mean cm3 index lesion vol (SD) | 0.26 (0.21) | 0.28 (0.22) |

| Mean mm2/sec index lesion ADC (SD) | 1,050 (192) | 1,063 (217) |

| No. mpMRI progression (% of total): | – | 10 (20) |

| Suspicion score increase | – | 2 (20) |

| Index lesion vol increase | – | 1 (10) |

| Index lesion ADC decrease | – | 3 (30) |

| More than 1 MRI progression feature | 4 (40) |

Performance of Serial mpMRI for Predicting Pathological Progression

Differences in patient demographics, clinical features and mpMRI findings between patients with pathological progression and those without are presented in table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of clinical and mpMRI findings in men without and with pathological progression

| No Pathological Progression

|

Pathological Progression

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Quartile 25 | Quartile 75 | Median | Quartile 25 | Quartile 75 | p Value | |

| Age | 62 | 54 | 68 | 65 | 58 | 68 | 0.211 |

| PSA (ng/ml) | 4 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 3 | 11.2 | 0.017 |

| Prostate vol (cm3) | 55 | 41 | 74 | 42 | 34 | 60 | 0.046 |

| PSAD (ng/ml2) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.001 |

| Change in PSAD | 0.002 | − 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.001 |

| Baseline MCCL | 1.15 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0.019 |

| Change in index lesion vol | 0.005 | − 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.05 | − 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.061 |

| Change in index lesion ADC | − 8 (decrease) | − 64 (no change) | 197 (increase) | − 65 (decrease) | − 134 (no change) | 37 (increase) | 0.065 |

| Change in suspicion score (No.) | 18 (60) | 10 (33.3) | 2 (6.7) | 5 (26) | 10 (53) | 4 (21) | |

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of mpMRI alone for predicting pathological progression was 37%, 90%, 69% and 70%, respectively. AUC was 0.63.

The performance of baseline MCCL and PSAD at subsequent biopsy for predicting pathological progression is presented in table 5. A logistic regression model combining these 2 clinical features (MCCL 3 mm or greater at baseline biopsy or PSAD 0.15 ng/ml2 or greater at followup biopsy) yielded an AUC of 0.87 for the prediction of pathological progression.

Table 5.

Performance of mpMRI score and clinical data for prediction of pathological progression

| Performance | mpMRI Progression | MCCL 3 mm or Greater (baseline) | PSAD 0.15 ng/ml2or Greater (follow up) | Any Condition Met |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Sensitivity (95% CI) | 37 (16–62) | 53 (29–76) | 63 (38–84) | 95 (74–99) |

| % Specificity (95% CI) | 90 (74–98) | 80 (61–92) | 97 (83–99) | 70 (51–85) |

| % PPV (95% CI) | 69 (52–83) | 63 (35–85) | 92 (64–99) | 67 (46–84) |

| % NPV (95% CI) | 70 (34–93) | 73 (55–87) | 81 (64–92) | 96 (77–99) |

| % Accuracy (95% CI) | 69 (55–82) | 69 (55–82) | 84 (70–93) | 80 (66–90) |

| OR (95% CI) | 5.3 (1.2–22) | 4.4 (1.3–15.4) | 50 (7–448) | 42 (6–364) |

| AUC | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.80 | 0.91 |

Of the 19 patients with pathological progression 2 had progression detected solely on the basis of serial mpMRI findings. The addition of serial mpMRI data to the logistic regression model significantly improved the AUC to 0.91 (p = 0.044).

DISCUSSION

The widespread adoption of PSA screening in the United States has led to a fundamental shift in PCa diagnosis toward men with low risk disease.18 There is growing acceptance of active surveillance as a viable treatment strategy for many of these men. Most contemporary AS protocols call for periodic biopsy, conventionally performed in a blind fashion using ultrasound guidance. If proven to be an accurate indicator of prostate pathology, mpMRI might be an attractive alternative for noninvasive monitoring of men on AS.

Thus, we evaluated the potential role for serial mpMRI examinations in predicting reclassification in a cohort of men on AS for low risk PCa, using an index lesion based analysis. We selected this approach because many prior studies have demonstrated that the index lesion drives pathological progression of PCa and that mpMRI can reliably localize the site of the index lesion.19,20 Using the index lesion based approach we created a mpMRI definition of disease progression, which included an increase in index lesion suspicion score, decrease in index lesion ADC and increase in index lesion volume.

Similar to previous authors,10,11 we observed a high specificity of changes in serial mpMRI (90%) but a low sensitivity (37%) for predicting pathological progression. This is not unexpected because the relationship of mpMRI findings to underlying pathology has not yet been fully clarified. Additionally, some PCa is not visible or shows poor conspicuity on mpMRI, due in part to variable histological architecture.21 To investigate whether mpMRI contributes significant incremental information to conventional clinical data, we performed logistic regression analysis using clinical data with and without serial mpMRI. The addition of serial mpMRI significantly improved the performance of the logistic regression model, suggesting that mpMRI contributes unique information about the likelihood of PCa progression. Although the relative improvement over conventional clinical data achieved with the addition of mpMRI was relatively small, it is important to note that the baseline MCCL was also influenced by mpMRI, as it was obtained via a MRI targeted biopsy. Therefore, the true incremental value of mpMRI is likely somewhat higher than reported here.

Rosenkrantz et al evaluated the association between changes in suspicious prostate lesions on serial MRI and followup biopsy results in 55 patients.11 As in our study, they observed a low sensitivity (23% to 35%) of MRI for predicting positive followup biopsy results but a high specificity (76% to 90%). Mean followup in their study was only 14 months and the majority of patients did not have known PCa at the initial mpMRI. In another of the largest series to date, Walton Diaz et al evaluated the use of serial mpMRI and MR-US fusion biopsy in the treatment of patients on AS.10 The authors evaluated 58 patients on AS and concluded that the combination of mpMRI and MR-US fusion biopsy appears promising as an aid for decreasing the number of serial biopsies among patients on AS. Median followup in their study was only 16 months. Unlike these prior studies, we evaluated index lesion size using volume, not diameter. Obtaining an accurate measurement of prostate lesion size is challenging because prostate tumors do not usually form discrete masses with clear margins. Therefore, we elected to measure volume because it allows measurement over several slices and improved quantification.

The combination of serial mpMRI data with PSAD and MCCL was used in this study to predict the pathological progression of PCa in men on AS. The PSAD threshold of 0.15 ng/ml2 was established as an important cut point by Epstein et al in 1994 and has been widely confirmed.16 The MCCL threshold of 3 mm or greater on baseline biopsy was derived using logistic regression analysis and closely mirrors that recently reported by Ahmed et al, who found that a MCCL of 4 mm or greater was an optimal threshold for characterizing clinically significant PCa.22

Our study has several limitations. In addition to its retrospective nature, the sample size was relatively small. Inclusion criteria were limited to men with Gleason 6 PCa and results may not apply to men with low volume secondary pattern 4 disease, some of whom are now being included on AS. Although the followup interval of 28 months is significantly longer than that reported in prior similar studies, it still may not have been long enough to capture additional cases of PCa which ultimately would have shown progression. Nonetheless, as systematic biopsy is currently being performed annually in most patients on AS, the study period was long enough to generate clinically relevant data for this population. In addition, as we used an index lesion based analysis and secondary or satellite lesions were not systematically assessed, it is possible that with time some of these lesions could contribute to pathological progression. Because our study population was limited to men with positive baseline MR-US fusion targeted biopsies, the prevalence of suspicious findings on mpMRI is likely higher than would be observed in men enrolled in AS based on a conventional systematic biopsy.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that mpMRI stability along with supportive PSAD (less than 0.15 ng/ml2 at followup) and low volume PCa at baseline (less than 3 mm MCCL) can be used to define a group of men with very low risk PCa in whom pathological progression is very unlikely, such that repeat prostate biopsy may be deferred. Larger, prospective studies will be necessary to validate these findings.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Award Number R01CA158627 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by UCLA Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Grant No. UL1TR000124, the Beckman Coulter Foundation, the Jean Perkins Foundation and the Steven C. Gordon Family Foundation.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ADC

apparent diffusion coefficient

- AS

active surveillance

- MCCL

maximum cancer core length

- mpMRI

multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MR-US

magnetic resonance-ultrasound

- NPV

negative predictive value

- PCa

prostate cancer

- PPV

positive predictive value

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- PSAD

PSA density

Footnotes

No direct or indirect commercial incentive associated with publishing this article.

The corresponding author certifies that, when applicable, a statement(s) has been included in the manuscript documenting institutional review board, ethics committee or ethical review board study approval; principles of Helsinki Declaration were followed in lieu of formal ethics committee approval; institutional animal care and use committee approval; all human subjects provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality; IRB approved protocol number; animal approved project number.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filson CP, Marks LS, Litwin MS. Expectant management for men with early stage prostate cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:264. doi: 10.3322/caac.21278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berglund RK, Masterson TA, Vora KC, et al. Pathological upgrading and up staging with immediate repeat biopsy in patients eligible for active surveillance. J Urol. 2008;180:1964. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinto PA, Chung PH, Rastinehad AR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy improves cancer detection following transrectal ultrasound biopsy and correlates with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2011;186:1281. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.05.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vourganti S, Rastinehad A, Yerram NK, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound fusion biopsy detect prostate cancer in patients with prior negative transrectal ultrasound biopsies. J Urol. 2012;188:2152. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu JC, Chang E, Natarajan S, et al. Targeted prostate biopsy in select men for active surveillance: do the Epstein criteria still apply? J Urol. 2014;192:385. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore CM, Petrides N, Emberton M. Can MRI replace serial biopsies in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer? Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24:280. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonekamp D, Bonekamp S, Mullins JK, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging characterization of prostate lesions in the active surveillance population: incremental value of magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of disease reclassification. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2013;37:948. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31829ae20a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rais-Bahrami S, Türkbey B, Rastinehad AR, et al. Natural history of small index lesions suspicious for prostate cancer on multiparametric MRI: recommendations for interval imaging follow-up. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2014;20:293. doi: 10.5152/dir.2014.13319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walton Diaz A, Shakir NA, George AK, et al. Use of serial multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in the management of patients with prostate cancer on active surveillance. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:202. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenkrantz AB, Rice SL, Wehrli NE, et al. Association between changes in suspicious prostate lesions on serial MRI examinations and follow-up biopsy results. Clin Imaging. 2015;39:264. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryk DJ, Llukani E, Huang WC, et al. Natural history of pathologically benign cancer suspicious regions on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging following targeted biopsy. J Urol. 2015;194:1234. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonn GA, Natarajan S, Margolis DJ, et al. Targeted biopsy in the detection of prostate cancer using an office based magnetic resonance ultrasound fusion device. J Urol. 2013;189:86. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamrava M, Chung M, Mesko S, et al. Correlation of quantitative diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI parameters with NCCN risk group, Gleason score, and maximum tumor diameter in prostate cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol, suppl. 2013;3:S4. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natarajan S, Marks LS, Margolis DJ, et al. Clinical application of a 3D ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy system. Urol Oncol. 2011;29:334. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, et al. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA. 1994;271:368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsugasumi T, Baco E, Palmer S, et al. Prostate cancer volume estimation by combining magnetic resonance imaging and targeted biopsy proven cancer core length: correlation with cancer volume. J Urol. 2015;194:957. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3669. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter HB, Partin AW, Walsh PC, et al. Gleason score 6 adenocarcinoma: should it be labeled as cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baco E, Ukimura O, Rud E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound image-fusion biopsies accurately characterize the index tumor: correlation with step-sectioned radical prostatectomy specimens in 135 patients. Eur Urol. 2015;67:787. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langer DL, van der Kwast TH, Evans AJ, et al. Intermixed normal tissue within prostate cancer: effect on MR imaging measurements of apparent diffusion coefficient and T2–sparse versus dense cancers. Radiology. 2008;249:900. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2493080236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed HU, Hu Y, Carter T, et al. Characterizing clinically significant prostate cancer using template prostate mapping biopsy. J Urol. 2011;186:458. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]