Abstract

Due to its rarity, experience with pregnancy in Budd–Chiari syndrome (BCS) is limited. With the advent of new treatment modalities, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in particular, numbers of affected women seeking pregnancy with BCS are expected to rise. Here, we use a case that ended lethal within 2 years after delivery to discuss the effect of pregnancy on BCS and vice versa, and to highlight the necessity of a multidisciplinary teamwork. Additionally, a risk classification is proposed which may serve as a framework for preconception counseling and assist in the establishment and evaluation of treatment algorithms; its criteria need to be defined and assessed for their applicability in further studies.

INTRODUCTION

Budd–Chiari syndrome (BCS) is defined as obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow. This obstruction might be located anywhere between the small hepatic veins to the suprahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC).1 The typical patient is a young woman presenting with abdominal pain, ascites, and hepatomegaly; however, the clinical presentation varies. Usually patients show an underlying prothrombotic disorder, and in a substantial number of patients several risk factors are found.2 The disease is mainly diagnosed by imaging, whereas therapeutic options comprise a step-wise approach with medication (anticoagulation), minimally invasive procedures such as thrombolysis, percutaneous angioplasty, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS), but also surgical portosystemic shunting, and orthotopic liver transplantation (LTX). BCS is a rare disease but a clinical challenge. Moreover, pregnancy in women with BCS is extremely rare; pregnancy exerts a detrimental effect on the course of the disease. Here we report the case of a patient with BCS due to essential thrombocythemia (ET) and TIPS which ended lethal within 19 months after delivery. The manuscript was written after the patient's death. The University Bonn Medical School Ethics committee allows publication without consent in such cases. Additionally, we propose a score for risk classification of pregnancy in women with pre-existing BCS.

CASE

At the age of 16, essential thrombocythemia was diagnosed (JAK2V617K negative). A stable course of disease could be achieved for 8 years by treatment with hydroxyurea, when acute BCS occurred with occlusion of all liver veins. Treatment consisted of lysis and veno-venous shunt (Palmaz-stent) placement between left hepatic vein and IVC at a regional hospital (Figure 1) in conjunction with anticoagulant treatment using the vitamin K-antagonist (VKA) phenprocoumon. She remained stable for the subsequent 12 years with well-controlled hematologic disease and without thrombotic or portal hypertensive complications. At 36 years of age, progressive, recurrent ascites developed which was treated by creating a new TIPS using a baremetal and a covered stent.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Invasive portography after left-sided TIPS placement demonstrating patent TIPS perfusion. (B, C) Invasive TIPS-control demonstrating cavernous transformed portal occlusion and restored hepatopetal flow after TIPS elongation: (1) main portal vein; (2) left portal vein; (3) left hepatic vein. TIPS = transjugular portosystemic shunt.

This TIPS-tract was created from the ostium of the left liver vein, very close to the end of the Palmaz-stent and the left portal vein branch. The pressure gradient dropped >50% (portosystemic gradient decrease from 36 to 15 mm Hg, see Figure 1A), as usual during TIPS insertion.3–5 In the follow-up visits, the TIPS was patent and there was no need for invasive measurements until the patient conceived. One year after TIPS revision, at the age of 38, the patient conceived. During pregnancy, close interdisciplinary care was established. VKA anticoagulation was replaced by therapeutic dose of the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) enoxaparin with regular monitoring of anti-FXa (aXa) activity (peak aXa-level: 1.0 – 1.2 U/mL), and hydroxyurea was discontinued due to its teratogeneity. Even though the recommendation in patients with high-risk ET is to use interferon-alpha (evidence level III and Grade B), we advised against it, as there are no controlled studies which show a clear benefit regarding teratogeneity, and, in particular, there is no experience in the situation of BCS.6 TIPS patency was examined 4-weekly using Doppler-ultrasound; small amounts of ascites were first detected at a gestational age (GA) of 12 weeks. First- and second-trimester ultrasound examinations including echocardiography and Doppler examination of the fetal and uterine vessels were unremarkable. Platelet numbers were within the upper normal range (500–680 G/L). Despite aXa-adjusted anticoagulation within the therapeutic range (enoxaparin 60 mg qam, 80 mg qhs), thrombosis of the right subclavian vein occurred at GA 25.

Therefore, testing for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) typical antibodies was performed, and medication was changed to fondaparinux (5 mg bd), as the anticoagulant and antithrombotic efficacy of fondaparinux at this dosage is superior. A gradual deterioration of her general condition occurred; she complained of increasing abdominal distension, pain, and dyspnea. Although TIPS was patent at every control, recurrent paracenteses (overall volume 15.4 L) had to be performed to relieve these symptoms. Serial ultrasound of the uterine cervix revealed progressive shortening, prompting tocolytic therapy with atosiban and administration of corticosteroids for acceleration of fetal pulmonary maturity at 28 weeks of gestation. At GA 28 + 2, abnormal fetal heart rate tracings and progressive cervical dilatation necessitated cesarean delivery, which was performed under general anesthesia. Anticoagulation was switched to unfractioned heparin for perioperative bridging. An apparently healthy girl was born (1205 g, 64. percentile, Apgar 8/9/10, arterial pH 7.34) and transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit. The estimated blood loss was 400 mL. Operation and postoperative surgical course was unremarkable; several litres of ascites were drained after abdominal incision. The newborn had to undergo emergency laparotomy on day 1 for gastric perforation. The further course was uncomplicated, and the baby was discharged home 8 weeks later.

Post partum, ascites, and upper abdominal pain worsened despite continuous ascites drainage and medication. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was therefore performed on postoperative day 4, which revealed grade II esophageal and grade I gastric varices. Therefore, TIPS dysfunction was suspected. Invasive TIPS-control demonstrated a foreshortening of the uncovered stent at the portal segment with associated cavernous transformed portal venous thrombosis. Subsequently, a covered stent elongation to a big portal varice was performed (portosystemic gradient decreased from 12 to 6 mm Hg, see Figure 1B and C). Thereafter, the patient was stable on treatment with hydroxyurea and fondaparinux; the latter was switched to rivaroxaban 2 weeks postpartum. Five months later TIPS reocclusion was diagnosed (see Figure 2). This may have occurred as a result of severe thrombocytosis (1541 G/L), which deteriorated despite treatment. This time a TIPS revision with an adequate lowering of porto-systemic pressure gradient was not expected; therefore, a spleno-renal shunt was created in order to treat the complications of portal hypertension (see Figure 3A). However, within the course of the following weeks, the patient developed several flares of ET with platelets around 800 G/L despite treatment. When renal dysfunction was present as hepatorenal syndrome, she was listed for LTX 3 months later (initial model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)-score 28 plus special request for Non-Standard Exception [NSE]). Bone marrow transplantation to cure ET was discussed; however, the patient did not fulfill the criteria. During this time, the liver function deteriorated, and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a >7 cm measuring central “tumor,” which turned out to be a necrotic BCS-nodule (see Figure 3B). An organ allocation for LTX was finally achieved 19 months after delivery. Unfortunately, the postoperative course was complicated by a primary nonfunction (PNF) of the first graft, and despite double retransplantation the patient succumbed 2 weeks later.

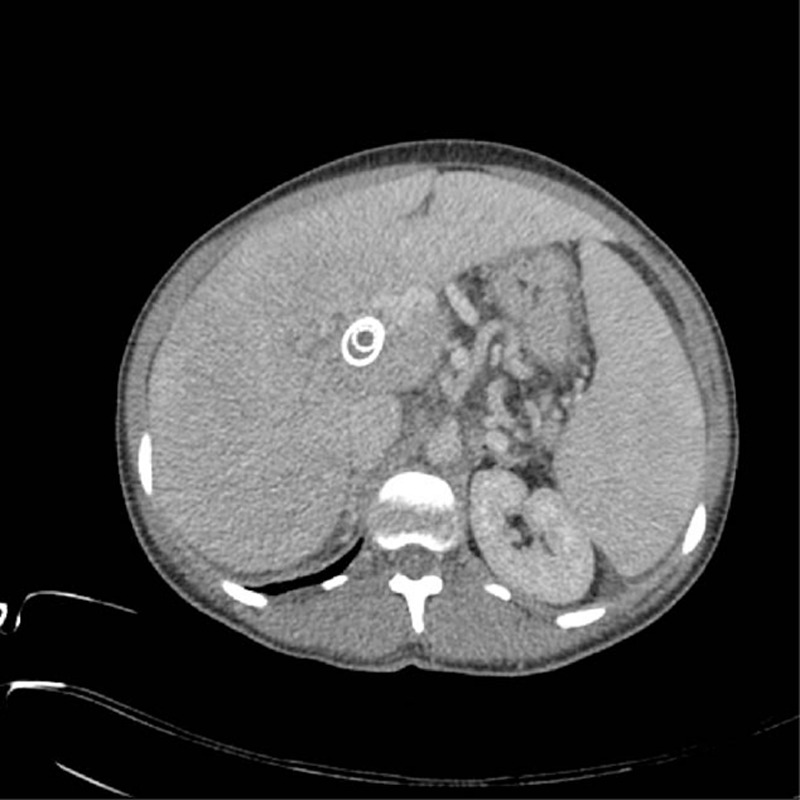

FIGURE 2.

CT scan demonstrating stent in stent configuration and TIPS reocclusion. CT = computed tomography, TIPS = transjugular portosystemic shunt.

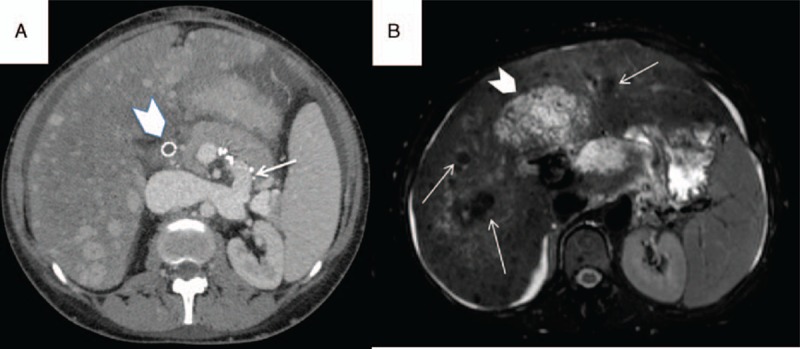

FIGURE 3.

(A) CT scan demonstrating occluded TIPS (arrowhead), patent splenorenal shunt (arrow), and cirrhotic liver disease with multiple regenerative nodules. (B) Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed MR image demonstrating a cirrhotic liver with siderotic nodules (arrows) and massive central liver fibrosis with edema (arrowhead). CT = computed tomography, MR = magnetic resonance, TIPS = transjugular portosystemic shunt.

DISCUSSION

With a prevalence of 1 in 100.000 to 500.000,7,8 primary BCS is a rare disorder. Characterized by abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, and ascites, the temporal dynamics, site, and extent of obstruction determine its clinical course.2,9,10 Predisposing factors include, among others, inherited or acquired hypercoagulability and especially myeloproliferative diseases, as in our case.11 Pregnancy itself is also a risk factor for BCS; however, usually additional risk factors are present.12 With a 3-year-lethality of 90%, untreated BCS has a dismal prognosis.8 Due to the paucity of data, treatment is based on expert consensus and consists of anticoagulation, interventional angioplasty, or TIPS stent with the aim to decompress the portal venous compartment. If these treatments fail, LTX remains as the last resort.1,7,10,13

In addition to the pregnancy-induced hypercoagulability, several changes inherent to pregnancy add to its detrimental effect on BCS. These include blood volume expansion and hypoproteinemia; the rise in intraabdominal pressure; pressure of the gravid uterus on the IVC and other intraabdominal vessels, including the lymphatic system; and the displacement of intraabdominal organs by the expanding uterus, causing changes in their respective anatomical relationship.14–16 The occurrence of thrombosis despite full-dose and aXa-adjusted anticoagulant treatment underscores the high thrombotic risk of ET patients during pregnancy.

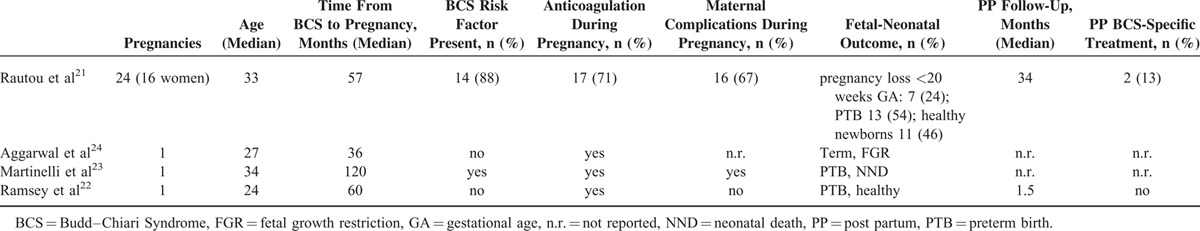

Historical case series on BCS and pregnancy, reporting a 1-year maternal mortality of 50%17 are not suitable for risk assessment due to the advent of additional treatment modalities, in particular TIPS.18–20 Contemporary reports on pregnancy in BCS (from 1990 onwards) are restricted to 1 small series21 and 3 case reports.22–24 Details are listed in Table 1. Overall, 27 pregnancies in 19 women with pre-existing BCS are described. Even though there was no maternal mortality during pregnancy, delivery and follow-up, morbidity was considerable, including thrombosis, hemorrhage, and TIPS occlusion. Likewise, fetal-neonatal outcome was poor, with a high rate of pregnancy losses and preterm births.

TABLE 1.

Reports of Pregnancy in Women With Pre-existing Budd–Chiari Syndrome

We cannot prove that the detrimental course of the disease could have been avoided if the patient had abstained from pregnancy. The long time intervals with stable disease and the rapid downward trend during pregnancy and after delivery, however, point to a relevant contribution of pregnancy to the lethal course.

In women with pre-existing cardiac disease, a classification has been developed, which is based on disease severity and anticipated impact of pregnancy on the underlying condition.25,26 It allows the attending physician risk assessment, preconception counseling, and risk-adapted care during pregnancy and childbirth. In analogy, we suggest the classification of BCS into World Health Organization (WHO) Classes I to IV as follows:

Class 1: maternal mortality not increased; no or only slight increase in maternal morbidity.

Class 2: maternal mortality slightly increased; maternal morbidity moderately increased.

Class 3: maternal mortality significantly increased; severe maternal morbidity. Interdisciplinary management before, during, and after pregnancy is mandatory.

Class 4: extremely high maternal mortality, high risk of severe morbidity. Pregnancy is contraindicated, termination should be considered. In the case of continuation of pregnancy, management as for class 3 is required.

Allocation criteria may include the following:

General: age; time between diagnosis and pregnancy.

History: presence and type of prothrombotic factors; number of thrombosed veins; complications of portal hypertension; type and number of previous interventions.

Clinical findings: ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, esophageal varices; cholangiopathy.

Laboratory results: liver function, kidney function, infection, coagulation.

Diagnostic imaging: IVC obstruction, collaterals.

Rotterdam, international prognostic score of thrombosis in World Health Organization-essential thrombocythemia (IPSET) or other scores.7,27

The usefulness of these and additional criteria, however, needs to be established.7,27 With numbers of women with BCS seeking pregnancy expected to rise, the scoring system may help in preconception risk assessment and counseling; furthermore, it may support in the establishment of treatment algorithms of BCS in pregnancy.

Notwithstanding that, a favorable outcome of pregnancy in women with BCS requires an interdisciplinary team of specialists in gastroenterology, radiology, visceral surgery, hemostaseology, fetal medicine, obstetrics, and neonatology. More data are needed to adequately manage these challenging cases.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: aXa = anti-Factor Xa, BCS = Budd–Chiari Syndrome, ET = essential thrombocythemia, GA = gestational age, HIT = heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, IPSET = international prognostic score of thrombosis in World Health Organization-essential thrombocythemia, IVC = inferior vena cava, LMWH = low-molecular-weight heparin, LTX = orthotopic liver transplantation, MELD = model for end-stage liver disease, NSE = nonstandard exception, PNF = primary nonfunction, TIPS = transjugular portosystemic shunt, VKA = vitamin K antagonists, WHO = World Health Organization.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Franchis R. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2015; 63:743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darwish Murad S, Plessier A, Hernandez-Guerra M, et al. Etiology, management, and outcome of the Budd–Chiari syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berres ML, Lehmann J, Jansen C, et al. Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 levels predict survival in cirrhotic patients with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Liver Int 2016; 36:386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauerbruch T, Mengel M, Dollinger M, et al. Prevention of rebleeding from esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis receiving small-diameter stents versus hemodynamically controlled medical therapy. Gastroenterology 2015; 149:660–668.e661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berres M-L, Asmacher S, Lehmann J, et al. CXCL9 is a prognostic marker in patients with liver cirrhosis receiving transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. J Hepatol 2015; 62:332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison CN, Bareford D, Butt N, et al. Guideline for investigation and management of adults and children presenting with a thrombocytosis. Br J Haematol 2010; 149:352–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murad SD, Valla D-C, de Groen PC, et al. Determinants of survival and the effect of portosystemic shunting in patients with Budd–Chiari syndrome. Hepatology 2004; 39:500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valla DC. Primary Budd–Chiari syndrome. J Hepatol 2009; 50:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen HL, Garcia-Pagan JC, Elias E, et al. Budd–Chiari syndrome: a review by an expert panel. J Hepatol 2003; 38:364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seijo S, Plessier A, Hoekstra J, et al. Good long-term outcome of Budd–Chiari syndrome with a step-wise management. Hepatology 2013; 57:1962–1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smalberg JH, Koehler E, Darwish Murad S, et al. The JAK2 46/1 haplotype in Budd–Chiari syndrome and portal vein thrombosis. Blood 2011; 117:3968–3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rautou PE, Plessier A, Bernuau J, et al. Pregnancy: a risk factor for Budd–Chiari syndrome? Gut 2009; 58:606–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancuso A. An update on management of Budd–Chiari syndrome. Ann Hepatol 2014; 13:323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chun R, Kirkpatrick AW. Intra-abdominal pressure, intra-abdominal hypertension, and pregnancy: a review. Ann Intensive Care 2012; 2 Suppl 1:S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs F, Bruyere M, Senat MV, et al. Are standard intra-abdominal pressure values different during pregnancy? PLoS One 2013; 8:e77324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bissonnette J, Durand F, de Raucourt E, et al. Pregnancy and vascular liver disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2015; 5:41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khuroo MS, Datta DV. Budd–Chiari syndrome following pregnancy. Report of 16 cases, with roentgenologic, hemodynamic and histologic studies of the hepatic outflow tract. Am J Med 1980; 68:113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eapen CE, Velissaris D, Heydtmann M, et al. Favourable medium term outcome following hepatic vein recanalisation and/or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for Budd Chiari syndrome. Gut 2006; 55:878–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Pagan JC, Heydtmann M, Raffa S, et al. TIPS for Budd–Chiari syndrome: long-term results and prognostics factors in 124 patients. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:808–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rössle M. TIPS: 25 years later. J Hepatol 2013; 59:1081–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rautou PE, Angermayr B, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. Pregnancy in women with known and treated Budd–Chiari syndrome: maternal and fetal outcomes. J Hepatol 2009; 51:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsey PS, Hay JE, Ramin KD. Successful pregnancy following orthotopic liver transplantation for idiopathic Budd–Chiari syndrome. J Matern Fetal Med 1998; 7:235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinelli P, Maruotti GM, Coppola A, et al. Pregnancy in a woman with a history of Budd–Chiari syndrome treated by porto-systemic shunt, protein C deficiency and bicornuate uterus. Thromb Haemost 2006; 95:1033–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aggarwal N, Suri V, Chopra S, et al. Pregnancy outcome in Budd Chiari Syndrome—a tertiary care centre experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013; 288:949–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Blomstrom Lundqvist C, Borghi C, et al. ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011; 32:3147–3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorne S, MacGregor A, Nelson-Piercy C. Risks of contraception and pregnancy in heart disease. Heart 2006; 92:1520–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbui T, Finazzi G, Carobbio A, et al. Development and validation of an International Prognostic Score of thrombosis in World Health Organization-essential thrombocythemia (IPSET-thrombosis). Blood 2012; 120:5128–5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]