Abstract

Introduction Congenital umbilical arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are extremely rare. We present the first case of congenital umbilical AVM with feeding arteries originating not only from abdominal but also from the mammary arteries.

Case Report A 34-week gestational age newborn was transferred to our hospital with a supraumbilical murmur. Abdominal Doppler ultrasound (US) showed a large vascular AVM, with multiple feeding arteries and several venous drainage structures to the umbilical vein and also a persistent ductus venosus. She developed signs of heart failure on the 12th day of life. Computed tomography angiogram revealed an umbilical congenital AVM with feeding arteries originating from the external iliac, hypogastric, epigastric, and mammary arteries and a dilated umbilical vein draining the cluster. Also, a patent ductus venosus was observed. At 14 days of life, laparotomy was performed but due to the complexity of the feeding arteries of the AVM, complete exeresis was not performed, but only ligation of these arteries was made, to reduce the surgical risk.

Conclusion To our knowledge, this is the first time that no complete excision was made but only ligation of the arteries. The infant was discharged home on postoperative day 14 being asymptomatic. Follow-up Doppler US showed thrombosed vascular structures.

Keywords: arteriovenous malformation, congenital, high-output cardiac failure, newborn

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are congenital lesions consisting in a tangle of arteries and veins connected by one or more fistulae. Congenital AVMs are found most commonly in the brain, liver, and extremities. Congenital umbilical AVMs are extremely rare; to our knowledge less than 10 cases have been described. This kind of malformations can generate a wide clinical spectrum, from being asymptomatic up to congestive heart failure and massive hemorrhagic shock. We present the first case of congenital umbilical AVM with feeding arteries originating not only from abdominal but also from mammary arteries.

Case Report

A 34-week 2-day gestational age newborn, female, 3 days old, 1,660 g birth weight, born by emergency cesarean section because of abruptio placentae from an uneventful pregnancy was transferred to our hospital because of feeding intolerance and supraumbilical murmur, which was diagnosed initially as a portocaval shunt.

Physical examination at admission was unremarkable except for a murmur at the lower area of the abdomen, but palpation did not identify any mass in that area, and the umbilicus had also normal appearance. No other malformations were found.

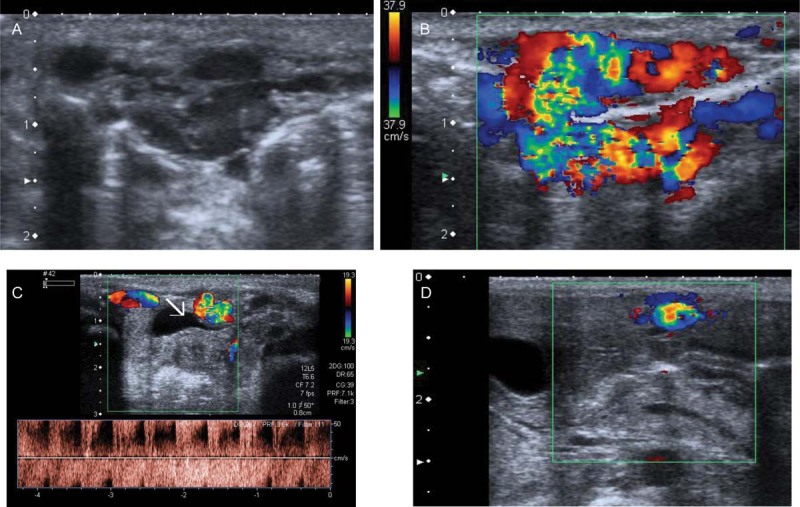

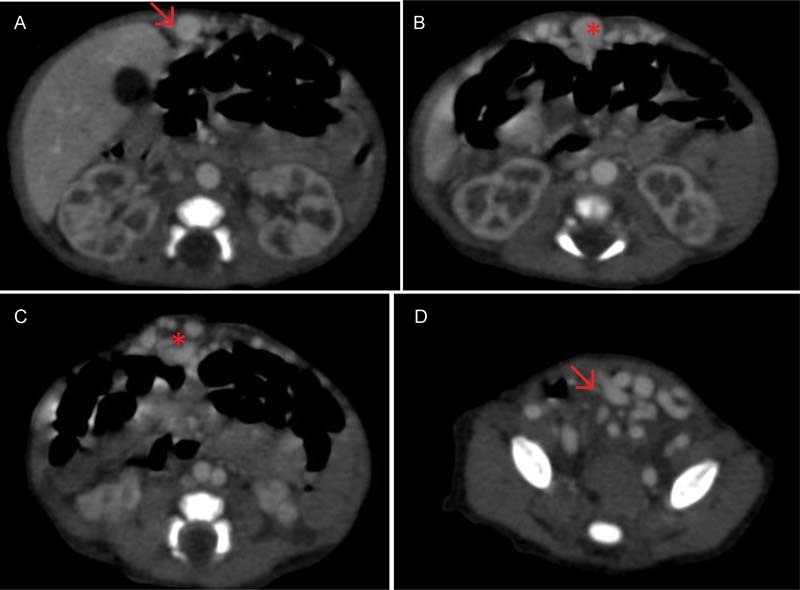

After admission, an abdominal Doppler ultrasound (US) (Fig. 1) showed a large vascular AVM (28.5 × 16 mm), with multiple feeding arteries and several venous drainage structures to the umbilical vein and also a persistent ductus venosus. Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly. Heart US showed signs of volume overload with biventricular dilatation (predominantly right) and tricuspid regurgitation. Blood tests were normal except for high levels of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels ( > 5,000 ng/L). At day 7 of life, computed tomography angiogram was performed (Fig. 2), revealing an umbilical congenital AVM (36.6 × 16.6 × 22.3 mm) with feeding arteries originating from the external iliac, hypogastric, epigastric, and mammary arteries and a dilated umbilical vein (7 mm diameter) draining the cluster. Also, a patent ductus venosus was observed. No other malformations were found.

Fig. 1.

(A) Abdominal US and (B) Doppler US: 28 × 16 mm cluster, with a high density of vascularization, mixed arterial and venous. (C) Multiple feeding arteries coming from the external iliac, hypogastric, epigastric, and mammary arteries. (D) Enlarged umbilical vein, venous drainage of the lesion. US, ultrasound.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal CT shows the complex congenital umbilical AVM. (A) Umbilical drainage vein (arrow), (B and C) nidus is showed (asterisk), and (D) multiple efferent arteries coming from hypogastric and external iliac. AVM, arteriovenous malformation; CT, computed tomography.

She developed heart failure on day 12 of life and required mechanical ventilation and dopamine infusion.

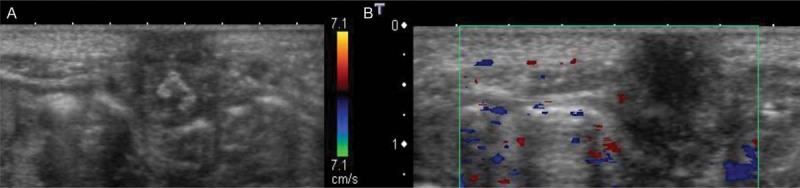

At 14 days of life, laparotomy was performed, and the umbilical vein and upper feeding arteries from subxiphoid up to supraumbilical level were ligated, no excision of the AVM was made. Analytical control after 24 hours of surgery showed a decrease in BNP levels (373 ng /L). Postoperative course was uneventful and the infant was discharged home on postoperative day 14 (28 days of life) being completely asymptomatic. Follow-up US (40 days after surgery) showed hyperechoic and thrombosed vascular structures, and thrombosis of umbilical vein and ductus venosus (Fig. 3). Arterial vessels coming from the hypogastric arteries and external iliac were thrombosed as well, with no flow inside. Eight months after discharge, no recurrence of the AVM has been discovered in our patient.

Fig. 3.

Postsurgical abdominal US (40 days after surgery): Hyperechoic and thrombosed vascular structures, and thrombosis of umbilical vein and ductus venosus. Arterial vessels coming from the hypogastric arteries and external iliac were thrombosed as well, with no flow inside. US, ultrasound.

Discussion

AVMs are rare in neonatal period, and they are mostly described in the brain and areas such as liver or extremities. Little is known about umbilical AVMs. Usually, umbilical arteries and vein are spontaneously closed during the first days of life. In some cases, like the one described herein, this physiological event is not possible because of the prenatal development of an abnormal vascularity. The patency of this weird vascularity can lead to different symptoms, as can be found in the literature. Less than 10 cases of congenital umbilical AVMs have been reported before, as can be seen in the resume at the end of this report (Table 1). Most of them involved only the umbilical arteries and vein. They have been mostly reported in males. Moreover, the importance of this case is that there is no previous communication of such a complex umbilical AVM with diverse feeding arteries originating from the chest. The etiology of these kind of malformations is not known yet, but they are no associated to AVMs in other areas or to other kind of malformations.

Table 1. Congenital umbilical AVMs reported until 2016.

| Report | Sex, GA | DOL | Principal sign | Size (mm) | Complementary tests | Surgical treatment | Postoperative course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gregorio, 2016, Spain | F, 34 wk | 4 | Abdominal murmur | 36.6 × 16.6 × 22.3 | Chest X-ray: cardiomegaly Echocardiography: volume overload, biventricular dilatation Angio-CT, Doppler US: multiple feeding arteries coming from external iliac, hypogastric, epigastric, and mammary arteries and a dilated umbilical vein |

Laparotomy; ligation of umbilical vein and upper feeding arteries from subxiphoid up to supraumbilical level | Uneventful |

| Gozar, 2014, Germany | F | 540 | Umbilical pulsatile murmur | 45 × 20 | Echocardiography: mildly dilated left cardiac chambers and a normal left ventricular function Angio-CT, Doppler US: umbilical arteries, emerging from the hypogastric artery, ascend to the umbilicus and after a tortuous trajectory flow into the umbilical vein |

Laparotomy; all vessels and the urachus were ligated and divided. Excision of the tumor | Uneventful |

| Boglione, 2013, Argentina | M | 20 | Wet umbilicus and hernia | 20 | Doppler US: a mass at the end of the umbilical cord harboring dilated blood vessels with turbulent blood flow which continued to the dilated umbilical vein and flowed into the liver. Angio-CT: umbilical arteries coming from both internal iliac arteries, into the mass directly at the end of the umbilical cord, and the dilated umbilical vein flowed out portal vein in the liver |

Ligation of umbilical arteries and umbilical vein and excision of the mass | Uneventful |

| Meyer, 2013, United States | M, 32 wk | Pulsatile umbilical stump | Data not shown | Echocardiography: normal global cardiac function Angio-CT, Doppler US: both umbilical arteries feeding a large cluster of vessels in the umbilical stump, with a widely patent umbilical vein draining the cluster |

Laparoscopy, ligation of feeding arteries and draining vein and excision of remaining malformation | Uneventful | |

| Shibata, 2009, Japan | M, 38 + 3 wk | 3 | Umbilical hemorrhage causing shock and cardiopulmonary arrest | Data not shown | Coagulopathy exams: normal Angio-CT: both umbilical arteries, which were patent from both internal iliac arteries, flowed into the mass directly under the umbilicus, and the enormously dilated umbilical vein flowed out from the mass to the portal vein |

Ligation of feeding arteries (two umbilical and one from left abdominal rectus) | No surgical complications. Psychomotor retardation has a consequence of cardiopulmonary arrest |

| Graham, 1989 | M, 35 wk | 2 | Heart failure | 15 | Chest X-ray: cardiomegaly Echocardiography: dilated cardiac chambers Cardiac catheterization: structurally normal with pulmonary hypertension Distal aortography: large right umbilical artery, complex AVM, and umbilical vein to patent ductus venosus to IVC |

Laparotomy, ligation of arteries and veins and en bloc excision of the entire AVM | Unremarkable |

| Murray, 1969, United States | M, term | 0 (birth) | Heart failure, dilated veins in the abdomen, close to the umbilicus | Data not shown | Chest X-ray: cardiomegaly Aortogram: early venous filling, dilatation of left inferior epigastric artery, and enormously dilated umbilical vein |

Ligation of three feeding arteries (two coming from inferior and superior epigastric arteries) and excision of umbilicus and surrounding vessels | Right bundle branch block, feeding intolerance, suspected surgical wound infection |

Abbreviations: Angio-CT, computed tomography angiogram; AVM, arteriovenous malformation; DOL, days of life; GA, gestational age; IVC, inferior vena cava.

Congenital umbilical AVMs can be asymptomatic, being diagnosed during the evaluation of an umbilical hernia or an abdominal murmur but some cases reported have been severe, leading to hemorrhagic shock1 or heart failure.2 3

In this overview, we have focused only in congenital malformations reported in English literature, excluding those related to previous procedures in the area of the umbilicus (e.g., catheterization of the vessels) and also those founded in the umbilical cord or stillbirths.

We have only found other two cases reported2 3 associated with high-output cardiac congestive failure, as the one we are presenting; one in 1969, starting with symptoms at the moment of birth who also recovered completely after the excision of the AVM but the authors did not describe in detail the preoperative findings and one in 1989, with 2 days of life, who was diagnosed after an aortogram and also recovered completely.

There is also one patient, reported by Shibata et al in 20091 diagnosed because of a hypovolemic shock related to a massive umbilical bleeding. This is the only report with long-term consequences (psychomotor retardation as an expression of the hypoxic-ischemic insult secondary to the shock), while in all the other cases, there are no major damages after the surgery, being all of them alive and asymptomatic at the moment of the report.

Regarding the surgical approach, in every case we have found, laparotomy has been performed,1 2 3 4 5 6 except for the one reported in 2013 by Meyer and Barsness,7 in which laparoscopy was selected. In all these cases, total excision of the malformation was performed after ligation of the feeding arteries. In our patient, due to the high complexity of the feeding arteries of the AVM, only ligation of these arteries was made, to reduce the surgical risks. To our knowledge, this is the first time that only ligation of the feeding arteries instead of complete excision is performed. This management was enough to get a progressive reduction of the size and spontaneous thrombosis of the malformation, as shown in the follow-up Doppler US (Fig. 3).

About the prognosis, the vast majority of the patients reported in the literature have an uncomplicated postoperative course1 2 3 4 5 6 7 and have been discharged without sequelae, with no recurrence of the mass reported. At this time (8 months after discharge), no recurrence of the AVM has been discovered in our patient.

Conclusion

Congenital umbilical AVMs are rare and only occasionally reported in the literature. They should be suspected in every abdominal murmur or thrill linked or not to any local or systemic symptomatology (bleeding, high-output cardiac failure…) that sometimes can be severe. Herein, we present the first case of congenital umbilical AVM with feeding arteries originating not only from abdominal but also from mammary arteries. Moreover, in complex AVMs, with high surgical risks, the only section of the feeding arteries can lead to the complete resolution of the AVM, as we show in this case report for the first time. Patients should be early diagnosed to achieve a complete resolution of the malformation with no long-term consequences.

Acknowledgment

No financial support received.

References

- 1.Shibata M, Kanehiro H, Shinkawa T. et al. A neonate with umbilical arteriovenous malformation showing hemorrhagic shock from massive umbilical hemorrhage. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(8):583–586. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham S M, Seashore J H, Markowitz R I, Hellenbrand W E. Congenital umbilical arteriovenous malformation: a rare cause of congestive heart failure in the newborn. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24(11):1144–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray D E, Meyerowitz B R, Hutter J J. Congenital arteriovenous fistula causing congestive heart failure in the newborn. JAMA. 1969;209(5):770–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gozar H, Gozar L, Badiu C C, Suciu H. Congenital umbilical arterio-venous malformation: a word of caution. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18(5):688–689. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivu019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcelo Boglione M, D. Alessandro P, Reusmann A, Rubio M, Lipsich J, Goldsmith G. Umbilical arteriovenous malformation in a healthy neonate with umbilical hernia. J Neonatal Surg. 2013;2(3):35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox T D, Winters W D, Holterman M J, Hatch E I, Skarin R M. Neonatal bowel ischemia attributable to an umbilical arteriovenous fistula: imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(4):940–942. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.4.7676996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer M, Barsness K A. Umbilical arteriovenous malformation: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29(8):851–853. doi: 10.1007/s00383-013-3297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]