Abstract

Media are one source for adolescent identity development and social identity gratifications. Nielsen viewing data across the 2014–2015 television season for adolescents ages 14–17 was used to examine racial and gender diversity in adolescent television exposure. Compared to U.S. Census data, mainstream shows underrepresent women, but the proportion of Black characters is roughly representative. Black adolescents watch more television than non-Black adolescents and, after taking this into account, shows popular with Black adolescents are more likely than shows popular with non-Black adolescents to exhibit racial diversity. In addition, shows popular with female adolescents are more likely than shows popular with males to exhibit gender diversity. These results support the idea that adolescents seek out media messages with characters that are members of their identity groups, possibly because the characters serve as tools for identity development and social identity gratifications.

Keywords: adolescents, media, identity, ethnicity, gender

Introduction

Adolescence is a turbulent period for identity processes, especially in middle adolescence, ages 14–17 (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006; Kroger, Martinussen, & Marcia, 2010; Moshman, 2005; Phinney, 1990). This is especially the case for members of minority racial and ethnic groups (Phinney, 2006), and for gender roles (Arnett, 1995). Identity development generally involves figuring out what it means to be a member of the relevant group (French et al., 2006). The process comprises trying to understand and question the expectations that society has surrounding one’s fundamental group memberships, which can include ethnicity, gender, sexuality, occupation, religion, and politics (Blasi & Glodis, 1995; Moshman, 2005). Theories of group identity development, coming from earlier theories of ego-based identity formation (i.e., Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1966; 1980) have suggested that most individuals go through a phase of identity questioning and searching before they find the relatively stable status of achieved or committed identity (Cross, 1995; Moshman, 2005; Phinney, 1990; Seaton, Scottham, & Sellers, 2006; Shelton & Sellers, 2000).

Identity status in Black adolescents tends to vary, with about half not currently searching or questioning their identity, a quarter actively searching for identity, and another quarter having an achieved ethnic identity at any given time (Phinney, 1990; Seaton et al., 2006). The likelihood of identity achievement and stability increases with age (Phinney, 1990). Previous research finds little difference in gender identity exploration processes or rates between men and women (Kroger et al., 2010). However, the identity search for females may include more aspects of sexuality and sexualization than it does for males (Marcia, 1980), and females and males report differences in the possible gender roles they hope to and fear to fulfill (Anthis, Dunkel, & Anderson, 2004). And, other work has found some personality differences between males and females in different stages of gender identity exploration (Cramer, 2000).

Importantly, strong identity formation is associated with positive outcomes for psychological well-being (Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind, & Vedder, 2001; Seaton et al., 2006; Shelton & Sellers, 2000). Achieved ethnic identity is associated with higher self-esteem in Black, Asian American, and Hispanic adolescents (Phinney & Chavira, 1992). Moreover, feeling contented with one’s gender identity was associated with higher self-worth compared to those less contented (Yunger, Carver, & Perry, 2004). Other work suggests that strong group identity can even provide a buffer against the harmful psychological effects of discrimination (Mossakowski, 2003; Romero, Edwards, Fryberg, & Orduña, 2014). Therefore, identity processes can be highly important for adolescent well-being, and it is potentially vital to understand what factors may play a role in those processes.

Media and Identity

Adolescents will often seek out relevant exemplars to help them understand what group membership means during the more uncertain stages of identity formation, and media messages are one possible exemplar source (Arnett, 1995). People make media choices for a variety of reasons including general mood management and adjustment (Knobloch, 2003; Oliver, 2003; Zillmann, 1988) and for specific purposes such as information, diversion, or social interaction (e.g., Uses and Gratifications; Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1973; Ruggiero, 2000). One possible reason for selecting media is put forward by the social identity gratifications perspective (Harwood, 1997), which grew out of a combination of social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and uses and gratifications theory (Katz et al., 1973). The social identity gratifications perspective suggests that people enjoy watching characters who are like them, and will be more likely to seek out content with those characters (Harwood, 1997).

The social identity gratifications perspective was originally conceptualized with age as the relevant social group (Harwood, 1997). However, the perspective has since been expanded to other identity realms, such as race, gender, and nationality. Importantly for the present study, previous research found that participants across the United States, Germany, and Britain rated television series with a protagonist matching their sex more highly than those with an opposite-sex protagonist (Trepte & Krämer, 2007). Another study found that African Americans with strong ethnic identity were actually more likely to avoid television when they expected it would have few and negative depictions of Black characters (Abrams & Giles, 2007).

Identity exploration and identity gratifications have also been proposed as a motivation for media use by adolescents specifically (Arnett, 1995; Coyne, Padilla-Walker, & Howard, 2013; Phinney, 2006). Media use differs from other sources of socialization (e.g., parents, school) in that the adolescents become active participants in their own identity construction through their explicit selection of media messages and media content (Arnett, 1995; Coyne et al., 2013). Media are an attractive identity information source because of the diversity in potential models within one’s group to choose from (Arnett, 1995). This is especially the case for adolescents with homogenous families and communities – the media provide information that is missing in their social lives. Adolescents may select media to have exposure to the many different ways that they could define themselves as a member of their relevant group (Arnett, 1995). Therefore, media provide adolescents an opportunity to safely (with some exceptions regarding stereotypes; see Phinney 2006) expose themselves to what other members of their identity group are doing.

The characters that adolescents watch are important not only for identity processes but also for models for behavior. According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986; 2001), enactment of modeled behavior is more likely to occur when the model experiences positive outcomes in response to the behavior, when the model is socially attractive, and when the model is perceived to be similar to the message receiver (Bandura, 2001). Previous work supporting the attractiveness and similarity portion has suggested that Black adolescents may be more influenced by Black media models, and that they may reject White characters as relevant models (Appiah, 2004). Similarly, Black adolescents have been found to more readily identify with and pay attention to Black characters, especially when the adolescents have strong ethnic identity (Appiah, 2001; Appiah 2002). This suggests that there is indeed a link between identity and adolescents’ selection of and reactions to media. Additionally, research has found more direct evidence that media models that represent different groups may have differential influences on behavior. For example, smoking initiation among Black youth is predicted by exposure to Black-oriented media but not mainstream media (Dal Cin, Stoolmiller, & Sargent, 2013). This suggests not only that media and identity are linked but also that the effect that media can have on adolescent behavior is a potentially important consequence of media selection and exposure.

The influence of group membership and identity in media selection is not limited to racial and ethnic categories, however. Other work has suggested that social cognitive processes and social identity gratification processes also occur with regards to the influence of gender roles (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). In addition to the finding that people rate shows more highly when the protagonist matches their sex (Trepe & Krämer, 2007), older work with children has found that young boys with a strong gender concept watch programs with a higher proportion of men (Luecke-Aleksa, Anderson, Collins, & Schmitt, 1995). In addition, adolescents are more likely to experience wishful identification, or a desire to emulate, with same-gender characters (Hoffner & Buchanan, 2005). Interestingly, unlike race differences in the amount of television exposure, where Black adolescents watch more television than Whites (Jordan et al., 2010), male and female viewers tend to watch television at similar rates. However, males and females watch different content types (Brown & Pardun, 2004; Eggermont, 2006; Van den Bulck & Van den Bergh, 2000). For example, male teens watch more youth action content, while female teens watch more soap operas and dramas (Eggermont, 2006). What remains to be seen, however, is whether male and female adolescents select content that is different in its representation of gender diversity.

The Current Study

The present study analyzes narrative television shows popular among various subgroups of adolescents for their patterns of racial and gender representation. Despite the increased popularity of other sources of media, recent reports of teen media use find that the more “traditional” media of television and music still dominate teen media diets (Rideout, 2015), and thus television remains a relevant source of possible identity gratifications and identity models for adolescents. Understanding the range of the portrayals of Black and female characters in popular adolescent television will provide not only information for what kinds of characters adolescents of different groups are drawn to, but also the types of behavioral models that adolescents are likely to be exposed to.

Previous research on Black characters in media suggest that television provides a fairly proportionate representation compared to the population of the United States (Tukachinsky, Mastro, & Yarchi, 2015). In contrast, a recent report on Hollywood diversity finds underrepresentation for ethnic minorities and women (Hunt, Ramon, & Price, 2014). However, both of these analyses used content popular with all age groups, not just with adolescents. It is important to get an idea of the level of diversity in television content that adolescents are exposed to in general, before breaking it down by identity groups. We, therefore, examine the question, are the proportions of Black and female characters in shows popular with adolescents equivalent to their proportion in the U.S. population?

Based in previous work on identity formation through media (Coyne et al., 2013; Arnett, 1995), the social identity gratifications perspective (Harwood, 1997), and on Black reactions to White and Black characters (Appiah, 2002; Appiah, 2004), we predict that television shows popular with Black adolescents will have more Black characters than shows popular with non-Black adolescents. Furthermore, Black adolescents tend to use more media than Non-Blacks (Jordan et al., 2010; Roberts & Foehr, 2004; Rideout 2010). In particular, Black adolescents on average view nearly twice as many hours of television per day than White adolescents and are more likely to have a television in their bedroom – an important factor in determining hours of television per day (Jordan et al., 2010). One possibility for this disparity in viewing is that Black adolescents are not just watching mainstream television, but also view “Black-oriented” media – content with predominantly Black casts that are targeted toward Black audiences (Dal Cin et al., 2013). Black-oriented media should fulfill identity gratifications more strongly than mainstream media, by offering a large number of Black characters and positive depictions of Black individuals. Previous work found that Black participants claimed to avoid television when they expected that there would not be enough depictions of Black characters or that what few depictions existed would be negative (Abrams & Giles, 2007). However, that work did not look at Black-oriented television, but instead television in general. It is possible that Black adolescents watch more television than non-Black adolescents because they are incorporating Black-oriented media into their television diet – perhaps because they can receive more identity gratifications from Black-oriented media than they do from mainstream media. Thus, we also predict that that more shows will be popular with Black adolescents compared to the non-Black adolescents, and we also predict that these shows will have a higher proportion of Black characters.

Gender should also be associated with selection of television shows with gender-congruent characters. Previous research on gender differences in television use finds that there is little overlap in shows that are popular with male and female adolescents (Brown & Pardun, 2004). One possibility is that females are watching more shows with female characters, while males are avoiding female characters (Eggermont, 2006), and research has found that television shows are rated more highly when the protagonists were of the same sex as the participant (Trepte & Krämer, 2007). We expect this same effect to be reflected in adolescent viewing patterns. Consequently, we predict that shows popular with female adolescents will include more female characters than shows popular with male adolescents.

Method and Measures

Data Source

Nielsen provided a report of television viewing data recorded between September 22, 2014 and June 28, 2015 on broadcast and cable channels. The statistics were based on live viewership plus seven days for recorded playback. The report could be examined as a composite of all ages, races, and genders or broken down into specific subgroups. The adolescent subgroup used for the present analysis is based on Nielsen data from a sample of adolescents in Nielsen households aged 14–17 years, with the sample ranging in size from 2,776 to 3,206 due to households and/or individuals entering and exiting the sample through the nine months of the season. Within the adolescent subgroup, we analyzed the viewing data from the following groups: all adolescents, Black adolescents, non-Black adolescents, male adolescents, and female adolescents. The age group of 14–17 years matches the time when previous work suggests identity exploration should be highest (French et al., 2006).

Ratings provided by Nielsen were used as the criteria for determining what shows are popular with each group. The ratings are the estimated average percentage of the viewing audience for the program, expressed as a percentage of the population selected. For example, a rating of 2.34 indicates that at any given time across the 2014–2015 season, on average, 2.34% of Americans with access to a television were watching that content. For context, the highest-rated event of the 2014–2015 season was Super Bowl XLIX, at a rating of 47.50, indicating that approximately 47.5% of all Americans with a television watched the Super Bowl last year (Breech, 2015). The Oscars©, another popular event, was rated 10.80 (Kissell, 2015). These high ratings are extremes, however; of all media titles in the data set prior to any filtering for analyses, less than seven percent of them (n=1,153) were rated at a 1.00 or higher across all ages.

Show Selection Criteria

Serial narrative content – television shows that remain consistent across the season in the cast of characters, settings, and themes – was selected for multiple reasons. On a theoretical and conceptual level, audience members relate to narratives differently than non-narratives. Identification with characters, transportation, and emotional reactions are all enhanced with narrative content as compared to non-narrative content (Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2013). In addition, reactions to characters such as parasocial relationships and wishful identification strengthen over time (Eyal & Cohen, 2006; Hoffner & Buchanan, 2005). Most importantly, narratives should be highly likely to offer the scripts needed for identity modeling (Arnett, 1995), meaning that this type of content should be the most influential on adolescent behavior. And on a practical basis, the coding of characters for each show was based in the listing of regular cast members for the 2014–2015 season. In shows where the characters change on an episode-to-episode basis, it would have been difficult to select a representative sample of characters.

Excluded genres include game shows and competitive reality shows (e.g., Dancing with the Stars), news, instruction, and documentaries (e.g., Good Morning America), award ceremonies, comedy and general variety (e.g., The Tonight Show), concert music and music videos, conversations and colloquies (e.g., The View), devotional, feature films, political (e.g., the State of the Union address), and sports anthology, sports commentary, and sports events. Content that was not in English was also excluded (e.g., Univision). Finally, miniseries were not included, nor were one-off specials (e.g., Spongebob: Truth or Square). Reality and sports content are immensely popular; however, they brought with them the previously-mentioned issues for coding and would not have offered the theoretical benefits that narratives provided. The removal of sports may be especially problematic due to its disproportionate popularity with male adolescents (the ratings for the ten highest-rated sports events for males were more than twice as high as those for the top ten for females). However, the inclusion of sports content would likely only serve to exacerbate any differences in gender selection, as the most popular sports content involves male-only sporting leagues such as the NFL, NBA, and NHL.

Defining the Popular Show Lists

Race and gender subgroups and their ratings were used to create lists of the 100 highest-rated (most popular) shows for each group, plus an extended list of shows popular with Black adolescents (see list selection criteria section below). Details about the shows that are popular by subgroup within each list can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of shows and their genres, organized by group within each list.

| Independent variables | Total # of Shows | Genre

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comedy | Drama | Child | Animated | ||

| All Adolescents Top 100 | 100 | 32 | 41 | 27 | 23 |

|

| |||||

| List 1 (Black and non-Black top 100) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Black Top 100 Unique | 55 | 21 | 11 | 23 | 37 |

| Common to non-Black and Black Top 100 | 45 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 15 |

| Non-Black Top 100 Unique | 55 | 17 | 35 | 3 | 2 |

|

| |||||

| List 2 (Black extended and non-Black top 100) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Black Extended Unique | 111 | 22 | 34 | 55 | 41 |

| Common to both Black Extended and non-Black | 44 | 11 | 30 | 3 | 2 |

| Non-Black Top 100 Unique | 45 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 15 |

|

| |||||

| List 3 (Black extended and Black top 100) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Black Extended | 155 | 33 | 64 | 58 | 43 |

| Black Top 100 | 100 | 33 | 26 | 41 | 52 |

|

| |||||

| List 4 (Male and Female top 100) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Male Top 100 Unique | 59 | 27 | 21 | 11 | 42 |

| Common to Male and Female Top 100 | 41 | 19 | 18 | 4 | 5 |

| Female Top 100 Unique | 59 | 4 | 21 | 34 | 7 |

| Total | 268 | 72 | 97 | 99 | 95 |

Defining the popular show list for Black adolescents

Black adolescents tend to use more media than Non-Black adolescents (Jordan et al., 2010; Roberts & Foehr, 2004; Rideout 2010), and this trend was reflected in the ratings for their Top 100 lists. The ratings on the Non-Black Top 100 list ranged from 2.59 to 0.62, whereas the Black Top 100 list started much higher at 19.10 (the #2 show was 5.74) and ended at 1.58. To account for this large difference in ratings, an extended list was created for the Black adolescents to match the lowest Non-Black rating (0.62). This extended list added another 155 shows to the Black list of top shows (255 shows total popular with Black adolescents). These additional shows suggests that Black adolescents are watching approximately 2.5 times the number of shows within the same ratings threshold as non-Black adolescents. In total, there were 655 shows across the five Top 100 (all adolescents, Non-Black, Black, male, female) and the Black extended list, and of those, 268 of them were distinct shows; the difference (387) can be accounted for by overlap between the lists.

Coding the Characters

Main characters were defined by the official network show websites whenever possible. When official information was not available the information was obtained from the credits in a recent episode of the show. If a recent episode was not available IMDB and Wikipedia were cross-checked to determine the characters. The race and gender presentation of 1,864 characters were coded based on morphological features. In cases where a category was unclear, for example if the racial background of an actor could not be determined visually, information was sought from official character descriptions and actor and actress websites and interviews. In some such instances, which were few in number, information was then ascertained that the actor was of partial African or African-American descent. These actors were coded as Black cast members because, although not necessarily reflected in their appearance, they may still be known to audience members as African-Americans. The cases of characters of partial Black descent were too few to separate out for meaningful analyses, but from a modeling perspective could still be important to include in the Black category. The category was coded as missing if the race and/or gender could not be ascertained. This was especially the case with certain styles of Japanese anime (e.g., kawaii, shōjo) where race and gender are often deliberately ambiguous.

Measures

The total number of main characters was recorded for each television show, as was the number of Black and female characters1. Racial and gender diversity were operationalized as proportions of Black and female characters, respectively, within each of the shows in the sample. To create the proportion measures, the number of characters that were coded as Black or female was divided by the total number of characters per show.

Statistical Analysis

The unit of analysis is a television show. The first analysis used one-sample t-tests to compare the diversity proportions in the 100 mainstream shows popular with all adolescents to the actual estimated population percentages in the United States. Because the diversity proportions in the television shows were square root transformed (after adding the constant of one; see results section below), the square root was also taken of the proportion in the population (again after adding the constant of one) to create the comparison value.

Analyses on the association between racial and gender diversity and show popularity were conducted using both ANOVA and t-tests. Show popularity was the independent variable and the amount of racial and gender diversity (i.e., the proportion of Black characters and the proportion of female characters) in its cast of characters were the dependent variables. Three ANOVAs and one independent samples t-test were used to test the prediction that show popularity with a particular group would be associated with the racial and gender diversity in those shows. Post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction were used to test for specific differences when the overall ANOVA F test was significant; details can be found in Table 2. The first ANOVA compares the racial diversity of shows that are popular with Blacks (i.e., on the top 100 for Black adolescents), shows that are popular with non-Blacks (i.e., on the top 100 for non-Black adolescents), and shows that are popular with both (i.e., appear in both the Black top 100 and non-Black top 100). The popularity of shows by group in this first ANOVA is referred to as “List 1 (Black and non-Black top 100)” in Tables 1 and 2, and was coded with three values: if a show was popular with non-Blacks only it was coded as (−1), if popular with Blacks only it was coded as (1), and if it was popular with both Blacks and non-Blacks it was coded as (0). For example, Empire was popular with both Black and non-Black adolescents (coded 0), but Black Dynamite was popular only with Black adolescents (coded 1) and Parks and Recreation was popular only with non-Black adolescents (coded −1). The second ANOVA compares the diversity of shows that are popular with non-Blacks (i.e., the top 100 for non-Black adolescents), shows that are popular with Blacks beyond the top 100 (i.e., the 155 shows on the extended Black list), and shows that are popular with both (i.e., appear in both the non-Black top 100 and extended Black list). The popularity of shows by group in this ANOVA is referred to as “List 2 (Black extended and non-Black top 100)” in Tables 1 and 2 and has three values: if a show was popular with non-Blacks only it was coded as (−1), if popular with Blacks only it was coded as (1), and if it was popular with both Blacks and non-Blacks it was coded as (0). An independent samples t-test was used to compare the diversity of shows that are in the top 100 for Black adolescents and shows that are in the extended Black list. The popularity of shows in the t-test is referred to as “List 3 (Black extended and Black top 100)” in Tables 1 and 2. The variable was coded with two values: if a show was in the top 100 shows for Blacks it was coded as (0) and if in the extended list of shows popular with Blacks it was coded as (1). Finally, the third ANOVA compares the gender diversity of shows that are popular with males (i.e., on the top 100 for male adolescents), shows that are popular with females (i.e., on the top 100 for female adolescents), and shows that are popular with both (i.e., appear in both the male top 100 and female top 100). The popularity of shows by group in this third ANOVA is referred to as “List 4 (Male and Female top 100)” in Tables 1 and 2. This variable was coded with three values: if a show was popular with males only it was coded as (−1), if popular with females only it was coded as (1), and if it was popular with both males and females it was coded as (0).

Table 2.

Means (with standard deviations in parentheses) and post hoc tests for differences in group proportion means (pre-transformation for ease of interpretation). Same subscripts within a row indicates no significant difference, different subscripts within a row indicate significant difference at p < .05. No subscripts indicates a non-significant F-test and thus no post hoc test. All results are based on ANOVA except for List 3, which is based on an independent samples t-test.

| Outcome Variable | List 1 (Black and non-Black top 100, n=155) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Black Unique | Common | Black Unique | |

| Proportion of Black Characters | 0.12(0.12) | 0.18(0.29) | 0.11(0.24) |

| List 2 (Black extended and non-Black top 100, n=200) | |||

| Black Ext. Unique | Common | Non-Black Unique | |

| Proportion of Black Characters | 0.38(0.40)a | 0.12(0.12)b | 0.18(0.29)b |

| List 3 (Black extended and Black top 100, n=255) | |||

| Black Ext. Unique | Common | Black 100 Unique | |

| Proportion of Black Characters | 0.29(0.36)a | -- | 0.14(0.27)b |

| List 4 (Male and Female top 100, n=159) | |||

| Male Unique | Common | Female Unique | |

| Proportion of Female Characters | 0.30(0.19)a | 0.38(0.13)b | 0.45(0.15)b |

Results

Summary information about the number of television shows in the tests of each list and their genres can be found in Table 1.

Proportions of Black Characters and Female Characters

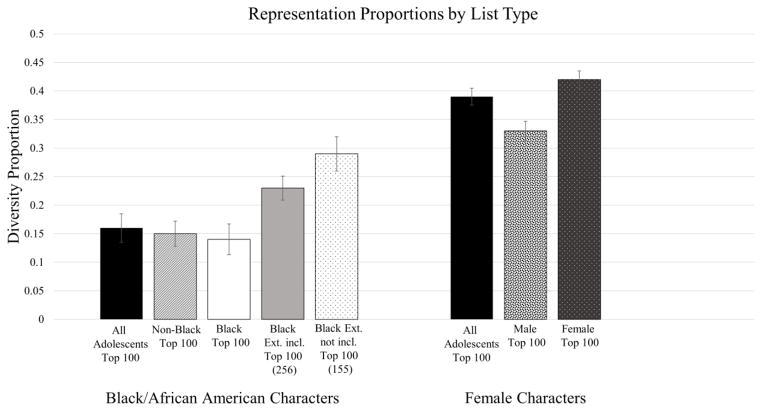

Central tendency information for these proportions can be found in Figure 1. As the figure shows, the list of shows with the highest proportion of Black characters was the Black extended list, and the list of shows with the highest proportion of female characters was the female top 100 list. Note, however, that the proportions in Figure 1 include overlap in shows across lists; this issue is corrected for in the list comparison analysis below. The proportions were all highly skewed except for female diversity, which, while not skewed, was kurtotic. The ladder of powers command in Stata determined that a square root transformation was best for all variables. Numbers less than one act differently when transformed than do numbers one and larger, so the constant of one was added to each before the transformation.

Figure 1.

(Dis)proportionate Representation

The list of the Top 100 most popular shows for all adolescents provides an opportunity to look at representation patterns in the television shows that are popular with adolescents in the mainstream. The United States Census Bureau (2014) estimates that 13.04% of the U.S. population is Black/African American and that 50.84% are female. Results of single-sample t-tests suggest that African Americans have fairly proportional representation in this mainstream list, with no significant difference between population estimates and the proportion of Black characters (M=0.16, SD=0.25), t(97)=0.99, p=.32. However, females are significantly underrepresented in popular mainstream television shows compared to their actual population (M=0.39, SD=0.15), t(99)=−7.45, p<.001.

Racial Diversity in Television Shows

Diversity in shows that are popular with Black adolescents was compared to diversity in shows that are popular with non-Black adolescents (with shows common to both groups treated as a distinct category). See Table 2 for results. There were no significant differences among the groups in List 1 in the proportions of characters that were Black or African American, F(2, 146)=1.05, p=.35, η2=.01.

The extended Black list was created because Black youth watch more television than other groups, and so we attempted to match the ratings on the list of the non-Black and Black groups. ANOVA analyses showed there was a significant difference by group popularity in racial diversity when comparing the shows popular with non-Black only, popular on the extended Black list only, and popular with both groups (List 2), F(2, 177)=10.65, p<.001, η2=.11. The shows that were unique to the extended Black list had significantly higher proportions of Black characters compared to the shows that were common to both lists or that were popular with non-Blacks only. A t-test comparing the List 3 groups indicated that shows on the extended Black list also had significantly higher proportions of Black characters compared to the shows on the Black top 100 list, t(225.18)=−3.72, p<.001, Cohen’s d=−0.48.

Gender Diversity

The final ANOVA compared shows popular with female adolescents to those popular with male adolescents. There were significant differences in the proportion of female characters between the groups, F(2, 156)=14.09, p<.001, η2=.15. Post hoc tests indicate that shows popular with males had a significantly smaller proportion of female characters than did shows popular with females and shows that were popular with both genders. There was no significant difference between the shows popular with females only and the shows popular with both genders in gender diversity.

Discussion

Adolescence is often a time of identity development, where individuals attempt to solidify what their group membership means and the ways to define themselves within that membership (French et al., 2006; Moshman, 2005; Phinney, 1990). One way that adolescents may explore and formalize their identities is by selecting media content with characters that match their racial and gender identity categories (Arnett, 1995; Coyne et al., 2013). Television viewing data for adolescents aged 14–17 was used to examine racial and gender diversity in the most popular programs for adolescents. Consistent with previous research (Tukachinsky et al., 2015), mainstream television shows were fairly proportionate to the population in representation of Black characters. However, female characters were underrepresented.

Racial diversity was comparable in shows popular with both Blacks and non-Blacks. The ratings data indicated that Black adolescents watch more television than non-Black adolescents (Jordan et al., 2010; Roberts & Foehr, 2004). When considering shows beyond mainstream popularity (i.e., Black extended), the proportion of Black characters is higher compared to other groups. Additionally, shows popular with female adolescents had more female characters than did shows popular with male adolescents. Thus, for both racial and gender identity groups, it seems that adolescents tend to gravitate toward content with more characters from their own groups. Racial diversity differences between the shows popular with Black and non-Black adolescents became apparent when taking into account the expanded media diet of Black adolescents. Thus, using a system that selects the “top 100” or other ranking without considering that television time and ratings vary by group may represent a flawed sampling approach, depending on the research questions of interest. Analyzing only mainstream shows may not be sufficient in investigations of differential content exposure and/or media effects (Dal Cin et al., 2013). Black youth are watching mainstream content, but importantly also are exposing themselves to content with more racial diversity. Additionally, diversity in these shows supports the premise that Black adolescents may be watching more television than non-Black adolescents in part to increase the number of Black characters in their media repertoire, above and beyond the Black characters presented in the mainstream. Of course, there are many other possible reasons for increased television use among Black adolescents. Researchers have often focused on demographic variables such as socioeconomic status (SES); however, previous research has found that the difference in viewing time remains even after SES is accounted for (Jordan et al., 2010). There is some evidence that parental education might play a role, but it is a non-linear and small difference that exists across racial groups (Rideout, 2015). However, variables such as SES and access to television in the home and bedroom do still predict viewing time differently for White and Black adolescents (Bickham et al., 2003; Jordan et al., 2010), and future research should look to how diversity exposure fits in as a potential supplemental predictor.

The finding that gender diversity varies when comparing the shows that are popular with female and male adolescents supports previous findings that males and females watch an equal amount of television but the content of that television is often very different (Brown & Pardun, 2004; Eggermont, 2006; Van den Bulck & Van den Bergh, 2000). Other work has suggested that male and female children may be more likely to select gender-congruent characters at a fairly young age (Luecke-Aleksa et al., 1995). The present work supports this previous research by offering evidence that adolescents watch content with more characters of their gender group, and suggests that perhaps this helps to explain the difference in the types of television watched by males and females.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The results of the present study provide support for the social identity gratifications perspective, which states that people like and seek out media characters that reflect their identity groups (Harwood, 1997). Previous work from this perspective found that participants prefer television content that contains people of their same age and gender (Harwood, 1997; Trepte & Krämer, 2007) and will avoid television content when they believe it will not depict their group members or will not depict them positively (Abrams & Giles, 2007). The present study adds to this work by offering evidence that adolescents are more likely to be exposed to television content that contains characters representing their identity groups – in this case, race and gender. In addition, the present work fits within models of identity formation that suggest adolescence as a time of identity searching and meaning-making (e.g., Cross, 1995; Moshman, 2005; Phinney, 1990; Seaton et al., 2006; Shelton & Sellers, 2000), and with previous work suggesting that media plays a large role in helping adolescents through these processes (Arnett, 1995; Coyne et al., 2013). The television shows in the present sample that were popular with different racial and gender groups of adolescents were more likely to contain higher proportions of characters belonging to the relevant identity groups. One possible explanation is that adolescents involved in identity searching, or even affirming their achieved or committed identities, were more likely to select media that allowed them access to relevant exemplars.

There are also implications for the present study grounded in social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001). Models for behavior are likely to be more impactful when they are socially attractive and more similar to the viewer (Bandura, 2001). This is borne out by other research finding that Black adolescents are indeed more influenced by Black media characters than by White media characters (e.g., Appiah, 2004; Dal Cin et al., 2013). Therefore, to the extent that adolescents are exposed to and/or watching media content with models that are similar to them, they are also observing models that theoretically will have stronger effects on their behaviors. This may have implications for health and risk disparities in both race and gender in that it is possible that media depictions of risk behaviors may contribute to differential outcomes.

Study Limitations and Future Research

It is possible that identity exploration and confirmation was not a reason for show selection for the adolescents in the sample. There has been much research on the reasons people select different media messages (e.g., Katz et al., 1973; Zillmann, 1988), and future work may wish to integrate identity exploration with the other motivations. Although the data support our hypotheses about using media for identity exploration and gratifications, we provide no individual level data. Two example motivations that could be associated with similar selection patterns but that do not necessarily have to do with identity processes are mere similarity and cultural resonance. The mere similarity perspective is rooted in work on the relationships between exposure, familiarity, and perceived similarity (e.g., Moreland & Zajonc, 1982). Basically, people like others who they perceive to be familiar and similar to themselves (Byrne, 1969; Moreland & Zajonc, 1982). The similarity in appearance between the viewer and the characters on television could increase the likelihood that the viewer likes the character and thus chooses his or her program to watch, without needing to involve the complications associated with identity.

Similarity in culture could also work in a comparable way. Cultural resonance in media is often discussed as part of framing research (e.g., Benford & Snow, 2000). However, some work has looked to the cultural resonance of characters and themes in entertainment media. For example, cultural resonance of archetypal characters and themes is associated with preference for entertainment messages (Faber & Mayer, 2009). It is possible that media with a large proportion of Black characters also contains archetypes and themes that resonate with Black adolescents. It is currently unclear whether Black cultural themes are a necessary condition to consider a media event to be “Black-oriented”, or whether simply having a predominantly Black cast is sufficient. Some previous research defines Black-oriented as being based in the casting of a predominantly Black cast only (e.g., Schooler, Ward, Merriwether, & Caruthers, 2004), while others say that the content must also contain Black cultural themes (e.g., Dal Cin et al., 2013). Future research should attempt to parse out when adolescents’ motivations to seek out content with characters from their identity group is due to identity formation and gratifications, mere similarity, cultural resonance, or a combination of the three (the most likely answer).

Of course, adolescent television use does not occur in a vacuum. Nielsen asks individuals to sign into their profile by pressing a button on a remote control when they begin watching and to sign out when they stop watching (National Reference Supplement NRS-REF-9.0, 2015). Based on this, we can be fairly confident that the adolescents in the sample were indeed watching the content. However, there was no information available on any potential co-viewing of content with other individuals. This means that co-viewing could have occurred in many instances with parents, siblings, or friends, and in some of those cases, those individuals could have selected the content and not the teen. Previous work on co-viewing between parents and their children has found that co-viewing is usually in addition to teens’ usual screen time, and does not replace the time adolescents spend viewing television alone (Bleakley, Jordan, & Hennessy, 2013). This suggests that, although in some instances the content viewed by the adolescents in the present sample may have been co-viewed and possibly selected by others, there is likely to remain a large amount of time that adolescents are choosing and watching television on their own. In addition, media have always been considered to be just one of many important sources of socialization, including parents and peers (Arnett, 1995; Coyne et al., 2013). If parents and peers are partially to blame for selecting group-consistent television content, then those sources of socialization are likely mutually reinforcing with the adolescents’ own media selection – the adolescent is not only likely seeking identity-consistent models but also is encouraged by other sources of socialization to select those models.

Finally, the television viewing data included in this analysis did not include shows in the 2014–15 television season that began airing after June 28, 2015. This does capture most of the traditional 2014–2015 season, as the majority of major shows air from September to May. Shows that aired at least two episodes before June 28, 2015 were included, meaning most summer-only shows were captured. But, a handful may have been missed.

Conclusion

Media may offer adolescents a chance to explore their racial and gender identities and the meaning of their group memberships by selecting content with characters that match their own identity groups. The present work uses adolescent viewing data to investigate patterns of diversity in shows popular with adolescents. Black adolescents report higher ratings than non-Black adolescents overall, watching approximately 2.5 times the number of shows within the same ratings threshold as non-Black adolescents. In line with the hypothesis that adolescents may select media content consistent with their relevant identity groups, within these “extra” shows is a higher likelihood that a show will contain a larger proportion of Black characters as compared to shows also watched by non-Black adolescents. Furthermore, shows popular with a female audience had a larger proportion of female characters. These results indicate not only that Black adolescents do gravitate toward shows with many Black characters and female adolescents gravitate toward shows with many female characters, but also that research on media effects on Black adolescents should include Black-oriented media in addition to mainstream content (Dal Cin et al., 2013). Identity formation is an important part of adolescent development, and the present results suggest one mechanism for how media may play a role in the identity formation process.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (Grant Number 1R21HD079615).

Biographies

Morgan E. Ellithorpe is the Martin Fishbein Postdoctoral Fellow in the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. Her areas of research include media psychology and media effects in the areas of health and risk, stereotyping and prejudice, and moral behavior.

Dr. Amy Bleakley is a senior research scientist in the Health Communication group at the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research focuses on investigating media effects on health risk behaviors and using theory to create evidence-based health interventions. While most of her research focuses on youth, specific content areas include sexual behavior, tobacco use, STD/HIV prevention, and obesity-related behaviors, as well as media use and exposure.

Footnotes

During coding non-human characters (e.g., Aqua Teen Hungerforce) emerged as a substantial proportion of the sample, and were also coded for exploratory analysis. Shows popular with Black and male youth had significantly more non-human characters than shows popular with non-Blacks and females, respectively. However, it is unclear why male and Black adolescents should be more likely to select media content with non-human characters, and future research should consider the possible motivations.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD.

Author Contributions: ME conceived of the study, ran most statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft. AB participated in data analysis decision-making, ran some statistical analyses, and helped with subsequent drafts of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest:

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Morgan E. Ellithorpe, Email: mellithorpe@asc.upenn.edu, Postdoctoral Fellow, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, 3901 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, (215) 573-5216

Amy Bleakley, Email: ableakley@asc.upenn.edu, Senior Research Scientist, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, 3901 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, (215) 573-1961.

References

- Abrams JR, Giles H. Ethnic identity gratifications selection and avoidance by African Americans: A group vitality and social identity gratifications perspective. Media Psychology. 2007;9:115–134. doi: 10.1080/15213260709336805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anthis K, Dunkel CS, Anderson B. Gender and identity status differences in late adolescents’ possible selves. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appiah O. Ethnic identification on adolescents’ evaluations of advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research. 2001;41:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Appiah O. Black and White viewers’ perception and recall of occupational characters on television. Journal of Communication. 2002;52:776–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02573.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appiah O. Effects of ethnic identification on web browsers’ attitudes toward and navigational patterns on race-targeted sites. Communication Research. 2004;31:312–337. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescents’ uses of media for self-socialization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:519–533. doi: 10.1177/0093650203261515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology. 2001;3:265–299. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benford RD, Snow DA. Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:611–639. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611. [Google Scholar]

- Bickham DS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, Lee JH, Caplovitz AG, Wright JC. Predictors of children’s electronic media use: An examination of three ethnic groups. Media Psychology. 2003;5:107–137. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0502_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi A, Glodis K. The development of identity: A critical analysis from the perspective of the self as subject. Developmental Review. 1995;15:404–433. doi: 10.1006/drev.1995.1017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Jordan AB, Hennessy M. The relationship between parents’ and children’s television viewing. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e364–e371. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breech J. Super Bowl 49 watched by 114.4M, sets U.S. TV viewership record. CBSsports.com. 2015 Retrieved on September 29, 2015 from http://www.cbssports.com/nfl/eye-on-football/25019076/super-bowl-49-watched-by-1144m-sets-us-tv-viewership-record.

- Brown JD, Pardun CJ. Little in common: Racial and gender differences in adolescents’ television diets. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2004;48:266–278. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4802_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey K, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review. 1999;106:676–713. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne D. Attitudes and attraction. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 4. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 36–89. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne SM, Padilla-Walker LM, Howard E. Emerging in a digital world: A decade review of media use, effects, and gratifications in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood. 2013;1:125–137. doi: 10.1177/2167696813479782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE. The psychology of nigrescence: Revising the Cross model. In: Ponterro JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, Alexander CM, editors. Handbook of multicultural counseling. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 1995. pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Stoolmiller M, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in movies and smoking initiation among black youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont S. Developmental changes in adolescents’ television viewing habits:Longitudinal trajectories in a three-wave panel study. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2006;50:742–761. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem5004_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eyal K, Cohen J. When good Friends say goodbye: A parasocial breakup study. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2006;50:502–523. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem5003_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faber MA, Mayer JD. Resonance to archetypes in media: There’s some accounting for taste. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43:307–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL. The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood J. Viewing age: Lifespan identity and television viewing choices. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 1997;41:203–213. doi: 10.1080/08838159709364401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffner C, Buchanan M. Young adults’ wishful identification with television characters: The role of perceived similarity and character attributes. Media Psychology. 2005;7:325–351. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0704_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt D, Ramon A, Price Z. 2014 Hollywood diversity report: Making sense of the disconnect. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.bunchecenter.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2014-Hollywood-Diversity-Report-2-12-14.pdf.

- Jordan A, Bleakley A, Manganello J, Hennessy M, Steven R, Fishbein M. The role of television access in the viewing time of US adolescents. Journal of Children and Media. 2010;4:355–370. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2010.510004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E, Blumler JG, Gurevitch M. Uses and gratifications research. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1973;37:509–523. doi: 10.1086/268109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kissell R. Update: Oscar ratings down 16%, lowest in six years. Variety. 2015 Retrieved on September 29, 2015 from http://variety.com/2015/tv/ratings/oscar-ratings-abc-telecast-down-10-in-overnights-to-four-year-low-1201439543/

- Knobloch S. Mood adjustment via mass communication. Journal of Communication. 2003;53:233–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb02588.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J, Martinussen M, Marcia JE. Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:683–698. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecke-Aleksa D, Anderson DR, Collins PA, Schmitt KL. Gender constancy and television viewing. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:773–780. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.5.773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland RL, Zajonc RB. Exposure effects in person perception: Familiarity, similarity, and attraction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1982;18:395–415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(82)90062-2. [Google Scholar]

- Moshman D. Adolescent psychological development: Rationality, morality, and identity. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:318–331. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1519782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST, Frank LB, Chatterjee JS, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Narrative versus non-narrative: The role of identification, transportation, and emotion in reducing health disparities. Journal of Communication. 2013;63:116–137. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Reference Supplement NRS-REF-9.0. The Nielsen Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MB. Mood management and selective exposure. In: Jennings B, Roskos-Ewoldsen D, Cantor J, editors. Communication and emotion: Essays in honor of Dolf Zillmann. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: A review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity exploration in emerging adulthood. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Chavira V. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: An exploratory longitudinal study. Journal of adolescence. 1992;15:271–281. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(92)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Horenczyk G, Liebkind K, Vedder P. Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:493–510. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V. The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens.

- Roberts DF, Foehr UG. Kids and media in America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Edwards LM, Fryberg SA, Orduña M. Resilience to discrimination stress across ethnic identity stages of development. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2014;44:1–11. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero T. Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Communication & Society. 2000;3:3–37. doi: 10.1207/S15327825MCS0301_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Schottham KM, Sellers RM. The status model of racial identity development in African American adolescents: Evidence of structure, trajectories, and well-being. Child Development. 2006;77:1416–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00944.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D, Ward LM, Merriwether A, Caruthers A. Who’s that girl: Television’s role in the body image development of young White and Black women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00121.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Sellers RM. Situational stability and variability in African American racial identity. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:27–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0095798400026001002. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin W, Worchel S, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA, USA: Brooks/Cole; 1979. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Trepte S, Krämer N. Hamburger Forschungsbericht zur Sozialpsychologie Nr. 78. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Arbeitsbereich Sozialpsychologie; 2007. Expanding social identity theory for research in media effects: Two international studies and a theoretical model. Retrieved from http://psydok.sulb.uni-saarland.de/volltexte/2008/2341/pdf/HAFOS_78.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tukachinsky R, Mastro D, Yarchi M. Documenting Portrayals of Race/Ethnicity on Primetime Television over a 20-Year Span and Their Association with National-Level Racial/Ethnic Attitudes. Journal of Social Issues. 2015;71:17–38. doi: 10.1111/josi.12094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States, states, and counties: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014. [Accessed on August 19, 2015];2014 from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

- Van den Bulck J, Van den Bergh B. The influence of perceived parental guidance patterns on children’s media use: Gender differences and media displacement. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2000;44:329–348. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4403_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yunger JL, Carver PR, Perry DG. Does gender identity influence children’s psychological well-being? Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:572–582. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zillmann D. Mood management through communication choices. American Behavioral Scientist. 1988;31:327–340. doi: 10.1177/000276488031003005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]