Abstract

Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) may promote wellbeing for sexual minority youth (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, or questioning youth) and heterosexual youth. We considered this potential benefit of GSAs in the current study by examining whether three GSA functions – support/socializing, information/resource provision, and advocacy – contributed to sense of agency among GSA members while controlling for two major covariates, family support and the broader school LGBT climate. The sample included 295 youth in 33 Massachusetts GSAs (69% LGBQ, 68% cisgender female, 68% white; Mage = 16.06 years). Based on multilevel models, as hypothesized, youth who received more support/socializing, information/resources, and did more advocacy in their GSA reported greater agency. Support/socializing and advocacy distinctly contributed to agency even while accounting for the contribution of family support and positive LGBT school climate. Further, advocacy was associated with agency for sexual minority youth but not heterosexual youth. Greater organizational structure enhanced the association between support/socializing and agency; it also enhanced the association between advocacy and agency for sexual minority youth. These findings begin to provide empirical support for specific functions of GSAs that could promote wellbeing and suggest conditions under which their effects may be enhanced.

Keywords: Gay-Straight Alliance, Agency, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, youth programs, Social support, Advocacy, Resilience

Introduction

More studies are focusing on resilience among sexual and gender minority youth (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender youth; LGBT) and sources that promote their positive development (Russell, 2005; Saewyc, 2011). One source that has come to receive attention has been Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs). GSAs are school-based groups that provide a multi-purpose setting for LGBT and heterosexual cisgender youth to socialize and receive support, to gain access to resources and learn about LGBT issues, and to engage in advocacy efforts to raise awareness and address issues of inequality in the school or broader community (Griffin, Lee, Waugh, & Beyer, 2004). Non-experimental comparisons show that youth in schools with GSAs report lower physical, psychological, and behavioral health concerns than youth in schools without GSAs (Davis, Stafford, & Pullig, 2014; Heck, Flentje, & Cochran, 2011; Poteat, Sinclair, DiGiovanni, Koenig, & Russell, 2013; Toomey & Russell, 2013; Walls, Kane, & Wisneski, 2010). Building on these findings related to GSA presence, in this study we focus directly on GSA members to identify GSA-related factors that account for variability among members in their levels of wellbeing.

There are several reasons to focus more closely on GSAs and their role in promoting their members’ wellbeing. There is strong evidence in the developmental literature of the value of youth programs (Catalano, Berglund, Ryan, Lonczak, & Hawkins, 2004; Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Mahoney, Harris, & Eccles, 2006), but there has been little attention to programs that focus explicitly on issues of sexual orientation. There are over four thousand GSAs across the U.S., with their numbers continuing to rise (GLSEN, n.d.; GSA Network, n.d.). GSAs are located in nearly all states, although students across a number of schools still face barriers when attempting to form or join a GSA (GSA Network, n.d.; Mayo, 2008). In contrast to other equally prominent youth programs (e.g., 4-H, Big Brothers Big Sisters, Boys and Girls Club; Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Grossman & Tierney, 1998), GSAs have received less attention and could benefit from additional empirically-supported guidance for how to maximize the utility of their services. The findings that point to the potential benefits of GSA presence are encouraging; yet, more specific attention to how GSAs promote wellbeing is needed.

We examine how involvement in several GSA functions may relate to youth wellbeing in the form of agency, defined as belief in one’s capacity to initiate and sustain actions (Snyder et al., 1996). Agency is a major youth asset that programs seek to promote (Larson, 2006; Larson & Angus, 2011). Also, agency is important in relation to other developmental tasks and outcomes during adolescence such as identity development and civic engagement (Koepke & Denissen, 2012; Larson, 2000). Further, GSAs are youth-led with adult support (Griffin et al., 2004); this setup provides a basis on which many opportunities should be available to promote agency. As such, among GSA members, we consider whether greater involvement in three major domains of GSA functions – receiving support and socializing opportunities, information and resources, and advocacy – is connected to greater agency while controlling for other major contributors and while testing conditions under which these associations may be stronger.

Functions of GSAs that Could Foster Youth Agency

For the most part, studies of GSAs have essentially treated them as monolithic entities (i.e., they have not considered specific facets of GSAs, only treating them as groups that either do or do not exist within a school) and have treated GSA members as a homogenous group when comparing them to non-members. Consequently, studies have not identified specific functions or characteristics of GSAs that actually contribute to the benefits of being involved in them, nor have they considered variability in youth’s experiences in them. As noted, GSAs seek to promote youth development through several major functions such as providing support and socializing opportunities, providing information and resources, and advocacy. Studies have yet to test whether variability in youth’s involvement in each of these domains relates to wellbeing.

Youth who receive more support and socializing opportunities from their GSA may report greater agency. One aim of GSAs and many youth programs is to provide a setting safe for socializing and for receiving emotional and social support (Dawes & Larson, 2011; Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Griffin et al., 2004). In fact, this was the main aim of GSAs when they first originated (Griffin et al., 2004). Peers become a major source of support during adolescence (Berndt, 2002), and this is often gained through interactions in extracurricular settings (Feldman & Matjasko, 2005). Indeed, engaging with prosocial peers in extracurricular settings partly accounts for the association between membership in these groups and youth wellbeing (Fredricks & Eccles, 2005). For many GSA members, both heterosexual and sexual minority, this setting may be one of few places in which they can make friends, interact without fear of victimization, or receive validation. This support may foster youth’s confidence and enable them to work toward their goals. Emerging findings from a smaller pilot study indicate that youth who perceive their GSAs to be more supportive also report greater mastery, self-esteem, and sense of purpose (Poteat et al., 2015); we expect that this association extends to agency.

There are several reasons why youth who receive more information and resources through their GSAs may report higher levels of agency. The standard school curriculum rarely includes LGBT individuals and issues (Russell, Kosciw, Horn, & Saewyc, 2010). Thus, a number of youth may feel hindered by having less information about unique stressors that they face or they may perceive services and service providers as unsupportive, discriminatory, or ill-equipped to meet their needs. GSAs may fill a vital role by offering referrals to other LGBT-affirming agencies, providing training around LGBT topics, and offering resources related to healthy coping strategies that speak to members’ unique needs (e.g., coping with parental rejection). As such, although the resource provision role of GSAs has been less emphasized than their support and advocacy roles, it may still relate to youth’s agency.

Many GSAs, as well as other programs serving marginalized youth populations, now incorporate advocacy as a part of their mission (Fields & Russell, 2005; Ginwright, 2007; Inkelas, 2004; Taines, 2012). For example, some GSAs provide opportunities for youth to plan and hold events that speak out against homophobic bullying and discrimination (e.g., ThinkB4YouSpeak or Transgender Day of Remembrance; GLSEN, n.d.; GSA Network, n.d.), to petition against discriminatory policies (e.g., policies prohibiting taking same-sex partners to prom), or to raise general LGBT awareness or educate peers about LGBT issues (e.g., developing inclusive curricula for health classes). The process of planning and implementing these activities provides opportunities for many youth to take on leadership roles, express themselves, and affect school or community programming or policy, all of which could build agency by raising their confidence to initiate and sustain actions to achieve goals. Indeed, youth have reported feeling empowered by their advocacy work in GSAs (Russell, Muraco, Subramaniam, & Laub, 2009) and in other school-based programs (Taines, 2012).

Across the major dimensions of support and socializing, information and resources, and advocacy in GSAs, we consider whether these functions relate to greater agency for some youth more than others. As reflected in their name and mission, GSAs aim to be inclusive of sexual minority and heterosexual ally youth. Yet, studies have not considered whether youth from both groups benefit equally from their involvement in each of these functions. Findings that show youth in schools with GSAs report greater wellbeing suggest that the benefits of GSAs apply to both sexual minority and heterosexual youth (Davis et al., 2014; Heck et al., 2011; Poteat et al., 2013; Walls et al., 2010). Nevertheless, these findings give little indication of variation in experiences of actual members and do not capture whether specific functions of GSAs are equally related to wellbeing for both groups. We address this issue directly in the current study.

The Moderating Role of GSA Organizational Structure

Although the youth-program literature has shown that youth who are more engaged within a program benefit more from their membership (Dawes & Larson, 2011; Pearce & Larson, 2006), certain factors could magnify or attenuate this link. In particular, youth program models underscore the need for adequate organizational structure (Catalano et al., 2004; Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Wood, Larson, & Brown, 2009). Of note, some youth have expressed aversion to joining their school’s GSA due to its perceived disorganization (Heck, Lindquist, Stewart, Brennan, & Cochran, 2013). Again, GSAs should not be considered standardized; they do vary in how they operate (Poteat et al., 2015). Thus, we consider organizational structure as a key facet along which GSAs could vary and that could account for why youth in some GSAs might benefit more than youth in other GSAs from receiving more support and socializing, information and resources, and from doing more advocacy. We consider organizational structure to be indicated by features such as agenda setting, leadership and facilitation (e.g., having a designated person who facilitates meetings), and deliberate continuity in addressing issues (e.g., conducting check-ins at the beginning of meetings and follow-up on discussions from prior meetings). Some of these features have been listed as helpful for running GSA meetings (GLSEN, n.d.), but they have not been examined empirically in relation to potential benefits for GSA members.

Greater organizational structure in the GSA may not itself be directly associated with greater agency among youth members. Instead, structure may maximize the potential for GSA functions actually intended to promote agency (i.e., support and socializing, information and resources, or advocacy) to be effective. Because GSAs attempt to provide a range of simultaneous services to youth, adequate amounts of organizational structure may be especially important in order to balance and coordinate the provision of these services and to ensure their consistency and quality. In this case, the GSA’s organizational structure may act as a moderator: for youth in GSAs with greater organizational structure, their own receipt of support and socializing, information and resources, and advocacy may be more strongly associated with a greater sense of agency than for youth who are in GSAs with less organizational structure.

Accounting for other Relevant Covariates

GSAs are one setting among many that have the potential to promote youth development. In addition to examining whether each of the three aforementioned functions of GSAs contribute to youth agency, we test for their distinct contributions over and above effects attributable to two other relevant sources. First, it is well established that family support contributes substantially to healthy youth development (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Thus, we consider whether GSA functions are associated with youth’s sense of agency over and above youth’s perceived level of family support. Second, GSAs are based in schools that themselves vary in their support for LGBT individuals. Although youth in schools with GSAs report safer climates than youth in schools without GSAs (Heck et al., 2011), some schools with GSAs are more supportive than others (Watson, Varjas, Meyers, & Graybill, 2010). As with family support, school support can build youth assets (Greenberg et al., 2003). Thus, to provide a more refined sense of the extent to which GSA-based experiences uniquely relate to agency, we further control for youth’s perceptions of the overall LGBT climate of their school.

Current Study and Hypotheses

GSAs are uniquely positioned to promote a sense of agency among youth members. We tested whether three GSA functions – support and socializing, information and resources, and advocacy – each uniquely contributed to sense of agency among members while controlling for two major covariates, family support and the broader school LGBT climate. Further, we considered whether each of these functions was related to greater agency equally for sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Finally, we considered whether the GSA’s level of organizational structure moderated the extent to which youth’s receipt of support and socializing, information and resources, and engagement in advocacy was connected to their sense of agency.

We tested several hypotheses using multilevel modeling of youth (Level 1) within their GSAs (Level 2). At the individual level, we hypothesized that levels of support and socializing, information and resources, and advocacy would each distinctly contribute to youth’s sense of agency, even when controlling for youth’s perceptions of their own family’s support and school LGBT climate. We based this hypothesis on extant literature that highlights social support as an important provision of youth programs, that LGBT issues are often absent in education curricula, and from youth reports that doing advocacy in their GSA led them to feel empowered (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Russell et al., 2009, 2010). We also controlled for grade level, as youth in higher grade levels may already feel more empowered based on their more dominant position in the school hierarchy. For exploratory purposes, we tested whether each of these GSA functions was associated with agency equally for sexual minority and heterosexual youth. At the group level, we further controlled for the collective perceptions of organizational structure in the GSA among members in the same GSA and the collective perceptions of school LGBT climate among members in the same GSA. Finally, we hypothesized that the GSA’s organizational structure would moderate the associations between GSA functions and youth’s agency. Specifically, we hypothesized that these functions would be more strongly associated with agency for youth in GSAs with greater organizational structure. We based this hypothesis on youth program models that emphasize the need for adequate structure in order for such programs to be effective (Catalano et al., 2004; Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Wood et al., 2009).

Method

Participants and Data Source

We conducted secondary analyses of the 2014 Massachusetts GSA Network survey. The Network is a joint program of the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth and the Massachusetts Safe Schools Program for LGBTQ Students. It gathers data as part of needs assessments, program evaluations, and to identify best practices for GSAs. The data from the 2014 survey were collected at regional conferences throughout Massachusetts and through postings to GSA advisors on the Network’s GSA listserv. All known GSAs in the state of Massachusetts were invited to send current GSA members to conferences affiliated with their regional location. At the regional conferences, surveys were given during a period at the start of the conference. Also, GSA advisors requested surveys through the listserv, which they then made available to and collected from youth. In both cases, youth voluntarily completed the anonymous survey if their advisor granted adult consent. The Network uses adult consent over parental consent because there are potential risks of inadvertently outing LGBT youth to parents. This is a common practice in LGBT youth research to protect youth’s safety and confidentiality (Mustanski, 2011). Youth were told that their responses would be anonymous and that data are used for program evaluation and potentially for research purposes to produce reports or articles. Youth who did not want to complete the survey at the conferences were able to do other activities. Youth who did not want to complete the survey available from their GSA advisor could elect not to ask for a survey. We secured IRB approval for our secondary data analyses.

There were 308 youth in 42 GSAs who completed the survey. Because our study focused on individual and group factors associated with youth agency and our analyses situated youth within their GSAs, we only included participants who were in GSAs with three or more members represented in order to avoid problems with no variability in scores within GSAs. Our final sample included 295 youth from 33 GSAs ranging in age from 13 to 20 years (Mage = 16.06, SD =1.13). The demographic representation of our sample is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Representation of Youth Participants

| Demographic Factor | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Grade Level | |

| Grade 8 | 4 (1.4) |

| Grade 9 | 47 (15.9) |

| Grade 10 | 90 (30.5) |

| Grade 11 | 95 (32.2) |

| Grade 12 | 55 (18.6) |

| Not reported | 4 (1.4) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 87 (29.5) |

| Lesbian or gay | 73 (24.8) |

| Bisexual | 59 (20.0) |

| Questioning | 18 (6.1) |

| Other self-reported sexual orientations | 55 (18.6) |

| Not reported | 3 (1.0) |

| Gender | |

| Cisgender female | 200 (67.8) |

| Cisgender male | 66 (22.4) |

| Gender-queer | 9 (3.0) |

| Transgender | 11 (3.7) |

| Other self-reported gender identities | 7 (2.4) |

| Not reported | 2 (0.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 201 (68.1) |

| Biracial/multiracial | 32 (10.9) |

| Latino/a | 18 (6.1) |

| Asian/Asian American | 16 (5.4) |

| Black or African American | 16 (5.4) |

| Native American | 4 (1.4) |

| Other self-reported racial/ethnic identities | 5 (1.7) |

| Not reported | 3 (1.0) |

Note. Total sample size: n = 295.

Measures

Demographics

Youth reported their sexual orientation, gender, and race or ethnicity. Sexual orientation response options were: lesbian or gay, bisexual, questioning, heterosexual, or other write-in responses. Responses were dichotomized as heterosexual or sexual minority because of the limited number of youth in each specific sexual minority group (write-in responses represented non-heterosexual identities such as pansexual or queer). Gender response options were: male, female, transgender (male to female), transgender (female to male), gender-queer, or other write-in responses. Because of the limited number of youth in the specific transgender, gender-queer, and other write-in responses, we considered them together in a trans/gender-queer group for analyses (write-in responses reflected gender-queer identities such as gender fluid or non-binary/pangender). Race or ethnicity response options were: Asian/Asian American, Black or African American, Latino/a, Native American, White (non-Hispanic), bi/multiracial, or other write-in responses. Responses were dichotomized as white or racial/ethnic minority because of the limited number of youth in each specific racial or ethnic minority group. Youth also reported their current grade level.

Perceived family support

Youth reported their perceived level of family support across four items from the Multidimensional Measure of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988): (a) My family really tries to help me; (b) I get the emotional help and support I need from my family; (c) I can talk about my problems with my family; and, (d) My family is willing to help me make decisions. Response options ranged from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). Higher average scale scores represent greater perceived family support. Coefficient alpha reliability was a = .93.

Support/socializing, information/resources, and advocacy

Youth responded to a 17-item index developed to assess the extent to which they received various provisions or resources or did a range of activities most commonly aligned with the mission of GSAs to provide support and socializing opportunities, access to information and resources, and advocacy opportunities. Youth were asked to report the extent to which they personally felt they got each thing from their GSA. Response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). All items are presented in Table 2. An exploratory factor analysis with principal axis factor extraction and varimax rotation indicated a three-factor structure to be the best representation based on eigenvalues over 1.00 and total percentage of variance accounted for by the factors (57.62%). As shown in Table 2, items had factor loadings that were high on their primary factor with low cross-loadings on the other factors. This yielded a 7-item support/socializing scale (e.g., “Validation and reassurance”), a 7-item advocacy scale (e.g., “Organize school events to raise awareness of LGBT issues”), and a 3-item information/resource scale (e.g., “Learn ways to deal with stress”). Higher average scale scores on each factor represent greater support or socializing received from the GSA, greater information and resources received from the GSA, and greater advocacy done in the GSA. Coefficient alpha reliability estimates were a = .90 (support/socializing), a = .87 (advocacy), and a = .84 (information/resources).

Table 2.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of GSA Support/Socializing, Advocacy, and Information/Resources

| Item | Support/ Socializing | Advocacy | Information/ Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| A place of safety | .79 | .21 | .18 |

| Emotional support | .79 | .17 | .22 |

| Validation and reassurance | .78 | .19 | .23 |

| Just be myself with others | .75 | .18 | .11 |

| A place where I share any concerns | .70 | .18 | .25 |

| Hang out with others | .59 | .12 | .14 |

| Meet new people or make new friends | .58 | .17 | .31 |

| Do advocacy events in the community | .09 | .73 | .24 |

| Give presentations about LGBT issues or our GSA | .14 | .70 | .07 |

| Speak out for LGBT issues | .19 | .70 | .04 |

| Organize school events to raise awareness of LGBT issues | .24 | .69 | −.03 |

| Work with other student groups on diversity issues | .12 | .68 | .31 |

| Speak out for other minority group issues | .12 | .65 | .26 |

| Educate those not in the GSA on diversity issues | .28 | .58 | .15 |

| Receive training on diversity issues | .28 | .22 | .77 |

| Learn ways to deal with stress | .33 | .20 | .68 |

| Receive resources on services available | .36 | .19 | .67 |

|

| |||

| Eigenvalue | 4.14 | 3.56 | 2.09 |

| % variance accounted for | 24.38% | 20.96% | 12.28% |

Note. Values in bold represent the highest loading across the three factors for each item.

Perceived level of GSA organizational structure

Youth reported their perception of organizational structure in their GSA meetings based on four items, preceded by the stem, “How often does your GSA do these things:” (a) We do check-ins at the beginning of GSA meetings; (b) We follow-up about things that were discussed in the last GSA meeting; (c) Our GSA meetings follow an agenda; and, (d) There is someone who leads our GSA meetings. Response options were: Never, rarely, sometimes, often, and all the time (scaled 0 to 4). Higher average scale scores represent greater perceived organizational structure within GSA meetings. Coefficient alpha reliability was α = .68. Individual perceptions of organizational structure were included as an independent variable at Level 1 (the individual level) and a composite score for each GSA derived from the collective average scores of all the students in that GSA was used at Level 2 (the GSA level) in our multilevel models.

Perceived positive school LGBT climate

Youth responded to six items developed for the survey asking about the LGBT climate of their school, preceded by the stem, “At school, how often do you…”: (a) Hear other students use anti-LGBT language (reverse-scored); (b) Have LGBT issues discussed in your classes; (c) Hear students make negative comments about LGBT people (reverse-scored); (d) Hear teachers make negative comments about LGBT people (reverse-scored); (e) Hear students make positive comments about LGBT people; and, (f) Hear teachers make positive comments about LGBT people. Response options were: Never, rarely, sometimes, often, and all the time (scaled 0 to 4). Higher average scale scores represent a more positive LGBT climate in the school. Coefficient alpha reliability was a = .60.

Sense of agency

Youth completed the six-item State Hope Scale that assesses agency and pathways to achieving goals (Snyder et al., 1996; e.g., “If I should find myself in a jam, I could think of many ways to get out of it” and “At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals”). Response options ranged from 1 (definitely false) to 8 (definitely true). Higher average scale scores represent greater sense of agency. Coefficient alpha reliability was a = .91.

Analytic Strategy

Prior to testing our main hypotheses in our multilevel models, we conducted a series of MANOVAs to identify potential demographic differences based on sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender on our set of variables. As noted, we used the dichotomized categories for race/ethnicity and sexual orientation in our analyses because of the limited sample sizes for specific minority groups and issues of statistical power for the multilevel models. We also examined bivariate correlations among our set of variables.

We constructed several multilevel models using HLM 7.0 to test our main hypotheses. In Model 1, we tested for main effects of independent variables at the individual and group level. At the individual level we included youth demographic variables (sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity) and the following variables that were group-mean centered: grade level, perceived family support, individual perceptions of organizational structure in the GSA, individual perceptions of the LGBT climate of the school, amount of support and socializing received from the GSA, amount of information and resources received from the GSA, and amount of advocacy individuals reported doing in their GSA. Thus, we included the three GSA functions (i.e., support/socializing, information/resources, advocacy) simultaneously in the model. At the group level we included the following variables as independent variables for the Level 2 intercept (i.e., to account for average differences across GSAs in youth’s sense of agency): the collective perceptions of structure in the GSA and school LGBT climate, each based on the composite scores of all youth in the same GSA, and the number of members from each GSA (as a covariate).

In Model 2, we tested whether support/socializing, information/resources, and advocacy were associated with agency differentially for sexual minority and heterosexual youth. To do so, we added an interaction term between sexual orientation and each GSA function as an independent variable to Model 1; one model tested this interaction with support/socializing (Model 2a), a second model tested this interaction with information/resources (Model 2b), and a third model tested this interaction with advocacy (Model 2c). The interaction term was formed from the standardized score of the respective GSA function and the dichotomized sexual orientation variable; the group-mean centered standardized score of that GSA function was included as the main effect in its respective model to reduce issues of multicollinearity.

In Model 3, we tested for the moderating effect of GSA organizational structure on the association between youth’s involvement in GSA functions (i.e., support and socializing, information and resources, and advocacy) and agency. To test for these cross-level moderation effects, in one model we included group structure (at Level 2) as a moderator of the association between support/socializing received (at Level 1) and agency (Model 3a). We tested an analogous model for information and resources (Model 3b) and for advocacy (Model 3c).

Results

Descriptive Statistics, Group Differences, and Bivariate Correlations

The MANOVA testing for sexual orientation differences on our set of variables was significant, Wilks’ Λ = .92, F (7, 249) = 3.13, p < .01, . Follow-up ANOVAs indicated that sexual minority youth reported receiving more support and socializing from the GSA, doing more advocacy in the GSA, and reported a less positive LGBT climate in the school than heterosexual youth (Table 3). The MANOVA for race/ethnicity was significant, Wilks’ Λ = .88, F (7, 250) = 4.82, p < .001, . Follow-up ANOVAs indicated that white youth reported doing more advocacy in the GSA than racial/ethnic minority youth (Table 3). The MANOVA for gender was not significant, Wilks’ Λ = .92, F (14, 500) = 1.49, p = .11. Table 3 also includes descriptive data for all the measures based on sexual orientation and race/ethnicity.

Table 3.

Descriptive Data for Measures based on Sexual Orientation and Race/Ethnicity

| Sexual Orientation | Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Sexual Min. (n = 180) | Heterosexual (n = 77) | F |

|

Racial Min. (n = 80) | White (n = 178) | F |

|

|||

| Agency | 4.98 (1.76) | 5.15 (1.57) | 0.59 | — | 5.22 (1.70) | 4.94 (1.69) | 1.47 | — | ||

| Family support | 4.14 (1.88) | 4.61 (1.97) | 3.49 | — | 3.91 (1.97) | 4.40 (1.89) | 4.03 | — | ||

| Support/Social received | 4.52 (0.58) | 4.32 (0.85) | 4.54* | .02 | 4.37 (0.80) | 4.50 (0.61) | 2.07 | — | ||

| Info/Resources received | 3.71 (1.06) | 3.64 (1.01) | 0.11 | — | 3.79 (1.11) | 3.63 (1.02) | 1.49 | — | ||

| Advocacy done | 3.23 (0.98) | 2.89 (0.87) | 6.57* | .03 | 2.93 (1.02) | 3.21 (0.92) | 5.25* | .02 | ||

| Organizational structure | 3.13 (0.72) | 2.97 (0.70) | 3.16 | — | 2.96 (0.76) | 3.12 (0.70) | 4.01 | — | ||

| LGBT school climate | 1.93 (0.56) | 2.12 (0.50) | 4.29* | .02 | 2.05 (0.60) | 1.95 (0.52) | 2.47 | — | ||

Note. Values represent the means and standard deviations (in parentheses) of scores for each demographic group. Sexual min. = sexual minority youth; Racial min. = racial/ethnic minority youth; Agency = sense of agency; Family support = perceived family support; Support/Social received = amount of support/socializing received from the GSA; Info/Resources received = amount of information and resources received from the GSA; Advocacy done = amount of advocacy done in the GSA; Organizational structure = perceived level of organizational structure within the GSA; LGBT school climate = perceived positive LGBT climate in the school.

p < .05.

Bivariate correlations indicated that all the independent variables were associated with agency. Youth who reported greater family support (r = .38, p < .001), received more support and socializing from the GSA (r = .28, p < .001), received more information and resources from the GSA (r = .21, p < .001), engaged in more advocacy in the GSA (r = .21, p < .001), perceived more organizational structure in the GSA (r = .14, p < .05), perceived a more positive LGBT climate in their school (r = .23, p < .001), and who were in later grade levels (r = .15, p < .05) reported higher sense of agency. Table 4 presents the associations among all the variables and overall descriptive data for the measures.

Table 4.

Bivariate Correlations among the Variables

| Agency | Family support | Sup/Soc received | Info/Res received | Advocacy done | Org. structure | LGBT s-climate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency | — | ||||||

| Family support | .38*** | — | |||||

| Sup/Soc received | .28*** | .17** | — | ||||

| Info/Res received | .21*** | .06 | .56*** | — | |||

| Advocacy done | .21*** | .06 | .44*** | .47*** | — | ||

| Org. structure | .14* | −.02 | .42*** | .46*** | .42*** | — | |

| LGBT s-climate | .23*** | .17** | .17** | .17** | .13* | .10 | — |

| Grade level | .15* | .05 | .04 | −.06 | .08 | −.04 | .09 |

| M (SD) | 5.02 (1.70) | 4.26 (1.92) | 4.46 (0.67) | 3.68 (1.05) | 3.12 (0.96) | 3.07 (0.72) | 1.99 (0.55) |

Note. Agency = sense of agency; Family support = perceived family support; Sup/Soc received = amount of support/socializing received from the GSA; Info/Res received = amount of information and resources received from the GSA; Advocacy done = amount of advocacy done in the GSA; Org. structure = individual perception of organizational structure within the GSA; LGBT s-climate = individual perception of positive LGBT climate in the school; Grade level = student grade level in school. Overall averages and standard deviations (in parentheses) for the scales are included in the final row of the table.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Multilevel Models of Youth Agency

The fully unconditional model indicated that there was significant variance across GSAs in youth agency (χ2 = 66.89, p < .01), with 14% of the total variance in agency at the group level (Level 1 variance component: 2.57; Level 2 variance component: 0.35). Next, we tested our multilevel model with the main effects of our independent variables at the individual and group level (Model 1; Table 5). A number of factors were significantly associated with greater sense of agency among youth. Regarding demographic differences, racial/ethnic minority youth reported greater agency than white youth (b = 0.51, p < .01), and cisgender boys reported greater agency than cisgender girls (b = 0.67, p < .001). Also, students in higher grade levels (b = 0.23, p < .05) and who reported greater perceived family support (b = 0.30, p < .001) reported greater agency. At the group level, youth in GSAs that had more members represented reported lower levels of agency (γ = −0.06, p < .01) and youth in schools that were perceived to have a more positive LGBT climate reported higher levels of agency (γ = 1.00, p < .05). As our main point of interest, even when accounting for the contributions of these other factors, the amount of support and socializing youth received from the GSA (b = 0.25, p = .06) and the amount of advocacy youth did in the GSA (b = 0.24, p < .05) still made distinct contributions that accounted for higher levels of agency. The amount of information and resources received did not make a significant distinct contribution to youth’s level of agency (b = 0.00, p = .95). The amount of variance at Level 1 was reduced to 1.88 and the amount of variance at Level 2 was reduced to 0.31 with the inclusion of these variables. The pseudo-R2 value indicated that our model accounted for 27% of the variance at Level 1 and 11% of the variance at Level 2.

Table 5.

Multilevel Models of Factors Associated with Youth Sense of Agency

| Model 1 Main effects |

Model 2 Interaction between sexual orientation and GSA functions |

Model 3 Cross-level interaction between GSA structure and GSA functions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 2b | 2c | 3a | 3b | 3c | ||

| Level 1 | |||||||

| S. orientation | −0.22 | −0.23 | −0.21 | −0.16 | −0.18 | −0.17 | −0.25 |

| Male | 0.67*** | 0.67*** | 0.66*** | 0.60*** | 0.62*** | 0.58** | 0.60*** |

| Trans/GQueer | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.60 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.51** | 0.51** | 0.53** | 0.49** | 0.47** | 0.49** | 0.50** |

| Grade level | 0.23* | 0.23* | 0.22* | 0.22* | 0.22* | 0.22* | 0.21* |

| Family support | 0.30*** | 0.29*** | 0.30*** | 0.29*** | 0.29*** | 0.29*** | 0.28*** |

| Org. structure | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| LGBT school climate | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

| Sup/Soc received | 0.25† | 0.21 | 0.28* | 0.27* | −1.22* | 0.33** | 0.30* |

| Info/Res received | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.12 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.84 | −0.02 |

| Advocacy done | 0.24* | 0.24* | 0.23* | −0.14 | −0.14 | −0.15 | −0.05 |

| S. O. × Sup/Soc | — | −0.07 | — | — | — | — | — |

| S. O. × Info/Res | — | — | 0.15 | — | — | — | — |

| S. O. × Advocacy | — | — | — | 0.51** | 0.47** | 0.49** | 0.51* |

|

| |||||||

| Level 2 Intercept | |||||||

| Group size | −0.06** | −0.06** | −0.06** | −0.06** | −0.06** | −0.06** | −0.06** |

| Collective org. structure | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.19 |

| Collective LGBT climate | 1.00* | 1.05* | 1.00* | 1.01* | 1.02* | 1.02* | 0.95* |

|

| |||||||

| Cross-level Moderator | |||||||

| G. Structure × Sup/Soc | — | — | — | — | 0.54* | — | — |

| G. Structure × Info/Res | — | — | — | — | — | 0.27 | — |

| G. Structure × Advoc × S. O. | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.51* |

Note. S. orientation = dichotomized as sexual minority (1) or heterosexual (0); Male = dichotomized as cisgender male (1) or not (0); Trans/GQueer = dichotomized as transgender/gender-queer (1) or not (0); Race/ethnicity = dichotomized as racial/ethnic minority (1) or white (0); Grade level = student grade level in school; Family support = perceived family support; Org. structure = perceived organizational structure within the GSA; LGBT school climate = perceived positive LGBT climate in the school; Sup/Soc received = amount of support/socializing received from the GSA; Info/Res received = amount of information and resources received from the GSA; Advocacy done = amount of advocacy done in the GSA; S. O. × Sup/Soc = interaction between sexual orientation and support/socializing received; S. O. × Info/Res = interaction between sexual orientation and information/resources received; S. O. × Advocacy = interaction between sexual orientation and advocacy done; Group size = number of participants in the respective GSA; Collective org. structure = composite average score of perceived level of GSA structure among youth in the same GSA; Collective LGBT climate = composite average score of perceived positive LGBT climate in the school among youth in the same GSA; G. Structure × Sup/Soc = moderating effect of GSA structure (Level 2) on the association between support/socializing received (Level 1) and youth agency; G. Structure × Info/Res = moderating effect of GSA structure (Level 2) on the association between information/resources received (Level 1) and youth agency; G. Structure × S. O. × Advoc = moderating effect of GSA structure (Level 2) on the association between engaging in advocacy (Level 1) and youth agency, which itself is moderated by sexual orientation (Level 1).

p = .06.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Next, we tested whether support and socializing, information and resources, and advocacy were associated with agency equally for sexual minority and heterosexual youth (Models 2a – 2c). As shown in Table 5, the interaction was not significant for support and socializing or information and resources, but it was significant for advocacy (b = 0.51, p < .01). As a follow-up, we tested the advocacy model separately for heterosexual and sexual minority youth and found that greater engagement in advocacy was not associated with sense of agency among heterosexual youth (b = −0.02, p = .94), but it was associated with sense of agency among sexual minority youth (b = .39, p < .01).

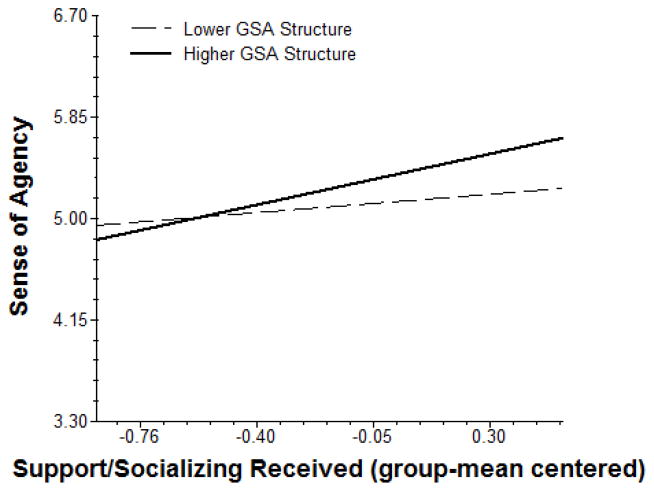

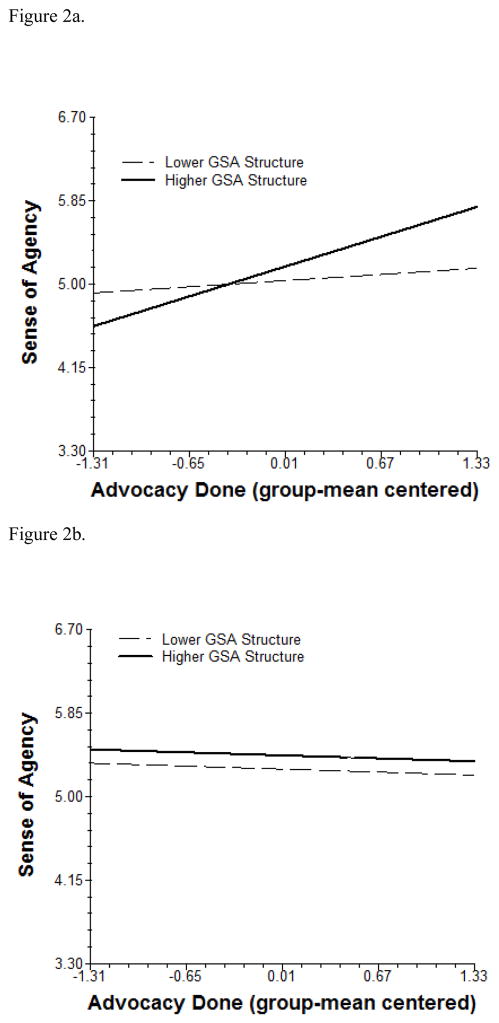

Finally, we tested our hypotheses that the GSA’s level of organizational structure would moderate the extent to which support and socializing, information and resources, and advocacy were associated with youth’s sense of agency (Models 3a–3c; Table 5). In the case of advocacy, we included GSA structure as a moderator of the interaction term between agency and sexual orientation because of its significant effect in the prior analyses. As hypothesized, organizational structure in the GSA moderated the extent to which support and socializing was associated with agency (γ = 0.54, p < .05). As shown in Figure 1, receiving more support and socializing from the GSA was more strongly associated with greater agency for youth in GSAs that had more organizational structure than for youth in GSAs that had less structure. Also as hypothesized, organizational structure in the GSA moderated the extent to which advocacy was associated with agency for sexual minority youth (γ = 0.51, p < .05; i.e., this represented a 3-way interaction in which sexual orientation and advocacy were Level 1 variables and GSA structure was a Level 2 variable). As shown in Figure 2a, doing more advocacy in the GSA was more strongly associated with greater agency for sexual minority youth in GSAs that had more organizational structure than for sexual minority youth in GSAs that had less structure. Advocacy remained unassociated with agency for heterosexual youth regardless of the level of organizational structure in the GSA (Figure 2b). Perceived structure in the GSA did not moderate the extent to which receiving more information and resources was associated with agency (γ = 0.27, p = .17).

Figure 1.

Cross-level moderating effect of GSA organizational structure (Level 2) on the association between support/socializing received in the GSA (Level 1) and youth’s sense of agency. Low and high levels of GSA structure are represented by the lower and upper quartiles of the scale scores.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Cross-level moderating effect of GSA organizational structure (Level 2) on the association between advocacy done in the GSA (Level 1) and sense of agency for sexual minority youth. Low and high levels of GSA structure are represented by the lower and upper quartiles of the scale scores.

Figure 2b. Non-significant cross-level moderating effect of GSA organizational structure (Level 2) on the association between advocacy done in the GSA (Level 1) and sense of agency for heterosexual youth. Low and high levels of GSA structure are represented by the lower and upper quartiles of the scale scores.

Discussion

Comparison studies have suggested that the presence of GSAs in schools is associated with lower psychosocial concerns. Our study built on these findings by departing from the standard approach of treating GSAs as monolithic entities or assuming homogeneity among youth; instead, we considered specific functions of GSAs that could relate to variability in agency among GSA members (i.e., belief in one’s capacity to initiate and sustain actions; Snyder et al., 1996). As hypothesized, youth who received more support and socializing, information and resources, and who did more advocacy in their GSA reported greater agency. Support and socializing and advocacy uniquely contributed to youth’s agency even while controlling for the contribution of family support and positive LGBT school climate. Adding nuance to the case for advocacy, we found that advocacy was associated with agency for sexual minority youth but not for heterosexual youth. Finally, greater organizational structure in the GSA enhanced the association between support and socializing and agency; it also enhanced the association between advocacy and agency for sexual minority youth. These findings begin to provide empirical support for specific functions of GSAs that could promote wellbeing and suggest conditions under which their effects may be enhanced.

Support and Socializing in Relation to Youth Agency

GSAs have been long regarded as a setting meant for sexual minority youth to feel safe and supported, with opportunities to interact with peers without fear of rejection (Griffin et al., 2004). Youth program models consider such environments a foundational necessity (Dawes & Larson, 2011; Eccles & Gootman, 2002). In line with our hypothesis, youth who perceived receiving more support and socializing from their GSA reported a greater sense of agency. This association was significant over and above associations of family support and the broader LGBT climate of the school. This effect specific to GSA support may have been evident because peers are a primary source of support and socializing during adolescence (Berndt, 2002). Receiving support and encouragement in the GSA may have been critical for sexual minority youth, many of whom may have faced rejection in other contexts that would have prevented them from expressing themselves or pursuing their interests (i.e., developing a sense of agency). Further, this association was as strong for heterosexual youth. In addition to serving as allies, some heterosexual youth join GSAs because they, too, are marginalized based on other aspects of identity (Griffin et al., 2004; Miceli, 2005; Russell et al., 2009). Similarly, heterosexual youth in general benefit from peer support and socializing during adolescence, which often occurs in extracurricular settings (Feldman & Matjasko, 2005; Fredricks & Eccles, 2005).

Of importance, the association between receiving support and socializing in the GSA and youth’s sense of agency was stronger for youth in GSAs with greater organizational structure. Our finding aligns with another tenet of youth program models that there must be adequate structure for programs to be effective (Catalano et al., 2004; Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Wood et al., 2009). In this case, organizational structure was reflected by items such as having check-ins at the start of meetings and following-up on prior meetings. These elements of structure may have ensured that youth with pressing concerns could be heard and given sufficient time to receive support or to follow-up on past experiences to ensure greater continuity of care. Thus, as expected, although organizational structure did not have a direct association with youth’s agency, it did magnify the extent to which several GSA functions intended to promote wellbeing – in this case support and socializing and, as we later note, advocacy – were related to agency.

Information and Resources in Relation to Youth Agency

The resource provision-based function of GSAs has been given arguably less attention than their support and socializing or advocacy functions. Unlike these other two functions, receiving more information and resources in the GSA did not contribute uniquely to youth’s agency in the multilevel model; yet, its bivariate association with agency was significant. There are several possible explanations for this finding. Information or resources delivered in GSAs may themselves need to be refined to strengthen their utility. Alternatively, youth might have gained similar knowledge indirectly through advocacy or from peer support. Also, it could be important to include a more comprehensive measure of resources. Finally, this association may vary based on types of resources. Despite its relatively weaker contribution in the multilevel model, the strength of its bivariate association with agency was similar to the bivariate associations of support and socializing and advocacy with agency.

The part of the overall mission of GSAs to provide resources to members remains important. Many schools do not use inclusive curricula that represent LGBT individuals or issues (Russell et al., 2010). Although this function of GSAs did not contribute to youth’s agency over and above other factors, it could do so for other outcomes such as engagement in risky sexual behavior or substance use. GSA presence in schools has been connected to lower levels on both of these risk behaviors (Heck et al., 2014; Poteat et al., 2013), which could be on account of the information and resources made available through GSAs. Thus, attention to this GSA function remains warranted.

Advocacy in Relation to Youth Agency

We expected the association between advocacy and agency because many advocacy efforts in GSAs require youth to engage in roles that promote agency (e.g., taking on leadership, expressing one’s beliefs and taking a stand to change larger social problems; Miceli, 2005; Russell et al., 2009), and youth have reported feeling empowered through their advocacy in GSAs (Russell et al., 2009). We found, however, that this association was only significant for sexual minority youth and not for heterosexual youth. This qualification deserves greater attention, given the growing emphasis on advocacy in youth programs (Fields & Russell, 2005; Ginwright, 2007; Inkelas, 2004). In contrast to support and socializing, which are universally beneficial to all youth, advocacy efforts in GSAs often seek to counter stressors that more often affect sexual minority youth (e.g., homophobic harassment). Consequently, these actions may have been more beneficial for sexual minority youth because they reduced stressors that would have otherwise diminished agency disproportionately among sexual minority youth. Similarly, the success of an advocacy effort may be perceived as more important among LGBT youth than their heterosexual allies. At the same time, heterosexual allies may derive other benefits from advocacy (e.g., developing skills such as goal setting, confidence, strengthening their sense of community with peers). Given that GSAs are also intended for heterosexual youth, more research is needed on their experiences in GSAs, how GSAs meet their particular needs and interests, and identifying the potential benefits that they derive from their involvement.

As with support and socializing, the association between doing more advocacy in the GSA and greater agency was stronger for youth in GSAs with greater organizational structure. Advocacy efforts in GSAs often require coordinated efforts among many youth and take multiple meetings to plan and implement (e.g., Ally Week, No Name-Calling Week, ThinkB4YouSpeak; GLSEN, n.d.). Thus, the indices of organizational structure as assessed in this study (i.e., having regular check-ins, follow-ups, agendas, having someone to facilitate meetings) were likely critical to ensure continuity across meetings and sustainability of collaborations both within and external to the GSA. Observational data have suggested that a balance of structure (e.g., agenda setting) and flexibility for addressing new or pressing issues may be optimal in GSA settings (Poteat et al., 2015). Overall, our findings for the significant effect of organizational structure in relation to how support and socializing as well as advocacy were associated with youth’s agency underscore its relevance and the need to focus on identifying optimal levels of structure.

Strengths, Limitations, Future Directions

Despite the increasing number of GSAs across the U.S., there remain few studies that have examined how they operate or that provide data on what specific factors relate to their effectiveness. The major strength of the current study was to move from the standard approach of looking simply at GSA presence to identifying specific functions of GSAs associated with members’ sense of agency. Further, we controlled for other major contributors to youth agency, including parental support and the broader school climate, for a more rigorous test of the distinct contributions of these GSA functions. In addition, we considered greater nuance in these associations in two ways: (a) we identified similarities and differences between sexual minority and heterosexual youth in how strongly these functions were associated with their agency, and (b) we identified variability across GSAs in how strongly these functions were associated with youth agency based on the GSA’s level of organizational structure. Finally, we used a multilevel modeling approach; scholars have called for more youth programs research to use this kind of approach to examine individual and contextual factors as well as their interaction in relation to positive youth development (Ramey & Rose-Krasnor, 2012).

There were also limitations to this study. First, while the GSAs were located across diverse regions, they were all located in Massachusetts. Research should test whether these patterns extend to GSAs in other areas of the country and consider even broader contextual factors that could moderate the extent to which GSA functions relate to youth agency (e.g., political climate, state laws). Second, the data were cross-sectional, limiting our ability to make causal statements. Although we based our models on established youth program models and theory, it would be beneficial for longitudinal research to look at reciprocal causal associations. For instance, greater agency could lead some youth to be more social and supportive of other members. Our identification of these associations represents an important step in this ongoing process. Third, while our comparison of sexual minority and heterosexual youth was based on the particular nature of GSAs, it would be important to consider whether youth from other social backgrounds benefit equally from their involvement in specific GSA functions. We were unable to consider additional intersecting social identities such as those of specific racial/ethnic groups, due to smaller sample sizes. For similar reasons, the sample sizes for specific sexual-minority subgroups were not large enough for reliable comparisons in our models. Fourth, the reliability estimates for the measures of structure and climate were weaker than preferred. However, we would expect that this lower reliability would pose a threat to validity by attenuating significant associations; because we still found significant associations of these variables in the manner hypothesized, this threat to validity may be less of a concern. Still, future studies should seek to include more robust measures. Fifth, data were youth self-reported and from a convenience sample of youth who attended regional conferences or who were motivated enough to complete the survey available from their advisor. Specific to youth who attended these conferences, these youth may be more likely to be out to their parents, have more resources, be involved in leadership roles, or be in GSAs that are more organized or receive more funding and support from administrators. Thus, future studies should include multi-informant data from advisors and should include youth who may be less involved in their GSA or who may have had negative experiences in the group, as well as GSAs that may have fewer resources or that are less established than those in the current study. The greater representation of these youth could capture more variance in youth’s reported agency and across the other independent variables. Finally, although we considered how three overarching and core facets of GSAs (i.e., support/socializing, information/resources, and advocacy) were associated with agency, these do not capture all the ways in which youth involvement in GSAs may promote agency. For instance, future studies should consider other factors such as holding a formal leadership role or taking on leadership responsibilities on specific tasks and whether this may uniquely contribute to agency or moderate the effects of involvement in the three overarching facets that we examined.

Conclusion

Developmental research has documented support for the role of youth programs and settings in promoting youth development; however, little of this research has included programs that address sexual orientation issues or that serve sexual minority youth. Yet, especially in school settings, these programs face unique challenges and hostility, and youth involved in them have varied interests and needs that they look to the GSA to meet. As part of addressing this limitation in the literature, we found that three major GSA functions (support/socializing, information/resource provision, and advocacy) were associated with agency among GSA members and that some of these associations were stronger for members in GSAs with greater structure. Continued research in this area needs to consider how GSAs can flexibly meet the varied needs of youth and whether GSAs are equally beneficial for specific populations of LGBQ and heterosexual youth, as well as for transgender and cisgender youth. Such advances are needed in order to ensure that GSAs and other programs serving these youth rely on empirically-supported practices to shape their efforts. Attention to specific components of GSAs that promote positive outcomes could highlight how GSAs can be successful at promoting positive development across the diverse youth in them while attending to youth’s varied needs and strengths. These ongoing efforts to study GSAs stand to contribute to the larger aim of promoting the healthy development of sexual minority and heterosexual youth in the many contexts in which they develop.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participating GSAs, the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth, Jeff Perrotti, and Arthur Lipkin for their roles in and support of the Massachusetts GSA Network project.

Funding

Support for the writing of this manuscript was partially based on funding awarded from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), 1R01MD009458-01, to Poteat (Principal Investigator) and Calzo and Yoshikawa (Co-Investigators). Additional support for the second author (Calzo) was provided by funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), K01DA034753.

Biographies

V. Paul Poteat is Associate Professor in the Department of Counseling, Developmental, and Educational Psychology at Boston College. His research on Gay-Straight Alliances has identified specific individual, group, advisor, and school factors that contribute to youth members’ experiences in GSAs and the mechanisms by which GSAs promote youths’ wellbeing. His work also examines homophobic bullying as well as affirming behavior among heterosexual youth allies.

Jerel P. Calzo is Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and Research Associate in Adolescent Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital. His research examines the development of gender and sexual orientation health disparities in adolescence and young adulthood, with a focus on promoting health in heterosexual and sexual minority males and developing school and community-based programs to support the health and positive youth development of gender and sexual minority adolescents and young adults.

Hirokazu Yoshikawa is the Courtney Sale Ross University Professor of Globalization and Education at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development. He studies Gay-Straight Alliances and their associations with youth development. In addition, he examines the effects of programs related to immigration, early childhood development, and poverty reduction on children and youth in the United States as well as in low- and middle-income countries. He co-directs the Global TIES for Children Center at New York University.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing of the manuscript, as well as to the interpretation of the statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval

Approval for secondary data analysis was granted by the Boston College Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent

GSA advisors granted adult consent for all youth who participated in completing the survey.

Contributor Information

V. Paul Poteat, Email: PoteatP@bc.edu, Boston College

Jerel P. Calzo, Email: Jerel.Calzo@childrens.harvard.edu, Boston Children’s Hospital

Hirokazu Yoshikawa, Email: hiro.yoshikawa@nyu.edu, New York University.

References

- Berndt TJ. Friendship quality and social development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Berglund ML, Ryan JAM, Lonczak HS, Hawkins JD. Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;591:98–124. [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Stafford MBR, Pullig C. How Gay-Straight Alliance groups mitigate the relationship between gay-bias victimization and adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes NP, Larson R. How youth get engaged: Grounded-theory research on motivational development in organized youth programs. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:259–269. doi: 10.1037/a0020729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Gootman JA. Community programs to promote youth development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AF, Matjasko JL. The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of Educational Research. 2005;75:159–210. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields J, Russell ST. Queer, sexuality, and gender activism. In: Sherrod LR, Flanagan CA, Kassimir R, editors. Youth activism: An international encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 2005. pp. 512–514. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Eccles JS. Developmental benefits of extracurricular involvement: Do peer characteristics mediate the link between activities and youth outcomes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:507–520. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S. Black youth activism and the role of critical social capital in Black community organizations. The American Behavioral Scientist. 2007;51:403–418. [Google Scholar]

- GLSEN. About gay-straight alliances. n.d Retrieved from http://www.glsen.org.

- Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O’Brien MU, Zins JE, Fredericks L, Resnik H, Elias MJ. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist. 2003;58:466–474. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P, Lee C, Waugh J, Beyer C. Describing roles that Gay-Straight Alliances play in schools: From individual support to social change. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education. 2004;1:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman JB, Tierney JP. Does mentoring work? An impact study of the Big Brothers Big Sisters program. Evaluation Review. 1998;22:403–426. [Google Scholar]

- GSA Network. National directory. n.d Retrieved from http://www.gsanetwork.org.

- Heck NC, Flentje A, Cochran BN. Offsetting risks: High school Gay-Straight Alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. School Psychology Quarterly. 2011;26:161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Lindquist LM, Stewart BT, Brennan C, Cochran BN. To join or not to join: Gay-Straight Student Alliances and the high school experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2013;25:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Livingston NA, Flentje A, Oost K, Stewart BT, Cochran BN. Reducing risk for illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse: High school gay-straight alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:824–828. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inkelas KK. Does participation in ethnic cocurricular activities facilitate a sense of ethnic awareness and understanding? A study of Asian Pacific American undergraduates. Journal of College Student Development. 2004;45:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Koepke S, Denissen JJA. Dynamics of identity development and separation-individuation in parent-child relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood – A conceptual integration. Developmental Review. 2012;32:67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW. Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist. 2000;55:170–183. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R. Positive youth development, willful adolescents, and mentoring. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:677–689. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Angus RM. Adolescents’ development of skills for agency in youth programs: Learning to think strategically. Child Development. 2011;82:277–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JL, Harris AL, Eccles JS. Organized activity participation, positive youth development, and the over-scheduling hypothesis. SRCD Social Policy Report. 2006;20:3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Miceli M. Standing out, standing together: The social and political impact of Gay-Straight Alliances. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:673–686. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce NJ, Larson RW. How teens become engaged in youth development programs: The process of motivational change in a civic activism organization. Applied Developmental Science. 2006;10:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Sinclair KO, DiGiovanni CD, Koenig BW, Russell ST. Gay-Straight Alliances are associated with student health: A multi-school comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2013;23:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Yoshikawa H, Calzo JP, Gray ML, DiGiovanni CD, Lipkin A, Mundy-Shephard A, Perrotti J, Scheer JR, Shaw MP. Contextualizing Gay-Straight Alliances: Student, advisor, and structural factors related to positive youth development among members. Child Development. 2015;86:176–193. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey HL, Rose-Krasnor L. Contexts of structured youth activities and positive youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Beyond risk: Resilience in the lives of sexual minority youth. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Issues in Education. 2005;2:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Kosciw J, Horn S, Saewyc E. Safe schools policy for LGBTQ students. Society for Research in Child Development Social Policy Report. 2010;24(4):3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Muraco A, Subramaniam A, Laub C. Youth empowerment and high school Gay-Straight Alliances. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:891–903. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9382-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM. Research on adolescent sexual orientation: Development, health disparities, stigma, and resilience. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:256–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Sympson SC, Ybasco FC, Borders TF, Babyak MA, Higgins RL. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:321–335. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taines C. Intervening in alienation: The outcomes for urban youth of participating in school activism. American Educational Research Journal. 2012;49:53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Russell ST. Gay-Straight Alliances, social justice involvement, and school victimization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer youth: Implications for school well-being and plans to vote. Youth & Society. 2013;45:500–522. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11422546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls NE, Kane SB, Wisneski H. Gay-Straight Alliances and school experiences of sexual minority youth. Youth & Society. 2010;41:307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Watson LB, Varjas K, Meyers J, Graybill EC. Gay-Straight Alliance advisors: Negotiating multiple ecological systems when advocating for LGBTQ youth. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2010;7:100–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wood D, Larson RW, Brown JR. How adolescents come to see themselves as more responsible through participation in youth programs. Child Development. 2009;80:295–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]