Abstract

We contribute to the literature on the relations of temperament to externalizing and internalizing problems by considering parental emotional expressivity and child gender as moderators of such relations and examining prediction of pure and co-occurring problem behaviors during early to middle adolescence using bifactor models (which provide unique and continuous factors for pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems). Parents and teachers reported on children’s (4.5- to 8-year-olds; N = 214) and early adolescents’ (6 years later; N = 168) effortful control, impulsivity, anger, sadness, and problem behaviors. Parental emotional expressivity was measured observationally and with parents’ self-reports. Early-adolescents’ pure externalizing and co-occurring problems shared childhood and/or early-adolescent risk factors of low effortful control, high impulsivity, and high anger. Lower childhood and early-adolescent impulsivity and higher early-adolescent sadness predicted early-adolescents’ pure internalizing. Childhood positive parental emotional expressivity more consistently related to early-adolescents’ lower pure externalizing compared to co-occurring problems and pure internalizing. Lower effortful control predicted changes in externalizing (pure and co-occurring) over 6 years, but only when parental positive expressivity was low. Higher impulsivity predicted co-occurring problems only for boys. Findings highlight the probable complex developmental pathways to adolescent pure and co-occurring externalizing and internalizing problems.

Concurrent and longitudinal relations between temperament and externalizing and internalizing problems are well supported. Primarily guided by the vulnerability or resilience model, many researchers have tested whether temperamental characteristics represent a predisposition for, or protection against, certain types of psychopathology (see Nigg, 2006; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). In addition, the environment may serve as a risk or protective factor in the relation between temperament and psychopathology (e.g., Bates, Schermerhorn, & Petersen, 2012; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Temperamental characteristics may also be perceived or experienced differently for boys or girls, and thus the role of temperament in psychopathology may differ across gender (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006). Examining whether relations between temperament and early adolescent problem behaviors are moderated by environmental factors, or are specific to boys or girls, is necessary for better understanding the development of problem behaviors and might be useful in tailoring preventive interventions.

Role of Temperament in Problem Behaviors

Temperament is defined as “constitutionally-based individual differences in reactivity and regulation” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, p. 100). The regulatory component of temperament is effortful control, defined as ”the efficiency of executive attention—including the ability to inhibit a dominant response and/or to activate a subdominant response, to plan, and to detect errors” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, p. 129). Effortful control includes inhibitory control (the capacity to suppress approach responses under instruction and to plan), attentional shifting (the capacity to willfully shift attention under task demands), and attentional focusing (the capacity to maintain attentional focus; Derryberry & Rothbart, 1988), as well as some aspects of executive functioning. Several aspects of temperament reflect “reactivity,” including impulsivity (speed of response initiation; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994), frustration/anger, and sadness. These latter two are aspects of negative emotionality describing one’s propensity to experience these aversive emotions.

There is reasonable consensus regarding the relations between temperament and problem behaviors, especially in childhood. Research suggests that higher levels of negative emotionality (e.g., anger and sadness) are related to greater internalizing and externalizing problems (Colder & Stice, 1998; Muris, Meesters, & Blijlevens, 2007; Ormel et al., 2005). Anger is positively associated with reactive aggression, and aggression is a core feature of externalizing problems (Crick & Dodge, 1996). Children with externalizing problems also often have less success achieving academic and social goals and prompt negative responses from others, potentially eliciting sadness (Capaldi, 1991). For children with internalizing problems, dispositional anger may intensify over time due to peer rejection or other consequences of being withdrawn, sad, or inhibited. Eisenberg et al. (2005) obtained findings suggesting that anger might stem from internalizing problems. Anger also might reflect a propensity toward hostility or resentful affect that stems from fear and stress, which are both traits that underlie internalizing problems (Nigg, 2006). Finally, not only might children high in sadness be predisposed to experience internalizing problems (e.g., depression), but negative consequences stemming from inhibition or withdrawal may also increase sadness.

Deficits in self-regulation and effortful control may better predict externalizing than internalizing problems (Janson & Mathiesen, 2008; Spinrad et al., 2007). Low effortful control might result in lowered social-information processing abilities, a risk factor for externalizing problems (Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006). The inability to inhibit inappropriate behaviors also likely increases the expression of disruptive or aggressive behaviors across contexts. Research with internalizing problems is more inconsistent, with some studies finding that greater effortful control positively (Murray & Kochanska, 2002) or negatively (Eisenberg et al., 2004; Muris et al., 2007) predicts greater internalizing problems. Perhaps this inconsistency is because internalizing problems are heterogeneous and include anxiety, somatic, and depressive symptoms, due to different patterns with age, or because certain aspects of effortful control (e.g., attentional control) are more important than other aspects (e.g., inhibitory control) in predicting internalizing problems (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2004). Moreover, most investigators have not examined the relation of effortful control to internalizing problems that do not co-occur with externalizing problems.

Research has shown that higher levels of impulsivity predicted greater externalizing, but fewer internalizing, problems (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2004; Krueger, Markon, Patrick, Benning, & Kramer, 2007). Impulsivity loads on the higher order temperamental factor of surgency, which has been posited to reflect the relative activation of the behavioral activation systems (BAS) and behavioral inhibition systems (e.g., Gray, 1990). Impulsivity has also been thought to reflect one’s reactive control, a more involuntary and inflexible form of control leading to overly rigid and inhibited behavior or to overly approach- and reward-driven behavior (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002). Thus, impulsive children may be at risk for externalizing problems due to high reward sensitivity (high BAS and reactive undercontrol) and low punishment sensitivity (low behavioral inhibition system). Impulsivity has been identified as a phenotype that underlies the externalizing spectrum (Krueger et al., 2007). Conversely, low impulsivity is viewed as a form of overcontrolled and constrained behavior, which is characteristic of children with internalizing problems (i.e., reactive overcontrol; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2004, 2005, 2009; Kagan, 1998). In addition, children low in BAS (i.e., low impulsivity) may have low positive affect (Gray, 1990), thus increasing their vulnerability for depressive symptoms (e.g., Clark & Watson, 1991).

Parenting and Gender as Moderators of the Relation Between Temperament and Problem Behaviors

However, children’s temperamental characteristics do not act in isolation and may be exacerbated or reduced by environmental or gender differences. Gaining a better understanding of these processes may inform the etiology of problem behaviors. Doing so could also influence decisions to target certain aspects of the environment that appear most likely to buffer or exacerbate the effects of temperament or to implement certain preventive interventions with boys and/or girls.

One important aspect of the environment that may serve as a moderator is parental emotional expressivity, defined as “a persistent pattern or style in exhibiting nonverbal and verbal expressions that often but not always appear to be emotion related” (Halberstadt, Cassidy, Stifter, Parke, & Fox, 1995, p. 93). Parents’ positive emotional expressivity has been related to lower internalizing and externalizing problems both directly and through effortful control (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Lindahl, 1998; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994; Scaramella, Conger, & Simons, 1999; Valiente et al., 2006). Perhaps these relations are due to the role of positive parental expressivity on children’s ability to self-sooth, cope successfully, and self-regulate (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Garner, 1995; Kliewer, Fearnow, & Miller, 1996). Parental positivity also likely fosters a positive parent–child relationship, wherein children are more responsive to parental influence (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Kochanska, 1997, 2002). Note that the role of parents’ negative emotional expressivity in adjustment is less consistent, with some finding that it predicts greater, and others fewer, internalizing- and externalizing-related outcomes (Cooley, 1992; Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Greenberg et al., 1999; Satsky, Bell, & Garrison, 1998; Teti & Cole, 1995). Perhaps when parents occasionally express moderate negative emotions and also model appropriate coping, children learn about emotions and how to regulate them, whereas more intense and chronic negative expressions are detrimental (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Halberstadt, Crisp, & Eaton, 1999; Valiente et al., 2004).

Research suggests that parents’ emotional expressions may act as a risk-enhancing or risk-buffering factor in the relation between temperament and psychopathology (Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011). In general, researchers have found that the combination of higher anger and lower positive/higher negative parental emotional expressions have predicted the greatest levels of externalizing and internalizing problems (Lengua, 2008; Morris et al., 2002; Rubin, Burgess, Dwyer, & Hastings, 2003; Sentse, Veenstra, Lindenberg, Verehulst, & Ormel, 2009; Veenstra, Lindenberg, Oldehinkel, De Winter, & Ormel, 2006). Similarly, children with both low effortful control/regulation and lower positive/higher negative parental emotional expressions were found to have the greatest levels of problem behaviors (e.g., Hastings et al., 2008; Kiff, Lengua, & Bush, 2011; Morris et al., 2002; Van Leeuwen, Mervielde, Braet, & Bosmans, 2004). The combination of higher impulsivity and lower positive/higher negative parental emotions might be a specificrisk factor forexternalizing-related problems (Cipriano & Stifter, 2010; Stice & Gonzales, 1998). Conversely, there is less evidence of interactions between sadness and parental warmth or hostility in predicting problem behaviors (Karreman, de Haas, Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, 2010; Muhtadie, Zhou, Eisenberg, & Wang, 2013). Note that these studies differed in whether they tested parenting or temperament as the moderator. However, taken together, results are consistent with the dual-risk model, which suggests that low positive/high negative parental expressions may amplify preexisting temperamental risk (Sameroff, 1983).

Researchers have also highlighted the importance of considering gender as a moderator of the relation between temperament and problem behaviors (Sanson, Hemphill, Yagmurlu, & McClowry, 2011). Boys typically have lower effortful control, somewhat higher surgency (the higher order factor that contains impulsivity), and higher externalizing problems than do girls (Bongers, Koot, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2003; Else-Quest et al., 2006; Lemery, Essex, & Smider, 2002). To the extent that these mean-level differences also reflect differences in variability, some relations between temperament and problem behaviors might be stronger, or only present for, boys or girls. Therefore, effortful control and impulsivity might predict externalizing problems more strongly for boys than for girls. Researchers also have proposed that the etiological role of temperament in the development of psychopathology might differ for boys and girls, such that lower effortful control and higher negative affectivity predict externalizing for boys, but internalizing for girls (Carver, Johnson, & Joorman, 2008; Else-Quest et al., 2006). Although some research has supported these hypotheses (e.g., Rothbart et al., 1994), other studies have produced different patterns of gender moderation. For instance, researchers have found that different indicators of negative emotionality more strongly predicted conduct problems for boys (i.e., fussiness) and girls (i.e., fearfulness; e.g., Lahey et al., 2008), that frustration more strongly predicted depression for boys than for girls (Oldehinkel, Veenstra, Ormel, de Winter, & Verhulst, 2006), and that effortful control did not differentially predict externalizing problems for boys and girls (Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005; Valiente et al., 2003). Thus, more work is needed to elucidate these relations.

Considering the Co-occurrence Between Externalizing and Internalizing Problems

Researchers who examined prediction by temperament and/or moderation by parenting or gender most frequently utilized separate, continuous measures of externalizing and internalizing. This is a limitation because these problem behaviors co-occur at a higher rate than expected by chance in childhood and adolescence. Co-occurrence is observed in both nonclinical and clinical samples, suggesting that it is not merely accounted for by selection bias (Caron & Rutter, 1991; Lilienfeld, 2003). Individuals with elevated levels of both internalizing and externalizing problems often experience worse outcomes when compared with individuals with elevated levels of only internalizing or externalizing problems (see Nottelman & Jensen, 1995). At the same time, other researchers have found that children with co-occurring problems had better inhibition of reward-seeking behavior and lower callous–unemotional traits when compared to pure externalizers (O’Brien & Frick, 1996). Therefore, it is important to study the etiological precursors of pure and co-occurring problem behaviors.

Researchers who have focused on co-occurrence have found that groups of children with pure externalizing and co-occurring externalizing and internalizing generally share more temperamental risk factors than either group shares with children with pure internalizing. Compared to control children (e.g., children with low externalizing and internalizing), children with pure externalizing and co-occurring problems tend to have lower effortful control, higher impulsivity, higher anger, and higher sadness (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005, 2007, 2009; Oldehinkel, Hartman, de Winter, Veenstra, & Ormel, 2004). Compared to control children, children with pure internalizing problems tend to be higher in sadness and anger and lower in impulsivity (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005, 2009; Oldehinkel et al., 2004). Although some researchers found that pure internalizing children did not differ from control children in effortful control by middle to late elementary school (Eisenberg et al., 2005, 2009), another study found that pure internalizers were lower in effortful control in early adolescence (Oldehinkel et al., 2004). Presumably, many of the theoretical explanations for links between temperament and separate measures of problem behaviors explain their links with pure forms, and at least some apply to co-occurring problems.

A key limitation of the aforementioned previous studies is the use of cutoffs to create categorical problem behavior groups. Given the importance of examining pure and co-occurring problems, it is crucial to characterize co-occurrence in ways that align with current notions that psychological problems are dimensional. One method that addresses these concerns is the bifactor model. Bifactor model is a term used to describe a factor model with one general factor that encompasses all of the factor indicators and some number of specific factors that each encompasses only a subset of the factor indicators (Chen, West, & Sousa, 2006). To model co-occurrence, all problem behavior indicators would load onto a general or co-occurring problems factor, the internalizing indicators would load onto a specific or pure internalizing factor, and the externalizing indicators would load onto a specific or pure externalizing factor. Factors are specified as orthogonal so that each represents unique variance after partialling out variance attributable to the other factors. Factors are also free of error and continuous.

A couple of studies to our knowledge have used the bifactor model to test etiological risks for pure and co-occurring problems. Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge, and Pettit (2003) found that greater behavioral inhibition during infancy predicted greater pure internalizing and fewer pure externalizing problems. Resistance to control in infancy and parents’ harsh punishment predicted greater pure externalizing problems. Those with co-occurring problems were more similar to those with pure externalizing than pure internalizing problems. Similarly, Wang, Chassin, Eisenberg, and Spinrad (2015) found prospective main effects of lower childhood impulsivity and effortful control on adolescent pure depressive symptoms and co-occurring problems, and of lower effortful control on pure aggressive/antisocial behaviors. However, three-way interactions revealed that, only for older adolescents, the combination of low effortful control and high or mean levels of impulsivity predicted both pure aggressive/antisocial and co-occurring problems.

Thus, studies examining co-occurrence have clarified some relations with temperament, but important gaps remain. Few researchers have examined whether parenting moderates the relation between childhood temperament and early-adolescent pure and co-occurring problems. This work could clarify the etiology and specificity of temperament on pure and co-occurring problem behaviors. As one example, low effortful control may be a general risk factor for all types of problem behaviors (e.g., Wang et al., 2015). However, perhaps effortful control when exacerbated by low positive/high negative parental expressivity is a specific risk factor for pure externalizing problems and/or co-occurring problems because children who are dysregulated model their parents’ negative and hostile expressions in inappropriate ways. Furthermore, few researchers, to our knowledge, have examined whether childhood temperament predicts early-adolescent pure versus co-occurring problems differently for boys or girls. Research on this topic has been somewhat inconclusive (e.g., Lahey et al., 2008; Oldehinkel et al., 2006; Rothbart et al., 1994; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). However, perhaps gender differences would become clearer after accounting for the potential confounding influence of co-occurrence and reveal etiological differences in the development of problem behaviors for boys and girls.

There is little research on the concurrent relations between temperament and problem behaviors using a bifactor model in early adolescence, a time when internalizing and externalizing problems are increasing and their temperamental correlates may change (Cohen et al., 1993; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005, 2009; Oldehinkel et al., 2004). Understanding whether concurrent relations using a bifactor model are similar or different to those found previously may provide increased confidence, or directions for future research, in the basic emotional and behavioral difficulties of adolescents with certain problem behaviors. Moreover, we wanted to compare the pattern of concurrent temperament–maladjustment relations with those obtained in the same sample at younger ages to examine potential developmental shifts in these associations. In addition, although prospective analyses controlling for prior levels of problem behaviors can provide support for the vulnerability or resilience model, they may obscure temperament-to-psychopathology relations that arise for other reasons, such as common causes (e.g., spectrum model; Nigg, 2006). The concurrent analyses using a bifactor model can elucidate more general associations between temperament and psychopathology that may reflect these other reasons.

Understanding such processes can also be informative in regard to the cause of co-occurrence. Causes of co-occurrence include the following: (a) one problem behavior causes the other, (b) they are influenced by shared or correlated risk factors, and (c) the co-occurring and one of the pure presentations share the same etiology (Caron & Rutter, 1991). Examining predictors of pure and co-occurring problems cannot completely rule out certain causes of co-occurrence, but can help identify the most likely explanation(s). For example, if the co-occurring and one of the pure presentations are predicted by the same temperamental and environmental factors, this suggests that they share a similar etiology. If all three are predicted by different profiles, this suggests they are distinct. If a certain temperamental characteristic is moderated by an environmental factor to predict, for example, pure externalizing, but only has a main effect on co-occurring problems, this suggests that pure externalizing and co-occurring problems share this temperamental risk, but are differentiated by their amenability to an environment variable. Finally, certain gender moderation patterns may indicate that causes of co-occurrence differ for boys and girls.

The Present Study

The current study was designed to fill several gaps in the literature. One primary goal was to characterize early-adolescent externalizing and internalizing co-occurrence using a bi-factor model. We examined prediction of early-adolescent pure and co-occurring problem behaviors by early-adolescent effortful control, impulsivity, anger, and sadness and whether these relations were moderated by gender. This is an extension of previous studies because in the present study we examined concurrent relations in early adolescence using a bi-factor model. Similar to what has been found in previous studies (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005, 2009; Oldehinkel et al., 2004), we tentatively expected early-adolescents’ low effortful control, and high impulsivity, sadness, and anger to predict pure externalizing and co-occurring problems. In addition, it seemed possible that high impulsivity might especially predict pure externalizing. We expected early-adolescents’ low impulsivity, high sadness, and perhaps high anger, to predict early-adolescent pure internalizing. We expected that the relation of low effortful control to pure internalizing might become more evident concurrently in early adolescence than in elementary school (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2009) because internalizing problems increase in adolescence. We hypothesized that high impulsivity would predict externalizing (pure and co-occurring) more strongly for boys than for girls. Based on previous theorizing (Carver et al., 2008; Else-Quest et al., 2006), we hypothesized that high anger and sadness and low effortful control might predict externalizing (pure and co-occurring) for boys, but pure internalizing for girls. We did not test for prediction by parental expressivity in early adolescence because it was not measured at this age.

We also examined main and interactive effects of childhood temperament and parental emotional expressivity in predicting change in early adolescent pure and co-occurring factors over 6 years (by controlling for childhood internalizing and/or externalizing). Note that our operationalization of parental expressivity included aspects of positive and negative emotional expressions, so we expected linear relations with outcomes. We tested the moderating role of gender in the relations between temperament and problem behaviors as well. Based on previous studies, we hypothesized that pure externalizing and co-occurring problems would share many childhood risk factors, including low effortful control, high impulsivity, high anger, high sadness, and low positive/high negative parental emotional expressivity, even after controlling for baseline symptoms. We hypothesized that pure internalizing would be predicted by high sadness, low impulsivity, low positive/high negative parental emotional expressivity, and possibly high anger. Based on prior research (e.g., Sentse et al., 2009), we expected interactions consistent with the dual-risk model, such that the effect of risky temperament would be stronger when parents displayed lower positive/higher negative emotional expressivity (Sameroff, 1983). We also expected that gender-specific pathways similar to those hypothesized for early adolescence might emerge in childhood.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a 6-year longitudinal study that oversampled children with behavior problems (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2004). Recruitment took place in schools and through newspaper ads and flyers placed at after-school programs and preschools. Prior to being selected for participation, parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for a total of 315 children (Achenbach, 1991a, 1991b). Following Achenbach (1991a, 1991b), T scores were computed, and children scoring 60 or above on either internalizing or externalizing were selected (N = 138). Then, children scoring below 60 on both internalizing and externalizing were matched on sex, parental education and occupation, age, and race to the former group and were included (N = 71). This resulted in a sample with a range of scores on the CBCL. Of the sample, 53.7% had a T score of ≥60 on internalizing, and 55.1% had a T score of ≥60 on externalizing problems (N = 214 at Time 1 [T1]). At least partial data were available for 193 children at Time 2, 185 at Time 3, and 168 at Time 4 (T4). The current study used data from T1 (4.5 to just turning 8 years old; M =73 months, SD =9 months) and T4 (10.5 to 14 years old). At T1, 84.6% of the sample was between the ages of 4.5 and 6 years old, and 15.4% of the sample was between the ages of 7 and 8 years old. Missing data techniques (see Analyses) included all participants who provided data on at least one study variable at T1 or T4 for the T1 to T4 prediction (N = 214) and all who provided data on at least one study variable at T4 for T4 concurrent prediction (N = 168). See Table 1 for sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variables | M (SD) | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|

| Time 1

| ||

| Age (months) | 73 (9) | — |

| Mother education | 14.11 (2.49) | — |

| Parent reported | ||

| Internalizing problems | 9.70 (6.62) | 0.83 |

| Externalizing problems | 14.84 (8.53) | 0.90 |

| Teacher reported | ||

| Internalizing problems | 4.16 (4.84) | 0.85 |

| Externalizing problems | 7.74 (9.40) | 0.94 |

| Parental positive expressivity subscale | 7.27 (0.98) | 0.85 |

| Parent | ||

| Positive affect puzzle box task | 1.66 (0.63) | 0.87 |

| Negative affect puzzle box task | 1.21 (0.31) | 0.82 |

| Positive affect free interaction | 1.80 (0.69) | 0.65 |

| Negative affect free interaction | 1.08 (0.25) | 0.62 |

| Parental emotional expressivity factor scores | 0.00 (0.25) | — |

| Parent reported | ||

| Sadness | 4.41 (0.76) | 0.64 |

| Anger | 4.81 (0.87) | 0.78 |

| Effortful control | 4.41 (0.74) | 0.91 |

| Impulsivity | 4.55 (0.84) | 0.81 |

|

| ||

| Time 4

| ||

| Parent reported | ||

| Sadness | 4.36 (0.80) | 0.79 |

| Anger | 4.57 (0.92) | 0.85 |

| Effortful control | 4.62 (0.75) | 0.90 |

| Impulsivity | 4.20 (0.91) | 0.83 |

| Externalizinga | 9.16 (6.91) | 0.88 |

| Internalizinga | 7.12 (6.33) | 0.86 |

| Teacher reported | ||

| Externalizinga | 5.33 (7.93) | 0.94 |

| Internalizinga | 4.25 (4.90) | 0.86 |

|

| ||

| %

| ||

| Gender | 55.1% Male | — |

| Race/ethnicity | 76.5% Caucasian | — |

| 12.2% Hispanic | ||

| 3.3% Black | ||

| 4.7% Native American | ||

| 0.5% Asian/Pacific Islander | ||

| 2.8% Other | ||

These Time 4 internalizing and externalizing outcomes are composites that were included here to describe the data. However, these composites were not used in any analyses; rather, individual Time 4 internalizing and externalizing items were used as indicators of a bifactor model.

Procedures

Primary caregivers (typically mother) completed questionnaires and behavioral tasks at a university laboratory. The other parent (if available) and teachers completed questionnaires at T1 and T4. Some participants who moved continued to participate via mail. Consent and assent were obtained at each assessment. Families received $25 at T1 and $30 at all other assessments.

Measures

Demographic variables

At T1, primary caregivers (at T1, 94.8% were mothers and 5.2% were fathers) reported on child’s age, sex, and mothers’ education (years; Table 1). Note mothers’, as opposed to fathers’, education was used as a covariate because mostly mothers participated in the laboratory task and reported on emotional expressivity and T4 early-adolescent symptoms.

Item overlap

We excluded temperament items that reflected psychopathology and vice versa to reduce confounding of measures. Briefly, 32 experts in temperament and child psychopathology rated the extent to which each item reflected temperament or psychopathology. Ratings were averaged to indicate the extent to which the item better reflected the other construct and these ratings were the basis for removal of items. See Eisenberg et al. (2005) for details. Note that deleting overlapping items from temperament scales did not affect results substantially.1

T1 and T4 problem behaviors

At T1, mothers and teachers rated (0 = not true, 1 = sometimes true, 2 = very true) children’s internalizing and externalizing using the CBCL. At T4, mothers (97.3%) or grandmothers (2.7%; referred to here as parents) and teachers rated children’s internalizing and externalizing using the CBCL. Due to overlap with temperament, we removed five internalizing and three externalizing items (for details, see Eisenberg et al., 2005) from T1 and T4. T1 reports were summed to form separate internalizing and externalizing composites using the same items used in the T4 bifactor model. T4 items were used to form item parcels (Nasser-Abu Alhija & Wisenbaker, 2006). See Data Analysis section for items used for T1 and T4 problem behaviors and Table 1 for αs and descriptives.

T1 and T4 temperament

At T1 and T4, primary caregivers (referred to here as parents; at T4 there were 95.2% mothers, 2.4% fathers, and 2.4% grandmothers) rated (1 =extremely untrue; 7 = extremely true) children on the attentional focusing, attentional shifting, inhibitory control, impulsivity, anger, and sadness subscales of the Child Behavior Questionnaire (Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001; attention shifting is from an early version only). Two attentional shifting, three sadness, and two anger items were removed due to overlap (for dropped items, see Eisenberg et al., 2005). For T1 and T4 measures, parent-reported attentional shifting, attentional focusing, and inhibitory control were averaged to form separate effortful control composites. Parent-reported impulsivity, sadness, and anger items were averaged to form separate subscales (see Table 1 for αs and descriptives).

T1 parental emotional expressivity

Parents’ emotional expressivity was measured with self-reports and observationally. Parents rated their positive emotional expressivity (1 = I rarely express these feelings; 9 = I frequently express these feelings) using the positive expressivity subscale of the Self-Expressiveness in the Family Questionnaire (Halberstadt et al., 1995; e.g., “Telling family members how happy you are”). Parents’ emotional expressivity was observed in behavioral tasks. In the first, an experimenter placed a puzzle in a box that had a clear Plexiglas back (to observe children’s hands) and a cloth on the front with sleeves for children’s arms. The parent sat on the clear side of the box and helped the child complete the puzzle verbally, but was not to do the puzzle for the child. Both were told that the child should finish the puzzle without looking and, if finished in 5 min, would receive an attractive prize.

During this time, parents’ positive emotions were coded every 30 s on a scale from 1 (low positive affect) to 5 (high positive affect) based on facial expressions (e.g., smiling) and laughing. Parents’ negative emotions were coded every 30 s on a scale of 1 (low negative affect) to 5 (high negative affect) based on facial expressions (e.g., frowning or biting lips) and negative tone of voice. The 10 positive and 10 negative affect codes (across the 5-min interaction) were averaged to form separate mean positive or negative affect scores. Coders were blind to hypotheses, and ratings took into account intensity and duration of affect. The interrater reliability, based on 52 families, was 0.83 for positive affect and 0.78 for negative affect. The second task was a 2-min free interaction where parent and child were left alone while the experimenter went to get something. Parents’ positive affect (e.g., smiling or positive comments) and negative affect (e.g., negative comments or irritation) were rated from 1 (none) to 5 (very frequent or intense) every 30 s. Codes were averaged across the 2-min period to create separate positive and negative affect composites. The interrater reliability based on 49 families was 0.77 for positive affect and 0.89 for negative affect. See Table 1 for αs and descriptives.

Parenting measures were reduced by conducting a one-factor confirmatory factor analysis in Mplus version 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2013) using maximum likelihood and full information maximum likelihood to estimate missing data. The following five indicators were used: parent-reported positive emotional expressivity and observed positive and negative affect during the puzzle task and free interaction. Model fit was good: χ2 (5) = 7.39, p = .19, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.05, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.95, standardized root mean square residual = 0.04. The standardized loadings were 0.30 for parent-reported positive emotionality expressivity, 0.60 for observed positive affect during the puzzle task, −0.34 for observed negative affect during the puzzle task, 0.49 for observed positive affect during the free interaction, and −0.35 for observed negative affect during the free interaction. All loadings were statistically significant (p < .05). Factor scores (which are manifest variables) of parental emotional expressivity were saved in Mplus and used in all subsequent analyses. We refer to this construct as “parental emotional expressivity,” with higher levels of the construct referring to high positive/low negative emotional expressivity.

Data analysis

We used Mplus version 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2013). Several steps were taken to fit the bifactor model. We tested four one-factor comfirmatory factor analyses for parent-reported externalizing and internalizing and teacher-reported externalizing and internalizing (using all items after removing overlap with temperament). Items that did not load at p ≤.05 or did not have a standardized loading above 0.30 were deleted2 to ensure that items used in bifactor models actually underlay the broader constructs of internalizing or externalizing, especially as items were to be parceled (see Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widamar, 2002). Several additional items had extremely low variability, such that no one responded very true and over 92% responded never regarding the particular behavior. We excluded those items as well.3

To reduce complexity, we created item parcels using the remaining 46 parent and 43 teacher items. Research suggests that more items per parcel tends to result in better solutions (Nasser-Abu Alhija & Wisenbaker, 2006). In addition, model convergence was facilitated by having more parcel indicators per factor (at least 17 parcels each for parent and teacher models). We attempted to maximize the number of parcels containing 3 items (with the rest containing 2 items) while retaining 17 parcels for each reporter. Items for each parcel were chosen at random. Parent externalizing items were partitioned into 9 parcels (7 of which contained 3 items and 2 of which contained 2 items), and parent internalizing items were partitioned into 8 parcels (5 of which contained 3 items and 3 of which contained 2 items). Teacher externalizing items were partitioned into 9 parcels (6 of which contained 3 items and 3 of which contained 2 items), and internalizing items into 8 parcels (3 of which contained 3 items and 5 of which contained 2 items.

Parent and teacher bifactor models were estimated simultaneously using maximum likelihood. All parent-reported parcels loaded onto a general, or co-occurring, problems factor; parent-reported externalizing parcels loaded onto a specific, or pure, externalizing factor; and parent-reported internalizing item parcels loaded onto a specific, or pure, internalizing factor. The same procedure was used for teacher item parcels. All factors were specified as orthogonal except a correlation was allowed between parent and teacher pure externalizing, parent and teacher pure internalizing, and parent and teacher co-occurring problems factors. This is because different raters’ assessments of the same construct were not expected to be orthogonal; rather, only pure internalizing, pure externalizing, and co-occurring problems were specified to be orthogonal (see Keiley et al., 2003). Modification indices isolated sources of model misfit. Goodness of fit was determined using chi-square test of model fit and the following cutoffs: CFI ≥0.95 and RMSEA ≤0.06. Predictors were mean-centered. Interactions were probed as simple slopes at 1 standard deviation above (referred to as high) and below (referred to as low) the mean (Aiken & West, 1991; see Results); mean levels are not presented to reduce the complexity of data presentation (this information available upon request).

Results

Zero-order correlations

Correlations between study predictors and outcome parcels were not included because there were 89 item parcels. We examined zero-order correlations of T4 composite reports of internalizing and externalizing instead (although note that T4 problem behavior composite scores were not used in main analyses). Higher parental emotional expressivity at T1 was significantly correlated with most T1 temperament measures and with both reports of T1 and T4 externalizing (see Table 2). However, T1 parental emotional expressivity was significantly correlated only with lower effortful control at T4. Within-wave, higher effortful control was significantly or marginally correlated with lower anger, impulsivity, and sadness, and higher anger correlated with higher impulsivity. Sadness and impulsivity were generally not correlated. All correlations between the same temperament construct at T1 and T4 were significant. Note the substantial correlations between T1 externalizing and both T1 anger and T1 low effortful control. Both reports of T4 externalizing were significantly or marginally correlated with T1 and T4 higher anger, lower effortful control, and higher impulsivity. Parent-reported internalizing at T4 was significantly or marginally correlated with T1 and T4 higher anger, sadness, and lower effortful control. Teacher-reported internalizing at T4 was not correlated with any measures of temperament. Female gender was related to higher effortful control for both waves, and somewhat with lower impulsivity (all correlations were at least near significant).

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations among manifest study predictors

| Gender | T1 Mother Educa. |

T1 Age |

T1 Parent. |

T1 Anger |

T1 Sad. |

T1 EC |

T1 Impuls. |

T4 EC |

T4 Anger |

T4 Sad. |

T4 Impuls. |

T1 EXT (P) |

T1 INT (P) |

T1 EXT (T) |

T1 INT (T) |

T4 EXT (P) |

T4 INT (P) |

T4 EXT (T) |

T4 INT (T) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | — | −.01 | −.10 | −.09 | .09 | −.15* | −.22** | .13† | −.24** | .004 | −.08 | .19* | .16* | .05 | .23** | −.003 | .05 | −.04 | .25** | .16† |

| T1 mother educa. | — | −.001 | .15* | −.06 | −.09 | .02 | −.01 | .02 | .01 | −.06 | −.09 | −.11 | −.13 | −.01 | −.12 | −.23* | −.08 | −.23** | −.23** | |

| T1 age | — | −.08 | −.14* | .01 | .16* | −.19** | .04 | .02 | .06 | −.09 | −.10 | .15* | .06 | .04 | .01 | .11 | −.10 | .02 | ||

| T1 parent. | — | −.03 | .15* | .20** | −.16* | .25** | −.11 | .01 | −.14† | −.19** | .08 | −.26** | −.08 | −.23** | −.10 | −.22** | −.14 | |||

| T1 anger | — | .38** | −.54** | .29** | −.41** | .59** | .26** | .26** | .60** | .36** | .32** | .20** | .56** | .29** | .15† | .02 | ||||

| T1 sad. | — | −.13† | −.12† | .003 | .27** | .55** | −.07 | .09 | .37** | .04 | .13† | .07 | .34** | −.12 | −.12 | |||||

| T1 EC | — | −.47** | .69** | −.44** | −.23** | −.50** | −.61** | −.29** | −.45** | −.20** | −.46** | −.15† | −.28** | −.02 | ||||||

| T1 impuls. | — | −.42** | .15† | −.04 | .66** | .46** | −.05 | .40** | .08 | .35** | −.11 | .34** | .13 | |||||||

| T4 EC | — | −.52** | −.25** | −.53** | −.50** | −.14 | −.38** | −.16* | −.55** | −.26** | −.31** | −.10 | ||||||||

| T4 anger | — | .47** | .25** | .47** | .23** | .34** | .23** | .61** | .35** | .17* | .06 | |||||||||

| T4 sad. | — | .04 | .12 | .35** | .04 | .15† | .23** | .46** | −.04 | .06 | ||||||||||

| T4 impuls. | — | .46** | .05 | .31** | .07 | .45** | −.02 | .27** | .03 | |||||||||||

| T1 EXT (P) | — | .54** | .48** | .23** | .62** | .28** | .30** | .06 | ||||||||||||

| T1 INT (P) | — | .22** | .18* | .26** | .50** | .03 | −.02 | |||||||||||||

| T1 EXT (T) | — | .48** | .34** | .06 | .38** | .15 | ||||||||||||||

| T1 INT (T) | — | .10 | .07 | −.06 | .03 | |||||||||||||||

| T4 EXT (P) | — | .35** | .35** | .17† | ||||||||||||||||

| T4 INT (P) | — | −.14† | −.04 | |||||||||||||||||

| T4 EXT (T) | — | .47** | ||||||||||||||||||

| T4 INT (T) | . | — |

Note: T1, Time 1; T4, Time 4; EXT, externalizing; INT, internalizing; Parent., parental emotional expressivity; Sad, sadness; EC, effortful control; Impuls., impulsivity; (P), parent report; (T), teacher report; gender, 0 = female, 1 = male. T4 composites of INT and EXT are shown here, which are not used in any main analyses.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Bifactor model of early adolescent problem behaviors

After estimating the proposed bifactor model, modification indices indicated that the addition of 14 correlations between the error terms of items within the same reporter would improve model fit, and these were mostly among parcels within the same construct. The need for these specifications is likely due to similar item content or facets within internalizing and externalizing that we did not model. After adding these, model fit was acceptable: χ2 (477) = 657.49, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.05, and CFI = 0.94. Standardized loadings ranged from 0.16 to 0.89 and all ps < .09. Some items had a factor loading that would be considered less than “substantial” on one factor (e.g., <0.30), but these items always loaded above 0.30 on the other factor (e.g., pure vs. co-occurring) and the R2 for each item were generally quite high, all above .30. These model characteristics are similar to those from a recent study that examined a bifactor model of adolescent internalizing and externalizing co-occurrence (Colder et al., 2013). Parent- and teacher-reported pure externalizing factors were significantly correlated (r =.29, p =.04), but co-occurring problems (r = .08, ns) and pure internalizing (r = .07, ns) were not.

Structural equation models

We tested prediction of both parent- and teacher-reported problem behaviors by parent-reported temperament. For models examining prediction from both T1 and T4 variables, we tested main effect analyses, without interactions, to compare with previous work and to gain a clearer understanding of their concurrent and longitudinal prediction. Thus, we tested the main effect of each parent-reported T4 temperament characteristic in a separate model on T4 problem behaviors while controlling for child age, mothers’ education, and gender. Next, we tested interactions between T4 temperament and gender by entering their cross-product. Parenting interactions were not tested for T4 concurrent predictions because we did not assess parenting at this wave. As noted above, we entered each temperament characteristic in separate models because we were not interested in unique prediction by each temperament characteristic over and above the other temperament characteristics. Furthermore, some of these aspects of temperament load on the same higher order facet of temperament (e.g., negative emotionality) and some aspects of temperament were fairly highly related to one another in our study (see Table 2). Thus, entering all temperament predictors simultaneously would make results more difficult to interpret due to statistical and conceptual overlap. Moreover, doing so could also increase the likelihood that the temperament characteristic that is least associated with the other temperament characteristics would have the clearest links with the outcome, even if it was less associated with the outcome initially.

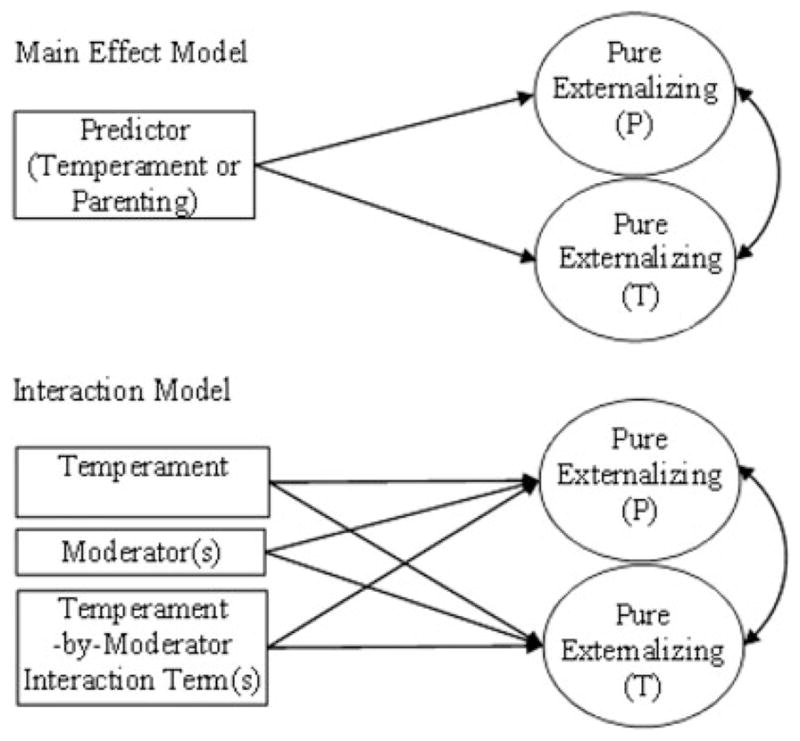

Note also that separate models were run for each outcome as well. That is, paths were estimated from the predictors and covariates mentioned above to parent- and teacher-reported pure externalizing factors only, and not to parent- or teacher-reported pure internalizing or co-occurring problems (and the same for pure internalizing and co-occurring problems). However, in all cases, the entire measurement model of the outcomes was still estimated. If different outcome factors (e.g., pure vs. co-occurring) were allowed to be predicted in the same model all at once (rather than separately), the outcome factors would be correlated with one another through the predictor variables. Because an important aspect of the bifactor model is that the factors are orthogonal, it is necessary to estimate predictor and covariate effects to one outcome at a time (see Keiley et al., 2003). See Figure 1 for conceptual models of analyses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of analyses with one outcome factor. Paths from gender, mothers’ education, and age to outcomes were estimated in all models. Main effect models were estimated using predictors of Time 1 (T1) and Time 4 (T4) effortful control, anger, sadness, and impulsivity and T1 parental emotional expressivity (predictors were each entered in models separately). T1 interaction models built on T1 temperament main effect models by entering parenting (gender already included in all models), a Temperament × Parenting, and a Temperament × Gender cross-product. T4 interaction models built on T4 temperament main effect models by entering a Temperament × Gender cross-product (gender already included in all models). Main effect and interaction models are repeated using all possible combinations of predictors and T4 outcome factors (pure externalizing, pure internalizing, and co-occurring problems). Note that the entire bifactor (i.e., measurement) model is estimated in all main effect and interaction models, but the other outcome factors are not shown here for ease of presentation. Correlations among exogenous variables were not included for ease of presentation.

To test longitudinal prediction of T4 problem behaviors, we tested main effects of each parent-reported T1 temperament characteristic and of parental emotional expressivity (each tested in a separate model) on each of the T4 factors, controlling for child age, gender, mothers’ education, and T1 symptoms (T1 internalizing when predicting T4 pure internalizing, T1 externalizing when predicting T4 pure externalizing, and both T1 internalizing and externalizing when predicting T4 co-occurring problems, all within-reporter). Next, we tested interactions by entering the following as predictors: T1 temperament (each in a separate model), parenting, gender, T1 age, mothers’ education, T1 corresponding problem behaviors (same as above), T1 Temperament × Pa-rental Expressivity, and T1 Temperament × Gender (cross-products) on T4 symptoms. T1 symptoms were included to predict change in symptoms from childhood to early adolescence over 6 years. Nonsignificant interactions were trimmed. No three- or four-way interactions were tested because our sample size had limited power to detect such interactions.

In total, there were 114 tests. Note that due to the large number of analyses, we do not report lone marginal findings for main effects if a finding for a given aspect of temperament and a given outcome (e.g., effortful control predicting pure externalizing) was not replicated at least at the marginal level for the other reporter of adjustment, for at least one sex or level of parental expressivity. We also do not report marginal interactions in the text.

Pure externalizing problems

Main and interactive effects of T4 variables on T4 pure externalizing

Lower effortful control predicted higher parent- and teacher-reported pure externalizing (Table 3; one reporter of predictors × two reporters of outcomes). Higher impulsivity predicted higher parent- and teacher-reported pure externalizing, and a significant interaction revealed that higher impulsivity predicted parent-reported pure externalizing more strongly for boys than for girls (but significant for both sexes). Higher anger predicted higher parent-reported pure externalizing, and this effect was stronger for boys than for girls (significant for both sexes). Lower sadness predicted higher parent-reported pure externalizing problems.

Table 3.

Main and interactive effects of T4 temperament on T4 pure versus co-occurring symptomatology

| Predictors | T4 Pure EXT Parent

|

T4 Pure EXT Teacher

|

T4 Co-occurring EXT/INT Parent

|

T4 Co-occurring EXT/INT Teacher

|

T4 Pure INT Parent

|

T4 Pure INT Teacher

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Main: T4 EC (P) | −0.61 (0.06)** | −0.24 (0.09)* | −0.62 (0.06)** | −0.26 (0.08)* | −0.08 (0.11) | 0.04 (0.10) |

| EC ×GEN (P) | [×] | [1.02 (0.57)]†, for girls: −0.43 (0.14)* | [×] | [×] | [×] | [×] |

| Main: T4 IMP (P) | 0.59 (0.07)** | 0.17 (0.09)* | −0.01 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.08)† | −0.26 (0.10)* | −0.02 (0.09) |

| IMP ×GEN (P) | [1.23 (0.37)]**, stronger for boys: 0.83 (0.10)**, than girls: 0.34 (0.11)** | [×] | [1.00 (0.39)]*, for boys: 0.58 (0.15)** | [1.09 (0.39)]*, for boys: 0.439 (0.12)** | [×] | [×] |

| Main: T4 Anger (P) | 0.65 (0.06)** | 0.11 (0.09) | 0.68 (0.05)** | 0.17 (0.08)* | 0.07 (0.11) | 0.01 (0.09) |

| ANG ×GEN (P) | [0.96 (0.36)]*, stronger for boys: 0.84 (0.08)**, than girls: 0.47 (0.09)** | [×] | [×] | [0.84 (0.41)]*, for boys: 0.34 (0.11)* | [1.08 (0.50)]*, for girls: 0.25 (0.14)† | [×] |

| Main: T4 Sadness (P) | −0.26 (0.12)* | −0.13 (0.09) | 0.46 (0.07)** | 0.02 (0.08) | 0.49 (0.10)** | 0.08 (0.09) |

Note: N = 168. The results from the main effects models that controlled for Time 4 (T4) age, mother education, and gender. Bold effect values are marginally or statistically significant and grayed effects are non-significant. Coefficients in brackets [] refer to the interaction coefficient. Standardized coefficients are reported. For interaction effects, coefficients refer to the effect of T4 temperament on T4 symptoms for boys or for girls. If a simple slope was nonsignificant, it was not reported for brevity. EXT, externalizing; INT, internalizing; EC, effortful control; (P), parent reported; GEN, gender; IMP, impulsivity; ANG, anger.

p≤.10.

p ≤.05.

p ≤.001.

[×], an interaction term that was p > .10 and was trimmed from the final model.

Main and interactive effects of T1 variables on T4 pure externalizing, when controlling for T1 externalizing

After controlling for T1 externalizing, lower parental emotional expressivity predicted higher teacher-reported pure externalizing (and marginally predicted parent-reported pure externalizing; see bottom left of Table 4). Lower effortful control near significantly predicted higher parent-reported pure externalizing, and a significant interaction indicated that this effect was only significant at low levels of parental emotional expressivity. Effortful control did not have a significant main effect on teacher-reported pure externalizing, but effortful control did significantly predict pure externalizing only for girls and only at low parental emotional expressivity. Higher impulsivity predicted higher parent-reported pure externalizing, and this effect was only significant for boys and at low parental emotional expressivity. Higher impulsivity also near significantly predicted higher teacher-reported pure externalizing, and a significant interaction indicated that this effect was only significant for girls. Higher anger predicted higher parent-reported pure externalizing, and this effect was only significant at low parental expressivity. Sadness predicted pure externalizing in only one model and is not discussed further.

Table 4.

Main and interactive effects of T1 temperament and parenting on T4 pure versus co-occurring symptomatology, controlling for T1 analogous adjustment

| Predictors | T4 Pure EXT Parent

|

T4 Pure EXT Teacher

|

T4 Co-occurring EXT/INT Parent

|

T4 Co-occurring EXT/INT Teacher

|

T4 Pure INT Parent

|

T4 Pure INT Teacher

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Main: T1 EC (P) | −0.17 (0.09)† | −0.07 (0.10) | −0.17 (0.09)* | −0.10 (0.09) | 0.17 (0.09)† | 0.17 (0.10)† |

| EC ×GEN (P) | [×] | [*], for girls: −0.31* | [×] | [*], for boys: −0.21** | [×] | [×] |

| EC ×PAR (P) | [*], low PAR: −0.29* | [*], low PAR: −0.25* | [*], low PAR: −0.28* | [×] | [×] | [×] |

| Main: T1 IMP (P) | 0.21 (0.08)* | 0.15 (0.09)† | −0.11 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.08)† | −0.25 (0.09)* | 0.04 (0.09) |

| IMP ×GEN (P) | [*], for boys: 0.38** | [*], for girls: 0.29* | [×] | [**], for boys: 0.41** | [×] | [×] |

| IMP ×PAR (P) | [*], low PAR: 0.38** | [×] | [×] | [×] | a[†], low PAR: −0.41** | [×] |

| Main: T1 Anger (P) | 0.27 (0.09)* | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.35 (0.08)** | 0.02 (0.08) | −0.17 (0.12) | −0.08 (0.09) |

| ANG ×GEN (P) | [×] | [×] | [×] | a[*], for boys: 0.17, ns; for girls: −0.11, ns | [*], for boys: −0.30* | [×] |

| ANG ×PAR (P) | [*], low PAR: 0.47** | [×] | [*], stronger at low: 0.52** than high PAR: 0.23* | [×] | [×] | [×] |

| Main: T1 SAD (P) | −0.12 (0.08) | a−0.14 (0.08)† | 0.19 (0.08)* | −0.08 (0.08) | a0.16 (0.09)† | −0.10 (0.09) |

| SAD ×GEN (P) | [×] | [†],a for girls: −0.23* | [×] | [×] | [×] | [×] |

| Main: T1 Parenting | −0.12 (0.07)† | −0.17 (0.09)* | −0.14 (0.07)* | −0.03 (0.08) | −0.13 (0.09) | −0.05 (0.09) |

Note: N = 214. The results from main effects models that controlled for Time 1 (T1) age, gender, mother education, and T1 analogous adjustment. Bold effect values are marginally or statistically significant and grayed effects are nonsignificant. The symbol in brackets [/] refers to a p value of the interaction effect. Standardized coefficients reported. For interaction effects, coefficients refer to the effect of T1 temperament on Time 4 (T4) symptoms at a certain level of the moderator. If a simple slope was nonsignificant, it was not reported for brevity. Interaction terms probed at low (1 SD below mean) and high (1 SD above mean) levels of parental emotional expressivity. EXT, Externalizing; INT, internalizing; EC, effortful control; (P), parent reported; GEN, gender; IMP, impulsivity; ANG, anger; PAR, parenting; SAD, sadness.

Not described in the text (see Results section for more details).

p ≤.10.

p ≤.05.

p ≤.001.

ns, p > .10. [×], an interaction term that was p > .10 and was trimmed from the final model.

Co-occurring problems

Main and interactive effects of T4 variables on T4 co-occurring problems

Lower effortful control predicted higher parent- and teacher-reported co-occurring problems (Table 3). Higher impulsivity predicted higher parent- and teacher-reported co-occurring problems, but only for boys. Higher anger predicted higher parent- and teacher-reported co-occurring problems, and a significant interaction indicated that higher anger significantly predicted higher teacher-reported co-occurring problems only for boys. Higher sadness predicted parent-reported co-occurring problems.

Main and interactive effects of T1 variables on T4 co-occurring problems when controlling for T1 externalizing and internalizing

After controlling for T1 symptoms, lower parental emotional expressivity predicted higher parent-reported co-occurring problems (Table 4). Lower effortful control predicted higher parent-reported co-occurring problems, and this effect was significant only at low parental positive expressivity. Lower effortful control also predicted higher teacher-reported co-occurring problems for boys only. Impulsivity did not have more than one near significant main effect and is not discussed further. Higher anger predicted higher parent-reported co-occurring problems, and this effect was stronger at low, than at high, parental expressivity (although significant for both). Higher sadness predicted higher parent-reported co-occurring problems.

Pure internalizing problems

Main and interactive effects of T4 variables on T4 pure internalizing

All significant effects were for parent-reported pure internalizing problems. Effortful control did not significantly predict pure internalizing; in contrast, lower impulsivity predicted higher pure internalizing (see Table 3). In addition, higher anger was associated with higher pure internalizing, but the relation held primarily for girls. Higher sadness predicted higher pure internalizing.

Main and interactive effects of T1 variables on T4 pure internalizing when controlling for T1 internalizing

All significant effects were for parent-reported pure internalizing (Table 4). Parental emotional expressivity had no main effects on pure internalizing. Lower impulsivity predicted higher pure internalizing. Lower anger predicted higher pure internalizing for boys only.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine the longitudinal (over 6 years) and concurrent effects of temperament on early adolescent pure and co-occurring externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors during an important developmental period when these problem behaviors increase and temperamental correlates might change (Cohen et al., 1993). We also examined parental emotional expressivity and gender as moderators of these relations. We used a bifactor model to characterize pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems, which resulted in continuous and error-free latent factors. This approach circumvents some limitations of categorical approaches, such as the potential for incorrect categorization and lack of concordance with notions that psychological problems are continuous. In discussing results, we focus on replicated findings and patterns observed in the data.

We found that early-adolescent low effortful control and high impulsivity were concurrently associated with parent-and teacher-reported pure externalizing and co-occurring problems. Thus, individuals with pure externalizing and co-occurring problems were viewed by adults as lacking in self-regulation and high in impulsive responding, in line with previous studies (Oldehinkel et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2015), including those in the same sample at younger ages (Eisenberg et al., 2001, 2005, 2007, 2009). However, prediction by impulsivity was somewhat less evident for co-occurring problems than for pure externalizing. In particular, high impulsivity only predicted co-occurring problems for boys, whereas high impulsivity predicted pure externalizing across both genders. The more robust relation between impulsivity and pure externalizing is consistent with results reported 2 years earlier in the same sample (Eisenberg et al., 2009) and another study that found that pure externalizers had greater high-intensity pleasure than those with co-occurring problems (Oldehinkel et al., 2004). Researchers suggested that the more inhibited style of responding associated with internalizing might somewhat buffer children with co-occurring problems from the more problematic impulsive tendencies associated with externalizing (Eisenberg et al., 2009). Our findings extend this work to suggest that co-occurring internalizing problems might reduce the likelihood of problematic tendencies associated with externalizing, like impulsivity, primarily for girls.

More pronounced differences emerged when examining T1 temperamental antecedents of pure externalizing and co-occurring problems while controlling for T1 analogous adjustment. Namely, there was modest evidence that both low effortful control and high impulsivity predicted changes in pure externalizing for certain subgroups (see later sections). That effortful control and impulsivity predicted change in pure externalizing over 6 years indicates that lack of voluntary self-regulation and increased reflexive tendencies toward undercontrol in childhood portend pure externalizing. These analyses also showed that low effortful control predicted change in co-occurring problems over 6 years (but only for certain subgroups, see later sections). However, there was little evidence that higher impulsivity predicted change in co-occurring problems. Because impulsivity in childhood tends to be negatively related to internalizing and positively related to externalizing symptoms (e.g., Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2015), perhaps the effect of impulsivity on change in co-occurring symptoms is minimal. In addition, if co-occurring problems develop because internalizing causes externalizing and vice versa, then both low and high levels of childhood impulsivity could portend co-occurring problems and wash out effects of impulsivity.

Somewhat unexpectedly, we did not find consistent evidence that childhood effortful control prospectively, or early adolescent effortful control concurrently, predicted pure internalizing. Perhaps this is because components of effortful control (e.g., inhibitory vs. attentional control) have different effects on internalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2004) or because any relations for effortful control are not unique to pure internalizing. In contrast, lower childhood and early adolescent impulsivity predicted higher parent-, but not teacher-, reported pure internalizing, similar to several previous studies (Keiley et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2015). Our results are also similar to findings from several years prior in the same sample, which suggested that less voluntary (e.g., behavioral inhibition and low impulsivity), rather than voluntary (e.g., effortful), control is the most important predictor of pure internalizing (Eisenberg et al., 2009). Note that because the findings for internalizing were only for parent-reported internalizing, this association might only be present in the home context or could be due to reporter bias. Nonetheless, one interpretation of this finding is that children low in impulsivity, who lack spontaneity and flexibility, might cope less adaptively in novel situations or with negative emotions and might be perceived as dull and overly rigid by peers. These children may also have low positive affect due to low BAS (Gray, 1990). These characteristics may set children on a trajectory toward pure internalizing in early adolescence. Furthermore, when these children became early adolescents, they were still viewed as constrained and overly inhibited. Taken together, our findings are also consistent with previous behavior genetic studies suggesting that the propensity for adventurousness and behavioral disinhibition (i.e., impulsivity) may be a broad-band specific feature distinguishing externalizing from internalizing (e.g., Rhee, Lahey, & Waldman, 2014).

Childhood anger prospectively predicted only parent-reported pure externalizing and co-occurring problems. This suggests that children’s anger may be longitudinally predictive of change in both pure externalizing and co-occurring problems, but this may only apply in the home context or may be due to reporter bias. Similarly, early-adolescent anger only predicted parent-reported pure externalizing, which may be interpreted similarly to the childhood anger findings. However, early-adolescent anger predicted both parent- and teacher-reported co-occurring problems. Thus, early-adolescent co-occurring problems show the clearest associations with concurrent levels of anger, which is the same as findings from years prior in the same sample (Eisenberg et al., 2009). Perhaps early adolescents with co-occurring problems are perceived as angrier and their acting out behaviors are due to feelings of anger. This finding is also consistent with another study that showed that infants’ irritability predicted only co-occurring, and not pure, problem behaviors (Keiley et al., 2003). Taken together, results suggest that anger and negative emotionality may underlie the overlap between externalizing and internalizing problems, which is also supported by previous behavior genetic work (e.g., Rhee et al., 2014).

Childhood and early-adolescent anger were infrequently associated with pure internalizing. Previous findings with the same sample at younger ages suggested that anger might predict pure internalizing more strongly with age (Eisenberg et al., 2005), perhaps because individuals with internalizing pathology tend to have increasing problems with social relationships as they progress through school (Rubin, Hastings, Chen, Stewart, & McNichol, 1998). This did not appear to be the case in early adolescence, but perhaps it is necessary to assess problem behaviors at even older ages as these problems continue to intensify. Another possibility is that covarying out co-occurrence with externalizing problems using the bifactor approach eliminated the previously observed relation between anger and pure internalizing found when using traditional cutoffs (e.g., Oldehinkel et al., 2004). Finally, if children with pure internalizing problems become progressively angrier over development, it is possible that by early adolescence these children have developed co-occurring problems, accounting for the lack of association between anger and pure internalizing at this age.

Sadness in childhood was not a robust prospective predictor of early adolescent problem behaviors, with only one significant effect of higher childhood sadness on greater parent-reported co-occurring problems. The results suggest that sadness may not necessarily precede pure externalizing or internalizing problems. They also provide modest evidence that higher sadness may predict change in co-occurring problems over 6 years in the home context. This finding is somewhat consistent with previous work suggesting a stronger association of general negative emotionality with co-occurring than with pure problem behaviors (Keiley et al., 2003; Rhee et al., 2014). However, concurrent relations among early adolescent sadness and problem behaviors were somewhat more consistent, although only for parent-reported problem behaviors. Specifically, parent-reported co-occurring problems and pure internalizing were associated with higher sadness in early adolescence, in line with findings from 2 years prior (Eisenberg et al., 2009). High sadness might be associated with co-occurring problems if individuals have not developed appropriate ways of dealing with negative emotions (e.g., hitting) or if these individuals experience sadness as a result of social and academic problems accompanying externalizing behaviors. High sadness might be associated with pure internalizing problems because inhibition and withdrawal often have negative consequences or because it reflects proneness to depression.

Unexpectedly, lower early-adolescent sadness predicted higher parent-reported pure externalizing. That children’s lower sadness also marginally and prospectively predicted higher teacher-reported pure externalizing suggests that this finding may not be spurious (see Table 4). In light of this, it is worth noting that there exists a subgroup of children with conduct problems who also have callous–unemotional traits. They have a more stable and aggressive trajectory of antisocial behaviors, deficits in detecting sadness and fear (Blair, Peschardt, Budhani, Mitchell, & Pine, 2006), and deficits in experiencing sadness, especially in response to others’ distress (Pardini & Byrd, 2012). Perhaps associations between low sadness and pure externalizing are driven by those with callous–unemotional traits.

A novel contribution of this study was our examination of main and interactive effects of childhood parental emotional expressivity on pure and co-occurring problems. Low parental positive versus negative expressivity in childhood predicted change in both reports of pure externalizing over 6 years. There was also evidence that low parental expressivity in childhood predicted change in parent-reported co-occurring problems. In contrast, parents’ emotional expressivity did not predict pure internalizing. The exact same pattern was found by Keiley et al. (2003), where harsh parenting was related to mother- and teacher-reported pure externalizing problems, only related to mother-reported co-occurring problems, and was not related to pure internalizing problems. Thus, parents’ more negative, and less positive, emotional expressions with their child are more strongly linked with change in pure externalizing than with co-occurring problems or pure internalizing, at least in regard to main effects.

Parental expressivity and effortful control also interacted to predict both parent- and teacher-reported pure externalizing. The interaction was consistent with the dual-risk model and followed a “vulnerable and reactive” pattern that has also been observed in previous studies (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Sameroff, 1983; Sentse et al., 2009). Specifically, low effortful control in childhood predicted change in early adolescent pure externalizing only when parents were expressive of high negative/low positive emotions. Findings illustrate the important role of children’s environment in buffering the impact of temperament on later problem behaviors. Thus, prevention programs might focus on teaching parents to modulate emotional expressions, because they may protect high-risk children from developing problem behaviors. In addition, the results raise the interesting possibility that a specific risk factor for pure externalizing is the combination of children’s deficient self-regulation and parents’ negative emotional expressivity. Perhaps children who are less able to regulate their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors model their parents’ hostile or angry emotional expressions in disruptive and inappropriate ways, leading to the development of pure externalizing problems.

Parental expressivity also interacted with anger or impulsivity to predict parent-reported pure externalizing and with effortful control or anger to predict parent-reported co-occurring problems. The interactions were such that higher anger or impulsivity predicted pure externalizing, and lower effortful control or higher anger predicted co-occurring problems, only or more strongly when parental expressivity was more negative/low positive. Because these effects were only found in within-parent models, it is difficult to conclude whether they are more likely observed in the home or due to reporter bias.

We found the most evidence for parental expressivity interactions with effortful control, followed by interactions with anger and impulsivity, when predicting pure externalizing. Previous research suggests that effortful control becomes a stronger unique predictor of externalizing problems with age, over and above other aspects of temperament (Eisenberg et al., 2004; Valiente et al., 2003). At this older age, effortful control might similarly emerge as a stronger predictor of externalizing problems in the context of interactions. Due to the modulating role of effortful control over impulsivity or anger (Eisenberg et al., 2009), parenting interactions observed with anger or impulsivity might be indirect, operating through the effect of parental expressivity on effortful control.

Parental emotional expressivity marginally significantly interacted with impulsivity to predict pure internalizing problems. This effect was found in only one model and could be spurious. That parental emotional expressivity did not have significant main (as described above) or interactive effects on pure internalizing suggests that this parental style is not as important in the development of pure internalizing (either directly or in combination with risky temperamental traits) when compared to pure externalizing and co-occurring problems. Previously, researchers found associations between parental emotional expressivity and internalizing that appeared to operate through low effortful control (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Valiente et al., 2006). Perhaps differences between these previous studies and the current results are due to our accounting for the co-occurrence of externalizing with internalizing and examining variance that was unique to internalizing items. Findings suggest that environmental correlates of pure internalizing might be quite different from those for internalizing when externalizing co-occurrence has not been considered. It is likely that other aspects of parenting are important in the development of pure internalizing, which is an interesting avenue for future research.

We found that the relation of high impulsivity to co-occurring problems was stronger for boys than for girls, and this was especially robust when examining concurrent T4 relations. We had expected that this gender difference would also apply to pure externalizing, but it did not. The obtained relation was not due to the increased variability of impulsivity in boys compared to girls. Girls had higher variability in impulsivity than boys at both waves, although these differences were not significant at T1 or T4. Thus, this finding might suggest different etiological mechanisms underlying the development of co-occurring problems for boys versus girls. It is unclear from the current study how girls with co-occurring problems were viewed by adults, which might be explored in future research.

Another robust gender pattern observed was that relations between multiple aspects of T1 or T4 temperament and teacher-reported pure externalizing only held or were stronger for girls, whereas relations between multiple aspects of temperament and teacher-reported co-occurring problems only held for boys. Due to externalizing problems being more stereotypically masculine, perhaps teachers are especially aware of pure externalizing behaviors enacted by girls and tend to view girls who display pure externalizing problems as particularly unregulated and impulsive. However, perhaps girls with co-occurring internalizing problems, due to inhibition or social withdrawal, do not seem especially unregulated, impulsive, or angry to teachers. Conversely, because internalizing problems are stereotypically more gender-typical for girls, boys who display internalizing along with externalizing problems may be especially salient to teachers.

The current study has several limitations. Three- and four-way interactions were not tested due to probable lack of power. Adolescents are informative reporters of their own internalizing problems, so it would have been beneficial to include child-report measures. We did not measure parental expressivity in early adolescence and could not test its moderation of early-adolescent temperament. Future research might consider additional aspects of temperament that may protect against problem behaviors, with established importance, like exuberance, or that might have stronger links to internalizing problems, such as low positive emotionality. This study also has strengths that add to the existing literature. To our knowledge, few researchers have examined both longitudinal and concurrent temperamental risk factors for early adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems while considering co-occurrence using a bifactor model. Furthermore, few researchers, to our knowledge, have examined whether these relations are moderated by parenting or gender in this context. Using a bifactor model to characterize co-occurrence might have facilitated the detection of more subtle patterns of results due to increases in power associated with using continuous measures and the possibility for incorrect categorization when using categorical measures. Using parents’ and teachers’ reports allowed us to test whether effects were robust across contexts and ameliorated concerns that results are due to reporter bias for some findings.