Abstract

It is important to understand the acculturation process of ethnic minority youth: To which cultures do they orient, and how do their cultural orientations develop? The present study tests a tridimensional acculturation model in Chinese American families and examines a potential mechanism through which parental cultural orientations may relate to adolescent cultural orientations. Participants were 350 Chinese American adolescents (Mage =17.04, 58% female) and their parents in Northern California. Results support the tridimensional acculturation model by demonstrating moderate associations among Chinese American orientation, Chinese orientation, and American orientation; our findings also point to a unique effect of parental Chinese American orientation on parental bicultural socialization beliefs. Most importantly, we identified an indirect pathway from parental to adolescents’ Chinese American orientation through adolescents’ internalization of parental bicultural socialization beliefs.

Keywords: tridimensional acculturation, Chinese American, intergenerational transmission, bicultural socialization, adolescents

Introduction

It is important to understand the acculturation process of ethnic minority youth: To which cultures do they orient, and how do their cultural orientations develop? For the first question, recently, researchers have proposed a tridimensional model of acculturation (Ferguson, Iturbide, & Gordon, 2014; Flannery, Reise, & Yu, 2001). It suggests that, in addition to the ethnic culture and the mainstream culture present in the bidimensional model, ethnic minorities can orient to a third culture, one that integrates features of, but is distinct from, both the ethnic culture and the mainstream culture. While extant studies on Chinese Americans’ acculturation have relied on the bidimensional model of acculturation to study participants’ Chinese orientation and American orientation (Chen et al., 2014; Kim, Wang, Chen, Shen, & Hou, 2014), it is important to consider their Chinese American orientation also, so as to capture the essence of what it is like to live in the U.S. as an ethnic minority. For the second question, in the development of cultural orientations among adolescents, intergenerational transmission of cultural orientations through bicultural socialization may play an important role.

A few prior studies have demonstrated intergenerational transmission of ethnic cultures from parents to adolescents through ethnic socialization (Knight et al., 2011; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009). Recent studies have indicated that ethnic minority parents in the U.S. (e.g., Chinese American parents) socialize their children not only toward the ethnic culture but also toward the mainstream American culture; they hold bicultural socialization beliefs, believing that it is important for their children to adopt both cultures, ethnic and American. For example, Chinese American parents may want their children to be “American” but still retain parts of Chinese culture (Cheah, Leung, & Zhou, 2013; John & Montgomery, 2012; Lieber, Nihira, & Mink, 2004; Uttal, 2011). Parents’ beliefs about the importance of adopting both cultures may be internalized to form adolescents’ own bicultural socialization beliefs, thus linking parents’ and adolescents’ cultural orientations. Therefore, by examining parents’ and adolescents’ orientations toward Chinese, American, and Chinese American cultures simultaneously, the current study aims to test the tridimensional acculturation model and examine one potential mechanism through which adolescents develop their cultural orientations: intergenerational transmission of cultural orientations through bicultural socialization beliefs.

Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Orientations

Few studies have investigated the antecedents of adolescent cultural orientations. It is important to do so because cultural orientations (e.g., Chinese orientation and American orientation) have often been associated with adolescent outcomes, such as socioemotional well-being and academic performance (Chen et al., 2014; Kim, Shen, Huang, Wang, & Orozco-Lapray, 2014; Kim, Wang, et al., 2014; Lim, Yeh, Liang, Lau, & McCabe, 2008 ). As adolescence is a key developmental period for identity and ethnic identity formation (Erikson, 1968; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014), it is important to study how cultural orientations are formed during adolescence. Parents may play a significant role in developing adolescents’ cultural orientations. Previous studies have revealed that adolescents’ values and cultural orientations are similar to their parents’ (Barni, Knafo, Ben-Arieh, & Haj-Yahia, 2014; Costigan & Dokis, 2006; Roest, Dubas, & Gerris, 2010; W. A. Vollebergh, Iedema, & Raaijmakers, 2001). Parents’ cultural socialization may partly explain the link between parental and adolescent cultural orientations.

Previous studies have demonstrated the influence of parental ethnic socialization on the development of ethnic minority adolescents’ ethnic identity or orientation (Hernández, Conger, Robins, Bacher, & Widaman, 2014; Knight et al., 2011; Umaña-Taylor, Zeiders, & Updegraff, 2013; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009). For example, Knight et al. (2011) found that parents’, especially mothers’, Mexican American values related to their ethnic socialization, which in turn related to their adolescents’ ethnic identity and Mexican American values. To date, the role that parents may play in the development of cultural orientations other than ethnic orientation has been understudied. This is an important issue that requires more investigation, because a) ethnic minorities in the United States can develop multiple cultural orientations (Ferguson, Bornstein, & Pottinger, 2012; Kim, Gonzales, Stroh, & Wang, 2006) and b) in addition to ethnic socialization, parents may also adopt other cultural socialization beliefs, such as bicultural socialization beliefs (John & Montgomery, 2012; Lieber et al., 2004), which may relate not only to adolescents’ ethnic orientation but also to other cultural orientations. These two points are discussed in more detail below.

Tridimensional Model of Acculturation

Acculturation is generally defined as a process of change in cultural identity, values, and behaviors following intercultural contact (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). In the field of acculturation studies, the bidimensional model (Berry, 1980) is currently the dominant theoretical model of acculturation (Flannery et al., 2001; Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000). It proposes that acculturation involves two independent processes: maintaining the ethnic culture and adapting to the mainstream culture (Flannery et al., 2001; Ryder et al., 2000). Despite the plethora of acculturation studies using the bidimensional model (Chen et al., 2014; Kim, Chen, Li, Huang, & Moon, 2009; Lim et al., 2008; Ryder et al., 2000), researchers have recently begun to realize the limitations of this model. The bidimensional model regards the European American mainstream culture as the sole destination culture for immigrants, thus implying that the United States has a homogeneous culture (Ferguson et al., 2012). However, the United States is a multicultural society, in which the European American mainstream culture coexists with numerous ethnic minority cultures: for example, African American culture, Mexican American culture, and Chinese American culture. Besides European American culture, U.S. immigrants may also refer to these ethnic minority cultures, which also exist in the new host country (Ferguson et al., 2012).

Therefore, researchers are now proposing a tridimensional model, suggesting that immigrants can orient toward a subculture in the host country that may capture characteristics of both the ethnic culture and the mainstream culture and accommodate exposure and orientation to multiple ethnic, non-mainstream cultures (Ferguson et al., 2014; Flannery et al., 2001). A few empirical studies have uncovered initial evidence for the efficacy of adopting this tridimensional model. For example, Ferguson et al. (2012) found that Jamaican immigrants in the U.S. oriented toward Jamaican, African American, and European American cultures. Moreover, they found that Jamaican and other Black U.S. immigrants were more oriented toward African American culture than European American culture. Another study of Asian American families proposed that Asian, Anglo, and Asian American orientations have distinct meanings for Asian Americans (Kim et al., 2006); they also found that marginalization of Asian American orientation had a unique effect on individuals’ depressive symptoms even when controlling for marginalization of Anglo orientation and Asian orientation.

Similarly, Chinese Americans may orient to Chinese American culture, in addition to Chinese and American cultures. Chinese American culture, as a hybrid of Chinese and American cultures, integrates components of both cultures, but is more than the sum of those two cultures (Flannery et al., 2001). For example, “tiger parenting,” which was first brought to wide public attention as a “typical” Chinese American parenting style by a Chinese American mother (Chua, 2011), is neither a traditional Chinese parenting style nor a typical American parenting style. Characterized by high levels of both positive parenting (e.g., democratic parenting) and negative parenting (e.g., shaming), tiger parenting is related to the Chinese cultural emphasis on academic achievement and family obligation as well as to the American cultural emphasis on granting children autonomy (Kim, Wang, Orozco-Lapray, Shen, & Murtuza, 2013). Thus, “tiger parenting” exemplifies new cultural values and behaviors that originated in, but are distinct from, Chinese and American cultural values and behaviors.

According to tridimensional acculturation theory, Chinese American orientation may be correlated to Chinese and American orientations, but should nonetheless be considered distinct from them; this theory is also different from the traditional concept of biculturalism, which is characterized by high orientation to both ethnic and mainstream cultures (Flannery et al., 2001; Nguyen & Benet-Martínez, 2013). While Chinese American orientation may be a form of biculturalism, not all bicultural individuals necessarily endorse Chinese American orientation, because bicultural individuals may vary in their degree of bicultural identity integration (i.e., how much the dual cultural identities intersect or overlap), ranging from discrete and conflicting dual cultural identities to integrated and harmonious cultural identities (Benet-Martínez & Haritatos, 2005; Huynh, Nguyen, & Benet-Martínez, 2011). Benet-Martínez and her colleagues have revealed that individuals who score high on measures of bicultural identity integration also experience low conflict and high harmony between ethnic and American cultures, and tend to see themselves as part of a combined, third, emerging culture. These studies imply that an orientation toward an integrated culture (e.g., Chinese American culture) may represent a blended form of biculturalism, one that indicates a high degree of bicultural identity integration. However, by focusing on the relation between ethnic and American orientations, these bicultural identity integration studies are still adopting the bidimensional framework of acculturation, without explicitly measuring orientation toward a third culture (e.g., Chinese American). To test the theoretical assumptions of the tridimensional acculturation model, we directly assess Chinese American orientation and its relation with bicultural socialization beliefs.

Parental Cultural Orientations and Bicultural Socialization

A small yet growing body of research suggests that ethnic minority parents in the U.S. (e.g., Chinese immigrants and Indian immigrants) hold bicultural socialization beliefs (Cheah et al., 2013; John & Montgomery, 2012; Lieber et al., 2004; Uttal, 2011). These parents believe that it is important for their children to adopt both their ethnic culture and the U.S. culture. For example, some Chinese American parents reported that, even though they want their children to follow the Chinese way of doing things, they know that children should follow some American ways to ensure a good future in the United States (Lieber et al., 2004).

Parents’ cultural orientations may relate to their cultural socialization beliefs (Cheah et al., 2013; Roche et al., 2013). Because bicultural socialization beliefs emphasize the importance of both cultures, ethnic and mainstream, both Chinese and American orientations may be positively associated with parents’ bicultural socialization beliefs. The interaction effect of Chinese and American orientations on bicultural socialization beliefs may also be significant, as bicultural parents who are oriented toward both Chinese and American cultures may be more likely to hold bicultural socialization beliefs (Berry, 1980). Most importantly, parents’ Chinese American orientation should uniquely predict parents’ bicultural socialization beliefs, above and beyond Chinese orientation, American orientation, and the interaction of Chinese and American orientations, given that Chinese American orientation is theoretically distinct from the other two constructs. Furthermore, parents’ Chinese American orientation may be the most robust predictor of parents’ bicultural socialization beliefs if Chinese American orientation represents a blended form of biculturalism.

Parental Bicultural Socialization and Adolescent Cultural Orientations

Parental bicultural socialization beliefs may influence children’s cultural orientations through at least two pathways. First, parents with bicultural socialization beliefs may be more likely to expose their children to bicultural environments, and promote chances for their children to learn both cultures (Uttal, 2011). Second, parents’ bicultural socialization beliefs may be internalized by their children (Bisin & Verdier, 2001; W. A. Vollebergh et al., 2001). In other words, children whose parents believe in the importance of bicultural socialization are more likely to believe they should learn from both the ethnic and the U.S. cultures (e.g., “I want to be American but still retain parts of Chinese culture”). And children’s own bicultural socialization beliefs may in turn influence their cultural orientations, as their beliefs guide their choice of activities (Fazio, 1990).

Although parents can influence the environments of both children and adolescents, the pathway through parental socialization practices (e.g., exposing children to bicultural environments) may be more relevant to young children, as parents often have greater control over their young children’s environments; for example, parents could decide to put their child in a childcare center with diverse cultures (Uttal, 2011). The other pathway, through children’s internalization of parental bicultural socialization beliefs, may be especially important for adolescents, given that adolescents have more autonomy in selecting their own activities and are exposed to wider social contexts in which parents have less control (Barber, Olsen, & Shagle, 1994; Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Daddis, 2004). Thus, because the current study examines adolescents in high school, we focused on the second pathway: intergenerational transmission of cultural orientations through adolescents’ internalization of parental bicultural socialization beliefs.

Parent and Adolescent Gender

Prior studies on cultural socialization have tended to focus more on the role of mothers, suggesting that mothers may play a more significant role in transmitting cultural values to their children (Knight et al., 2011; Schönpflug, 2001; Su & Costigan, 2009). For example, Su and Costigan (2009) found that in immigrant Chinese families in Canada, mothers’ (but not fathers’) expectations of family obligation related to children’s feelings of ethnic identity. However, fathers may play an important role in cultural socialization as well (Kim et al., 2006; Paquette, 2004; Zeiders, Updegraff, Umaña-Taylor, McHale, & Padilla, 2015). Prior studies have demonstrated that fathers tend to be more involved in American culture than mothers (Kim et al., 2006) and are generally more responsible for socializing children into the outside world (Paquette, 2004). Thus, it is important to include both fathers and mothers and examine their potentially different roles in the cultural socialization of their children.

Including both fathers and mothers also allows researchers to take into account the interdependence between mothers and fathers (Cox & Paley, 2003). Mothers and fathers can mutually influence each other (Cox & Paley, 2003), which means that parents’ cultural orientations may relate not only to their own bicultural socialization beliefs (i.e., actor effects), but also to their spouse’s bicultural socialization beliefs (i.e., partner effects). It is important to consider such mutual influence to provide a more nuanced and accurate picture regarding the roles of both parents in cultural socialization. Therefore, the current study included both parents and simultaneously examined both actor and partner effects (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006).

Besides potential parent gender differences, there may also be adolescent gender differences in intergenerational cultural transmission. According to the sex role model of socialization, fathers transmit their values mostly to their sons and mothers mostly to their daughters (Roest et al., 2010; W. Vollebergh, Iedema, & Meuss, 1999). Hence, there may be more similarities in cultural orientations and bicultural socialization beliefs for same-sex (vs. opposite-sex) parent-child dyads.

The Current Study

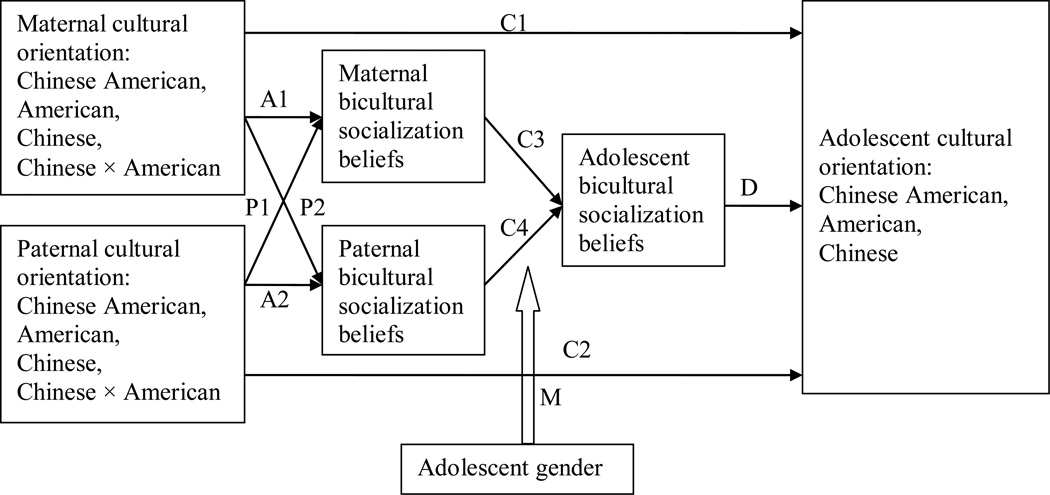

The present study has three goals. The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1. The first aim is to test the tridimensional model by assessing three cultural orientations in Chinese American families: Chinese American orientation, Chinese orientation, and American orientation. We propose that Chinese American orientation is correlated to, yet distinct from, Chinese orientation, American orientation, and the traditional conception of biculturalism. Specifically, we propose that Chinese American orientation will have a unique effect on bicultural socialization beliefs, above and beyond Chinese and American orientations, including the interaction between them. The second and primary aim is to examine a potential mechanism through which parental cultural orientations may relate to adolescents’ cultural orientations. We propose that parents’ cultural orientations will significantly relate to parents’ own (A paths) and their partners’ (P paths) bicultural socialization beliefs. Further, parents’ bicultural socialization beliefs will be internalized by adolescents as their own bicultural socialization beliefs (C3 & C4 paths), which in turn will relate to adolescents’ cultural orientations (D path). In addition, we aim to examine whether the intergenerational links for bicultural socialization beliefs and cultural orientations differ across parent and adolescent gender (M path). We expect that the intergenerational association will be stronger in same-sex (vs. opposite-sex) parent-child dyads.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of cultural transmission from parents to adolescents. A paths are actor effects, P paths are partner effects, C paths are effects from parents to their children, and the D path is the association between adolescents’ own bicultural socialization beliefs and cultural orientations.

Method

Participants

Participants of the current study included 350 adolescents and their fathers and mothers in Chinese American families. Adolescents were in eleventh or twelfth grade, with ages ranging from 16 to 19 years old (M = 17.04, SD = 0.73). Females comprise 58% of the adolescent sample. The majority of fathers (87%) and mothers (90%) were born outside the U.S., whereas most of the adolescents (75%) were born in the United States. Specifically, among adolescents, 25% are first-generation immigrants, 67% are second-generation, and 8% are third-generation. The majority of foreign-born parents migrated from southern provinces of China or Hong Kong, with fewer than 10 families hailing from Taiwan. Parents’ occupations ranged from low-skill (e.g., construction work) to professional work (e.g., banking or computer programming). The median (and average) family income was in the range of $45,001 to $60,000. The median (and average) parental education level was finished high school, for both fathers and mothers. Most of these families speak Cantonese, with less than 10% speaking Mandarin as their home language. The majority of adolescents (89%) were living with their biological mothers and fathers; 8% of adolescents were living with a single parent; others were living with a biological parent and a step parent or did not report their living situation.

Procedure

The data for the current study are from a three-wave longitudinal study, with the first wave of data collected when the target adolescents were in 7th or 8th grade, and later waves of data being collected every four years. The current study uses data from the second wave, because we focus on adolescence and also because key concepts such as Chinese American orientation and bicultural socialization beliefs were not measured at Wave 1. Participants in the longitudinal study (n=444) were initially recruited from seven middle schools in two school districts in major metropolitan areas of Northern California. At these schools, Asian Americans comprised at least 20% of the student body. With the aid of school administrators, students who self-identified as being of Chinese origin were targeted. All of these families were eligible to participate and were sent a letter describing the research project in both English and Chinese (traditional and simplified). The forty-seven percent of these families that returned parent consent(s) and adolescent assent received a packet of questionnaires for the mother, father, and target adolescent in the household. Participants were instructed to complete the questionnaires alone and not to discuss their answers with others. They were also instructed to seal their questionnaires in the provided envelopes immediately after completion. Within approximately 2–3 weeks after sending the questionnaire packet, research assistants visited each school to collect the completed questionnaires during the students’ lunch periods. Among the families who agreed to participate, 76% returned surveys. Four years after the initial wave, families were asked to participate in the second wave. Families who returned questionnaires were compensated a nominal amount of money ($30 at Wave 1 and $50 at Wave 2) for their participation. Questionnaires were prepared in English and Chinese (traditional and simplified). The questionnaires were first translated to Chinese and then back-translated to English. The majority of parents (over 70 percent) used the Chinese language version of the questionnaire and the majority (over 80 percent) of adolescents used the English version.

The attrition rate from Wave 1 to Wave 2 was 21%. Attrition analyses were conducted at Wave 2 to compare families who participated with those who had dropped out on demographic characteristics (i.e., adolescent age, gender, nativity, and parent age, nativity, education level, and family income). Only two significant differences emerged: boys were less likely than girls to have continued participating (χ2 (1) = 12.66, p< .001), and foreign-born fathers were less likely than U.S.-born fathers to have continued participating (χ2 (1) = 4.16, p< .05).

Measures

Cultural orientations

Chinese and American orientations were measured by the Vancouver Index of Acculturation (Ryder et al., 2000), which consists of 10 items on Chinese orientation and 10 corresponding items on American orientation regarding values, behaviors, traditions, and social interactions. Chinese American orientation was also assessed using the same 10 items, except that the word “Chinese” or “American” was changed to “Chinese American.” A sample item is, “I often follow Chinese/American/Chinese American cultural traditions.” Using a scale of 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neutral/depends), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree), mothers, fathers, and adolescents separately responded to each of the items with regard to each of the three cultural orientations. An average score of the 10 items was computed for each cultural orientation and each informant, with a higher score representing a stronger orientation (Chinese orientation, α = .86 to .89 across informants; American orientation, α = .79 to .88 across informants; Chinese American orientation, α = .89 to .91 across informants). As the Chinese American orientation scale was used for the first time in the current study, we also applied one-factor confirmatory factor analysis to assess its psychometric properties simultaneously for mothers, fathers, and adolescents. Model fit was good, χ2(365) =640.07, p < .001, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05[.04, .05], SRMR =.06. All of the items loaded significantly on the latent factor across informants, λs = .38 to .79, p < .001.

Bicultural socialization beliefs

Parental bicultural socialization beliefs were measured by three items created based on qualitative research by Lieber, Nihira, and Mink (2004): “To be successful in America, my child needs to pick up some American values and behaviors”; “I want my child to be American but still retain parts of his or her Chinese culture”; and, “Even though I would like my child to follow the Chinese way of doing things, I know she or he should follow some American ways to ensure a good future in America.” Adolescents’ own beliefs about bicultural socialization were assessed by three corresponding items (i.e., “To be successful in America, I need to pick up some American values and behaviors”; “I want to be American but still retain parts of my Chinese culture”; and “Even though I would like to follow the Chinese way of doing things, I know I should follow some American ways to ensure a good future in America”). Fathers, mothers, and adolescents self-reported on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher mean scores reflecting a higher degree of belief in the importance of bicultural socialization (α = .77 to .88 across informants). We applied one-factor confirmatory factor analysis to assess the psychometric properties of this measure simultaneously for mothers, fathers, and adolescents. Model fit was good, χ2(23) =32.42, p = .09, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03[.00, .06], SRMR =.03. All of the items loaded significantly on the latent factor across informants, λs = .62 to .90, p < .001.

Covariates

The present study controlled for several covariates. As previous studies have indicated that intergenerational similarities in cultural orientation may be partly explained by family members’ shared social status (Barni et al., 2014; W. A. Vollebergh et al., 2001), the current study includes family income and parental educational level as covariates to address this possibility. In addition, we also controlled for adolescents’ age and generational status, given that these may relate to adolescents’ cultural orientations (Flannery et al., 2001; W. A. Vollebergh et al., 2001). Using a scale of 1 (no formal schooling) to 9 (finished graduate degree), parents reported on their highest education level. Parents reported on their family income before taxes during the past year, using a scale divided into $15,000 increments, ranging from 1 ($15,000 or under) to 12 ($165,001 or more). In this study, family income was indexed by the average of the father’s and mother’s reports in each household. Adolescents’ generational status was identified from their own and their parents’ nativity (0 = U.S. born, 1= foreign born). First-generation immigrants are those born outside of the U.S., second-generation are those born in the U.S. with at least one foreign-born parent, and third-generation are those born in the U.S. with U.S.-born parents.

Results

Plan of Analyses

Data analyses proceeded in three steps. First, we conducted descriptive and correlational analyses for key study variables. Second, to test our conceptual model (see Figure 1), we conducted path analysis using Mplus 7.31(Muthén & Muthén, 1998 – 2015). Mplus uses the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation method to handle missing data.

The path model tested the direct and indirect pathways linking parental and adolescent cultural orientations and bicultural socialization beliefs. Inferences for the indirect effects were estimated using the delta method (Muthén & Muthén, 1998 – 2015). Interaction products for continuous variables were included in the path model to test interaction effects. Before creating interaction terms by multiplying the predictor and the moderator, we first centered predictors and moderators (i.e., parental cultural orientations and bicultural socialization beliefs). Third, to test whether the links between parents’ and adolescents’ variables varied across parent and adolescent gender, we used Wald tests of parameter constraints and multi-group comparison. Parental educational level, family income, and adolescent generational status, age, and gender (except when it was tested as a moderator) were included in all models as covariates.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations of the key study variables. First, we found that, on average, participants, including fathers (M = 3.54, SD = .53), mothers (M = 3.58, SD = .57), and adolescents (M = 3.73, SD = .60), reported a mean score between “neutral/depends” to “agree” on Chinese American orientation, suggesting that they agreed to a certain extent that they endorsed Chinese American values, behaviors, traditions, and social interactions. One-way ANOVA demonstrated that adolescents’ Chinese American orientation varied across generational status, F(2,339) = 6.22, p <.01, with the second generation (M = 3.80, SD = .60) being higher than the first (M = 3.61, SD = .53) and third (M = 3.44, SD = .69). Thus, two dummy variables (labeled “first generation” and “third generation”) were created to represent adolescent generational status, with the second generation being the reference group. These two dummy variables were included as covariates in the analyses of path models.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Zero-Order Correlations among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.A Chinese American orientation | — | 3.73 | 0.60 | |||||||||||

| 2.A Chinese orientation | .63*** | — | 3.79 | 0.56 | ||||||||||

| 3.A American orientation | .42*** | .45*** | — | 3.80 | 0.44 | |||||||||

| 4.A Bicultural socialization beliefs | .24*** | .18*** | .17*** | — | 3.31 | 0.73 | ||||||||

| 5.M Chinese American orientation | .25*** | .17** | .17** | .14* | — | 3.58 | 0.57 | |||||||

| 6.M Chinese orientation | .26*** | .32*** | .11* | .16** | .40*** | — | 3.86 | 0.50 | ||||||

| 7.M American orientation | .03 | −.05 | .21*** | .06 | .40*** | .18*** | — | 3.37 | 0.49 | |||||

| 8.M Bicultural socialization beliefs | .19*** | .19*** | .16** | .23*** | .35*** | .33*** | .13* | — | 3.78 | 0.69 | ||||

| 9.F Chinese American orientation | .18** | .21*** | .27*** | .15* | .44*** | .30*** | .31*** | .26*** | — | 3.54 | 0.53 | |||

| 10.F Chinese orientation | .27*** | .35*** | .20*** | .18** | .27*** | .54*** | .04 | .30*** | .45*** | — | 3.84 | 0.51 | ||

| 11.F American orientation | .02 | −.09 | .17** | −.01 | .20*** | −.03 | .40*** | .02 | .33*** | .05 | — | 3.39 | 0.50 | |

| 12.F Bicultural socialization beliefs | .20*** | .20*** | .08 | .12* | .16* | .15* | −.03 | .38*** | .27*** | .28*** | .13* | — | 3.85 | 0.70 |

Note: A=Adolescent, M=Mother, F=Father. (N=350).

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Second, correlation analyses demonstrated that Chinese American orientation was moderately associated with Chinese orientation (rs range from .40 to .63 across informants) and American orientation (rs range from .33 to .42 across informants). These moderate correlations suggest that Chinese American orientation is correlated to, yet probably distinct from, Chinese orientation and American orientation.

Moreover, as shown in Table 1, there were positive associations between parental and adolescent cultural orientations (rs range from .12 to .35). We also found positive associations between parental and adolescent bicultural socialization beliefs (r=.23 for mother-adolescent dyads, r=.12 for father-adolescent dyads). Finally, there were positive associations between cultural orientations and bicultural socialization beliefs for both parents (rs range from .13 to .35) and adolescents (rs range from .17 to .24).

Analysis of Path Model

We first tested the conceptual model with all path parameters freely estimated. Model fit for this basic model was good, χ2(38) = 53.75, p = .05; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03 [.00, .05]; SRMR = .03. Then, we tested whether the links between parental orientations and parental bicultural socialization beliefs differed across parental gender. Wald tests of parameter constraints demonstrated that the associations between parental cultural orientations and parental bicultural socialization beliefs were similar for mothers and for fathers, W(8) = 8.72, p =.37. As there is little, if any, theoretical basis for believing that these associations should be different between mothers and fathers, and because we did not find any empirical evidence for gender difference, these associations were constrained to be equal across parental gender (i.e., A1 paths=A2 paths, P1 paths = P2 paths) to obtain a more parsimonious model. Model fit for the final model was good, χ2(46) = 62.36, p = .05; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03 [.00, .05]; SRMR = .03. Standardized parameter estimates for all paths are presented in Table 2, and significant paths are highlighted in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Cultural Transmission Pathways from Parents to Their Children

| Pathway/variable | β | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR Chinese American orie. → PR socialization beliefs (actor effect) | .21 | .05 | .00 |

| PR Chinese orie. → PR socialization beliefs (actor effect) | .12 | .05 | .01 |

| PR American orie. → PR socialization beliefs (actor effect) | .12 | .05 | .01 |

| PR Chinese×PR American orie.→ PR socialization beliefs (actor effect) | −.08 | .04 | .04 |

| PR Chinese American orie. → PR socialization beliefs (partner effect) | .10 | .05 | .04 |

| PR Chinese orie. → PR socialization beliefs (partner effect) | .07 | .06 | .24 |

| PR American orie. → PR socialization beliefs (partner effect) | −.11 | .05 | .04 |

| PR Chinese×PR American orie.→ PR socialization beliefs (partner effect) | .07 | .05 | .16 |

| MR socialization beliefs → AR socialization beliefs | .21 | .06 | .00 |

| FR socialization beliefs → AR socialization beliefs | .04 | .07 | .61 |

| AR socialization beliefs → AR Chinese American orie. | .19 | .05 | .00 |

| AR socialization beliefs → AR Chinese orie. | .11 | .05 | .04 |

| AR socialization beliefs → AR American orie. | .15 | .05 | .01 |

| MR Chinese American orie. → AR Chinese American orie. | .17 | .06 | .01 |

| MR Chinese American orie. → AR Chinese orie. | .06 | .07 | .37 |

| MR Chinese American orie. → AR American orie. | .02 | .07 | .83 |

| MR Chinese orie. → AR Chinese American orie. | .14 | .07 | .05 |

| MR Chinese orie. → AR Chinese orie. | .12 | .07 | .09 |

| MR Chinese orie. → AR American orie. | .00 | .07 | 1.00 |

| MR American orie. → AR Chinese American orie. | −.09 | .06 | .17 |

| MR American orie. → AR Chinese orie. | −.06 | .06 | .39 |

| MR American orie. → AR American orie. | .06 | .07 | .38 |

| FR Chinese American orie. → AR Chinese American orie. | .02 | .07 | .80 |

| FR Chinese American orie. → AR Chinese orie. | .10 | .07 | .16 |

| FR Chinese American orie. → AR American orie. | .16 | .07 | .03 |

| FR Chinese orie. → AR Chinese American orie. | .10 | .08 | .18 |

| FR Chinese orie. → AR Chinese orie. | .15 | .07 | .04 |

| FR Chinese orie. → AR American orie. | .09 | .08 | .24 |

| FR American orie. → AR Chinese American orie. | .03 | .07 | .66 |

| FR American orie. → AR Chinese orie. | −.07 | .06 | .27 |

| FR American orie. → AR American orie. | .05 | .06 | .42 |

Note: PR=Parental report, MR=Mother report, FR=Father report, AR=Adolescent report, and orie. = orientation.

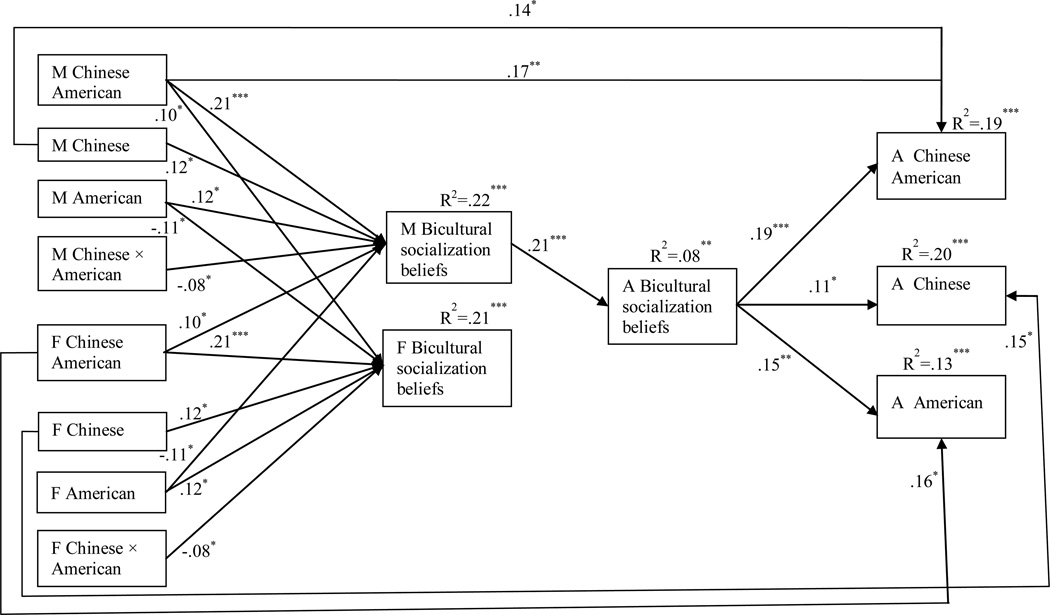

Figure 2.

Path model testing associations among parental and adolescent cultural orientations and bicultural socialization beliefs.

Note: Model fit statistics: χ2(46) = 62.36, p = .05; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03 [.00, .05]; SRMR = .03. Standardized coefficients are reported. Only significant paths are presented for simplicity. The model controlled for family income, parental education, and adolescent gender, age, and generational status. M=Mother; F=Father; A=Adolescent. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

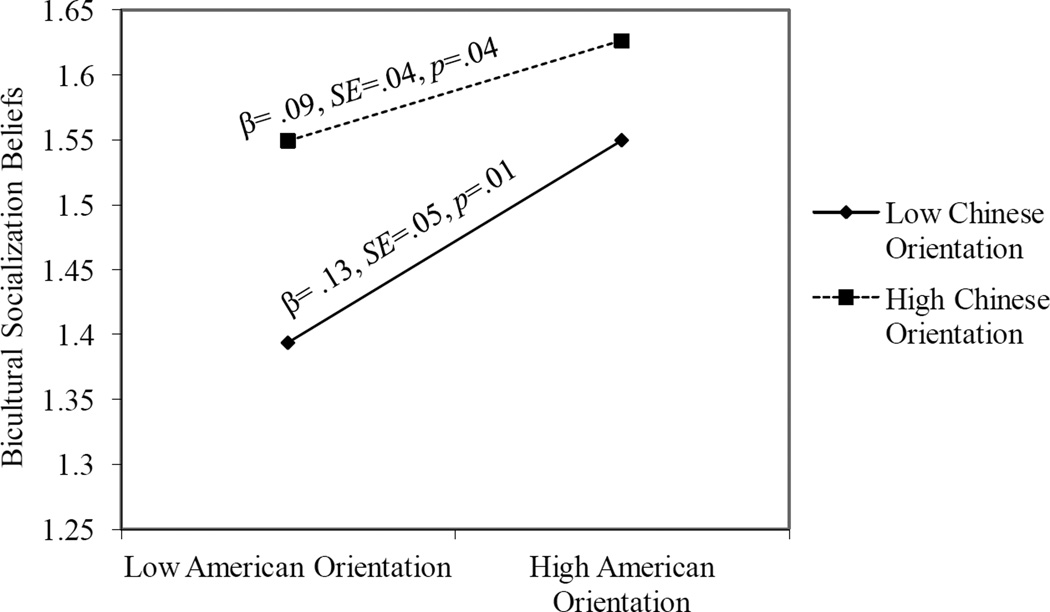

The results were generally consistent with our hypotheses. First, for the relationship between parental cultural orientations and parental bicultural socialization beliefs, parents’ Chinese, American, and Chinese American orientations were all positively associated with their own bicultural socialization beliefs. The interaction between Chinese orientation and American orientation was also significant. As shown in Figure 3, when parental Chinese orientation was lower, parental American orientation was more strongly associated with parental bicultural socialization beliefs. It is worth pointing out that Chinese American orientation uniquely predicted bicultural socialization beliefs, above and beyond Chinese and American orientations, as well as the interaction between the two. This suggests that Chinese American orientation is distinct from Chinese and American orientations, and may not be fully captured by the traditional conceptualization of biculturalism. Moreover, we found some evidence for partner effects: a) parents’ Chinese American orientation was positively associated with their spouses’ bicultural socialization beliefs, and b) parents’ American orientation was negatively associated with their spouses’ bicultural socialization beliefs.

Figure 3.

Interaction effect of Chinese orientation and American orientation on maternal bicultural socialization beliefs. The positive association between American orientation and bicultural socialization beliefs is stronger when Chinese orientation is lower (vs. higher).

Second, maternal (but not paternal) bicultural socialization beliefs were positively associated with adolescent bicultural socialization beliefs. Third, adolescents’ bicultural socialization beliefs positively related to adolescent Chinese American orientation, Chinese orientation, and American orientation. There were also some significant direct links between parental and adolescent cultural orientations. Testing of indirect effects from parental to adolescent cultural orientation demonstrated one significant indirect effect, which was from maternal Chinese American orientation to maternal bicultural socialization beliefs to adolescent bicultural socialization beliefs to adolescent Chinese American orientation (b = .01, SE =.004, p = .03).

Gender differences

The associations between parental and adolescent variables (bicultural socialization beliefs and cultural orientations) were not significantly different for mother-adolescent and father-adolescent dyads, W(10) = 13.12, p = .22, nor did they differ significantly across adolescent gender, W(20) = 13.76, p = .84.

Discussion

Is there an intergenerational transmission of cultural orientation from parents to adolescents in Chinese American families? If so, what are the mechanisms through which these cultural orientations are transmitted? While previous studies have documented intergenerational transmission of ethnic cultural orientation from parents to adolescents through parental ethnic socialization, few studies have explored potential mechanisms that may link parents’ and adolescents’ other cultural orientations. Adopting a tridimensional model of acculturation (Ferguson et al., 2014; Flannery et al., 2001), the present study examined Chinese American parents’ and adolescents’ cultural orientations toward Chinese, American, and Chinese American cultures. We provided empirical evidence for the tridimensional acculturation model and identified an indirect pathway from maternal to adolescent Chinese American orientation through adolescents’ internalization of mothers’ bicultural socialization beliefs.

Evidence for Tridimensional Acculturation Model

The present study has provided some evidence for the tridimensional acculturation model. First, we found that the average scores for mothers’, fathers, and adolescents’ Chinese American orientation were above three (neutral/depends) on a five-point scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree), indicating that they endorsed Chinese American values, behaviors, traditions, and social interactions to a degree higher than “neutral/depends.” Second, we found that Chinese American orientation was moderately associated with Chinese and American orientations, suggesting that Chinese American orientation was related to, yet likely distinct from, Chinese and American orientations. Third, we demonstrated the predictive validity of Chinese American orientation by showing its association with parental bicultural socialization beliefs. Moreover, our finding of a unique effect of Chinese American orientation on parental bicultural socialization beliefs – controlling for Chinese orientation, American orientation, and the interaction between the two – further indicates that this third orientation is distinct from Chinese and American orientations, in a way that goes beyond the traditional conceptualization of biculturalism. Our results are consistent with Ferguson and her colleagues’ work on Black immigrants, which has demonstrated that Black immigrants orient to their ethnic culture, the mainstream U.S. culture, and also the African American culture (Ferguson, 2013; Ferguson et al., 2012; Ferguson et al., 2014). These prior studies and our findings indicate that a tridimensional or multidimensional model may be more appropriate for use in multicultural contexts.

When new Chinese immigrants arrive in the United States, they often join existing Chinese American communities (e.g., Chinatown or Chinese American churches) and are eager to know the stories of Chinese Americans who came to the U.S. earlier (Cao, 2005). This is particularly true in places with a long history of Chinese immigration and a dense population of Chinese Americans, such as in New York and California (where our research took place) (Zhou, 2010). It may be more important for Chinese immigrants residing in such places to adapt to the Chinese American culture, rather than to the mainstream American culture, because Chinese Americans are the people with whom they are most likely to interact on a daily basis. Fuligni et al.(2008) found that a substantial proportion of adolescents from Chinese immigrant families in California labeled themselves as Chinese American, rather than as Chinese or American. Therefore, the extent to which Chinese immigrants endorse Chinese American orientation, compared to other orientations, may be more strongly linked to their adjustment (Kim et al., 2006). For this reason, assessing Chinese American orientation is important for acculturation studies focusing on Chinese Americans.

Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Orientations

In the present study, we found that there were significant correlations between parents’ and adolescents’ cultural orientations; parents’ and adolescents’ bicultural socialization beliefs partly explained these intergenerational associations. Specifically, there is intergenerational transmission of Chinese American orientation from mothers to adolescents through maternal and adolescent bicultural socialization beliefs. This finding is consistent with prior studies demonstrating the role of ethnic socialization in developing ethnic cultural orientation (Hernández et al., 2014; Knight et al., 2011; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2013; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009); all emphasize the role of parental cultural socialization in shaping children’s cultural orientations. The intergenerational transmission of cultural orientations through bicultural socialization beliefs was found only for Chinese American orientation, and not for other cultural orientations, despite the fact that bicultural socialization beliefs were associated with all three cultural orientations. This is probably because, among the three cultural orientations assessed, Chinese American orientation had the most robust relation with bicultural socialization beliefs. Because an orientation toward Chinese American culture may represent a more integrated form of biculturalism (Benet-Martínez & Haritatos, 2005; Huynh et al., 2011), parents who demonstrate a stronger Chinese American orientation may have more positive bicultural experiences (e.g., less culture conflict). Therefore, they may be most likely to socialize their children toward both Chinese and American cultures. When adolescents internalize their parents’ bicultural socialization beliefs, they want to endorse both Chinese and American cultures. Given their beliefs, they may be more likely to participate in activities held in Chinese American communities and orient to Chinese American culture, which integrates Chinese and American cultures.

While bicultural socialization has been demonstrated in prior qualitative studies on ethnic minority parents (Cheah et al., 2013; John & Montgomery, 2012; Lieber et al., 2004; Uttal, 2011), this study is among the first to assess this approach to cultural socialization and to identify its role in developing adolescent cultural orientations. Compared to ethnic socialization, bicultural socialization may better capture ethnic minority parents’ approach to cultural socialization, as it recognizes parents’ role in shaping children’s cultural orientations more generally, rather than implying that their influence is limited to passing on their heritage culture. However, the present study examined only beliefs about the importance of adopting both the Chinese and American cultures. Future studies should also investigate parents’ actual socialization practices, and how these correspond to their bicultural socialization beliefs. For example, do they require their children to speak both Chinese and English, encourage their children to have both Chinese and American friends, and create opportunities for their children to develop bicultural skills? Examination of parental bicultural socialization practices, along with beliefs, may provide us with further insights regarding the development of children’s cultural orientations.

The current study has moved beyond prior cultural socialization studies by demonstrating initial evidence for the role of bicultural socialization in developing multiple cultural orientations. However, more sophisticated cultural socialization theories should be developed to reflect better the advances of the tridimensional acculturation model. Since ethnic minorities in the United States may orient to multiple cultures – including their ethnic culture, the mainstream American culture, and a third culture (e.g., Chinese American culture, African American culture) – it is likely that ethnic minority parents socialize their children toward each of these cultures. Scholars need to develop a cultural socialization theory that captures the complexity of cultural socialization in the context of multiple cultural orientations.

Parent and Adolescent Gender

Overall, we found no significant gender difference, suggesting that the intergenerational associations of cultural orientations and socialization beliefs are generally similar across parent and adolescent gender. However, we did find that adolescents’ bicultural socialization beliefs were associated with their mothers’, but not fathers’, bicultural socialization beliefs. Even though this particular finding did not reach the level of statistical significance, it seems to provide some support for prior studies suggesting that in the realm of cultural socialization, it is mothers who play the more significant role (Knight et al., 2011; Schönpflug, 2001; Su & Costigan, 2009). Taking a holistic view, our study indicates that mothers and fathers both play important roles in forming adolescents’ cultural orientations. Although there was no significant indirect effect of paternal cultural orientations on adolescent cultural orientations through paternal and adolescent bicultural socialization beliefs, paternal cultural orientations had some unique direct effects on adolescent cultural orientations (i.e., paternal Chinese American orientation → adolescent American orientation; paternal Chinese orientation → adolescent Chinese orientation). This suggests that fathers may affect adolescents’ cultural orientations in direct ways, or through other mechanisms (e.g., actual socialization practices), rather than through transmission of bicultural socialization beliefs; this is a topic worthy of future investigation. It is also important to note that parents’ cultural orientations (in the case of Chinese American orientation and American orientation) related to not only their own but also their spouses’ bicultural socialization beliefs. Therefore, even if paternal cultural socialization did not have a unique effect on adolescent cultural orientations, paternal cultural orientations may relate to maternal cultural socialization, which may in turn relate to adolescent cultural orientations. Nevertheless, in the current study, the indirect pathways through spouses’ bicultural socialization beliefs did not reach statistical significance. Future studies should investigate the possibility of partner effects by examining the potential indirect pathway through spouses’ cultural socialization. The significant actor and partner effects identified in the current study are in line with family systems theory, which emphasizes that a family is an interdependent, dynamic system in which family members’ experiences are interrelated and can mutually influence each other (Cox & Paley, 2003). Therefore, it is important to involve both mothers and fathers in studies on family acculturation, to take into account their mutual influence on each other.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations and caveats should be kept in mind. First, this is a cross-sectional correlational study, which means that it cannot indicate causal relationships. Our inferences regarding the direction of the relations among study variables are based on the existing literature. Including multiple informants in the current study reduced the problem of common-method variance to some degree, thus possibly strengthening our conclusions. However, any causal implications taken from our results should be applied with caution. Although experimental studies are required to determine the direction of causal relationships, future studies using a longitudinal, rather than cross-sectional design, may provide better information about the direction of the observed relationships. Second, intergenerational transmission of cultural orientations may be moderated by parents’ and adolescents’ immigration status. However, the present study was not able to test this possibility, because the samples for U.S.-born parents and foreign-born adolescents were too small to conduct multi-group comparisons.

A third limitation relates to the measure of bicultural socialization. We assessed a relatively narrow set of indicators of bicultural socialization by asking parents their beliefs regarding what cultures their children should adopt. Future studies should include other bicultural socialization indicators, such as actual socialization practices, to provide additional insights on the development of adolescent cultural orientations. Moreover, one item (“To be successful in America, I need to pick up some American values and behaviors”) assumes that Chinese Americans have been socialized toward some Chinese values and behaviors by default. It may be better to adjust this item to capture bicultural beliefs more explicitly, by changing it as follows: “To be successful in America, I need to pick up both Chinese and American values and behaviors”.

Fourth, besides the three cultural orientations measured in the present study, Chinese Americans may also orient to a more pan-ethnic, broader hybrid culture, such as Asian American culture (Kim et al., 2006). Future studies are necessary to compare Chinese American orientation and Asian American orientation, so as to determine whether they are distinct from each other, and if so, which one better predicts individual outcomes. Given the heterogeneity of Asian American culture (Xia, Do, & Xie, 2013), however, we believe that Chinese American culture is more relevant to the study of Chinese immigrants in the United States. Scholars on Asian Americans argue that the pan-ethnic label (“Asian American”) is a more political identity, which individuals and groups can choose to join or ignore (Espiritu, 1993). At least one study has demonstrated that Chinese Americans, particularly those in the second and third generation, tend to choose a hyphenated label (“Chinese-American”) to describe themselves, rather than a national label (“Chinese”), a pan-ethnic label (“Asian American”), or an American label (“American”) (Fuligni et al., 2008).

Fifth, the similarities between the cultural orientations of parents and their children may be due, at least in part, to their shared environment and social status. Although our study has adjusted for socioeconomic variables and generational status, there may be other potentially confounding factors, such as the overlapping social networks of parents and children and the social dynamics of the communities in which they live, which should be taken into account in future studies. Finally, our participants were from an area with a high percentage of Chinese Americans and a long history of Chinese immigration. As community characteristics – such as migration history, ethnic concentration, and neighborhood disadvantages – may influence the acculturation process (Kiang, Perreira, & Fuligni, 2011; Liu, Lau, Chen, Dinh, & Kim, 2009; White, Zeiders, Knight, Roosa, & Tein, 2014), future studies should test whether our results can be replicated in other Chinese American samples.

Conclusion

The present study is among the first to apply the tridimensional acculturation model to study Chinese Americans’ cultural orientations. Our results provided empirical evidence for the tridimensional model, suggesting that a tridimensional model may better capture Chinese Americans’ (and maybe other ethnic minority groups’) acculturation experiences in the United States. Most importantly, by revealing an indirect pathway of intergenerational transmission of Chinese American orientation through adolescents’ internalization of parental bicultural socialization beliefs, we highlight the role bicultural socialization may play in intergenerational transmission of cultural orientations. Investigating these issues of tridimensional acculturation and the intergenerational transmission of cultural orientation via parental bicultural socialization is critical, given the large immigrant population in the United States, a country that is becoming increasingly multicultural.

Acknowledgments

Funding. Support for this research was provided through awards to Su Yeong Kim from (1) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development 5R03HD051629-02 (2) Office of the Vice President for Research Grant/Special Research Grant from the University of Texas at Austin (3) Jacobs Foundation Young Investigator Grant (4) American Psychological Association Office of Ethnic Minority Affairs, Promoting Psychological Research and Training on Health Disparities Issues at Ethnic Minority Serving Institutions Grant (5) American Psychological Foundation/Council of Graduate Departments of Psychology, Ruth G. and Joseph D. Matarazzo Grant (6) California Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Extended Education Fund (7) American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Massachusetts Avenue Building Assets Fund, and (8) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development 5R24HD042849-14 grant awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin.

Biographies

Su Yeong Kim

Department of Human Development and Family Sciences

University of Texas at Austin

Su Yeong Kim is an Associate Professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. She received her Ph.D. in Human Development from the University of California, Davis. Her research interests include the role of cultural and family contexts that shape the development of adolescents in immigrant and minority families in the U.S.

Yang Hou

Department of Human Development and Family Sciences

University of Texas at Austin

Yang Hou is a doctoral student in the Department of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research interests focus on how factors in family, school, and socio-cultural contexts relate to adolescents’ socio-emotional, behavioral, and academic development.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

SYK created the design of the study, conceived of the study and drafted portions of the manuscript; YH performed the statistical analysis and drafted portions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Su Yeong Kim, University of Texas at Austin, Department of Human Development and Family Sciences, 108 East Dean Keeton Street, Stop A2702, Austin, TX 78712, sykim@prc.utexas.edu, (512) 471-5524.

Yang Hou, University of Texas at Austin, Department of Human Development and Family Sciences, 108 East Dean Keeton Street, Stop A2702, Austin, TX 78712, houyang223@gmail.com, (512) 660-2236.

References

- Barber BK, Olsen JE, Shagle SC. Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development. 1994;65:1120–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barni D, Knafo A, Ben-Arieh A, Haj-Yahia MM. Parent-child value similarity across and within cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2014;45:853–867. [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martínez V, Haritatos J. Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1015–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In: Padilla AM, editor. Acculturation: Theory, models and some new findings. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1980. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bisin A, Verdier T. The economics of cultural transmission and the dynamics of preferences. Journal of Economic Theory. 2001;97:298–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cao N. The church as a surrogate family for working class immigrant Chinese youth: An ethnography of segmented assimilation. Sociology of Religion. 2005;66:183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CS, Leung CY, Zhou N. Understanding “tiger parenting” through the perceptions of Chinese immigrant mothers: Can Chinese and US parenting coexist? Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2013;4:30–40. doi: 10.1037/a0031217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SH, Hua M, Zhou Q, Tao A, Lee EH, Ly J, Main A. Parent-child cultural orientations and child adjustment in Chinese American immigrant families. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:189–201. doi: 10.1037/a0032473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua A. Battle hymn of the tiger mother. New York: Bloomsbury; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Dokis DP. Relations between parent-child acculturation differences and adjustment within immigrant Chinese families. Child Development. 2006;77:1252–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: W.W. Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Espiritu Y. Asian American panethnicity: Bridging institutions and identities. Philadephia, PA: Temple University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH. Multiple processes by which attitudes guide behavior: The mode model as an integrative framework. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 23. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 75–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson GM. The big difference a small island can make: How Jamaican adolescents are advancing acculturation science. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson GM, Bornstein MH, Pottinger AM. Tridimensional acculturation and adaptation among Jamaican adolescent-mother dyads in the United States. Child Development. 2012;83:1486–1493. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson GM, Iturbide MI, Gordon BP. Tridimensional (3D) acculturation: Ethnic identity and psychological functioning of tricultural Jamaican immigrants. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation. 2014;3:238–251. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery WP, Reise SP, Yu J. An empirical comparison of acculturation models. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1035–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Kiang L, Witkow MR, Baldelomar O. Stability and change in ethnic labeling among adolescents from Asian and Latin American immigrant families. Child Development. 2008;79:944–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández MM, Conger RD, Robins RW, Bacher KB, Widaman KF. Cultural socialization and ethnic pride among Mexican-origin adolescents during the transition to middle school. Child Development. 2014;85:695–708. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q-L, Nguyen AMD, Benet-Martínez V. Bicultural identity integration. In: Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, Vignoles VL, editors. Handbook of identity theory and research. Vol. 2. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 827–842. [Google Scholar]

- John A, Montgomery D. Socialization goals of first-generation immigrant Indian parents: A Q-methodological study. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2012;3:299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. The measurement of nonindependence. In: Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL, editors. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Perreira K, Fuligni A. Ethnic label use in adolescents from traditional and non-traditional immigrant communities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:719–729. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9597-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Chen Q, Li J, Huang X, Moon UJ. Parent-child acculturation, parenting, and adolescent depressive symptoms in Chinese immigrant families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:426–437. doi: 10.1037/a0016019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Gonzales NA, Stroh K, Wang JJL. Parent-child cultural marginalization and depressive symptoms in Asian American family members. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Shen Y, Huang X, Wang Y, Orozco-Lapray D. Chinese American parents’ acculturation and enculturation, bicultural management difficulty, depressive symptoms, and parenting. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2014;5:298–306. doi: 10.1037/a0035929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Wang Y, Chen Q, Shen Y, Hou Y. Parent-child acculturation profiles as predictors of Chinese American adolescents’ academic trajectories. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;44:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0131-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Wang Y, Orozco-Lapray D, Shen Y, Murtuza M. Does “tiger parenting” exist? Parenting profiles of Chinese Americans and adolescent developmental outcomes. Asian American Journal of psychology. 2013;4:7–18. doi: 10.1037/a0030612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber E, Nihira K, Mink IT. Filial piety, modernization, and the challenges of raising children for Chinese immigrants: Quantitative and qualitative evidence. Ethos. 2004;32:324–347. [Google Scholar]

- Lim S-L, Yeh M, Liang J, Lau AS, McCabe K. Acculturation gap, intergenerational conflict, parenting style, and youth distress in immigrant Chinese American families. Marriage & Family Review. 2008;45:84–106. [Google Scholar]

- Liu LL, Lau AS, Chen AC-C, Dinh KT, Kim SY. The influence of maternal acculturation, neighborhood disadvantage, and parenting on Chinese American adolescents’ conduct problems: Testing the segmented assimilation hypothesis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:691–702. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9275-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998 – 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A-MD, Benet-Martínez V. Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2013;44:122–159. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette D. Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development. 2004;47:193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, Caughy MO, Schuster MA, Bogart LM, Dittus PJ, Franzini L. Cultural orientations, parental beliefs and practices, and Latino Adolescents’ autonomy and independence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;43:1389–1403. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9977-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roest A, Dubas JS, Gerris JR. Value transmissions between parents and children: Gender and developmental phase as transmission belts. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Alden LE, Paulhus DL. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:49–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönpflug U. Intergenerational transmission of values: The role of transmission belts. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2001;32:174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Daddis C. Longitudinal development of family decision making: Defining healthy behavioral autonomy for middle-class African American adolescents. Child Development. 2004;75:1418–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su TF, Costigan CL. The development of children’s ethnic identity in immigrant Chinese families in Canada: The role of parenting practices and children’s perceptions of parental family obligation expectations. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:638–663. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, Seaton E. Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development. 2014;85:21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Zeiders KH, Updegraff KA. Family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity: a family-driven, youth-driven, or reciprocal process? Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:137–146. doi: 10.1037/a0031105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umañ-Taylor AJ, Alfaro EC, Bámaca MY, Guimond AB. The central role of familial ethnic socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Uttal L. Taiwanese immigrant mothers’ childcare preferences: socialization for bicultural competency. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:437–443. doi: 10.1037/a0025435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh W, Iedema J, Meuss W. The emerging gender gap: Cultural and economic conservatism in the Netherlands 1970-1992. Political Psychology. 1999;20:291–321. [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh WA, Iedema J, Raaijmakers QA. Intergenerational transmission and the formation of cultural orientations in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1185–1198. [Google Scholar]

- White RB, Zeiders K, Knight G, Roosa M, Tein J-Y. Mexican origin youths’ trajectories of perceived peer discrimination from middle childhood to adolescence: Variation by neighborhood ethnic concentration. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:1700–1714. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0098-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia YR, Do KA, Xie X. The adjustment of Asian American families to the US context: The ecology of strengths and stress. In: Peterson GW, Bush KR, editors. Handbook of Marriage and the Family. 3rd. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 705–722. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiders KH, Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, McHale SM, Padilla J. Familism values, family time, and Mexican-origin young adults’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jomf.12248. early view online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Chinatown: The socioeconomic potential of an urban enclave. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]