Abstract

We investigated 24-hour hemodynamic changes produced by salt loading and depletion in eight salt-sensitive (SS) and 13 salt-resistant (SR) normotensive volunteers. After salt loading, mean arterial pressure (MAP) was higher in SS (96.5±2.8) than SR (84.2±2.7 mmHg), p<0.01, owing to higher total peripheral resistance (TPR) in SS (1791±148) than SR (1549±66 dyn.cm−5.sec−1), p=0.05, whereas cardiac output (CO) was not different between groups (SS 4.5±0.3 vs SR 4.4±0.2 l/min, ns). Following salt depletion, CO was equally reduced in both groups. TPR increased 24±6% (p<0.001) in SR, whose MAP remained unchanged. In contrast, TPR did not change in SS (1±6%, ns). Thus, their MAP was reduced, abolishing the MAP difference between groups. SS had higher E/e’ ratios than SR in both phases of the protocol. In these 21 subjects and in 32 hypertensive patients, Na+ balance was similar in SR and SS during salt loading or depletion. However, SR did not gain weight during salt retention (−158±250 g), whereas SS did (819±204), commensurate to isoosmolar water retention. During salt depletion, SR lost the expected amount of weight for isoosmolar Na+ excretion, whereas SS lost a greater amount that failed to fully correct the fluid retention from the previous day. We conclude that SS are unable to modulate TPR in response to salt depletion, mirroring their inability to vasodilate in response to salt loading. We suggest that differences in water balance between SS and SR indicate differences in salt-and-water storage in the interstitial compartment that may relate to vascular dysfunction in SS.

Keywords: Salt sensitivity, Blood pressure, Hemodynamics, Sodium, Body water

Salt sensitivity (SS) of blood pressure (BP) is a trait observed in humans and animals, characterized by BP increases following salt loading and BP decreases following salt depletion. SS normotensive or hypertensive humans have a poorer prognosis than their salt resistant (SR) counterparts.1,2 Thus, SS is a cardiovascular risk factor, independent of BP. SS affects about one quarter of the normotensive adult population and more than half of all hypertensive patients.3 The prevailing viewpoint is that the increase in BP produced by salt loading in SS is a compensatory response to maintain salt balance via pressure natriuresis, owing to an underlying defect in one or more physiological natriuretic systems. This interpretation would explain the non-parallel, rightward-tilted shift in pressure-natriuresis curves observed in SS models of hypertension. However, despite the fact that genetic and physiological research has unraveled multiple possible natriuretic defects in SS, the possibility that the shift in pressure-natriuresis depends on defective renal sodium (Na+) excretion has not been proved with certainty. Other mechanisms could also account for a pressor effect of salt.

In contrast to the extensive research on alterations in natriuretic systems, the mechanism by which they might lead to an increase in BP remains obscure. An intuitive explanation would be that renal salt retention leads to plasma volume expansion, increasing preload and cardiac output (CO) and producing a hyperkinetic form of hypertension. However, studies of SS vs SR subjects have failed to show abnormally increased sodium retention or CO in the former. Actually, the hemodynamic pattern of SS hypertension is one of relative vasoconstriction, or impaired vasodilation in response to a normal salt-induced increase in CO.4-7 Therefore, the question of how increased salt intake translates into increased vascular smooth muscle contractility and higher total peripheral resistance (TPR) remains unanswered.

The concept of total-body autoregulation has been invoked as an explanation,8,9 although the original idea of Guyton et al pertained to adjustments in resistance in response to increases in local blood flow, not BP.10 According to this theory, increases in TPR may be the result of secondary adaptation to undetected increases in CO, occurring at stages earlier than the one at which the hemodynamic studies were conducted. The total-body autoregulation explanation was supported in an early study of young essential hypertensive patients who had initial increases in CO but transformed their hemodynamic pattern to one of increased TPR over a decade.11 However, if a decade must elapse before autoregulation is established, this explanation would not be applicable to the understanding of vasoconstriction of SS humans, which has been observed after giving a salt load over a few days to weeks4-7. Therefore, the first aim of our study was to determine whether or not different responses in TPR occur between SS and SR subjects in response to salt depletion over a 24-hour period. If so, the differences would constitute further evidence against the autoregulatory hypothesis.

Also, Na+ compartmentalization involves a component better studied in skin and striated muscle, in which Na+ is not stored iso-osmotically with water.12 An increase in accumulation of Na+ in skin and striated muscle has been associated with aging and hypertension.13 Hypothetically, altered accumulation of Na+ and water in the interstitium around vascular smooth muscle might directly affect contractility and explain rapid changes in TPR in SS subjects after a salt load. Therefore, the second aim of our study was to investigate differences between SS and SR subjects in terms of body weight, urine output, or Na+ excretion in responses to salt loading and salt depletion.

METHODS

Subjects and protocol

For the hemodynamic studies in the first aim of this project, we prospectively recruited 21 normotensive volunteers for an IRB-approved (Scott and White Hospital) protocol to assess their salt-sensitivity of blood-pressure (SSBP) and to obtain echocardiographic measurements of CO after salt loading and salt depletion. For the studies on body weight, salt, and water handling, we pooled the data of these 21 normotensive subjects with those of 32 hypertensive patients who had been previously studied with an identical IRB-approved protocol at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Subjects were classified as hypertensive if BP was higher than 140/90 mmHg or if they were receiving antihypertensive treatment. All subjects (normotensive and hypertensive) maintained their habitual salt intake for two weeks before study. Hypertensive patients discontinued all medications over this period, with monitoring of BP for safety. Medical histories with demographic and clinical characteristics, physical exams and routine laboratory data were obtained to assess for pre-specified exclusion criteria.

After about two weeks from the consent date, subjects were admitted to the research ward the night before starting the acute protocol for SSBP. This protocol was adapted from Grim et al14 as previously reported.15 Briefly, after awakening and ambulating at 6:00 am and after obtaining all clinical and baseline laboratory data, subjects started an isocaloric 160 mEq Na/day diet (metabolic kitchen) at 8:00 am and were given 2 L of normal saline as an intravenous infusion from 8:00 am to 12:00 pm for a total 24-hour Na+ intake of 460 mEq (salt loading or HiNa day). After awakening the next morning at 6:00 am, all clinical and laboratory data representing the effect of salt loading were obtained. Starting at 8:00 am, salt depletion was initiated with an isocaloric 10 mEq Na/day diet and three oral 40 mg doses of furosemide given at about 8:00 am, 12:00 pm and 4:00 pm (LoNa day). The following morning, clinical and laboratory data representing the effect of salt depletion were obtained, before the subject was discharged from the hospital. During both diet periods, potassium intake was maintained constant at 70 mEq/day. Oral fluid intake was kept ad libitum and was not monitored throughout the study.

BP was recorded throughout the entire hospitalization with an ambulatory, automated, noninvasive oscillometric device (SpaceLabs 90207). Readings were every 15 minutes from 6:00 am to 10:00 pm and every 30 minutes overnight. Baseline BP was the average of all readings (7.2±0.4) obtained from awakening on HiNa until starting the saline infusion. BP of HiNa was the average of all readings (51.4±0.8) from 12:00 pm (after the end of the saline infusion) until 10:00 pm (time to retire to bed) and BP of LoNa was the average of all readings (35±0.8) from 12:00 pm (after the second dose of furosemide) until 10:00 pm (time to retire to bed). An average fall in systolic BP ≥ 10 mmHg from HiNa to LoNa was employed to classify a subject as SS.

Body weight at baseline, after salt loading and after salt depletion was measured with the patient in a hospital gown, at about 6-7 am, before breakfast and using the same scale. Laboratory data included blood counts, chemistries with electrolytes and creatinine, plasma renin activity, aldosterone and insulin (radioimmunoassay), and plasma catecholamines (radioenzymatic assay). Serum osmolality was calculated as BUN (mg/dl)/2.8 + glucose (mg/dl)/18 + serum Na+ (mEq/l)*2. Insulin sensitivity was calculated as the HOMA2-S index, using the HOMA2 Calculator v2.2 of the Diabetes Trials Unit, University of Oxford (www.dtu.ox.ac.uk).16

All urine specimens were collected on ice throughout the study and kept refrigerated. They were divided into a 24-hour sample for the HiNa day, a 12-hour sample for the period of furosemide-induced diuresis and a 12-hour sample starting 4 hours after the last dose of furosemide (salt-depleted state). Volumes for each period were recorded. Creatinine and electrolytes were measured in fresh aliquots obtained at the end of each period. No attempt was made to measure extra-renal (skin or fecal) Na+ losses but the research wards were climate controlled and no patient had gastrointestinal alterations during study. Net external balance of Na+ was calculated as the total (dietary and intravenous) intake minus the urinary output.

Echocardiographic measurements

Echocardiograms (GE Vivid I, GE Healthcare) in the normotensive subjects were obtained at approximately 5 pm (±4.7 min) on both, the HiNa and LoNa days. That is, they were conducted 5 hours after finalizing the saline infusion on HiNa and one hour after the final dose of furosemide on LoNa. All subjects were in normal sinus rhythm without ectopy during the study. A measurement of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) diameter was obtained in the parasternal long-axis view in systole for calculation of the LVOT area. The LVOT velocity time integral (VTI) was measured using pulsed wave Doppler in the LVOT at the level of the annulus, in the apical 5-chamber view. Stroke volume (SV) was calculated as LVOT area × LVOT VTI and CO as SV × heart rate. Three consecutive measurements were obtained and averaged in each study. These Doppler-based CO measurements correlate well with invasively measured CO.17 TPR was calculated as the mean arterial pressure (MAP, from the monitors, within 1.00±1.85 minutes of the echocardiographic measurements) divided by the CO. Measured parameters of LV filling included the peak early (E-wave), and late diastolic (A-wave) filling velocities of the mitral inflow in an apical view, the E/A ratio, the deceleration time of E velocity, and the ratio between E velocity and e’ (tissue Doppler e annular velocity ratio). They were assessed using pulsed-wave Doppler in the apical 4-chamber view, according to the American Society of Echocardiography’s guideline for evaluation of LV diastolic function.18 E-wave velocity primarily reflects the left atrium-LV pressure gradient during early diastole and depends on preload and LV relaxation, whereas the E/e’ ratio offers a good estimate of LV filling pressures.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between SS and SR groups were made with unpaired Student’s t tests. Differences between periods in the same subjects were analyzed with paired t tests. Correlation coefficients were calculated with Pearson’s method. All previous tests and single linear regression analyses were performed with JMP software (SAS Institute). A probability less than 5% was used to reject the null hypothesis.

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1, comparing SS vs SR subgroups within normotensive and within hypertensive subjects, as well as between all SS and SR subjects analyzed together. The distribution of normotensive versus hypertensive subjects and females versus males was not different between the total SS and SR groups. Eight of 21 normotensive subjects (38%) and 16 of 32 hypertensive patients (50%) were SS. SS subjects were older, with a larger percentage of black subjects, higher BPs, increased aldosterone to renin ratios, and lower insulin sensitivity than their SR counterparts (particularly in normotensive subjects). All of these findings are consistent with usual features of the SS state. Plasma renin activity was somewhat lower and body-mass index (BMI) somewhat higher in SS than in SR; however, these differences did not reach statistical significance. The higher baseline BPs of all SS subjects were not only due to a slightly higher percentage of hypertensive patients in this group compared to SR, but also to a higher BP in normotensive SS, compared to normotensive SR. The average BP fall from the salt replete to the salt depleted state was significantly greater in SS than SR, as expected from the cutoff employed for classification of these two groups. Nonetheless, these responses were normally distributed in the entire population, as described in other studies.3

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and biochemical characteristics of the subjects

| Normotensive | Hypertensive | All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | SR (n=13) | SS (n=8) | SR (n=16) | SS (n=16) | SR (n=29) | SS (n=24) |

| Age (years) | 38 ± 3 | 41 ± 3 | 46 ± 2 | 47 ± 1 | 41 ± 2 † | 46 ± 1 |

| Gender, F/M (%/%) | 12/1(92/8) | 6/2(75/25) | 11/5(69/31) | 13/3(81/19) | 23/6 (79/21) | 19/5 (79/21) |

| Race, B/W (%/%) | 1/12(8/92) | 2/6(25/75) | 6/10 (37/63) | 12/4 (75/25) | 7/22 (24/76) ‡ | 14/10 (58/42) |

| SBP mmHg | 112 ± 3 § | 125 ± 3 | 150 ± 6 | 158 ± 5 | 133 ± 5 † | 147 ± 5 |

| DBP mmHg | 72 ± 2 § | 83 ± 2 | 92 ± 3 | 96 ± 3 | 83 ± 3 † | 92 ± 2 |

| ΔSBP (LoNa-HiNa) mmHg | −2.3 ± 1.1 ∥ | −13.7 ± 1.6 | −3.7 ± 1.1 ∥ | −14.4 ± 1.1 | −3.0 ± 0.8 ∥ | −14.2 ± 0.9 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 29.0 ± 1.6 * | 35.8 ± 3.6 | 34.2 ± 1.6 | 34.8 ± 2.2 | 31.8 ± 1.2 | 35.1 ± 1.8 |

| ClCr (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 148 ± 13 | 129 ± 12 | 116 ± 7 | 112 ± 7 | 131 ± 8 | 118 ± 6 |

| PRA (ngAI/ml/hr) | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 * | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| Aldo (ng/dl) | 10 ± 1 * | 8 ± 1 | 23 ± 3 | 20 ± 3 | 17 ± 2 | 16 ± 2 |

| Aldo/Renin ratio | 13 ± 3 | 19 ± 7 | 23 ± 4 † | 37 ± 6 | 18 ± 3 † | 31 ± 5 |

| Plasma catecholamines (pg/ml) | 395 ± 75 | 252 ± 23 | 386 ± 37 | 377 ± 58 | 390 ± 39 | 333 ± 39 |

| HOMA2-S (%) | 110 ± 16 § | 49 ± 7 | 28 ± 3 | 31 ± 3 | 66 ± 11 ‡ | 38 ± 4 |

SR, salt resistant; SS, salt sensitive; F, female; M, male; B, black; W, white, SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ΔSBP (LoNa-HiNa), decrease in blood pressure from the high-salt to the low-salt day; BMI, body mass index; ClCr, creatinine clearance; PRA, plasma renin activity; Aldo, plasma aldosterone; HOMA2-S, insulin sensitivity index. p-values for the comparison of SR vs SS within each subgroup and in all patients analyzed together:

>0.05<0.10;

<0.05;

<0.02;

<0.005;

<0.0001.

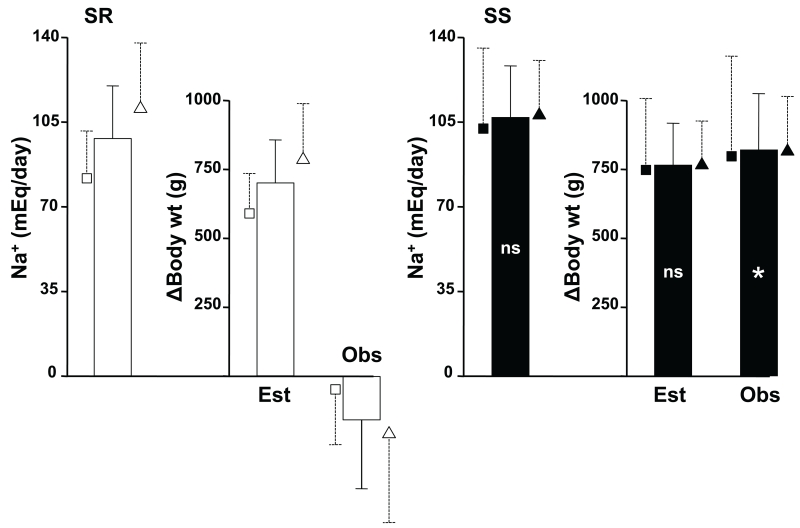

The left bars of Figure 1 show the amount of Na+ retained by SR and SS subjects during the 24 hours of salt loading (i.e., 460 mEq of Na+ intake minus the Na+ excreted in the 24-hour urine specimen). The middle bars show the calculated theoretical amount of weight that the subjects should have gained if they would have retained an iso-osmolar amount of water (calculated as Na+ retained / serum Na+ * 1000). The right bars show the actual change of body weight from baseline to the morning after salt loading was completed. In the left panel, we show that SR subjects retained 98±22 mEq Na+, predicting a weight gain of 697±157 g. However, the observed body weight change was −158±250 g, indicating that the entire amount of Na+ retained was somehow stored without accompanying water. The small symbols next to the bars show that this pattern of Na+ retention without concomitant weight gain was observed in both, normotensive and hypertensive SR subjects.

Fig 1.

The columns show data in all SR (white fill) or SS (black fill) subjects analyzed together. The small symbols with dashed error lines that surround each column show the same data in the respective normotensive (squares) or hypertensive (triangles) subgroups of each group. The leftmost columns of both panels shows the amount of sodium retained during the sodium loading day of the experiment (see text). The middle columns show the estimated (Est) amount of weight gain to retain the sodium in isoosmolar manner. The right columns show the actual observed (Obs) weight change in the two groups of patients. Symbols inside the black columns are for the difference for each parameter between the SS and SR groups. ns, not significant; *, p<0.001.

The right panel shows that the Na+ retention of SS subjects was 107±21 mEq, not significantly different from that of SR. This finding predicted a weight gain of 762±151 g. In contrast to SR, the actual body weight gain was 819±204 g, indicating that SS retained an iso-osmolar amount of water approximately concomitant to their Na+ retention, with a similar pattern in normotensive and hypertensive SS subjects. Consistent with this observation, SS subjects sustained a decrease in calculated serum osmolality (−1.7±0.9 mOsm/L, p<0.03), not observed in SR (+0.05±0.9, ns), not shown.

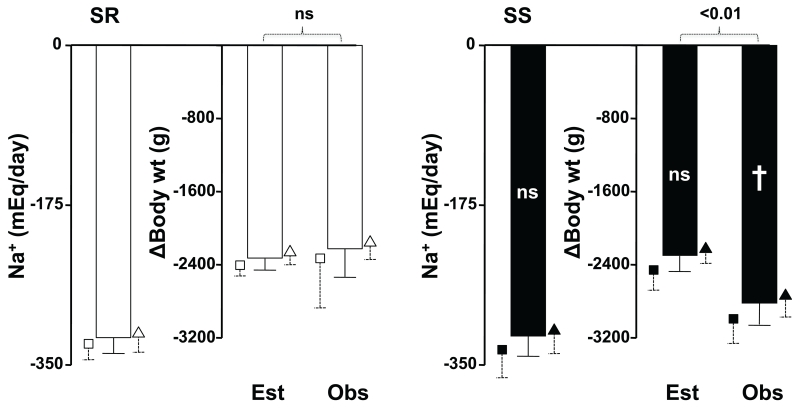

The left bars of Figure 2 show the amount of Na+ lost by SR and SS subjects during the 24 hours of salt depletion (i.e., 10 mEq of Na+ intake minus the Na+ excreted in the 24-hour urine). The middle bars show the calculated theoretical amount of weight that the subjects should have lost if they would have excreted an isoosmolar amount of water (Na+ lost / serum Na+ * 1000). The right bars show the actual body weight change from the salt replete to the salt depleted mornings. In the left panel, we show that SR subjects lost 320±17 mEq Na+, predicting a weight loss of −2327±121 g. The observed body weight loss was −2222±311 g, not significantly different from expected. Again, the small symbols show that this pattern occurred in both, normotensive and hypertensive SR subjects. Hence, despite the fact that SR subjects had retained Na+ without accompanying water, they lost an approximately isoosmolar amount of water when salt depletion was induced by diet and furosemide treatment.

Fig 2.

The columns show data in all SR (white fill) or SS (black fill) subjects analyzed together. The small symbols with dashed error lines that surround each column show the same data in the respective normotensive (squares) or hypertensive (triangles) subgroups of each group. The leftmost columns of both panels shows the amount of sodium lost during the sodium depleting day of the experiment (see text). The middle columns show the estimated (Est) amount of weight loss needed to lose the sodium with isoosmolar water. The right columns show the actual observed (Obs) weight change in the two groups of patients. Symbols inside the black columns are for the difference for each parameter between the SS and SR groups. ns, not significant; †, p~0.06. Brackets are for the comparison of expected vs actual weight loss in the SR and in the SS subjects.

The right panel shows that the Na+ loss of SS subjects was 318±22 mEq, not significantly different from that of SR and predicting a weight loss of 2300±162 g. The actual body weight loss was 2820±227 g, that is, greater (borderline statistical significance) than that of SR and significantly greater (by 519±203 g, p<0.01) than expected. This actual weight loss in excess of predicted weight loss represented only 63.5% of the weight gain produced by salt loading. This pattern of Na+ excretion in excess of that expected, but not sufficient to reverse the weight gain of the previous day, was observed in both normotensive and hypertensive SS subjects, as illustrated by the small symbols. Taken together, the data in Figures 1 and 2 suggest that whereas SR subjects were able to store Na+ without isoosmolar water when given a salt load, SS subjects were unable to do so and retained water commensurate to their Na+ retention. This water retention of SS was not fully corrected when they were subjected to salt depletion by a low salt intake and furosemide.

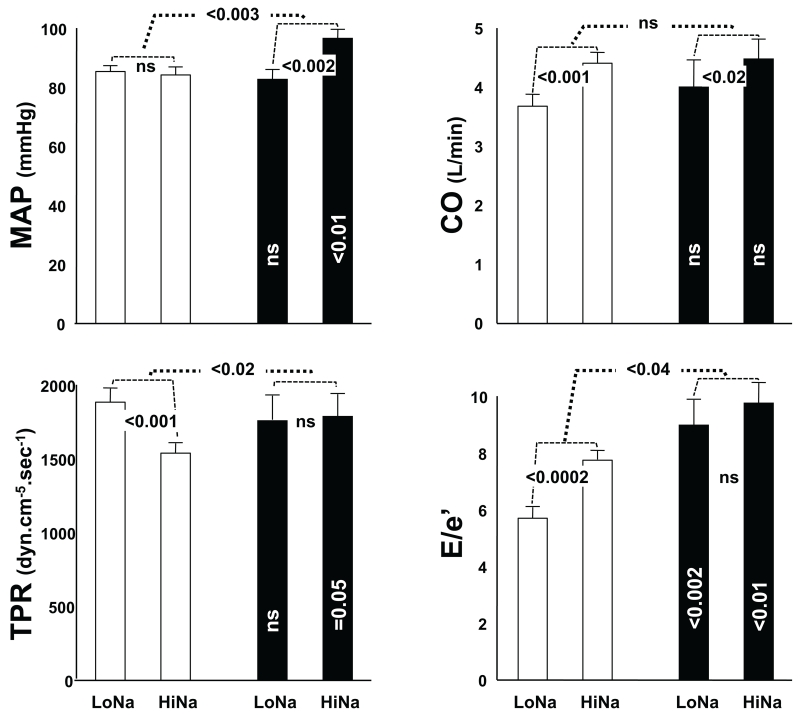

Results of the echocardiographic hemodynamic studies in 21 normotensive volunteers are given in Figure 3. The data on the second (salt-depletion) day of the experiment are presented first (the left of each pair of bars) to emphasize the observations that hemodynamics (MAP, CO and TPR) were not different between SR and SS subjects during Na+ depletion. The left top panel shows that whereas MAP of SR was not significantly different between LoNa (85.4±1.8 mmHg) and HiNa (84.2±2.7), Δ −1.2±2.9, ns, that of SS was significantly higher on HiNa (96.5±2.8) than on LoNa (82.6±3.3), Δ 13.9±3.0, p<0.001, as expected from their classification into the SR and SS subgroups. As a consequence of this, on the HiNa day, MAP of SS was significantly higher than that of SR, p<0.01.

Fig 3.

Hemodynamic parameters in 13 salt resistant (SR, open columns) and 8 salt sensitive (SS, black columns) normotensive volunteers. Data after the second day of the experiment are presented first, to emphasize that there were no hemodynamic differences between the groups after salt depletion. MAP, mean arterial pressure at the time of the echocardiograms; CO, cardiac output; TPR, total peripheral resistance; E/e’, the ratio between the E velocity of mitral inflow and the tissue Doppler e annular velocity; LoNa, the day of salt depletion; HiNa, the day of salt loading. Statistics given within the black columns are for the comparison of each parameter between SS and SR on the same day. Statistics given in the small brackets between columns are for the paired deltas of the parameters between LoNa and HiNa days, either within the SR or within the SS groups. Statistics given in the large brackets between pairs of columns are for the unpaired differences between the deltas in the SR and SS groups. ns, not significant.

The top right panel shows that CO was higher during HiNa than LoNa in both groups; SR 4.4±0.2 l/min vs 3.7±0.2, Δ 0.7±0.2, p<0.001, and SS 4.5±0.3 vs 4.0±0.5, Δ 0.5±0.2, p<0.02. Neither the absolute COs during LoNa or HiNa, nor the magnitude of the deltas between these two days was significantly different between SR and SS subjects. Higher COs during HiNa were a reflection of changes in SV, since heart rates were actually lower during HiNa than LoNa in both groups (SR 68±2 beats per minute vs 75±2, Δ −6.5±1.8, p<0.001, and SS 68±2 vs 78±3, Δ −10.6±3.3, p<0.001), not shown. Therefore, calculated TPR (bottom left panel) was lower in SR during HiNa (1549±66 dyn.cm−5.sec−1) than LoNa (1896±92), Δ −347±84, p<0.001, whereas it was not different between the two days in SS (1791±148 vs 1767±163, Δ 24±76, ns). As a consequence of this, during HiNa, TPR of SS was borderline higher than that of SR, p=0.05.

In contrast to the similar hemodynamics between SR and SS during LoNa, left ventricular filling pressures (E/e’ ratio, bottom right panel) were higher in SS than in SR on both days of the experiment (LoNa 9.0±0.9 vs 5.7±0.4, p<0.002, and HiNa 9.8±0.7 vs 7.7±0.3, p<0.01). These filling pressures were higher during HiNa than LoNa Δ 2.5±0.8, p<0.002 in SR, whereas in SS the overall higher E/e’ ratios were not different between the two days, Δ 0.8±0.6, ns. Two SS subjects had E/e’ ratios above 10 on the HiNa day, a value usually considered as the cutoff between normal and abnormal left ventricular filling. The E/A ratios were not significantly different between SS and SR subjects on either LoNa or HiNa. However, they were higher on HiNa than on LoNa in each group (SR 1.68±0.10 vs 1.22±0.07, Δ 0.48±0.13 p<0.001, and SS 1.40±0.08 vs 1.07±0.13, Δ 0.33±0.16, p<0.02), not shown.

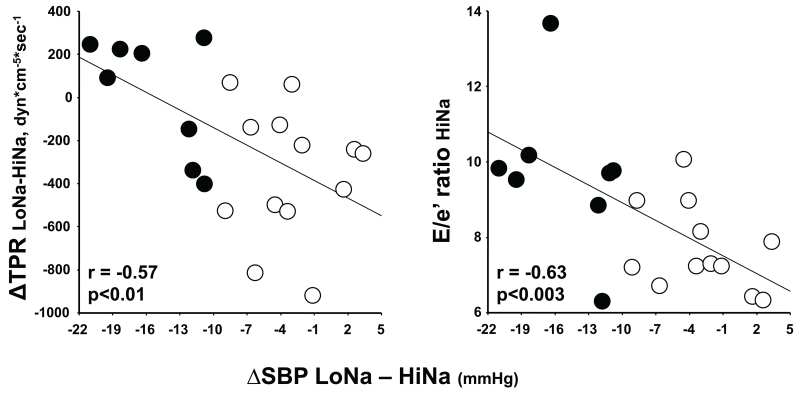

Figure 4 depicts significant relationships between the individual magnitude of SSBP in all subjects (delta systolic BP between LoNa and HiNa), the decrease in TPR between those two days (left panel) and the absolute E/e’ ratio on the HiNa day (right panel). As can be seen, the greater the degree of SS the lesser was the vasodilation during salt loading compared to salt depletion and the greater the left ventricular filling pressures when salt loaded. The respective regression equations were: ΔTPR(LoNa-HiNa) = −386.1 - 27.3 × ΔSBP(LoNa-HiNa) and E/e’HiNa = 7.501 - 0.157 × ΔSBP(LoNa-HiNa). Thus, for each mm Hg increase in SSBP there was a loss in the ability to vasodilate during a salt load of 27.3 dyn.cm−5.sec−1 of TPR and an increase in left ventricular filling pressures during salt loading of 0.157 units of E/e’ ratio. The relationship between SSBP and E/e’ ratio was also present on the LoNa day of the experiment (r=0.57, p<0.02, not shown).

Fig 4.

Relationships of the magnitude of SSBP; i.e., the difference in systolic BP between the low salt and high salt days of the experiment, (ΔSBP LoNa – HiNa, mmHg) with the change in TPR from LoNa to HiNa (left panel, ΔTPR LoNa-HiNa, dyn*cm-5*sec-1) or with the ratio between the E velocity of mitral inflow and the tissue Doppler e annular velocity on the HiNa day (right panel, E/e’ ratio HiNa). Black and white circles represent SS and SR subjects, respectively. Correlation coefficients, the regression lines and the statistical significance are for the 21 normotensive volunteers analyzed altogether.

DISCUSSION

The issue of how a salt load initiates an increase in BP in SS animals or humans has been a matter of great controversy. The total body autoregulatory theory proposes that due to an ill-defined deficit in salt excretion, salt retention leads to increases in plasma volume, cardiac preload, and an initially increased CO without significant change in TPR. Within this theoretical framework, later increases in TPR occur as an autoregulatory response to tissue hyperperfusion. Increased TPR maintains or exaggerates the BP elevation and resets CO back to normal, via pressure natriuresis. Three types of observations render support for this theory. First, young labile hypertensive subjects, whose early hemodynamic pattern was one of increased CO, converted such a pattern into one of normal CO and increased TPR a decade later.11 Second, most Mendelian forms of hypertension involve mechanisms that could initiate the cascade above by ostensibly causing renal Na+ retention.19 Third, dogs given aldosterone and salt developed hypertension mediated by increases in CO with initially unchanged TPR. These initial hemodynamic changes converted to a pattern of vasoconstriction over the course of 7-10 days.20 From these observations, investigators concluded that autoregulation of blood flow took place at the time the elevation of BP had reached a steady state.

However, we cannot exclude the possibility that changes in human hemodynamic patterns over a decade represent structural remodeling of the vasculature secondary to hypertension itself, rather than a functional change in vascular tone. Most Mendelian forms of hypertension are unquestionably linked to salt-transport mechanisms in the kidney. However, they have not been tested for SSBP with a formal protocol.21 In fact, a recently discovered Mendelian form of hypertension, studied with the same protocol applied here, has been ascribed to a sole increase in TPR, rather than to Na+ reabsorption.22 Furthermore, in the assumed salt-dependent forms of Mendelian hypertension, the possibility that the primary mechanism for salt-induced increases in BP might be extrarenal is not excluded, since many of the involved genes are ubiquitously expressed in vascular tissues, brain, and elsewhere. For example, expression of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells regulates endothelial function, vasoconstriction,23 and renal arteriolar myogenic responses.24 Therefore, renal hemodynamic changes could be responsible for BP responses to salt when this channel is mutated. Regarding the experiment in aldosterone-salt hypertensive dogs, the authors did not prove that “normal values” of TPR represented a “normal response” to salt, because there was no control group. Furthermore, neither in Mendelian forms of hypertension linked to Na+ transport, nor in aldosterone-salt hypertensive dogs, was there a direct investigation of how an increase in salt intake mediates the increase in BP.

In controlled experiments solely assessing the effect of salt, that is, without mineralocorticoid administration, it has been established that the normal vascular response to salt loading in SR animals or subjects was a significant vasodilation, not a “normal” TPR. This vasodilation allowed for maintenance of BP in the face of salt-induced increases in CO. In contrast, SS animals or subjects did not change TPR in response to salt. This seemingly “normal” TPR actually constituted the abnormality by which their BP increased, since the salt-induced increase in CO was not different from that of SR animals or subjects. These experimental observations were made in the Dahl strain of rats,25-27 even after avoiding volume expansion by servo-controlled feeding,28 and in dogs given high salt diets.29,30

Almost identical results were obtained in human studies. Sullivan et al first studied 10 young normal subjects who were given a 10 mEq/day Na+ diet for four days, followed by 4-6 days of a 200 mEq/day Na+ diet. They performed hemodynamic studies by echocardiography at the end of both periods and at 6 and 12 months later, when the subjects were on ad libitum diets containing 144±52 mEq Na/24 hours on average.5 BP remained at the baseline level throughout the year, whereas CO increased by 9% by the end of the high salt diet and by 33-34% at 6 months and 1 year, corresponding to 19% and 28-29% decreases in TPR. This observation was the first demonstration in humans that the normal hemodynamic adaptation to salt-induced increases in CO was a concomitant vasodilation for maintenance of normal BP. A few years later, the same group reported similar studies in 109 subjects, about half of whom were normotensive and half hypertensive. One third of the subjects were SS on the basis of their change in BP, when going from a 10 to a 200 mEq Na+/day diet both given for four days.4 The hemodynamic responses of SR subjects were similar to those of the normal young volunteers in the previous study. In contrast, SS subjects exhibited salt-induced increases in TPR, with or without concomitant increases in CO, suggesting an abnormal vascular response to salt. The latter was confirmed by demonstrating that SS subjects on high salt had increased forearm vascular resistance and decreased forearm blood flow compared to SR. Analogous results were obtained by Schmidlin et al.6 They studied 23 normotensive black subjects in whom repeated hemodynamic measurements were made by impedance cardiography during the last 3 days of a one week 30 mEq Na/day diet and during the 7 days of a 250 mEq Na+/day diet. They demonstrated that their SR and SS subjects did not differ in terms of their Na+ balance, plasma volume, or CO responses to high salt. Whereas BP remained normal in SR owing to vasodilation, it increased in SS owing to an inability to decrease TPR. In another study by the same investigators involving 37 normotensive blacks nearly equally distributed in SS and SR groups, they reproduced the earlier hemodynamic observations and showed that perhaps the inability of SS subjects to vasodilate in response to salt might be due to an abnormal salt-induced increase in asymmetrical dimethylarginine, not observed in SR.7

The hemodynamic results of our studies are entirely consistent with the view that salt-induced increases in BP are the result of abnormal vascular function in SS. However, there are four aspects of our study that are novel and important. First, the majority of our normotensive volunteers were white subjects. Thus, despite differences in the prevalence of SSBP between blacks and whites, the underlying hemodynamic mechanisms were indistinguishable. Second, because of our acute, in-patient protocol design, we actually assessed the hemodynamic effects of salt depletion, rather than that of salt loading as in the dietary studies above. Our SS subjects had higher BP than SR during salt loading, because their TPR values were higher and their CO measurements equal to those of their salt-loaded SR counterparts. Salt depletion led to a reduction in CO and increase in TPR in SR, with maintenance of a normal BP. In contrast, salt depletion did not change TPR in SS. Their BP values normalized due to the reduction in CO. Therefore, combined with the lack of normal vasodilation in response to salt, demonstrated in the dietary studies above, our data suggest that there is an impairment in the regulation of vascular tone in SS, in response to either salt loading or salt depletion. Third, we show that otherwise normal SS subjects have increased left ventricular filling pressures compared to SR, regardless of salt balance and not associated with differences in LV relaxation or preload (equal E/A ratios). This finding may indicate that concomitant to their vascular dysfunction, SS subjects exhibit early, subtle changes in myocardial contractility. Finally, perhaps the most striking feature of our studies is that the hemodynamic changes occurred within 24 hours (as opposed to days in the dietary studies) making it very unlikely that changes in TPR or the lack thereof can be attributed to total body autoregulation.

Higher but equal CO values in SS and SR after the salt load, compared to those after salt depletion, could theoretically be due to higher heart rates or SVs. In our subjects they were attributable to SV because heart rates were actually lower on the high than on the low salt day, an observation identical to that in normotensive blacks.6 Increases in SV may be due to increases in preload or cardiac contractility. Lower heart rates and equal levels of plasma catecholamines after salt loading in our study (not shown) make the latter possibility unlikely. In terms of preload, it is interesting that our balance studies show that SR subjects retained Na+ without water whereas SS ones retained concomitant water. If equal increases in CO by salt reflect equal increases in preload, it follows that the differential retention of salt and water in SS and SR did not differentially affect their effective intravascular volume. In the case of SR, the percent of total retained Na+ that remained in the intravascular compartment must have required a shift of water from the extravascular to the intravascular compartment, to maintain their normal osmolality after the salt load. In contrast, for the total Na+ and water retained by SS to produce an equal increase in preload to that in SR, there are two possible explanations. Either blood was pooled in a venous capacitance vascular bed, which is very unlikely since SS is characterized by increased sympathetic tone,31,32 or alternatively, some water must have shifted in the opposite direction. Overall, our data suggest that the differential retention of Na+ and water in SR and SS subjects must have differentially affected their storage in the interstitium.

We estimated Na+ balance from intake minus urinary excretion and the latter was in the range of 250-450 mEq on both days of the experiment (salt loading and furosemide effects). Under the conditions of our experiment (climate controlled hospital rooms, no gastrointestinal symptoms, no exercise), total skin, fecal and respiratory losses may have been in the 20-30 mEq/day range. Therefore, our results on Na+ balance could not have been significantly affected by extrarenal losses. Furthermore, we showed almost identical Na+ balances after salt loading and depletion in SR and SS subjects, which is consistent with observations by others.6

In contrast, we did not measure fluid intake. Therefore, we could not rely on urine volumes to make assumptions about water balance. The urine volumes were actually not different between SR and SS on either experimental day (not shown). We used 24-hour body weight changes as a surrogate because in such a short period and with isocaloric diets, weight changes most likely reflect acute changes in fluid balance, not in dry weights. It is from these data that we conclude that SS subjects retained more water than SR during salt loading and excreted less water than SR (compared to that retained during the salt load) during the period of salt depletion. Although based on a surrogate measure, this conclusion is consistent with previous observations with thorough measurements of fluid compartments and water balance (food content, fluid intake, urine and fecal water) in normal volunteers.33 In this study, large increases in salt intake from a habitual salt consumption (similar to the situation in our SR patients) did not change body mass and were associated with unexpected total body fluid losses. This is opposite to traditional beliefs on salt-induced water retention, derived from previous studies in subjects who were salt-depleted at baseline. Furthermore, these authors detected paradoxical increases in plasma volume despite lack of increase in extracellular fluid volume. They attributed this to shift of water towards the circulation, as we do for our findings in SR.

The reason for the apparent difference in water handling between SS and SR subjects cannot be ascertained from our studies. Theoretical possibilities include that SS have increased hypothalamic sensitivity to serum osmolality, reduced osmolar threshold for release of vasopressin, increased sensitivity of the renal tubular response to vasopressin or increased expression and activity of aquaporins. There is no information in humans about these topics. However, equal expression of the mRNA for the vasopressin type II receptor in the kidney of Dahl SS and SR rats,34 and markedly reduced expression of that for aquaporin-2 in a mouse model of renal dysgenesis with SS hypertension do not support these explanations.35

An intriguing possibility is raised by the recent characterization of sub-compartments of the interstitial space in which Na+ is stored without commensurate water accumulation. In mouse skin, regulation of the efflux of Na+ from such compartment involves hypertonicity-induced lymphangiogenesis. The latter is mediated by a pathway that begins with increased expression of the osmosensitive transcription factor tonicity enhancer binding protein (TonEBP) in skin interstitial macrophages. TonEBP increases macrophage production of VEGF-C, which activates the VEGF receptor 3 with ensuing lymphatic vessel proliferation.12 Interestingly, blockade of this pathway by a TonEBP-specific siRNA, by VEGF-C trapping with soluble VEGF receptor-3 or by macrophage depletion12,36 impairs lymphangiogenesis, thereby reducing lymphatic Na+ efflux and producing SS hypertension by mechanisms that may involve plasma endothelin-1.37 Conceivably, a reduced capacity for Na+ storage in this compartment might have led to obligatory isoosmolar water reabsorption during a salt load in our SS subjects. This idea is supported by the observation that Dahl rats actually have such reduced capacity for storage of osmotically inactive Na+.38 Finally, accumulation of water-free Na+ in striated muscle of humans, detected by magnetic resonance imaging techniques, is associated with aging and hypertension,13 which are both characterized by an increased prevalence of SSBP.

Other investigators have proposed that disturbed nitric oxide activity, aberrant sympathetic activation, or other pathways regulating TPR may underlie the impaired vasodilation exhibited by SS subjects after a salt load.7,39 We now propose that altered Na+ storage in SS individuals may play a role. Signaling between glycosaminoglycan-rich Na+ storage sites and the vasculature is not yet understood. However, there is emerging evidence that hyperosmolar Na+ activates and induces oxidative stress in dendritic cells with production of antigenice isoketal adducts that stimulate T-cell proliferation (Annet Kirabo DVM, MSc, PhD, personal communication), similar to observations in angiotensin and DOCA-salt hypertension.40 Thus, interstitial, hyperosmolar salt-induced vascular dysfunction may be due to the inflammatory state that has been implicated in the genesis of other forms of hypertension.

In conclusion, we provide supporting evidence for a major role of vascular dysfunction in SSBP. We also find that altered smooth muscle contractility may have a counterpart in altered cardiomyocyte contractility, affecting left ventricular filling pressures even in otherwise normal young individuals. Finally, we show that although Na+ handling does not differ between SR and SS subjects during salt loading or depletion (as shown previously by others), water handling does. Because our data suggest dissimilar storage of iso-osmolar versus hyperosmolar Na+ in the interstitium of SR and SS subjects and such storage has been linked to hypertension,13 we speculate that this difference may play a role in generating the SS state.

PERSPECTIVES

Salt sensitivity of blood pressure is a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in normotensive and hypertensive subjects (i.e., independent of blood pressure) that does not have a specific therapy because its ultimate mechanisms and causation are not fully understood. Opposite to a traditional view of this phenotype, based on putative abnormalities in Na+ retention, evidence has accumulated indicating that primary defects in vascular function may also play a role. Our data support this contention and allow for speculation about a link between such vascular dysfunction and abnormalities in interstitial sodium storage. This speculation requires proof in prospective studies of compartmentalized sodium storage in humans with and without the SS phenotype, which are now possible owing to emerging MRI-based techniques that directly detect Na+ in tissues.13 Unraveling of the mechanisms of salt sensitivity of blood pressure may facilitate development of targeted therapeutic interventions.

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What is new?

Abnormal vascular responses to salt deprivation occur in salt-sensitive normotensive subjects within 24 hours of the change in salt balance, supporting vascular dysfunction, as opposed to total body autoregulation, as the underlying mechanism.

Otherwise normal salt-sensitive subjects have subtle abnormalities in cardiomyocyte function leading to increased left ventricular filling pressures independent of the status of salt balance.

Balance data suggest that salt-resistant normotensive subjects exposed to a salt load store sodium without isoosmolar water in the interstitial fluid compartment; in contrast, salt-sensitive subjects retain the same amount of sodium during the salt load, but require isoosmolar water retention.

What is relevant?

The combination of the differential hemodynamics and differential sodium and water handling in salt-sensitive versus salt-resistant normotensive subjects supports the view that differential interstitial sodium storage relates to the vascular dysfunction of the former.

Summary

This study contributes to the body of knowledge supporting a role for vascular dysfunction in the salt-sensitive phenotype of humans, a cardiovascular risk factor without specific treatment. Unraveling of its mechanisms is required to allow for the development of therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by grant MO1 RR00073 NCRR and by the Scott, Sherwood, and Brindley Foundation

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Cheryl L Laffer: NONE

Robert C Scott III: NONE

Jens M Titze: NONE

Friedrich C. Luft: NONE

Fernando Elijovich: NONE

REFERENCES

- 1.Morimoto A, Uzu T, Fujii T, Nishimura M, Kuroda S, Nakamura S, Isenaga T, Kimura G. Sodium sensitivity and cardiovascular events in patients with essential hypertension. Lancet. 1997;350:1734–1737. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)05189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberger MH, Fineberg NS, Fineberg SE, Weinberger M. Salt sensitivity, pulse pressure, and death in normal and hypertensive humans. Hypertension. 2001;37:429–432. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinberger MH, Miller JZ, Luft FC, Grim CE, Fineberg NS. Definitions and characteristics of sodium sensitivity and blood pressure resistance. Hypertension. 1986;8:II127–II134. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.8.6_pt_2.ii127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan JM, Prewitt RL, Ratts TE, Josephs JA, Connor MJ. Hemodynamic characteristics of sodium-sensitive human subjects. Hypertension. 1987;9:398–406. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan JM, Ratts TE. Hemodynamic mechanisms of adaptation to chronic high sodium intake in normal humans. Hypertension. 1983;5:814–820. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.5.6.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidlin O, Forman A, Sebastian A, Curtis Morris RC., Jr. What initiates the pressor effect of salt in salt-sensitive humans? Hypertension. 2007;49:1032–1039. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.084640. R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidlin O, Forman A, Leone A, Sebastian A, Morris RC., Jr. Salt sensitivity in blacks: evidence that the initial pressor effect of NaCl involves inhibition of vasodilatation by asymmetrical dimethylarginine. Hypertension. 2011;58:380–385. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borst J, Borst-de Geus A. Hypertension explained by Starling’s theory of circulation homeostasis. Lancet. 1963;281:677–682. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)91443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ledingham JM, Cohen RD. Autoregulation of the total systemic circulation and its relation to control of cardiac output and arterial pressure. Lancet. 1963;281:887–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman TG, Granger HJ, Guyton AC. Whole-body circulatory autoregulation and hypertension. Circ Res. 1971;28:II76–II87. doi: 10.1161/01.res.28.5.ii-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund-Johansen P. Hemodynamic trends in untreated essential hypertension. Preliminary report on a 10 year follow-up study. Acta Medica Scandinavica-Suppl. 1976;602:68–76. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1977.tb07648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, Dahlmann A, Tammela T, Machura K, Park JK, Beck FX, Muller DN, Derer W, Goss J, Ziomber A, Dietsch P, Wagner H, van Rooijen N, Kurtz A, Hilgers KF, Alitalo K, Eckardt KU, Luft FC, Kerjaschki D, Titze J. Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med. 2009;15:545–552. doi: 10.1038/nm.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kopp C, Linz P, Dahlmann A, Hammon M, Jantsch J, Muller DN, Schmieder RE, Cavallaro A, Eckardt KU, Uder M, Luft FC, Titze J. 23Na magnetic resonance imaging-determined tissue sodium in healthy subjects and hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2013;61:635–640. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grim CE, Weinberger MH, Higgins JT, Kramer NJ. Diagnosis of secondary forms of hypertension. A comprehensive protocol. JAMA. 1977;237:1331–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laffer CL, Laniado-Schwartzman M, Wang MH, Nasjletti A, Elijovich F. Differential regulation of natriuresis by 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in human salt-sensitive versus salt-resistant hypertension. Circulation. 2003;107:574–578. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046269.52392.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2191–2192. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.12.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura RA, Callahan MJ, Schaff HV, Ilstrup DM, Miller FA, Tajik AJ. Noninvasive measurement of cardiac output by continuous wave Doppler echocardiography: initial experience and review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:484–489. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth OA, Waggoner AD, Flachskampf FA, Pellikka PA, Evangelista A. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiog. 2009;22:107–133. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell. 2001;104:545–556. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montani JP, Mizelle HL, Adair TH, Guyton AC. Regulation of cardiac output during aldosterone-induced hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl. 1989;7:S206–S207. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198900076-00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtz TW, Dominiczak AF, DiCarlo SE, Pravenec M, Morris RC., Jr. Molecular-based mechanisms of Mendelian forms of salt-dependent hypertension: questioning the prevailing theory. Hypertension. 2015;65:932–941. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maass PG, Aydin A, Luft FC, Schachterle C, Weise A, Stricker S, Lindschau C, Vaegler M, Qadri F, Toka HR, Schulz H, Krawitz PM, Parkhomchuk D, Hecht J, Hollfinger I, Wefeld-Neuenfeld Y, Bartels-Klein E, Muhl A, Kann M, Schuster H, Chitayat D, Bialer MG, Wienker TF, Ott J, Rittscher K, Liehr T, Jordan J, Plessis G, Tank J, Mai K, Naraghi R, Hodge R, Hopp M, Hattenbach LO, Busjahn A, Rauch A, Vandeput F, Gong M, Ruschendorf F, Hubner N, Haller H, Mundlos S, Bilginturan N, Movsesian MA, Klussmann E, Toka O, Bahring S. PDE3A mutations cause autosomal dominant hypertension with brachydactyly. Nat Genet. 2015;47:647–653. doi: 10.1038/ng.3302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusche-Vihrog K, Tarjus A, Fels J, Jaisser F. The epithelial Na+ channel: a new player in the vasculature. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:143–148. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000441054.88962.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung WS, Weissman JL, Farley J, Drummond HA. Beta ENaC is required for whole cell mechanically gated currents in renal vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 2013;304:F1428–F1437. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00444.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene AS, Yu ZY, Roman RJ, Cowley AW., Jr. Role of blood volume expansion in Dahl rat model of hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:H508–H514. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.2.H508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganguli M, Tobian L, Iwai J. Cardiac output and peripheral resistance in strains of rats sensitive and resistant to NaCl hypertension. Hypertension. 1979;1:3–7. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.1.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simchon S, Manger WM, Carlin RD, Peeters LL, Rodriguez J, Batista D, Brown T, Merchant NB, Jan KM, Chien S. Salt-induced hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hemodynamics and renal responses. Hypertension. 1989;13:612–621. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi N, Rapp JP, Brand PH, Metting PJ, Britton SL. Body fluid expansion is not essential for salt-induced hypertension in SS/Jr rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R1392–R1400. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.5.R1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krieger JE, Liard JF, Cowley AW., Jr. Hemodynamics, fluid volume, and hormonal responses to chronic high-salt intake in dogs. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H1629–H1636. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.6.H1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeClue JW, Guyton AC, Cowley AW, Jr, Coleman TG, Norman RA, Jr, McCaa RE. Subpressor angiotensin infusion, renal sodium handling, and salt-induced hypertension in the dog. Circ Res. 1978;43:503–512. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campese VM, Romoff MS, Levitan D, Saglikes Y, Friedler RM, Massry SG. Abnormal relationship between sodium intake and sympathetic nervous system activity in salt-sensitive patients with essential hypertension. Kidney Int. 1982;21:371–378. doi: 10.1038/ki.1982.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campese VM, Karubian F, Chervu I, Parise M, Sarkies N, Bigazzi R. Pressor reactivity to norepinephrine and angiotensin in salt-sensitive hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1993;21:301–307. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heer M, Baisch F, Kropp J, Gerzer R, Drummer C. High dietary sodium chloride consumption may not induce body fluid retention in humans. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:F585–F595. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.4.F585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lighthall GK, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Identification of salt-sensitive genes in the kidneys of Dahl rats. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1487–1494. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000133719.94075.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison-Bernard LM, Dipp S, El-Dahr SS. Renal and blood pressure phenotype in 18-mo-old bradykinin B2R(−/−)CRD mice. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:R782–R790. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00133.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machnik A, Dahlmann A, Kopp C, Goss J, Wagner H, van Rooijen N, Eckardt KU, Muller DN, Park JK, Luft FC, Kerjaschki D, Titze J. Mononuclear phagocyte system depletion blocks interstitial tonicity-responsive enhanced binding protein/vascular endothelial growth factor C expression and induces salt-sensitive hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 2010;55:755–761. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.143339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lankhorst S, Severs D, Marko L, Rakova N, Titze J, Muller DN, Danser AH, van den Meiracker AH. Salt-sensitivity of angiogenesis inhibition-induced blood pressure rise: role of interstitial sodium accumulation. J Hypertens. 2015;33(Suppl1):e77. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Titze J, Krause H, Hecht H, Dietsch P, Rittweger J, Lang R, Kirsch KA, Hilgers KF. Reduced osmotically inactive Na storage capacity and hypertension in the Dahl model. Am J Physiol. 2002:F134–F141. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00323.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris RC, Jr, Schmidlin O, Sebastian A, Tanaka M, Kurtz TW. Vasodysfunction that involves renal vasodysfunction, not abnormally increased renal retention of sodium, accounts for the initiation of salt-induced hypertension. Circulation. 2016;133:881–893. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirabo A, Fontana V, de Faria AP, Loperena R, Galindo CL, Wu J, Bikineyeva AT, Dikalov S, Xiao L, Chen W, Saleh MA, Trott DW, Itani HA, Vinh A, Amarnath V, Amarnath K, Guzik TJ, Bernstein KE, Shen XZ, Shyr Y, Chen SC, Mernaugh RL, Laffer CL, Elijovich F, Davies SS, Moreno H, Madhur MS, Roberts J, 2nd, Harrison DG. DC isoketal-modified proteins activate T cells and promote hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4642–4656. doi: 10.1172/JCI74084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]