Abstract

Purpose

The rates of cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) implantations and cardiac ablation procedures are increasing worldwide. To date, the management of CIED lead thrombi in the periablation period remains undefined and key clinical management questions remained unanswered. We sought to describe the clinical course and management strategies of patients with a CIED lead thrombus detected in the periablative setting.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of all patients who underwent a cardiac ablation procedure at Mayo Clinic Rochester from 2000-2014. Patients were included in our study cohort if they had documented CIED lead thrombus noted on periablation imaging studies. Electronic medical records were reviewed to determine the overall management strategy, outcomes, and embolic complications in these patients.

Results

Our overall cohort included 1833 patients, with 27(1.4%) having both cardiac ablation procedures as well as CIED lead thrombus detected on imaging. Of these 27 patients, 21 were male (77%), and the mean age was 59.2 years. The mean duration of follow-up was 16.5 months (range; 3 days – 48.3 months). Anticoagulation was an effective therapeutic strategy, with 11/14 (78.6%) patients experiencing either resolution of the thrombus or reduction in size on re-imaging. For atrial fibrillation ablation, the most common management strategy was a deferment in ablation with initiation/intensification of anticoagulation medication. For ventricular tachycardia ablations, most procedures involved a modified approach with the use of a retrograde aortic approach to access the left ventricle. No patient had any documented embolic complications.

Conclusions

The incidence of lead thrombi in patients undergoing an ablation was small in our study cohort (1.4%). Anticoagulation and deferral of ablation represented successful management strategies for atrial fibrillation ablation. For patients undergoing ventricular tachycardia ablation, a modified approach using retrograde aortic access to the ventricle was successful. In patients who are not on warfarin anticoagulation at the time of thrombus detection, we recommend initiation of this medication, with a goal INR of 2-3. For patients on warfarin at the time of thrombus detection, we recommend an intensification of anticoagulation with a goal INR of 3.0.

Keywords: Lead thrombus, cardiovascular implantable electronic devices, cardiac ablation

Introduction

Over the last decade, rates of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIED) implantations are increasing worldwide.[1-7] With an aging population, increasing life expectancy, advancement in technology, and broadening of clinical indications for insertion of cardiac devices,[8, 9] this number is predicted to continue to rise. Paralleling the rise of device implantation is the number of patients undergoing cardiac ablation procedures.[10-13] As a consequence of expanded CIED indications and increasing use of catheter ablation to treat arrhythmias cardiologist will face more patients undergoing cardiac ablations with CIEDs.

There is minimal data examining the impact of CIED on ablation procedures, with some highlighted concerns relating to an increased risk for developing venous complications, especially thrombosis[14-16] and subsequent embolization.[17] It has been recently reported that mobile lead thrombosis is a frequent discovery, occurring in 30% of individuals undergoing ablations.[18] During an ablation access to either the left ventricle or left atrium is attempted by transseptal puncture. The identification of lead thrombi raises practical concerns due to the subsequent risk for stroke from embolization of lead thrombi through the iatrogenic patent foreman ovale (PFO).[19, 20] Therefore when a lead thrombosis is present there is much hesitancy in proceeding with transseptal puncture and ablation is often aborted.

Despite our ability to detect intracardiac device lead thrombus; the management of these in an ablative environment to date remains elusive. Many key questions remain unanswered: What happens to those that are noticed to have a lead thrombus? How are these individuals managed? Do they experience any embolic phenomena? What is their natural history? With a lack of clear guidance in the management of lead thrombus in an ablative environment, the aim of our study was to systematically review our experience with patients who had a mobile thrombus detected on a CIED lead by periablation imaging to define their clinical course and management.

Methods

Study Population

We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical record at Mayo Clinic Rochester from 1st January 2000- 31st December 2014 to identify those patients that had a detected lead thrombus noticed on periablation echocardiogram (either intracardiac (ICE), transesophageal(TEE) or transthoracic echocardiogram(TTE)). The chart was electronically searched for the key words “lead thrombus,” “lead mass,” “lead clot,” and “mobile echodensity.” Patients were included if they fulfilled the following criteria, 1) undergoing or planned cardiac ablation, 2) detection of lead thrombus on periablation imagining. To determine the incidence of the lead thrombus, we reviewed all ablations and determined CIED status at time of ablation through the use of a combination of diagnosis (CIED in situ) and billing codes (which address periprocedural CIED device adjustment and interrogation). Patient characteristic data was collected through examination of the patient electronic medical record. Device data was collected from the nearest device check before the ablation procedure. If the patient happened to undergo placement of either an atrial or ventricular lead at a different time, the age of the lead with the thrombus was calculated. Baseline echocardiographic data was collected from the closest echocardiogram to the ablation date.

Results

Baseline demographics

Twenty-seven patients with a CIED were discovered to have a lead thrombosis on periablative imaging (12 periablation TEE/TTE, 15 ICE) with a mean follow up of 16.5 months (range, 3 days – 48.3 months). Baseline demographic data is shown in Table 1. Patients were predominately male (21/27, 78%) with a mean age of 59.2 ± 14.1 years. Indication for the ablation was predominately atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia (both 48.1%). A majority of patients had atrial fibrillation at baseline (19/27, 70.3%). Cardiomyopathy was common (66.7%) with an average ejection fraction 45.8 ± 17.0 (ischemic cardiomyopathy the most common type). Table 2 summaries the device characteristics. ICD was the most common CIED (16/27, 59.3%), with average age of device 38 months and average age of leads 106.1 months. The mean right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) was 32.5 ±11.4 mmHg. Four patients had a documented patent foramen ovale determined by both bubble and Doppler evaluation.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics (n=27).

| Male, n (%) | 21 (78.0) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 59.2 (±14.1) |

| Reason for ablation, n (%) | |

| Atrial Tachycardia | 1 (0.03) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13 (48.1) |

| Ventricular Tachycardia | 13 (48.1) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 19 (70.3) |

| Paroxysmal | 6 (31.6) |

| Persistent | 13 (68.4) |

| Permanent | 0 (0) |

| Comorbidities, n(%) | |

| History of MI | 10 (37.0) |

| Diabetes | 13 (48.1) |

| HTN | 19 (70.4) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 17 (46.0) |

| History of thrombus in past | 3 (11.1) |

| DVT/PE | 2 (7.4) |

| Atrial | 1 (3.7) |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 18 (66.7) |

| Ischemic | 8 (44.4) |

| Non-ischemic | 5 (18.5) |

| HCM | 4 (14.8) |

| ARVC | 1 (3.7) |

| Anticoagulation at time of procedure | 15 |

| Warfarin | 13 |

| Other | 2 |

| INR at time of procedure, average (SD) | 1.7 (±0.5) |

| Echocardiographic data | |

| LVEF, % | 45.8 ± 17.0 |

| RVSP, mmHg (SD) | 32.5 (11.4) |

| Patent Foramen Ovale, n (%) | 4 (15) |

Table 2. Device characteristics.

| Device Type, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| ICD | 16 (59.3) |

| PPM | 9 (11.1) |

| CRT | 2 (7.4) |

| Age of device*†, months (min,max) | 38.0 (3.4, 94.0) |

| Number of devices implanted, average (SD) | 1 (±0.5) |

| Age of leads*† | 106.1 (3.4, 1345.0) |

| Number of leads per patient, n (SD) | 2 (±0.7) |

| Atrial lead only | 0 |

| Ventricular leads only | 5 (19%) |

| Atria and Ventricular leads | 20 (74%) |

| Atria, Ventricular and coronary sinus (CRT) | 2 (7%) |

Age taken from new implant date

n =26, one patient exclude as unware of ICD device implant dates

Incidence of lead thrombus

Based upon the review of our charts and review of periablation imaging performed, we identified that 1833 (18% of total ablations during the time period) ablations occurred on individuals with a CIED during the defined time period. The incidence of lead thrombus in patients with a CIED who underwent an ablation was determined to be 27/1833 (1.4%).

Detection and characteristics of thrombus

ICE was the superior imaging modality for detection of thrombus. Thrombus was not reported on routine TTE in 9 patients (but noticed on TEE and ICE), while both TTE and TEE did not visualize thrombus in 5 patients despite visualization with ICE. The lead thrombus was detected on the atrial lead in 10/27 cases and on the ventricular lead in 17/27 cases, with an average size of 16.1 mm × 8.4 mm.

Management of thrombus

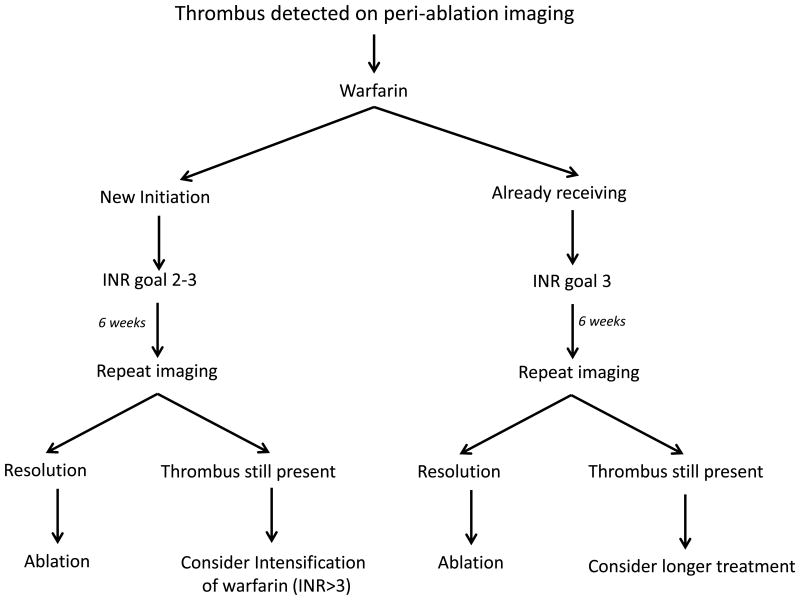

Figure 1 highlights the different management approaches and outcomes across our cohort. In those undergoing AF ablations the most common approach was to defer the ablation procedure, with very few proceeding. In those patients undergoing a VT ablation, thrombi inhibited the use of transseptal access and many required retrograde aortic access to access the left ventricle. Preceding the ablation 15 patients (55%) were receiving anticoagulation, 13 were on warfarin and 2 were on rivaroxaban. All patients received coagulation in our cohort post identification of the thrombus. Table 3 shows the impact of anticoagulation upon thrombus resolution. 11/14 (78.6%) patients experienced either resolution of the thrombus or reduction in size with the use of warfarin, either from initiation or intensification (defined as goal INR>3.0) of anticoagulation. In the 8 patients who experienced complete resolution of the thrombus, 6 were initiated on warfarin, and 2 underwent intensification. In those already on warfarin (n = 5), intensification to achieve a higher INR >3.0 was a successful strategy with 4/5 having either a reduction or resolution of the thrombus.

Figure 1. Impact of thrombus on cardiac ablation procedure.

Table 3. Impact of Anticoagulation on thrombus (n= 14*).

| Resolved | 8 (57.1) |

|---|---|

| On warfarin, n (%) | |

| Higher INR† | 2 (25%) |

| INR 2-3 | 0 |

| Initiated on warfarin, n (%) | |

| INR 2-3 | 6 (75%) |

| Reduction | 3 (21.4) |

| On warfarin, n (%) | |

| Higher INR† | 1 (33%) |

| INR 2-3 | 1 (33%) |

| Initiated on warfarin, n (%) | |

| INR 2-3 | 1 (33%) |

| No Change | 3 (21.4) |

| On warfarin, n (%) | |

| Higher INR† | 0 |

| INR 2-3 | 1 (33%) |

| Initiated on warfarin, n (%) | |

| INR 2-3 | 2 (66%) |

Excluding 13 patients (6 no repeat imaging, 7 TEE/ICE initially identified thrombus, repeat imaging was only TTE)

INR >3.0

Outcomes

Five patients who had resolved thrombus underwent repeat procedures with no complications at an average length to repeat procedure of 3.4 ± 1.9 months. No patient had documented embolic compilations related to lead thrombosis over the follow up period.

Discussion

CIED mobile thrombus is reported to occur in 30% of patients[18] undergoing an ablation procedure, however the management of these thrombi remains undefined. We are the first to report on long-term outcomes and management of CIED lead thrombus in patients undergoing a cardiac ablation. In this retrospective series, the incidence of lead thrombus is low (1.4%) and we highlight that the most common management approach in AF ablations was to defer the ablation with initiation or intensification of anticoagulation. In those undergoing VT ablation, modification of the procedure was performed with retrograde aortic access. These were largely successful strategies. Over our follow up period, clinical sequelae, in particular embolization from these thrombi were minimal.

We determined the incidence of lead thrombus to be 1.4% at our institution. Our data is similar to Rabher et al[21] who reported lead thrombus in 1.4% of their population who underwent a TTE. Our incidence is smaller when compared to Supple et al,[18] who reported thrombus at 30%. We hypothesize that our incidence is smaller because most of these imaging studies were not looking specifically for lead thrombus. Some thrombus is small and therefore may be difficult to detect unless one is specifically looking for it and there are added human factors such as operator experience, which could also limit thrombus detection. Supple et al, exclusively used ICE imaging, where we examined all imaging modalities.

In our cohort, the most common management strategy of CIED lead thrombus was to defer the ablation procedure with anticoagulation. This represents a successful approach with most patients (n=9, 64.3%) eventually having a repeat ablation or planning a repeat ablation in the near future. The concern with proceeding to ablation in those with CIED lead thrombus is transseptal access, which is frequently performed to access the left side of the heart during cardiac procedures. By performing transseptal access, an iatrogenic ASD is created and there is a risk that thrombi for the lead may dislodge and subsequently enter the left heart causing paradoxical embolization. Nevertheless, it has to be recognized that 2 patients proceeded with transeptal access despite the inherent risk. The actual risk of proceeding with transseptal puncture is not clearly defined and may also be a safe approach as these patients did not experience any adverse outcome. In both of these patients the decision to procedure was based upon clinical symptoms, with one patient having highly symptomatic atrial fibrillation and the other with incessant VT and concern for further deterioration in ventricular function and hemodynamic compromise. Although proceeded was not associated with any adverse outcome, given the potential devastating impact of an embolism should clinical circumstances allow, we would still recommend deferring the procedure with anticoagulation.

The impact of anticoagulation (warfarin) on thrombus in general is well acknowledged amongst the medical community. However, its role in the management of lead thrombus has not been reported in those undergoing a cardiac ablation. Our study confirms that anticoagulation is an effective management strategy to enable clot dissolution (table 3). Initiation of warfarin was successful in resolving and reducing thrombus in 8/10 patients (80%) while intensification of warfarin (n=5) to an INR of 3.0 was associated with resolution in two patients and reduction in one. In those patients on warfarin who did not undergo intensification, one experienced reduction and another no change in thrombus size. Based upon this data, we propose a two-pronged approach to anticoagulation (Figure 2). In those who are not on anticoagulation, initiation of warfarin with an INR of 2-3 will result in dissolution of the thrombus in a large majority of cases. In those already on warfarin, we recommend an intensification of warfarin to an INR 3.0, to enable thrombus resolution. The impact of warfarin on lead thrombi tells us mechanistically that these are likely to be truly thrombotic in nature and are not fibrotic. We hypothesis that those already on warfarin get benefit from intensification as they likely have a lack of time with a therapeutic INR[22, 23] (a significant issue, well recognized in patients taking warfarin). Therefore, initiation of a higher goal enables more time in the therapeutic window.

Figure 2. Flowchart highlighting the management of anticoagulation in periablative lead thrombus detection.

Our data supports the study by Rahbar et al,[21] where they showed that the initiation of intensified anticoagulation therapy resulted in reduction or shrinkage of thrombus in 9 of their patients whom they had follow up data on. The one major limitation of their study is that they only used TTE as the imaging modality. The concern regarding the sensitivity of TTE to identify thrombus is emphasized in our results, wherein a significant number of patients (n=5) did not have thrombus identified on regular TTE or TEE imaging but later diagnosed with ICE. Therefore, in their study it is unclear if those that were recorded as dissolved truly dissolved or simply shrunk in size and were not visible to repeat TTE. Supple et al[18] report similar data, it was noted that thrombus was not reported on any routine TTE in 26 patients who had detected mobile thrombus. This underlies the importance of ICE in the detection of lead thrombus. ICE is a relatively new addition to the electrophysiologists' armamentarium, and there is growing data showing it to have increased diagnostic accuracy in the diagnosis of CIED thrombus.[24]

In our cohort we did observe thrombus across a variety of devices and leads (Table 2). The most common device type in whom we detected thrombus was an ICD. The average age of the device was 38 months, with a mean lead age of 106 months. The average number of leads in our patients was 2, with most having both atria and ventricular leads. Ventricular leads were the most common site of thrombus. Given the small number of patients in our study, it is difficult to deduce any association between device/lead characteristics and risk of thrombus, future study of this could potentially help identify those patients at greatest risk.

Embolic phenomena from these thrombi are a major concern. However, no recorded embolic events occurred in our cohort. There is data to suggest that lead thrombus is associated with a significant increase in pulmonary artery pressure. Persistent thromboembolism from endocardial leads has been proposed as a potential mechanistic cause for this increase.[18] We did not find an increased RVSP among our patients with lead thrombus. Further evidence from a large study of 5646 CIED patients highlighted that the PE rate was low and suggests that it is possible that embolism of lead thrombus is uncommon or emboli are too small to cause consequential pulmonary infarction.[25] We would agree with these findings based upon our data.

While we are reporting on our experience with lead thrombus and show that anticoagulation represents a successful management approach, it is important to note a few limitations of this study. Its retrospective nature largely inhibits the ability to detect embolic phenomena from these thrombi as some may have had embolic events outside the Mayo Health System network. Further as we were only reporting on our experiences we have no comparison group in which thrombus was detected and anticoagulation was not given. In addition, the operators of the periablative imaging may not have been looking exclusively for lead thrombus and therefore lead thrombus may not have been specifically recorded, coded, or put in the ablation procedure report/note potentially leading to underreporting, which could have influence on the low incidence that we observed. Lastly, different imaging modalities on the follow up of the lead thrombus limited our ability to have larger numbers to determine the impact of anticoagulation. Further prospective studies are needed to truly determine the incidence of lead thrombus.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated in this retrospective study that the incidence of lead thrombi in patients undergoing an ablation is small at 1.4%. Initiation of anticoagulation and deferral of ablation represents a successful management strategy in those receiving an AF ablation. In those requiring left ventricular access for VT ablation retrograde aortic modification is a successful approach.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Dr. DeSimone is supported by a NIH Training Grant T32 #HL0070111

Footnotes

Conflict(s) of interest: None

References

- 1.Gadler F, Valzania C, Linde C. Current use of implantable electrical devices in Sweden: data from the Swedish pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registry. Europace. 2015;17(1):69–77. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voigt A, Shalaby A, Saba S. Continued rise in rates of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections in the United States: temporal trends and causative insights. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33(4):414–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uslan DZ, et al. Temporal trends in permanent pacemaker implantation: a population-based study. Am Heart J. 2008;155(5):896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhan C, et al. Cardiac device implantation in the United States from 1997 through 2004: a population-based analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(Suppl 1):13–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0392-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boriani G, et al. Implantable electrical devices for prevention of sudden cardiac death: data on implant rates from a ‘real world’ regional registry. Europace. 2010;12(9):1224–30. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Implementation of device therapy (cardiac resynchronization therapy and implantable cardioverter defibrillator) for patients with heart failure in Europe: changes from 2004 to 2008. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(12):1143–51. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raatikainen MJ, et al. Statistics on the use of cardiac electronic devices and electrophysiological procedures in the European Society of Cardiology countries: 2014 report from the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2015;17(Suppl 1):i1–i75. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein AE, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(3):e6–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Society of, C. et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Europace. 2013;15(8):1070–118. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, et al. Ten-year trends in the use of catheter ablation for treatment of atrial fibrillation vs. the use of coronary intervention for the treatment of ischaemic heart disease in Australia. Europace. 2013;15(12):1702–9. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kneeland PP, Fang MC. Trends in catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):E1–5. doi: 10.1002/jhm.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palaniswamy C, et al. Catheter ablation of postinfarction ventricular tachycardia: ten-year trends in utilization, in-hospital complications, and in-hospital mortality in the United States. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(11):2056–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz DF, et al. Safety of Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation in Clinical Practice: Findings from 9,699 Hospital Discharge Records. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spittell PC, Hayes DL. Venous complications after insertion of a transvenous pacemaker. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67(3):258–65. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitrovic V, et al. Thrombotic complications with pacemakers. Int J Cardiol. 1983;2(3-4):363–74. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(83)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoney WS, et al. The incidence of venous thrombosis following long-term transvenous pacing. Ann Thorac Surg. 1976;22(2):166–70. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)63980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prozan GB, et al. Pulmonary thromboembolism in the presence of an endocardiac pacing catheter. JAMA. 1968;206(7):1564–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Supple GE, et al. Mobile thrombus on device leads in patients undergoing ablation: identification, incidence, location, and association with increased pulmonary artery systolic pressure. Circulation. 2011;124(7):772–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.028647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeSimone CV, et al. Stroke or transient ischemic attack in patients with transvenous pacemaker or defibrillator and echocardiographically detected patent foramen ovale. Circulation. 2013;128(13):1433–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaidya VR, et al. Implanted endocardial lead characteristics and risk of stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2014;41(1):31–8. doi: 10.1007/s10840-014-9900-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahbar AS, et al. Risk factors and prognosis for clot formation on cardiac device leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36(10):1294–300. doi: 10.1111/pace.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker WL, et al. Meta-analysis to assess the quality of warfarin control in atrial fibrillation patients in the United States. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(3):244–52. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.3.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Walraven C, et al. Effect of study setting on anticoagulation control: a systematic review and metaregression. Chest. 2006;129(5):1155–66. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narducci ML, et al. Usefulness of intracardiac echocardiography for the diagnosis of cardiovascular implantable electronic device-related endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(13):1398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noheria A, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with transvenous cardiac implantable electronic device leads. Europace. 2015 doi: 10.1093/europace/euv038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]