Abstract

Background

Although bisphosphonate is effective for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, poor medication compliance is a key-limiting factor. We determined whether alarm clock could improve compliance with weekly bisphosphonate in patients with osteoporosis, by comparing with age- and gender-matched control group.

Methods

Fifty patients with osteoporosis were recruited and participated in alarm clock group. Patients were asked to take orally weekly risedronate for 1 year, and received alarm clock to inform the time of taking oral bisphosphonate weekly. Using the propensity score matching with age and gender, 50 patients were identified from patients with osteoporosis medication. We compared the compliance with bisphosphonate using medication possession ratio (MPR) between two groups.

Results

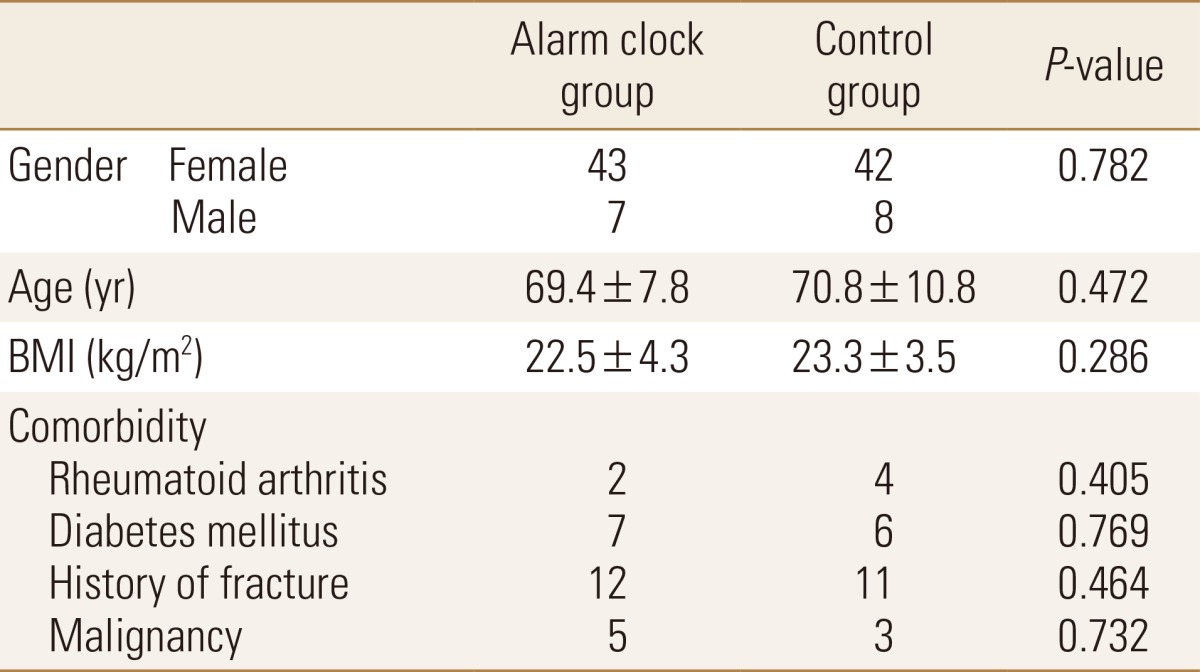

Although there was no significant difference of baseline characteristics between both groups, the mean MPR (0.80±0.33) of alarm clock group was higher than that (0.56±0.34) of control group (P<0.001).

Conclusions

Alarming could improve the compliance with weekly oral bisphosphonate in patients with osteoporosis.

Keywords: Bisphosphonate osteoporosis, Patient compliance

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture.[1,2,3,4]

Bisphosphonate is the most widely used drugs to prevent and treat osteoporosis.[5,6,7,8,9] Although bisphosphonate is effective for the treatment of osteoporosis and prevention of osteoporotic fractures, poor medication compliance is a key-limiting factor in terms of the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.[5,6,7,10,11] Bisphosphonate-related factors including gastroesophaseal irritation and complex method of ingestion have been well-known risk factors for low compliance with bisphosphonate.[12,13,14] To overcome poor compliance, new type of bisphosphonate with various dose intervals have introduced. Bisphosphonates with longer interval have shown better compliance.[15,16,17]

However, there have been few intervention studies on improving compliance with bisphosphonate. Our purpose was to determine whether alarm clock could improve compliance with weekly bisphosphonate in patients with osteoporosis, by comparing with age- and gender-matched control group without alarm clock.

METHODS

This is a case-control study conducted with prospectively complied data.

From May 2012 to May 2013, 50 patients with osteoporosis were recruited and participated in alarm clock group. The inclusion criteria were (1) 65 years of age and over, (2) diagnosis of osteoporosis (T-score below -2.5 standard deviation) based on the most recent bone mineral density (BMD) measurements (hip or spine, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry [DXA]), (3) without contraindications to oral bisphosphonate, (4) no cognitive impairment, and (4) ability of interview independently. All eligibility patients were asked to take orally weekly risedronate for 1 year, and received alarm clock to inform the time of taking oral bisphosphonate weekly (Fig. 1). Clocks were provided by Sanofi Aventis. In order to avoid selection bias, written informed consent was not required.

Fig. 1. Alarm clock will ring, when it reaches target day.

To obtain control group, the propensity score matching with age and gender was used. As control group, 50 patients, who had taken weekly oral risedronate for treatment of osteoporosis and were followed up for 12 months or more, were identified from patients with osteoporosis medication between 2005 and 2010. The medical records whom they had not received alarm clock in were reviewed to evaluate compliance with bisphosphonate.

To compare the compliance between two groups, we analyzed compliance with bisphosphonates during 12 months after first prescription. Compliance with bisphosphonates was measured a period of 1 year of treatment after first prescription by using medication possession ratio (MPR) as the parameter.[9,18] MPR was defined as the sum of days of supply of osteoporosis medications divided by the length of follow-up, i.e., 365 days. Compliance was categorized with MPR<80% and MPR≥80%.[18,19]

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards and Ethics Committee.

1. Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, student's t-test was used for continuous data and Pearson's chi-squared test for categorical data. All continuous data are expressed as means and standard deviations (SD). P-values<0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

There was no significant difference of baseline characteristics including age and gender between both groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of both groups.

BMI, body mass index.

The mean MPR (0.80±0.33) of alarm clock group was higher than that (0.56±0.34) of control group (P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates compliance with weekly oral bisphosphonate in patients alarmed with clock. This study presented that alarming could improve the compliance with weekly bisphosphonate in patients with osteoporosis.

Poor compliance is a major challenge in contemporary therapeutics, because osteoporosis has asymptomatic feature itself like other silent chronic diseases. Higher ages, low socioeconomic status, low awareness on osteoporosis, various interval of administration, and adverse effect of bisphosphonate have been presented to be risk factors for low compliance with bisphosphonate.[12,13,14] Identifying patients with high risk of low compliance and efforts to increase compliance are very important in treatment of osteoporosis.

Complex dosing schedules related to other chronic diseases, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus could lead to lack of compliance for osteoporosis medication. Simply forgetting to take the medication may also result in non-persistence or non-compliance in old ages.[20,21] In a previous study, 24% of the patients answered that they occasionally forgot to refill a prescription, as the reason why they did not fill prescriptions with drug regimens.[21] Therefore, it is important to alarm patients taking the medication, not to forget.

In this study, the MPR (0.56) of oral bisphosphonate without alarm clock is similar with that of another study.[22,23] However, weekly bisphosphonate with alarm clock could improve MPR (0.80) obviously in this study.

In this study, we used clock with alarming function. Currently, this intervention using alarming can be conducted with smartphone or message service using IT technology.

There are some limitations. First, we did not perform randomized study, but used historical control group. But, not to intervene control group will be ethical problem. Second, we included only patients with weekly oral bisphosphonate. Third, we did not evaluate the change of BMD and compare the incidence of osteoporotic fracture. Fourth, we did not calculate a sample size prior to study. But, power of this study was 94.5% with type 1 error of 5%.

This study, which is the first study to intervene for compliance with bisphosphonate, presented that alarming could improve the compliance with weekly bisphosphonate in patients with osteoporosis.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

We appreciated Sanofi Aventis providing alarm clocks.

References

- 1.Park C, Ha YC, Jang S, et al. The incidence and residual lifetime risk of osteoporosis-related fractures in Korea. J Bone Miner Metab. 2011;29:744–751. doi: 10.1007/s00774-011-0279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salaffi F, Cimmino MA, Malavolta N, et al. The burden of prevalent fractures on health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: the IMOF study. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1551–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon HK, Park C, Jang S, et al. Incidence and mortality following hip fracture in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:1087–1092. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.8.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haentjens P, Autier P, Collins J, et al. Colles fracture, spine fracture, and subsequent risk of hip fracture in men and women. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-a:1936–1943. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG, et al. Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med. 2009;122:S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadji P, Claus V, Ziller V, et al. GRAND: the German retrospective cohort analysis on compliance and persistence and the associated risk of fractures in osteoporotic women treated with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1535-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landfeldt E, Ström O, Robbins S, et al. Adherence to treatment of primary osteoporosis and its association to fractures--the Swedish Adherence Register Analysis (SARA) Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:433–443. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha YC, Lee YK, Lim YT, et al. Physicians' attitudes to contemporary issues on osteoporosis management in Korea. J Bone Metab. 2014;21:143–149. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2014.21.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soong YK, Tsai KS, Huang HY, et al. Risk of refracture associated with compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in Taiwan. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:511–521. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1984-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell RG, Watts NB, Ebetino FH, et al. Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: similarities and differences and their potential influence on clinical efficacy. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:733–759. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilezikian JP. Efficacy of bisphosphonates in reducing fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2009;122:S14–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamatari M, Koto S, Ozawa N, et al. Factors affecting long-term compliance of osteoporotic patients with bisphosphonate treatment and QOL assessment in actual practice: alendronate and risedronate. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:302–309. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0768-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kertes J, Dushenat M, Vesterman JL, et al. Factors contributing to compliance with osteoporosis medication. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weycker D, Macarios D, Edelsberg J, et al. Compliance with osteoporosis drug therapy and risk of fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:271–277. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0230-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, et al. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1453–1460. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YK, Nho JH, Ha YC, et al. Persistence with intravenous zoledronate in elderly patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:2329–2333. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, et al. A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1023–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold DT, Martin BC, Frytak JR, et al. A claims database analysis of persistence with alendronate therapy and fracture risk in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:585–594. doi: 10.1185/030079906X167615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1013–1022. doi: 10.4065/81.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman SL, Gold DT. Compliance and persistence with osteoporosis therapies. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:118–122. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman SL, Schousboe JT, Gold DT. Oral bisphosphonate compliance and persistence: a matter of choice? Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:21–26. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1274-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ziller V, Kostev K, Kyvernitakis I, et al. Persistence and compliance of medications used in the treatment of osteoporosis--analysis using a large scale, representative, longitudinal German database. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;50:315–322. doi: 10.5414/cp201632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziller V, Wetzel K, Kyvernitakis I, et al. Adherence and persistence in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with raloxifene. Climacteric. 2011;14:228–235. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.514628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]