Abstract

Peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL) is a heterogeneous group of aggressive lymphomas with poor prognosis. Elderly (age ≥ 65years) patients generally have impaired bone marrow function, altered drug metabolism, comorbidities, and poor functional status. Thus, treatment of elderly patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL remains a challenge for clinicians. A recent study disclosed that pralatrexate has a synergistic effect in combination with bortezomib. Weekly pralatrexate and bortezomib were administered intravenously for 3 weeks in a 4-week cycle. Of 5 patients, one achieved complete response after 4 cycles which has lasted 12 months until now. Another patient attained partial response after 2 cycles. Only 1 patient experienced grade 3 thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. Two patients suffered from grade 3 mucositis. Combination therapy with pralatrexate and bortezomib may be used as a salvage therapy for relapsed or refractory PTCL in the elderly with a favorable safety profile.

Keywords: Peripheral T Cell Lymphoma, Pralatrexate, Bortezomib, Elderly

Graphical Abstract

Peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL) is a heterogeneous group of aggressive lymphomas with a generally unfavorable prognosis (1,2). Although PTCL is sensitive to the conventional CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen, clinical outcomes have been uniformly disappointing with a poor overall response rate and shorter progression-free survival as compared to B cell lymphoma (3). Particularly, elderly patients generally have impaired bone marrow reserve, altered drug metabolism, multiple comorbidities, and poor performance status. They frequently show intolerance and treatment related-complications with full dose chemotherapy. Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration approved pralatrexate for treatment of relapsed or refractory PTCLs (4,5). Pralatrexate was designed for selective uptake and retention by malignant cells. It easily enters malignant cells with overexpression of folate membrane transporters and is efficiently polyglutamylated, which increases intracellular half-life. Owing to this unique nature, the agent has shown durable responses in highly refractory cases even after discontinuation (6,7). It has little cumulative toxicity and can be administered continuously to patients of old age or ineligible for consolidative stem cell transplantation. Bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor useful in other lymphoid malignancies including multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma (8). In addition, a recent report demonstrated that the combination of pralatrexate and bortezomib enhanced efficacy compared with that of either agent alone in vitro and in vivo models of T cell malignancy (9). Hence, we performed a pilot study that evaluated the response rate, duration of response, and safety profile of this combination regimen in elderly patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL.

In a single institution, five patients with refractory or relapsed PTCL who were aged more than 65 years were recruited from July 2013 to March 2015. Patients had several treatment-related toxicities after one or more conventional treatments at enrollment and agreed with this pilot trial. The median age was 73 years (range 67-77 years), and all patients had advanced-disease at diagnosis. Each patient had one or more comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, previous myocardial infarction, hypertension, or bone marrow hypoplasia. The PTCL subtypes were 2 PTCL-not otherwise specified (NOS), 2 angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and 1 NK/T-cell lymphoma (NK/TCL). The median number of prior systemic therapies were 3 (range 1-5 regimens including 1 autologous stem cell transplantation). Two patients were treated with methotrexate-based chemotherapy before recruitment (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Case | Age/Sex | PTCL subtype | ECOG PS | Stage | IPI | PIT | Prior systemic therapy | Prior MTX exposure | Comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67/M | PTCL-NOS | 1 | III | 3 | 2 | CHOEP, ICE, ASCT | No | Bone marrow hypoplasia |

| 2 | 74/M | AITL | 1 | III | 2 | 1 | CHOEP, ICE, SMILE, DHAP, MINE | Yes | Chronic kidney disease, Bone marrow hypoplasia |

| 3 | 73/M | NK/TCL | 1 | IV | 3 | 1 | VIDL | No | Hypertension |

| 4 | 77/M | AITL | 2 | IV | 5 | 3 | CHOP | No | Chronic kidney disease |

| 5 | 69/M | PTCL-NOS | 0 | III | 3 | 2 | CHOEP, ICE, SMILE, VIDL | Yes | COPD, Ischemic heart disease |

PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; NK/TCL, NK/T cell lymphoma ; ECOG PS , eastern cooperative oncology group performance status; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IPI, international prognostic index; PIT, prognostic index for T-cell lymphoma; MTX, methotrexate; CHOEP, cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + vincristine + prednisone + etoposide; ICE, ifosfamide + carboplatin + etoposide; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; SMILE, dexamethasone + methotrexate + ifosfamide + L-asparaginase + etoposide; DHAP, cisplatin + cytarabine + dexamethasone; MINE, mesna + ifofamide + mitoxantrone+etoposide; VIDL, etoposide+ifosfamide + dexamethasone + L-asparaginase.

The treatment schedule consisted of three weekly doses of intravenous 15 mg/m2 pralatrexate and 1.3 mg/m2 bortezomib with 1 week rest, repeated every 28-days. A total of four cycles of praltrexate and bortezomib (VP) regimen were planned if uneventful. Concomitant medication to alleviate mucositis included intramuscular injection of 1mg vitamin B12 within 7 days before initiation of every cycle and daily 45 mg of leucovorin during the entire period of treatment. The VP regimen was continued till progressive disease, intolerance, patient/physician discretion, or completion of regimen. Physical examinations and laboratory tests were performed during weekly visits and interim response was assessed at completion of the second cycle. Adverse events were evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events scale, version 4.0.

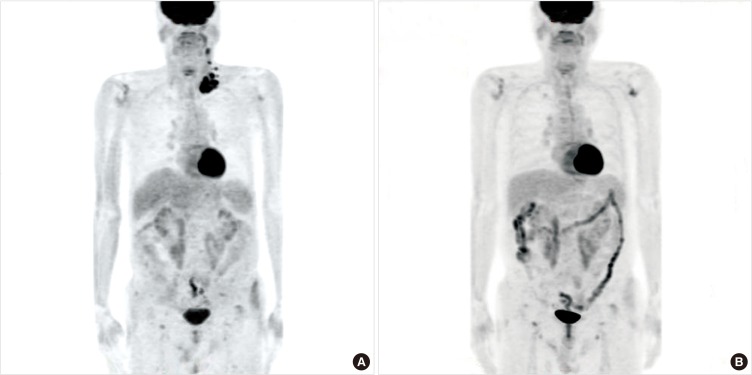

Two out of 5 patients responded to the combination therapy (Table 2). A 77-year old man with relapsed angioimmunoblatic T-cell lymphoma three months after 6 cycles of CHOP therapy attained partial response and complete response sequentially after 2 and 4 cycles of VP combination therapy, respectively. His palpable mass regressed at the end of the first cycle. He has been in complete response for about 12 months until now (Fig. 1). Of note, this patient was categorized into the unfavorable risk group according to Prognostic Index for PTCL (10). Another 67-year-old patient achieved partial response after 2 cycles, duration of which was 47 days. However, this patient discontinued the treatment after 3 cycles due to patient withdrawal. The disease progressed two months after discontinuation. Two patients died of disease progression and infection despite two cycles of treatment. The final patient was treated with only 1 cycle of treatment because of disease progression and was treated with other salvage therapy.

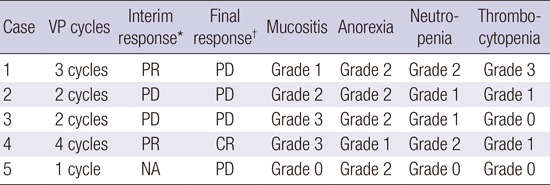

Table 2. Response to treatment and grades of major adverse events.

| Case | VP cycles | Interim response* | Final response† | Mucositis | Anorexia | Neutropenia | Thrombocytopenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 cycles | PR | PD | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 |

| 2 | 2 cycles | PD | PD | Grade 2 | Grade 2 | Grade 1 | Grade 1 |

| 3 | 2 cycles | PD | PD | Grade 3 | Grade 2 | Grade 1 | Grade 0 |

| 4 | 4 cycles | PR | CR | Grade 3 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 1 |

| 5 | 1 cycles | NA | PD | Grade 0 | Grade 2 | Grade 0 | Grade 0 |

VP, bortezomib + pralatrexate; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; PD, progressive disease; NA, not applicable.

*Interim response was determined by positron emission tomography or computed tomography on completion of the 2nd cycle. †Final response was assessed at the end of planned treatment (4th cycle) and whenever disease progression was suspected.

Fig. 1.

Response to pralatrexate and bortezomib in patient with angioimmunoblatic T-cell lymphoma (Case 4). PET-CT scan images documenting disease before (A) and after 4 cycles of combination treatment (B).

The most common adverse events were mucositis and anorexia (Table 2). Four patients complained of mucositis, but only 1 week delay of treatment was required for grade 3 mucositis in one patient. Most of the patients tolerated combination therapy. All patients were treated with planned pralatrexate without dose reduction or discontinuation due to toxicity. Only one dose of bortezomib was omitted due to peripheral neuropathy among all patients and one episode of herpes zoster occurred. None of the patients postponed treatment due to hematologic adverse events. One patient had grade 3 thrombocytopenia and there were no cases of greater than grade 2 neutropenia. Other toxicities other than those described above were clinically insignificant.

In our study of elderly patients, the pralatrexate dose was reduced in quantity and frequency with consideration of better tolerability and a synergistic effect with bortezomib. A weekly 15 mg/m2 dose of pralatrexate for 3/4 weeks had good activity with acceptable toxicity in another study in relapsed or refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (11). Weekly 1.3 mg/m2 doses of bortezomib were well tolerated in many previous studies. With this combination regimen of reduced dose, the overall response rate was 2 of 5 (1 PTCL-NOS, 1 AITL). In the PROPEL trial, the largest study ever performed on pralatrexate for relapsed or refractory PTCL, patients were treated with 30 mg/m2 of pralatrexate for 6/7 weeks. Thirty-six percent of patients were more than 65 years. Subgroup analysis revealed that the overall response rate was 33% in elderly patients (5). PTCL subtypes in elderly patients were not specified. Two responders in our study attained first responses after 2 cycles, which is about 8 weeks after treatment. Durations of response were 12 months (ongoing) and 47 days. In the PROPEL study, median time to first and best response was 46 and 141 days respectively. Median duration of response was 10.1 months (5). Overall, efficacy of lower dose pralatrexate combined with bortezomib seems to be acceptable compared with that of the PROPEL study. More importantly, this combination regimen had a more favorable toxicity profile. Mucositis is the most common dose-modifying adverse event of pralatrexate use. Twenty-two percent of patients suffered from grade 3 or 4 mucositis and six percent withdrew from treatment in the PROPEL trial. Only 1 week delay in treatment was needed in our study. Though both pralatrexate and bortezomib provoke cytopenias, the low dose combination regimen did not induce prolonged nor profound cytopenias. There was no grade 3 or 4 neutropenia and only one patient had grade 3 thrombocytopenia. By virtue of a good safety profile, more cycles of treatment could be administered to elderly patients with decreased bone marrow function, leading to better survival.

In conclusion, PTCL is a challenging disease with lack of a standard regimen in the relapsed or refractory setting. Moreover, elderly patients are in need of more tolerable and sustainable treatment with minimal adverse events. Combination therapy with pralatrexate and bortezomib could be used safely and effectively as a salvage regimen in elderly patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL.

Ethics statement

The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital (IRB. No. CNUHH-2015-110). Informed consent was exempted by the board.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclosure.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Research conception and design: Yang DH. Data collection: Lee SS, Jung SH, Ahn JS, Kim YK, Cho MS, Jung SY, Lee JJ, Kim HJ, Yang DH. Data analysis and interpretation: Yang DH, Lee SS. Drafting of the manuscript: Lee SS. Revision of the manuscript: Lee SS. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

References

- 1.A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood. 1997;89:3909–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hennessy BT, Hanrahan EO, Daly PA. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: an update. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:341–353. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abouyabis AN, Shenoy PJ, Sinha R, Flowers CR, Lechowicz MJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of front-line anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens for peripheral T-cell lymphoma. ISRN hematol. 2011;2011:623924. doi: 10.5402/2011/623924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coiffier B, Federico M, Caballero D, Dearden C, Morschhauser F, Jäger U, Trümper L, Zucca E, Gomes da Silva M, Pettengell R, et al. Therapeutic options in relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:1080–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Connor OA, Pro B, Pinter-Brown L, Bartlett N, Popplewell L, Coiffier B, Lechowicz MJ, Savage KJ, Shustov AR, Gisselbrecht C, et al. Pralatrexate in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results from the pivotal PROPEL study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1182–1189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.9024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dondi A, Bari A, Pozzi S, Ferri P, Sacchi S. The potential of pralatrexate as a treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23:711–718. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.902050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchi E, Mangone M, Zullo K, O'Connor OA. Pralatrexate pharmacology and clinical development. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6657–6661. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robak T. Bortezomib in the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Future Oncol. 2015;11:2807–2818. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchi E, Paoluzzi L, Scotto L, Seshan VE, Zain JM, Zinzani PL, O'Connor OA. Pralatrexate is synergistic with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in in vitro and in vivo models of T-cell lymphoid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3648–3658. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallamini A, Stelitano C, Calvi R, Bellei M, Mattei D, Vitolo U, Morabito F, Martelli M, Brusamolino E, Iannitto E, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma unspecified (PTCL-U): a new prognostic model from a retrospective multicentric clinical study. Blood. 2004;103:2474–2479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horwitz SM, Kim YH, Foss F, Zain JM, Myskowski PL, Lechowicz MJ, Fisher DC, Shustov AR, Bartlett NL, Delioukina ML, et al. Identification of an active, well-tolerated dose of pralatrexate in patients with relapsed or refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119:4115–4122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-390211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]