Abstract

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners Patient-Powered Research Network (PPRN) seeks to advance and accelerate comparative effectiveness and translational research in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs). Our IBD-focused PCORnet PPRN has been designed to overcome the major obstacles that have limited patient-centered outcomes research in IBD by providing the technical infrastructure, patient governance, and patient-driven functionality needed to: 1) identify, prioritize, and undertake a patient-centered research agenda through sharing person-generated health data; 2) develop and test patient and provider-focused tools that utilize individual patient data to improve health behaviors and inform health care decisions and, ultimately, outcomes; and 3) rapidly disseminate new knowledge to patients, enabling them to improve their health. The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners PPRN has fostered the development of a community of citizen scientists in IBD; created a portal that will recruit, retain, and engage members and encourage partnerships with external scientists; and produced an efficient infrastructure for identifying, screening, and contacting network members for participation in research.

Keywords: patient-centered outcomes research, patient engagement, person-generated health data, patient-reported outcomes, wearables, PGHD

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) that affect approximately 1.4 million individuals in the United States,1 cost over $6 billion annually,2 and cause substantial patient morbidity,3,4 missed work5 and school,6 and diminished quality of life.7,8 Fortunately, rapid discovery of the genetic, immunological, and microbiome-related factors involved in disease pathogenesis has resulted in an increasing number of new treatment options now available to patients. However, translating new treatments into improved patient-centered care and outcomes will require robust comparative effectiveness (and safety) research. Moreover, combining comparative effectiveness research with translational research will ultimately usher an era of “personalized medicine” in which patients, caregivers, and clinicians make collaborative choices based upon patient preferences and strong and individualized evidence regarding disease prognosis, treatment effectiveness and safety, and response to therapy. For this reason, comparative effectiveness research in IBD has been recognized by the Institute of Medicine and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as a top national priority.9

In response to the growing need for comparative effectiveness and translational research in IBD, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA), the nation’s leading IBD patient support, research, and advocacy foundation, launched the CCFA Partners internet-based cohort study in 2011. CCFA Partners was designed to study the effects of treatment, diet, and other lifestyle factors on patient-reported and other disease outcomes, while simultaneously establishing a technological platform and patient base to support a variety of clinical and translational studies. In 2014, with funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), we began to leverage this infrastructure to transform the cohort study into a Patient-Powered Research Network (PPRN), in conjunction with PCORnet, a National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network, which seeks to advance the nation’s capacity to conduct comparative effectiveness research. PCORnet is composed of Clinical Data Research Networks, which are based on electronic health records of large populations receiving health care within integrated/networked delivery systems, and PPRNs built by communities of motivated patients partnering with researchers.10

The CCFA Partners PPRN is built around a novel Internet cohort of ∼14 200 IBD patients and focuses on patient-reported exposures, health behaviors, and outcomes.11 Our team partners with industry leaders: Crohnology (the leading IBD social network), Validic (an innovative cloud-based platform that connects person-generated data from devices, apps, and wearables to third-party platforms), and Patients Know Best (personal health record vendor) to integrate person-generated health data (PGHD) from mobile health applications, wearables, social networks, and personal health records. The overall objectives of the CCFA Partners PPRN are to: 1) enhance network growth, diversity, and retention; 2) build a robust network community, including patient governance structures that allow greater involvement of patients in research; 3) expand the network data system to include electronic health records, data from mobile health applications (apps) and wearables, and biological samples; 4) develop a customized, scalable, and adaptable distributed data network; 5) develop and test patient- and provider-focused tools that utilize individual patient data to improve health behaviors, health care decisions, and, ultimately, outcomes; 6) further engage the scientific community through open collaboration and data sharing; and 7) rapidly disseminate new knowledge back to patients, enabling them to improve their health.

INFORMATICS INFRASTRUCTURE

PPRN Architecture.

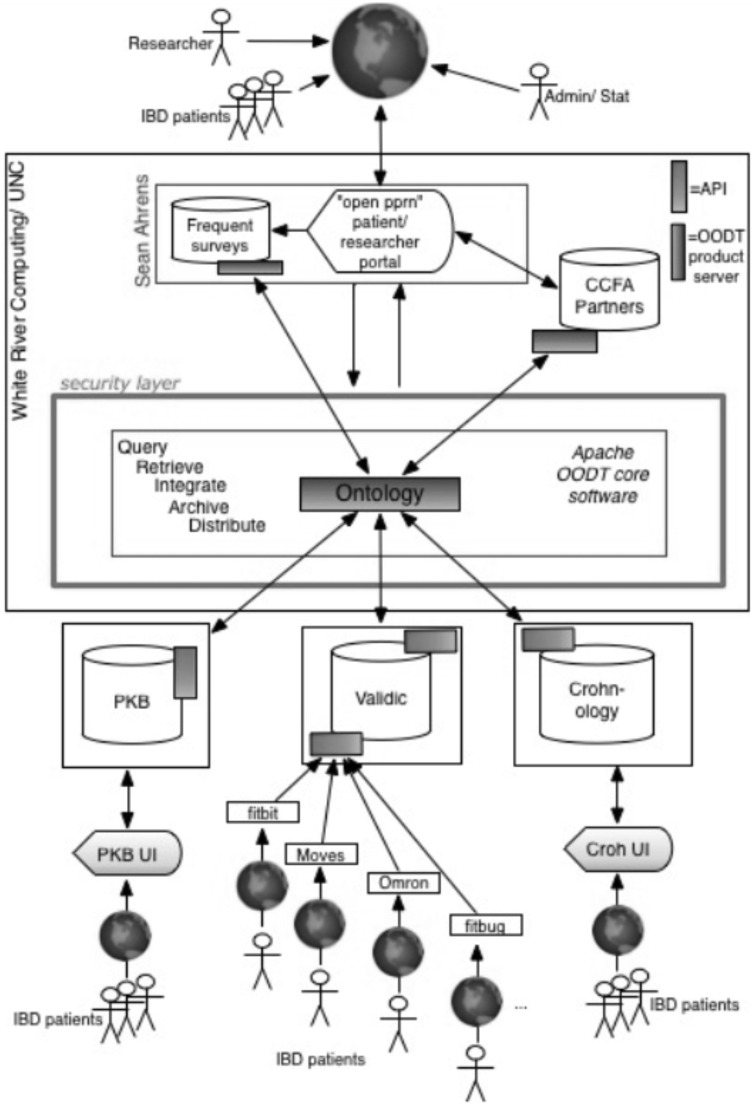

Our PPRN’s informatics architecture utilizes a distributed data model to support the data sharing and integration needs of our PPRN and so that it is scalable, flexible, and adaptable to support future expansion and functionalities (see Figure 1). Our approach centers upon meeting the functional needs of both patient members and the research community, and ensuring that patients have control over their own data, how it is used, and for what purpose. The interactive patient portal is our patient-facing application where patients can complete survey questionnaires; interact with their data and other members; and submit, discuss, and vote on research priorities.

Figure 1:

PPRN Architecture.Apache Object-Oriented Data Technology (OODT) connects distributed, heterogeneous data sources. Data handling and analysis tools use Applied Programming Interfaces to connect the virtual data warehouse and access the PPRN. PKB = Patients Know Best; Croh UI = Crohnology User Interface.

Our PPRN informatics infrastructure leverages open source methods and technology developed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and subsequently delivered to the Apache Software Foundation. Apache Object-Oriented Data Technology (OODT) is the core technology that creates our “virtual” data warehouse, which allows all data to remain stored at its point of capture, unlike a data warehousing approach that moves and consolidates all data centrally. Apache Object-Oriented Data Technology was customized to integrate PPRN data resources: 1) CCFA Partners surveys, which include patient-reported outcomes; 2) wearable and smartphone application data brought in through Validic; 3) Crohnology data; 4) Patients Know Best personal health record data; and 5) frequent short surveys (“check-ins”) administered directly on the PPRN portal. Apache Object-Oriented Data Technology maps and translates data according to our evolving PPRN data model and returns, in real time, an integrated data set to end users (e.g., an individual CCFA Partners member or researcher).

Standardized data elements and vocabularies.

CCFA Partners collects standardized, patient-reported data through core Internet surveys every 6 months. The core surveys consist of questions in the following categories: 1) contact information; 2) demographics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational status, etc.; 3) disease characteristics including disease type and clinical characteristics, family history of IBD, surgical history, hospitalization history, cancer history, etc.; 4) health behaviors including medication use, adherence, smoking, etc.; and 5) disease outcomes, including current disease-related symptoms, quality of life assessments, and other patient reported outcomes (PROs). In addition to these core surveys, CCFA Partners also implements ad-hoc surveys on specific topics as required to support investigator-initiated research studies.

To the extent possible, survey items are based on validated instruments. We deliberately include measures that are both general (National Institutes of Health Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System) and disease-specific (Short CD Activity Index, Short Clinical Colitis Index, and Short IBD Questionnaire). Using the CCFA Partners portal, additional patient-reported data is now collected from smartphones and wearable devices, personal health record data, and short surveys. Our patient governance council members helped guide the selection of measures.

Across all data sources, we are building and expanding a PPRN ontology that uses existing international standards that, ultimately, will include the following components: medications (RXNorm including National Drug Code and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC)), diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases: ICD-9 and ICD-10), procedures (Current Procedural Terminology, ICD-9 Clinical Modification procedure, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System), laboratory data (Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes or LOINC), pathology data (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine or SNOMED), and dietary information (U.S. Department of Agriculture Nutrient Database for Standard Reference). The CCFA Partners PPRN ontology is mapped to the PCORnet Common Data Model where applicable.

PATIENT-CENTERED DESIGN

The design of our network has been informed by qualitative research, including focus groups and one-on-one interviews. To further incorporate the patient voice, we assembled a 5-member Patient Governance Council that has been involved in all aspects of the design process, including prioritization of portal functionalities, drafting the written content of the patient portal, reviewing all survey items, and identifying relevant patient-reported outcomes. Additionally, our lead software developer for the patient portal is a patient with IBD.

CCFA PARTNERS PPRN INTERACTIVE PATIENT PORTAL

Our PPRN’s patient portal seeks to be a “home base” for IBD patients where they can record, contribute, and use their PGHD for self-management and discovery (see Supplemental Figure 1). A brief video for potential members (IBD patients and researchers) that introduces the vision and mission of our PPRN can be viewed on the home page of our portal at www.ccfapartners.org.

During enrollment, patients sign an online informed consent form indicating their willingness to provide PGHD through biannual surveys or directly on our PPRN portal. For each device linked or each additional data stream, there is a separate brief consent by which users can approve the use of this additional data for conducting research. Members can unenroll from the study or opt out of an entire survey or any specific section or question at any time. Similarly, members can disconnect a device/data source at any time. They can also choose to participate in research prioritization functionality or not, and patients can withdraw from study at any time. When a member withdraws, we retain their data but do not initiate any further contact for follow-up, and this is disclosed to members during the consent process.

Members can interface with our PPRN portal using any number of devices and platforms (desktop or mobile, iOS, Android, etc.) such that it can be viewed using the platform/device most convenient to them. Members are able to create a social profile and choose whether it will be shared or private, and whether they want to engage in a community of IBD patients.

Our PPRN collects standardized PROs data at enrollment and then every 6 months, collects short assessments to “check in” about how they are feeling that day, and asks 3 additional symptom questions about the previous 7 days. Members can also enter and update their current medications.

Additionally, patients can connect popular smartphone applications like Moves and wearables like Fitbit to their portal accounts. Members sync their applications and wearable devices using Bluetooth technology to the respective application/device’s platforms (i.e., a Fitbit Zip would sync to the Fitbit app) and Validic’s API allows us to bring the data into the PPRN portal. Our goal is to capture observations of daily living through these mobile health apps and wearables so that patients can continuously add their own experiences and knowledge to enrich our database of PGHD.

The portal is also a medium through which the research team can communicate new research discoveries. Members can see in real time who used their data, for what purpose, and the results of their data contributions.

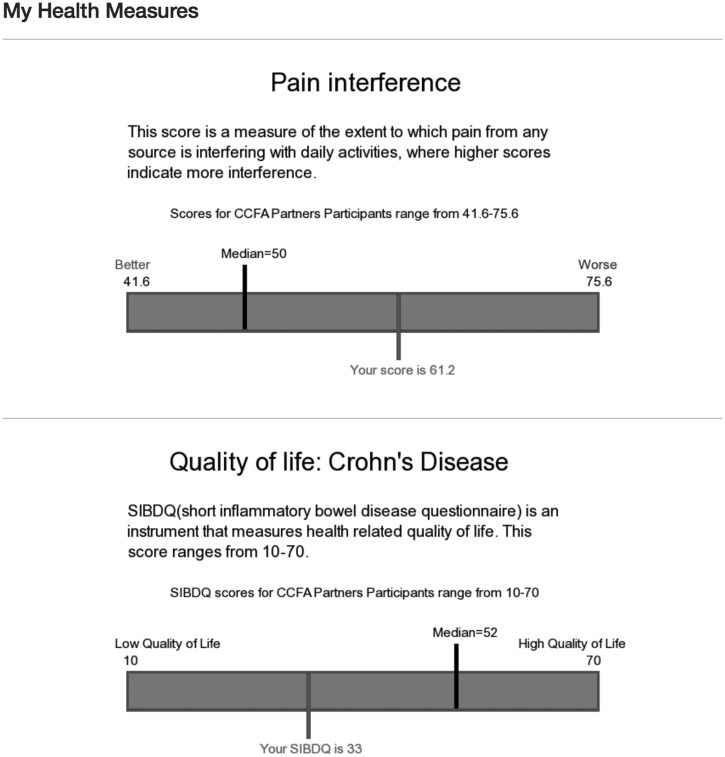

In the My Health Data section of our patient portal, patients can view a series of reports (My Trends, My Measures, and My Dashboard) that integrates multiple types of PGHD (surveys/PROs, mobile health apps, and wearables) to provide summaries of their data that can be used to better understand and monitor trends and gain insights that may help them to manage their symptoms and health, and to facilitate comparisons to aggregate member data across the network and to norms established from aggregate data. For example, a patient may see whether walking more steps/day has improved their disease activity scores over time. Users can also view My Measures, which displays their PROs data such as fatigue or disease activity in relation to established norms among IBD patients (see Figure 2). They can also see a snapshot of key data such as physical activity, sleep, and disease activity in their My Dashboard (see Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Screenshot of My Measures section. This shows an example of data displays of PRO data on pain interference and quality of life.

CROWDSOURCING FOR RESEARCH PRIORITIZATION

Our PPRN is grounded in the philosophy that the most important patient-centered research topics will come from patients living with IBD. Our mission is to cultivate a community of “citizen scientists” who not only envision impactful research questions, but also accelerate IBD comparative effectiveness research through their PGHD contributions. Our members propose their own research ideas, can discuss these ideas and the research issues that are most important to them, and can vote on research topics proposed by peers so that prioritization is crowd-sourced from our members (see Supplemental Figure 3). The research team, which includes patients, then reviews high-priority topics and disseminates these to the broad IBD research community.

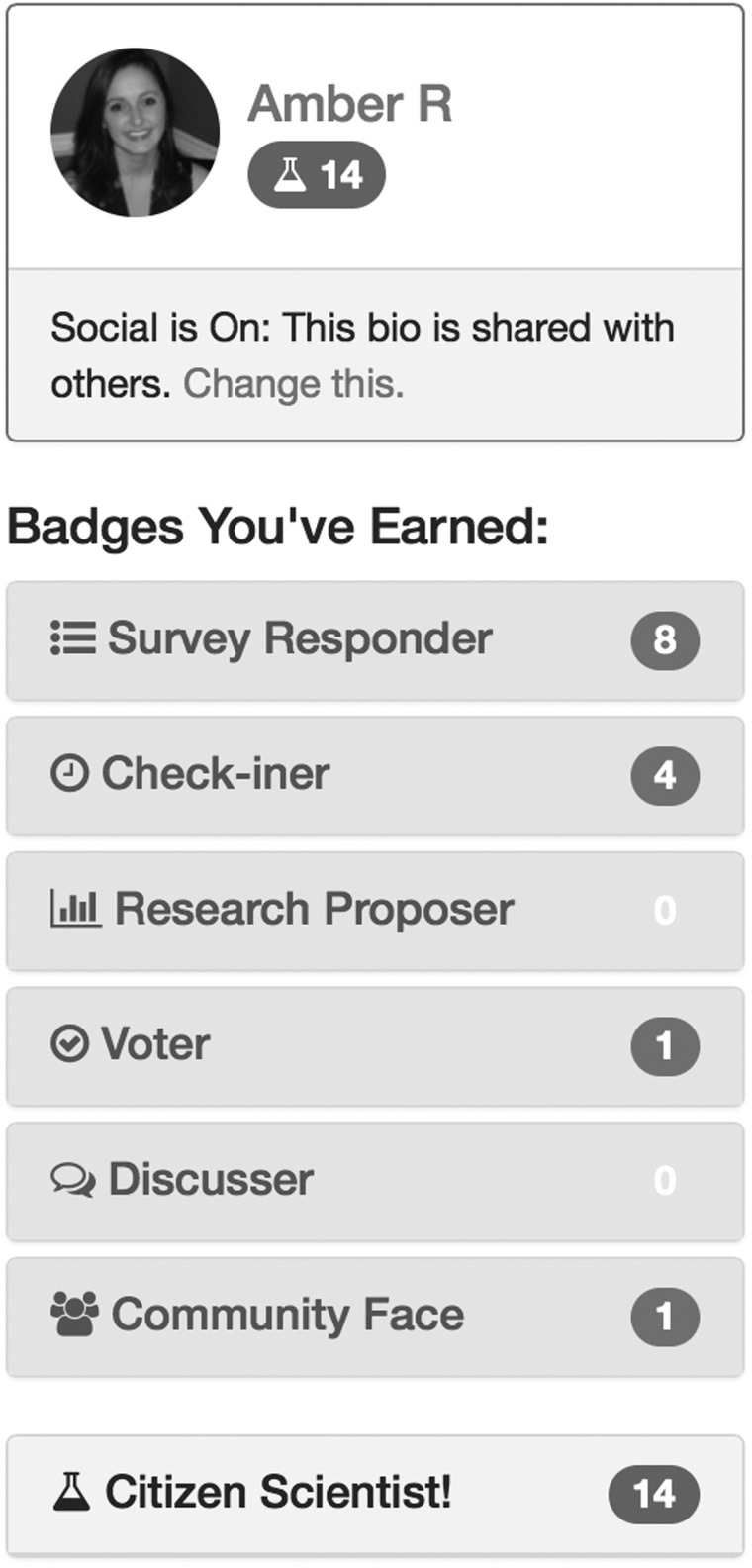

We also designed a virtual badge-based rewards system to foster engagement and excitement around contributing PGHD to the PPRN’s research efforts. Members earn “Citizen Scientist” points for completing daily/weekly survey questionnaires and bi-annual questionnaires, for connecting their smartphone applications and wearables, and for submitting and voting on research topics (see Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Screenshot of the Badges Earned Section.This shows an individual CCFA Partners PPRN member’s contributions to Research (Survey Responder, Check-iner, Voter, Discusser, Community Face, Citizen Scientist.) Amber R. is a part of our research team and this does not show actual patient data.

RECRUITMENT AND ENROLLMENT

Thus far, our PPRN has enrolled ∼14 200 members (∼1% of the US IBD population) from all 50 United States. To date, much of the network growth (∼10 000 members) has been attributed to CCFA email campaigns. We have also employed a grass-roots approach to further increase enrollment and have engaged 40 local CCFA chapters to promote the PPRN during their educational and fundraising events. Indeed, an important lesson learned from this work is the importance of partnering with one or more national advocacy groups. To stimulate network enrollment, we launched a multimedia campaign in connection with the launch of our interactive patient portal in February 2015 (press release, promotional videos, email campaigns, IBD blogger publicity, and social media). Our future growth plans include cross-fertilization with other multicenter cohort studies in which participants will be invited to join our PPRN.

NETWORK MEMBERSHIP AND ENGAGEMENT

Members are mostly between the ages of 18–64 years old with a mean age of 43 years, female, white, and educated (see Table 1). The racial and ethnic demographics of IBD in the United States are largely unknown, and therefore it is not possible to fully assess the representativeness of the CCFA Partners membership. Within the limited data that is available, data suggests that the racial and ethnic composition of patients with IBD is somewhat different than the general US population. Compared to the white population, IBD affects a lower proportion of Blacks (Odds Ratio 0.4), Hispanics (Odds Ratio 0.2), and Asians (Odds Ratio 0.3).12 Nevertheless, because our cohort does not include patients without Internet access or with low levels of education/literacy, our membership may slightly underrepresent minority populations with IBD. Given the importance of increasing diversity, our PPRN will be focusing on minority recruitment, and we have recently conducted a focus group to better inform these efforts.

Table 1:

CCFA Partners Network demographics

| N = 14 062 | Percentage of members |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 18–44 | 50.6 |

| 45–64 | 37.5 |

| 65 and older | 11.7 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 71.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 86.8 |

| Black or African American | 2.2 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.3 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.2 |

| Other/unknown (multirace) | 9.6 |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity | 3.3 |

| Education | |

| < 12th grade | 1 |

| High school | 31 |

| College or advanced degree | 68 |

Long-term follow up is an essential component of all cohort studies and particularly in studies of chronic conditions, such as IBD. CCFA Partners collects longitudinal follow-up data through biannual surveys, along with other recently-added methods of obtaining PGHD as described above. Nearly all members (89%) have completed baseline surveys. Sixty-four percent of members who have been enrolled for 6 months or longer have completed 1 or more follow-up surveys. Over 2300 members have contributed patient reported data for > 3.5 years. The total follow-up time in our PPRN is over 21 300 person-years (mean length of follow up is 1.5 years). Supplemental Figure 4 provides a graphical illustration of the distribution of follow-up time in our PPRN. From July to December 2014, the response rate to follow-up surveys sent to active members was 76%. Patients have contributed 14 862 509 data elements across 36 content areas from 47 174 surveys, and all have signed consent indicating their willingness to be contacted for future research studies.

Our PPRN members have proposed 67 research questions and there are currently 12 research ideas being studied. Eight hundred and seventeen votes have been cast for proposed research ideas with the most votes (123) cast thus far for: “We should compare individuals who manage their disease with medication and those who manage their disease with popular diets within the IBD community.”

PARTNERSHIPS, COLLABORATIONS, AND RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY

Our PPRN has an open and transparent process for collaborating with external researchers. Our “For Researchers” website contains: 1) a summary of past, current, and proposed studies; 2) a data dictionary; 3) instructions and timelines for submitting study proposals; and 4) an overview of the cost structure. All study submissions are reviewed by patients and scientists. To date, we have received 37 research study proposals from outside investigators and 20 have been approved by our PPRN Project Selection Committee.

Our network also has a proven track record for undertaking epidemiological, translational, and interventional research, having already produced 11 peer-reviewed scientific papers11,13–20 and 25 abstracts, with several additional studies underway. Representative examples of ongoing or completed PPRN research includes: 1) a cross-sectional and longitudinal validation of Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System measures in IBD16, 2) several longitudinal studies evaluating the impact of lifestyle factors on IBD disease course21,22, 3) a feasibility study to establish best practices and evaluate response rates for bio-banking among PPRN members, 4) a PCORI-funded study to evaluate patient preferences for competing treatment options among IBD patients, and 5) targeted recruitment for independent clinical and translational studies.

Although the CCFA Partners PPRN has been developed to facilitate epidemiological, clinical, and translational research in IBD, this model is broadly applicable to research in other chronic conditions. Indeed, Phase I of PCORnet consisted of 17 other PPRNs with whom our network has collaborated and shared best practices and lessons learned over the past 18 months. We anticipate that, in the future, collaboration and resource sharing across PPRNs will accelerate the efficiency and pace of network development. As the PPRN matures, facilitating and sustaining engagement with the portal will be critical. Continuous feedback from our membership will allow us to solicit and gauge which features and functionalities are the most useful to patients. Additionally, we must ensure that our members’ data and privacy are safeguarded appropriately and that any potential conflicts of interest are disclosed transparently. Patient input during the formative stages of the PPRN were vital to shaping our engagement and governance strategies, and we believe that the continued involvement from our members will be important to help our PPRN be flexible in meeting members’ needs.

CONCLUSION

Our CCFA Partners PPRN engages patients and researchers to collaboratively advance comparative effectiveness research through enriching existing research datasets with PGHD. Future steps include further collaborations with PCORnet Clinical Data Research Networks and enhancing user-centered interactive data displays to help patients harness PGHD and transform their PGHD into knowledge and insights that help them manage their IBD, symptoms, and overall health. We believe that leveraging technologies to create a community of engaged patients and facilitate the collection and sharing of PGHD is a model that may be broadly applicable to many chronic conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge and thank all the CCFA Partners PPRN collaborative organizations. We thank and acknowledge additional members of the CCFA Partners Patient Governing Committee: Nicholas Uzl, Susan Johnson, Andrew Garb, and Brian Price. We also acknowledge our industry stakeholder, Dr. Suzanne Cook. We also thank and acknowledge Brent Fagg and Ryan Beckland from Validic and Emily Zhao and Dr. Mohammad Al-Ubaydli from Patients Know Best. We also thank and acknowledge our partner organizations: Crohnology, Validic, and Patients Know Best.

CONTRIBUTORS

A.C. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors provided input in the creation of the CCFA Partners PPRN portal and all authors helped to critically review and revise the manuscript and approved the final version.

FUNDING

This research was supported, in part, by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, the National Institutes of Health (P30 DK034987), PCORI and GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Chung reports receiving funding support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and National Institutes of Health, through Grant 1KL2TR001109. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

COMPETING INTERESTS

Dr. Kappelman reports that he is a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline. Mr. Ahrens is the founder and CEO of Crohnology; Ms. Anton is one of the founders of White River Computing; Mr. Myers is the founder and CEO of Atomo, Inc.; and each of them had paid roles in the development of the CCFA Partners Patient Powered Research Network Portal. All other authors do not have any competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available online at http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, Cook SF. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(2):519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(6):1907–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernier-Massouille G, Balde M, Salleron J, et al. Natural history of pediatric Crohn’s disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(4):1106–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE, et al. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(4):1114–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longobardi T, Jacobs P, Bernstein CN. Work losses related to inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(5):1064–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferguson A, Sedgwick DM, Drummond J. Morbidity of juvenile onset inflammatory bowel disease: effects on education and employment in early adult life. Gut. 1994;35(5):665–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen RD. The quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(9):1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akobeng AK, Suresh-Babu MV, Firth D, Miller V, Mir P, Thomas AG. Quality of life in children with Crohn’s disease: a pilot study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28(4):S37–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eden J, Wolman D, Greenfield S, Sox H. Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleurence RL, Curtis LH, Califf RM, Platt R, Selby JV, Brown JS. Launching PCORnet, a national patient-centered clinical research network. JAMIA. 2014;21(4):578–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long MD, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, et al. Development of an internet-based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (CCFA Partners): methodology and initial results. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(11):2099–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YR, Loftus EV, Jr, Cangemi JR, Picco MF. Racial/Ethnic and regional differences in the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Digestion. 2013;88(1):20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ananthakrishnan AN, Long MD, Martin CF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Sleep disturbance and risk of active disease in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(8):965–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen AB, Lee D, Long MD, et al. Dietary patterns and self-reported associations of diet with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. Digestive Dis Sci. 2013;58(5):1322–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herfarth HH, Martin CF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD, Long MD. Prevalence of a gluten-free diet and improvement of clinical symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(7):1194–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kappelman MD, Long MD, Martin C, et al. Evaluation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(8):1315–1323 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long MD, Cadigan RJ, Cook SF, et al. Perceptions of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases on biobanking. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1):132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randell RL, Long MD, Cook SF, et al. Validation of an internet-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease (CCFA partners). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(3):541–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Randell RL, Long MD, Martin CF, et al. Patient perception of chronic illness care in a large inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(7):1428–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasan SK, Calderwood AH, Long MD, Kappelman MD, Sandler RS, Farraye FA. Immunization rates and vaccine beliefs among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: an opportunity for improvement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(2):246–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ananthakrishnan AN, Long MD, Martin CF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Sleep disturbance and risk of active disease in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(8):965–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones PD, Kappelman M, Martin CF, Chen W, Sandler RS, Long MD. Mo1351 association between exercise and future flares in an inflammatory bowel disease population in remission. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):S644. [Google Scholar]